Abstract

Background

The purpose of this study was to examine the effect of sleep deprivation on flow experience.

Methods

Sixteen healthy male volunteers of mean age 21.4±1.59 (21–24) years participated in two experimental conditions, ie, sleep-deprivation and normal sleep. In the sleep-deprived condition, participants stayed awake at home for 36 hours (from 8 am until 10 pm the next day) beginning on the day prior to an experimental day. In both conditions, participants carried out a simple reaction time (psychomotor vigilance) task and responded to a questionnaire measuring flow experience and mood status.

Results

Flow experience was reduced after one night of total sleep deprivation. Sleep loss also decreased positive mood, increased negative mood, and decreased psychomotor performance.

Conclusion

Sleep deprivation has a strong impact on mental and behavioral states associated with the maintenance of flow, namely subjective well-being.

Introduction

“Flow” is a positive emotional state that typically occurs when a person perceives a balance between challenges associated with a situation and his or her capabilities to accomplish or meet the demands of this situation.Citation1 Experiencing flow commonly accompanies a feeling of immersion in various types of tasks, including those in such disparate areas as medical operation, rock climbing, and musical performance.Citation1 At work, flow is often defined by characteristics such as absorption, job satisfaction, and intrinsic/autotelic motivation.Citation2 Although the flow experience was originally investigated in highly skilled professionals, a short period of flow (or “microflow”) can occur in daily activities, such as during Internet use,Citation3 driving,Citation4 musical performance,Citation5 and sports.Citation6,Citation7 Importantly, it has been reported that the frequency of flow experiences is negatively correlated with self-disgust and guilt,Citation8 but positively correlated with subjective well-being.Citation9 Thus, flow should be considered an important factor in our quality of life.

We have previously found that sleepiness is significantly and negatively correlated with flow experience.Citation10 In our study, flow levels improved significantly following a short nap and exposure to bright light, which were applied as countermeasures against afternoon drowsiness.Citation10 The results of our previous research suggest that attenuation of sleepiness may be essential in order to experience flow (ie, flow is experienced more prevalently in states of low sleepiness); if this is the case, then people in a sleep-deprived state or in a state of high sleepiness should experience less flow when compared with individuals experiencing little drowsiness. Despite the importance of degree of sleepiness as a background state to elicit flow experience, the effect of sleep deprivation on flow experience has not been the subject of much research.

Although a direct link between sleep deprivation and flow has not been reported, previous studies suggest that sleepiness may have some negative associations with flow experience. According to the cognitive energy model proposed by Zohar et al,Citation11,Citation12 sleep deprivation reduces “cognitive energy,” which is related to emotion elicited through goal-disrupting as well as goal-enhancing events. In this model, sleep loss increases the negative affect induced by goal-disrupting events and also serves to reduce the positive affect induced by goal-enhancing events.Citation12 The cognitive energy model seems to fit well with flow theory, given that challenging tasks require a high level of cognitive energy and should induce a stronger flow experience. Therefore, it appears that a reduced level of cognitive energy, due to sleep deprivation, should also reduce flow experience.

Alternatively, it could be argued that sleep deprivation may increase flow experience during a task. It is well known that total sleep deprivation impairs cognitive performance, eg, task-switching ability.Citation13,Citation14 This, in turn, could elicit a stronger focus on a current task to compensate for the decreased cognitive ability due to sleep loss, eg, as a coping strategy with limited cognitive resources. This type of strong focus in the current task could be accompanied by a subjective status of being more intensively engaged in the task and it may be regarded as an increase in flow experience. The primary purpose of the present study is thus to confirm the effect of sleep deprivation on flow experience and cognitive performance.

We used a psychomotor vigilance task known to be sensitive to sleep deprivationCitation15–Citation17 to confirm the effect of sleep deprivation on cognitive performance. Simple tasks, such as psychomotor vigilance tasks, that are easy to learn and not heavily affected by motivation, have been identified as being appropriate for measuring the effects of sleep loss.Citation16

It has been reported that sleep deprivation not only increases sleepiness but also accelerates deterioration of mood.Citation16,Citation18,Citation19 Sleep disturbance has been cited as a precursor to a number of psychiatric conditions, including depression,Citation20 post-traumatic stress disorder,Citation21 and panic disorder.Citation22 These psychiatric problems may prevent people from engaging in challenging tasks due to a shortage of cognitive energy and low flow experience. Therefore, we used a questionnaire (ie, the Profile of Mood StatusCitation23) to measure mood status, including flow experience.

The present study used short-term sleep deprivation (for 36 hours) to investigate the acute effect of sleep deprivation on flow experience. Successive sleep deprivation of more than 36 hours has often been employed to investigate the acute effects of sleep loss in sleep studies.Citation24–Citation27 According to Durmer and Dinges,Citation27 sleep deprivation studies can be generally categorized into three types, ie, long-term total sleep deprivation (>45 hours), short-term total sleep deprivation (≤45 hours), and partial sleep deprivation (sleep restriction to <7 hours in 24 hours).Citation27

Several specific but contrasting hypotheses emerge from this prior research and are examined in the present study. These hypotheses propose that a night of total sleep deprivation would cause: lower positive and higher negative mood; decreased or increased flow experience; deterioration of psychomotor vigilance; flow to be positively correlated with psychomotor vigilance; and flow to be negatively correlated with sleepiness and fatigue and positively correlated with vitality. The present study is a part of a larger experiment designed to investigate the effect of sleep deprivation on memory. Further results will be presented elsewhere.

Materials and methods

Participants

Nineteen male university students were recruited for the present study. Three were excluded from the analysis because they could not stay awake for 36 hours. Thus, data for 16 healthy male volunteers of mean (± standard deviation) age 21.4±1.59 (21–24) years were analyzed. Only male participants were recruited because one of the memory tasks in the experiment was designed for male participants (these results will be presented elsewhere), and no sex-related difference in flow experience has been reported.Citation1 All participants met the following criteria: no current physical or mental health problems; no use of medication; no tobacco use; no night shift work within 3 months prior to the experiment; and no travel to a different time zone within the previous 3 months.

Procedure

Participants were subjected to two experimental conditions, ie, sleep-deprivation and normal sleep. The study was conducted using a within-subject crossover design in which the condition order was counterbalanced across participants (ie, eight participants started with the sleep-deprived condition and the other eight with the normal sleep condition). In the sleep-deprived condition, participants stayed awake at home for 36 hours (from 8 am until 10 pm the next day), starting on the day before the experimental day. In the normal sleep condition, participants were instructed to get a typical night’s sleep (about 7.5 hours). Participants participated in both study conditions with an interval of at least 7 days between one condition and another to prevent a carryover sleep deprivation effect. Sleep deprivation was confirmed by measuring physical activity levels with actigraphy (Actiwatch 2, Philips Respironics, Murrysville, PA, USA). Sleep durations over the course of the experiment were recorded in a sleep diary.

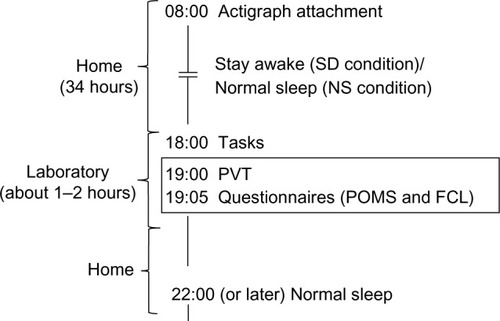

In both conditions (sleep-deprivation and normal sleep), the participants followed the same schedule/experimental procedure except for the 36 hours of sleep deprivation in the sleep-deprived condition. In both conditions, participants arrived in the laboratory at 6 pm, carried out performance tasks (including a memory task), completed questionnaires measuring flow experience and moods, and then went home to sleep. The psychomotor vigilance task and questionnaires were completed at 7 pm and 7.05 pm, respectively. The task procedures were identical under both the sleep-deprived and normal sleep conditions except for the manipulation of sleep deprivation; therefore, they should have little influence on comparisons between the two conditions. The experimental schedule is shown in .

Figure 1 Time schedule of the experiment.

Participants were asked to abstain from food and beverages containing caffeine and alcohol from 6 pm on both the experimental day and the day before the experiment (ie, the participants underwent sleep deprivation without consuming caffeine). Toxicologic screening, however, was not conducted.

The experimental protocol was reviewed and approved by the ethics committee for research involving humans at the National Institute of Advanced Industrial Science and Technology, Japan, according to the principles expressed in the Declaration of Helsinki.

Actigraphy and sleep diary

Times for going to sleep, waking up, and total sleep duration were calculated automatically by Actiware version 5.71.0 software (Philips Respironics Inc). Visual inspections were performed to confirm that the automatic analysis was properly calculated. In addition to automatic analysis, manual inspection of the actigraphy data was also done to count the number of “immobile periods” during sleep deprivation at home. The definition of immobile periods was arbitrarily set at more than 15 minutes after several inspections of the data.

Flow checklist

The Flow Checklist, originally developed in Japanese by Ishimura,Citation28 was used. The Flow Checklist consists of ten items (each rated on a seven-point Likert scale ranging from 1= “does not apply at all” to 7= “highly applicable”) that are categorized as three independent factors, ie, “confidence in competence”, “rise to a challenge”, and “positive emotion and absorption”. Each factor consists of two to four items: “everything is going well”, “I am able to control situations”, “I am confident in managing matters”, and “I am in control of my behavior/movements” for the first factor (ie, confidence); “I feel my work is challenging” and “I am making progress toward reaching my goals” for the second factor (ie, challenge); “I feel time flies”, “I am in a state of complete concentration”, “I am completely immersed”, and “I am enjoying my work” for the third factor (ie, immersion). The Flow Checklist questions concerning the performance task, were carried out before the ratings, and the reliability of the Flow Checklist has been confirmed in an earlier study. Participants were asked to circle the number best representing their present feelings on the seven-point scale.

Profile of mood status

The Japanese version of the Profile of Mood StatusCitation23 was used to assess current mood. The participants expressed their mood status on a 100 mm visual analog scale, with separate dimensions for “anxious”, “sleepy”, “fatigued”, “apathetic”, “confused”, “angry”, and “sad” on the right end of the line and “not anxious”, “not sleepy”, “not fatigued”, “vigorous”, “not confused”, “not angry”, and “not sad” on the left end of the line. Participants were asked to view the lines as representing their personal range of feelings and to place a mark on the line indicating their feeling at the moment.

Psychomotor vigilance test

The psychomotor vigilance testCitation29 (PVT) uses a simple visual reaction time paradigm with interstimulus intervals ranging from 2 to 10 seconds. Participants have to detect a stimulus and respond using a button on a keyboard as quickly as possible. The stimulus (a small counter increasing in milliseconds) is displayed in the center of a computer screen. The PVT used in the present study was the 5-minute version.Citation30 Median reaction times and lapses (times more than 500 msec) were calculated.

Data analysis

Paired t-tests were used to compare the sleep-deprived and normal sleep conditions. The Wilcoxon signed-rank test (nonparametric test, n=16) was also applied. Significance levels were set at P<0.05. All statistical analyses were conducted using Statistical Package for the Social Sciences version 22.0 software (IBM, Armonk, NY, USA).

Results

Actigraphy and sleep diary data

Sleep deprivation was confirmed by sleep diary and actigraphy data. Total sleep time on the day preceding the experiment was also calculated from the actigraphy data. The results indicate no significant difference between the conditions [371.5±97.67 minutes in the sleep deprivation condition; 434.37±126.12 minutes in the normal sleep condition; t(15)=1.67, effect size (d)=0.40, P=0.12]. Total sleep time on the night before the experiment in the normal sleep condition was 457.2±124.40 minutes. Sleep efficiency was 98.7% (calculated by dividing total sleep time in the actigraphy data by time in bed recorded in the sleep diary). Times of going to sleep and waking (actigraphy data) were 1.59±101.42 minutes and 9.36±148.77 minutes, respectively. This “night owl” sleep schedule may have been due to the flexible time schedule typical of university students.

We also calculated the number of periods of immobility using the actigraphy data. This was done using only 15 data sets because data from one of the subjects could not be analyzed due to technical problems with one of the recording devices. From this inspection, six immobile periods were detected in four participants. The cumulative immobile periods for the four participants were 42, 44, 82, and 122 minutes (mean 48.3±18.42 minutes) over 36 hours. Although our results show that the participants did not undergo total sleep deprivation in the strict sense (ie, absolutely no sleep at all), they were still in a condition of “severe sleep loss”, which would be sufficient to examine the effects of sleep loss on flow experience.

Flow experience

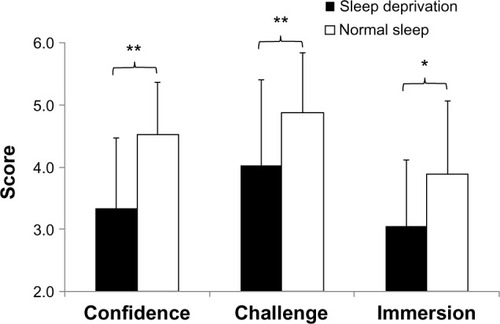

Flow experience along all three dimensions decreased in the sleep-deprived condition as compared with the normal sleep condition [confidence, t(15)=3.70, d=0.69, P<0.01, Wilcoxon’s T (T) =2.84, P<0.01; challenge, t(15)=3.18, d=0.64, P<0.01, T=2.72, P<0.01; and immersion, t(15)=2.30, d=0.51, P<0.05, T=2.05, P<0.05], as shown in .

Profile of mood status

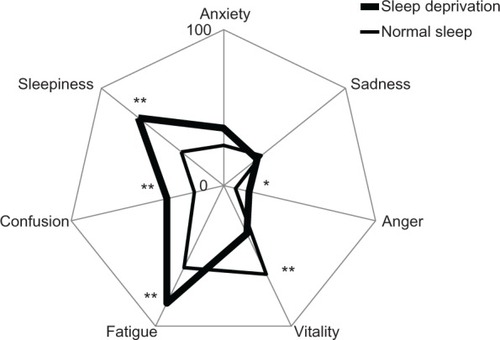

Mood status deteriorated after sleep loss, except for the anxiety and sadness dimensions, as shown in . Sleepiness, confusion, and fatigue scores were higher in the sleep-deprived condition than in the normal sleep condition [sleepiness, t(15)=4.14, d=0.73, P<0.01, T=2.98, P<0.01; confusion, t(15)=2.92, d=0.60, P<0.01, T=2.35, P<0.05; fatigue, t(15)=3.79, d=0.70, P<0.01, T=3.00, P<0.01; and anger, t(15)=2.07, d=0.47, P<0.05, T=1.62, P<0.10]. Vitality was lower in the sleep-deprived condition [t(15)=3.90, d=0.71, P<0.01, T=2.79, P<0.01]. There were no significant differences for anxiety and sadness [anxiety, t(15)=1.49, d=0.36, P=0.07, T=1.39, P=0.16; sadness, t(15)=0.35, d=0.09, P=0.72, T=0.36, P=0.71].

Psychomotor vigilance test

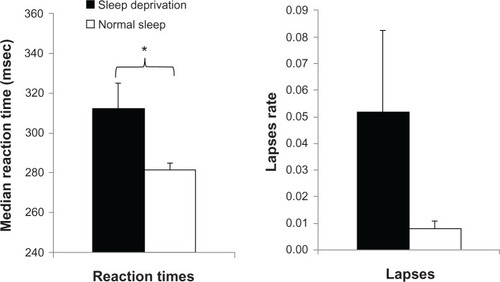

Median reaction times were significantly longer in the sleep-deprived condition compared with the normal sleep condition [t(15)=2.09, d=0.48, P<0.05, T=3.05, P<0.01], which means that psychomotor vigilance deteriorated after a night of sleep loss, as shown in . There was no significant difference in lapse rates between the two conditions [t(15)=1.40, d=0.34, P=0.18, T=1.62, P=0.10], as shown in .

Correlation analysis

As shown in , all three factors of flow were significantly and positively correlated with vitality (r=0.45 to 0.57), and negatively correlated with fatigue (r=−0.43 to −0.68) and sleepiness (r=−0.38 to −0.55). However, none of the three factors of flow showed any significant correlations with PVT indices (median reaction time and lapses). Median PVT was significantly and positively correlated with fatigue (r=0.35) and sleepiness (r=0.37). Median PVT and lapses were strongly correlated with each other (r=0.91).

Table 1 Pearson’s product-moment correlation coefficient (r)

Discussion

The present study reveals that all aspects of flow experience (confidence, challenge, and immersion) decrease after sleep deprivation. In addition, flow indices were significantly and negatively correlated with fatigue (r=−0.43 to −0.68) and sleepiness (r=−0.38 to −0.55). These results suggest that sleep/sleepiness is an important factor in flow experience, and maintaining a low level of sleepiness is essential in order to induce flow. To the best of our knowledge, the relationship between sleep loss and flow experience has not been previously examined.

Consistent with previous studies, positive mood (vitality) was reduced and negative mood (sleepiness, fatigue, confusion, anger) was increased after sleep deprivation.Citation19,Citation31–Citation34 Importantly, this study found that flow experience and vitality were positively related (r=0.45 to 0.57). The results support our assumption based on the cognitive energy modelCitation11,Citation12 that lower levels of cognitive energy, due to sleep deprivation, reduce the motivation to engage in challenging tasks and hence impede flow experience. This is consistent with another report in which sleep deprivation was found to impede concentration and creative thinking.Citation35

In the present study, confusion and anxiety ratings increased after sleep loss, although the result for anxiety did not reach statistical significance (P=0.07). These results are consistent with previous studies reporting that 36 hours of prolonged wakefulness increases self-reported anxiety on the State-Trait Anxiety Inventory questionnaire.Citation36 It has been reported that panic attacks are more likely to occur in insomniacs,Citation22 and this may be related to deterioration in mood due to sleep loss.

There were no significant correlations between flow indices and PVT performances. This suggests that flow may not influence basic cognitive ability as reflected in simple reaction skills. The present study used PVT because it is sensitive to sleep loss. A number of other performance tasks have been developed and tested to evaluate the effect of sleep loss; these include the Stroop task,Citation16 switching task,Citation13 visual search task,Citation37 and a working memory task.Citation38 However, these tasks are less associated with sleep deprivation than with PVT,Citation39 because they involve higher order cognitive skills that show a learning effect; in addition, people performing these tasks are susceptible to motivation to perform at a higher level than normal.Citation16 Higher order cognitive skills, however, may be associated to a greater degree with flow experience compared with simple skills because flow features more prominently in complicated tasks that require a higher skill level. Flow could occur when we combine different types of skills rather than when we perform a simple task such as detecting a target. The neurobehavioral science of flow experience has not as yet been the subject of investigation.

The present study employed a rather severe schedule of sleep deprivation, yet previous studies have employed a similar experimental design. The next step in this type of investigation should consider practical situations, such as partial or chronic sleep deprivation and sleep fragmentation. It is known that deterioration of psychomotor ability corresponds to the amount of sleep loss accumulated through consecutive nights of short sleep periods.Citation24 It would be interesting to explore whether partial and/or accumulation of sleep loss has an influence on flow. This line of investigation would be more applicable to real-life settings, such as in occupational health (eg, shift work and aging) and medicine (eg, sleep apnea syndrome and periodic leg movements). Further, this topic is better suited to epidemiologic studies of longitudinal design because laboratory experiments cannot eliminate bias based on an individual’s presumptions due to the nature of the experimental design (ie, the aim of the study is likely to be obvious to participants).

A shortcoming of the present study is its lack of separation of effects due to sleep loss itself from those due to stress caused by sleep deprivation. Flow experience may be affected not only by sleep loss per se (ie, an arousal factor) but also by psychologic stress (ie, emotional factors). Further research should examine the separate effects of these factors. In addition, only young male participants took part in the present study. The potential effects of differences in sex and age on the effects of sleep loss on flow should also be investigated.

In conclusion, the present study confirms that flow experience is reduced after one night of total sleep deprivation. In addition, sleep loss decreased positive mood, increased negative mood, and caused deterioration in the performance of a vigilance task. These results suggest that sleep deprivation has a strong impact on the mental and behavioral states involved in maintenance of subjective well-being.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by JSPS KAKENHI (25705022).

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- CsikszentmihalyiMFlow: The Psychology of Optimal ExperienceNew York, NYHarper and Row1990

- DemeroutiEJob characteristics, flow, and performance: the moderating role of conscientiousnessJ Occup Health Psychol20061126628016834474

- PilkeEMFlow experiences in information technology useInt J Hum Comput Stud200461347357

- KawasakiMKaidaKKishiHWatanabeNYamadaHYamaguchYHuman theta and alpha EEG oscillations estimate the delight and satisfaction under improvements of driving skillsNingen Kogaku201046307316 Japanese

- BakkerABFlow among music teachers and their students: the crossover of peak experiencesJ Vocat Behav2005662644

- BakkerABOerlemansWDemeroutiESlotBBAliDKFlow and performance: a study among talented Dutch soccer playersPsychol Sport Exerc201112442450

- JacksonSAFordSKKimiecikJCMarshHWPsychological correlates of flow in sportJ Sport Exerc Psychol199820358378

- HiraoKKobayashiRThe relationship between self-disgust, guilt, and flow experience among Japanese undergraduatesNeuropsychiatr Dis Treat2013998598823898226

- SalanovaMBakkerABLlorensSFlow at work: evidence for an upward spiral of personal and organizational resourcesJ Happiness Stud20067122

- KaidaKTakedaYTsuzukiKThe relationship between flow, sleepiness and cognitive performance: the effects of short afternoon nap and bright light exposureInd Health20125018919622453206

- ZoharDTzischinskiOEpsteinREffects of energy availability on immediate and delayed emotional reactions to work eventsJ Appl Psychol2003881082109314640818

- ZoharDTzischinskyOEpsteinRLaviePThe effects of sleep loss on medical residents’ emotional reactions to work events: a cognitive-energy modelSleep200528475415700720

- HeuerHKleinsorgeTKleinWKohlischOTotal sleep deprivation increases the costs of shifting between simple cognitive tasksActa Psychol (Amst)2004117296415288228

- CouyoumdjianASdoiaSTempestaDThe effects of sleep and sleep deprivation on task-switching performanceJ Sleep Res2010191 Pt 1647019878450

- JewettMEDijkDJKronauerREDingesDFDose-response relationship between sleep duration and human psychomotor vigilance and subjective alertnessSleep19992217117910201061

- DingesDFPackFWilliamsKCumulative sleepiness, mood disturbance, and psychomotor vigilance performance decrements during a week of sleep restricted to 4–5 hours per nightSleep1997202672779231952

- DrummondSPBischoff-GretheADingesDFAyalonLMednickSCMeloyMJThe neural basis of the psychomotor vigilance taskSleep2005281059106816268374

- FranzenPLSiegleGJBuysseDJRelationships between affect, vigilance, and sleepiness following sleep deprivationJ Sleep Res200817344118275553

- BaglioniCSpiegelhalderKLombardoCRiemannDSleep and emotions: a focus on insomniaSleep Med Rev20101422723820137989

- VollrathMWickiWAngstJThe Zurich study. VIII. Insomnia: association with depression, anxiety, somatic syndromes, and course of insomniaEur Arch Psychiatry Neurol Sci19892391131242806334

- HarveyAGJonesCSchmidtDASleep and posttraumatic stress disorder: a reviewClin Psychol Rev20032337740712729678

- NaHRKangEHYuBHRelationship between personality and insomnia in panic disorder patientsPsychiatry Investig20118102106

- McNairDMLorrMDropplemanLFManual for the Profile of Mood StatesSan Diego, CAEducational and Industrial Testing Services1971

- Van DongenHPMaislinGMullingtonJMDingesDFThe cumulative cost of additional wakefulness: dose-response effects on neurobehavioral functions and sleep physiology from chronic sleep restriction and total sleep deprivationSleep20032611712612683469

- HorneJAPettittANHigh incentive effects on vigilance performance during 72 hours of total sleep deprivationActa Psychol (Amst)1985581231393984776

- GouldKSHirvonenKKoefoedVFEffects of 60 hours of total sleep deprivation on two methods of high-speed ship navigationErgonomics2009521469148619941181

- DurmerJSDingesDFNeurocognitive consequences of sleep deprivationSemin Neurol20052511712915798944

- IshimuraIPsychological Study on Enhancing Factors and Positive Functions of Flow Experiences. Doctoral thesisTsukuba, JapanSchool of Comprehensive Human Sciences, Tsukuba University2008

- DingesDPowellJMicrocomputer analysis of performance on a portable, simple visual RT task during sustained operationsBehav Res Methods Instrum Comput198517652655

- RoachGDDawsonDLamondNCan a shorter psychomotor vigilance task be used as a reasonable substitute for the ten-minute psychomotor vigilance task?Chronobiol Int20062361379138717190720

- BrendelDHReynoldsCF3rdJenningsJRSleep stage physiology, mood, and vigilance responses to total sleep deprivation in healthy 80-year-olds and 20-year-oldsPsychophysiology1990276776852100353

- MikulincerMBabkoffHCaspyTSingHThe effects of 72 hours of sleep loss on psychological variablesBr J Psychol198980Pt 21451622736337

- PilcherJJHuffcuttAIEffects of sleep deprivation on performance: a meta-analysisSleep1996193183268776790

- HaackMMullingtonJMSustained sleep restriction reduces emotional and physical well-beingPain2005119566416297554

- HorneJASleep loss and “divergent” thinking abilitySleep1988115285363238256

- SagaspePSanchez-OrtunoMCharlesAEffects of sleep deprivation on Color-Word, Emotional, and Specific Stroop interference and on self-reported anxietyBrain Cogn200660768716314019

- KaidaKTakedaYTsuzukiKCan a short nap and bright light function as implicit learning and visual search enhancers?Ergonomics2012551340134922928470

- FuldaSSchulzHCognitive dysfunction in sleep disordersSleep Med Rev2001542344512531152

- TuckerAMWhitneyPBelenkyGHinsonJMVan DongenHPEffects of sleep deprivation on dissociated components of executive functioningSleep201033475720120620