Abstract

Aims:

To perform a systematic literature review of studies in peer reviewed journals on the epidemiology, economics, and treatment patterns of epilepsy in selected countries in emerging markets.

Methods:

A literature search was performed using relevant search terms to identify articles published from 1999 to 2000 on the epidemiology, economics, and treatment patterns of epilepsy. Studies were identified through electronic Embase®, Cochrane©, MEDLINE®, and PubMed® databases. Manual review of bibliographies allowed for the detection of additional articles.

Results:

Our search yielded 65 articles. These articles contained information relevant to epidemiology (n = 16), treatment guidelines (n = 4), treatment patterns (n = 33), unmet needs (n = 4), and economics (n = 8). From a patient perspective, patients with less than or equal to two adverse events (AEs) while taking anti-epileptic drugs (AEDs) had significantly lower annual costs than those having greater than or equal to three AEs, as did patients with fewer seizures. The overall mean annual cost for epilepsy per patient ranged from US$773 in China to US$2646 in Mexico. Prevalence data varied widely and were found for countries including Arab League Members, China, India, and Taiwan. In Turkey, active prevalence rates ranged from 0.08/1000 to 8.5/1000, and in Arab countries, active prevalence ranged from 0.9/1000 in Sudan to 6.5/1000 in Saudi Arabia. Seventeen different AEDs were used in the identified studies. The most common AEDs utilized were phenobarbital (21.7%), valproate (17.5%), and tiagabine (16.4%). In all studies, the use of AEDs resulted in an increase of patients who became seizure free and a reduction in seizure frequency and severity.

Conclusion:

Few studies have examined the prevalence and incidence of epilepsy in emerging markets and study limitations tend to underestimate these rates at all times. More cost-effectiveness, cost-minimization, and cost-benefit analyses must be performed to enhance the data on the economics of epilepsy and its therapy in regions with insufficient resources and those emerging markets which contain the majority of the world’s population. And finally, the study found that generic AEDs are frequently used to successfully treat patients with epilepsy in emerging markets.

Introduction

Epilepsy is recognized as a collection of heterogeneous syndromes characterized by additional conditions that coexist with seizures and impacts over 50 million people worldwide.Citation1 Cognitive, emotional, and behavioral comorbidities are common.

Seizures are typically divided into two main categories: partial (focal) and generalized. Generalized seizures affect both cerebral hemispheres from the onset of the seizure. Seizures produce loss of consciousness, either for long periods of time or temporarily, and are sub-categorized into generalized tonic-clonic, myoclonic, absence, or atonic subtypes.Citation2 Partial seizures affect an area within one cerebral hemisphere of the brain and are the most recurring type of seizure experienced by patients with epilepsy.Citation3 Partial seizures are further subdivided into simple partial seizures, where consciousness is retained; and complex partial seizures, where consciousness is diminished or lost.Citation3

In the treatment of epilepsy, no one anti-epileptic drug (AED) has been shown to be the most effective, and all AEDs have published side effects. AEDs are selected following consideration of side effects, ease of use, cost, and physician knowledge. Patients with newly diagnosed epilepsy who require treatment can be started on standard, first-line AEDs such as carbamazepine, phenytoin, valproic acid, or phenobarbital. Alternatively, newer AEDs introduced in the past decade may be used. These include gabapentin, lamotrigine, oxcarbazepine, or topiramate.Citation4 Between 70% and 80% of individuals are successfully treated with one of the AEDs now available and success rates primarily depend on the etiology of the seizure disorder.Citation4 However, the remaining 20%–30% of patients have either intractable or uncontrolled seizures or suffer significant adverse side effects to medication.Citation4 As with the selection of first-line therapy, choosing the appropriate drug for the treatment of refractory epilepsy must be based on the appreciation of each drug’s characteristics and risks for each individual patient.

An emerging market economy is defined as an economy with low-to-middle per capita income.Citation5 Such countries constitute approximately 80% of the global population, are often rapidly-growing and represent about 20% of the world’s economies.Citation5 Although the term emerging market is loosely defined, countries that fall into this category, range from big to small, and are often considered emerging because of development and reform programs that have been put in place to launch their markets globally.Citation5 Consequently, although China is considered one of the world’s foremost economic leaders, it is grouped into the emerging market category together with much smaller economies with fewer resources, such as Sudan or Bulgaria.

Epilepsy is common in patients admitted to hospitals in emerging markets.Citation6 However, there are reported differences in the epidemiology, economic burden, and outcome of epilepsy in these regions compared to high-income countries; although few data from the former regions exist.Citation6 Applying the International League Against Epilepsy definition of epilepsy is problematic in these areas, as patients often arrive at health facilities without adequate documentation of the seizure duration.Citation7

The goal of treatment for patients with epilepsy is no seizures with little to no side effects. However, due to variabilities in clinical presentation and available resources, treatments are highly individualized and vary widely. The objective of this study is to systematically review the literature on epilepsy to identify incidence and prevalence rates, economic data, unmet needs, and treatment patterns in those emerging markets which contain the majority of the world’s population.

Methods

To ensure an extensive examination of the literature, this study included all published randomized clinical trials and observational peer-reviewed studies that examined factors associated with epilepsy in emerging markets. A comprehensive search of the literature was performed using PubMed, EMBASE, and Cochrane Review databases on the following topics concerning epilepsy in emerging markets: epidemiology, including prevalence and incidence; economics, including burden of disease, effects on productivity, and other economic issues; guidelines for treatment; treatment patterns; drug usage patterns; and unmet needs.

Search strategy and study selection

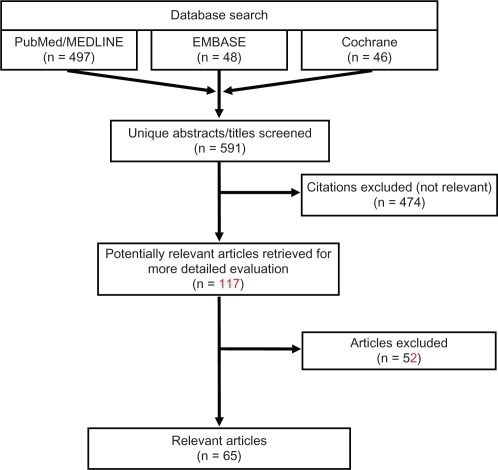

The initial search strategy was developed in the PubMed/MEDLINE database (). A search string was constructed utilizing varied approaches to identify the most comprehensive and effective method for retrieving studies specific to the study objective. Methods were explored using MeSH, (PubMed/MEDLINE’s controlled vocabulary indexing hierarchy), as well as a detailed examination of key terminology that would afford the best retrieval. Provisions were made to include varied constructs of search terms with the use of the asterisk as a truncation tool (Example: epidemiolog* to ensure retrieval of epidemiological, epidemiology, etc.) Additional constraints were also placed upon the final search strategy to limit the retrieval to English, humans, and studies published in the past 10 years at the time of the search (between 1999 and 2010).

Table 1 Prevalence of epilepsy in emerging markets

Following completion of the PubMed/MEDLINE search on January 4, 2011, the EMBASE and Cochrane databases were searched with comparable search strings on January 14, 2011 and January 18, 2011 respectively; duplicate citations, if present, were identified and removed. illustrates the various steps in the study selection process via a flow diagram. All citations were initially screened for relevancy and included where appropriate. Each abstract and, if needed, full-text article was reviewed for eligibility prior to inclusion in the current analysis. Reference lists of relevant studies identified by searching the three databases (PubMed/MEDLINE, EMBASE, and Cochrane) were further searched manually to identify any additional publications of interest. Articles were excluded if they did not focus on epilepsy, if they did not provide information about the outcomes of interest, if the sample size was <50, or if they pertained to infantile or pediatric populations <12 years old. Articles were excluded from this review if the articles were not published in English or if the subjects studied were not humans. Reviews, letters/comments, and case studies were also excluded from the review, but associated primary references were examined to verify they were identified by our search strategy. After abstracts were screened, full texts of the selected articles were reviewed to ensure relevance and presence of desired information.

Data abstraction

A structured abstraction table consisting of descriptive characteristics of the studies such as study objective/hypothesis; data collection methods (study design and analytics); study population characteristics (sample size, subject inclusion and exclusion criteria); treatments; outcomes; and limitations was used to extract the data from all relevant articles.

Results

Our comprehensive search yielded a total of 65 articles (). There were 16 articles found to have information relevant to epidemiology, four treatment guidelines, 33 articles which discussed treatment patterns, four articles discussing unmet needs, and eight economic articles. No articles were found addressing the topic of drug usage trends. Since many of the studies included in this review evaluated multiple topics, there was overlap between the categories. Therefore, many of the articles summarized below have been cross-categorized and, when totaled, the numbers of articles cited in each category add up to more than the 65 indicated.

Epidemiology of epilepsy

Prevalence

Studies were found describing the prevalence in Algeria, Argentina, Bahrain, China, Colombia, Comoros, Djibouti, Egypt, Eritrea, Gaza strip, India, Iraq, Jordan, Lebanon, Kuwait, Libya, Mauritania, Morocco, Oman, Qatar, Russia, Saudi Arabia, Somalia, Sudan, Syria, Taiwan, Tunisia, Turkey, United Arab Emirates, West Bank, and Yemen. These data are summarized in . Studies may provide data for lifetime prevalence, which approximate cumulative incidence, and/or active prevalence, which measures current seizures or current use of anti-epileptic drugs.

In the literature identified for this review, the prevalence of epilepsy in emerging markets varied according to the population studied. For example, three studies discussed the prevalence of epilepsy in Argentina. In the primary school children population, the lifetime and active prevalence rates were determined to be 3.2/1000 and 2.6/1000, respectively in one report, while lifetime and active prevalence was estimated to be 6.2/1000 and 3.8/1000 in another.Citation8,Citation9 Another examination found a lifetime prevalence of 71.9/1000 and an active prevalence of 64.8/1000 in the special schools of Buenos Aires that contain student populations with physical or mental disorders and learning problems.Citation10

The prevalence rate for active epilepsy in Saudi Arabia was reported in two separate studies. In the first, prevalence was found to be 6.54/1000 inhabitants.Citation11 A second study reported prevalence rates for several Arab countries. In this study, epilepsy prevalence ranged between 0.9/1000 in Sudan and 6.5/1000 in Saudi Arabia, reporting a median of 2.3/1000 inhabitants.Citation12

Three studies addressed the epidemiology of epilepsy in China. The prevalence of active epilepsy in China was estimated to be 1.52/1000 in one study and 1.54 per 1000 inhabitants in another.Citation13,Citation14 Hui and Kwan estimated that approximately 4.5/1000 individuals in Hong Kong have active epilepsy.Citation15 The lifetime and active prevalence rates of adult patients with epilepsy in Taiwan was estimated to be 3.14/1000 and 2.77/1000, respectively.Citation16

In Colombia, the general prevalence of epilepsy was determined to be 11.3/1000.Citation17 In India, they found that the age-specific prevalence of epilepsy in school-going children was 3.44/1000 for those aged 11–14 years and 2.33/1000 for those age 15–18 years.Citation18 In the Russian Federation, an age-adjusted prevalence of epilepsy of 3.40/1000 was reported.Citation19

Four studies examined the prevalence of epilepsy in Turkey with active rates ranging from 0.8/1000 to 8.5/1000 and lifetime rates from 5/1000 to 12.2/1000. Two separate studies found the active prevalence rate to be 0.08/1000, while in Bursa a prevalence rate for active epilepsy was 8.5/1000, and lifetime prevalence was reported to be 12.2/1000.Citation20–Citation22 Lastly, a lifetime prevalence of 6/1000 and an active epilepsy prevalence of 5/1000 was also reported.Citation23

Incidence

Only one study was identified that studied the incidence of epilepsy in emerging markets and it reported an annual incidence of 174 per 100,000 persons in Qatar in 2001.Citation12

Economics of epilepsy

Articles from Bulgaria, China, India, Korea and Mexico were identified. These data are summarized in and .

Table 2 Societal perspective – economic data

Table 3 Patient perspective – economic data

Societal perspective

From a societal perspective, costs due to loss of productivity averaged US$289 per patient per year in China ().Citation24 In India, the direct costs were calculated to be 147 rupees (US$3.26) to hospitals per epileptic patient, while the cost of monitoring therapeutic drugs to the hospital, per seizure prevented, was 22.35 rupees (US$0.50).Citation25

Payer perspective

In Korea, from the payer’s perspective, adjunctive therapy led to the incremental cost-effectiveness ratios being estimated at US$44 per seizure-free day per adult patient and US$11,084 per quality-adjusted life years gained.Citation26

Patient perspective

From a patient perspective, Bulgarian patients with one or two adverse events (AEs) had significantly lower annual costs (mean €338.73) than those with more than two AEs (mean €806.03) while taking AED monotherapy (). Monotherapy patients with fewer seizures also showed significantly lower costs (mean €85.97), compared with patients with more frequent seizures (mean €810.43). Patients on AED therapy, with 50% or more seizure reduction compared with baseline, showed significantly lower costs (mean 402.67€) than those with worse control (mean €931.30).Citation27

In rural Shanghai and Ningxia, China, the total 1-year expenses per patient before AED treatment were 1494.30¥ (US$229) and 213.09¥ (US$33), respectively, and these expenses decreased to 91.52¥ (US$14) and 45.90¥ (US$7), respectively (P < 0.05) following treatment for 1 year.Citation28 In another study from China, direct medical care costs were 2529¥ (US$372) per year per patient, of which anti-epileptic drugs (1651¥ or US$243) accounted for the major cost component.Citation24 Nonmedical direct costs were much less than direct health care costs, averaging approximately 756¥ (US$111). The overall mean annual cost for epilepsy per patient in this series was approximately 5253¥ (US$773), and these costs accounted for more than half of the mean annual income.Citation24

In India, direct costs were calculated, including cost to the hospital of providing the therapeutic drug monitoring (TDM) service, cost to the hospital per seizure prevented, and cost to the patient per seizure prevented.Citation25 The cost per patient of the TDM service to the hospital was 147 rupees (US$3.26), while each patient was charged only 30 rupees (US$0.67) per sample, reflecting the cost of the consumables only. The cost of TDM to the hospital per seizure prevented was 22.35 rupees (US$0.50) while the cost to the patient was 4.50 rupees (US$0.10). A second study found that the cost of drug therapy for patients at entry ranged from 2276 rupees (US$50.46) to 3629 rupees (US$80.46). At the time of last follow-up, it ranged from 1898 rupees (US$42.08) to 4929 rupees (US$109.28).Citation29

Lastly, in Mexico, the annual mean health care cost per treated patient was found to be US$2646. Ambulatory health care contributed to 76% of the total, and hospital health care contributed 24%.Citation30

Treatment guidelines

The goal of epilepsy treatment is to maintain a normal lifestyle, ideally, by complete seizure control with minimal side effects. For the majority of patients with epilepsy, AED therapy is used. The quality of care and therapeutic outcome may differ across countries because of numerous variations in medical systems. Few additional studies were identified that addressed ways by which care providers could more effectively identify patients with epilepsy or determine an appropriate therapy.

In China, age-varying differences between the effectiveness of carbamazepine and valproate for the treatment of generalized onset and partial onset seizures were reported in a study that suggested valproate may be more effective at treating epilepsy in younger patients, while carbamazepine may be more effective at treating patients older than 30.Citation31 An electroencephalography screening process by which high-risk patients can be better screened was described as well as a method used to aid health care providers in the identification of patients with generalized tonic-clonic seizures.Citation32,Citation33

Treatment patterns

In the articles identified, data on the treatment patterns of 12,317 patients with generalized or partial onset epilepsy were found for countries including Argentina, Brazil, China, Czech Republic, India, Korea, Poland, Russia, and Taiwan. These data are summarized in . Seventeen different AEDs were used in these studies. The proportion of patients receiving each AED was phenobarbital (21.7%), valproate (17.5%), tiagabine (16.4%), oxcarbazepine (8.3%), levetiracetam (8.1%), topiramate (7.2%), eslicarbazepine acetate (5.8%), lacosamide (3.9%), lamotrigine (2.1%), pregabalin (1.9%), and clobazam (1.6%). Zonisamide, primidone, clonazepam, phenytoin, gabapentin, and carbamazepine were used in <1% of the population each. In all studies, the use of these AEDs resulted in an increase of patients who became seizure free and a reduction of seizure frequency and severity.

Table 4 Clinical trials of therapies for epilepsy

Unmet needs

The literature review identified five articles discussing the unmet needs of patients with epilepsy in emerging markets. There were two studies of the Indian population and one study found for each of the countries of Bahrain, the Czech Republic, and Kuwait. In general, the articles identified the need for developing treatment strategies, counseling therapies, and social support for people with epilepsy to improve their quality of life.Citation34,Citation35 As the mean delay in diagnosis is 1.5 ± 4 years in parts of India, facilities for epilepsy surgery, therapeutic drug monitoring, and services of clinical psychologist or medical social workers are also needed.Citation36 In Kuwait, objections to shaking hands with, working with, marrying, and employing patients with epilepsy were reported by 16.0%, 24.8%, 71.6%, and 45.2%, of the general population, respectively.Citation37 Therefore, continuing effective educational interventions are needed to improve the understanding of epilepsy and to diminish social discrimination and misconceptions against these patients.Citation37

Discussion

This review is a thorough study of epilepsy in emerging markets summarizing the available literature on epidemiology, economics, unmet needs, treatment and drug usage patterns, and guidelines for the treatment of epilepsy in emerging markets. To more fully grasp the information found in this review concerning epilepsy and its treatment in emerging markets, it is useful to compare these findings to data from developed countries with higher per capita incomes.

Because it is often less complicated to obtain information regarding prevalence than incidence, many more prevalence studies of epilepsy from diverse populations were found. In general, prevalence rates per 1000 individuals varied widely in this review. In Argentina and China, rates ranged from 2.6–3.8 and 1.5–4.5 respectively.Citation8,Citation9,Citation13,Citation15 In India, prevalence was reported to be 2.3 and in Turkey, rates ranged from 0.08 to 8.5 individuals.Citation18,Citation20,Citation22 Studies from Argentina reported a wide range of per 1000 population rates of 3.2, 6.2, and 71.9 in the general school, general, and the special school populations, respectively. The prevalence study from southern Sudan was based on a population estimate of ‘50–100,000’ making comparisons to other countries impractical.Citation12 Yet, the general prevalence of epilepsy in Colombia was determined to be 11.3/1000 which was reported to be similar to prevalence rates found in nations with comparable developmental status.Citation17

In developed countries, prevalence rates for epilepsy have been reported to range from 0.027–0.1 per 1000 individuals.Citation38,Citation39 It is generally accepted that the prevalence rate in developing countries is approximately double that of developed countries, at approximately 0.15/1000.Citation40 Variation in rates, between and within studies, may be attributable to differences in definitions of epilepsy and prevalence. For example, in the study by Banerjee and colleagues,Citation38 the reported age-adjusted prevalence was based on medical records, whereas Onal and colleagues, used self-reported prevalence which was not confirmed by medical diagnoses.Citation20 Yet, as prevalence is also a measure of the interaction of additional factors such as death, incidence, remission of illness, population migration, or access to appropriate medical care, it is likely that numerous factors account for the differences found between world populations, and not just differing methodologies. Population screening is needed to reveal the true epilepsy prevalence. Until broader, countrywide studies are performed, epidemiological rates will tend to be underestimated.

Incidence rates for North America and Europe have been reported to range from 16–51 per 100,000 people.Citation38,Citation39,Citation41 These rates are at the lower end of global annual incidence estimates of 50–70 cases per 100,000.Citation42 Only one study was identified in our review reporting an incidence of 174 per 100,000 persons in Qatar.Citation12 However, this incidence study was regional, retrospective, hospital-based, and did not have a clear definition of epilepsy. Interpretation of the differences in incidence and prevalence rates will require additional awareness of the role of economic, cultural, and social factors effecting epilepsy and its care in these markets.

The primary focus of care for patients with epilepsy is the prevention of further seizures which may lead to additional morbidity or mortality.Citation43 The goal of treatment is the maintenance of a normal lifestyle, ideally by complete seizure control without, or with, minimal side effects. If seizures are provoked by external factors, avoidance might be sufficient to prevent attacks. However, for the majority of patients, AED therapy is used. In addition to seizure control, patients with epilepsy may have psychosocial symptoms requiring treatment. But the quality of care and therapeutic outcome may differ across countries because of variations in medical systems. The Commission of European Affairs of the International League Against Epilepsy has defined standards for appropriate care,Citation44 which have not yet been met by some European countries.Citation45 As such, the situation in many developing countries is frequently less adequate. Few studies were identified that addressed ways by which care providers could more effectively identify patients with epilepsy or suggest an appropriate therapy, but in the studies reviewed for this report, the use of AEDs resulted in an increase of patients who had a decreased seizure burden.

In 2005, Garcia-Contreras et al reported the annual health care cost per treated patient in Mexico to be US$2646.Citation30 In the US, this number has been reported to be in the range of US$2600–9400 per person.Citation46,Citation47 It should be noted, however, that these values from the year 2000 provide an outdated estimate of the direct costs of epilepsy, and it is reasonable to assume that in current monetary terms this burden is greater. Again, the differences between regions may be due to multiple factors including an underestimation of the affected population due to limited resources or, perhaps, the use of less expensive generic drugs over branded products. In 1999, phenytoin (dilantin) had a 42% market share of all AED prescriptions in the US.Citation48 The introduction of new AEDs over the past decade, including gabapentin, felbamate, lamotrigine, tiagabine, and topiramate, has increased the options available for adjunctive treatment when first-line therapy is ineffective. Many of these newer medications, however, often have increased tolerability and are beginning to replace their preceding agents as first-line therapy.Citation48 In fact, in 2004, phenytoin’s US market share had dropped to 33%.Citation48 Yet, while the newer, branded medications are available in many emerging markets, resources are often limited and the inexpensive, effective generic AEDs are often used out of necessity. For example, Mani et al demonstrated successful treatment of epilepsy in a rural area of India using a combination of trained physicians and health workers, generic AEDs, drug compliance, health education, and follow-up.Citation49 Further analyses considering cost-minimization, cost-effectiveness, and cost-benefit must be done in the future to further understand the cost of epilepsy therapy to resource-poor regions.

Epilepsy care in developing countries lags behind care in developed countries. Precise data on delivery of neurological services for epilepsy is vital to optimize medical services for patients with limited resources. This review additionally highlighted the need for the development of treatment strategies, counseling therapies, and social support services for people with epilepsy.Citation34 Facilities for epilepsy surgery, therapeutic drug monitoring, and clinical psychologist or medical social worker services are also needed, as are educational interventions to improve the awareness of epilepsy misconceptions, and to end social discrimination against patients with epilepsy.Citation36,Citation37

Other limitations must be considered when evaluating the literature described in this review. One limitation of some of the literature included in this review is study design. Most of the evidence was derived from retrospective analyses of observational, uncontrolled studies. These study designs cannot lead to conclusions regarding causality, but rather provide correlative evidence. Sample sizes were generally large, however, the lack of statistical differences in certain factors found in some studies may have been due to an insufficient number of subjects in treatment groups. Additionally, selection and treatment bias towards individuals residing in a particular geographical region was inherent to some studies. Another limitation of this literature review was that results were limited to English. Some of the objectives (eg, treatment patterns, epidemiology) might have been explored in more detail in older literature and therefore would not have been captured in our search. Our search strategy also focused on peer-reviewed publications and did not capture information from abstracts, posters, or dissertations, which may have limited the amount of information assessed for this review. Lastly, all literature reviews are limited by publication bias with regard to the articles that are available.

Conclusion

This paper is an exhaustive examination of published literature describing many aspects of epilepsy in emerging markets. Overall, the reported incidence of epilepsy is low in the general population and, overall, treating patients with epilepsy is inexpensive and decreases the use of health care resources.

However, the identified clinical studies generally lacked standardized diagnosis criteria and used ineffectual methods with which to grade symptoms. Standards of care and baseline medications varied greatly between populations and adjunctive medications were often arbitrarily examined. Studies with longer follow-up periods and larger patient populations are needed to document the long-term effectiveness of several AEDs. Many of the observations discussed in this review need to be further confirmed in larger prospective trials, and, looking for specific characteristics of patients responding to certain drugs may lead to useful guidelines for drug choice in treating epilepsy. Knowledge gained in these areas will enable improvement to the care of people with epilepsy both in emerging markets and elsewhere.

Disclosure

The authors declare no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- Epilepsy Fact Sheet No 999,12009World Health Organization 2009. Available at: http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs999/en/index.html. Accessed on September 27, 2011.

- Proposal for revised classification of epilepsies and epileptic syndromes. Commission on Classification and Terminology of the International League Against EpilepsyEpilepsia19893043893992502382

- SchachterSCSeizure disordersMed Clin North Am200993234335119272512

- FrenchJAKannerAMBautistaJEfficacy and tolerability of the new anti-epileptic drugs II: Treatment of refractory epilepsyNeurology20046281261127315111660

- HeakalRWhat Is An Emerging Market Economy?2009 Available at: http://www.investopedia.com/articles/03/073003.asp#axzz1Z4eUuEFk. Accessed on April 20, 2011.

- NewtonCRStatus epilepticus in resource-poor countriesEpilepsia20095012545519941526

- International League Against Epilepsy [homepage] Available at: www.ilae-epilepsy.org. Accessed on April 20, 2011.

- SomozaMJForlenzaRHBrussinoMLicciardiLEpidemiological survey of epilepsy in the primary school population in Buenos AiresNeuroepidemiology2005252626815947492

- MelconMOKochenSVergaraRHPrevalence and clinical features of epilepsy in Argentina. A community-based studyNeuroepidemiology200728181517164564

- SomozaMJForlenzaRHBrussinoMCenturiónEEpidemiological survey of epilepsy in the special school population in the city of Buenos Aires. A comparison with mainstream schoolsNeuroepidemiology200932212913519088485

- Al RajehSAwadaABademosiOOgunniyiAThe prevalence of epilepsy and other seizure disorders in an Arab population: a community-based studySeizure200110641041411700993

- BenamerHTGrossetDGA systematic review of the epidemiology of epilepsy in Arab countriesEpilepsia200950102301230419389149

- KwongKLChakWKWongSNSoKTEpidemiology of childhood epilepsy in a cohort of 309 Chinese childrenPediatr Neurol200124427628211377102

- FongGCMakWChengTSChanKHFongJKHoSLA prevalence study of epilepsy in Hong KongHong Kong Med J20039425225712904612

- HuiACLamJMWongKSKayRPoonWSVagus nerve stimulation for refractory epilepsy: long term efficacy and side-effectsChin Med J (Engl)20041171586114733774

- ChenCCChenTFHwangYCPopulation-based survey on prevalence of adult patients with epilepsy in Taiwan (Keelung community-based integrated screening no.12)Epilepsy Res2006721677416938434

- VelezAEslava-CobosJEpilepsy in Colombia: epidemiologic profile and classification of epileptic seizures and syndromesEpilepsia200647119320116417549

- ShahPAShapooSFKoulRKKhanMAPrevalence of epilepsy in school-going children (6–18 years) in Kashmir Valley of North-west IndiaJ Indian Med Assoc2009107421621819810364

- HalászPCramerJAHodobaDBIA-2093-301 Study GroupLong-term efficacy and safety of eslicarbazepine acetate: results of a 1-year open-label extension study in partial-onset seizures in adults with epilepsyEpilepsia201051101963196920662896

- OnalAETumerdemYOzturkMKEpilepsy prevalence in a rural area in IstanbulSeizure200211639740112160670

- SerdaroğluAOzkanSAydinKGücüyenerKTezcanSAycanSPrevalence of epilepsy in Turkish children between the ages of 0 and 16 yearsJ Child Neurol200419427127415163093

- CalisirNBoraIIrgilEBozMPrevalence of epilepsy in Bursa city center, an urban area of TurkeyEpilepsia200647101691169917054692

- VeliogluSKBakirdemirMCanGTopbasMPrevalence of epilepsy in northeast TurkeyEpileptic Disord2010121223720207601

- HongZQuBWuXTYangTHZhangQZhouDEconomic burden of epilepsy in a developing country: a retrospective cost analysis in ChinaEpilepsia200950102192219819583782

- RaneCTDalviSSGogtayNJShahPUKshirsagarNAA pharmacoeconomic analysis of the impact of therapeutic drug monitoring in adult patients with generalized tonic-clonic epilepsyBr J Clin Pharmacol200152219319511488777

- SuhGHLeeSKEconomic Evaluation of Add-on Levetiracetam for the Treatment of Refractory Partial Epilepsy in KoreaPsychiatry Investig200963185193

- BalabanovPPZaharievZIMatevaNGEvaluation of the factors affecting the quality of life and total costs in epilepsy patients on monotherapy with carbamazepine and valproateFolia Med (Plovdiv)2008502182318702221

- DingDHongZChenGSPrimary care treatment of epilepsy with phenobarbital in rural China: cost-outcome analysis from the WHO/ ILAE/IBE global campaign against epilepsy demonstration projectEpilepsia200849353553918302628

- ThomasSVKoshySNairCRSarmaSPFrequent seizures and polytherapy can impair quality of life in persons with epilepsyNeurol India2005531465015805655

- Garcia-ContrerasFConstantino-CasasPCastro-RiosADirect medical costs for partial refractory epilepsy in MexicoArch Med Res200637337638316513488

- CowlingBJShawJEHuttonJLMarsonAGNew statistical method for analyzing time to first seizure: example using data comparing carbamazepine and valproate monotherapyEpilepsia20074861173117817553118

- KochenSGiaganteBOddoSSpike-and-wave complexes and seizure exacerbation caused by carbamazepineEur J Neurol200291414711784375

- AnandKJainSPaulESrivastavaASahariahSAKapoorSKDevelopment of a validated clinical case definition of generalized tonic-clonic seizures for use by community-based health care providersEpilepsia200546574375015857442

- OtoomSAl-JishiAMontgomeryAGhwanmehMAtoumADeath anxiety in patients with epilepsySeizure200716214214617126569

- TlustaEZarubovaJSimkoJHojdikovaHSalekSVlcekJClinical and demographic characteristics predicting QOL in patients with epilepsy in the Czech Republic: how this can influence practiceSeizure2009182858918644739

- ThomasSVSarmaPSAlexanderMEpilepsy care in six Indian cities: a multicenter study on management and serviceJ Neurol Sci20011881–2737711489288

- AwadASarkhooFPublic knowledge and attitudes toward epilepsy in KuwaitEpilepsia200849456457218205820

- BanerjeePNFilippiDAllen HauserWThe descriptive epidemiology of epilepsy-a reviewEpilepsy Res2009851314519369037

- TheodoreWHSpencerSSWiebeSEpilepsy in North America: a report prepared under the auspices of the global campaign against epilepsy, the International Bureau for Epilepsy, the International League Against Epilepsy, and the World Health OrganizationEpilepsia200647101700172217054693

- StrzelczykAReeseJPDodelRHamerHMCost of epilepsy: a systematic reviewPharmacoeconomics200826646347618489198

- CrossSACurranMPLacosamide: in partial-onset seizuresDrugs200969444945919323588

- StephenLJBrodieMJPharmacotherapy of epilepsy: newly approved and developmental agentsCNS Drugs20112528910721254787

- KwanPBrodieMJClinical trials of antiepileptic medications in newly diagnosed patients with epilepsyNeurology20036011 Suppl 4S2S1212796516

- BrodieMJShorvonSDCangerRCommission on European Affairs: appropriate standards of epilepsy care across Europe. ILEAEpilepsia19973811124512509579928

- MalmgrenKFlinkRGuekhtABILAE Commission of European Affairs Subcommission on European Guidelines 1998–2001: The provision of epilepsy care across EuropeEpilepsia200344572773112752475

- BegleyCEFamulariMAnnegersJFThe cost of epilepsy in the United States: an estimate from population-based clinical and survey dataEpilepsia200041334235110714408

- WiebeSBurden of intractable epilepsyAdv Neurol2006971416383108

- UthmanBMBeydounALess commonly used antiepileptic drugsThe treatment of epilepsy: principles and practice4 edBaltimore, MDLippincott, Williams and Wilkins2006947

- ManiKSRanganGSrinivasHVSrindharanVSSubbakrishnaDKEpilepsy control with phenobarbital or phenytoin in rural south India: the Yelandur studyLancet200135792651316132011343735

- MontenegroMACendesFNoronhaALEfficacy of clobazam as add-on therapy in patients with refractory partial epilepsyEpilepsia200142453954211440350

- MontenegroMAFerreiraCMCendesFLiLMGuerreiroCAClobazam as add-on therapy for temporal lobe epilepsy and hippocampal sclerosisCan J Neurol Sci2005321939615825553

- LiuLZhangQYaoZThe operational model of a network for managing patients with convulsive epilepsy in rural West ChinaEpilepsy Behav2010171758119910259

- LuYWangXLiQLiJYanYTolerability and safety of topiramate in Chinese patients with epilepsy: an open-label, long-term, prospective studyClin Drug Investig20072710683690

- LuYXiaoZYuWEfficacy and safety of adjunctive zonisamide in adult patients with refractory partial-onset epilepsy: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trialClin Drug Investig2011314221229

- LuYYuWWangXEfficacy of topiramate in adult patients with symptomatic epilepsy: an open-label, long-term, retrospective observationCNS Drugs200923435135919374462

- SunMZDeckersCLLiuYXWangWComparison of add-on valproate and primidone in carbamazepine-unresponsive patients with partial epilepsySeizure2009182909318672385

- WuXYHongZWuXMulticenter double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled trial of levetiracetam as add-on therapy in Chinese patients with refractory partial-onset seizuresEpilepsia200950339840518657175

- XiaoZLiJMWangXFEfficacy and safety of levetiracetam (3,000 mg/Day) as an adjunctive therapy in Chinese patients with refractory partial seizuresEur Neurol200961423323919176965

- TranKTHranickyDLarkTJacobNJGabapentin withdrawal syndrome in the presence of a taperBipolar Disord20057330230415898970

- SethiAChandraDPuriVMallikaVGabapentin and lamotrigine in Indian patients of partial epilepsy refractory to carbamazepineNeurol India200250335936312391470

- HalászPKälviäinenRMazurkiewicz-BełdzińskaMSP755 Study GroupAdjunctive lacosamide for partial-onset seizures: Efficacy and safety results from a randomized controlled trialEpilepsia200950344345319183227

- ElgerCHalászPMaiaJAlmeidaLSoares-da-SilvaPBIA-2093-301 Investigators Study GroupEfficacy and safety of eslicarbazepine acetate as adjunctive treatment in adults with refractory partial-onset seizures: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, parallel-group phase III studyEpilepsia200950345446319243424

- JedrzejczakJKuncikováMMagureanuSVIPe Study GroupAn observational study of first-line valproate monotherapy in focal epilepsyEur J Neurol2008151667218042239

- DeleuDAl-HailHMesraouaBMahmoudHAGulf Vipe Study GroupShort-term efficacy and safety of valproate sustained-release formulation in newly diagnosed partial epilepsy VIPe-study. A multicenter observational open-label studySaudi Med J20072891402140717768469

- KwanPLimSHChinvarunYCabral-LimLAzizZALoYKEfficacy and safety of levetiracetam as adjunctive therapy in adult patients with uncontrolled partial epilepsy: the Asia SKATE II StudyEpilepsy Behav2010181–210010520462804

- BarcsGWalkerEBElgerCEOxcarbazepine placebo-controlled, dose-ranging trial in refractory partial epilepsyEpilepsia200041121597160711114219

- ChmielewskaBStelmasiakZGABI-balance – a non-interventional observational study on the effectiveness of tiagabine in add-on therapy in partial epilepsyNeurol Neurochir Pol200842430331118975234

- JedrzejczakJTiagabine as add-on therapy may be more effective with valproic acid – open label, multicentre study of patients with focal epilepsyEur J Neurol200512317618015693805

- MajkowskiJNetoWWapenaarRVan OeneJTime course of adverse events in patients with localization-related epilepsy receiving topiramate added to carbamazepineEpilepsia200546564865315857429

- Mazurkiewicz-BeldzinskaMSzmudaMMatheiselALong-term efficacy of valproate versus lamotrigine in treatment of idiopathic generalized epilepsies in children and adolescentsSeizure201019319519720167512

- BondarenkoIIExperience in the use of the anticonvulsant pregabalin as an add-on therapy in patients with partial epilepsy with polymorphic seizuresNeurosci Behav Physiol201040216316420033307

- BurdSGGlukhovaLIBadalianOLEfficacy and safety of the mono- and combined therapy with oxcarbazepine in adult patientsZh Nevrol Psikhiatr Im S S Korsakova201011066669 Russian.20559277

- ZheleznovaEVKalininVVZemlyanayaAASokolovaLVMedvedevILMonotherapy of epilepsy in women: psychiatric and neuroendocrine aspectsNeurosci Behav Physiol201040215716220033304

- ChoYJHeoKKimWJLong-term efficacy and tolerability of topiramate as add-on therapy in refractory partial epilepsy: an observational studyEpilepsia20095081910191919563348

- HeoKLeeBIYiSDEfficacy and safety of levetiracetam as adjunctive treatment of refractory partial seizures in a multicentre open-label single-arm trial in Korean patientsSeizure200716540240917369059

- KimYDHeoKParkSCAntiepileptic drug withdrawal after successful surgery for intractable temporal lobe epilepsyEpilepsia200546225125715679506

- LeeBIYiSHongSBPregabalin add-on therapy using a flexible, optimized dose schedule in refractory partial epilepsies: a double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled, multicenter trialEpilepsia200950346447419222545

- HuangCWPaiMCTsaiJJComparative cognitive effects of levetiracetam and topiramate in intractable epilepsyPsychiatry Clin Neurosci200862554855318950374

- TsaiJJYenDJHsihMSEfficacy and safety of levetiracetam (up to 2000 mg/day) in Taiwanese patients with refractory partial seizures: a multicenter, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled studyEpilepsia2006471728116417534