Abstract

Background

This study aims to verify the main psychometric properties of the Italian version of the Impact of Event Scale – Revised (IES-R) in a sample of flood victims.

Methods

The sample was composed of 262 subjects involved in the natural disaster of 2009 in the city of Messina (Italy). All participants completed the IES-R and the Dissociative Experiences Scale-II (DES-II) in order to verify some aspects of convergent validity.

Results

The exploratory and confirmatory factor analysis, used to verify the construct validity of the measure, showed a clear factor structure with three independent dimensions: intrusion, avoidance, and hyper-arousal. The goodness-of-fit indices (non-normed fit index [NNFI] = 0.99; comparative fit index [CFI] = 0.99; standardized root mean square residual [SRMR] = 0.04; and root mean square error of approximation [RMSEA] = 0.02) indicated a good adaptation of the model to the data. The IES-R scales showed satisfactory values of internal consistency (intrusion, α = 0.78; avoidance, α = 0.72; hyper-arousal, α = 0.83) and acceptable values of correlation with the DES-II.

Conclusion

These results suggest that this self-reported and easily administered instrument for assessing the dimensions of trauma has good psychometric properties and can be adopted usefully, both for research and for practice in Italy.

Keywords:

Introduction

In the latest edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM),Citation1 post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) has been included in a new category, ‘trauma and stress-related disorders.’ The essential feature of PTSD is the development of symptoms associated with “exposure to actual threatened death, serious injury, or sexual violence.” One of the essential characteristics of PTSD is also the presence of dissociative symptoms (eg, flashbacks) “in which the individual feels or acts as if the traumatic event(s) were recurring.” Furthermore, the dissociative states are considered a peculiarity of diagnosis for PTSD, different from the description in the previous edition (DSM fourth edition, text revision [DSM-IV-TR]). Several studies have demonstrated a frequent association between post-traumatic syndromes and other psychological diseases, such as depression, addiction, eating disorders, anxiety, and personality disorders.Citation2–Citation6

Horowitz et alCitation7 developed The Impact of Event Scale (IES) to evaluate the impact of several traumatic experiences.Citation8–Citation10 This instrument has been translated and validated in different studies.Citation11–Citation17

The IES-RCitation18 is a revised version of the IES and was developed because the original version did not include a hyper-arousal subscale. There are several translations of this self-report.Citation19–Citation24 Both versions have shown good psychometric properties. Test–retest reliability (r = 0.89–0.94) and internal consistency (Cronbach’s α) for each subscale (intrusion = 0.87–0.94, avoidance = 0.84–0.97, hyper-arousal = 0.79–0.91) are acceptable.Citation18 Correlations have been found to be high between those of the IES-R and the original IES for the intrusion (r = 0.86) and avoidance (r = 0.66) subscales, which supports the concurrent validity of both measures.Citation25 Despite its good psychometric properties, the factorial structure of the IES-R is debated; for example, King et alCitation26 found a four-factor structure composed of intrusion, avoidance–numbing, hyper-arousal, and sleep disturbance. However, it is still not completely clear if these different data regarding the factorial structure of the IES-R are related to the cultural differences between samples. Thus, it would be useful, and would help improve the diagnostic capacities of the IES-R, to investigate some aspects related to the validity (including predictive and discriminant validity) of the measure in different samples. For the IES-R, as for other widely used self-report measures that have been translated into many languages,Citation27–Citation30 it is valuable to present additional empirical data regarding the evaluation of the psychometric properties of the scale.

The present study

The purpose of the present study is to assess the main psychometric properties of the IES-R in an Italian context.

Methods

Participants and procedure

A total of 262 young adults (57.6% men and 42.4% women) participated in this study. The mean age of the participants was 18.4 years (standard deviation [SD] = 0.64; range 16–21). We randomly recruited a group of Italian young adults involved in the natural disaster (floods and mudslides) of 2009 in the city of Messina (Sicily, Italy) that resulted in 18 dead, 35 missing, 79 injured, and 400 homeless. We administered the scale 27 months after the event.

Participants were informed about the aim of the research, and a strong emphasis was put on data confidentiality. All subjects gave informed consent.

Measures

IES-R

The IES-RCitation18 is a self-report measure of current subjective distress in response to a specific traumatic event. It comprises three subscales representative of the major symptom clusters of post-traumatic stress: intrusion, avoidance, and hyper-arousal.

The English version of the IES-R was translated independently into Italian by a bilingual Italian English teacher. The two translations were then compared, and no differences were found between them. The first final version was given to several bilingual individuals who also completed the English version and provided feedback on differences found in certain items between the English version and the translated version. Based on their comments, a final translation was created. This version was back translated into English by two bilingual psychologists with doctoral degrees who were familiar with psychology. After comparing the back translation with the original inventory, we made several minor revisions. The back-translation procedures were similar to those used in previous studies.Citation31,Citation32

Dissociative Experiences Scale-II

The Dissociative Experiences Scale-II (DES-II)Citation33 is a 28-item self-report measure of psychological dissociation that is designed to be used as a screening instrument for dissociative disorders and to help determine the contribution of dissociation to psychiatric disorders. It has demonstrated good psychometric properties, such as adequate split–half reliability and test–retest reliability, as well as good convergent and discriminant validity. The Italian translation (Schimmenti et al, unpublished data)of the DES-II showed good internal consistency, good test–retest reliability, and good convergent validity in a mixed clinical and non-clinical sample. The Cronbach’s α coefficient of the DES-II in this study was 0.85.

Data analyses

In order to investigate the underlying dimensional structure of the scale, exploratory principal axis factor analyses with promax rotation were performed on the whole sample. With our 22-item scale, we were able to satisfy the minimum ten participants-per-item ratio that is usually recommended for factor analysis.Citation34 Prior to exploratory factor analysis, data were inspected to ensure items were significantly correlated, using Bartlett’s test of sphericity, and that they shared sufficient variance to justify factor extraction, using the Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin (KMO) measure of sampling adequacy. Sampling adequacy values that are less than 0.50 are considered unacceptable, values that are between 0.50 and 0.60 are considered marginally acceptable, and values greater than 0.80 and 0.90 are considered excellent.Citation35 Both Kaiser’sCitation36 criterion and the Scree testCitation37 were used to set the number of factors. Salience was detected applying the three following item-retention criteria to the rotated structure matrix: (1) a factor loading of at least 0.30 on the primary factor, ensuring a high degree of association between the item and the factor; (2) a difference of 0.30 between the loading on the primary factor and the loading on other factors; (3) a minimum of three items for each factor, ensuring meaningful interpretation of stable factors.Citation38

Internal consistencies of the subscales were calculated using Cronbach’s α coefficients. Corrected item–scale correlations were examined for each of the instrument subscales, ensuring that adjusted item–total correlations for each item exceeded 0.30, which is recommended for supporting scale–internal consistency.Citation39 In order to investigate the extent to which factor scores were correlated, we used the Pearson correlation coefficient. Different domains were expected to not be very highly correlated, as an indication that the subscales measured different aspects of the impact of event.

A confirmatory factor analysis, using maximum likelihood robust estimation procedures, was performed using the EQS Structural Equation Program Version 6.1.Citation40 Both orthogonal and oblique factor models were tested. The Satorra–Bentler chi-square (S–B χ2) was not used as an evaluation of absolute fit because of its sensitivity to sample size. To test the model, each variable was allowed to load on only one factor, and one variable loading in each factor was fixed at 1.0. The remaining factor loadings, residual variances, and correlations among latent factors were freely estimated. To statistically evaluate the adequacy of the hypothetical model to the empirical data, multiple goodness-of-fit indices were used: the ratio of the chi-square to degrees of freedom (χ2/df), the non-normed ft index (NNFI), the comparative fit index (CFI), the standardized root mean square residual (SRMR), and the root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA).

Results

Exploratory factor analysis

Bartlett’s test of sphericity (χ2 = 2,358.218; df = 231) was significant (P < 0.001), and the KMO measure of sampling adequacy was 0.913, indicating that the constructing questionnaire items were appropriate for a factor analysis.

The Kaiser–Guttman criterion and the inspection of the scree plot suggested extracting three factors. The factor correlation matrix, indicating a prominent inter-correlation among factor scales, supported the use of the oblique rotation procedures (promax criterion). Based on the resultant pattern matrix, items 4 and 7, which failed to load on none of the three factors, were not retained. Items 2, 10, 15, and 19, loading on two factors, were also not retained. Item 5 was removed based on its communality value of less than 0.20.

Retained items produced consistent and satisfactory loadings on a single dimension, meeting minimum requirements for inclusion. Items and factor loadings of the scale are shown in . Intercorrelations between subscale scores were r = 0.569 (P < 0.01) between hyper-arousal and avoidance; r = 0.651 (P < 0.01) between hyper-arousal and intrusion; r = 0.493 (P < 0.01) between intrusion and avoidance. As expected, the dimensions showed a significant level of correlation with each other, indicating that the questionnaire subscales measured several approaches of the impact of event that are relatively distinct from one another, suggesting an acceptable level of score independence. All subscale α coefficients can be considered as good (hyper-arousal, α = 0.83; avoidance, α = 0.72; intrusion, α = 0.78).

Table 1 Factor loadings of the scale items (pattern matrix)

Confirmatory factor analysis

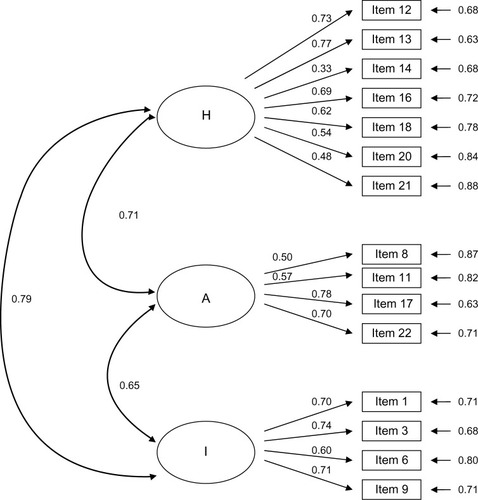

The feasibility of the three-factor oblique model that emerged from exploratory factor analysis was examined as compared with a three-factor orthogonal model. The three-factor oblique solution provided a significantly better fit to the data than did the three-factor orthogonal model. As presented in , the performed confirmatory factor analyses clearly supported the three-factor oblique solution, with the three scales as latent variables and seven items as indicators for the first latent variable, four items as indicators for the second latent variable and four items for the third: χ2(84, N = 262) = 95.80; P = 0.178; χ2/df = 1.14.

Table 2 Confirmatory factor analysis fit indexes for the oblique bi-factorial model

The fit indices met the criteria for adequacy of fit for the model, suggesting reasonable goodness of fit for the hypothesized factor structure (NNFI = 0.99; CFI = 0.99; SRMR = 0.04; RMSEA = 0.02; 90% confidence interval = 0.000–0.043) (see ).

All manifest variables loaded significantly (P < 0.05) on their hypothesized latent factors. presents the standardized parameter estimates. The three-factor model was judged to be an adequate explanation of the data. This suggests that the instrument comprises three uni-dimensional subscales.

Convergent validity

To evaluate some aspects of convergent validity of the Italian IES-R, Pearson correlations were calculated between the IES-R and the total score of the DES-II (intrusion, r = 0.32, P < 0.001; avoidance, r = 0.32, P < 0.001; hyper-arousal r = 0.28, P < 0.001).

Discussion

Given that the use of measures for assessing traumatic experiences has become more important, the aim of this work was to verify the psychometric properties of the IES-R (factor structure, reliability, and validity) in the Italian context. The IES-R is one of the most widely used measures for assessing the dimensions of trauma, with good psychometric properties. In the present research, the Italian version of the IES-R showed a clear factor structure with three independent and robust dimensions: intrusion, avoidance, hyper-arousal. Despite the fact that each dimension showed good values of internal consistency, some items did not show good factor loadings. Indeed the following items did not seem to fit well in the proposed solution: item 2 “I had trouble staying asleep”; item 4 “I felt irritable and angry”; item 5 “I avoided letting myself get upset when I thought about it or was reminded of it”; item 7 “I felt as if it hadn’t happened or wasn’t real”; item 10 “I was jumpy and easily startled”; item 15 “I had trouble falling asleep”. This could be partially due to the nature of the sample and could depend on the factor analysis criteria. The data of our study suggest the necessity of further studies in order to verify some aspects of the validity (predictive and discriminant) of the IES-R. However, the present investigation showed that this self-report instrument for assessing the dimensions of trauma has good psychometric properties and can be adopted usefully, both for research and in practice in Italy.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- American Psychiatric AssociationDiagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders5th editionWashington, DCAmerican Psychiatric Association2013

- CraparoG[Posttraumatic stress disorder]. Il Disturbo Post-Traumatico da StressRomaCarocci2013

- LillyMMPierceHPTSD and depressive symptoms in 911 telecommunicators: the role of peritraumatic distress and world assumptions in predicting riskPsychol Trauma201352135141

- RutterLAWeatherillRPKrillSCOrazemRTaftCTPosttraumatic stress disorder symptoms, depressive symptoms, exercise, and health in college studentsPsychol Trauma2013515661

- CraparoGInternet addiction, dissociation, and alexithymiaProcedia Soc Behav Sci20113010511056

- FranzoniEGualandiSCarettiVThe relationship between alexithymia, shame, trauma, and body image disorders: investigation over a large clinical sampleNeuropsychiatr Dis Treat2013918519323550168

- HorowitzMWilnerNAlvarezWImpact of Event Scale: a measure of subjective stressPsychosom Med197941209218472086

- JosephSPsychometric evaluation of Horowitz’s Impact of Event Scale: a reviewJ Trauma Stress20001310111310761177

- SundinECHorowitzMJHorowitz’s impact of event scale evaluation of 20 years of usePsychosom Med20036587087614508034

- SundinECHorowitzMJImpact of Event Scale: psychometric propertiesBr J Psychiatry200218020520911872511

- Echevarria-GuaniloMEDantasRAFarinaJAJrAlonsoJRajmilLRossiLAReliability and validity of the Impact of Event Scale (IES): version for Brazilian burn victimsJ Clin Nurs20112011–121588159721453295

- AghanwaHSWalkeyFHTaylorAJThe psychometric cross-cultural validation of the Impact of Event ScalePac Health Dialog2003102667018181418

- JohnPBRussellPSValidation of a measure to assess post-traumatic stress disorder: a Sinhalese version of Impact of Event ScaleClin Pract Epidemiol Ment Health20073417306023

- ChenSCLaiYHLiaoCTLinCCPsychometric testing of the Impact of Event Scale-Chinese Version (IES-C) in oral cancer patients in TaiwanSupport Care Cancer200513748549215717159

- van der PloegEMoorenTTKleberRJvan der VeldenPGBromDConstruct validation of the Dutch version of the impact of event scalePsychol Assess2004161162615023089

- PietrantonioFDe GennaroLDi PaoloMCSolanoLThe Impact of Event Scale: validation of an Italian versionJ Psychosom Res200355438939314507552

- HendrixCCJurichAPSchummWRValidation of the Impact of Event Scale on a sample of American Vietnam veteransPsychol Rep1994751 Pt 13213227984745

- WeissDSMarmarCRThe impact of event scale – revisedWilsonJPKeaneTMAssessing Psychological Trauma and PTSDNew YorkGuilford Press1997399411

- BáguenaMJVillarroyaEBeleñaÁAmeliaDRoldánCReigRPropiedades psicométricas de la versión Española de la Escala Revisada de Impacto del Estressor (EIE-R) [Psychometric properties of the Spanish version of the Impact of Event Scale – Revised (IES-R)]Análisis y Modificación de Conducta200127114581604

- BrunetASt-HilaireAJehelLKingSValidation of a French version of the Impact of Event Scale-RevisedCan J Psychiatry200348566112635566

- WuKKChanKSThe development of the Chinese version of Impact of Event Scale – Revised (CIES-R)Soc Psychiatry Epidemiol20033829498

- AsukaiNKatoHKawamuraNReliability and validity of the Japanese-Language version of the Impact of Event Scale-Revised (IES-R-J): four studies of different traumatic eventsJ Nerv Mental Dis20021903175182

- SveenJLowADyster-AasJEkseliusLWillebrandMGerdinBValidation of a Swedish version of the Impact of Event Scale-Revised (IES-R) in patients with burnsJ Anxiety Disord201024661862220434306

- LimHKWooJMKimTSReliability and validity of the Korean version of the Impact of Event Scale-RevisedCompr Psychiatry200950438539019486738

- BeckJGGrantDMReadJPThe Impact of Event Scale – Revised: psychometric properties in a sample of motor vehicle accident survivorsJ Anxiety Disord200822218719817369016

- KingDWOrazemRJLauterbachDKingLAHebenstreitCLShalevAYFactor structure of posttraumatic stress disorder as measured by the impact of event scale-revised: stability across cultures and timePsychol Trauma200913173187

- MannaGFaraciPComoMRFactorial structure and psychometric properties of the Sensation Seeking Scale – Form V (SSS–V) in a sample of Italian adolescentsEJOP201392276288

- TriscariMTFaraciPD’AngeloVUrsoV[Fear of flying: factorial structure of two questionnaires]. Paura di volare: struttura fattoriale di due questionariPsicoterapia Cognitiva e Comportamentale2011172211226

- FaraciPTriscariMTD’AngeloVUrsoVFear of flying assessment: a contribution to the Italian validation of two self-report measuresRev Psychol201118291100

- FaraciPLJI – Leadership Judgement IndicatorFirenzeGiunti O.S. Organizzazioni Speciali2011

- GoriAGianniniMSocciSAssessing social anxiety disorder: psychometric properties of the Italian Social Phobia Inventory (I-SPIN)Clin Neuropsychiatry20131013742

- LucaMGianniniMGoriALittletonHMeasuring dysmorphic concern in Italy: psychometric properties of the Italian Body Image Concern Inventory (I-BICI)Body Image2011830130521664200

- CarlsonEBPutnamFWAn update on the dissociative experiences scaleDissociation199361627

- GorsuchRLFactor AnalysisHillsdale (NJ)Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Inc1983

- HairJFAndersonRETathamRLBlackWCMultivariate Data Analysis4th editionNew JerseyPrentice-Hall, Inc1985

- KaiserHFA note on Guttman’s Lower Bound for the number of common factorsBr J Math Stat Psychol196114112

- CattellRBThe scree test for the number of factorsMultivar Behav Res196612245276

- TabachnickBGFidellLSUsing Multivariate Statistics3rd editionNew YorkHarper Collins1996

- DeVellisRFScale Development: Theory and Applications2nd editionThousand Oaks (CA)Sage Publications, Inc2003

- BentlerPMEQS 6 Structural Equations Program ManualEncino (CA)Multivariate Software2006