Abstract

The early detection of poststroke dementia (PSD) is important for medical practitioners to customize patient treatment programs based on cognitive consequences and disease severity progression. The aim is to diagnose and detect brain degenerative disorders as early as possible to help stroke survivors obtain early treatment benefits before significant mental impairment occurs. Neuropsychological assessments are widely used to assess cognitive decline following a stroke diagnosis. This study reviews the function of the available neuropsychological assessments in the early detection of PSD, particularly vascular dementia (VaD). The review starts from cognitive impairment and dementia prevalence, followed by PSD types and the cognitive spectrum. Finally, the most usable neuropsychological assessments to detect VaD were identified. This study was performed through a PubMed and ScienceDirect database search spanning the last 10 years with the following keywords: “post-stroke”; “dementia”; “neuro-psychological”; and “assessments”. This study focuses on assessing VaD patients on the basis of their stroke risk factors and cognitive function within the first 3 months after stroke onset. The search strategy yielded 535 articles. After application of inclusion and exclusion criteria, only five articles were considered. A manual search was performed and yielded 14 articles. Twelve articles were included in the study design and seven articles were associated with early dementia detection. This review may provide a means to identify the role of neuropsychological assessments as early PSD detection tests.

Introduction

Stroke, a cerebrovascular disease (CVD), is one of the major causes of quality of life reduction through physical disabilities; the second most important risk factor for cognitive impairment and dementia, with a frequency ranging from 16%–32%; and the third cause of mortality after heart diseases and cancer.Citation1,Citation2 However, aging and possession of a specific form of gene that links mild cognitive impairment (MCI) to Alzheimer’s disease (AD) are the most common causes of significant cognitive impairment.Citation3 Poststroke dementia (PSD) includes all dementia types that may occur after stroke. Stroke survivors more prone to develop dementia, of which 20%–25% are diagnosed with vascular dementia (VaD), approximately 30% with degenerative dementia (particularly AD), and 10%–15% with a combination of AD and VaD (mixed dementia).Citation4–Citation6 Approximately 1%–4% of elderly people aged 65 years suffer from VaD, and the prevalence doubles every 5–10 years after this age.Citation5,Citation7 However, cognitive impairment and dementia following a stroke diagnosis may involve multiple functions, and the most affected domains are attention, executive function, memory, visuospatial ability, and language, as shown in .Citation1,Citation8,Citation9

Table 1 Cognition domain and function

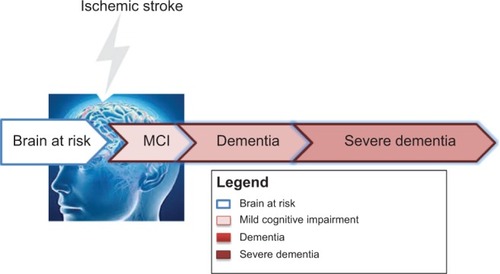

VaD is the second most common type of dementia after AD and is considered to be the primary cause of clinical deficits with burden on cognition in vascular cognitive impairment (VCI) resulting from CVD and ischemic or hemorrhagic brain injury.Citation10,Citation11 VCI describes the VaD cognitive spectrum in the cognitive domain starting from MCI and ending with severe dementia. The VCI spectrum is defined after the point where the brain’s cognitive function remains intact; at risk, this period is called cognitive impairment no dementia.Citation12–Citation15 MCI in cognitive function is greater than expected with respect to the age and education level of patients, but it is unrelated to daily life activities.Citation8,Citation14 Clinically, MCI is the transitional stage between early normal cognition and late severe dementia, and patients with MCI exhibit a high potential to develop dementia.Citation5,Citation16 The most frequently observed symptoms of MCI are limited to memory retrieval; however, the daily life activities are unaffected.Citation17 The stage after MCI, which is termed the dementia stage, will reduce long-term memory (particularly episodic memory) and will eventually result in executive function impairment.Citation18–Citation20 VaD or severe dementia is the endpoint of the VCI spectrum that affects 10% of single-attack stroke patients in the subsequent months after ischemic stroke onset and 30% after recurrent ischemic stroke.Citation21 shows the cognitive consequences that predispose stroke individuals in the VCI spectrum.

Figure 1 VCI spectrum and dementia.

Poststroke cognitive impairment patterns change considerably during the whole VCI spectrum. Thus, the cognitive defects following a stroke may be mapped by assessing the cognitive domain. However, poststroke prominent impairments are associated with one or more cognitive functions and thus require the evaluation of the decline in cognitive function, including attention, memory, language, and orientation.Citation1 The neuropsychological assessments that are currently available for cognitive impairment and dementia have been developed by the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke and Association Internationale pour la Recherché et l’Enseignement en Neurosciences (NINDS–AIREN) for VaD.Citation22 In clinical practice, the most usable test to evaluate the severity of dementia (but not limited to this condition) is to run the diagnosis based on the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition (DSM-IV),Citation23 Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE),Citation24 Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA),Citation25 and Addenbrooke’s Cognitive Examination Revised (ACE-R).Citation26–Citation29 The severity of cognitive symptoms could be assessed using the Clinical Dementia Rating (CDR)Citation30 and Geriatric Depression Scale (GDS).Citation31 These neuropsychological assessments have been used to assess different cognitive functions to promote neuropsychological diagnosis and the understanding of cognitive impairment following a stroke diagnosis.

This review will focus on VaD as a common cause of PSD. This work aims to identify the risk factors for cognitive impairment and the effect of such factors on cognitive function. A secondary aim is to assess various neuropsychological assessments used for the early detection of dementia in stroke patients.

Methods

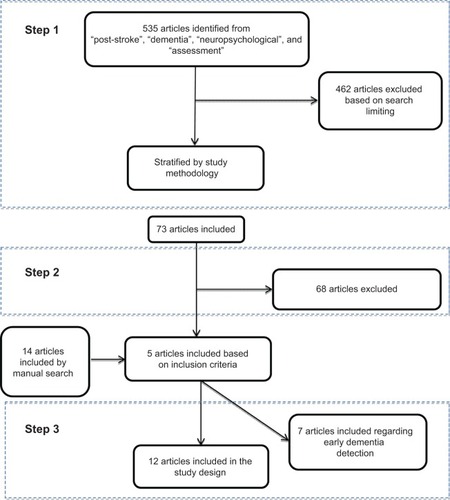

Studies have been performed for PubMed and ScienceDirect. Articles were dated from 2003–2014. The search was based on the following keywords: “post-stroke”; “dementia”; “neuropsychological”; and “assessments”. shows the three steps that were used to select eligible articles. In step 1, the search was limited to English-language and case-control or cohort studies with patients aged 50 years and above and excluded the articles found to be related to brain injury, kidney or pulmonary diseases, heart bypass surgery, aortic valve implementation, and left ventricle assist devices. In addition to the articles related to AD and psychiatric diseases or other dementia types, systematic review, pilot studies, and meta-analysis papers were the primary articles found in this search. Step 2 was based on the following three diagnostic criteria: 1) patient risk factors associated with PSD; 2) description and information about the poststroke cognitive impairment/dysfunction in cognitive function among survivors that had been tested by neuropsychological assessments and evaluated using DSM or other dementia evaluation scales; and 3) PSD evaluation that started from a baseline of first stroke up to 3 months poststroke using neuropsychological assessments. In step 3, due to the limitations imposed by the previous search that focused on the first 3 months after stroke, a manual search of the cited references for related articles identified additional related articles for this research.

Results

Initially, the literature search yielded 535 articles. After applying the search criteria (as in step 1), the number of relevant articles decreased to 73. Step 2 reduced the number of relevant articles to five, and with the manual search, an additional 14 articles were included to yield 19 articles for review.

Association between risk factors and cognitive impairment

shows an overview of the demographic and clinical characteristics of patients on the basis of dementia severity. The relationship between individual risk factors and poststroke VaD development are shown. Several risk factors such as CVD, hypertension, heart disease, and hyperlipidemia, are associated with stroke and VaD development.Citation32 Diabetes mellitus was another risk factor that was highly associated with VaD development. Other factors were cigarette smoking and alcohol intake.

Table 2 Studies investigating the associations between stroke, cognitive impairments, and neuropsychological assessments within 3 months of stroke onset

Demographic determinants, such as age and sex (shown in ), are nonmodifiable risk factors for stroke patients. Compared to the control subjects, the risk of dementia was higher with age and may have resulted in VaD. Age was also correlated with a diagnosis of vascular diseases. However, no significant relationship was observed between dementia development and patient sex.

also shows that CVD was the major risk factor for cognitive impairment and VaD following stroke onset. Modifiable risk factors such as hypertension, heart disease, and diabetes mellitus were the highest risk factors for stroke and dementia, followed by other factors that might predispose subjects to stroke and even VaD.Citation33–Citation38 Moreover, an association between a risk factor and the decline or even loss of one or more cognitive functions (for instance, attention and executive function) were significantly impaired in the studies referenced.Citation33,Citation35–Citation41 This was followed by short-term memory, working memory, and verbal and visual memories, which were significantly impaired in all studies. The decline in cognitive functions was assessed using neuropsychological assessments such as the MMSE, MoCA, ACE-R, and other assessments within the third month of stroke onset.

Focusing on the MMSE score to differentiate dementia severity among patients provided a clear picture of the decreasing trend of the score among stroke patients. Patients were evaluated for VaD using NINDS–AIREN, and the subjects were classified using the DSM-IV or daily living activity assessments.

Function of neuropsychological assessments in the early diagnosis of poststroke VaD

Within the VCI spectrum that ranges from MCI to VaD, efforts have been made to assess patients in the early dementia stage to predict optimal medical treatment for patients. shows that at the early stage (MCI), attention and executive function were affected, which was later followed by the loss of other functions in the memory domain.

shows the poststroke VaD that occurred within the first 3 months of the first stroke onset. All studies used one or more dementia evaluation assessments, such as the DSM-III or DSM-IV, CDR and Mattis Dementia Rating Scale. All studies used the MMSE, in addition to other neuropsychological assessments, to assess patients after stroke diagnosis and dementia evaluation. The evaluation score of MMSE for normal individuals was above 24, but shows that the MMSE score for stroke patients ranged from 17–28. This result indicates that the MMSE cannot accurately measure the cognitive impairment of poststroke patients. MMSE is insensitive to complex cognitive deficits. All patients in the selected articles were evaluated using the MMSE and other neuropsychological assessments to detect cognitive abnormalities after ischemic stroke.

Table 3 Studies presenting the limitations in poststroke memory assessment

Bour et alCitation44 and Cao et alCitation45 reported that MMSE alone is inaccurate for the detection of neuropsychological deficits in young people. The authors recommended an MMSE cutoff of 27 for multiple sclerosis. Yoshida et alCitation46 and Raimondi et alCitation47 used Addenbrooke’s Cognitive Examination (ACE) with the MMSE to detect early dementia, and the authors showed that ACE was more accurate than MMSE. Dong et alCitation48 and Sikaroodi et alCitation49 found that MoCA was superior to MMSE in detecting early dementia. PendleburyCitation50 found that MoCA and ACE-R exhibited good sensitivity and specificity for MCI, and both were feasible as short tests useful for routine clinical practice.

Discussion

Stroke is a CVD that can increase the risk for cognitive impairment and lead to dementia. PSD, particularly VaD, may affect up to 21% of stroke survivors after the third month of stroke onset. This study shows that stroke patient demographics, including age and sex, were associated with cognitive impairment and dementia.

Cognitive impairment increased with age because of the decrease in vessel and cerebral artery inflow. This decrease in cerebral blood flow to the brain may damage the brain and cause cognitive decline. Moreover, the risk factors associated with stroke, including CVD, hypertension, and diabetes mellitus, can be linked to VaD. For example, hypertension can reduce blood flow to the brain, which can lead to VaD and heart diseases, such as atrial fibrillation. This can also reduce cardiac output leading to cerebral hypoperfusion and myocardial infarction and is associated with cognitive decline.

A heavy smoking habit is also a stroke risk factor that can cause decline in memory function. For instance, Atluri et alCitation51 analyzed the molecular mechanisms behind the increase the risk of human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)-associated neurocognitive disorder in HIV-infected heavy cigarette smokers. Impairment in cognitive function, such as attention, executive function, language, short-term memory, working memory, and visual and verbal memories, could also be associated with VCI spectrum stages.

Several neuropsychological assessments are used to test the mental ability of patients following a stroke diagnosis. The MMSE test is widely used for dementia. However, this test only emphasizes language and constructional items. The MMSE cannot predict long-term cognitive decline. Researchers have used the MoCA and ACE-R assessments to detect dementia because both exhibit good sensitivity, particularly at the MCI stage.

This study has some limitations. First, only 19 articles were reviewed because studies on VaD patients, stroke risk factors, and cognitive function within the first 3 months after stroke onset are limited. Moreover, the sample sizes were small and there is a need for additional studies for the early detection and prediction of PSD. Besides, the file drawer problems for all studies in this area of research, many studies may be reviewed but never published, and these studies may have different results from the other studies that have significant findings and are typically published. Despite these drawbacks, this review may provide a means to identify the role of neuropsychological assessments for the early detection of PSD. Finally, cognitive impairments are widely assessed by neuropsychological assessments, but until recently, no specific neuropsychological assessments to evaluate and predict PSD that included memory loss existed.

Future research on the roles of neuropsychological assessments is required to predict and evaluate poststroke VaD, including the evaluation of memory impairment in the early stages. This will reveal subtle changes that might define indicators for the early detection of dementia that will help medical doctors and clinicians in planning and providing a more reliable prediction of the course of the disease. In addition, this will aid in the development of the optimal therapeutic program to provide dementia patients with additional years of a higher quality of life.

Conclusion

This article reviewed the roles of the available neuropsychological assessments in detecting poststroke cognitive impairment and dementia, as well as the affected domain, within the first 3 months of a stroke diagnosis. No specific assessment was suitable for the whole spectrum of the VCI, but several assessment candidates can be suggested for the early detection of the disease. MMSE, MoCA, and ACE-R were among the most useful assessments that would help in the clinical evaluation of cognitive impairment following a stroke. Given their differences in sensitivity and specificity, these tests can be used together to assess different types of patient demographics and risk factors. Combining several assessment methods for neuropsychological testing will be useful and help health care practitioners to provide a suitable treatment program for and to help avoid the cognitive decline of stroke survivors.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- CummingTBMarshallRSLazarRMStroke, cognitive deficits, and rehabilitation: still an incomplete pictureInt J Stroke201381384523280268

- SnaphaanLde LeeuwFEPoststroke memory function in nondemented patients: a systematic review on frequency and neuroimaging correlatesStroke200738119820317158333

- MorrisJCStorandtMMillerJPMild cognitive impairment represents early-stage Alzheimer diseaseArch Neurol200158339740511255443

- TatemichiTKFoulkesMAMohrJPDementia in stroke survivors in the Stroke Data Bank cohort. Prevalence, incidence, risk factors, and computed tomographic findingsStroke19902168588662349588

- LeysDHénonHMackowiak-CordolianiMAPasquierFPoststroke dementiaLancet Neurol200541175275916239182

- FirbankMJBurtonEJBarberRMedial temporal atrophy rather than white matter hyperintensities predict cognitive decline in stroke survivorsNeurobiol Aging200728111664166916934370

- McVeighCPassmorePVascular dementia: prevention and treatmentClin Interv Aging20061322923518046875

- AnkolekarSGeeganageCAndertonPHoggCBathPMClinical trials for preventing post stroke cognitive impairmentJ Neurol Sci20102991–216817420855090

- CummingTBMarshallRSLazarRMStroke, cognitive deficits, and rehabilitation: still an incomplete pictureInt J Stroke201381384523280268

- ErkinjunttiTGauthierSThe concept of vascular cognitive impairmentFront Neurol Neurosci200924798519182465

- IemoloFDuroGRizzoCCastigliaLHachinskiVCarusoCPathophysiology of vascular dementiaImmun Ageing200961319895675

- JacovaCKerteszABlairMFiskJDFeldmanHHNeuropsychological testing and assessment for dementiaAlzheimers Dement20073429931719595951

- DesmondDWVascular dementiaClin Neurosci Res200436437448

- KorczynADVakhapovaVGrinbergLTVascular dementiaJ Neurol Sci20123221–221022575403

- O’BrienJTErkinjunttiTReisbergBVascular cognitive impairmentLancet Neurol200322899812849265

- WinbladBPalmerKKivipeltoMMild cognitive impairment–beyond controversies, towards a consensus: report of the International Working Group on Mild Cognitive ImpairmentJ Intern Med2004256324024615324367

- DauwelsJVialatteFLatchoumaneCJeongJCichockiAEEG synchrony analysis for early diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease: a study with several synchrony measures and EEG data setsConf Proc IEEE Eng Med Biol Soc20092224222719964954

- RuitenbergAOttAvan SwietenJCHofmanABretelerMMIncidence of dementia: does gender make a difference?Neurobiol Aging200122457558011445258

- SnaphaanLRijpkemaMvan UdenIFernándezGde LeeuwFEReduced medial temporal lobe functionality in stroke patients: a functional magnetic resonance imaging studyBrain2009132Pt 71882188819482967

- PlantonMPeifferSAlbucherJFNeuropsychological outcome after a first symptomatic ischaemic stroke with ‘good recovery’Eur J Neurol201219221221921631652

- WerringDJGregoireSMCipolottiLCerebral microbleeds and vascular cognitive impairmentJ Neurol Sci20102991–213113520850134

- ShengBChengLFLawCBLiHLYeungKMLauKKCoexisting cerebral infarction in Alzheimer’s disease is associated with fast dementia progression: applying the National Institute for Neurological Disorders and Stroke/Association Internationale pour la Recherche et l’Enseignement en Neurosciences Neuroimaging Criteria in Alzheimer’s Disease with Concomitant Cerebral InfarctionJ Am Geriatr Soc200755691892217537094

- American Psychiatric AssociationDiagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders4th edWashington, DCAmerican Psychiatric Association1994

- FolsteinMFFolsteinSEMcHughPR“Mini-mental state”: a practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinicianJ Psychiatr Res19751238998

- SmithTGildehNHolmesCThe Montreal Cognitive Assessment: validity and utility in a memory clinic settingCan J Psychiatry200752532933217542384

- MathuranathPSNestorPJBerriosGERakowiczWHodgesJRA brief cognitive test battery to differentiate Alzheimer’s disease and frontotemporal dementiaNeurology200055111613162011113213

- Cedazo-MinguezAWinbladBBiomarkers for Alzheimer’s disease and other forms of dementia: clinical needs, limitations and future aspectsExp Gerontol201045151419796673

- HampelHFrankRBroichKBiomarkers for Alzheimer’s disease: academic, industry and regulatory perspectivesNat Rev Drug Discov20109756057420592748

- BagnoliSFailliYPiaceriISuitability of neuropsychological tests in patients with vascular dementia (VaD)J Neurol Sci20123221–2414522694976

- HughesCPBergLDanzigerWLCobenLAMartinRLA new clinical scale for the staging of dementiaBr J Psychiatry19821405665727104545

- YesavageJABrinkTLRoseTLDevelopment and validation of a geriatric depression screening scale: a preliminary reportJ Psychiatr Res198219831713749

- GorelickPBRisk factors for vascular dementia and Alzheimer diseaseStroke20043511 suppl 12620262215375299

- ThamWAuchusAPThongMProgression of cognitive impairment after stroke: one year results from a longitudinal study of Singaporean stroke patientsJ Neurol Sci20022032044952

- MokVCWongALamWWBaumLWNgHKWongLA case-controlled study of cognitive progression in Chinese lacunar stroke patientsClin Neurol Neurosurg2008110764965618456396

- KhedrEMHamedSAEl-ShereefHKCognitive impairment after cerebrovascular stroke: relationship to vascular risk factorsNeuropsychiatr Dis Treat2009510311619557105

- KandiahNWiryasaputraLNarasimhaluKFrontal subcortical ischemia is crucial for post stroke cognitive impairmentJ Neurol Sci20113091–2929521807379

- JaillardANaegeleBTrabucco-MiguelSLeBasJFHommelMHidden dysfunctioning in subacute strokeStroke20094072473247919461036

- AuchusAPChenCPSodagarSNThongMSngECSingle stroke dementia: insights from 12 cases in SingaporeJ Neurol Sci20022032048589

- StebbinsGTNyenhuisDLWangCGray matter atrophy in patients with ischemic stroke with cognitive impairmentStroke200839378579318258824

- SachdevPSBrodatyHValenzuelaMJLorentzLMKoscheraAProgression of cognitive impairment in stroke patientsNeurology20046391618162315534245

- GrahamNLEmeryTHodgesJRDistinctive cognitive profiles in Alzheimer’s disease and subcortical vascular dementiaJ Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry2004751617114707310

- GarrettKDBrowndykeJNWhelihanWThe neuropsychological profile of vascular cognitive impairment – no dementia: comparisons to patients at risk for cerebrovascular disease and vascular dementiaArch Clin Neuropsychol200419674575715288328

- MokVCWongALamWWCognitive impairment and functional outcome after stroke associated with small vessel diseaseJ Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry200475456056615026497

- BourARasquinSBoreasALimburgMVerheyFHow predictive is the MMSE for cognitive performance after stroke?J Neurol2010257463063720361295

- CaoMFerrariMPatellaRMarraCRasuraMNeuropsychological findings in young-adult stroke patientsArch Clin Neuropsychol200722213314217169527

- YoshidaHTeradaSHondaHValidation of Addenbrooke’s cognitive examination for detecting early dementia in a Japanese populationPsychiatry Res20111851–221121420537725

- RaimondiCGleichgerrchtERichlyPThe Spanish version of the Addenbrooke’s Cognitive Examination – Revised (ACE-R) in subcortical ischemic vascular dementiaJ Neurol Sci20123221–222823122959102

- DongYSharmaVKChanBPThe Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA) is superior to the Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE) for the detection of vascular cognitive impairment after acute strokeJ Neurol Sci20102991–2151820889166

- SikaroodiHYadegariSMiriSRCognitive impairments in patients with cerebrovascular risk factors: a comparison of Mini Mental Status Exam and Montreal Cognitive AssessmentClin Neurol Neurosurg201311581276128023290422

- PendleburySTMarizJBullLMehtaZRothwellPMMoCA, ACE-R, and MMSE versus the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke-Canadian Stroke Network Vascular Cognitive Impairment Harmonization Standards Neuropsychological Battery after TIA and strokeStroke201243246446922156700

- AtluriVSPilakka-KanthikeelSSamikkannuTVorinostat positively regulates synaptic plasticity genes expression and spine density in HIV infected neurons: role of nicotine in progression of HIV-associated neurocognitive disorderMol Brain201473724886748