Abstract

Purpose

To determine the prevalence of color vision deficiency (CVD) among first-cycle students of the Faculty of Medicine and Biomedical Sciences of the University of Yaoundé I.

Patients and methods

A cross-sectional descriptive study was carried out between October 1, 2015 and May 31, 2016. Distant visual acuity was measured and color vision test done for all consenting students. Ishihara’s plates were used to test all the participants. Those who failed the test were tested with the Roth’s 28 Hue test for confirmation of CVD and classification.

Results

A total of 303 students were included, among whom 155 were males (50.8%) and 148 were females (49.2%). The mean age was 20.2±2 years. Five students (1.6%) failed the Ishihara’s plate testing. Roth’s 28 Hue test confirmed CVD in 4 of those cases, giving a prevalence of 1.3%. There were equal numbers of protan and deutan CVD.

Conclusion

Despite its low prevalence among first-cycle students of the Faculty of Medicine and Biomedical Sciences, CVD screening should be performed in order to raise awareness, which will go a long way to help orientate the choice of future specialty.

Introduction

Color vision deficiency (CVD) is a condition characterized by disturbances of color perception that occurs if the amount of visual pigment per cone is reduced or if 1 or more of the 3 cone systems are absent. Normal vision is trichromatic. Dichromats have 2, instead of the normal 3 cone photopigments. Anomalous trichromats have 3, usually only 1 of which is abnormal. CVDs are either congenital or acquired. The transmission of congenital red–green deficiencies (protan and deutan) is X-linked recessiveCitation1 and that of blue deficiency (tritan) is autosomal dominant.Citation2 Congenital tritan deficiency is a rare entity.Citation3 The prevalence of CVD in European Caucasians is about 8% in men and 0.4% in women.Citation4 A study among school children in our setting found a prevalence of 4.28%.Citation5 Variations exist among different ethnic populations.

Color vision plays an important role in health care, as some medical signs are based on changes in color. Medical doctors with CVD can find difficulties in their practice.Citation6 These difficulties include identifying signs such as pallor, jaundice, and red rashes.Citation7 There is, therefore, a risk in patient safety from possible diagnostic errors. The ability to identify and outline colored clinical signs has also been shown to be significantly less in practitioners with CVD compared with those without CVD.Citation8 Color vision is also important in dentistry for color and shade selection in the field of esthetic restorative dentistry. Color-defective dental personnel make significantly greater errors than color-vision normal dental personnel.Citation9

Medical students with CVD have been shown to have more problems in interpreting color-dependent clinical and laboratory photographs.Citation8,Citation10 This may lead to difficulties in learning histology, pathology, hematology, microbiology, dermatology, pediatrics, medicine, and ophthalmology. Such difficulties may lead to failure in examination and difficulty in medical practice later on.

Most of the time, people with CVD are unaware of their deficiency. Physicians who are aware of their deficiency report taking special care in clinical practice by devising strategies to overcome their disability.Citation7 Patel et alCitation11 reported a prevalence of CVD of 1.8% among medical students in India, while Pramanik et alCitation12 reported a prevalence of 5.58% among health science students in Nepal. To the best of our knowledge, no such study has been carried out in our setting. The aim of this study was to determine the prevalence of CVD among first-cycle students of the Faculty of Medicine and Biomedical Sciences (FMBS) of University of Yaoundé 1, in order to raise awareness in those with CVD. Awareness of CVD will lead to a reduction in anxiety during learning and may guide in choice of specialty.

Patients and methods

We carried out a cross-sectional and descriptive study between October 1, 2015 and May 31, 2016. Our study was reviewed and approved by the Institutional Ethical Clearance Committee of the FMBS of the University of Yaoundé I. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants. Sampling was consecutive and exhaustive.

Participants were first-cycle students of the FMBS who were enrolled into medicine, dentistry, and pharmacy courses for the 2015/2016 academic year following a competitive entrance examination. A self-filled questionnaire was given to the participants to obtain sociodemographic data and past history. Distant visual acuity was measured. Those who had used medications that are potentially toxic for the retina or the optic nerve and those with a visual acuity of <0.2 were excluded. The Ishihara 38 plate edition was used for screening CVD. If a participant missed the demonstration plate, the test was discontinued. Plates 2–21 were used for screening red–green defects, and plates 22–25 were for protan and deutan classification.

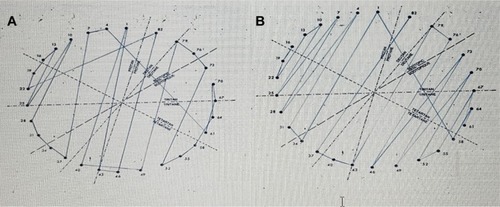

The participant was instructed to read the numbers in each plate within 3 seconds. The plates were held at a distance of 75 cm perpendicular to the line of sight under daylight illumination. A pass of the Ishihara test was the ability to read all plates correctly or an incorrect response in 3 or less plates. Those with 4 or more errors performed the Roth’s 28 Hue test for confirmation and differentiation of dichromats from anomalous trichromats. Each participant had to arrange the 27 caps in a circular sequence with respect to the fixed reference cap. They were allowed to alter the sequence prior to completion, and the test was to be completed in a maximum of 10 minutes. Scoring was accomplished by plotting the order of the caps on the diagram showing correct cap positions on the score sheet. Lines connecting the caps in their actual order were drawn.

If the lines remained along the circumference of the circle, the participant was deemed to be “normal”. If the sequence lines crossed the center repeatedly, the patient had a CVD. The type of defect was determined by comparing these crossover lines to see if they were parallel to the known color confusion axes. Considering the similarity between the Roth 28 Hue test and the Fansworth D-5 test, those with at least 6 crossover lines were considered dichromats.Citation13

Results

Among the 303 students enrolled and tested, there were 155 males (50.8%) and 148 females (49.2%). The mean age was 20.2±2 years. Most of them were Cameroonians (99.3%; n=301). There were only 2 foreigners: 1 Chadian and 1 Rwandan. Students enrolled in medicine were the most represented (50.5%; n=153). Those enrolled in dentistry and pharmacy represented 33.7% and 15.8%, respectively.

Five students (1.7%), all of them Cameroonians, had 4 or more errors on the Ishihara screening test. All of them were males (). These students were tested using the Roth 28 test. One was normal, and 4 were confirmed with CVD (), giving a prevalence of 1.3% (95% CI: 0.0051–0.0334). Two were deutans and 2 were protans. No case of total color blindness was detected. The prevalence was 1.96% (n=3/153) among medical students and 0.98% (n=1/102) among dentistry students. No case of CVD was found (n=0/48) among pharmacy students. None of them were conscious of difficulties in identifying colors and none had ever taken a color vision test before.

Table 1 Distribution of the Ishihara test results according to sex

Discussion

The prevalence of CVD varies depending on race and ethnicity. The prevalence in this study is similar to that reported by Patel et alCitation11 in medical students in India; 1.8%. A higher prevalence of 5.58% was reported in Nepal among male medical and dental students.Citation12 This can be attributed to racial differences in the prevalence of CVDs. Higher prevalences are documented among other races compared with African populations.Citation4

Red–green perceptive disorders are X-linked recessive, and thus are seen more frequently in males than in females.Citation11 No case of CVD in a female was found in our study. Mughal et alCitation14 in Pakistan reported a higher prevalence among female students. They concluded that more research is needed to explore the problem.

Medical doctors with mild CVD report less difficulties in their practice than those with severe forms.Citation6 Poole et al,Citation15 in a study on CVD among histopathologists, found that those with severe deficiency made significantly more mistakes on interpreting histopathology slides. Screening medical students offers them the possibility to become aware about CVD and to become alert during the identification of signs while examining patients or laboratory slides.

There were equal numbers of protan and deutan CVD, giving a protan:deutan ratio of 1. A ratio of 1.1:1 was reported by Ugalahi et alCitation16 in a study on the prevalence of CVD among secondary school students in Ibadan, South-West Nigeria. Among medical students, Pramanik et alCitation17 found that 57.0% were protanopic, while 43.0% were deuteranopic. Other studies, however, report a higher proportion of deutansCitation6,Citation11,Citation12 or absent protanomalous deficiencies.Citation18 Genetic variations in various populations may explain the difference.

No student with CVD in our study was aware of his deficiency. Tagarelli et alCitation18 found that 96% of students attending middle school and 65% of students at university were not aware of their anomaly. Screening during school years would help affected students to choose their future professional orientation. Advice and support are necessary for students with CVD as awareness leads to the development of strategies to overcome this condition. Strategies to overcome difficulties described by medical doctors with CVD include paying special attention to history, close observation, or asking for help from other colleagues.Citation6

Conclusion

The prevalence of CVD among first-cycle students of FMBS was 1.3%. Although color vision screening is not a regulatory requirement, we recommend it in first-year students to raise awareness in those with CVD and to advise them accordingly. This will lead to the recognition of their limitation and avoid anxiety during training, as they will devise ways of overcoming CVDs and other such limitations.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- DeebSSMolecular genetics of color-vision deficienciesVis Neurosci200421319119615518188

- HenryGHColeBLNathanJThe inheritance of congenital tritanopia with the report of an extensive pedigreeAnn Hum Genet1963273219231

- KrillAESmithVCPokornyJFurther studies supporting the identity of congenital tritanopia and hereditary dominant optic atrophyInvest Ophthalmol19711064574655314165

- BirchJWorldwide prevalence of red-green color deficiencyJ Opt Soc Am A Opt Image Sci Vis201229331332022472762

- Ezangono NdoMMProfil épidémiologique des dyschromatopsies héréditaires chez les enfants des trois écoles primaires de la ville de Douala [Epidemiological profile of congenital color vision deficiencies in children attending three primary schools in the city of Douala]MD [Thesis]YaoundeUniversity of Yaounde I2010

- SpaldingJAMedical students and congenital colour vision deficiency: unnoticed problems and the case for screeningOccup Med1999494247252

- CampbellJLSpaldingJABMirFAThe description of physical signs of illness in photographs by physicians with abnormal colour visionClin Exp Optom2004874–533433815312036

- CampbellJLGriffinLSpaldingJABMirFAThe effect of abnormal colour vision on the ability to identify and outline coloured clinical signs and to count stained bacilli in sputumClin Exp Optom200588637638116329745

- DavisonSPMyslinskiNRShade selection by color vision-defective dental personnelJ Prosthet Dent1990631971012295995

- DhingraRRohatgiJDhaliwalUPreparing medical students with congenital colour vision deficiency for safe practice [Internet]Natl Med J India [cited September 10, 2017]. Available from: http://www.nmji.in/article.asp?issn=0970-258X;year=2017;volume=30;issue=1;spage=30;epage=35;aulast=DhingraAccessed May 6, 2018

- PatelJRTrivediHPatelAPatilSJethvaJAssessment of colour vision deficiency in medical studentsInt J Community Med Public Health201631230235

- PramanikTKhatiwadaBPanditRColor vision deficiency among a group of students of health sciencesNepal Med Coll J201214433433624579547

- VisionNRC(US) C on Color vision tests [Internet]Washington, DC (US)National Academies Press1981 [cited September 15, 2017]. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK217823/Accessed May 6, 2018

- MughalIAAliLAzizNMehmoodKAzalNColour vision deficiency (CVD) in medical studentsPak J Physiol2013911416

- PooleCJHillDJChristieJLBirchJDeficient colour vision and interpretation of histopathology slides: cross sectional studyBMJ19973157118127912819390055

- UgalahiMOFasinaOOgunOAAjayiBGPrevalence of congenital colour vision deficiency among secondary school students in Ibadan, South-West NigeriaNiger Postgrad Med J2016232939627424620

- PramanikTSherpaMTShresthaRColor vison deficiency among medical students: an unnoticed problemNepal Med Coll J2010122818321222402

- TagarelliAPiroATagarelliGGenetic, epidemiologic and social features of colour blindnessCommunity Genet199921303515178960