Abstract

Serotonin is a widely investigated neurotransmitter in several psychopathologies, including suicidal behavior (SB); however, its role extends to several physiological functions involving the nervous system, as well as the gastrointestinal and cardiovascular systems. This review summarizes recent research into ten serotonergic genes related to SB. These genes – TPH1, TPH2, SLC6A4, SLC18A2, HTR1A, HTR1B, HTR2A, DDC, MAOA, and MAOB – encode proteins that are vital to serotonergic function: tryptophan hydroxylase; the serotonin transporter 5-HTT; the vesicular transporter VMAT2; the HTR1A, HTR1B, and HTR2A receptors; the L-amino acid decarboxylase; and the monoamine oxidases. This review employed a systematic search strategy and a narrative research methodology to disseminate the current literature investigating the link between SB and serotonin.

Introduction

The serotonergic system has been studied extensively since the discovery of serotonin in the early 1950s. The isolation of the serum vasoconstrictor, 5-hydroxytryptamine (5-HT), from beef serum was first reported in 1948.Citation1 This factor released from platelets during blood clotting was aptly named “serotonin,” as a result of its tonic effect on smooth muscle contraction in serum.Citation1 Subsequently, colorimetric assays determined that this compound was identical to enteramine, another indole substance identified two decades earlier in preparations from enterochromaffin cells (ECs) of the gastrointestinal (GI) tract.Citation2 One year later, Twarog and PageCitation3 demonstrated the presence of serotonin in the mammalian brain. Along with the previous two locations, the high concentration of serotonin in the brainstem and its moderate distribution throughout the entire mammalian brain sparked interest in the role of serotonin as a neurotransmitter. The three experimental sites of serotonin emphasized the possible roles for serotonergic signaling in intestinal motility, platelet aggregation, and neurotransmission. As a result of these initial findings, research into the precise role of serotonin in human physiology exploded. Of particular interest to the research community is the role serotonin plays as a mediating factor in psychiatric disorders.

Human behavior is governed by a complex interplay of genetic and environmental factors, which may work in concordance to increase the incidence of specific psychiatric behaviors.Citation4 One such behavior, suicidal behavior (SB), has been the subject of much etiological research. This investigation seeks to understand the role of serotonergic genetics in the context of SB by summarizing the recent research on the possible associations between SB and polymorphisms of genes that encode key proteins in the serotonergic system.

Objectives

The purpose of this study is to perform a thorough narrative review to investigate the serotonergic genetic determinants and their association with SB. For the purpose of this review, we will determine the association of ten genes involved in different aspects of the serotonergic system.

This review summarizes research into polymorphisms (genetic variants) of ten serotonergic genes in relation to SB. These genes – TPH1, TPH2, SLC6A4, SLC18A2, HTR1A, HTR1B, HTR2A, DDC, MAOA, and MAOB – encode proteins vital to serotonergic function: tryptophan hydroxylase (TPH); the serotonin transporter 5-HTT; the vesicular transporter VMAT2; the HTR1A, HTR1B, and HTR2A receptors; the L-amino acid decarboxylase (AAAD); and the monoamine oxidases (MAOs). Before discussing the methodology and results of this narrative review, we will first provide a thorough background on both the serotonergic system and SB.

After outlining both the background and systematic search strategy, this review seeks to provide a comprehensive overview on the available literature evaluating the role of serotonergic genes in SB, doing so through an evaluation of all serotonergic system components and their associated genetic polymorphisms separately.

See for the genes and specific single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) related to SB that have been selected for this review. The objectives of the review are to:

Table 1 Summary of ten serotonergic genes and associated mutations

Determine the genes and polymorphisms that have been studied in relation to both serotonin and SB.

Determine whether or not there is an association between the genes involved in serotonergic synthesis or processing and SB.

Evaluate where the gaps in the current literature are in an effort to determine the important questions that need be answered in future research.

Background

The serotonergic system

Almost all of the serotonin in the blood is stored within intracellular platelet vesicles, and initially, platelet aggregation was deemed to be its primary role within the blood.Citation5 However, over the past 60 years, the various roles for serotonin in maintaining cardiovascular homeostasis have since expanded to monitoring vascular tone, abnormalities in cerebrovascular function, and normal cardiac functions (such as heart rate, contractility, and cardiac output).Citation5 At the platelet level, experiments with TPH1-deficient mice have indicated that serotonin release increases platelet adhesiveness, aggregation, and thrombosis development.Citation5,Citation6 Vascular tone is partially controlled by the activation of serotonin receptors (5-HTR) in the vascular endothelial and smooth muscle cells.Citation7,Citation8 Serotonin has either a contractile or dilatory function based on the receptor subtype and site of action.Citation7 In terms of cardiac function, serotonin interacts with the 5-HT4 receptor on cardiac myocytes, thereby having positive chronotropic, inotropic, and lusitropic effects that may mediate atrial rate and rhythmicity.Citation5,Citation9 The majority of ectopic serotonin is created in the GI system.Citation10 Serotonin is produced in the bowel by ECs and by enteric neurons at the myentric plexus.Citation10 It is derived from the amino acid, tryptophan (TRP), and requires inactivation in order to cross membrane barriers.Citation10 A large concentration of serotonin is released into the submucosa due to the relatively large distance between the basolateral membrane of ECs and the neuron.Citation10 The precise action of serotonin in the gut is dependent on the expression of various subtypes of 5-HTR.Citation11–Citation16 For instance, Bulbring and CremaCitation17 postulated that serotonin stimulates intrinsic neurons to initiate peristaltic movement and secretory reflexes. In addition, serotonin release elicits the sensation of nausea and discomfort through the central nervous system (CNS) via primary afferent neurons.Citation10 Altogether, serotonin plays an intimate role within the GI tract by transmitting signals within the enteric neurons and CNS.

The most frequently studied function of serotonin is within the brain and CNS. CNS production of serotonin occurs primarily in the raphe nucleus, a group of serotonergic neurons located in the posterior region of the pons.Citation18 These neurons are believed to project into areas of the CNS that contain 5-HTR, including the cerebral cortex, cerebellum, suprachiasmatic nucleus, ventrolateral geniculate body, amygdala, and hippocampus, amongst others.Citation19 A large number of 5-HTR subtypes are distributed widely throughout the brain and CNS.Citation19 As a result, serotonergic transmission is believed to mediate a variety of physiological functions including temperature regulation, mood, anxiety, emesis, sleep, appetite, blood pressure, and the perception of pain.Citation19 Pharmacologic interventions of the serotonergic system play an important role as first-line medications for the management of depression, and are also used in cases of anxiety disorder, obsessive-compulsive disorder, and eating disorders.Citation20 The strong correlation between emotion, behavior, and serotonergic transmission provides a basis for investigating serotonin in relation to a variety of psychological impairments and psychiatric disorders and, more specifically, suicide.

Suicidal behavior

Suicide is not only a devastating event to the close network of friends and family of the deceased; it is a phenomenon that seriously disrupts the wider society it occurs within. Suicide has a significant impact on the world’s population, as close to 1 million people die from suicide every year.Citation21 One should note that the prevalence of suicide varies among different age groups. For individuals aged 15–44 years, suicide ranks as one of the top three leading causes of death.Citation21

Often less documented when discussing suicide is the issue of attempted suicide; the World Health Organization notes that the rate of attempted suicide is 20 times greater than that of suicide mortality.Citation21 As stated earlier, the ill effects of suicide extend beyond those individuals who are directly affected. Families, communities, and whole societies may be weakened by emotional and economic losses. In 2004, for example, suicide and intentional injuries accounted for an approximate loss of $3.3 billion, which was 17% of injury costs for the Canadian economy.Citation22

The psychiatric assessment for evaluating SB can be quite complex and variable. Suicidal attempt, defined most commonly as a self-directed injurious act with some intent to end one’s own life, resides on a continuum of SB that commences with suicidal ideation and ends with suicide completion.Citation23 Clinically, suicidal ideation is classified according to the American Psychiatric Association Guidelines as “thoughts of serving as the agent of one’s own death”, whereas suicidal intent is described as “subjective expectation and desire for a self-destructive act to end in death.”Citation24 The distinction between these two definitions, although diagnostically important, may be clinically difficult to attain based on the varying depth of information obtained upon patient evaluation and the established relationship with the patient. In addition, very few studies recognize a difference between ideation and intent. This clinically relevant distinction may increase the predictive value in subsequent studies which, up to this point, have shown limited predictive value based on the 100-fold lower prevalence of suicide attempts compared to suicidal ideation.Citation24 Furthermore, researchers have attempted to design assessment scales to provide an objective measure of SB for use in genetic and proteomic association studies (see FowlerCitation25 for examples). However, these suicide assessment scales provide insufficient predictive validity for future suicide attempts. They are limited by the willingness of some patient to share information, the ability of a clinician to properly and consistently develop an assessment, and their limited positive predictive value and high rate of false positives.Citation25 Despite the current limitations in connecting clinical and research assessments, the importance of using research to establish broad and predictive risk factors for SB is paramount.

The established link between mood disorders and SB has been reported extensively over the past 40 years. Initially in 1970, Guze and RobinsCitation26 reported a significant link between bipolar affective disorder and suicide completions. Subsequent studies supported the associated risk between bipolar disorder and SB and, in 1989, additional evidence of a link between various psychiatric disorders and adolescent suicide risk was published.Citation27 Major depression, adjustment disorder, dysthymia, schizophrenia, and borderline personality disorder all exhibited a prevalence of at least 14% in a group of suicide victims.Citation27 In 1996, Beautrais et alCitation28 demonstrated that those patients who made serious suicide attempts also had high rates of mood disorders, substance use disorders, conduct disorder, or antisocial personality disorder, and nonaffective psychosis. Since then, multiple studies have linked suicide attempts to anxiety disorder, bipolar disorder, and obsessive-compulsive personality disorder.Citation29–Citation31 As a result, research into the psychobiology of psychiatric disorders and SB has increased substantially over the past two decades. In 2003, MannCitation23 proposed a stress diathesis model of suicidality, which explained that SB could result from a complex combination of genetic and environmental factors. Environmental factors have been largely implicated in the influence of suicidal ideation.Citation32 One study by PaykelCitation33 illustrated how environmental factors such as adversity during childhood, employment stress, acute/chronic stress, inadequate social support, loss/separation, and family adversity can influence an increase in the incidence of suicidal behavior or major depression.

SB is defined in this review as self-injurious actions with the intent to end life. Like many psychiatric disorders, SB is complex in etiology. Propensity for SB is mitigated by a multitude of risk factors including the presence of co-occurring psychiatric disorders, social stresses such as a history of abuse, minimal access to mental health services, increased access to methods for attempting suicide, and complex gene–environment interactions.Citation34 Several lines of evidence inform our current understanding of SB. Research into the genetic component of SB is supported by family and twin studies. These studies have noted a high rate of SB in the relatives of individuals with a history of attempted or completed suicide.Citation35–Citation38 Subsequent adoption studies, which investigated children who have been adopted, have provided evidence that the influence of social factors alone cannot account for SB.Citation39 Such results may suggest that heritable factors play a key part in mediating SB risk.

Establishing a link between serotonin and suicidal behavior

Many studies have provided evidence of a strong link between depression and SB, and research into the biochemical foundation of mood disorders has fuelled a number of studies that link the serotonergic system to suicidality.Citation40 Serotonin is a monoamine neurotransmitter that is synthesized from the hydroxylation of TRP by the enzymes TPH1 and TPH2.Citation19 In the process of neurotransmission, vesicles of the presynaptic neuron release serotonin into the synaptic cleft due to an increase in intracellular calcium concentration.Citation19 Free serotonin binds to receptors on the postsynaptic neuron to illicit downstream intracellular signaling events that ultimately lead to its metabolism into 5-hydroxyindoleacetic acid (5-HIAA) by the enzyme, MAOA.Citation19 A serotonin transporter (5HTT) resides in the presynaptic membrane allowing reuptake of excess hormone from the synaptic cleft.Citation19 Serotonin receptors on the pre-synaptic neuron are also capable of binding serotonin in the synapse and inhibiting further neurotransmitter release.Citation19 Stemming from two initial studies in the early 1980s by Stanley and Mann, as well as by Stanley et al,Citation41–Citation43 alterations in the serotonergic system have been extensively implicated in the psychopathology of SB. These initial studies identified a difference in the quantity of 5-HTR in the pre- and postsynaptic membranes of the frontal cortex of suicide victims.Citation42,Citation43 Most of the studies that have followed can be grouped into three broader categories involving protein/receptor, genetic/polymorphic, and hormone/metabolite differences. All of these components may play a role in altering the impulsivity and response to stressors in the minds of suicidal individuals. While some studies have investigated the role of TRP depletion and suicidal ideation, many have shown no association.Citation44 However, some studies have shown that TRP depletion increases self-aggressive behavior.Citation45 A new area of research in the field of serotonergic pathways associated with suicidal behavior includes the exploration of inflammatory processes related to serotonin processing. Kynurenine (KYN) is formed from its precursor, TRP, if KYN levels are associated with TRP concentrations, these KYN pathways are argued to have the ability to influence levels of the TRP metabolite serotonin. The cytokine-stimulated production of KYN from TRP is an inflammatory process that has been investigated among suicide attempters and other individuals with a history of psychiatric illness, where KYN production was higher among individuals with a history of suicide attempts.Citation46

Drug-induced alterations in serotonergic signaling

A variety of pharmacological agents target the serotonergic system for use as antiemetics, and in mood disorders as antidepressants and anxiolytics.Citation47,Citation48 During the past 10 years, concerns have developed that medications interfering with serotonergic system function may precipitate SB in susceptible patients.Citation49 Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) are the most extensively used in the treatment of depression, and they are studied in relation to their influence on SB. These medications are used to block the reuptake of serotonin into the presynaptic neuron by selectively inhibiting 5HTT. Initially, the US Food and Drug Administration reported a risk of suicidal effect of antidepressants in a retrospective review in pediatric patients.Citation49 In 2005, a retrospective, pooled analysis of over 40,000 individuals from the UK Medicines and Healthcare Products Regulatory Agency database of randomized control trials reported 177 episodes of suicidal ideation, 172 episodes of nonfatal self-harm, and 16 suicides.Citation50 In all, there was no evidence of a significant associated risk of suicide with SSRIs in adults.Citation50 More recently, a Cochrane review by Hetrick et alCitation51 provided evidence of an increased risk for suicide-related activity in adolescents on antidepressants (relative risk of 1.58; confidence interval [CI] =1.02–2.45) compared to controls. Other psychopharmacological drugs have shown a protective effect on suicidal risk. Lithium, for instance, enhances serotonin release and may reduce suicidal risk by limiting impulsive and aggressive behavior.Citation52 As a result of these studies, clinicians are advised to provide information to patients and family on the efficacy and safety of antidepressant medication for depression.Citation51

It is difficult to hypothesize the mechanisms by which SSRIs may increase suicidal risk in a specific age group while keeping the previously discussed relationship between the serotonergic system and SB, as well as the existing psychopathology for which these SSRIs were prescribed, in mind. The issue of methodological quality remains a challenge to analyzing the effects of antidepressants on SB risk. The ethical and long observational periods required to perform adequate assessments are two major barriers to experimental design.Citation53 The majority of the experimental studies conducted thus far have taken data retrospectively from clinical trials and not analyzed longitudinal datasets with placebo effects, for obvious ethical reasons. Contrary to experimental retrospective studies, some observational studies in several large populations and countries have shown a relative decrease in fatal and nonfatal suicide attempts with greater use of antidepressants.Citation54,Citation55 With the relatively new implication of suicidal risk with short-term antidepressant usage, future studies should aim to uncover more data regarding the long-term and short-term implications of antidepressants in various at-risk suicidal populations.

In an effort to adequately evaluate how genetic factors may mediate a relationship between the serotonergic system and SB, a systematic search strategy was employed to identify genes relevant to this investigation. The findings of this search are summarized in a narrative manner in the sections to follow.

Methodology

This investigation employed a systematic process for searching predefined databases with the intent of acquiring related literature to investigate the topic. No date restrictions were placed on the search strategy, which was performed from January–March 2012. The PubMed (National Center for Biotechnology Information, US National Library of Medicine, Bethesda, MD, USA), PsycINFO® (American Psychological Association, Washington, DC, USA), and Web of Knowledge® (Thomson Reuters, Philadelphia, PA, USA) databases were searched for articles with the key terms “(serotonin OR serotonin system) AND (suicide OR suicidal behavior)” and “(serotonergic genes OR serotonin genes) AND (suicide or suicidal behavior).” Articles were excluded if they were: 1) not in English; 2) not available electronically; or 3) had abstracts that suggested that the paper did not relate to the search terms. The resulting articles were then evaluated for content. This search strategy allowed for the identification of ten serotonergic genes – TPH1, TPH2, SLC6A4, SLC18A2, HTR1A, HTR1B, HTR2B, DDC, MAOA, and MAOB – which had been studied in the context of SB. With this information, a subsequent second search was conducted using the gene name or gene product as key search terms. In cases where >300 papers were retrieved, the terms “AND (polymorphism or mutation)” were added to the search criteria to improve the relevance of the search results. All searches were filtered using the described exclusion criteria. The resulting articles were then analyzed to construct a thematic overview of our current understanding of the role of serotonergic genes in SB.

Results

The results of the systematic search procedure described in the Methodology section are summarized in , where the gene, mutations, and studies supporting or refuting the association findings are presented. In addition, we have provided a second table () that outlines all of the studies ascertained for this review. In , we have outlined each included study, illustrating the genes, SNPs, ethnicities, number of participants, outcome definitions, and association findings. As described in the Methodology section, the studies investigating each genetic variant will be critiqued and discussed in organized sections by serotonergic system components in conjunction with the SNPs of interest.

Table 2 Summary of selected studies for narrative review

TPH (TPH1 and TPH2)

Many key proteins and metabolites involved in the neurotransmission of serotonin have been investigated in relation to the brains of suicidal victims (see Bach and ArangoCitation56 for an extensive review). The biochemical synthesis of serotonin in neurons of the raphe nucleus begins with the conversion of L-tryptophan into 5HT by the enzyme, TPH.Citation19 Two isoforms of this enzyme, TPH1 (tph1, 11p15.3–p14) and TPH2 (tph2, 12q21.1), are expressed in the CNS; however, TPH2 levels are 2.5-fold higher than TPH1.Citation57,Citation58

The TPH genes are among the most thoroughly studied of the SB candidate genes, with a number of well-characterized polymorphisms. Polymorphisms are changes in a deoxyribonucleic acid sequence (at an individual or population level). Distinct polymorphisms can arise in particular arrangements, which are termed haplotypes.Citation59 Two such polymorphisms are SNPs located in intron 7.Citation60 The two SNPs, consisting of A to C substitution at nucleotide 779 (A779C) and 218 (A218C) are found in strong linkage disequilibrium, where the two aforementioned genotypes at the two described loci are not independent of one another.Citation60 The A779C polymorphism’s location is known to be up the polypyrimidine stretch, which is upstream from the 3′ acceptor splice site, and this stretch additionally forms a known consensus sequence recognized by proteins when in pre-messenger ribonucleic acid (mRNA).Citation60 In addition, Nielsen et alCitation60 noted that the A218C site is found in a plausible GATA transcription factor binding site. These polymorphisms have not been found to alter splicing of the TPH pre-ribonucleic acid or influence TPH gene expression.Citation60

Studies examining possible associations between the A779C and A218C polymorphisms and SB have yielded conflicting results. A landmark study conducted by Nielsen et alCitation61 in 1994 reported a significant association between TPH genotype and SB in violent offenders (P=0.16).

However, subsequent studies utilizing samples from various ethnicities did not yield consistent results. Several studies failed to show an association between SB and A779C, suggesting that the polymorphism is not a major contributor to SB.Citation62–Citation65 While some studies show an association between A218C and SB, several have failed to show such an association.Citation47,Citation62,Citation63,Citation65–Citation67 A study conducted by Tsai et al,Citation68 found that the A218C genotype was significantly associated with SB in depressed patients (P=0.001). Another study performed by Rujescu et alCitation69 noted a weak yet significant increase in the frequency of the A218 allele (odds ratio [OR]: 1.33; 95% CI =1.17–1.50; P=0.00002) in Caucasian suicide attempters/victims (n=147) as compared to controls (n=326), providing evidence for an association between the A218 polymorphism and SB. A meta-analysis of nine studies examining the A218C polymorphism and SB performed by Bellivier et al,Citation70 revealed a significant association using the fixed effect method (OR =1.62; 95% CI =1.26; 2.07) and the random effect method (OR =1.61; 95% CI =1.11; 2.35). These results support the theory that the A allele has a dose-dependent effect on the presence of SB, where a homozygous AA genotype pool has a larger frequency of SB.Citation70 Some evidence has been offered to suggest reasons why variances continue to be shown between studies examining the association between these polymorphisms and SB. For example, Du et alCitation71 claimed that these variances are due to: largely different phenotypic baseline characteristics between study populations (some studies look at individuals who have engaged in suicide attempts, who had completed suicide, and individuals with vague descriptions of SB); different sample populations with varying comorbid psychiatric disorders; and the methodological fall-backs of case-control studies (differing sampling pools for cases and controls). After an extensive review of the current literature, one can begin to note that while there is evidence supporting the link between SB and the A218C or A779C polymorphisms, there is still contention among the research community and a lack of well-sampled participant data to provide evidence supporting the association between SB and the A218C or A779C polymorphisms across different ethnicities. As such, it is pertinent that further research be done to produce a stronger and more vivid picture of the phenomena under study.

To provide further insight into the need for future research, one should note the 1999 Rotondo et alCitation72 study in which they investigated two common SNPs in the TPH promoter region: the A6526G and G5806T polymorphisms. However, further research examining these two polymorphisms in the context of SB has not yielded conclusive results.Citation64 While some studies have found that certain haplotypes of these SNPs are more frequent among suicide cases as compared to controls, these results have not been replicated by studies sampling other populations.Citation64,Citation73 Koller et al,Citation64 for instance, did not find an association between the A6526G (χ2 =2.248; degrees of freedom [df] =2; P=0.325), G5806T (χ2 =1.477; df =2; P=0.478) or A779C (χ2 =0.813; df =2; P=0.666) polymorphisms and SB in alcohol dependent individuals (n=321). In addition, a study conducted by Turecki et al,Citation73 which compared the genotypes of suicide completers (n=101) to controls (n=129) found that the (–6526G –5806T 218C) haplotype was considerably more recurrent among suicide cases (χ2 =11.30; df =2; P=0.0008; OR =2.0, CI: 1.30–3.6). However, the study did not find any meaningful discrepancy in genetic variation at a single locus.Citation73 As such, more research is required to understand the influence of the A6526G and G5806T polymorphisms on SB. It is also necessary to examine the possible effects of ethnic variations in allele frequencies.

AAAD (DDC)

AAAD is the enzyme that converts 5-HTP to serotonin. Research investigating mutations associated with the gene coding for this enzyme concluded that abnormalities in the gene sequence for the enzyme AAAD can lead to a serious deficiency for both serotonin and catecholamines, often resulting in severe neurological dysfunction in infancy, which may be characterized by vegetative symptoms.Citation73 This enzyme is encoded by the dopa decarboxylase gene (DDC). The DDC gene is located on the short arm of chromosome 7 (7p12.1–p12.3).Citation75 Research into DDC gene polymorphisms in relation to SB has proved limited. While recent research has identified several mutations in DDC, many such mutations have yet to be characterized on a transcriptional or translational level.Citation74,Citation76 The DDC gene has been most commonly studied in relation to impulsive aggression and violence; few researchers have attempted to explore the DDC gene in relation to suicidal behavior. However, in 2007, Giegling et alCitation77 studied three gene variants in DDC (rs1451371, rs1470750, and rs998850) in a sample of German suicide attempters (n=167), Caucasian suicide attempters (n=92), and German control subjects (n=312). Among suicide attempters, rs1451371 and rs1470750 were found to be marginally associated with nonviolent suicide methods. More research is required to corroborate these findings.

VMAT2 (SLC18A2)

The vesicular transporter, VMAT2, shuttles serotonin into storage vesicles in the presynaptic neuron. The VMAT2 is encoded by the SLC18A2 gene, located on the long arm of chromosome 10 (10q25).Citation78,Citation79 A 2001 study conducted by Glatt et alCitation80 identified four relatively frequent polymorphisms. Two of these polymorphisms, located in exons 3 and 15, respectively, result in changes to the amino acid sequence (T82M and M53I). The other two, found in exons 3 and 5, are synonymous SNPs (T83G and C74T). A subsequent study by Burman et alCitation81 examined the biochemical properties of the VMAT2 receptors expressed the T68M, A183G, T249M, and M453I polymorphisms. Interestingly, the VMAT2 vesicular transporters possessing the T68M polymorphism were found to have slightly higher 3H-serotonin uptake than wild-type transporters.Citation81 In contrast, the M453I polymorphism was associated with slightly lower 3H-serotonin uptake as compared to wild type VMAT2 transporters.Citation81 Such results indicate that the M453I polymorphism significantly alters the apparent affinity of VMAT2 for serotonin. VMAT2 inhibition can lead to a depletion of 5-HT and other monoamines such as dopamine, noradrenaline, and histamine, and has been observed to cause a growth reduction in mice.Citation82 Although the relationship between these polymorphisms and SB has not yet been examined, such results have exciting implications for future studies into the effects that the M453I and T68M polymorphisms may have on SB treatment.

MAOA and MAOB (MAOA and MAOB)

MAOA and MAOB are enzymes responsible for metabolizing serotonin. In addition, these monoamine enzymes are often found in the outer mitochondrial membrane, where they are in charge of the degradation of biogenic amines.Citation83 It is important to note that these enzymes have important implications in the clinical setting. MAOA, the enzyme that metabolizes the conversion of serotonin into 5-hydroxyindole acetaldehyde, has also been investigated as a potential source for variances associated with SB and mood disorders. Two recent meta-analyses of the variable number of tandem repeats (VNTR) polymorphism of the MAOA enzyme in suicide victims reported no significant association with SB.Citation84,Citation85 Few genetic polymorphisms have been explored in relation to SB, and even fewer studies have examined the relationship between SB and MAOA concentration or activity. Although, Mann and Stanley demonstrated that MAOA activity in postmortem prefrontal cortex samples of suicide victims did not differ significantly from controls, there was significantly increased activity of MAOA in the hypothalamus of suicide victims in one study.Citation86,Citation87

Abnormal levels of these enzymes have been found in individuals with neuropsychiatric disorders such as bipolar disorder and X-linked intellectual disability.Citation88 These enzymes are encoded by two tightly linked genes that are arranged tail-to-tail on the short arm of the X chromosome between bands Xp11.23 and Xp21.2.Citation83,Citation88 Analysis has shown that these genes are 73% homologues and have identical intron–exon organization.Citation89 Research into polymorphisms of the MAOA and MAOB genes is limited. While polymorphisms in the two genes have been identified, little is known about their effects on a protein-level or in relation to SB.

Perhaps the only well-studied MAO polymorphism is a functional polymorphism in the promoter region of the MAOA gene. In 1998, Sabol et alCitation89 identified a polymorphism located 1.2 kb upstream of the MAOA coding sequences, encompassing 30 bp VNTR present in three, 3.5, four, and five copies. This has been termed the uVNTR polymorphism. This discovery has proved to be significant with regards to transcription efficiency. For example, MAO transcription is 2–10 times more efficient for alleles with 3.5 or four copies of the repeat in comparison to those with three or five copies.Citation89 Such results indicate an optimal length for the regulatory region, and suggest that the uVNTR variant alleles are associated with different levels of transcriptional activity.Citation89 This may result in variable MAOA expression.

Phenotypic studies into the uVNTR polymorphism have tried to determine the relationship between uVNTR-associated alleles and behaviors consistent with psychiatric disorders. The MAOA 4 repeat allele has been linked with an increased susceptibility to SB among males diagnosed with major depression.Citation90 A 2002 study,Citation91 however, found no associated between the uVNTR polymorphism and completed suicide. This contention suggests that further research into the association between the uVNTR polymorphism and SB is required.

5-HIAA

Serotonin is converted to 5-HIAA through the combined efforts of two enzymes, MAO and aldehyde dehydrogenase.Citation19 Asberg et al first displayed evidence of low cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) 5-HIAA levels in depressed suicides almost 40 years ago and since then, several studies have provided evidence that this metabolite is found in lower concentrations in the CSF of suicide victims.Citation92,Citation93 For instance, Mann and CurrierCitation94 report that over 20 retrospective studies have investigated an association between low CSF 5-HIAA levels and SB. Of these studies, several reported a significant association between SB and low 5-HIAA levels.Citation95–Citation98 These authors provide further evidence of prospective studies that also convey an elevated incidence of SB in follow-up amongst those with low CSF 5-HIAA, and they propose that serotonergic abnormalities in suicide attempters are distinctly localized to parts of the prefrontal cortex.Citation93,Citation99,Citation100 This information contrasts the more diffuse abnormalities in the postmortem tissue of patients with mood disorders, and may hint at a more localized depression of 5-HIAA in the brains of suicide victims.Citation101 As a result, the analysis of serotonergic function in the brains of suicide victims may require a more specific in vivo marker than total-body 5-HIAA concentrations due to the complexity or large numbers of physiological variables involved in modifying serotonergic signaling.

5-HT receptor family and associated polymorphisms

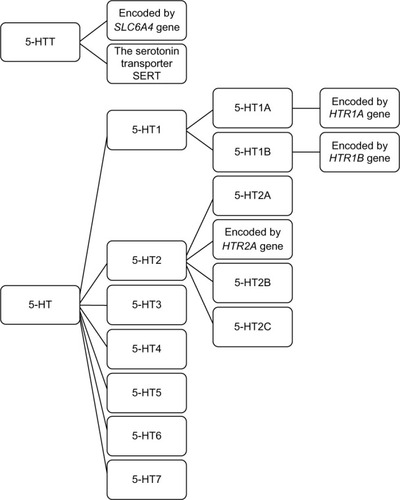

Upon the arrival of an action potential in the presynaptic serotonergic neuron, serotonin is released into the synaptic cleft where it may interact with both pre- and post-synaptic receptors. The activity of serotonin in the synaptic cleft is controlled by a group of 5-HTR embedded in the pre- and postsynaptic cell membranes, and in a transporter located in the presynaptic cell membrane.Citation19 The phenotypic and genotypic differences in the 5-HTR family of proteins and genes have been extensively studied in relation to many psychiatric disorders. presents an outline of the 5-HTR family.

Figure 1 Serotonin receptor family.

As an example, dysfunction of the 5-HTR1A receptor, which is believed to play a role in mood regulation, thermo-regulation, and food intake, is suggested to interfere with signaling in the progression of major depression, anxiety, and suicide.Citation23,Citation102,Citation103 Multiple studies have examined the quantity and activity of serotonergic receptors in the postmortem tissue samples and, more recently, they have provided sequencing data to uncover pertinent point mutations associated with SB (see Bach and ArangoCitation56 for a review). With regards to SB, the quantity, location, and activity of each receptor subtype may contribute to mechanisms responsible for altered mood, impulsivity, or behavior. Examination of the gene expression levels of these receptors in the serotonergic neurons of the raphe nucleus and cerebrum have shown significant differences in the brains of suicide victims.

5HT1A receptor

The 5HT1A receptors are responsible for mediating serotonin action and are encoded by the HTR1A gene located on the long arm of chromosome 5.Citation104–Citation106 In 1998, Göthert et alCitation107 identified three HTR1A polymorphisms that induce changes to amino acid sequence (gly22ser, ile28val, arg219leu). The ile28val variant was studied for binding properties and found to not differ significantly from the wild-type. However, the binding properties of the gly22ser variant were found to be altered in a way that suggests that individuals with the variant may experience altered sensitivity to antidepressants. This is due, in part, to the relationship between SSRIs and the 5-HT autoreceptor.Citation107

The C1019G polymorphism may be associated with SB in cases where individuals were exposed to highly traumatic life events.Citation108 However, general SNP studies have not shown associations between SB and other HTR1A variants.Citation109,Citation110

HT1B receptor (HTR1B)

The 5HT1B receptors, which function as presynaptic autoreceptors, are encoded by the HTR1B gene located on chromosome 6 at 6q13.Citation111 Several HTR1B polymorphisms have been identified. For example, a 2001 study conducted by Sanders et alCitation112 detected 12 HTR1B polymorphisms through denaturing gradient gel electorophoresis, database comparisons, and an analysis of previously published assays of HTR1B coding regions. Four such SNPs were found to induce amino acid substitutions: T655C (phe219leu); A1099G (ile367val); G1120A (glu374lys); and T371G (phe124cys). Thus, carriers of these mutations could experience a modified drug response. Of these mutations, the G1120A and T371G variants were found to be chemically conservative; thus, they can alter chemical properties of the resultant protein.Citation112 Alterations to the chemical properties of resultant proteins can sometimes impede the regular functioning of normal biological processes. The T371G mutation, which is located in the third transmembrane domain, may modify ligand-binding properties by interfering with disulphide bridge formation between the cysteine residues at 122 and 199.Citation112 Tests of binding properties found that the variant (T371G) is associated with significantly higher serotonin and sumatriptan binding affinities, as compared to the wild-type.Citation113 In addition, one should note that a review of family based case control studies by Sanders et alCitation114 found preliminary evidence to suggest a link between the HTR1B variant G861C with obsessive compulsive disorder. Such findings have major ramifications for the treatment of psychiatric patients with this HTR1B variant. Identifying genetic associations for psychiatric disorders allows us to personalize medicine; monitor patients better, and increase the standard and delivery of care through better surveillance methods. Other HTR1B polymorphisms include the C705T, C129T, and G861C variants, and an insertion/deletion between positions 181 and 182 (–182INS/DEL-181).Citation112 There is some evidence to suggest that the 129T and 861C alleles may be associated with decreased 5-HT1B binding.Citation115

When consulting the literature, one may notice that the primary focus of research on the HTR1B polymorphisms and SB has been on the G861C and C129T polymorphisms. Studies investigating these variants individually have yet to report a significant positive association between the variants and SB.Citation115–Citation118 As such, it is not yet known how these polymorphisms may affect SB.

5HT2A receptor (HTR2A)

The 5HT2A receptors are expressed postsynaptically throughout the limbic and cortical regions.Citation119 They are encoded by the HTR2A gene located at 13q14–q21.Citation120 A distinct characteristic of the 5HT2 receptors is the two or three introns they possess in their coding sequence.Citation120 In 1998, Göthert et alCitation107 identified two HTR2A polymorphisms that induce changes in amino acid sequence (thr25asn, his452tyr). These variants did not alter responsiveness to the antipsychotic clozapine, suggesting that the pharmacogenetic properties of the 5HT2A receptors are not significantly altered by the amino acid changes. Research into HTR2A polymorphisms in the context of SB has focused on the T102C SNP. It is important to note that the association between the T102C polymorphism and SB has been refuted in the current literature.Citation107 Results suggest that this variant is not associated with SB, with the majority of studies finding no significant differences in allele frequencies between suicidal patients and controls.Citation63,Citation67,Citation121–Citation123

5-HTT (SLC6A4)

The serotonin transporter, 5-HTT, is encoded by the SLC6A4 gene, located on the long arm of chromosome 17 (17q11.1–17q.12).Citation124 A 2001 study by Glatt et alCitation80 identified 15 polymorphisms in the coding regions of SLC6A4. Of these 15 polymorphisms, six were synonymous (C164T, C7T, T87C, C73T, G53A, and G113A) and nine induced changes to the amino acid sequence (T133A, G292A, E165K, S41F, P44L, L8M, I69V, K166N, and P43S).Citation80 These polymorphisms have yet to be investigated in relation to SB.

Perhaps one of the best studied polymorphisms of the serotonergic system is a 44 bp deletion/insertion polymorphism (5-HTTLPR), which is present in the 5′ flanking regulatory region of SLC6A4.Citation125 The corresponding alleles, termed the “L” or long allele, and the “s” or short allele, exhibit a dominant–recessive effect.Citation126 There are important implications for carriers of the L allele; these implications are that the basal transcription activity of 5-HTT promoters containing this L variant is more than twice that of promoters with the s form.Citation126 In lymphoblast cell lines, cells homozygous for the L allele produced concentrations of 5-HTT mRNA that were 1.4 to 1.7 times higher than those of cells containing one or two copies of the s variant.Citation126 In addition, Lesch et alCitation126 noted that “H-serotonin uptake in cells homozygous for the l allele was 1.9 to 2.2 times that in cells carrying one or two endogenous copies of the s variant.”

Several studies have investigated the association between the 5-HTTLPR s/L polymorphism and SB. The frequency of the LL genotype has been found to be significantly higher in depressed suicide victims as compared to controls.Citation71 Individuals who reattempted suicide have been shown to have significantly higher frequencies of the homozygous (ss) genotype.Citation66 However, one should not that other studies have failed to replicate these findings,Citation63,Citation123,Citation127 thus highlighting the importance of further research into this area.

Discussion

Since the discovery of serotonin almost 60 years ago, a great amount of research has amassed, implicating a role for the serotonergic system in the neurobiology of SB. The measurement of CSF serotonin metabolites in the 1970s and postmortem receptor binding studies in the 1980s opened the gate to a vast proteomic and genomic analysis of the serotonin system in the brains of suicide victims. Recent genome-wide linkage studies and meta-analyses of genetic association studies have implicated a variety of genes involved in neurotransmission, including those within the noreadrenergic, dopaminergic, and gamma-aminobutyric acid systems not discussed here. Clarified definitions of the spectrum of suicide behavior will help uncover greater trends in genetic associations, and will reduce heterogeneity amongst pooled results. Future proteomic studies within the serotonergic system will focus on eliminating confounding variables, such as sex and medication use, and aid in identifying the link between genetic polymorphisms and the functional activity of receptors in pre- and postsynaptic membranes.

These studies will hopefully elucidate both the local and global differences between serotonin neurotransmission in the prefrontal cortex of suicide victims and controls. In addition, longitudinal studies on the effects of antidepressants on suicidal risk will help clarify the proper use of psycho pharmacology in adolescent mood disorders and depression. Research regarding the serotonergic system remains an extremely promising field of study that will undoubtedly become more prominent in the study of SB in the future.

The serotonergic system is instrumental in mood regulation. As such, it follows that deregulated serotonergic function is associated with various psychiatric disorders including depression and generalized anxiety disorder.Citation128,Citation129 These psychiatric disorders have a significant impact on the lives of the populations that suffer from them, highlighting the importance of research needed in this field. While several studies have noted an association between altered serotonergic function and SB, this review has taken an approach to extensively explore this topic at a chemical and cellular level. Low CSF serotonin and 5-HIAA levels have been detected in postmortem studies of suicide victims.Citation130 In addition, increased densities of 5-HT2A receptors have been found in brain tissues of depressed suicide victims.Citation131–Citation133 In light of this evidence, it is possible that the mutations that impede serotonin production may contribute to a suicidal phenotype. Polymorphisms that alter transcriptional activity (5-HTTLPR s/L in SLC6A4; uVNTR in MAOA) may contribute to irregular serotonin levels insofar as the genes encoding serotonergic enzymes or receptors may be atypically expressed. However, more research into this area is required.

Gene variants associated with altered ligand-binding properties (gly22ser and ile28val in HTR1A; phe124cys, C129T, and G861C in HTR1B; thr68met and met453ile in SLC18A2) may alter sensitivity to serotonin and certain medications. For instance, phe124cys has been found to increase affinity for sumatriptan (a 5-HT1B agonist that is similar in structure to serotonin). Such findings have implications for the pharmacological treatment of SB.

Differences that could be found in protein levels and mRNA levels coding for a particular protein are particularly important when investigating the influence of serotonergic genes on SB. Several polymorphisms have been found to alter amino acid sequence (thr68met, thr249met, met453ile, thr82met, and met53ile in SLC18A2; gly22ser, ile28val, and arg219leu in HTR1A; phe219cys, ile367val, glu374lys, and phe124cys in HTR1B; thr25asn and his452tyr in HTR2A). Subsequently, several of these variants have been associated with alterations to chemical and ligand-binding properties. More research is required to elucidate the effects that DDC polymorphisms (rs1451371, rs1470750, and rs998850), TPH polymorphisms (A6526G and G5806T), and the HTR1B (−182INS/DEL-181) may have on protein function or expression.

Associations have been made between certain genes and SB types. After consulting the literature, one is better able to differentiate between the genes that are currently accepted as having a positive association with SB, and certain genes that do not share this same correlation. Currently, we know the polymorphisms A779C, A218C, A6526G, and G5806T (TPH), 5-HTTLPR s/L (SLC6A4), C1019G (HTR1A), rs1451371, rs1470750, rs998850 (DDC), and uVNTR (MAOA) have been found to be associated with SB in some studies. We also know that the polymorphisms gly22ser, ile28val, arg219leu (HTR1A), C129T, G861C (HTR1B), and T102C (HTR2A) have not been found to be associated with SB. Meta-analyses of SB candidate gene studies yield many inconsistent results.Citation134,Citation135 Several studies noting positive associations between candidate genes and SB have failed to be replicated. A number of factors may contribute to the lack of consensus in study results, including the heterogeneous nature of SB and any methodological shortcomings.

There are many methodological differences in the selected studies for this review, which arguably has a serious influence on the inconsistent results presented. For example, the Bellivier et alCitation70 study exclusively investigated patients with bipolar affective disorder in the SB group; this is a stark difference to other studies that included suicidal patients with various psychiatric diagnoses.Citation17 It is important to look at all psychiatric diagnoses when evaluating different patients engaging in suicidal behavior.

A major impediment to research into the genetics of SB is the lack of consistency in how “suicidal behavior” is defined. As with many psychiatric disorders, SB falls on a spectrum. SB phenotypes may range from suicidal ideation to suicide attempts, through to completed suicide. Many studies choose to limit their focus to a certain SB “phenotype”, such as violent or nonviolent suicide. As such, it is difficult to draw appropriate comparisons between study results. A related issue is the absence of a universal system for classifying polymorphisms. Several of the polymorphisms summarized in this review were associated with multiple identifiers, which hinder the meta-analysis. A uniform definition for SB and a universal system for classifying polymorphisms are recommended.

Research into SB is complicated by the condition’s multifaceted nature. Current research is guided by the understanding that susceptibility to SB is mediated by a complex interplay between genes and the environment. Recent reviews have addressed the innate difficulties of studying SB and other etiologically complex conditions.Citation68,Citation136,Citation137 One of these innate difficulties is the problem of methodological complexities in SB genetic studies. A 2009 workshop convened by the American Foundation for Suicide Prevention, the Department of Psychiatry at Columbia University, and the National Institute of Mental HealthCitation136 identified strategies for circumventing methodological difficulties associated with SB genetic studies. One such strategy is the implementation of an endophenotype approach, which is aimed at identifying genes associated with heritable intermediate phenotypes such as aggression/impulsivity and early-onset major depression. This approach may assist in mitigating gene–gene interactions and other confounding factors inherent to candidate gene research.

Research into the genetics of SB may also benefit from the genome-wide association studies measuring linkage disequilibrium, or nonrandom association, of key SB alleles.Citation138 Gene expression arrays may offer insights into the epigenetics of SB. Epigenetic events such as deoxyribonucleic acid methylation or chromatin remodeling may alter gene expression, possibly resulting in phenotypic changes relevant to SB. Epigenetic events can be altered by environmental factors, and they may provide insights into the mechanics of gene–environment interactions.Citation136 While gene expression arrays are prone to type 2 statistical errors, secondary assay methods such as in situ hybridization histochemistry and modified statistical methods may compensate for potential methodological shortcomings.Citation136

Conclusion

This review sought to investigate the role of genetic variants in the serotonergic system on the pathophysiology of SB. A search of the PubMed, PsycINFO®, and Web of Knowledge® databases revealed ten key serotonergic genes (TPH1, TPH2, SLC6A4, SLC18A2, HTR1A, HTR1B, HTR2B, DDC, MAOA, and MAOB), and over 30 associated polymorphisms, which have been studied in the context of SB. After extensive investigation into the topic, no conclusive findings could be drawn from the studies reviewed. Inconsistencies between study results suggest that alternate research approaches may help bridge our current gaps in knowledge. The implementation of an endotype or epigenetic approach in future studies is recommended.

Acknowledgments

This work is supported by the Brain and Behavior Research Foundation, New Investigator Funding, grant award number 19058.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- RapportMMGeenAAPageIHSerum vasoconstrictor, serotonin; isolation and characterizationJ Biol Chem194817631243125118100415

- ErspramerVAseroBIdentification of enteramine, the specific hormone of the enterochromaffin cell system, as 5-hydroxytryptamineNature19521694306800801

- TwarogBMPageIHSerotonin content of some mammalian tissues and urine and a method for its determinationAm J Physiol1953175115716113114371

- SullivanPFNealeMCKendlerKSGenetic epidemiology of major depression: review and meta-analysisAm J Psychiatry20001571015526211007705

- CôtéFFlignyCFromesYMalletJVodjdaniGRecent advances in understanding serotonin regulation of cardiovascular functionTrends Mol Med200410523223815121050

- WaltherDJPeterJUBashammakhSSynthesis of serotonin by a second tryptophan hydroxylase isoformScience200329956037612511643

- NilssonTLongmoreJShawDCharacterisation of 5-HT receptors in human coronary arteries by molecular and pharmacological techniquesEur J Pharmacol19993721495610374714

- YildizOSmithJRPurdyRESerotonin and vasoconstrictor synergismLife Sci19986219172317329585103

- YusufSAl-SaadyNCammAJ5-hydroxytryptamine and atrial fibrillation: how significant is this piece in the puzzle?J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol200314220921412693508

- GershonMDTackJThe serotonin signaling system: from basic understanding to drug development for functional GI disordersGastroenterology2007132139741417241888

- KirchgessnerALLiuMTGershonMDIn situ identification and visualization of neurons that mediate enteric and enteropancreatic reflexesJ Comp Neurol199637122702868835732

- KirchgessnerALTamirHGershonMDIdentification and stimulation by serotonin of intrinsic sensory neurons of the submucosal plexus of the guinea pig gut: activity-induced expression of Fos immunoreactivityJ Neurosci19921212352481729436

- CookeHJSidhuMWangYZ5-HT activates neural reflexes regulating secretion in the guinea-pig colonNeurogastroenterol Motil1997931811869347474

- KimMCookeHJJavedNHCareyHVChristofiFRaybouldHED-glucose releases 5-hydroxytryptamine from human BON cells as a model of enterochromaffin cellsGastroenterology200112161400140611729119

- SidhuMCookeHJRole for 5-HT and ACh in submucosal reflexes mediating colonic secretionAm J Physiol19952693 Pt 1G346G3517573444

- PanHGershonMDActivation of intrinsic afferent pathways in submucosal ganglia of the guinea pig small intestineJ Neurosci20002093295330910777793

- BulbringECremaAObservations concerning the action of 5- hydroxytryptamine on the peristaltic reflexBr J Pharmacol Chemother195813444445713618550

- TörkIAnatomy of the serotonergic systemAnn N Y Acad Sci1990600934 discussion 34–352252340

- LeschKPAraragiNWaiderJvan den HoveDGutknechtLTargeting brain serotonin synthesis: insights into neurodevelopmental disorders with long-term outcomes related to negative emotionality, aggression and antisocial behaviourPhilos Trans R Soc Lond, B, Biol Sci201236716012426244322826343

- AndradeCSandarshSChethanKBNageshKSSerotonin reuptake inhibitor antidepressants and abnormal bleeding: a review for clinicians and a reconsideration of mechanismsJ Clin Psychiatry201071121565157521190637

- World Health OrganizationSuicide prevention (SUPRE)20122012

- Ministry of Health PromotionPrevention of Injury: Guidance DocumentToronto, ONStandards, Programs and Community Development Branch, Ministry of Health Promotion2010

- MannJJNeurobiology of suicidal behaviorNat Rev Neurosci200341081982814523381

- Practice guideline for the assessment and treatment of patients with suicidal behaviorsAm J Psychiatry2003160Suppl 11160

- FowlerJCSuicide risk assessment in clinical practice: pragmatic guidelines for imperfect assessmentsPsychotherapy (Chic)2012491819022369082

- GuzeSBRobinsESuicide and primary affective disordersBr J Psychiatry19701175394374385481206

- RunesonBMental disorder in youth suicide. DSM-III-R Axes I and IIActa Psychiatr Scand19897954904972750550

- BeautraisALJoycePRMulderRTFergussonDMDeavollBJNightingaleSKPrevalence and comorbidity of mental disorders in persons making serious suicide attempts: a case-control studyAm J Psychiatry19961538100910148678168

- SareenJCoxBJAfifiTOAnxiety disorders and risk for suicidal ideation and suicide attempts: a population-based longitudinal study of adultsArch Gen Psychiatry200562111249125716275812

- ClementsCMorrissRJonesSPetersSRobertsCKapurNSuicide in bipolar disorder in a national English sample, 1996–2009: frequency, trends and characteristicsPsychol Med201311023510515

- DiaconuGTureckiGObsessive-compulsive personality disorder and suicidal behavior: evidence for a positive association in a sample of depressed patientsJ Clin Psychiatry200970111551155619607764

- MandelliLSerrettiAGene environment interaction studies in depression and suicidal behavior: an updateNeurosci Biobehav Rev Epub July 22, 2013

- PaykelESLife stress, depression and attempted suicideJ Human Stress197623312

- World Health OrganizationPrevention of Mental Disorders: Effective Interventions and Policy Options, Summary ReportGeneva, SwitzerlandWorld Health Organization2004

- LinkowskaKDacaPSykuteraMPufalEBloch-BogusławskaEGrzybowskiTSearch for association between suicide and 5-HTT, MAOA and DAT polymorphism in Polish malesArch Med Sadowej Kryminol2010602–311211721516943

- RoyAFamily history of suicideArch Gen Psychiatry19834099719746615160

- RoyASegalNLSarchiaponeMAttempted suicide among living co-twins of twin suicide victimsAm J Psychiatry19951527107510767793447

- GouldMSFisherPParidesMFloryMShafferDPsychosocial risk factors of child and adolescent completed suicideArch Gen Psychiatry19965312115511628956682

- BrentDAMannJJFamily genetic studies, suicide, and suicidal behaviorAm J Med Genet C Semin Med Genet2005133C1132415648081

- MannJJBrentDAArangoV2001The neurobiology and genetics of suicide and attempted suicide: a focus on the serotonergic systemNeuropsychopharmacology2446747711282247

- StanleyMMannJJSuicide and serotonin receptorsLancet1984183723496141420

- StanleyMMannJJIncreased serotonin-2 binding sites in frontal cortex of suicide victimsLancet1983183182142166130248

- StanleyMVirgilioJGershonSTritiated imipramine binding sites are decreased in the frontal cortex of suicidesScience19822164552133713397079769

- HughesJHDunneFYoungAHEffects of acute tryptophan depletion on mood and suicidal ideation in bipolar patients symptomatically stable on lithiumBr J Psychiatry200017744745111059999

- McCloskeyMSBen-ZeevDLeeRBermanMECoccaroEFAcute tryptophan depletion and self-injurious behavior in aggressive patients and healthy volunteersPsychopharmacology (Berl)20092031536118946662

- SubletteMEGalfalvyHCFuchsDPlasma kynurenine levels are elevated in suicide attempters with major depressive disorderBrain Behav Immun20112561272127821605657

- De PontiFToniniMIrritable bowel syndrome: new agents targeting serotonin receptor subtypesDrugs200161331733211293643

- WongDTBymasterFPDevelopment of antidepressant drugs. Fluoxetine (Prozac) and other selective serotonin uptake inhibitorsAdv Exp Med Biol199536377957618533

- HammadTALaughrenTRacoosinJSuicidality in pediatric patients treated with antidepressant drugsArch Gen Psychiatry200663333233916520440

- GunnellDSaperiaJAshbyDSelective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) and suicide in adults: meta-analysis of drug company data from placebo controlled, randomised controlled trials submitted to the MHRA’s safety reviewBMJ2005330748838515718537

- HetrickSEMcKenzieJECoxGRSimmonsMBMerrySNNewer generation antidepressants for depressive disorders in children and adolescentsCochrane Database Syst Rev201211CD00485123152227

- TondoLBaldessariniRJLong-term lithium treatment in the prevention of suicidal behavior in bipolar disorder patientsEpidemiol Psichiatr Soc200918317918320034193

- GibbonsRMannJJProper studies of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors are needed for youth with depressionCMAJ2009180327027119188617

- NakagawaAGrunebaumMFEllisSPAssociation of suicide and antidepressant prescription rates in Japan, 1999–2003J Clin Psychiatry200768690891617592916

- CastelpietraGMorsanuttoAPascolo-FabriciEIsacssonGAntidepressant use and suicide prevention: a prescription database study in the region Friuli Venezia Giulia, ItalyActa Psychiatr Scand2008118538238818754835

- BachHArangoVChapter 2: Neuroanatomy of serotonergic abnormalities in suicideDwivediYThe Neurobiological Basis of SuicideBoca Raton, FLCRC Press2012 Available online: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov.libaccess.lib.mcmaster.ca/books/NBK107204/

- YoonHKKimYKTPH2-703G/T SNP may have important effect on susceptibility to suicidal behavior in major depressionProg Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry200933340340919162119

- PatelPDPontrelloCBurkeSRobust and tissue-specific expression of TPH2 versus TPH1 in rat raphe and pineal glandBiol Psychiatry200455442843314960297

- KatzungBGBasic and Clinical PharmacologyNew York, NYMcGraw-Hill Medical2007

- NielsenDAJenkinsGLStefaniskoKMJeffersonKKGoldmanDSequence, splice site and population frequency distribution analyses of the polymorphic human tryptophan hydroxylase intron 7Brain Res Mol Brain Res19974511451489105682

- NielsenDAGoldmanDVirkkunenMTokolaRRawlingsRLinnoilaMSuicidality and 5-hydroxyindoleacetic acid concentration associated with a tryptophan hydroxylase polymorphismArch Gen Psychiatry199451134387506517

- BennettPJMcMahonWMWatabeJTryptophan hydroxylase polymorphisms in suicide victimsPsychiatr Genet2000101131710909123

- GeijerTFrischAPerssonMLSearch for association between suicide attempt and serotonergic polymorphismsPsychiatr Genet2000101192610909124

- KollerGEngelRRPreussUWTryptophan hydroxylase gene 1 polymorphisms are not associated with suicide attempts in alcohol-dependent individualsAddict Biol200510326927316109589

- SaetrePLundmarkPWangA2010The tryptophan hydroxylase 1 (TPH1) gene, schizophrenia susceptibility, and suicidal behavior: a multi-centre case-control study and meta-analysisAm J Med Genet B Neuropsychiatr Genet153B38739619526457

- CourtetPJollantFCastelnauDAstrucBBuresiCMalafosseAImplication of genes of the serotonergic system on vulnerability to suicidal behaviorJ Psychiatry Neurosci2004295350359 French15534946

- YoonHKKimYKAssociation between serotonin-related gene polymorphisms and suicidal behavior in depressive patientsProg Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry20083251293129718502553

- TsaiSJHongCJWangYCTryptophan hydroxylase gene polymorphism (A218C) and suicidal behaviorsNeuroreport199910183773377510716208

- RujescuDGieglingISatoTHartmannAMMöllerHJGenetic variations in tryptophan hydroxylase in suicidal behavior: analysis and meta-analysisBiol Psychiatry200354446547312915291

- BellivierFChastePMalafosseAAssociation between the TPH gene A218C polymorphism and suicidal behavior: a meta-analysisAm J Med Genet B Neuropsychiatr Genet2004124B1879114681922

- DuLFaludiGPalkovitsMBakishDHrdinaPDSerotonergic genes and suicidalityCrisis2001222546011727894

- RotondoASchuebelKBergenAIdentification of four variants in the tryptophan hydroxylase promoter and association to behaviorMol Psychiatry19994436036810483053

- TureckiGZhuZTzenovaJTPH and suicidal behavior: a study in suicide completersMol Psychiatry2001619810211244493

- BrunLNguLHKengWTClinical and biochemical features of aromatic L-amino acid decarboxylase deficiencyNeurology2010751647120505134

- Sumi-IchinoseCIchinoseHTakahashiEHoriTNagatsuTMolecular cloning of genomic DNA and chromosomal assignment of the gene for human aromatic L-amino acid decarboxylase, the enzyme for catecholamine and serotonin biosynthesisBiochemistry1992318222922381540578

- SpeightGTuricDAustinJComparative sequencing and association studies of aromatic L-amino acid decarboxylase in schizophrenia and bipolar disorderMol Psychiatry20005332733110889538

- GieglingIMoreno-De-LucaDRujescuDDopa decarboxylase and tyrosine hydroxylase gene variants in suicidal behaviorAm J Med Genet B Neuropsychiatr Genet2008147330831517948905

- SurrattCKPersicoAMYangXDA human synaptic vesicle monoamine transporter cDNA predicts posttranslational modifications, reveals chromosome 10 gene localization and identifies TaqI RFLPsFEBS Lett199331833253308095030

- PeterDFinnJPKlisakIChromosomal localization of the human vesicular amine transporter genesGenomics19931837207237905859

- GlattCEDeYoungJADelgadoSScreening a large reference sample to identify very low frequency sequence variants: comparisons between two genesNat Genet200127443543811279528

- BurmanJTranCHGlattCFreimerNBEdwardsRHThe effect of rare human sequence variants on the function of vesicular monoamine transporter 2Pharmacogenetics200414958759415475732

- TrowbridgeSNarboux-NêmeNGasparPGenetic models of serotonin (5-HT) depletion: what do they tell us about the developmental role of 5-HT?Anat Rec (Hoboken)2011294101615162320818612

- OzeliusLHsuYPBrunsGHuman monoamine oxidase gene (MAOA): chromosome position (Xp21-p11) and DNA polymorphismGenomics19883153582906043

- ClaydenRCZarukAMeyreDThabaneLSamaanZThe association of attempted suicide with genetic variants in the SLC6A4 and TPH genes depends on the definition of suicidal behavior: a systematic review and meta-analysisTransl Psychiatry20122e16623032942

- HungCFLungFWHungTHMonoamine oxidase A gene polymorphism and suicide: an association study and meta-analysisJ Affect Disord2012136364364922041522

- MannJJStanleyMPostmortem monoamine oxidase enzyme kinetics in the frontal cortex of suicide victims and controlsActa Psychiatr Scand19846921351396702476

- SherifFMarcussonJOrelandLBrain gamma-aminobutyrate transaminase and monoamine oxidase activities in suicide victimsEur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci199124131391441790159

- LanNCHeinzmannCGalAHuman monoamine oxidase A and B genes map to Xp 11.23 and are deleted in a patient with Norrie diseaseGenomics1989445525592744764

- SabolSZHuSHamerDA functional polymorphism in the monoamine oxidase A gene promoterHum Genet199810332732799799080

- LungFWTzengDSHuangMFLeeMBAssociation of the MAOA promoter uVNTR polymorphism with suicide attempts in patients with major depressive disorderBMC Med Genet2011127421605465

- OnoHShirakawaONishiguchiNNo evidence of an association between a functional monoamine oxidase a gene polymorphism and completed suicidesAm J Med Genet2002114334034211920860

- AsbergMNeurotransmitters and suicidal behavior. The evidence from cerebrospinal fluid studiesAnn N Y Acad Sci19978361581819616798

- AsbergMTräskmanLThorénP5-HIAA in the cerebrospinal fluid. A biochemical suicide predictor?Arch Gen Psychiatry1976331011931197971028

- MannJJCurrierDA review of prospective studies of biologic predictors of suicidal behavior in mood disordersArch Suicide Res200711131617178639

- JokinenJNordströmALNordströmPCerebrospinal fluid mono-amine metabolites and suicideNord J Psychiatry200963427627919034712

- SamuelssonMJokinenJNordströmALNordströmPCSF 5-HIAA, suicide intent and hopelessness in the prediction of early suicide in male high-risk suicide attemptersActa Psychiatr Scand20061131444716390368

- TräskmanLAsbergMBertilssonLSjöstrandLMonoamine metabolites in CSF and suicidal behaviorArch Gen Psychiatry19813866316366166274

- LinnoilaMVirkkunenMScheininMNuutilaARimonRGoodwinFKLow cerebrospinal fluid 5-hydroxyindoleacetic acid concentration differentiates impulsive from nonimpulsive violent behaviorLife Sci19833326260926146198573

- NordstömPAsgårdUSuicide risk by age and birth cohort in SwedenCrisis19867275803780276

- OquendoMAPlacidiGPMaloneKMPositron emission tomography of regional brain metabolic responses to a serotonergic challenge and lethality of suicide attempts in major depressionArch Gen Psychiatry2003601142212511168

- MilakMSParseyRVKeilpJOquendoMAMaloneKMMannJJNeuroanatomic correlates of psychopathologic components of major depressive disorderArch Gen Psychiatry200562439740815809407

- RaymondJRMukhinYVGelascoAMultiplicity of mechanisms of serotonin receptor signal transductionPharmacol Ther2001922–317921211916537

- BlierPListaADe MontignyCDifferential properties of pre- and postsynaptic 5-hydroxytryptamine1A receptors in the dorsal raphe and hippocampus: I. Effect of spiperoneJ Pharmacol Exp Ther199326517158474032

- KobilkaBKFrielleTCollinsSAn intronless gene encoding a potential member of the family of receptors coupled to guanine nucleotide regulatory proteinsNature1987329613475793041227

- DavidSPMurthyNVRabinerEAA functional genetic variation of the serotonin (5-HT) transporter affects 5-HT1A receptor binding in humansJ Neurosci200525102586259015758168

- HettemaJMAnSSvan den OordEJNealeMCKendlerKSChenXAssociation study between the serotonin 1A receptor (HTR1A) gene and neuroticism, major depression, and anxiety disordersAm J Med Genet B Neuropsychiatr Genet2008147B566166618163385

- GöthertMProppingPBönischHBrüssMNöthenMMGenetic variation in human 5-HT receptors: potential pathogenetic and pharmacological roleAnn N Y Acad Sci199886126309928235

- WassermanDGeijerTSokolowskiMRozanovVWassermanJThe serotonin 1A receptor C(-1019)G polymorphism in relation to suicide attemptBehav Brain Funct200621416626484

- SerrettiAMandelliLGieglingIHTR2C and HTR1A gene variants in German and Italian suicide attempters and completersAm J Med Genet B Neuropsychiatr Genet2007144B329129917192951

- VideticAZupancTPregeljPBalazicJTomoriMKomelRSuicide, stress and serotonin receptor 1A promoter polymorphism -1019C>G in Slovenian suicide victimsEur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci2009259423423819224112

- JinHOksenbergDAshkenaziCharacterization of the human 5-hydroxytryptamine 1B receptorJ Biol Chem19922679573557381348246

- SandersARCaoQTaylorJGenetic diversity of the human serotonin receptor 1B (HTR1B) geneGenomics200172111411247661

- KielSBrüssMBönischHGöthertMPharmacological properties of the naturally occurring Phe-124-Cys variant of the human 5-HT1B receptor: changes in ligand binding, G-protein coupling and second messenger formationPharmacogenetics200010765566611037806

- SandersARDuanJGejmanPVDNA variation and psychopharmacology of the human serotonin receptor 1B (HTR1B) genePharmacogenomics20023674576212437478

- HuangYYGrailheRArangoVHenRMannJJRelationship of psychopathology to the human serotonin1B genotype and receptor binding kinetics in postmortem brain tissueNeuropsychopharmacology199921223824610432472

- StefuljJBüttnerASkavicJSerotonin 1B (5HT-1B) receptor polymorphism (G861C) in suicide victims: association studies in German and Slavic populationAm J Med Genet B Neuropsychiatr Genet2004127B1485015108179

- RujescuDGieglingISatoTMöllerHJLack of association between serotonin 5-HT1B receptor gene polymorphism and suicidal behaviorAm J Med Genet B Neuropsychiatr Genet2003116B1697112497617

- NishiguchiNShirakawaOOnoHNo evidence of an association between 5HT1B receptor gene polymorphism and suicide victims in a Japanese populationAm J Med Genet2001105434334511378847

- Cornea-HébertVRiadMWuCSinghSKDescarriesLCellular and subcellular distribution of the serotonin 5-HT2A receptor in the central nervous system of adult ratJ Comp Neurol1999409218720910379914

- BarnesNMSharpTA review of central 5-HT receptors and their functionNeuropharmacology19993881083115210462127

- ZhangJShenYHeGLack of association between three serotonin genes and suicidal behavior in Chinese psychiatric patientsProg Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry200832246747117964050

- ErtugrulAKennedyJLMasellisMBasileVSJayathilakeKMeltzerHYNo association of the T102C polymorphism of the serotonin 2A receptor gene (HTR2A) with suicidality in schizophreniaSchizophr Res2004692–330130515469201

- PooleyECHoustonKHawtonKHarrisonPJDeliberate self-harm is associated with allelic variation in the tryptophan hydroxylase gene (TPH A779C), but not with polymorphisms in five other serotonergic genesPsychol Med200333577578312877392

- RamamoorthySLeibachFHMaheshVBGanapathyVPartial purification and characterization of the human placental serotonin transporterPlacenta19931444494618248037

- HeilsATeufelAPetriSAllelic variation of human serotonin transporter gene expressionJ Neurochem1996666262126248632190

- LeschKPBengelDHeilsAAssociation of anxiety-related traits with a polymorphism in the serotonin transporter gene regulatory regionScience19962745292152715318929413

- MergenHDemirelBAkarTSenolELack of association between the serotonin transporter and tryptophan hydroxylase gene polymorphisms and completed suicidePsychiatr Genet20061625316538180

- OwensMJNemeroffCBRole of serotonin in the pathophysiology of depression: focus on the serotonin transporterClin Chem19944022882957508830

- ResslerKJNemeroffCBRole of serotonergic and noradrenergic systems in the pathophysiology of depression and anxiety disordersDepress Anxiety200012Suppl 121911098410

- AsbergMNordströmPTräskman-BendzLCerebrospinal fluid studies in suicide. An overviewAnn N Y Acad Sci19864872432552436537

- HrdinaPDDemeterEVuTBSótónyiPPalkovitsM5-HT uptake sites and 5-HT2 receptors in brain of antidepressant-free suicide victims/depressives: increase in 5-HT2 sites in cortex and amygdalaBrain Res19936141–237448348328

- TureckiGBrièreRDewarKPrediction of level of serotonin 2A receptor binding by serotonin receptor 2A genetic variation in postmortem brain samples from subjects who did or did not commit suicideAm J Psychiatry199915691456145810484964

- ArangoVErnsbergerPMarzukPMAutoradiographic demonstration of increased serotonin 5-HT2 and beta-adrenergic receptor binding sites in the brain of suicide victimsArch Gen Psychiatry19904711103810472173513

- Gonzalez-CastroTBTovilla-ZarateCAJuarez-RojopIPoolGarcia SGenisA2013Association of 5HTR1A gene variants with suicidal behavior: Case-control study and updated meta-analysisJ Psychiatr Res

- AnguelovaMBenkelfatCTureckiG2003A systematic review of association studies investigating genes coding for serotonin receptors and the serotonin transporter: II. Suicidal behaviorMol Psychiatry864665312874600

- MannJJArangoVAAvenevoliSCandidate endopheno-types for genetic studies of suicidal behaviorBiol Psychiatry200965755656319201395

- BrezoJKlempanTTureckiGThe genetics of suicide: a critical review of molecular studiesPsychiatr Clin North Am200831217920318439443

- PerasonTAManolioTAHow to interpret a genome-wide association studyJAMA2008299111335134418349094

- DuLFaludiGPalkovitsMBakishDHrdinaPDTryptophan hydroxylase gene 218A/C polymorphism is not associated with depressed suicideInt J Neuropsychopharmacol20003321522011343598

- ZalsmanGFrischAKingRACase control and family-based studies of tryptophan hydroxylase gene A218C polymorphism and suicidality in adolescentsAm J Med Genet2001105545145711449398

- SerrettiACalatiRGieglingIHartmannAMMöllerHJRujescuDSerotonin receptor HTR1A and HTR2C variants and personality traits in suicide attempters and controlsJ Psychiatr Res200943551952518715570

- StefuljJKubatMBalijaMSkavicJJernejBVariability of the tryptophan hydroxylase gene: study in victims of violent suicidePsychiatry Res20051341677315808291

- VideticAZupancTPregeljPBalazicJTomoriM2009Suicide, stress and serotonin receptor 1A promoter polymorphism -1019C>G in Slovenian suicide victimsEur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci25923423819224112