Abstract

Background

Alcohol abuse and dependence can cause a wide variety of cognitive, psychomotor, and visual-spatial deficits. It is questionable whether this condition is associated with impairments in the recognition of affective and/or emotional information. Such impairments may promote deficits in social cognition and, consequently, in the adaptation and interaction of alcohol abusers with their social environment. The aim of this systematic review was to systematize the literature on alcoholics’ recognition of basic facial expressions in terms of the following outcome variables: accuracy, emotional intensity, and latency time.

Methods

A systematic literature search in the PsycINFO, PubMed, and SciELO electronic databases, with no restrictions regarding publication year, was employed as the study methodology.

Results

The findings of some studies indicate that alcoholics have greater impairment in facial expression recognition tasks, while others could not differentiate the clinical group from controls. However, there was a trend toward greater deficits in alcoholics. Alcoholics displayed less accuracy in recognition of sadness and disgust and required greater emotional intensity to judge facial expressions corresponding to fear and anger.

Conclusion

The current study was only able to identify trends in the chosen outcome variables. Future studies that aim to provide more precise evidence for the potential influence of alcohol on social cognition are needed.

Introduction

It is well known that alcoholism can lead, in the long-term, to deficits in neurocognitive functions that involve memory, learning, visual-spatial orientation, psychometricity, and information processing, among other skills.Citation1,Citation2 In addition, previous authors have highlighted pronounced impairments in the recognition of affective and/or emotional information.

Such impairments promote deficits in social cognition and, consequently, in the adaptation and interaction of alcohol abusers with their social environment.Citation3–Citation6 These deficits occur because social cognition is one of the key aspects of emotional adaptive functioning. It is also an important nonverbal social skill that conveys messages about individuals’ emotional states at the moment of interaction, thus providing clues that aid the interpretation of behaviors.Citation7

These deficits, together with the development of interpersonal problems, could become risk factors for the maintenance of an individual’s cycle of alcohol abuse and/or dependence. They may induce relapses to drinking and hinder the processes of withdrawal, treatment, and recovery.Citation8–Citation10

Given this situation, the majority of studies in the area that have aimed to verify and/or measure the presence of such deficits have employed tasks that involve recognition of basic facial expressions, such as anger, disgust, fear, and sadness (negative emotions), and happiness and surprise (positive emotions). These studies have primarily assessed one or more of the following three key variables: accuracy, latency time, and emotional intensity, pointing to some specific changes.

In addition, smaller and more recent studies in this field have monitored brain electrical activity during the performance of cognitive tasks through the use of electroencephalogram instrumentation. These studies have shown that alcoholics exhibit lower brain activation in regions that mediate visual, auditory, and visual-motor processes and deficits in processing anger.Citation11–Citation14

Other studies have investigated the recognition of facial expressions during neuroimaging tests performed via functional magnetic resonance imaging techniques. These studies have indicated, for example, that alcoholics show lower brain activity in the cingulate, orbitofrontal, and insular cortex (regions that mediate emotional processing) during recognition of facial expressions of fearCitation15 and disgust.Citation6 In addition, Marinkovic et alCitation16 showed that alcoholic individuals have lower activation in the right amygdala and hippocampus upon negative and positive stimuli compared with nonalcoholics. These studies suggest that this deficient activation may underlie impaired processing of emotional faces in alcoholic individuals.

Considering the field of knowledge in question and the nonsystematization of findings, the present study consists of a systematic literature review of facial expression recognition by individuals with a history of alcohol abuse and dependence. This aim was achieved by reviewing clinical studies that included accuracy, latency time, and emotional intensity.

Materials and methods

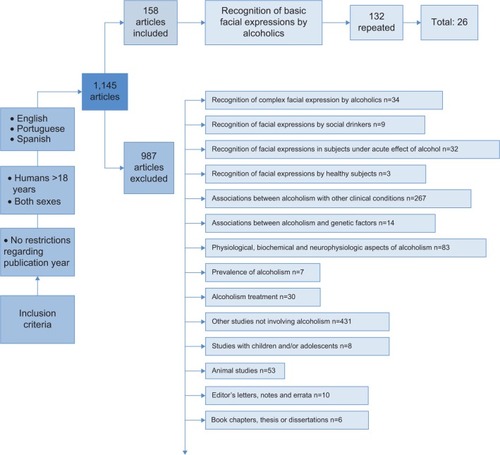

This review was conducted in accordance with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) statementCitation17 and followed the instructions in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions.Citation18 A systematic search was performed in the PsycINFO, PubMed, and SciELO electronic databases using the following keywords: (alcohol OR alcoholism OR alcoholics) AND (faces OR facial) AND (recognition OR expression OR emotional). The cut-off date for the search was February 6, 2014. The main aspects of the article inclusion and exclusion process are shown in . As observed in , a total of 1,145 articles were found. Applying the inclusion and exclusion criteria, two researchers selected 26 articles for analysis in the current review.Citation3,Citation4,Citation6,Citation7,Citation9–Citation15,Citation19–Citation33

Results

Context and samples

In general, most of the studies were conducted in Belgium (57.7%, n=15), beginning in the early 2000s (96%). Only one study had a descriptive methodological design,Citation30 with the remaining studies being of case-control design. The data are presented in , which also shows the main sociodemographic and clinical characteristics of the samples.

Table 1 Sample composition and countries of origin in the analyzed studies

The majority of the clinical subjects were alcohol-abstinent individuals who were undergoing treatment. Of these individuals, 80.8% were inpatients (n=21),Citation3,Citation4,Citation7,Citation9,Citation11–Citation15,Citation19–Citation26,Citation28,Citation31–Citation33 and 7.7% were outpatients (n=2).Citation10,Citation29 The samples ranged from eight to 52 subjects (mean 22.9 and median 24), with mean ages between 35.7 and 60.8 years (median 44.7 years) and varying education levels. Prior consumption of alcohol ranged from 12.8 to 39.1 (mean 19) drinks per day. Periods without alcohol consumption generally ranged from 1–8 (median 3) weeks. In two of the studies, this variability was greater, reaching up to 21 years.Citation19,Citation27

In terms of the control group, 88.5% of the studies (n=23) selected healthy subjects with no history of alcohol use from the general population. Social drinkers were used as the control group in only two studies, and their alcohol consumption was 3.3–13 drinks per week.Citation4,Citation7 The control group sample sizes ranged from ten to 47 subjects (mean 23 and median 24), with ages ranging from 33.7 to 45.5 years (median 43.8 years) and variable education levels.

Most studies diagnosed alcohol abuse and/or dependence according to the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-IV; n=25), with the exception of one study that used the DSM-III-R.Citation9 All subjects abstained from alcohol. Furthermore, only one study utilized the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis I disorder.Citation32 The controls were primarily healthy subjects from the general population without a prior history of alcohol dependence (n=23). Exclusion criteria for both groups were as follows: presence of comorbidity with any Axis I psychiatric disorder (n=17);Citation3,Citation4,Citation9–Citation12,Citation14,Citation20,Citation22,Citation25–Citation28,Citation30–Citation33 presence of comorbidity with any Axis II psychiatric disorder (n=1);Citation33 visual or hearing impairment (n=8);Citation4,Citation11–Citation14,Citation24–Citation26 epilepsy (n=9);Citation11–Citation14,Citation24–Citation27,Citation32 health problems in general (n=8);Citation4,Citation7,Citation12,Citation14,Citation24,Citation25,Citation27,Citation32 intellectual impairment (n=4);Citation3,Citation9,Citation20,Citation27 Wernicke-Korsakoff syndrome (n=2);Citation26,Citation27 and use of medications (n=2).Citation21,Citation32 Five studies did not present their exclusion criteria.Citation6,Citation15,Citation23,Citation28,Citation29

Facial expression recognition tasks: stimuli and procedures

The main aspects related to types of stimuli and the procedures that the studies used to perform facial expression recognition tasks (FERT) are summarized in , which shows that the studies used a wide variety of stimuli and procedures. However, this diversity does not seem to have influenced the outcomes, as discussed below.

Table 2 Main characteristics of stimuli and procedures used for FERT

Outcome variables

The main results according to the outcome variables analyzed in the studies are listed in . The results concerning accuracy were highly divergent. Of the 23 studies that analyzed accuracy, 17 (73.9%) found at least some difference between the groups, indicating impairment in alcoholic individuals with regard to correctly identifying disgust (26%) and sadness (26%). However, 16 studies found no differences between the groups, indicating no impairment in alcoholic individuals with regard to identifying emotions, especially anger (43.7%). In addition, ten studies (43.5%) that evaluated accuracy found differing results for the same sample group. Specifically, alcoholics showed greater impairment in recognizing some emotions but not others. The findings were generally contradictory.

Table 3 Results according to the outcome variables analyzed

Of the eight studies that evaluated the emotional intensity needed for emotion recognition, at least six found a difference in specific emotions. The group of alcoholics required higher intensities for emotion recognition, particularly for fear (50%) and anger (37.5%). However, in seven of these studies this difference was not observed, especially with regard to happiness (75%).

Finally, of the eleven studies that evaluated latency time, five (45.5%) found that alcoholics required more time for emotion recognition. These results were more evident when the total score of emotions was evaluated. A small number of studies analyzed specific emotions, and the results were contradictory.

All of the results presented were also analyzed while taking into account the different variables associated with the stimuli and procedures used in FERT, ie, the methods chosen for data collection. Despite the great diversity of employed methodologies, none of them seemed to have clearly interfered with the results. In other words, no particular result was associated with any specific stimulus and/or procedure.

The influence of sociodemographic features, particularly the influence of male/female sex on FERT performance, was also evaluated. Of the four studies that analyzed this variable,Citation9,Citation10,Citation23,Citation27 only the study of Frigerio et alCitation10 found significant differences. This study indicated that women needed less emotional intensity than men to recognize facial expressions, regardless of whether they had a history of alcoholism.

Only the study by Kornreich et alCitation19 evaluated the influence of duration of alcohol abstinence on FERT performance. This study found that alcoholics who abstained from alcohol for a longer period of time required a lower intensity to judge the emotion compared with recently detoxified alcoholics; however, there was no improvement in accuracy. In addition, only the study by Foisy et alCitation23 evaluated the difference between a group of abstinent subjects undergoing treatment and a group of subjects who discontinued alcohol detoxification due to relapses. This study showed that the latter had lower accuracy, but no difference was observed in the emotional intensity required for recognition.

Discussion

The present study aimed to systematize the literature on recognition of basic facial expressions by alcoholic subjects in terms of the following outcome variables: accuracy, emotional intensity, and latency time. One noteworthy finding is that these studies were conducted recently and were primarily developed by European researchers, with a group of researchers from Belgium being responsible for 57.7% of the studies (n=15).

Homogeneity in the group of researchers who have studied the topic and the significantly diverse methodologies used across studies could have considerably influenced the results. However, despite the great variability of stimuli and procedures in the reviewed studies, a qualitative initial analysis indicated that these variables did not have a direct influence on the studied outcomes. Specifically, different results did not display a direct relationship with any of these variables.

None of the studies included subjects in the clinical groups who were consuming alcohol at the time of measurement. Therefore, future studies in this population are necessary. It is also noteworthy that a small number of subjects were examined in both the clinical groups (8–52) and the control groups (10–47). Thus, the use of larger sample sizes is suggested for future studies.

The prior literature has suggested that respondent characteristics have a direct influence on FERT. Thus, the stimuli that compose FERT and respondent characteristics should be considered separately. Namely, the following variables stand out: male/female sex of the respondent, given that women recognize both positive and negative emotions more accurately and more rapidly than men;Citation34 age of the respondent, given that adults above the age of 45 years tend to wrongly identify facial stimuli more often than do younger subjects;Citation35 education level of the respondent, as individuals with lower education levels identify facial expressions of fear and disgust less accurately than individuals with higher education levels;Citation36 and type of task used, because dynamic tasks have greater ecological validity than do static tasks, given that the former involve movement and are thus more similar to the actual stimuli.Citation37–Citation39

Only four studies used an intelligence test to screen the sample, and just one study considered the presence of comorbidity with Axis II personality disorders when assessing exclusion criteria. This observation warrants attention because the literature indicates that the presence of both cognitive deficits and a specific personality disorder can negatively impact FERT performance.Citation40–Citation45 These variables are particularly important when considering alcoholics, because cognitive deficits may be associated with degeneration of specific brain areas due to chronic and excessive alcohol use.Citation40,Citation41,Citation46 The same approach is valid for personality disorders, as comorbidity rates (especially with antisocial and borderline personality disorders) are considerable, reaching levels greater than 50%.Citation43–Citation45

Some studies indicated alcoholics’ greater impairment in FERT, while others did not differentiate between their clinical and control groups. Several studies found differences in accuracyCitation2,Citation14,Citation20,Citation21,Citation23,Citation24,Citation48 between alcoholics and controls. For sadnessCitation3,Citation9,Citation10,Citation28,Citation30 and disgust,Citation3,Citation9,Citation13,Citation20,Citation30,Citation33 which are considered negative emotions, there was a slight tendency towards impairment in the group of alcoholics. The same result was observed for emotional intensity, as some studies found that alcoholics were less sensitive in FERTCitation3,Citation9 and required greater emotional intensity to judge angerCitation7,Citation9,Citation23 and fear.Citation7,Citation9,Citation26,Citation31

The justification given for such positive findings was that the chronic use of alcohol caused changes in the brain structures involved in processing visual-spatial information and the perception of, for example, nonverbal signals,Citation9,Citation20 especially with regard to negative and/or aversive emotions.Citation19,Citation28,Citation30 In addition, it has been found that alcoholics show dysfunction in the right cerebral hemisphere, which is responsible for processing negative emotions.Citation19,Citation47 Thus, some authors support the hypothesis that impairments in social cognition are consequences of deficits in the central nervous system and that they even become a reason for maintaining the vicious cycle of drinking.Citation2,Citation3,Citation9,Citation13,Citation20

Unlike the variables of accuracy and emotional intensity, studies have shown greater homogeneity for latency time. Specifically, alcoholics require more time to judge emotions as a whole.Citation11,Citation30,Citation31,Citation33–Citation35,Citation41 This difference suggests that chronic use of alcohol may impair cognitive functions, such as the speed of processing of emotional information and attention level while performing a task. Thus, alcoholics needed more time to focus on the task and complete it.Citation4,Citation12,Citation14,Citation27,Citation29 Overall, most justifications for the presence of impairments are related to neurocognitive function.Citation1,Citation2

In contrast, the hypothesis used to explain the lack of differences in the three outcome variables (accuracy, intensity, and latency time) between the groups in terms of FERT is associated with the different methodological procedures used. According to Fein et alCitation27 some paradigms may be more sensitive than others in detecting differences between groups. Studies that used simpler tasks, such as those in which the subject was offered the possibility of classifying emotions as high (70%) or low (30%) intensity or in which the subject answered “yes” or “no” as rapidly as possible after recognizing the emotion displayed,Citation15,Citation23 found no differences between groups. Conversely, studies that used more complex tasks, such as requesting the subject to classify the intensity of an emotion using a seven-point Likert scale or to choose one of four options of available emotions,Citation10,Citation19 found differences between groups. Thus, more complex tasks that require more effort from the subjects are able to demonstrate impairment, whereas simpler tasks can level all individuals and thus underestimate the possible deficits.

In addition, other hypotheses underpinning the lack of differences between groups suggest that impairments in the ability to recognize emotions may be independent of alcohol abuse. Such impairments may be associated with other factors, such as primary impairment, which is due to altered emotional intelligenceCitation21 or the genetic history of the individual. Further, this genetic history is capable of potentially leading to an increased predisposition to the development of abnormalities in the brain regions involved in emotional processing.Citation9 As an example, in the study reported by Schandler et alCitation48 preschool children from families with alcoholic individuals exhibited deficits in processing visual-spatial information.

Despite the inconclusive results, it is important to consider the judgment deficits mentioned because they may have a negative impact on the social life of the individual who abuses or is dependent on alcohol. This potential impact becomes even more relevant because the impairments related to social cognition are not restricted to the variables that were analyzed in the current study. It is also known that alcoholics have a tendency to overestimate emotionsCitation7 and show response biases toward negative emotions.Citation11,Citation12,Citation22,Citation23 Considering this set of impairments, alcoholics are more vulnerable to displaying inappropriate reactions in social situations. Thus, they may experience difficulties in interpersonal relationships and social isolation, and even become involved in fights and/or aggression, which can reduce their quality of life and reinforce their continued alcohol use.Citation8,Citation20

Conclusion

The presented data demonstrate divergent results across the relevant studies. Therefore, rather than reaching definite conclusions, only trends can be identified. The current study showed that this line of research is recent and restricted to small groups of researchers who do not use standard methodology. These inconsistencies further complicate direct comparison between studies because, as previously noted, the number of variations between the stimuli and procedures adopted is high. The systematization of a single procedure seems necessary and urgent. Researchers in this area of study should target their efforts in this direction. Most of the studies were performed in European countries, limiting potential generalizations of the findings to other sociocultural contexts. However, context is an important variable in the etiology of alcoholism.Citation49,Citation50 Attention must be paid to other critical points in the studies, such as: adoption of intellectual screening tests; ascertainment of comorbidity, particularly with personality disorders; the lack of samples arising from different sociocultural contexts; and the lack of samples comprising subjects who are currently consuming alcohol.

Future research can still delineate this field of knowledge, providing more accurate evidence on whether alcoholism influences social cognition. Nevertheless, some of the findings herein regarding the negative effect of alcohol use on the recognition of emotions have clinical implications. Such implications should be considered in both the treatment of alcoholism and the prevention of relapse, with the aim of minimizing the negative impacts of the distorted interpretation of feelings and/or emotions.Citation19,Citation27

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by Coordination for the Improvement of Higher Level Personnel and Agency of São Paulo Research Foundation (FAPESP- grant 2012/02260-7).

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- BatesMEBowdenSCBarryDNeurocognitive impairment associated with alcohol use disorders: implications for treatmentExp Clin Psychopharmacol200210319321212233981

- VieiraRMTPáduaASF[Prejuízos neurocognitivos na dependência alcoólica: um estudo de caso] Neurocognitive impairments in alcohol dependence: a case reportRev Psiquiatr Clin2007345246250 Spanish

- KornreichCBlairySPhilippotPImpaired emotional facial expression recognition in alcoholism compared with obsessive-compulsive disorder and normal controlsPsychiatr Res20011023235248

- MauragePCampanellaSPhilippotPFace processing in chronic alcoholism: a specific deficit for emotional featuresAlcohol Clin Exp Res200832460060618241315

- UekermannJDaumLSocial cognition in alcoholism: a link to prefrontal cortex dysfunction?Addiction2008103572673518412750

- O’DalyOGTrickLScaifeJWithdrawal-associated increases and decreases in functional neural connectivity associated with altered emotional regulation in alcoholismNeuropsychopharmacol2012371022672276

- TownshendJMDukaTMixed emotions: alcoholics’ impairments in the recognition of specific emotional facial expressionsNeuropsychologia200341777378212631528

- MarlattGAKosturnCFLangARProvocation of anger and opportunity for retaliation as determinants of alcohol consumption in social drinkersJ Abnorm Psychol19758466526591194526

- PhilippotPKornreichCBlairySAlcoholics’ deficits in the decoding of emotional facial expressionAlcohol Clin Exp Res19992361031103810397287

- FrigerioEBurtMDMontagneBFacial affect perception in alcoholicsPsychiatr Res20021131161171

- MauragePPhilippotPVerbanckPIs the P300 deficit in alcoholism associated with early visual impairments (P100, N170)? An oddball paradigmClin Neurophysiol2006118363364417208045

- MauragePPhilippotPJoassinFThe auditory-visual integration of anger is impaired in alcoholism: an event-related potentials studyJ Psychiatry Neurosci200733211112218330457

- MauragePCampanellaSPhilippotPElectrophysiological correlates of the disrupted processing of anger in alcoholismInt J Psychophysiol2008701506218577404

- MauragePCampanellaSPhilippotPAlcoholism leads to early perceptive alterations, independently of comorbid depressed state: an ERP studyClin Neurophysiol20083828397

- SalloumJBRamchandaniVABodukaJBlunted rostral anterior cingulate response during a simplified decoding task of negative emotional facial expressions in alcoholic patientsAlcohol Clin Exp Res20073191490150417624997

- MarinkovicKOscar-BermanMUrbanTAlcoholism and dampened temporal limbic activation to emotional facesAlcohol Clin Exp Res2009331111801192

- MoherDLiberatiATetzlaffJPreferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statementPLoS Med20096716

- HigginsJPTGreenSCochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions. Version 5.1.0The Cochrane Collaboration2011 Available from: http://www.cochrane.org/handbookAccessed July 31, 2014

- KornreichCBlairySPhilippotPDeficits in recognition of emotional facial expression are still present in alcoholics after mid- to long-term abstinenceJ Stud Alcohol200162453354211513232

- KornreichCPhilippotPFoisyMLImpaired emotional facial expression recognition is associated with interpersonal problems in alcoholismAlcohol Alcohol200237439440012107044

- KornreichCFoisyMLPhilippotPImpaired emotional facial expression recognition in alcoholics, opiate dependence subjects, methadone maintained subjects and mixed alcohol-opiate antecedents subjects compared with normal controlsPsychiatr Res20031193251260

- FoisyMLKornreichCFobeAImpaired emotional facial expression recognition in alcohol dependence: do these deficits persist with midterm abstinence?Alcohol Clin Exp Res200531340441017295724

- FoisyMLKornreichCPetiauCImpaired emotional facial expression recognition in alcoholics: are these deficits specific to emotional cues?Psychiatr Res200715013341

- MauragePCampanellaSPhilippotPThe crossmodal facilitation effect is disrupted in alcoholism: a study with emotional stimuliAlcohol Alcohol200742655255917878215

- SprahLNovakTBehavioural inhibition system (BIS) and behavioural activation system (BAS) as predictors of emotional and cognitive deficits observed in alcohol abstainersPsychiatr Danub200820218419318587289

- MauragePCampanellaSPhilippotPImpaired emotional facial expression decoding in alcoholism is also present for emotional prosody and body posturesAlcohol Alcohol200944547648519535496

- FeinGKeyKSzymanskiMDERP and RT delays in long-term abstinent alcoholics in processing of emotional facial expressions during gender and emotion categorization tasksAlcohol Clin Exp Res20103471127113920477779

- AcharyaRDolanMImpact of antisocial and psychopathic traits on emotional facial expression recognition in alcohol abusersPersonal Ment Health200162126137

- KumarSKhessCRJSinghARFacial emotion recognition in alcohol dependence syndrome: intensity effects and error patternIndian Journal of Community Psychology2011712025

- SteinmetzJPFederspielCAlcohol-related cognitive and affective impairments in a sample of long-term care residentsGeroPsych20122528395

- KornreichCBreversDCanivetDImpaired processing of emotion in music, faces and voices supports a generalized emotional decoding deficit in alcoholismAddict201210818088

- CharletKSchlagenhaufFRichterANeural activation during processing of aversive faces predicts treatment outcome in alcoholismAddict Biol201419343945123469861

- Carmona-PereraMClarkLYoungLImpaired decoding of fear and disgust predicts utilitarian moral judgment in alcohol dependent individualsAlcohol Clin Exp Res20143811724033426

- HoffmannHKesslerHEppelTExpressions intensity, gender and facial emotion recognition: women recognize only subtle facial emotions better than menActa Psychol (Amst)2010135327828320728864

- HorningSNCornwellEHaskerPThe recognition of facial expressions: an investigation of the influence of age and cognitionNeuropsychol Dev Cogn B Aging Neuropsychol Cogn201219665767622372982

- TraufferNMWidenSCRussellJAEducation and the attribution of emotion to facial expressionsMigr Teme2013222237247 Croatian

- AlvesNTRecognition of static and dynamic facial expressions: a study reviewPsicol Estud2013181125130 Spanish

- AmbadarZSchoolerJCohnJFDeciphering the enigmatic face: the importance of facial dynamics to interpreting subtle facial expressionsPsychol Sci200516540341015869701

- FiorentiniCVivianiPIs there a dynamic advantage for facial expressions?J Vis2011113115

- PfefferbaumALimKOZipurskyRBBrain grey and white matter volume loss accelerates with aging in chronic alcoholics: a quantitative MRI studyAlcohol Clin Exp Res1992166107810891471762

- ChenACPorjeszBRangaswamyMReduced frontal lobe activity in subjects with high impulsivity and alcoholismAlcohol Clin Exp Res200731115616517207114

- AdamsDOliverCThe expression and assessment of emotions and internal states in individuals with severe or profound intellectual disabilitiesClin Psychol Rev201131329330621382536

- EcheburuaEBravo De MedinaRAizpiriJAlcoholism and personality disorders: an exploratory studyAlcohol Alcohol200540432332615824064

- EcheburuaEBravo De MedinaRAizpiriJComorbidity of alcohol dependence and personality disorders: a comparative studyAlcohol Alcohol200742661862217766317

- MarchAABlairRJDeficits in facial affect recognition among antisocial populations: a meta-analysisNeurosc Biobehav Rev2008323454465

- JerminganTLButtersNDiTragliaGReduced cerebral grey matter observed in alcoholics using magnetic resonance imagingAlcohol Clin Exp Res19911534184271877728

- HutnerNOsacar-BermanMVisual laterality for the perception of emotional words in alcoholic and aging individualsJ Stud Alcohol19965721441548683963

- SchandlerSLThomasCSCohenMJSpatial learning deficits in preschool children of alcoholicsAlcohol Clin Exp Res1995194106710727485818

- PopovaSRehmJPatraJComparing alcohol consumption in central and eastern Europe to other European countriesAlcohol Alcohol200742546547317287207

- LaranjeiraRPinskyISanchesMAlcohol use patterns among Brazilian adultsRev Bras Psiquiatr201032323123219918673