Abstract

Transdermal rotigotine (RTG) is a non-ergot dopamine agonist (D3>D2>D1), and is indicated for use in early and advanced Parkinson’s disease (PD). RTG patch has many potential advantages due to the immediacy of onset of the therapeutic effect. Of note, intestinal absorption is not necessary and drug delivery is constant, thereby avoiding drug peaks and helping patient compliance. In turn, transdermal RTG seems a suitable candidate in the treatment of atypical Parkinsonian disorders (APS).

Fifty-one subjects with a diagnosis of APS were treated with transdermal RTG. The diagnoses were: Parkinson’s disease with dementia, multiple system atrophy Parkinsonian type, multiple system atrophy cerebellar type, progressive supranuclear palsy, corticobasal degeneration, Lewy body dementia, and frontotemporal dementia with Parkinsonism. Patients were evaluated by the Unified Parkinson’s Disease Rating Scale (UPDRS; part III), Neuropsychiatric Inventory (NPI), and mini–mental state examination (MMSE) and all adverse events (AEs) were recorded. Patients treated with RTG showed an overall decrease of UPDRS III scores without increasing behavioral disturbances. Main AEs were hypotension, nausea, vomiting, drowsiness, tachycardia, and dystonia. On the whole, 15 patients were affected by AEs and seven patients suspended RTG treatment due to AEs.

The results show that transdermal RTG is effective with a good tolerability profile. RTG patch could be a good therapeutic tool in patients with APS.

Introduction

Atypical Parkinsonian disorders (APS) are a group of diseases that share extrapyramidal features with Parkinson’s disease (PD), but with a globally different clinical picture and different neuropathological substrates. The most recognized APS are: progressive supranuclear palsy (PSP), corticobasal degeneration (CBD), multiple system atrophy (MSA), Parkinson’s disease with dementia (PDD), and Lewy body dementia (LBD). PSP, CBD, MSA, PDD, and LBD are distinct pathological entities.Citation1–Citation5 The pathophysiology of APS is still unknown and the therapeutic choices are very limited. For example, the major limitation to the use of dopaminergic agents in APS is the high risk of inducing psychotic adverse events (AEs) and behavioral disturbances.Citation6,Citation7

Recently, a novel agent has been approved for PD: transdermal rotigotine (RTG). RTG is a non-ergolinic dopamine agonist (DA) administered via a transdermal patch that delivers the drug over a 24-hour period.Citation8 The RTG transdermal patch is available in various dosages (ie, 2–8 mg).

The application of the RTG transdermal patch provides predictable release and absorption of RTG. A lot of recent well-designed and large clinical trials have demonstrated that RTG produces significant improvements in the Unified Parkinson’s Disease Rating Scale (UPDRS) summed motor and activities of daily living (ADL) scores as compared to placebo.Citation9–Citation14 Moreover, transdermal RTG has been demonstratedCitation9 to improve motor functioning, sleep disturbances, nighttime motor symptoms, pain and functioning, and depressive symptoms. On the whole, RTG was well-tolerated across the trials.Citation10–Citation15 Thus, the RTG transdermal patch offers a useful therapeutic tool for the treatment of motor and non-motor symptoms in extrapyramidal disorders like APS.

In most of the clinical trials carried out so far, transdermal RTG has been administered only in patients with idiopathic PD. In the present study, RTG was administered to 51 patients with APS, showing overall good performance on motor symptoms without inducing behavioral or psychiatric disorders usually seen when dopaminergic agonists are used in patients with cognitive disorders associated with extrapyramidal features.

Methods

Subjects

Fifty-one subjects admitted to the memory clinic of the National Institute for Research and Cure of Neurodegenerative Disorders Fatebenefratelli (FBF) in Brescia, Italy were diagnosed as having APS. Transdermal RTG was administered to all 51 patients. Subjects were evaluated by board-certified neurologists and movement disorder specialists who work in the Memory Clinic and Movement Disorders Center. All experimental protocols were approved by the local ethics committee. Informed consent was obtained from all participants or their caregivers, according to the Code of Ethics of the World Medical Association (Declaration of Helsinki). shows sociodemographic data for the whole study group.

Table 1 Sociodemographical data of the whole study group

Diagnostic criteria

In our subjects, diagnoses were as follows: PDD (nine patients), MSA-Parkinsonism (MSA-P; eleven), MSA-cerebellar type (MSA-C; four), PSP (seven), CBD (ten), LBD (nine), and frontotemporal dementia with parkinsonism (FTD-P; one). In this study, the subjects affected by PSP were all the PSP-Parkinsonism (PSP-P) type. Moreover, all diagnoses were performed exclusively on clinical evaluation. Subjects were titrated with transdermal RTG to the minimal effective dosage ().

Table 2 Number of subjects and clinical characteristics at baseline, T6, T12, and T18 follow-up

Diagnostic criteria of APS were inferred from literature guidelines determined by the most influential previous studies and largely accepted clinical evidence.Citation16–Citation23 Briefly, the main clinical features of the classical PSP phenotype are postural instability, early falls, early cognitive decline with frontal symptoms, and abnormalities of vertical gaze; this is known as Richardson’s syndrome (RS). PSP has been subdivided into two main clinical and pathological phenotypes: classical RS and PSP-P. PSP-P differs from the classical form because of an asymmetric onset, tremor, and a mild-to-moderate early therapeutic response to levodopa.Citation2,Citation24 As regards to CBD, the classical clinical picture consists of asymmetric Parkinsonism and cortical signs (eg, apraxia, cortical sensory loss, and alien limb). Dystonia and myoclonus can be part of the syndrome. It is usually defined as corticobasal syndrome (CBS) when there is not a neuropathological confirmation. MSA is helpfully recognized by the presence of Parkinsonism, autonomic dysfunction, and mixed cerebellar and pyramidal signs. MSA is, in turn subdivided into MSA-P or MSA-C type based on the predominant phenotype at onset. In this study, patients who developed dementia more than 1 year after the onset of clinically definite PD were included. The diagnosis of clinically definite PD was based on previously published criteria: the presence of at least two of the three cardinal signs of akinesia, rigidity, and resting tremor. Other criteria required were unilateral onset and the development of postural instability associated with significant responsiveness to a dopaminergic agent.Citation25–Citation28 According to the clinical guidelines of LBD diagnosis, patients with cognitive impairment developed less than 1 year from the appearance of Parkinsonian symptoms, repeated falls, hallucinations at disease onset, or symptom fluctuations, and vivid dreams were included in this group.Citation29,Citation30 The main concomitant pathologies of the patients in the study sample were: hypertension, hypercholesterolemia, hypertensive cardiopathy, type 2 diabetes mellitus, and carotid atheroma. As a consequence, patients were taking antihypertensive, antiplatelet, and antidiabetic drugs. The patients were encouraged to maintain the concomitant treatments as stably as possible. Patients who presented psychosis were not admitted to the study. No other anti-Parkinsonian agents were taken by the patients before or during the study. Memory, visuospatial skills, and language were the most affected cognitive domains.

Clinical evaluation

All patients underwent complete physical and neurological examinations. All patients underwent an electroencephalographic (EEG) and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). Only 27 patients underwent single photon emission computed tomography dopamine transporter scan (SPECT-daT scan). MRI is useful for excluding vascular Parkinsonism, whereas SPECT shows diffuse and more symmetric degeneration of nigrostriatal pathways, as well as excluding idiopathic PD, which usually has a clearly asymmetric impairment. Patients were evaluated with the Unified Parkinson’s disease rating scale (UPDRS) part III (out of a total of 56 points),Citation31 Neuropsychiatric Inventory (NPI),Citation32 and the mini–mental state examination (MMSE)Citation33 at baseline and after 6, 12, 18 months of follow-up (T0, T6, T12, T18). All AEs were recorded.

Statistical analysis

The Kolmogorov–Smirnov test was applied to check the distribution of the sample population. The result was P=0.76, thus confirming the normal distribution of the sample. One-way analysis of variance (ANOVA), with Newman–Keuls post-hoc correction, was performed to test the changes in the MMSE, UPDRS-III, and NPI, at all time points (T0, T6, T12, T18). Post-hoc test analysis was performed only when the main analysis had a significant result (P<0.05) in order to explore which of the single comparisons were statistically significance. Age and education were considered to be covariates in the main ANOVA.

Results

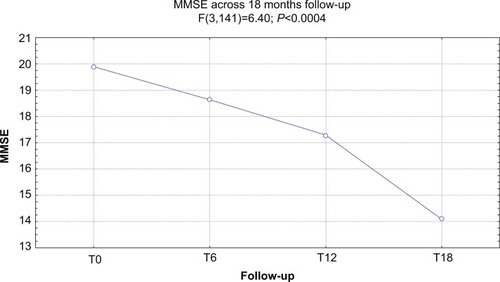

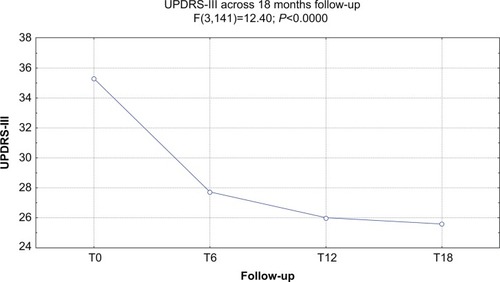

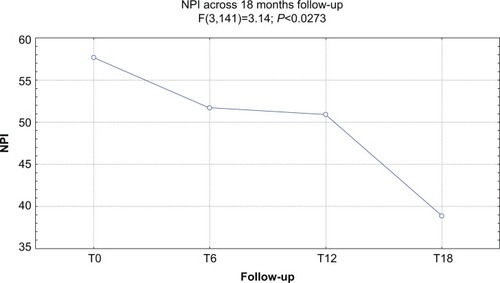

At baseline, the mean UPDRS-III score was 35.2/56, the mean NPI score was 57.6/144, and the mean MMSE score was 19.9/30. Forty-five of 51 (88.2%) patients completed 6 months of treatment with RTG (mean dose =3.24 mg/24 hours): the mean UPDRS-III score was 28.1/56, the mean NPI score was 52.1/144, and the mean MMSE score was 18.9/30. Six patients dropped out due to AEs. Thirty of 51 (58.8%) patients completed 12 months of treatment with RTG (mean dose =4.2 mg/24 hours): the mean UPDRS-III score was 26.4/56, the mean NPI score was 51.5/144, and the mean MMSE score was 17.2/30. One more patient dropped out due to AEs. Twenty-one of 51 (41.1%) patients completed 18 months of treatment with RTG (mean dose =5.1 mg/24 hours): the mean UPDRS-III score was 25.5/56, the mean NPI score was 38.8/144, and the mean MMSE score was 14.1/30. No patients dropped out at the 18-month follow-up. Reported AEs were: hypotension (13 patients), nausea (ten), vomiting (four), drowsiness (four), tachycardia (two), dystonia (three patients with anterocollis, all treated with concomitant L-3,4-dihydroxyphenylalanine). On the whole, 15 patients were affected by AEs (29.4%) and seven patients suspended RTG treatment due to AEs (13.7%; vomiting, tachycardia, and sleepiness). No heart congestion failure was detected among our patients.

The subscore of the NPI scale regarding delusions and hallucinations was examined. At baseline, the mean scores were 2/12 for delusion and 1.5/12 for hallucinations. These scores remained invariate at T6 and T12, and did not change statistically significantly at T18 (1.8/12 and 1.3/12, respectively).

shows the ANOVA results for UPDRS. A significant decrease of the score (P<0.00005) was found. After post-hoc analysis, all comparisons with the baseline were statistically significant (P<0.0002).

Figure 1 ANOVA results for UPDRS score.

shows the ANOVA results for NPI. A significant decrease of the score (P<0.003) was found. After post-hoc analysis, all comparisons with the T18 follow-up were statistically significant (P<0.004).

Figure 2 ANOVA results for NPI score.

shows the ANOVA results for MMSE. A significant decrease of the score (P<0.0004) was found. After post-hoc analysis, all comparisons with the T18 follow-up were statistically significant (P<0.02).

Discussion

Current treatment options in APS

Recently there has been growing attention in trying to identify a possible therapy for sporadic APS conditions. The monoamine oxidase-B inhibitor rasagiline (1 mg/day) was administered for 48 weeks in 174 patients with possible or probable MSA-P type, in a randomized, placebo-controlled clinical trial. No significant differences were found in the total Unified Multiple System Atrophy Rating Scale (UMSARS) score between the treatment and placebo groups.Citation34 Infusions of 0.4 g/kg intravenous immunoglobulin for 6 months were administered in a single-arm, single-center, open-label pilot trial in seven patients. In this trial, a significant improvement was found in UMSARS part I (ADL) and II (motor functions).Citation35 Thirty-three patients with probable MSA-C type were treated with 30–50 intra-arterial or intravenous injections of autologous mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) and compared with placebo. The results demonstrated that the MSC group had an increase in total and part II UMSARS scores from baseline after a 360-day follow-up period.Citation36

As regards to PSP, 313 participants were treated with 30 mg davunetide or placebo twice daily for 52 weeks in a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. No significant effects were found on the Progressive Supranuclear Palsy Rating Scale (PSPRS) and the Schwab and England Activities of Daily Living (SEAD; see on http//www.fiercebiotech.com/press-release/allon-announces-psp-clinical-trials-results, press release by Allon Therapeutics on December 18, 2012). Inhibitors of glycogen synthase kinase-3 (GSK-3), were also administered in patients with APS. One hundred and forty-two patients with PSP were treated orally with tideglusib (600 mg or 800 mg per day), in a Phase II, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial or placebo for 1 year. There were no significant differences between the high dose and low dose, as well as between the drug versus the placebo groups in the outcome measures.Citation37,Citation38 Finally, an open-label pilot trial of lithium, also an inhibitor of GSK-3, in 17 patients both with PSP and CBD (ClinicalTrials.gov identifier NCT00703677) was stopped prematurely because of the presence of severe AEs.

Transdermal RTG as a treatment option for APS

Transdermal RTG seems to be effective and well-tolerated in patients with APS. Our results show significant improvement in UDPRS-III scores, maintained along the course of the 18 months’ follow-up. Moreover, only seven patients dropped out, out of the 15 patients affected by AEs. These results confirm previous evidence obtained in patients with idiopathic PD showing positive effect on motor control.Citation10–Citation15 A plausible explanation of the results is that transdermal RTG provides continuous dopaminergic stimulation, reducing the unwanted motor effects of immediate release dopaminergic therapies. Our results also show a reduction of NPI scores, which became significant at the last follow-up evaluation (T18), confirming previous evidence in PD studies. According to these studies, RTG patients have absolute reductions in off-time that are similar to those reported in comparable studies with the oral DAs pramipexole or ropinirole. The clinical relevance of the observed improvement in off-time and on motor functions is further supported by a significant improvement in the quality of life, as seen in the mobility, ADL, and emotional well-being domains of the Parkinson’s Disease Questionnaire (PDQ)-39. The AE profiles of both active treatments in this study were similar. Typical dopaminergic side effects were seen, and both drugs were well-tolerated. There were small differences in the frequency of dopaminergic side effects with RTG and pramipexole: there were more reports of nausea in patients receiving RTG than in those on pramipexole; by contrast, patients on pramipexole reported hallucinations, dyskinesias, and dizziness more frequently than did patients receiving RTG.

Although efficacy and systemic tolerability were similar for transdermal RTG and oral pramipexole and ropinirole, transdermal drug delivery could still offer several important benefits for the treatment of patients with Parkinsonian symptoms. One of these is related to dosing via once daily patch administration, which could potentially enhance compliance, particularly in patients on regimens with several oral drugs (eg, in patients with motor fluctuations, where the daily tablet intake is often above ten). Nonadherence to prescribed medication has been identified as a major problem in APS patients, both with respect to missed doses and mistiming of scheduled doses, which has an obvious effect on the quality of control of motor oscillations. Another potential advantage of transdermal drug delivery in PD is related to the lack of drug–food interactions with such delivery systems. Such a delivery system could be advantageous in clinical settings with patients experiencing impaired swallowing, which is common in patients with APS.Citation39,Citation40 Of note, it has been demonstrated that the administration of RTG in patients with poor morning motor control reduces the morning motor symptoms, sleep disturbances, and other non-motor symptoms.Citation12–Citation14 Patients with extrapyramidal symptoms are particularly prone to the side effects of anti-Parkinsonian dopaminergic therapy, such as symptoms of depression and anxiety, hallucinations, delusions (with prevalent paranoid symptoms), agitation, and delirium.Citation41,Citation42 Furthermore, treatment with DAs is the main risk factor for developing impulse control disorders (ICDs). The most common ICDs reported with other DAs like ropinirole, pramipexole, bromocriptine, as well as the ergot-DA, are pathological gambling, hypersexuality, and compulsive shopping and eating.Citation6–Citation8 Our study did not find behavioral or psychiatric AEs nor ICDs. This could be explained by the particular pharmacological action of RTG, which is different from other dopaminergic agents. At first, RTG has its highest affinity for D3 receptors,Citation43 whereas other dopaminergic agents share their main action on both D2/D3 receptors. D3 is localized in the caudate–putamen region, with particular concentrations in the ventral striatum. This peculiar position seems to be of a crucial importance in modulating the affective state.Citation43 Another important difference with other DAs is that transdermal RTG also has high activity at non-dopaminergic receptors, in particular the α2B-adrenergic receptors and the serotonin 5-HT1A receptors, which could positively modulate mood and behavior. The duration of the therapeutic effect on other motor and behavioral symptoms for up to 18 months of follow-up could suggest a neuroprotective effect. Although previously seen in animal models and in vitro studies,Citation43,Citation44 this aspect needs to be cautiously assessed further. During our study, none of the patients suffered from congestive heart failure. In this aspect, the low affinity of RTG for 5-hydroxytryptamine receptor 2B (5-HT2B) may be of clinical importance. All other ergolinic DAs provoking cardiac valvular damage are full or partial 5-HT2B receptor agonists.Citation45

The MMSE score shows that patients were highly cognitively impaired, on average, at the beginning of the study. Our results show no positive effect on cognitive status. However, further studies with less initially cognitively compromised patients grouped for single pathologies will better clarify this issue.

Conclusion

RTG appears to be a suitable therapy in elderly patients as it has a good tolerability profile, improves patients’ compliance, and helps management of fragile patients. D3 receptor activation in the caudate–putamen region by RTG compensates for hypodopaminergic function in pathways in these areas and is probably responsible for the efficacy of this drug.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- LitvanIBhatiaKPBurnDJMovement Disorders Society Scientific Issues CommitteeMovement Disorders Society Scientific Issues Committee report: SIC Task Force appraisal of clinical diagnostic criteria for Parkinsonian disordersMov Disord200318546748612722160

- WilliamsDRde SilvaRPaviourDCCharacteristics of two distinct clinical phenotypes in pathologically proven progressive supranuclear palsy: Richardson’s syndrome and PSP-parkinsonismBrain2005128Pt 61247125815788542

- GilmanSWenningGKLowPASecond consensus statement on the diagnosis of multiple system atrophyNeurology200871967067618725592

- WenningGKGeserFKrismerFEuropean Multiple System Atrophy Study GroupThe natural history of multiple system atrophy: a prospective European cohort studyLancet Neurol201312326427423391524

- StamelouMQuinnNPBhatiaK“Atypical” atypical parkinsonism: new genetic conditions presenting with features of progressive supra-nuclear palsy, corticobasal degeneration, or multiple system atrophy-a diagnostic guideMov Disord20132891184119923720239

- AntoniniACiliaRBehavioural adverse effects of dopaminergic treatments in Parkinson’s disease: incidence, neurobiological basis, management and preventionDrug Saf200932647548819459715

- VilasDPont-SunyerCTolosaEImpulse control disorders in Parkinson’s diseaseParkinsonism Relat Disord201218Suppl 1S80S8422166463

- SchnitzlerALeffersKWHäckHJHigh compliance with rotigotine transdermal patch in the treatment of idiopathic Parkinson’s diseaseParkinsonism Relat Disord2010161851351620605106

- TrenkwalderCKiesBRudzinskaMRecover Study GroupRotigotine effects on early morning motor function and sleep in Parkinson’s disease: a double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled study (RECOVER)Mov Disord2011261909921322021

- BaldwinCMKeatingGMRotigotine transdermal patch: a review of its use in the management of Parkinson’s diseaseCNS Drugs200721121039105518020483

- PoeweWHRascolOQuinnNSP 515 InvestigatorsEfficacy of pramipexole and transdermal rotigotine in advanced Parkinson’s disease: a double-blind, double-dummy, randomised controlled trialLancet Neurol20076651352017509486

- SanfordMScottLJRotigotine transdermal patch: a review of its use in the treatment of Parkinson’s diseaseCNS Drugs201125869971921790211

- LeWittPABoroojerdiBSurmannEPoeweWSP716 Study Group; SP715 Study GroupRotigotine transdermal system for long-term treatment of patients with advanced Parkinson’s disease: results of two open-label extension studies, CLEOPATRA-PD and PREFERJ Neural Transm201312071069108123208198

- Ray ChaudhuriKMartinez-MartinPAntoniniARotigotine and specific non-motor symptoms of Parkinson’s disease: post hoc analysis of RECOVERParkinsonism Relat Disord201319766066523557594

- ZhouCQLiSSChenZMLiFQLeiPPengGGRotigotine transdermal patch in Parkinson’s disease: a systematic review and meta-analysisPLoS One201387e6973823936090

- WenningGKBen-ShlomoYMagalhãesMDanielSEQuinnNPClinicopathological study of 35 cases of multiple system atrophyJ Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry19955821601667876845

- WenningGKTisonFBen ShlomoYDanielSEQuinnNPMultiple system atrophy: a review of 203 pathologically proven casesMov Disord19971221331479087971

- WenningGKScherflerCGranataRTime course of symptomatic orthostatic hypotension and urinary incontinence in patients with postmortem confirmed parkinsonian syndromes: a clinicopathological studyJ Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry199967562062310519868

- WenningGKStefanovaNJellingerKAPoeweWSchlossmacherMGMultiple system atrophy: a primary oligodendrogliopathyAnn Neurol200864323924618825660

- LitvanIMangoneCAMcKeeANatural history of progressive supranuclear palsy (Steele-Richardson-Olszewski syndrome) and clinical predictors of survival: a clinicopathological studyJ Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry19966066156208648326

- LitvanIAgidYCalneDClinical research criteria for the diagnosis of progressive supranuclear palsy (Steele-Richardson-Olszewski syndrome): report of the NINDS-SPSP international workshopNeurology1996471198710059

- WilliamsDRLeesAJProgressive supranuclear palsy: clinicopathological concepts and diagnostic challengesLancet Neurol20098327027919233037

- LingHO’SullivanSSHoltonJLDoes corticobasal degeneration exist? A clinicopathological re-evaluationBrain2010133Pt 72045205720584946

- LiscicRMSrulijesKGrögerAMaetzlerWBergDDifferentiation of progressive supranuclear palsy: clinical, imaging and laboratory toolsActa Neurol Scand2013127536237023406296

- LarsenJPDupontETandbergEThe clinical diagnosis of Parkinson’s disease. Proposal of diagnostic subgroups classified at different levels of confidenceActa Neurol Scand19948942422518042440

- AarslandDLitvanISalmonDGalaskoDWentzel-LarsenTLarsenJPPerformance on the dementia rating scale in Parkinson’s disease with dementia and dementia with Lewy bodies: comparison with progressive supranuclear palsy and Alzheimer’s diseaseJ Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry20037491215122012933921

- BerardelliAWenningGKAntoniniAEFNS/MDS-ES/ENS [corrected] recommendations for the diagnosis of Parkinson’s diseaseEur J Neurol20132011634 Erratum in: Eur J Neurol. 2013; 20(2):40623279440

- StamelouMHoeglingerGUAtypical parkinsonism: an updateCurr Opin Neurol201326440140523812308

- McKeithIGGalaskoDKosakaKConsensus guidelines for the clinical diagnosis of dementia with Lewy bodies (DLB): report of the consortium on DLB international workshopNeurology1996475111311248909416

- McKeithIGDicksonDWLoweJet al; Consortium onDLBDiagnosis and management of dementia with Lewy bodies: third report of the DLB ConsortiumNeurology200565121863187216237129

- FahnSEltonRLUPDRS Program MembersUnified Parkinson’s disease rating scaleFahnSMarsdenCDGoldsteinMCalneDBRecent Developments in Parkinson’s Disease2Florham Park, NJMacmillan Healthcare Information1987153163293304

- CummingsJLMegaMGrayKRosenberg-ThomsonSCarusiDAGornbeinJThe Neuropsychiatric Inventory: comprehensive assessment of psychopathology in dementiaNeurology19944412230823147991117

- FolsteinMFFolsteinSEMcHughPR“Mini-mental state”. A practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinicianJ Psychiatr Res1975123189981202204

- PoeweWBaronePGliadiNA randomized, placebo-controlled clinical trial to assess the effects of rasagiline in patients with multiple system atrophy of the parkinsonian subtypeMov Disord201227Suppl 1 abstr 1182

- NovakPWilliamsARavinPZurkiyaOAbduljalilANovakVTreatment of multiple system atrophy using intravenous immunoglobulinBMC Neurol20121213123116538

- LeePHLeeJEKimHSA randomized trial of mesenchymal stem cells in multiple system atrophyAnn Neurol2012721324022829267

- HöglingerGUHuppertzHJWagenpfeilSTAUROS MRI InvestigatorsTideglusib reduces progression of brain atrophy in progressive supranuclear palsy in a randomized trialMov Disord201429447948724488721

- StamelouMde SilvaRArias-CarriónORational therapeutic approaches to progressive supranuclear palsyBrain2010133Pt 61578159020472654

- LiebermanAOlanowCWSethiKA multicenter trial of ropinirole as adjunct treatment for Parkinson’s disease. Ropinirole Study GroupNeurology1998514105710629781529

- LiebermanARanhoskyAKortsDClinical evaluation of pramipexole in advanced Parkinson’s disease: results of a double-blind, placebo-controlled, parallel-group studyNeurology19974911621689222185

- LeWittPALyonsKEPahwaRSP 650 Study GroupAdvanced Parkinson disease treated with rotigotine transdermal system: PREFER studyNeurology200768161262126717438216

- GeorgievDDanieliAOcepekLOthello syndrome in patients with Parkinson’s diseasePsychiatr Danub2010221949820305599

- SchellerDUllmerCBerkelsRGwarekMLübbertHThe in vitro receptor profile of rotigotine: a new agent for the treatment of Parkinson’s diseaseNaunyn Schmiedebergs Arch Pharmacol20093791738618704368

- SchellerDStichel-GunkelCLübbertHNeuroprotective effects of rotigotine in the acute MPTP-lesioned mouse model of Parkinson’s diseaseNeurosci Lett2008432130418162314

- ZanettiniRAntoniniAGattoGGentileRTeseiSPezzoliGValvular heart disease and the use of dopamine agonists for Parkinson’s diseaseN Engl J Med20073561394617202454