Abstract

Ekbom disease (EKD), formerly known as restless legs syndrome (RLS) has affected and bothered many people over the centuries. It is one of the most prevalent neurological disorders in Europe and North-America, affecting about 10% of the population. The main characteristics are the strong urge to move, accompanied or caused by uncomfortable, sometimes even distressing, paresthesia of the legs, described as a “creeping, tugging, pulling” feeling. The symptoms often become worse as the day progresses, leading to sleep disturbances or sleep deprivation, which leads to decreased alertness and daytime functions. Numerous studies have been conducted assessing the efficacy of dopaminergic drugs, opioids, and other pharmacologic agents in alleviating EKD symptoms. However, there is also a growing body of evidence demonstrating the effectiveness of nonpharmacologic treatments including life style changes, physical activity programs, pneumatic compression, massage, near-infrared light therapy, and complementary therapies. The working mechanisms behind these alternatives are diverse. Some increase blood flow to the legs, therefore reducing tissue hypoxia; some introduce an afferent counter stimulus to the cortex and with that “close the gate” for aberrant nerve stimulations; some increase dopamine and nitric oxide and therefore augment bio-available neurotransmitters; and some generate endorphins producing an analgesic effect. The advantages of these treatments compared with pharmacologic agents include less or no side effects, no danger of augmentation, and less cost.

Introduction

Restless legs syndrome (RLS) has affected and bothered many people over the centuries.Citation1 In 1685, patients with RLS were first described as suffering as if going through torture.Citation2 It took another 260 years before the first detailed description of the medical traits of RLS was published.Citation2 Shortly thereafter, in 1960, Ekbom defined all clinical features and coined the term restless legs syndrome.Citation1 In his honor, the name of this pathology was recently changed to Ekbom disease (EKD). EKD is one of the most prevalent neurological disorders in Europe and North-America, affecting about 10% of the population, with women being afflicted almost twice as often as men.Citation3,Citation4 The usual presentation of this condition is characterized by a strong urge to move, accompanied or caused by uncomfortable, or even distressing paresthesia of the legs, described as a “creeping, tugging, pulling” feeling.Citation1 The symptoms often become worse as the day progresses, leading to sleep disturbances or sleep deprivation, which further result in impairment of alertness and daytime functions.Citation5

Ekbom disease is generally classified as “primary” (genetic or idiopathic) or “secondary” (related to other medial or neurological disorders) or it can arise from a combination of factors.Citation6 The treatment for secondary EKD is aimed mostly at dealing with the underlying conditions. For example, low serum iron levels are associated with EKD,Citation1,Citation7–Citation9 and it has been shown that administration of iron can decrease EKD symptoms.Citation10 Other pathologies such as diabetes mellitus, end stage renal disease, vitamin B12 deficiency, folate deficiency,Citation9 Parkinson’s disease,Citation11 uremia, and fibromyalgiaCitation12 have been associated with EKD. The options discussed in this paper will be most beneficial for the treatment of primary EKD.

The diagnosis is based primarily on the complaints of the patient, as there are no biomarkers, classic measurable clinical findings, conclusive blood assays, or radiological and sleep studies that can clearly implicate EKD. A long-needed, standardized way to identify and substantiate EKD was developed by the International Restless Legs Syndrome Study Group (IRLSSG).Citation13 It is a four-question survey that explores 1) whether the subjects have an urge to move their legs, 2) whether the symptoms begin or worsen during periods of inactivity, 3) whether the urge to move is at least partially relieved by movement, and 4) whether this urge to move is worse in the evening or night.Citation13 Affirmative answers to all four questions means that the criteria for EKD diagnosis are met. The IRLSSG also defined three supportive features; they are: family history, presence of periodic limb movement, and the response to dopaminergic treatment.Citation13 While they are not essential to the diagnosis of EKD, their presence can help resolve diagnostic ambiguity.

Diagnosis and evaluation of EKD

Different tools are available that measure severity of the symptoms and their impact on a person’s life and track a person’s progress or decline: the IRLSSG rating scale, Johns Hopkins RLS severity scale, RLS quality of life instrument, Epworth sleepiness scale, and the fatigue visual analog scale.Citation14 The IRLSSG rating scaleCitation15 is a 10-question scale, developed by the IRLSSG as a means of assessing the severity of EKD and of tracking changes in symptoms associated with this pathology.Citation15 It assesses the impact of EKD in a patient’s quality of life and function. Each question can be answered with one of five possible answers with attached points (0–4) according to severity. Therefore, a maximal score of 40 can be obtained. Generally, an IRLSSG rating scale score between 1 and 10 corresponds to “mild”, 11–20 “moderate”, 21–30 “severe”, and 31–40 “very severe” EKD. The Johns Hopkins RLS severity scale was the first published clinical scale to assess EKD severity.Citation16 It consists of only one item, which asks for the time of day the symptoms start. Four possible answers are linked to scores as follows: 0 = no symptoms, 1 = bedtime-only symptoms (after or within an hour of going to bed), 2 = evening and bedtime symptoms (starting at or after 6 pm), and 3 = day and night symptoms (starting before 6 pm). This scale was mostly created for screening and epidemiological research.Citation16 The RLS quality of life instrumentCitation17 consists of 17 questions assessing domains such as daily function, social function, sleep quality, and emotional wellbeing. For each question, the possible answers range from “never” to “very often”, with an attached score ranging from 5 to 1 respectively. The scores for the different domains are calculated separately. The Epworth sleepiness scaleCitation18 is used to determine the level of daytime sleepiness by giving the patient eight situations and asking for the chance of dozing off or falling asleep during those scenarios. The four possible answers are each linked to 0–3 points respectively. A score of 10 or more is considered “sleepy”, a score of 18 or more is considered “very sleepy”. The fatigue visual analog scale is a unidimensional fatigue measurement. Here the patient has to mark his/her level of experienced fatigue (during a determined time frame) on a 10-cm line. Its anchors are “no fatigue” on one side and “worst possible fatigue” on the other.

Pathogenesis

Compounding the fact that EKD has no measurable signs is the uncertainty about its patho-genesis. In the 1940s and 1950s it was assumed that EKD stemmed from vascular disturbances.Citation2 This theory came under disfavor when it was observed that patients with EKD responded well to dopaminergic agents, such as Levodopa, and dopamine agonists. Levodopa, a precursor of dopamine that can cross the blood–brain barrier and is metabolized in the brain into dopamine, is also used to treat Parkinson’s disease, a low dopamine condition. It is this similar treatment response between Parkinson’s disease and EKD that resulted in speculations that these two disorders might be related in their origins.Citation19 Different hypotheses on EKD etiology – or lack thereof – prompt different treatment suggestions: the ones trying to manage the symptoms by changing the lifestyle, the ones tackling the peripheral nervous system and blood flow, and the ones addressing dopamine regulation in the central nervous system via pharmaceuticals.

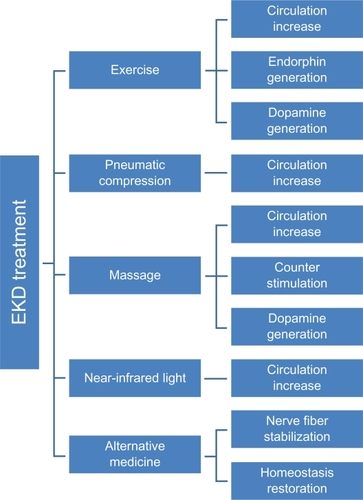

Hundreds of articles exist on the treatment of EKD with pharmaceuticals. Many authors recommend exercises or other adjunct modalities for the treatment of EKD,Citation6,Citation12,Citation20–Citation27 but there are not many studies assessing the efficacy of other treatments. I found: one systematic review assessing efficacy of acupuncture in the treatment of EKD;Citation28 three randomized controlled trials (RCTs) (one assessing a 12-week exercise program,Citation29 one assessing a pneumatic compression device worn daily,Citation14 and one evaluating the efficacy of near-infrared [NIR] light treatmentCitation30); three prospective interventional studies evaluating the efficacy of physical exercise,Citation31 pneumatic compression device,Citation32 and NIR light;Citation33 and three case reports assessing the effectiveness of massage therapy,Citation34 pneumatic compression device,Citation35 and NIR light.Citation36 All of these studies concluded that EKD symptoms significantly decreased after using these interventions. This article will focus on treatment options involving nonpharmacological alternatives (). For most relevant research see .

Figure 1 EKD treatment options and their potential working mechanisms.

Table 1 Most relevant research

Treatment options

Lifestyle

Lifestyle changes as an intervention for EKD include improving sleep quality by controlling sleep times and by reducing caffeine and alcohol consumption.Citation6,Citation7,Citation29,Citation37 Mental activity, such as reading, card games, or computer work, has been suggested to be successful in decreasing EKD symptoms.Citation38 The success of these choices is not well documented.

Physical activity

Epidemiologic evidence indicates that lack of exercise is a strong predictor of and a significant risk factor for EKD.Citation39 Physical activity and exercise have long been the only nonpharmacological treatment options available to EKD sufferers. In fact, by definition, EKD is the urge to move that is at least partially relieved by movement.Citation13 It was recently shown in a RCT that a 3-day per week exercise program of aerobic and lower-body resistance training significantly decreased EKD symptom severity.Citation29 While the authors did not attempt to explain the reasons for why or how exercise was successful in decreasing EKD severity, one can surmise that the increase in blood flow brought on by activityCitation40 could play a role. Shear forces between the inner wall of the endothelium and the moving blood stimulate the enzyme nitric oxide (NO) synthase.Citation41,Citation42 Once generated, NO diffuses into the smooth muscle of the endothelium and then quickly diffuses through the muscle tissue of the blood vessel. There it activates guanylate cyclase, which then activates the second messenger cGMP (cyclic guanosine monophosphate). Several steps follow and culminate in the relaxation of smooth muscles in the blood vessel. This leads to vasodilation and consequently to increased local blood flow.Citation43–Citation45 NO is also scavenged by hemoglobin in the blood.Citation46 Under low pO2 (partial pressure of oxygen) conditions, during physiologic “hypoxia”, the red blood cells release NO to increase blood flow.Citation46 Another possible reason for the success of exercises in the treatment of EKD symptoms could be the exercise-induced release of endorphins.Citation47 Endorphins are endogenous opioid polypeptide compounds, produced by the pituitary gland and hypothalamus that produce analgesia and a sense of well-being.Citation48 Another central change occurring with exercise, and therefore a further potential mechanism with which physical activity can aid in decreasing EKD symptoms, is the increased release of dopamine.Citation49 It has been shown that especially during high-intensity exercise dopaminergic neurotransmission changes.Citation49 A study assessing the incidence of EKD during sleep following acute physical activity in spinal cord injury subjectsCitation47 found a significant reduction in EKD as measured by polysomnographic sleep parameters and decrease of leg movements. The authors reject the hypothesis that dopamine deficiency could be involved in the symptoms felt by spinal cord-injured EKD sufferers because of their spinal cord trauma. Instead, they suggest that the release of endorphins after physical activity may be the cause for the symptom reduction.

Pneumatic compression devices

One of the first modern-day (1940s and 1950s) hypothesis attempting to explain the etiology of EKD symptoms associated it with decreased blood flow.Citation35 Ekbom,Citation1 too, believed that vasodilators given to EKD sufferers would decrease the symptoms. The vascular hypothesis was later neglected but revived in 2005, when increased vascular blood flow with pulsed compression devices was shown to significantly decrease EKD symptoms in six patients.Citation35 Other studies have followedCitation14,Citation32 confirming these findings. The pneumatic compression devices were applied to the thigh and leg regions; the parameters used were 40 cm H2O of air pressure intermittently for 1 hour. It is hypothesized that vascular compression stimulates the release of endothelial mediators (ie, NO)Citation50 that then can modulate EKD symptoms. It is also possible that intermittent compression, which enhances venous and lymphatic drainage, could relieve subclinical ischemia.Citation14 These findings are not surprising, taking into account that a high prevalence (36%) of EKD in patients present with chronic venous disorder.Citation51

Massage

Tactile and temperature stimulation, including massage or hot baths, can also be successful in decreasing symptoms associated with EKD.Citation38,Citation52 While many authors mention these modalities as potential treatment options and numerous websites recommend them, there is a paucity of scientific trials confirming their efficacy. However, one case reportCitation34 describes a 3-week massage regimen that decreased EKD symptoms significantly. This massage was given for 45 minutes twice a week using techniques such as Swedish massage (effleurage, petrissage), myofascial release, friction to tendinous attachments, stretches, and direct pressure to hip and lower extremity muscles. The symptoms returned after 2 weeks post treatment.Citation34 The author suggests that the natural release of dopamine following massage could have been responsible for the amelioration of the symptoms. Massage has shown to increase dopamine levels in urine by an average of 28% in different conditions.Citation53 Another speculation on the working mechanism of massage in the treatment of EKD is the counter stimulation it provides to the cerebral cortex. The tactile stimulation could supersede afferent input associated with EKD symptoms or at least partially modulate the perception of discomfort in the legs.Citation54 Another explanation involving the central nervous system is the possibility that tactile and temperature stimulations traveling in the spinothalamic tract may modulate neural activity in the thalamus. Bucher et alCitation55 have shown that activation of the thalamus is associated with sensory leg discomfort in idiopathic EKD patients. A fourth explanation could be the mechanically induced increase of circulation. Massage moves venous blood to the heart, transporting nutrients to the tissue and metabolic products away from the tissue. Consequently, the potentially de-oxygenated tissue receives oxygen which then can restore vascular blood gas balance.

NIR light

NIR light has been used in the treatment of neuropathy to increase sensation and decrease pain,Citation56–Citation63 wound healing,Citation64,Citation65 and more recently in the treatment of EKD.Citation30,Citation33,Citation36 The proposed mechanism of NIR light therapy is its ability to generate NO in the endothelium by activating the enzyme nitric oxide synthase (NOS)-3,Citation66 similar to exercise-induced NOS-3 activation. “Intensive illumination”, such as during NIR light treatment, can also free NO from hemoglobin and thus make it bio-available.Citation67 The discomfort that accompanies the EKD-related urge to move could be caused by the lack of tissue oxygen, which would be offset by an increase in blood flow. The urge to move may be a subconsciously driven mechanism to augment blood flow and tissue perfusion. Moving, such as walking or rubbing of legs,Citation40,Citation68 diminishes EKD symptoms as it enhances circulation. Therefore, treatment with a vasodilator, such as NIR-induced NO, could conceivably temporarily decrease the symptoms associated with EKD. Even a prolonged reduction of symptoms (up to a couple of weeks post treatment) has been observed.Citation30 This was explained with a potential systemic effect of light therapy.Citation69 This systemic effect could be responsible for either continued NO production or other changes in the tissue, leading to diminished symptoms. Additionally, NO has influence on neurotransmission.Citation44 It is one of the substances that influences nerve impulse transfer as it assists in converting nerve signals as they cross synapses.Citation44 This quality of NO might also be involved in reducing symptoms associated with EKD. All things considered, NIR could positively impact EKD symptoms by numerous methods.

Complementary and alternative medicine

The use of complementary and alternative medicine is another option available to EKD sufferers. Vitamins rank high on the list.Citation70 Their use in the treatment of EKD symptoms is based on the hypothesis that the unpleasant EKD sensations come from the stimulation of dysfunctional peripheral nerve fibers found along blood vessels.Citation71 Vitamins E and B are associated with the nervous system. Intake of daily 300 mg vitamin E for 1 week may stabilize peripheral blood circulation and decrease symptoms.Citation71 Vitamin B12 intake may support the stability of nerve fibers, preventing excessive sensitivity and add further to the decrease of EKD symptoms.Citation71 Multivitamins and vitamin C intake are also used to decrease EKD symptoms, followed by glucosamine, zinc, folic acid, vitamin D, and magnesium.Citation70 Nonbiologically based treatment options include prayer, meditation, and music.Citation70 Acupuncture is also considered an alternative medicine. It is an ancient Chinese medical therapy used in the prevention and treatment of disease.Citation28 It involves inserting needles into specific points on the body. A review articleCitation28 studied several kinds of acupuncture methods, such as body acupuncture, auricular acupuncture, scalp acupuncture, electro-acupuncture, laser acupuncture, acupressure, and acupoint injection therapy for the treatment of EKD symptoms. The authors concluded that the evidence that acupuncture is an effective treatment option for EKD sufferers is still insufficient to support the hypothesis that acupuncture is more effective than no treatment or other therapies.

Placebo

As with all medication and treatment, the power of placebo must not be underestimated. The Latin word “placebo” means: “I shall please”, indicating a certain conscious expectation from a treatment. This means, that the context and environment of the treatment plays an important role in the patient’s improvement potential.Citation72 A recent meta-analysisCitation73 assessing the placebo effect in EKD treatment studies found a considerable placebo response associated with EKD treatment. On average, more than one-third of EKD subjects experience a major improvement of EKD symptoms while receiving placebo treatment. The authors propose that the reason for this might be related to EKD’s unique responsiveness to dopaminergic agents and opioids – both systems implicated in the placebo response.

Conclusion

This article focused on treatment options for mainly primary EKD, involving nonpharmacological alternatives. Recommendations for patients with EKD suggest that certain life style changes, exercise, treatment modalities, as well as alternative medicine are linked to a decrease of symptoms associated with EKD. There is no research assessing the possibility of an enhanced effect of these modalities when applied together. It is very likely that the pathogenesis of this condition is multifaceted and therefore demands a comprehensive treatment approach. Because of the possible myriad side effects when treating EKD with pharmaceuticals, the treatment options named above should be given consideration.

Disclosure

The author declares no conflict of interest.

References

- EkbomKRestless legs syndromeNeurology19601086887313726241

- CoccagnaGVetrugnoRLombardiCProviniFRestless legs syndrome: an historical noteSleep Med2004527928315165536

- BenesHWas gibt es Neues zum Restless-legs-Syndrom?Psychoneuro2004308438443

- BergerKLuedemannJTrenkwalderCJohnUKesslerCSex and the risk of restless legs syndrome in the general populationArch Intern Med200416419620214744844

- KushidaCAllenRAtkinsonMModeling the causal relationship between symptoms associated with restless legs syndrome and the patient-reported impact of RLSSleep Med2004548548815341894

- OertelWTrenkwalderCZucconiMState of the art in restless legs syndrome therapy: practice recommendations for treating restless legs syndromeMov Disord200722S466S47517516455

- ThorpyMNew paradigms in the treatment of restless legs syndromeNeurology200564Suppl 3S28S3315994221

- SunEChenCHoGEarlyCAllenRIron and the restless legs syndromeSleep19982143713779646381

- LeeKZaffkeMBaratte-BeebeKRestless legs syndrome and sleep disturbance during pregnancy: the role of folate and ironJ Wom Health Gend Base Med2001104335341

- EarleyCJHecklerDAllenRPThe treatment of restless legs syndrome with intravenous iron dextranSleep Med20045323123515165528

- Appiah-KubiLSPalSChaudhuriKRRestless legs syndrome (RLS), Parkinson’s disease, and sustained dopaminergic therapy for RLSSleep Med.20023Suppl 1S51S5514592168

- GlasauerFRestless legs syndromeSpinal Cord20013912513311326321

- AllenRPicchiettiDHeningWTrenkwalderCWaltersAMontplaisiJRestless legs syndrome: diagnostic criteria, special considerations, and epidemiology A report from the restless legs syndrome diagnosis and epidemiology workshop at the National Institutes of HealthSleep Med2003410111914592341

- LettieriCEliassonAPneumatic compression devices are an effective therapy for restless legs syndrome: a prospective, randomized, double-blinded, sham-controlled trialChest2008135748019017878

- The International Restless Legs Syndrome Study GroupValidation of the international restless legs syndrome study group rating scale for restless legs syndromeSleep Med2003412113214592342

- KohnenRAllenRBenesHAssessment of restless legs syndrome – methodological approaches for use in practice and clinical trialsMov Disord.200722S18S485S49417534967

- AtkinsonMAllenRDuChaneJValidation of the restless legs syndrome quality of life instrument (RLS-QLI): findings of a consortium of national experts and the RLS FoundationQual Life Res20041367969315130030

- JohnsMA new method for measuring daytime sleepiness: the Epworth sleepiness scaleSleep1991145405451798888

- OndoWVuongKJankovicJExploring the relationship between Parkinson disease and restless legs syndromeArch Neurol20025942142411890847

- HeningWCurrent guidelines and standards of practice for restless legs syndromeAm J Med.20071201AS22S2717198767

- [Anon]Restless leg syndromeHarv Mens Health Watch200712256

- LakasingEExercise beneficial for restless legs syndromePractitioner20082521706434518575387

- TrenkwalderCKönnen Entspannungsübungen die Beine beruhigen?MMW Fortschr Med200614827–281616888852

- Von AlbertHDie Behandlung von Restless legsFortschr Med1990108240442312024

- [Anon]Exercise eases nighttime leg twitchesHarv Women’s Health Watch20091697

- MurtaghJMusculoskeletal medicine tip. Restless leg syndromeAust Fam Physician19901957562346431

- SilberMEhrenbergBAllenRAn algorithm for the management of restless legs syndromeMayo Clin Proc20047991692215244390

- CuiYWangYLiuZAcupuncture for restless legs syndrome (review)Cochrane Database Syst Rev20081084CD00645718843716

- AukermanMAukermanDBayardMTudiverFThorpLBaileyBExercise and restless legs syndrome: a randomized controlled trialJ Am Board Fam Med20061948749316951298

- MitchellUMyrerJJohnsonAHiltonSRestless legs syndrome and near-infrared light: an alternative treatment optionPhysiother Theory Pract. Epub 2010 Oct 26.

- De MelloMEstevesATufikSComparison between dopaminergic agents and physical exercise as treatment for periodic limb movements in patients with spinal cord injurySpinal Cord20044221822115060518

- EliassonALettieriCSequential compression devices for treatment of restless legs syndromeMedicine200786631732318004176

- MitchellUJohnsonAMyrerJComparison of two infrared devices in their effectiveness in reducing symptoms associated with RLSPhysiother Theory Pract. Epub 2010 Oct 16.

- RussellMMassage therapy and restless legs syndromeJ Bodywork Movement Ther2007112146150

- RajaramSShanahanJAshCWaltersAWeisfogelGEnhanced external counter pulsation (EECP) as a novel treatment for restless legs syndrome (RLS): a preliminary test of the vascular neurologic hypothesis for RLSSleep Med2005610110615716213

- MitchellUUse of near-infrared light to reduce symptoms associated with restless legs syndrome: a case reportJ Med Case Rep20104286

- Ferini-StrambiLAarskogDPartinenMEffect of pramipexole on RLS symptoms and sleep: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trialSleep Med20089887488118952497

- GamaldoCEarleyCRestless legs syndromeChest20061301596160417099042

- PhillipsBYoungTFinnLAsherKHeningWPurvisCEpidemiology of restless legs symptoms in adultsArch Intern Med20001602137214110904456

- CliffordPHellstenYVasodilatory mechanisms in contracting skeletal muscleJ Appl Physiol20049739340315220322

- BurkeT5 questions – and answers – about MIRE treatmentAdv Skin Wound Care200316736937114688646

- BugaGGoldMFukutoJIngarroLShear stress-induced release of nitric oxide from endothelial cells grown on beadsHypertension1991171871931991651

- IgnarroLBugaGWoodKByrnsREndothelium-derived relaxing factor produced and released from artery and vein is nitric oxideProc Natl Acad Sci U S A198784926592692827174

- MoncadaSPalmerRHiggsENitric oxide: physiology, pathophysiology, and pharmacologyPharmacol Rev19914321091421852778

- BallermannBDardikAEngELiuAShear stress and the endotheliumKidney Int.198954S67S100S108

- AzarovIHuangKTBasuSGladwinMTHoggNKim-ShapiroDBNitric oxide scavenging by red blood cells as a function of hematocrit and oxygenationJ Biol Chem200528047390243903216186121

- De MelloMLauroFSilvaATufikSIncidence of periodic leg movement and of the restless legs syndrome during sleep following acute physical activity in spinal cord injury subjectsSpinal Cord1996342942968963978

- KoneruASatyanarayanaSRizwanSEndogenous opioids: their physiological role and receptorsGlobal J Pharmacol200933149153

- PetzingerGFisherBVan LeeuwenJ-EEnhancing neuroplasticity in the basal ganglia: the role of exercise in Parkinson’s diseaseMov Disord.201025S1S141S14520187247

- SunDHuangARecchiaFNitric oxide-mediated arteriolar diation after endothelial deformationAm J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol2001280H714H72111158970

- McDonaghBKingTGuptanRRLS in patients with chronic venous disorderPhlebology200722415616318265529

- RyanMSlevinJRestless legs syndromeJ Pharm Pract2007206430448

- FieldTMassage therapy effectsAm Psychol19985312127012819872050

- MelzackRWallPPain mechanisms: a new theoryScience19651509719795320816

- BucherSSeelosKOertelWReiserMTrenkwalderCCerebral generators involved in the pathogenesis of the restless legs syndromeAnn Neurol1997416396459153526

- DeLellisSCarnegieDBurkeTImproved sensitivity in patients with peripheral neuropathy: effects of monochromatic infrared photo energyJ Am Podiatr Med Assoc200595214314715778471

- HarklessLDeLellisSBurkeTImproved foot sensitivity and pain reduction in patients with peripheral neuropathy after treatment with monochromatic infrared photo energy – MIRE™J Diabetes Complications2006202818716504836

- KochmanAMonochromatic infrared photo energy and physical therapy for peripheral neuropathy: influence on sensation, balance and fallsJ Geriatr Phys Ther2004271619

- KochmanACarnegieDBurkeTSymptomatic reversal of peripheral neuropathy in patients with diabetesJ Am Podiatr Med Assoc20029212513011904323

- LeonardDFarooqiMMyersSRestoration of sensation, reduced pain, and improved balance in subjects with diabetic peripheral neuropathy; a randomized, double blind, placebo controlled studyDiabetes Care20042716817214693984

- VolkertWHassanAHassanMEffectiveness of monochromatic infrared photoenergy and physical therapy for peripheral neuropathy: changes in sensation, pain and balance – a preliminary, multi-center studyPhys Occup Ther Geriatr2006242117

- PrendergastJMirandaGSanchezMImprovement of sensory impairment in patients with peripheral neuropathyEndocr Pract200410243015251618

- PowellMCarnegieDBurkeTReversal of diabetic peripheral neuropathy and new wound incidence: the role of MIREAdv Skin Wound Care200417629530015289717

- HorwitzLBurkeTCarnegieDAugmentation of wound healing using monochromatic infrared energyAdv Wound Care199912354010326355

- AndersonRParrishJThe optics of human skinJ Invest Dermatol19817713197252245

- MatsunagaKFurchgottRInteractions of light and sodium nitrite in producing relaxation of rabbit aortaJ Pharmacol Exp Ther19892486876942537410

- VladimirovYBorisenkoaGBoriskinaaNKazarinovbKOsipovaANO–hemoglobin may be a light-sensitive source of nitric oxide both in solution and in red blood cellsJ Photochem Photobiol B2000591–311512211332878

- ThijssenDDawsonEBlackMHopmanMCableNGreenDBrachial artery blood flow response to different modalities of lower limb exerciseBed Sci Sports Exerc200941510721079

- DysonMPrimary, secondary and tertiary effects of photoherapy: a reviewProc SPIE.20066140614005

- CuellarNGalperDTaylorAD’HuyvetterKMiederhoffPStubbsPRestless legs syndromeJ Altern Complement Med200410342242315253844

- SugitaYIs restless legs syndrome an entirely neurological disorder?Eur J Gen Pract200814454618464174

- KoshiEShortCPlacebo theory and its implications for research and clinical practice: a review of the recent literaturePain Practice20077142017305673

- FuldaSWetterTWhere dopamine meets opioids: a meta-analysis of the placebo effect in RLS treatment studiesBrain200813190291717932100