Abstract

Background

The purpose of this study was to investigate the impact of dosing frequency on adherence in severe chronic psychiatric and neurological diseases.

Methods:

A systematic literature review was conducted for articles in English from medical databases. Diseases were schizophrenia, psychosis, epilepsy, bipolar disorder, and major depressive disorder.

Results:

Of 1420 abstracts screened, 12 studies were included. Adherence measures included Medication Event Monitoring System (MEMS®), medication possession ratio, medication persistence, and refill adherence. Three schizophrenia and one epilepsy study used MEMS, and all showed a trend towards higher adherence rates with less frequent dosing regimens. Three depression and one schizophrenia study used the medication possession ratio; the pooled odds ratio of being adherent was 89% higher (ie, 1.89, 95% credibility limits 1.71–2.09) on once-daily versus twice-daily dosing. Two studies in depression and one in all bupropion patients assessed medication persistence and refill adherence. The pooled odds ratio for the two depression studies using medication persistence was 2.10 (95% credibility limits 1.86–2.37) for once-daily versus twice-daily dosing. For refill adherence after 9 months, 65%–75% of patients on once-daily versus 56% on twice-daily dosing had at least one refill. In all but one of the studies using other measures of adherence, adherence rates were higher with once-daily dosing compared with more frequent dosing regimens. No relevant studies were identified for bipolar disorder or psychosis.

Conclusion:

Differences in study design and adherence measures used across the studies were too large to allow pooling of all results. Despite these differences, there was a consistent trend of better adherence with less frequent dosing.

Introduction

Chronic illnesses such as schizophrenia, epilepsy, and major depressive disorder (depression), are characterized by their need for long-term care and their severe impact on patients and their families, health care systems, and society. They affect a large proportion of the population; approximately 26.3 million people have schizophreniaCitation1 and around 50 million have epilepsy worldwide,Citation2,Citation3 while in most countries 8%–12% of all inhabitants are estimated to suffer from depression in their lifetime.Citation4,Citation5 Disease management with long-term treatment includes the use of typical or atypical antipsychotic medication for schizophrenia, antiepileptics for epilepsy, and antidepressants (often with psychotherapy and counseling) for depression. Because these disorders are chronic and/or relapsing, adherence to prescribed drug therapies is a key to relapse prevention and sustained treatment success. The term adherence describes the extent to which a patient takes medication as prescribed with respect to dosage and dosing intervals.Citation6

Nonadherence can have considerable negative clinical and economic consequences. For instance, patients with schizophrenia who discontinue antipsychotic medication are at increased risk of symptom exacerbation and poor functional outcomes, as well as relapse and hospitalization.Citation7 In one recent review evaluating adherence in schizophrenia, patients with schizophrenia receiving antipsychotic medication took less than 60% of their prescribed dose, and up to 75% of patients were noncompliant by the second year of treatment.Citation8 Medication nonadherence was the strongest predictor of relapse, with an odds ratio of 7.6.Citation9

In epilepsy, adherence to antiepileptic medication is critical in preventing or minimizing seizures.Citation10 Increased seizure frequency can have serious repercussions on quality of life,Citation2,Citation3 as well as increased utilization and costs for inpatient and emergency services.Citation11–Citation13 In depression, 28% of patients on antidepressant medication discontinued use within the first month and at least 40% by 3 months in a major depressive disorder study.Citation14 That study also found early drug discontinuation to be associated with a 77% increase in the risk of relapse, which ultimately resulted in higher health care costs.Citation14

Nonadherence can be intentional, due to patients’ own poor expectations of treatment, side effects, or lifestyle choice, or not intentional, when patients fail to adhere through forgetfulness, misunderstanding, or uncertainty about clinicians’ recommendations. A wide range of factors affect adherence, and can be classified into disease-related drivers, patient-related drivers, treatment-related drivers, and environment-related drivers. Therefore, a wide range of methods has been used to assess adherence in various studies.

Dosing complexity (or increased dosing frequency) may contribute to poor medication adherence in chronic illnesses such as schizophrenia, epilepsy, and depression. The assumption that once-daily dosing improves a patient’s adherence to therapy compared with more frequent daily dosing regimens has been studied in prospective studies (eg, using pill countCitation15,Citation16 or Medication Event Monitoring System [MEMS®]Citation15–Citation18 as well as retrospective database studies eg, using the medication possession ratio [MPR]Citation19–Citation22 and drug persistence).Citation19,Citation21,Citation22 Efforts to provide greater objectivity and uniformity in measuring adherence have led to the use of MEMS, a medication bottle cap with a microprocessor that records the occurrence and time of each bottle opening, which has been used in several mental health studies (ie, in schizophrenia,Citation16–Citation18,Citation23 depression,Citation23,Citation24 and Parkinson’s disease)Citation25 as well as for other medical conditions (ie, for AIDS,Citation26 hypertension,Citation27 and liver transplantation).Citation28

Given that improving adherence is clinically highly relevant, and simplifying dosing schedules is seen as one way to meet this end a systematic review of the link between dosing frequency and adherence is warranted. To our knowledge, no such systematic review currently exists. Specifically, there are no assessments of the pooled quantitative effect of increased dosing frequency on adherence. The primary objective of this study was to perform a systematic literature review to assess the relationship between dosing frequency (specifically once-daily versus multiple daily dosing) and adherence (irrespective of how it was measured) in patients with chronic psychiatric and neurological diseases in the form of schizophrenia, psychosis, epilepsy, depression, and bipolar disorder. A secondary objective was to pool the results in a meta-analysis, if possible.

Materials and methods

A systematic search of the literature was conducted for English language articles in MEDLINE, MEDLINE In-Process (MEIP) and EMBASE (using OVID) and the Cochrane Library (CCTR [Central Register of Controlled Trials] and DARE [The Database of Abstracts of Reviews of Effects]). No date restrictions were applied to the search. The search used free text and MeSH terms to identify studies in the following diseases: schizophrenia and disorders with psychotic features, psychosis, epilepsy, bipolar disorder, and major depressive disorder (depression). The disease terms were then combined with terms for the outcomes of interest, which were adherence/compliance/persistence and dosing frequency. Given an expected paucity of data on this topic, no restriction was applied as to specific measurements of adherence. The search did not include abstracts from conferences. The search was conducted according to PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses) guidelines for systematic literature reviews and meta-analysis. The search strategy (OVID) is presented in .

Table 1 Search strategy (OVID)

Abstracts were screened by two researchers independently for relevance to this study. Full-text publications that were potentially relevant were then screened for inclusion against the following predetermined criteria:

Population (chronic psychiatric and neurological diseases [see above], adults)

Interventions (oral treatments)

Comparison treatments (once a day versus multiple times daily)

Outcomes (medication compliance, adherence, or persistence rates)

Study design (prospective or retrospective observational studies, randomized clinical trials [Phase II or III], or meta-analyses).

The feasibility of pooling results in a meta-analysis was assessed based on the similarity of study designs, patient characteristics, and definition of outcomes used. In the case of large differences, a qualitative comparison was made instead. For mixed treatment comparison, a fixed-effects modelCitation29,Citation30 or a random-effects modelCitation29,Citation30 can be used. The fixed-effects model assumes that the differences in estimated relative treatment effects across studies in the network of evidence are only caused by random variation. The random-effects model assumes that the differences in estimated relative treatment effects are caused by random variation as well as by variation in the true treatment effect.

For the quantitative analyses, a fixed-effects model for mixed treatment comparison was used because this was the most appropriate model for analyzing a small number of studies. Random effects models were not used due to the limited number of studies (ie, two to four studies depending on the scenario). Odds ratios were calculated for certain adherence measures (eg MPR) where they were not reported in the original publication. Several scenario analyses were performed with inclusion of different patient populations. For each scenario, the pooled odds ratio (OR) was calculated, together with the corresponding 95% credibility limits (CrL) as a measure of uncertainty.

Results

Identification of studies

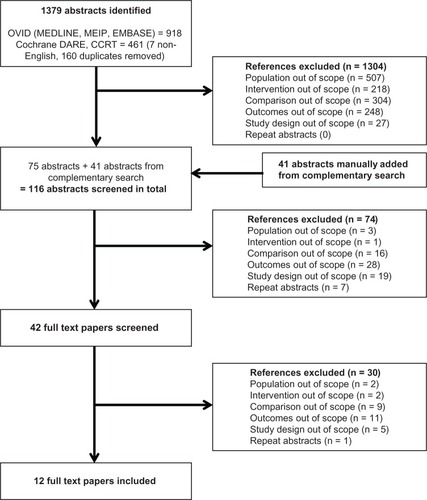

The OVID and Cochrane Library searches (CCTR and DARE) identified 1379 abstracts in total. Forty-one abstracts that were published separately were manually added. Of the 1420 abstracts that were screened, 42 potentially relevant full-text publications were selected for a second screening, and 12 full papers were included in the final review. presents the flow chart of identified studies.

Assessment of included studies

The studies included were compared in terms of adherence outcomes used, patient population, study design, and dosing frequency comparisons. An overview of the different adherence measures and associated studies is found in , whereas provides a detailed presentation of study characteristics and main outcomes.

Table 2 Overview of different adherence measures per study

Table 3 Characteristics of studies included

Various adherence outcome measures were used (). Four studiesCitation15–Citation18 reported the results recorded by MEMS. Four studiesCitation19–Citation22 reported MPR of which three studies also reported refill adherenceCitation19,Citation21,Citation22 and medication persistence.Citation19,Citation21,Citation22 Another four studies used a different outcome measure that did not allow further comparison: Doughty et alCitation31 used four questions to assess levels of adherence (eg, “never miss a dose” to “miss once a week or more”); Zaccara et alCitation32 compared mean drug plasma levels with different dosing frequencies; Cramer et alCitation33 assessed the odds of missing a dose with different dosing frequencies; and Meier et alCitation34 used the Medication Adherence Questionnaire (MAQ) and Clinician Rating Scale (CRS) to assess adherence. Remington et alCitation16 used clinician rating as a measure of adherence.

In terms of patient populations, there were four studies in epilepsy,Citation15,Citation31–Citation33 five studies in schizophrenia,Citation16–Citation18,Citation20,Citation34 and three studies in depressionCitation19,Citation21,Citation22 (although one of these evaluated any patient treated with bupropion extended release (XL) or sustained release (SR) which may have included other conditionsCitation21). The mean patient age was fairly comparable across studies, ranging from 35 to 45 years, except for one study in schizophrenia in which patients had a mean age of 55 years.Citation20 Looking at the gender distribution of patients in the trials, the majority of patients in the depression studiesCitation19,Citation21,Citation22 were women (around 64%–70%) compared with the epilepsy studies,Citation15,Citation31–Citation33 where approximately half of the population were women (50%–53%). Two epilepsyCitation15,Citation33 studies did not report the number of women. The proportion of women in depression studies was high when compared with the schizophreniaCitation16,Citation18,Citation20,Citation34 studies where women were in a minority (5%–50%), while DiazCitation17 did not report the number of women.

Study design varied according to the adherence outcome measure used. The four studies assessing MEMSCitation15–Citation18 were small prospective studies which included between 25 and 100 patients, with a follow-up period of 1–4.5 months. The four studies assessing MPRCitation19–Citation22 (including three assessing refill adherenceCitation19,Citation21,Citation22 and persistence)Citation19,Citation21,Citation22 were large retrospective US database studies with patient numbers between 2991 and 269,517 and study periods of 9 months to one year. The four remaining studiesCitation31–Citation34 were international studies that applied various adherence measures and included small and large studies and surveys, as well as retrospective and prospective designs.

Most of the studies were conducted in the US,Citation15–Citation24 one study was performed in Canada,Citation16 one was performed in Italy,Citation32 two were international studies (one was performed in four countries [The Netherlands, United Kingdom, Italy and Germany],Citation34 and the other was performed in eight countries [Germany, Bulgaria, Hungary, Latvia, Romania, Russia, Spain, and India]).Citation31

Four studiesCitation18,Citation19,Citation21,Citation22 compared once-daily dosing with twice-daily dosing; six studiesCitation15–Citation17,Citation32–Citation34 compared once-daily with twice-daily dosing, three times daily, or four times daily dosing; a schizophrenia studyCitation20 compared once-daily with more than once-daily dosing; and a study in epilepsyCitation31 compared once-daily versus twice-daily and more than twice-daily dosing.

Definitions of adherence measures used

The following adherence measures were used in more than one study and allowed comparisons to be made. MEMS measured the number of bottle openings during a given time period so that the proportion of the prescribed or expected number of bottle openings that actually occurred could be estimated. A patient was arbitrarily deemed to be nonadherent in the studies if the MEMS score was under 70%,Citation18 under 80%,Citation16 or if a scheduled dose was omitted.Citation15 Because the study duration varied and longer duration studies are expected to have worse adherence outcomes, the period over which MEMS scores were assessed was not comparable.

MPR estimated the days of medication supply the patient has taken for the duration prescribed or required. A MPR of 1.0 indicates full adherence,Citation35 whereas an MPR of 0.5 indicates that a patient has taken half of the medication needed to ensure continuous use.Citation35 All studiesCitation19–Citation22 used similar definitions of MPR.

Medication persistence assessed the long-term continuation of medication as the interval between first and last prescription claims divided by the study periodCitation19,Citation22 or if a prescription was refilled within a given period (eg, allowing a grace period between supply ending and refilling prescription).Citation21

Refill adherence assessed the proportion of patients remaining on treatment by the number of prescription refills during the study period.Citation19,Citation22 Satisfactory refill adherence was defined as dispensed refills covering 80%–120% of the prescribed treatment time. Refill adherence levels below 80% were referred to as undersupply and those over 120% as oversupply.Citation36,Citation37

Results by endpoint

The results are presented for adherence endpoints used in multiple studies, and data were pooled where feasible. The individual study results are presented in .

MEMS

MEMS was included as an outcome measure in three studies of schizophreniaCitation16–Citation18 and one study of epilepsy.Citation15 One study in schizophreniaCitation18 performed statistical analyses, but did not control for confounders, while another study in schizophreniaCitation17 performed statistical analyses and found that gender and random versus nonrandom design were effect modifiers. The third schizophrenia studyCitation16 performed two separate multivariate analyses to control for the overlapping influence of various predictors on adherence. A linear regression analysis showed that, when adjusting for the variability of other explanatory variables (confounders), only the Positive and Negative Symptom Scale total score and dosing complexity remained as significant predictors of adherence. A discriminant function analysis found that Positive and Negative Symptom Scale total score, dosing complexity, and duration of illness were variables with significant discriminant weights.Citation16

Although two schizophrenia studiesCitation17,Citation18 had similar study designs and patient populations, they reported adherence values of 66.2%Citation18 and 26%.Citation17 This difference might be explained by the fact that the group in which adherence was 26%Citation17 was based on a sample of only three patientsCitation17 and therefore the results may not be reliable. In the third schizophrenia study using MEMS with a commonly used threshold for adherence of 80%, 48% of patients were considered adherent.Citation16 Despite study differences, the findings for once-daily versus multiple daily dosing regimens were consistent, in that the dosing regimen was a strong predictor of adherence, meaning that patients on once-daily regimens had better adherence than those on twice-daily regimens.

The mean adherence rate per patient was also reported in one studyCitation16 because the authors questioned the validity of using a cutoff of 80% for adherence. The mean adherence rate using MEMS was 66.12% ± 31.00%. Dosing complexity was again a significant predictor of adherence as measured by MEMS.Citation16 The epilepsy study reported adherence outcomes at 4.5 months follow-up and found similar trends, ie, 87% (once-daily dosing) versus 81% (twice-daily dosing) versus 77% (three times daily) and versus 39% (four times daily,Citation15P < 0.05). In all studies using MEMS as an outcome measure, there was a consistent trend showing higher adherence rates with less frequent dosing regimens, irrespective of the study duration or disease. The small patient numbers and lack of data did not allow more detailed analyses.

Medication possession ratio

MPR was included as an outcome measure in three studies for depressionCitation19,Citation21,Citation22 (of which one study included a broader population of any patient receiving bupropion XL or SR)Citation21 and one study for schizophrenia.Citation20 Data from depression studiesCitation19,Citation22 were pooled because these were comparable in terms of study design, population, and outcomes. Both studies reported MPR values of around 50% for once-daily versus 35% for twice-daily dosing, implying an unadjusted OR of 2.01Citation19 and 1.78,Citation22 and therefore concluded that patients receiving once-daily medication were significantly more likely to remain on their medication than those receiving twice-daily medication. Both papers concluded that there were no differences in adherence level for different genders, while age and index date were effect modifiers.

The pooled OR was 1.89 (95% CrL 1.71–2.09, ) using a fixed-effects model. This meant that the odds of being adherent was 89% higher for patients on a once-daily versus twice-daily regimen. The third depression study, which included a broader mix of patients, found lower MPR values but a greater adherence rate for once-daily versus twice-daily regimens.Citation21 A similar conclusion was reached by Stang et al,Citation21 where effect modifiers were gender, having insurance, having authorized refills, remaining in the current prescription, having a repeat refill for the current prescription, and having a large number of total days of supply in the past year.

Table 4 Pooled results for adherence by medication possession ratio: odds ratios (95% CrL) of once-daily versus twice-daily regimens

The schizophrenia study found higher MPR values for stable patients on any dosing regimen. MPR adherence significantly improved for patients who decreased to once-daily dosing, and worsened for patients who increased from once-daily to multiple daily dosing compared with their stable counterparts.Citation20 The study concluded that for patients on stable dosing frequencies, the MPR before the dose change, and the demographic and clinical characteristics described previously, had little influence on the adherence rates.Citation20

Persistence

Studies assessing medication persistence included twoCitation19,Citation22 studies in depression and oneCitation21 in a broader population on bupropion XL or SR. In a retrospective database analysis, once-daily bupropion was associated with an average additional 44 days on therapy over the 9-month follow-up period, and an additional 28% of patients being adherent.Citation19 Both studies in depressionCitation19,Citation22 reported a significant difference in persistence results for once-daily (around 50%) versus twice-daily (30%) dosing. Both papers concluded that there were no differences in adherence levels for different genders, while age and index date were effect modifiers.Citation19,Citation22

The studyCitation21 identified effect modifiers as gender, having insurance, having authorized refills, remaining in the current prescription, having a repeat refill for the current prescription, and having a great number of total days of supply in the past year.Citation21

All three studiesCitation19,Citation21,Citation22 imply a similar calculated persistence OR for once-daily versus twice-daily dosing (OR 2.13, 95% CrL 1.78–2.53;Citation19 OR 2.07, 95% CrL 1.75–2.45;Citation22 and OR 2.07, 95% CrL: not applicable).Citation21 By pooling the results for the two depression studies,Citation19,Citation22 an OR of 2.10 (95% CrL 1.86–2.37) was estimated. This means that the odds of patients on once-daily regimen being adherent was more than twice the odds of patients being adherent on twice-daily dosing.

Refill adherence

Studies assessing refill adherence included two studies in depressionCitation19,Citation22 and one in a broader populationCitation21 on bupropion XL or SR. All three studies assessed the proportions with at least one refill during the study period, two studies assessed the proportion of at least six refills,Citation19,Citation21 and one study assessed the proportion of at least five refills,Citation22 and study periods ranged from 9 months to one year. For the studies of 9 months’ duration, the proportion of patients with at least one refill was 65%–75% on once-dailyCitation19,Citation22 versus around 56% on twice-dailyCitation19,Citation22 dosing. For the one-year mixed population study, around 60% on once-daily versus 51% on twice-daily regimens had at least one refill (P < 0.0001).Citation21 This study with a mix of populationsCitation21 found a similar trend of calculated refill adherence with QD (39%) versus BID (24%) regimens. Because adherence is expected to decrease over time, the studies assessed the proportions of patients with multiple refills during the study period. The proportion of patients with at least 5–6 refills was around 26%–31% for once-dailyCitation19,Citation22 versus 14%–19% for twice-dailyCitation19,Citation22 regimens over 9 months, and was 25% for once-dailyCitation21 versus 10% for twice-dailyCitation21 regimens over one year. The studies in patients with depression only conclude that there were no differences in adherence levels for the different genders, while age and index date were effect modifiers.Citation19,Citation22 A similar conclusion was reached by Stang et al,Citation21 where effect modifiers were gender, having insurance, having authorized refills, remaining in the current prescription, having a repeat refill for the current prescription, and having a great number of total days of supply in the past year.

Other measures of adherence

In addition to the four measures of adherence above, there were five studies that used other adherence measures, ie, pill count,Citation15,Citation16 MAQ,Citation34 CRS,Citation34 mean drug plasma levels,Citation32 and odds of missing a dose.Citation33 It was not possible to compare outcomes across these studies; however, the overall conclusions about dosing frequency and adherence per study are described below.

A prospective study in 52 patients with schizophreniaCitation16 used pill count to assess adherence levels in patients on once-daily versus multiple daily dosing. When adherence was treated as a dichotomous variable using a threshold of 80%, the adherence rate based on pill count was 76%. When adherence was treated as a continuous variable, the mean value for pill count was 85.45% ± 16.09%. Another prospective study in 26 patients with epilepsyCitation15 also used pill count to assess adherence levels in patients on once-daily versus multiple daily dosing. Both studiesCitation15,Citation16 found that adherence levels were higher in patients on less frequent dosing.

A survey study in 409 patients with schizophreniaCitation34 used MAQ to assess adherence levels in patients on once-daily versus multiple daily dosing. MAQ is a self-report that consists of four “yes/no” questions referring to the medication-taking behavior of the patient. The mean MAQ sum score was 2.97 ± 1.21, and 47.2% of patients showed good adherence in the sense of their MAQ sum score equaling four. Contrary to all other studies, the adherence levels were lower in patients on less frequent dosing. In fact, the higher the daily dosing frequency, the better the adherence, as rated with the MAQ. The authors explained that one of the possible reasons is that patients benefit from strictly structured daily life. In this perspective, a daily routine of taking the medication at set time points might be helpful to enhance patient adherence by reducing the likelihood of forgetting to take the prescribed drugs. An alternative explanation might have been that attending psychiatrists prescribed high daily dose frequency only to their reliable (ie, adherent) patients.

A study in schizophreniaCitation16 that compared adherence measures found that the capacity of clinicians to predict adherence was limited, with 42% of the subjects they identified as compliant being noncompliant based on MEMS results. Conversely, 44% of the group they identified as nonadherent was actually adherent according to MEMS data. Factors consistently associated with nonadherence included more severe symptomatology and increased dosing complexity, which is consistent with previous studies.

A retrospective study in epilepsyCitation32 with 49 patients used mean drug plasma levels to assess adherence levels in patients on once-daily versus multiple daily dosing (twice, three and four times daily) and in patients on twice-daily versus multiple daily dosing. Adherence rates were higher in patients taking diphenylhydantoin twice daily versus multiple times daily (three and four times daily, P < 0.001). Paired t-statistics indicated that the statistical difference was significant in patients on diphenylhydantoin. A similar difference was found between the plasma levels for phenobarbital obtained between once-daily and multiple daily dosing (twice, three and four times daily, P < 0.001). Therefore, adherence levels were higher in patients on less frequent dosing.

Another study of 670 patients in epilepsyCitation33 used odds of missing a dose to assess adherence levels in patients on once-daily versus multiple daily dosing. Each increase in dose frequency increased the odds of missing a dose, which in turn led to an increase in the number of seizures. Results showed that each increase in dose frequency increased the likelihood of a seizure after a missed dose by 36%. The study found that only number of years taking seizure medication was significantly associated with the likelihood of missing a dose.

Discussion

Twelve studies on the impact of dosing frequency on adherence in epilepsy, schizophrenia, or depression were identified. Five studies each used a different measure of adherence (ie, pill count,Citation15,Citation16 MAQ,Citation34 CRS,Citation34 odds of missing a dose,Citation33 and mean drug plasma levels)Citation32 so it was not possible to compare outcomes across these studies. Eight studies used common outcome measures, including MEMS,Citation15–Citation18 MPR,Citation19–Citation22 persistenceCitation19,Citation21,Citation22 or refill adherence.Citation19,Citation21,Citation22 Half of these were small prospective studies of short duration using MEMS and half were large retrospective US database analyses of up to one year in duration using MPR with or without persistence and refill adherence measures. Four studies did not control for confounders in their analyses.Citation15,Citation18,Citation31,Citation32 Due to differences in study design, patient populations, and outcomes, it was not possible to pool results together with confdence. However, the findings from individual studies and from pooled results show that adherence is improved with once-daily dosing compared with more frequent daily dosing, regardless of the adherence measure used.

The results in depression studies enabled us to pool them together. When pooling the results together for the two depression studies that used persistence as a measure of adherence,Citation19,Citation22 an OR of 2.10 (95% CrL 1.86–2.37) was estimated. This means that the odds of patients on a once-daily regimen being adherent was more than twice the odds of being adherent for patients on twice-daily dosing. Our study confirmed these results also through pooling of results of depression studiesCitation19,Citation22 when MPR was used as a measure of adherence. The pooled OR for these two depression studiesCitation19,Citation22 was 1.89 (95% CrL 1.71–2.09), meaning that patients on once-daily dosing were 89% more adherent than patients on twice-daily dosing. The differences in adherence measures (ie, MEMS, change in MPR) across the schizophrenia and epilepsy studies alone were too large to allow pooling of results.

The major strength of this study is that, to the authors’ knowledge, it is the first on this important topic. No other systematic review was identified in schizophrenia, epilepsy, and depression on dosing frequency and adherence. A second strength of this systematic literature review is that its findings are in line with results from other therapeutic areas. A trend of better adherence with less frequent dosing was also found in review of chronic diseases with asymptomatic periods.Citation35 The review of chronic diseases with asymptomatic periodsCitation35 could not perform statistical analyses of results or pool them together because of differences in study design, inclusion and exclusion criteria, different methods, and patient populations. Our review was able to pool data from some studies, although differences in populations, design, and measures of adherence made it difficult to combine all results identified.

A limitation of this review was that there were relatively few relevant studies identified, with small numbers of patients and short follow-up periods in some studies. Therefore, no clear conclusions about dosing frequency and adherence could be drawn in specific diseases (especially in epilepsy) or by duration of treatment. A second limitation was the lack of consensus on adherence measures and their interpretation across studies, which limits the scope for comparisons in general and the pooling of quantitative adherence data in particular. Moreover, although some adherence measures used, based on recorded bottle openings or prescription refill data, offer a more objective measure of adherence than self-reports, a bottle opening does not guarantee that the patient took the dose or the correct dose. Finally, adherence levels depend on study duration and the cutoff used for defining an adherent patient.

Further research that assesses the direct link between dosing regimen (controlling for confounding factors) and health outcomes (eg, relapse rates) through the mechanism of nonadherence would be valuable. Current studies assess either the link between dosing regimen and adherence, as in this review, or the relationship between nonadherence and health outcomes. Assessing the link between dosing frequency and hard endpoints in one study could be of interest to prescribers as well as health care policy-makers. Future studies that wish to allow for comparisons between studies, based on objective adherence measures, should consider using a common duration and cutoff definition.

All reviewed studies reached a similar conclusion, ie, that a simplified dosing regimen leads to improved adherence, regardless of the measure of outcome used, with the exception of the study by Meier et al.Citation34 In that study, MAQ was used as a measure of adherence which, in contrast with the other studies, reported that daily dose frequency was positively correlated with better patient adherence. One of the possible explanations is that patients benefit from a strictly structured daily life.Citation34 An alternative explanation might be that attending psychiatrists prescribe high daily dose frequency only to their more reliable (ie, adherent) patients.Citation34

Nonadherence has a negative impact on patients’ symptoms which can result in relapses and put an additional burden on health care resources. This costly problem that faces patients, health care providers and payers is increasingly recognized. While many factors are known to affect adherence, improving disease management by simplifying dosing regimens is one means to this end. This systematic review and meta-analysis suggests that there is an opportunity to improve outcomes for patients with chronic psychiatric diseases effectively by simplifying dosing regimens.

Disclosure

Funding and support was provided by AstraZeneca to MAPI Consultancy for the independent systemic review and meta-analysis of the dosing frequency and adherence in chronic psychiatric disease. Medical writing, editorial, and technical support services were provided by Goran Medic of MAPI Consultancy. Goran Medic did not receive any other form of compensation from Astra Zeneca and is fully employed by MAPI Consultancy. TD and OG are former employees of AstraZeneca. The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- WuEQBirnbaumHGShiLThe economic burden of schizophrenia in the United States in 2002J Clin Psychiatry2005661122112916187769

- HovingaCAAsatoMRManjunathRAssociation of non-adherence to antiepileptic drugs and seizures, quality of life, and productivity: survey of patients with epilepsy and physiciansEpilepsy Behav20081331632218472303

- BakerGAJacobyABuckDQuality of life of people with epilepsy: a European studyEpilepsia1997383533629070599

- AndradeLCaraveo-AnduagaJJBerglundPThe epidemiology of major depressive episodes: results from the International Consortium of Psychiatric Epidemiology (ICPE) SurveysInt J Methods Psychiatr Res20031232112830306

- KesslerRCBerglundPDemlerOThe epidemiology of major depressive disorder: results from the National Comorbidity Survey Replication (NCS-R)JAMA20032893095310512813115

- CramerJARoyABurrellAMedication compliance and persistence: terminology and definitionsValue Health200811444718237359

- KelinKLambertTJrBrnabicAJTreatment discontinuation and clinical outcomes in the 1-year naturalistic treatment of patients with schizophrenia at risk of treatment nonadherencePatient Prefer Adherence2011521322221660103

- LlorcaPMPartial compliance in schizophrenia and the impact on patient outcomesPsychiatry Res200816123524718849080

- ChenEYHuiCLDunnELA prospective 3-year longitudinal study of cognitive predictors of relapse in first-episode schizophrenic patientsSchizophr Res2005779910416005389

- EatockJBakerGAManaging patient adherence and quality of life in epilepsyNeuropsychiatr Dis Treat2007311713119300542

- DavisKLCandrilliSDEdinHMPrevalence and cost of nonadherence with antiepileptic drugs in an adult managed care populationEpilepsia20084944645418031549

- EttingerABManjunathRCandrilliSDPrevalence and cost of nonadherence to antiepileptic drugs in elderly patients with epilepsyEpilepsy Behav20091432432919028602

- FaughtEDuhMSWeinerJRNonadherence to antiepileptic drugs and increased mortality: findings from the RANSOM studyNeurology2008711572157818565827

- LiuXChenYFariesDEAdherence and persistence with branded antidepressants and generic SSRIs among managed care patients with major depressive disorderClinicoecon Outcomes Res20113637221935334

- CramerJAMattsonRHPreveyMLHow often is medication taken as prescribed? A novel assessment techniqueJAMA1989261327332772716163

- RemingtonGKwonJCollinsAThe use of electronic monitoring (MEMS) to evaluate antipsychotic compliance in outpatients with schizophreniaSchizophr Res20079022923717208414

- DiazENeuseESullivanMCAdherence to conventional and atypical antipsychotics after hospital dischargeJ Clin Psychiatry20046535436015096075

- ByerlyMFisherRWhatleyKA comparison of electronic monitoring vs clinician rating of antipsychotic adherence in outpatients with schizophreniaPsychiatry Res200513312913315740989

- McLaughlinTHogueSLStangPEOnce-daily bupropion associated with improved patient adherence compared with twice-daily bupropion in treatment of depressionAm J Ther20071422122517414593

- PfeifferPNGanoczyDValensteinMDosing frequency and adherence to antipsychotic medicationsPsychiatr Serv2008591207121018832509

- StangPYoungSHogueSBetter patient persistence with once-daily bupropion compared with twice-daily bupropionAm J Ther200714202417303971

- StangPSuppapanayaNHogueSLPersistence with once-daily versus twice-daily bupropion for the treatment of depression in a large managed-care populationAm J Ther20071424124617515697

- BiesRRGastonguayMRColeyKCEvaluating the consistency of pharmacotherapy exposure by use of state-of-the-art techniquesAm J Geriatr Psychiatry20021069670512427578

- de KlerkEPatient compliance with enteric-coated weekly fuoxetine during continuation treatment of major depressive disorderJ Clin Psychiatry200162434711599648

- LeopoldNAPolanskyMHurkaMRDrug adherence in Parkinson’s diseaseMov Disord20041951351715133814

- BovaCAFennieKPKnafGJUse of electronic monitoring devices to measure antiretroviral adherence: practical considerationsAIDS Behav2005910311015812617

- McKenneyJMMunroeWPWrightJTJrImpact of an electronic medication compliance aid on long-term blood pressure controlJ Clin Pharmacol1992322772831564133

- ShemeshENon-adherence to medications following pediatric liver transplantationPediatr Transplant2004860060515598333

- HigginsJPTGreenSCochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of InterventionsVersion 5.1.0 2011 Available from: http://www.cochrane-handbook.org/Accessed November 23, 2011

- NICE Decision Support Unit Available from: http://www.nicedsu.org.uk/Technical-Support-Documents(1985314).htmAccessed November 23, 2011

- DoughtyJBakerGAJacobyACompliance and satisfaction with switching from an immediate-release to sustained-release formulation of valproate in people with epilepsyEpilepsy Behav2003471071614698705

- ZaccaraGGalliAEffectiveness of simplified dosage schedules on the management of ambulant epileptic patientsEur Neurol197918341344527610

- CramerJAGlassmanMRienziVThe relationship between poor medication compliance and seizuresEpilepsy Behav2002333834212609331

- MeierJBeckerTPatelAEffect of medication-related factors on adherence in people with schizophrenia: a European multi-centre studyEpidemiol Psichiatr Soc20101925125921261221

- SainiSDSchoenfeldPKaulbackKEffect of medication dosing frequency on adherence in chronic diseasesAm J Manag Care200915e22e3319514806

- AnderssonKMelanderASvenssonCRepeat prescriptions: refill adherence in relation to patient and prescriber characteristics, reimbursement level and type of medicationEur J Public Health20051562162616126746

- KrigsmanKMelanderACarlstenARefill non-adherence to repeat prescriptions leads to treatment gaps or to high extra costsPharm World Sci200729192417268941