Abstract

Introduction

Adherence to glaucoma treatment is poor, potentially reducing therapeutic effects. A glaucoma educator was trained to use motivational interviewing (MI), a patient-centered counseling style, to improve adherence. This study was designed to evaluate whether MI was feasible in a busy ophthalmology practice.

Methods

Feasibility was assessed using five criteria from the National Institutes of Health Behavior Change consortium: fidelity of intervention components to MI theory; success of the training process; delivery of MI-consistent interventions by the glaucoma educator; patient receipt of the intervention based on enrollment, attrition, and satisfaction; and patient enactment of changes in motivation and adherence over the course of the intervention.

Results

A treatment manual was designed by a multidisciplinary team with expertise in health psychology, public health, and ophthalmology. The glaucoma educator received 6 hours of training including role-play exercises, self-study, and individual supervision. His MI-related knowledge and skills increased following training, and he delivered exclusively MI-consistent interventions in 66% of patient encounters. 86% (12/14) of eligible patients agreed to be randomized into glaucoma educator support or a control condition. All 8 patients assigned to the glaucoma educator completed at least 2 of 6 planned contacts, and 50% (4/8) completed all 6 contacts. Patients assigned to the glaucoma educator improved over time in both motivation and adherence.

Conclusion

The introduction of a glaucoma educator was feasible in a busy ophthalmology practice. Patients improved their adherence while participating in the glaucoma educator program, although this study was not designed to show a causal effect. The use of a glaucoma educator to improve glaucoma patients’ medication adherence may be feasible at other ophthalmology clinics, and can be implemented with a standardized training approach. Pilot data show the intervention can be implemented with fidelity, is acceptable to patients and providers, and has the potential to improve adherence.

Introduction

Glaucoma is a leading cause of blindness worldwide.Citation1,Citation2 In the United States alone, over 2 million people have glaucoma, and 130,000 are legally blind from this disease.Citation3,Citation4 Unfortunately, medication nonadherence is an ongoing barrier to treatment. In one early study, glaucoma patients were just 42% adherent after being told they could go blind, and adherence improved only to 58% among patients who had already gone blind in one eye.Citation5 Although medications have improved since that time with fewer doses per day and decreased systemic side effects, nonadherence to current glaucoma medications is still close to 50%.Citation6

Barriers to glaucoma treatment adherence include medication regimen characteristics, logistical issues like scheduling challenges, individual patient factors like memory problems, and poor doctor–patient communication. In a recent survey, 50% of ophthalmologists said that patients’ lack of motivation for treatment was a barrier to adherence, 55% said that medication cost reduced patients’ adherence, and 41% said that patients’ lack of knowledge about treatment was a primary barrier to adherence.Citation7 However, studies of patients’ actual adherence behavior have found only a modest association between treatment-related knowledge and adherence.Citation8 Patients’ negative attitudes toward treatment appear to be a more important determinant of nonadherence than lack of knowledge: patients who do not believe that nonadherence might lead to reduced vision are less likely to adhere to treatment, as are patients who report concerns about cost or trouble staying adherent while traveling.Citation9 About one-third of glaucoma nonadherence is intentional, with patients being less likely to take medication if they see no need for it or are not concerned about the potential consequences of nonadherence. Citation10 Demographic and clinical variables including gender, marital status, geographic area, and treatment duration do not predict adherence.Citation8 However, age, minority race/ethnicity, and comorbid medical illness have been found to predict nonadherence in some studies.Citation11

Motivational interviewing to improve medication adherence

Support and education from medical professionals can increase adherence.Citation12 One model of provider-delivered support is motivational interviewing (MI), a counseling style focused on exploration and resolution of patients’ ambivalence. Citation13 Several meta-analytic reviewsCitation14,Citation15 demonstrate MI’s utility for health behavior problems including nonadherence: It has been successfully used by primary care practitioners to promote healthy behaviors,Citation16 by diabetes specialists to increase physical activity,Citation17 and by dentists to improve oral health behaviors.Citation18 In addition, nurse-delivered telephonic counseling using MI has been found to improve medication adherence for endometriosis,Citation19 osteoporosis,Citation20 serious and persistent mental illness,Citation21 HIV,Citation22 and ulcerative colitis.Citation23 MI may be particularly helpful to patients from minority cultural groups.Citation24

To our knowledge, MI has not been used in ophthalmology practice, a setting that presents several challenges. First, glaucoma care traditionally has been conducted directly between physicians and patients, with little involvement of ancillary staff like nurses or care managers. However, patients and their ophthalmology providers may have different perceptions of adherence.Citation18 Second, counseling techniques like MI are less familiar to ophthalmology practitioners than to those in other specialties, and require a communication style that is substantially different from ophthalmologists’ customary physician-directed approach.Citation25 Third, patients may not be accustomed to receiving education or counseling from their ophthalmology providers. Finally, as in most care settings, lack of time and funding are barriers to change.Citation26

Can MI be delivered by a glaucoma educator in ophthalmology practice?

This pilot study was designed to evaluate the feasibility of training a glaucoma educator to implement MI with patients at an outpatient ophthalmology practice. The rationale for adding a glaucoma educator was three-fold: (a) patients may benefit from extra time with a health care professional; (b) patients may feel more comfortable asking questions of an ancillary provider;Citation27 and (c) educators can interact with patients using a style different from the traditional medical model.Citation13 If MI delivered by a glaucoma educator improves adherence, this may also lead to reduced intraocular pressure, preservation of visual field, improved quality of life, delayed need for specialized or long-term care, and reduced overall health care costs. But because glaucoma educators and MI counseling are not currently part of ophthalmology practices, the feasibility of this approach must first be established.

Feasibility was evaluated using criteria from the NIH Behavior Change Consortium.Citation28,Citation29 This 5-level conceptualization suggests that an intervention is translated to a new setting with high fidelity if it has adequate adherence to theory, if it is implemented successfully, delivered consistently by interventionists, and successfully received by patients, and if patients enact recommended changes in behavior.

Methods

Participants

Participants were recruited from the tertiary glaucoma clinic of one of the authors (MYK) at the Rocky Mountain Lions Eye Institute, Denver, CO in 2008. Physicians identified adult patients with primary or secondary open-angle glaucoma who were prescribed monotherapy topical glaucoma medication. Exclusion criteria were: patient-reported inability to administer eye drops, cognitive impairment, physician’s determination that glaucoma surgery was likely within 6 months, or >80% adherence during a 2-month run-in phase. Eligible patients were randomized to receive either standard glaucoma care or standard care plus glaucoma educator counseling. Patients did not receive any incentives for participating in the study.

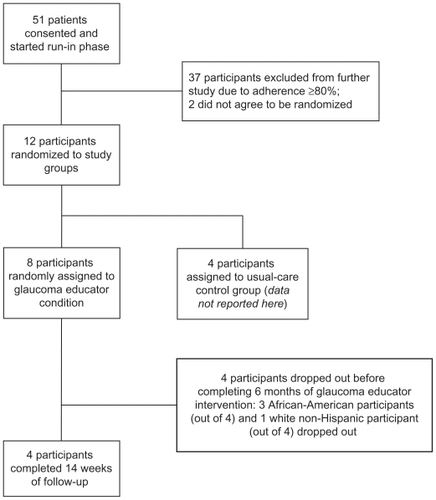

Fifty-one patients consented, and 14 were <80% adherent. The high rate of adherence in 73% (37/51) of screened patients may have resulted from adherence monitoring during the run-in phase. Twelve of these patients consented to be randomized, and 8 were assigned to the glaucoma educator intervention. Patient recruitment and study flow are shown in .

Procedure

This study was approved by the Colorado Multiple Institutional Review Board, and participants gave written informed consent. On average, 35–40 patients were seen per half day of clinic during the recruitment period. Patients were approached to participate by their ophthalmologist and those who agreed were escorted by the clinic study coordinator to a research examination lane where the consent process was completed. During the run-in phase and intervention, participants stored their medication eye-dropper in a bottle with a Medication Event Monitoring System (MEMS) cap. MEMS caps are electronic devices that record the time and date a pill bottle is opened. Bottles with MEMS caps accommodate all currently used glaucoma eye drops. Patients were given the MEMS bottle by the clinic study coordinator at the time they provided informed consent, and they returned to the clinic for a second meeting with the study coordinator at the end of the 2-month run-in period to determine baseline adherence and study eligibility. Eligible patients randomized to the glaucoma educator condition were then scheduled for their initial educator visit at a later date. The glaucoma educator had no previous contact with any of the study participants. MEMS data were also downloaded and analyzed at each in-person glaucoma educator visit. Participants were aware that MEMS were being used to monitor their medication use. The long run-in period was designed to ensure that any improvements in adherence due to MEMS use occurred prior to the glaucoma educator intervention so that any further improvements in adherence would be attributable to the MI intervention.

Participants assigned to the glaucoma educator were scheduled to receive three one-to-one meetings with the glaucoma educator and three phone calls. Each included a review of the participant’s current adherence, barriers to taking medication, side effects, and questions about treatment. The glaucoma educator was trained to recognize and address habits, beliefs, and emotions that interfere with adherence, and to respond within an MI counseling framework.Citation19 To reinforce teaching points, the educator distributed print material approved by the American Academy of Ophthalmology.

The first glaucoma educator session was scheduled within 1 week after randomization. Follow-up calls were scheduled 1, 6, and 14 weeks later, with in-person meetings scheduled 4 and 12 weeks post-randomization. Patients continued to receive care from their ophthalmologists, who were masked to patients’ group assignment.

Measures

Theory fidelity

MI is based on four principles, summarized in : express empathy, roll with resistance, develop discrepancy, and support self-efficacy.Citation30 These principles define an empathic counseling style focused on listening carefully to individual patients’ concerns, increasing patients’ awareness about unintended consequences of behavior, avoiding argument or lecturing, and encouraging patients to develop their own solutions and make informed decisions about adherence. The empathic and directive “spirit” of MI is more important than specific counselor behaviors.Citation31 A manual and counselor tools were developed for this intervention, and their fidelity to MI theory was evaluated by multidisciplinary expert review. The educator’s feedback was also obtained.

Table 1 Motivational interviewing (MI) counseling style

Glaucoma educator training

The training process was documented, including the glaucoma educator’s prior counseling experience, training received, and follow-up consultation. The educator’s knowledge and comfort with the intervention were assessed using standardized educational evaluation tools.Citation32

Implementation of MI

Implementation was documented using a session record form developed for this study. Session length and number of contacts were recorded. The glaucoma educator also reported his use of MI techniques, participants’ current adherence, any barriers identified, and participants’ readiness for change.

Patient receipt of MI

Receipt is the degree to which patients receive the intervention as designed. Receipt was evaluated based on eligible patients’ participation and attrition from the program over time.

Patient enactment

Enactment is the degree to which participants take necessary follow-up steps, such as increasing motivation or changing behavior. Motivation was assessed at each session via a stage-of-change ratingCitation33 by the glaucoma educator, coded numerically on a 1–4 scale with 1 indicating the lowest readiness for change and 4 the highest. Adherence was based on MEMS data, which are widely regarded as valid,Citation34 do not have a strong direct effect on patients’ medication-taking behavior,Citation35 and have been used in glaucoma research.Citation7,Citation28,Citation29 Although MEMS data are considered as close to a “gold standard” as exists in the science of medication adherence, using multiple measures is always preferredCitation36 because MEMS record only the first step in using medication (opening the bottle) rather than an actual attempt to administer the medication or verification that eye drops were administered correctly. Therefore, MEMS data were supplemented with a clinical interview measure that has shown >70% agreement with pharmacy data.Citation20 For both measures, adherence was defined as the percentage of days since the last session on which medication was taken as prescribed, based on the number of doses taken but not on the specific timing of doses. This adherence metric was selected to keep the two measures comparable, and to minimize recall bias in patient reports.

Data analysis

Analyses were primarily descriptive statistics, calculated using SPSS software (v. 17; SPSS, Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). For patient enactment measures, the multilevel modeling program HLM 6.03 (Scientific Software International Inc., Lincolnwood, IL) was used to evaluate within-patient changes in motivation and behavior over time.

Results

Results for the five dimensions of treatment fidelity are summarized in .

Table 2 Treatment fidelity of motivational interviewing (MI) in outpatient glaucoma care

Theory fidelity

The authors created an intervention manual with information about why traditional patient education is ineffective, basic MI strategies (eg, open-ended questions, acceptance, reflection, and summarizing), the “ask-tell-ask” method of patient education, additional techniques for patients who appear “resistant” to change, and problem-solving strategies for more motivated patients. A form was also developed to document counseling sessions.

The manual and session record form were reviewed by experts in health psychology, public health, and ophthalmology. Additional feedback was obtained from three colleagues with expertise in MI, each of whom has a terminal degree in nursing or social work and at least 5 years of clinical experience in health behavior change. All components were viewed as being consistent with the theory of behavior change underlying MI.Citation24 Suggestions incorporated from this review focused on addressing logistical barriers to adherence and changes in the exact wording of interventions. Additional feedback was requested from the glaucoma educator, who requested further information about cultural competence and mental health issues that might interfere with adherence. These topics were incorporated into an additional training session and practice exercises.

Glaucoma educator training

The glaucoma educator was a certified ophthalmic technician with over 12 years of clinical experience. He completed training with two ophthalmologists on glaucoma drops and their side effects. He then reviewed the intervention manual and completed in-person training with one of the authors (PFC), a psychologist with expertise in health behavior change. Training included discussion of the manual, role-playing patient scenarios, and individual consultation to discuss the first few patients seen. Training that includes face-to-face instruction plus supervised practice over time is more efficacious than single-day workshops or self-study alone.Citation37

At the start of training, the educator had excellent interpersonal skills and some patient education experience, but no experience using MI. By the end of training, he almost exclusively used MI-consistent techniques during role-play and always elicited the patient’s knowledge and reactions before offering educational messages. The trainer’s ratings of the educator’s MI skills reflected this improvement. In addition, the educator’s self-assessed knowledge of MI, willingness to use MI, and reported use of eight MI-consistent techniques each increased from pre- to post-training.

Implementation of MI

Based on the session record form, the counselor used MI-consistent listening techniques 100% of the time. For patients with low readiness for change, all 13 counseling sessions involved elicitation, reflection, and summarization of participant responses, and 10 also included patient education (considered MI-consistent as long as it was offered together with active listening techniques). However, 10 of these 13 sessions also involved active problem solving, which was considered an MI-inconsistent technique for this patient group. With patients who had higher readiness for change, 11 of 16 sessions involved listening alone, 2 involved listening with education, and 3 involved listening with both education and action-oriented strategies, all of which were considered MI-consistent. Overall, the educator used MI-consistent techniques in all sessions, and used exclusively MI-consistent techniques in 19/29 sessions (66%).

Patient receipt of MI

Of 14 eligible patients, 12 (77%) agreed to be randomized; the two patients who did not agree were both African-American women, one aged 57 years and one over 80 years. Patients in the glaucoma educator condition had an average age of 57.9 years (standard deviation [SD] = 8.5), and 4 (50%) were male. Participants were 50% (4) white non-Hispanic and 50% (4) African-American. The demographics of the four patients randomly assigned to the control condition were similarly diverse: these participants had an average age of 55.5 years (SD = 14.7), 3 (75%) were male, and only 1 (25%) was white, with one Asian, one African-American, and one Pacific Islander participant in the control group. The demographics of patients randomly assigned to the glaucoma educator were more diverse than the total clinic population, where patients were 38% male and 78% white non-Hispanic. It is not known why the sample included more men and African-American patients, as these groups were not specifically targeted for recruitment. However, this finding does suggest that the glaucoma educator intervention was acceptable to a diverse patient group. Participants were selected specifically for nonadherence, which may be correlated with nonwhite race/ethnicity. Baseline nonadherence was high both for patients randomly assigned to the glaucoma educator (MEMS-based nonadherence on M = 36.7% of days per week, SD = 18.5) and for those assigned to the control condition (nonadherence on M = 37.0% of days per week, SD = 12.9).

The acceptability of MI to patients is illustrated by the following case vignette:

Mr S was a 52-year-old African-American man. His baseline adherence was 61%, and when offered a chance to speak with the glaucoma educator, he said he appreciated someone taking time to answer his questions. Mr S assumed he needed to take his medication “at bedtime,” which varied widely from day to day. Mr S also said that he was often tired and forgot to use his drops at night. The glaucoma educator used the “ask-tell-ask” method to teach Mr S about the importance of dosing every 24 hours, and that the time of day was flexible. Mr S expressed frustration that no one had explained this to him before, and the glaucoma educator validated Mr S’s desire to manage his own treatment more effectively. Mr S offered his own solution of taking medication at 8 pm as opposed to “at bedtime.” Further contacts helped Mr S to maintain this static time strategy and to overcome difficulties with forgetting. Based on these changes, Mr S improved his adherence to 95% by the end of 3 months of contact with the glaucoma educator. Mr S said he was very satisfied with the new therapeutic dosing regimen and with the assistance he received from the educator.

Of the eight patients randomly assigned to the glaucoma educator, all eight completed at least two sessions. On average, participants received 4.5 (SD = 1.85, 95% confidence interval [CI]: 2.95, 6.05) of six planned contacts, including 2.25 (SD = 0.89) in-person and 2.0 (SD = 0.93) telephone contacts. In-person sessions lasted 30–45 minutes, and telephone sessions lasted 5–10 minutes. Attrition was 4/8 (50%) over 6 months. Older patients were more likely to attrit, r = 0.52, and more African-American (75%) than white participants (25%) did not complete the full 6-month intervention. Two of the four participants who dropped out stated that they were unwilling to make further study-related clinic visits in the absence of incentives, and the other two participants were lost to follow-up due to a lack of stable contact information – both of these patients had disconnected phones and also failed to return for usual care. In one case, the participant was sent a registered letter, which was also not received. However, no participants reported any adverse events, and no patients withdrew specifically because they were dissatisfied with the intervention.

Patient enactment

Patient behavior was analyzed using an intent-to-treat method, with all patients in the glaucoma educator condition included in analyses regardless of how many sessions they completed. Participants’ readiness for change and two measures of adherence were modeled as separate outcomes, each analyzed within persons based on the number of glaucoma educator sessions completed. Models corrected for moderate to high inter-correlation of data points within participants, intraclass correlation (ICC) = 0.49 for readiness, ICC = 0.75 for counselor-rated adherence, and ICC = 0.77 for MEMS-based adherence. Effects are reported as unstandardized betas on a 1–4 scale for readiness, and as 0–100 percentages for the two adherence measures. As shown in , participants’ readiness for change increased as more educator visits were completed. Participants’ adherence improved significantly over time based on MEMS data, with no significant change in counselor-rated adherence. MEMS are likely the more accurate measure, as counselor-rated adherence was initially higher and may have been biased by a ceiling effect due to inaccurate patient reporting of adherence.

Patient enactment of behavior change is illustrated by the following case vignette:

Ms D was a 60-year-old white female. Her baseline adherence was 75%, which she was surprised to learn during her first visit with the glaucoma educator. When asked how she felt about her current adherence, Ms D said she was disappointed, and that difficulty using her eye drops and forgetfulness were the primary reasons for her poor adherence. The glaucoma educator responded by asking about Ms D’s goals and past experiences. Ms D noted that she did take other medications successfully, even when traveling. She set a goal of >85% adherence for herself, and suggested that using eye drops at the same time as her other evening medications might help her to remember them. The glaucoma educator agreed to a test of this plan. Over 3 months of follow-up contact, the glaucoma educator also helped Ms D problem-solve difficulties in administering eye drops by finding a technique that worked for her. Ms D was able to improve her adherence to 100% by the end of the program. Over time, it also emerged that Ms D had not strongly believed treatment was beneficial; the glaucoma educator helped her to explore this ambivalence, and by the conclusion of the program Ms D said that conversations with the educator had helped her to see the importance of taking medication correctly.

Discussion

Medication nonadherence is a barrier to successful glaucoma treatment that is not systematically addressed in most ophthalmology practices. The current study demonstrated that an in-person and telephone glaucoma educator intervention was feasible for implementing MI, a research-based health behavior change counseling technique, in a busy ophthalmology practice. Using an intervention manual and clinical support tools developed by a multidisciplinary expert group, a glaucoma educator was trained to implement MI with nonadherent patients. The educator had no initial exposure to MI, but reported that the method was relatively easy to learn. After individual training and self-study, his self- and instructor-rated competence with these methods improved from novice to skilled. Session rating forms showed that all of his interventions used MI-consistent techniques, but that he over-used problem-solving techniques with participants who were not yet ready for change. This is a common issue among providers new to MI, and additional training on matching techniques to patients’ readiness for change might improve these results. However, research also shows that multiple counselor behaviors may be appropriate, as long as they are delivered in the patient-centered “spirit” of MI.Citation31

Ophthalmology patients were willing to participate in the educator intervention. Participants’ demographics were more diverse than the overall population served by this clinic, indicating that the intervention was acceptable to a broad range of glaucoma patients. Half of patients dropped out early, so attrition was a significant limitation to MI’s feasibility in this study. The requirement of <80% baseline adherence may have resulted in a particularly nonadherent sample who were more difficult to retain over time. Two of the four participants lost to follow-up had their phone numbers disconnected and left care completely at the time they dropped out of the study. Although 50% attrition over six planned contacts is not unusual for psychosocial interventions, Citation38 it was considered quite high for this ophthalmology practice. Despite the high attrition rate, all participants received at least two of six planned contacts, which was considered an adequate dose of the intervention because even brief MI is efficacious.Citation14

Given that the intervention was successfully implemented and acceptable to patients, a final question is whether participants were able to enact recommended changes. Participants showed nonsignificant improvement in readiness for change and significant improvement in MEMS-based adherence over the course of the intervention, although there was no change on counselor-rated adherence. Whether these changes represented improvements over standard care is an efficacy question not addressed in the current study.

Potential challenges to widespread adoption of the glaucoma educator intervention in ophthalmology practice include staffing the educator position and integrating behavior change techniques with other aspects of medical care. Although in this study ophthalmologists were masked to the educator intervention, in actual practice the educator would be in regular contact with the patient’s ophthalmologist. This might enhance benefits of the intervention due to better coordination of care, or might reduce its effects if patients are less honest or less able to develop a working relationship with the glaucoma educator.

Cost of the educator position is another potential concern. However, if a glaucoma educator improves adherence and reduces long-term costs (eg, due to reduced vision loss, hospitalization, or need for long-term care), then a case could be made to insurers and other stakeholders that this service should be reimbursed. Health and behavior CPT codes exist to categorize patient counseling for chronic disease self-management, so an effective billing mechanism is not the issue, only whether adherence counseling should be a covered benefit. Cost-effectiveness analyses are therefore an important focus for future work.

Limitations and directions for future research

This study found that a glaucoma educator intervention was feasible in one outpatient ophthalmology practice. A small sample size and single clinic setting are important limitations to the generalizability of results. The two participating ophthalmologists were already aware of the problem of glaucoma medication nonadherence and committed to finding solutions. Implementation may be more difficult in settings where ophthalmologists are less aware of or interested in addressing nonadherence. Results showed that a newly trained glaucoma educator was relatively successful in delivering MI-consistent interventions although he also delivered some MI-inconsistent interventions. Conclusions about the actual content of glaucoma educator interventions would be strengthened in future studies by incorporating an independent expert’s ratings of session tapes or transcripts using an objective behavioral coding system such as the Motivational Interviewing Skills Code,Citation39 in addition to the glaucoma educator’s report.

Measurement is a universally acknowledged limitation in adherence studies, and the current investigation was no exception. The use of multiple measures is recommended because there is no “gold standard” for adherence.Citation36 Although we used two independent measures of adherence – MEMS and clinical interview – that have each been used in past research and are supported by psychometric data, the two measures did not always agree. In our study, adherence based on MEMS tended to be lower than educator-rated adherence. This may in part explain the finding that adherence improved based on MEMS data only, because MEMS-based adherence had more room to improve. This finding also highlights health care providers’ challenges in making accurate judgments about adherence: Recent research suggests that ophthalmologists detect nonadherence in less than 30% of cases where the patient is actually nonadherent.Citation25 Both adherence measures in this study assessed only the percentage of days on which patients took the correct number of doses; because glaucoma medications have short half-lives and the timing of doses is also important, more fine-grained MEMS-based adherence measures of dose timing may be desirable in future research.

Although participants were aware that MEMS were being used to monitor their adherence, research in other fields suggests that participants are more likely to misrepresent their adherence verbally than to deliberately falsify data by opening MEMS devices without taking medication.Citation35 MEMS may produce some improvement in adherence and of themselves, but this study’s 2-month run-in period helped to ensure that any patients who improved their adherence due to mere measurement effects were excluded prior to the start of the intervention. Nevertheless, unobtrusive adherence measures such as pharmacy fill data would strengthen further research by eliminating concerns about measurement effects.

Attrition was an important limitation to conclusions about patients’ receipt and enactment of MI. It is important to note that African-American patients were more likely to drop out, and also have been found to have lower adherence in previous research.Citation11 Based on analyses that included all available data from both patients who completed the full intervention and those who dropped out, patients increased their motivation and adherence while participating in the educator program, but this finding requires replication.

Finally, this feasibility study was not designed to prove that improvements in adherence were causally related to the educator program. Attrition, history effects, maturation, regression to the mean, or other artifacts are potential competing explanations. The current study also was not designed to differentiate the specific effects of MI from those that might be achieved by mere attention from a glaucoma educator. These limitations will be most effectively addressed in future work comparing participants’ results to a randomized control group.

Implications for practice

Glaucoma medications improve long-term outcomes, but patients find adherence difficult, and nonadherence increases the chance of disease progression. Following the lead of other medical specialties, the authors adopted a team approach to improve adherence. A glaucoma educator supported patients over time using MI. Working with local health behavior experts facilitated the integration of MI into ophthalmology practice. Although experts in using MI to promote adherence may not be available in all clinical settings, many community-based mental health practitioners have expertise in this approach and an interest in integrating psychological counseling into medical settings.Citation41 To identify mental health professionals with relevant expertise, US ophthalmologists can consult online listings at http://www.findapsychologist.org/ or http://www.therapytribe.com/, or find their local community mental health center at http://mentalhealth.samhsa.gov/databases/.

In this study, MI techniques were successfully learned and delivered by a glaucoma educator with no prior training in patient counseling methods. Not all practices may be able to afford or implement a separate glaucoma educator position. Training ophthalmologists themselves to use MI might be another option, although one that was not evaluated in this study. Some evidence does suggest that ophthalmologists can learn a more patient-centered counseling style and that it improves their ability to detect nonadherence.Citation40 However, because physician time is more expensive than nonphysician time and not all ophthalmologists may want to change their counseling style,Citation7,Citation25 feasibility may be greater when MI is provided by a separate educator. Patients also may be more honest with nonphysician health care providers.Citation42

The current study delivered MI only to a subgroup of patients selected for poor adherence based on MEMS data during a 2-month run-in period. This procedure limits generalizability of the findings to nonadherent glaucoma patients only. In general practice, it would be preferable to offer MI proactively to all patients prescribed glaucoma medication rather than offering support only after nonadherence occurs. This is especially true because almost 50% of patients with glaucoma are nonadherent,Citation6 and ophthalmologists have difficulty detecting nonadherence.Citation25

Participants received a moderate dose of MI over 6 months, although there were some problems with the match between counseling strategies and participants’ readiness for change. Attrition was also a potential problem, with a sample that was selected specifically for nonadherence and a higher percentage of African-American than white participants leaving the educator intervention early. Nevertheless, all participants received an adequate dose of MI based on prior meta-analytic findings.Citation14 Furthermore, MI was associated with increased readiness for change and improved adherence, and patient counseling in general has a significant dose-response effect,Citation43 so multiple patient contacts are still recommended for MI interventions despite this study’s high attrition rate. Overall, MI counseling delivered by a glaucoma educator appears to be a feasible adherence intervention in ophthalmology practice.

Acknowledgments

This study was sponsored by the American Glaucoma Society through an unrestricted educational grant from Pfizer. The authors wish to thank Courtney Lupia-Blasi for assistance with data entry and validation.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- HymanLWuSYConnellAMPrevalence and causes of visual impairment in the Barbados Eye StudyOphthalmology2001108101751175611581045

- QuigleyHANumber of people with glaucoma worldwideBr J Ophthalmol19968053893938695555

- FriedmanDSWolfsRCColmainBJPrevalence of open-angle glaucoma among adults in the United StatesArch Ophthalmol2004122453253815078671

- QuigleyHAVitaleSModels of open-angle glaucoma prevalence and incidence in the United StatesInvest Ophthalmol Vis Sci199738183919008633

- MeichenbaumDCTurkDFacilitating Treatment Adherence: A Practitioner’s GuidebookNew York, NYPlenum Press1987

- OkekeCOQuigleyHAJampelHDAdherence with topical glaucoma medication monitored electronically: the Travatan Dosing Aid StudyOphthalmology2009116219119919084273

- GelbLFriedmanDSQuigleyHAPhysician beliefs and behaviors related to glaucoma treatment adherence: the glaucoma adherence and persistency studyJ Glaucoma200817869069819092468

- KhandekarRShamaMEMohammedAJNoncompliance with medical treatment among glaucoma patients in Oman – a cross-sectional descriptive studyOphthalmic Epidemiol200512530330916272050

- FriedmanDSHahnSRGelbLDoctor-patient communication, health-related beliefs, and adherence in glaucoma: results from the glaucoma adherence and persistency studyOphthalmology200811581320132718321582

- ReesGLeongOCrowstonJGLamoureuxELIntentional and unintentional nonadherence to ocular hypotensive treatment in patients with glaucomaOphthalmology2010117590390820153902

- FriedmanDSOkekeCOJampelHDRisk factors for poor adherence to eyedrops in electronically monitored patients with glaucomaOphthalmology200911661097110519376591

- HaynesRBYaoXDeganiAKripalaniSGargAMcDonaldHPInterventions for enhancing medication adherenceCochrane Database Syst Rev200510194CD00001116235271

- RollnickSMillerWRButlerCCMotivational Interviewing in Health Care: Helping Patients Change BehaviorNew York, NYGuilford2007

- BurkeBLArkowitzHMencholaMThe efficacy of motivational interviewing: a meta-analysis of controlled clinical trialsJ Consult Clin Psychol200371584386114516234

- RubakSSandboekALauritzenTChristensenBMotivational interviewing: a systematic review and meta-analysisBr J Gen Pract200555430531215826439

- HechtJBorrelliBBregerRKRDeFrancescoCErnstDResnicowKMotivational interviewing in community-based research: experiences from the fieldAnn Behav Med200529 Suppl293415921487

- BatikOPhelanEAWalwickJAWangGLoGerfoJPTranslating a community-based motivational support program to increase physical activity among older adults with diabetes at community clinics: a pilot study of physical activity for a lifetime of success (PALS)Prev Chron Dis [serial on the Internet]2008517 http://www.cdc.gov/pcd/issues/2008/jan/pdf/07_0142.pdfAccessed Jun 10, 2010

- WeinsteinPHarrisonRBentonTMotivating mothers to prevent caries: confirming the beneficial effect of counselingJ Am Dental Assoc20061376789793

- CookPFAdherence to medicationsO’DonohueWTLevenskyERPromoting Treatment Adherence: A Practical Handbook for Health Care ProvidersThousand Oaks, CASage2006183202

- CookPFEmiliozziSMcCabeMTelephone counseling to improve osteoporosis treatment adherence: an effectiveness study in community practice settingsAm J Med Qual200722644545618006425

- CookPFEmiliozziSWatersCEl-HajjDEffects of telephone counseling on antipsychotic adherence and ED utilizationAm J Manag Care2008141284184619067501

- CookPFMcCabeMMEmiliozziSPointerLTelephone nursing intervention improves adherence to medication for HIVJ Assoc Nurses AIDS Care200920431632519576548

- CookPFEmiliozziSEl-HajjDMcCabeMMTelephone nurse counseling for medication adherence in ulcerative colitis: a preliminary studyPatient Educ Couns Epub 2010 Jan 13

- MillerWRRoseGSToward a theory of motivational interviewingAm Psychol200964652753719739882

- FriedmanDSHahnSRQuigleyHADoctor-patient communication in glaucoma care: Analysis of videotaped encounters in community-based office practiceOphthalmology2009116122277228519744715

- ProchaskaJOProchaskaJMWhy don’t continents move? Why don’t people change?J Psychother Integr19999183102

- BookHESome psychodynamics of non-complianceCan J Psychiatry19873221151173567818

- ResnickBBellgAJBorrelliBExamples of implementation and evaluation of treatment fidelity in the BCC studies: where we are and where we need to goAnn Behav Med200529 Suppl465415921489

- BellgAJBorrelliBResnickBEnhancing treatment fidelity in health behavior change studies: Best practices and recommendations from the NIH Behavior Change ConsortiumHealth Psychol200423544345115367063

- MillerWRRollnickSMotivational Interviewing2nd edNew York, NYGuilford2002

- MoyersTBMillerWRHendricksonSMLHow does motivational interviewing work? Therapist interpersonal skill predicts client involvement within motivational interviewing sessionsJ Consult Clin Psychol200573459059816173846

- CookPFFriedmanRLordABradley-SpringerLAOutcomes of multi-modal training for healthcare professionals at an AIDS Education and Training CenterEval Health Prof200932132219131377

- ProchaskaJONorcrossJDiClementeCChanging for GoodNew YorkAvon Books1995

- SchwartzGFCompliance and persistency in glaucoma follow-up treatmentCurr Opin Ophthalmol200516211412115744142

- LuMSafrenSASkolnikPROptimal recall period and response task for self-reported HIV medication adherenceAIDS Behav2008121869417577653

- ChesneyMAThe elusive gold standard: future perspectives for HIV adherence assessment and interventionJ Acquir Immune Defic Syndr200643 Suppl 1S149S15517133199

- MillerWRYahneCEMoyersTBMartinezJPirritanoMA randomized trial of methods to help clinicians learn motivational interviewingJ Consult Clin Psychol20047261050106215612851

- HansenNBLambertMJFormanEMThe psychotherapy dose-response effect and its implications for treatment delivery servicesClin Psychol Sci Pract200293329343

- MoyersTMartinTCatleyDHarrisKJAhluwaliaJSAssessing the integrity of motivational interviewing interventions: reliability of the Motivational Interviewing Skills CodeBehav Cogn Psychother2003312177184

- HahnSRFriedmanDSQuigleyHAEffect of patient-centered communication training on discussion and detection of nonadherence in glaucomaOphthalmology201011771339134720207417

- ClayRA new vision for American health careAPA Monitor200940416

- ValentiWMTreatment adherence improves outcomes and manages costsThe AIDS Reader2001112778011279875

- LambertMJArcherAResearch findings on the effects of psychotherapy and their implications for practiceGoodheartCDKazdinAESternbergRJEvidence-Based Psychotherapy: Where Practice and Research MeetWashington, DCAmerican Psychological Association2006111130