Abstract

Magnetic seizure therapy (MST) has shown efficacy in adult patients with treatment-resistant depression with limited impairment in memory. To date, the use of MST in adolescent depression has not been reported. Here we describe the first successful use of MST in the treatment of an adolescent patient with refractory bipolar depression. This patient received MST in an ongoing open-label study for treatment-resistant major depression. Treatments employed a twin-coil MST apparatus, with the center of each coil placed over the frontal cortex (ie, each coil centered over F3 and F4). MST was applied at 100 Hz and 100% machine output at progressively increasing train durations. Depressive symptoms were assessed using the 24-item Hamilton Depression Rating Scale and cognitive function was assessed with a comprehensive neuropsychological battery. This adolescent patient achieved full remission of clinical symptoms after an acute course of 18 MST treatments and had no apparent cognitive decline, other than some autobiographical memory impairment that may or may not be related to the MST treatment. This case report suggests that MST may be a safe and well tolerated intervention for adolescents with treatment-resistant bipolar depression. Pilot studies to further evaluate the effectiveness and safety of MST in adolescents warrant consideration.

Introduction

Major depression is a common disorder in adolescence and an important public health concern. The incidence of depression in adolescence ranges from 2.5% to 8%.Citation1 Major depression in adolescence is also associated with an increased risk of suicide, poor school performance, impaired social skills, social withdrawal, and substance abuse.Citation2 Depressive symptoms in adolescents can be different from those in adults. In adolescent depression, symptoms are more heterogeneous and can fluctuate. Symptoms of major depression can also manifest as somatic complaints and are highly comorbid with anxiety disorders, substance abuse, disruptive behavior disorders (eg, conduct disorder and oppositional defiant disorder), personality disorders, and attention deficit disorder.Citation3–Citation6 Effective treatments for mild to moderate depression in adolescents may include selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors, cognitive-behavioral therapy, and interpersonal therapy.Citation7 However, these treatments may be of limited efficacy in patients with severe symptoms. Moreover, psychotropic medications can frequently produce intolerable side effects.Citation8 Furthermore, bipolar depression is poorly understood in youth and there is a dearth of evidence-based treatments. In general, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors are used with caution because there are limited data to suggest these agents are effective and concern that they may induce manic episodes.Citation9,Citation10 Also, recent meta-analyses showed that adolescent patients initiating therapy with a high dose of antidepressants seem to be at heightened risk of deliberate self-harm and that the efficacy of antidepressant therapy for youth seems to be modest.Citation11,Citation12 Further, separate evidence suggests that the antidepressant dose is generally unrelated to the therapeutic efficacy.Citation13–Citation18

Electroconvulsive therapy (ECT) may be of significant benefit in adolescents who present with treatment-resistant depression.Citation8 However, ECT is often associated with significant memory impairment and its use in adolescents with depression is still controversial.Citation19 Repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation (rTMS) has also been used to treat adolescent depression with very good tolerability and few adverse effects.Citation20–Citation22 Early evidence also suggests that treatment of resistant depression by rTMS in adolescents is not associated with long-term cognitive deterioration and that some patients may derive long-term benefit from rTMS.Citation23 However, although rTMS is relatively well tolerated in adolescent patients with major depression, there are also reports suggesting that rTMS may not be perceived as being very helpful by patients and their parents,Citation24 and its efficacy in adolescents has only been evaluated in a small number of open-label studies.

Magnetic seizure therapy (MST) has shown efficacy in adult patients with treatment-resistant depression without significant impairment in memory.Citation25–Citation27 A small randomized clinical trial of MST and ECT demonstrated equivalent antidepressant efficacy with minimal cognitive side effects in adult treatment-resistant depression.Citation28 To date, the use of MST in adolescent depression has not been reported. Herein, we describe the first use of MST in an adolescent patient with a treatment-resistant major depressive episode in the context of bipolar II disorder who experienced full remission of depressive symptoms with no deleterious effects on memory.

Materials and methods

The current report describes the case of a patient with adolescent bipolar depression who achieved remission in an ongoing open-label study of MST (NCT01596608). The patient’s diagnosis of a major depressive episode in the context of bipolar II disorder was confirmed using the SCID-IV (Structured Clinical Interviews for the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition).

In the acute treatment phase, MST was administered at a frequency of 2–3 times per week on nonconsecutive days. In the continuation treatment phase, MST was administered at a frequency of once per week for 4 weeks, one treatment every 2 weeks for 2 months, and one treatment every 3 weeks for one month, in succession. This patient had a total of 18 MST treatment sessions in the acute treatment phase and nine treatment sessions in the continuation phase. A twin coil was used for MST (Mag Venture A/S, Farum, Denmark), and the center of each coil was placed over F3 and F4 using the 10–20 electroencephalography system. The MST determination of seizure threshold used 100% machine output applied at 100 Hz at progressively increasing train durations, commencing at 2 seconds and increasing by 2 seconds with each subsequent stimulation until an adequate seizure was produced. During subsequent sessions, one stimulation per session was delivered using a train duration that was 4 seconds longer than the train duration at threshold (with a maximum train duration of 10 seconds). Methohexital sodium 0.75 mg/kg and succinylcholine 0.5 mg/kg were administered for induction of anesthesia and muscle relaxation.

The primary outcome measure was remission on the 24-item version of the Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (HDRS). Remission was defined as an HDRS 24-item score ≤10 and a 60% reduction in scores on two consecutive assessments, consistent with other larger convulsive therapy trials.Citation29,Citation30 Clinical/cognitive assessments were performed by trained research analysts.

Cognition was assessed prior to and at the end of the acute treatment phase, and at 6 months post treatment. Additionally, the Montreal Cognitive Assessment was administered at baseline and every six treatments during acute treatment, and also before the first continuation treatment. It was then administered once a month during continuation treatment. The full cognitive battery included assessments of anterograde and retrograde memory, specifically looking at learning, retention, and retrieval in both the verbal and nonverbal domains. This included assessments such as the Autobiographical Memory Interview Short Form (AMI-SF),Citation31 MATRICS Consensus Cognitive Battery, Stroop, and verbal fluency using the Controlled Oral Word Association Test (COWAT). We also evaluated general intellectual functioning through the Wechsler Test of Adult Reading prior to the start of treatment. Finally, time to reorientation was measured to assess the recovery of orientation post-MST treatment.

Results

The patient was an 18-year-old male with a first refractory major depressive episode in the context of bipolar II disorder. The depressive episode was of moderate severity without psychotic symptoms. Prior to the onset of the depressive episode, he had intentionally deprived himself of sleep to study harder. He felt he had the ability to study harder, stay up longer, and work harder than his classmates. After approximately 3 weeks of intentionally staying up late and sleeping only 4 hours, he developed significant depressive symptoms that continued for more than 2 months. At the onset of this depressive episode, he was evaluated and treated by a psychiatrist, and had trials of citalopram, sertraline, methylphenidate, risperidone, aripiprazole, quetiapine, and lithium during the depressive episode for 12 months. However, these antidepressants and mood stabilizers had little effect on his depressive symptoms. The patient was subsequently referred for a course of rTMS. He received bilateral dorsal medial prefrontal cortex rTMS treatment at 10 Hz, 1,500 pulses per sessionCitation32 delivered as an accelerated treatment of five sessions daily at 2-hour intervals for 5 days.Citation32–Citation34 Before rTMS, his 17-item HDRS score was 16, which improved to 9 after rTMS. He had a partial response of less than 50% that was not felt to be clinically significant. His improvement was short-lived after completing rTMS, and he was referred to the Temerty Centre for Therapeutic Brain Intervention at the Centre for Addiction and Mental Health and met the eligibility criteria for the ongoing, open-label clinical trial of MST (NCT01596608).

At the time of initial assessment, his depressive episode had reached 58 weeks in duration and he was experiencing anhedonia. His energy was low and he reported poor concentration and low self-esteem. His appetite was very poor but he had not lost weight. He denied having feelings of guilt or worthlessness. However, he felt very indecisive and could not decide what to do. He had thoughts of not wanting to live but had no suicidal ideation. He denied any paranoid, persecutory, guilty, or somatic delusions. He drank alcohol only occasionally. Other than the hypomania preceding the current depressive episode, there did not appear to be any other episodes of mania or hypomania. There had been no hospitalizations or suicide attempts. He had mild hypothyroidism that was treated with thyroxine. He was euthyroid (thyroid-stimulating hormone level 3.56 mIU/L) after thyroxine replacement therapy. There was no history of seizure, loss of consciousness, or any surgery. He did not have any metal implants in his brain.

Before starting MST treatments, both methylphenidate and lithium were tapered in consideration of the increased risk of cardiac sequelae and cognitive impairment associated with these drugs. Concomitant lithium therapy is prohibited during the MST clinical trial due to the potential for increased adverse cognitive effects when lithium is combined with ECT.Citation35 He had an acute course of 18 MST treatments over 6 weeks and nine continuation MST treatments over 6 months. During his course of MST treatments, he was on no medications other than thyroxine 0.05 mg per day orally.

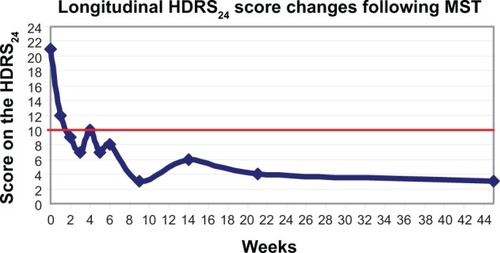

At baseline, prior to starting MST treatments, his score on the 24-item HDRS was 21. His mean time to reorientation post-MST treatment was 29±21 minutes. After the 12th MST treatment, his HDRS 24-item score was reduced to 10, and he stated that he had increased interest and wanted to return to school. In addition, he no longer demonstrated psychomotor retardation. He achieved remission after his 18th MST treatment when his HDRS 24-item score was 8. Although his processing speed and concentration improved, we continued his MST treatment according to the protocol described above as continuation MST for prevention of relapse. After his 21st MST treatment, his HDRS 24-item score ranged from three to six. His mood and energy remained good, and he continued to be physically active. shows the longitudinal changes in clinical outcomes measured with the 24-item HDRS.

Figure 1 Longitudinal changes in clinical outcome measured with the HDRS24. The red line indicates the remission score cut-off point of 10 on the HDRS24.

The main results of the comprehensive neuropsychological battery at baseline and after acute and continuation treatment are reported in . Also, his average score on the Montreal Cognitive Assessment was 29±1 points out of 30 (cut-off point is 26), suggesting that his general cognitive function was within normal limits during the entire course of MST.

Table 1 Neuropsychological battery at baseline, after acute treatment, and after continuation treatment

The adverse effects of MST in the patient were intense nausea after the first MST treatment and multiple prolonged seizures that required termination with midazolam or extra methohexital. After MST treatment, granisetron 1 mg or odansetron 4 mg was used to alleviate nausea at each subsequent treatment. For prolonged seizures over 150 seconds, in his acute course of MST, mean electroencephalographic and electromyographic seizures were 132±62 seconds (on frontal EEG) and 94±42 seconds (physical manifestation). At the acute MST 1, 3, 8, and 17 sessions, his prolonged seizures were terminated with midazolam 1–2 mg. During the continuation course of MST, mean electroencephalographic and physical seizures were 170±33 seconds and 146±28 seconds, respectively. During the continuation MST 2 and 6 treatments, his prolonged seizures were terminated with midazolam 2 mg and at treatments 3, 4, 7, 8, and 9 they were terminated with methohexital 30–40 mg. The details of his are shown in .

Table 2 Mean values during the acute and continuation treatment courses

Despite experiencing multiple prolonged seizures, he was able to return to and attend university for full-time studies following completion of the MST treatments.

Discussion

This is the first case report of an adolescent who was experiencing a treatment-resistant major depressive episode in the context of bipolar II who achieved remission of his previously refractory depression following a course of MST. His symptoms were unresponsive to several antidepressants, mood stabilizers, and augmentation therapies, and had been present for more than one year. Due to multiple psychopharmacological treatment failures, treatment with rTMS, ECT, and MST were considered as treatment options.Citation27,Citation36,Citation37 After the patient had a transient partial response to rTMS, he and his family decided to participate in our MST treatment trial.

The patient reached remission after 18 acute (ie, 2–3 times per week) MST treatments. He has maintained his remission for approximately 11 months at the time of this report. He experienced no prolonged confusion after MST treatments, consistent with a previous report.Citation38 Finally, there was minimal subjective cognitive impairment during his MST course. He did have a reduced autobiographical memory score on testing, but this did not lead to any functional impairment.

Previous studies have reported that healthy subjects demonstrate decreased retrieval consistency in all components of the AMI-SF. For example, mean retrieval consistency in all components of the AMI-SF was approximately 80% between the initial assessment and 6 months post reassessment.Citation39 Also, Semkovska et al proposed cut-off values defining impairment for both initial assessment and consistency in autobiographical memory retrieval after 6 months. These values were 33.5 and 23.5, respectively.Citation39 His scores of 52 on the AMI-SF at the initial assessment and 35 at the 6 months post reassessment were within the normal range. Further, while patients with depression showed less episodic-specific autobiographical memory than healthy controls in the study by Semkovska et al both groups showed equivalent amounts of consistency loss over a 2-month interval on all components of the AMI-SF.Citation39 Based on these findings in healthy subjects, an approximately 20% reduction in AMI-SF score can be expected between the initial assessment and 6 months post reassessment. Therefore, in this patient, we would anticipate an AMI-SF score of 42 points at 6 months post assessment compared with his actual score of 35 points. The gap between his expected 42 point (ie, 20% reduction) and his actual 35 point (ie, 33% reduction) may be related to normal variability in performance or possibly to a mild retrograde amnesia related to MST. In the case of ECT, the evidence suggests that impairment of autobiographical memory does occur after an acute course, with effect sizes (Cohen’s d) ranging from −2.69 to −0.01.Citation40,Citation41 For example, while post-ECT deficits as cognitive adverse effects were observed with the Mini-Mental State Examination, accuracy on the N-Back test, the Buschke Selective Reminding Test, and AMI-SF measures, the magnitude was substantially greater for the AMI-SF.Citation29 Also, other studies demonstrated that loss of autobiographical memory is still present between one and 6 months after unilateral brief pulse ECTCitation29,Citation42–Citation46 with large effect sizes,Citation43,Citation44 while ultrabrief pulse right unilateral ECT shows less decline in autobiographical memory, with nil to small effect sizes.Citation29,Citation46,Citation47

In summary, our case report suggests that MST may be promising for treatment-resistant depression in adolescents. Larger studies are needed to confirm the effectiveness and safety of MST in this population.

Disclosure

In the last 5 years, DMB has received research support from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research, Brain and Behaviour Research Foundation (formerly NARSAD), the Temerty family through the Centre for Addiction and Mental Health Foundation and the Campbell Research Institute, and for an investigator-initiated study from Brainsway Ltd. ZJD received research and equipment in kind support for an investigator-initiated study through Brainsway Inc., and a travel allowance through Merck. ZJD has also received speaker funding through Sepracor Inc., and AstraZeneca, served on advisory boards for Hoffmann-La Roche Limited and Merck, and received speaker support from Eli Lilly. This work was supported by the Ontario Mental Health Foundation, the Canadian Institutes of Health Research, the Brain and Behaviour Research Foundation, and the Temerty family and Grant family through the Centre for Addiction and Mental Health Foundation and the Campbell Institute. PBF is supported by the National Health and Medical Research Council Practitioner Fellowship, and has received equipment for research from Magventure A/S, Brainsway, Medtronic, and Cervel Neurotech, and research funding from Cervel Neurotech. PEC is supported by the National Institute of Mental Health of the National Institutes of Health (K23MH100266). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health. PEC also receives research support from Brain and Behaviour Research Foundation Young Investigator Grant. JD receives research support from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research, the Ontario Brain Institute, the Buchan Family Foundation, and the Klarman Family Foundation, and has received in-kind equipment loans from MagVenture for research on investigator-initiated studies. YN reports no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- RichardsonLPKatzenellenbogenRChildhood and adolescent depression: the role of primary care providers in diagnosis and treatmentCurr Probl Pediatr Adolesc Health Care200535162415611721

- WellerEBKloosAKangJWellerRADepression in children and adolescents: does gender make a difference?Curr Psychiatry Rep20068210811416539885

- RenoufAGKovacsMMukerjiPRelationship of depressive, conduct, and comorbid disorders and social functioning in childhoodJ Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry199736799810049204679

- AngoldACostelloEJErkanliAComorbidityJ Child Psychol Psychiatry1999401578710102726

- SmallDMSimonsADYovanoffPDepressed adolescents and comorbid psychiatric disorders: are there differences in the presentation of depression?J Abnorm Child Psychol20083671015102818509755

- ParisJRecent research in personality disorders. PrefacePsychiatr Clin North Am2008313xixii18638639

- MilinRWalkerSChowJMajor depressive disorder in adolescence: a brief review of the recent treatment literatureCan J Psychiatry200348960060614631880

- ReyJMWalterGHalf a century of ECT use in young peopleAm J Psychiatry199715455956029137112

- GoldsteinBISassiRDilerRSPharmacologic treatment of bipolar disorder in children and adolescentsChild Adolesc Psychiatr Clin N Am201221491193923040907

- DeFilippisMSWagnerKDBipolar depression in children and adolescentsCNS Spectr201318420921323570693

- JureidiniJNDoeckeCJMansfieldPRHabyMMMenkesDBTonkinALEfficacy and safety of antidepressants for children and adolescentsBMJ2004328744487988315073072

- TsapakisEMSoldaniFTondoLBaldessariniRJEfficacy of antidepressants in juvenile depression: meta-analysisBr J Psychiatry20081931101718700212

- BolliniPPampallonaSTibaldiGKupelnickBMunizzaCEffectiveness of antidepressants. Meta-analysis of dose-effect relationships in randomised clinical trialsBr J Psychiatry199917429730310533547

- BechPTanghojPAndersenHFOveroKCitalopram dose-response revisited using an alternative psychometric approach to evaluate clinical effects of four fixed citalopram doses compared to placebo in patients with major depressionPsychopharmacology20021631202512185396

- AdliMBaethgeCHeinzALanglitzNBauerMIs dose escalation of antidepressants a rational strategy after a medium-dose treatment has failed? A systematic reviewEur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci2005255638740015868067

- RuheHGHuyserJSwinkelsJAScheneAHDose escalation for insufficient response to standard-dose selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors in major depressive disorder: systematic reviewBr J Psychiatry200618930931617012653

- RuheHGBooijJv WeertHCEvidence why paroxetine dose escalation is not effective in major depressive disorder: a randomized controlled trial with assessment of serotonin transporter occupancyNeuropsychopharmacology2009344999101018830236

- HansenRAMooreCGDusetzinaSBLeinwandBIGartlehnerGGaynesBNControlling for drug dose in systematic review and meta-analysis: a case study of the effect of antidepressant doseMed Decis Making20092919110319141788

- QuintanaHTranscranial magnetic stimulation in persons younger than the age of 18J ECT2005212889515905749

- D’AgatiDBlochYLevkovitzYRetiIrTMS for adolescents: safety and efficacy considerationsPsychiatry Res2010177328028520381158

- CroarkinPEWallCALeeJApplications of transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS) in child and adolescent psychiatryInt Rev Psychiatry201123544545322200134

- HuangMLLuoBYHuJBRepetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation in combination with citalopram in young patients with first-episode major depressive disorder: a double-blind, randomized, sham-controlled trialAust N Z J Psychiatry201246325726422391283

- MayerGAviramSWalterGLevkovitzYBlochYLong-term follow-up of adolescents with resistant depression treated with repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulationJ ECT2012282848622531199

- MayerGFaivelNAviramSWalterGBlochYRepetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation in depressed adolescents: experience, knowledge, and attitudes of recipients and their parentsJ ECT201228210410722513510

- LisanbySHLuberBSchlaepferTESackeimHASafety and feasibility of magnetic seizure therapy (MST) in major depression: randomized within-subject comparison with electroconvulsive therapyNeuropsychopharmacology200328101852186512865903

- McClintockSMTirmiziOChansardMHusainMMA systematic review of the neurocognitive effects of magnetic seizure therapyInt Rev Psychiatry201123541342322200131

- WaniATrevinoKMarnellPHusainMMAdvances in brain stimulation for depressionAnn Clin Psychiatry201325321722423926577

- KayserSBewernickBHGrubertCHadrysiewiczBLAxmacherNSchlaepferTEAntidepressant effects, of magnetic seizure therapy and electroconvulsive therapy, in treatment-resistant depressionJ Psychiatr Res201145556957620951997

- SackeimHADillinghamEMPrudicJEffect of concomitant pharmacotherapy on electroconvulsive therapy outcomes: short-term efficacy and adverse effectsArch Gen Psychiatry200966772973719581564

- KellnerCHKnappRHusainMMBifrontal, bitemporal and right unilateral electrode placement in ECT: randomised trialBr J Psychiatry2010196322623420194546

- KingMJMacDougallAGFerrisSMLevineBMacQueenGMMcKinnonMCA review of factors that moderate autobiographical memory performance in patients with major depressive disorderJ Clin Exp Neuropsychol201032101122114420544462

- DownarJGeraciJSalomonsTVAnhedonia and reward-circuit connectivity distinguish nonresponders from responders to dorsomedial prefrontal repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation in major depressionBiol Psychiatry201476317618524388670

- HoltzheimerPE3rdMcDonaldWMMuftiMAccelerated repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation for treatment-resistant depressionDepress Anxiety2010271096096320734360

- BaekenCMarinazzoDWuGRAccelerated HF-rTMS in treatment-resistant unipolar depression: Insights from subgenual anterior cingulate functional connectivityWorld J Biol Psychiatry201415428629724447053

- EmilienGMaloteauxJMLithium neurotoxicity at low therapeutic doses. Hypotheses for causes and mechanism of action following a retrospective analysis of published case reportsActa Neurol Belg19969642812939008777

- CusinCDoughertyDDSomatic therapies for treatment-resistant depression: ECT, TMS, VNS, DBSBiol Mood Anxiety Disord2012211422901565

- BlumbergerDMMulsantBHDaskalakisZJWhat is the role of brain stimulation therapies in the treatment of depression?Curr Psychiatry Rep201315736823712719

- KirovGEbmeierKPScottAIQuick recovery of orientation after magnetic seizure therapy for major depressive disorderBr J Psychiatry2008193215215518670002

- SemkovskaMNooneMCartonMMcLoughlinDMMeasuring consistency of autobiographical memory recall in depressionPsychiatry Res20121971/2414822397910

- FraserLMO’CarrollREEbmeierKPThe effect of electroconvulsive therapy on autobiographical memory: a systematic reviewJ ECT2008241101718379329

- VerwijkEComijsHCKokRMSpaansHPStekMLScherderEJNeurocognitive effects after brief pulse and ultrabrief pulse unilateral electroconvulsive therapy for major depression: a reviewJ Affect Disord2012140323324322595374

- McElhineyMCMoodyBJSteifBLAutobiographical memory and mood: effects of electroconvulsive therapyNeuropsychology19959501517

- NgCSchweitzerIAlexopoulosPEfficacy and cognitive effects of right unilateral electroconvulsive therapyJ ECT200016437037911314875

- McCallWVDunnARosenquistPBHughesDMarkedly suprathreshold right unilateral ECT versus minimally suprathreshold bilateral ECT: antidepressant and memory effectsJ ECT200218312612912394530

- O’ConnorMBrenninkmeyerCMorganARelative effects of repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation and electroconvulsive therapy on mood and memory: a neurocognitive risk-benefit analysisCogn Behav Neurol200316211812712799598

- LooCKSainsburyKSheehanPLyndonBA comparison of RUL ultrabrief pulse (0.3 ms) ECT and standard RUL ECTInt J Neuropsychopharmacol200811788389018752719

- SienaertPVansteelandtKDemyttenaereKPeuskensJRandomized comparison of ultra-brief bifrontal and unilateral electroconvulsive therapy for major depression: cognitive side-effectsJ Affect Disord20101221/2606719577808