Abstract

Purpose:

To present various forms of uveitis and/or retinal vasculitis attributed to Bartonella infection and review the impact of this microorganism in patients with uveitis.

Methods:

Retrospective case series study. Review of clinical records of patients diagnosed with Bartonella henselae and Bartonella quintana intraocular inflammation from 2001 to 2010 in the Ocular Inflammation Department of the University Eye Clinic, Ioannina, Greece. Presentation of epidemiological and clinical data concerning Bartonella infection was provided by the international literature.

Results:

Eight patients with the diagnosis of Bartonella henselae and two patients with B. quintana intraocular inflammation were identified. Since four patients experienced bilateral involvement, the affected eyes totaled 14. The mean age was 36.6 years (range 12–62). Uveitic clinical entities that we found included intermediate uveitis in seven eyes (50%), vitritis in two eyes (14.2%), neuroretinitis in one eye (7.1%), focal retinochoroiditis in one eye (7.1%), branch retinal vein occlusion (BRVO) due to vasculitis in one eye (7.1%), disc edema with peripapillary serous retinal detachment in one eye (7.1%), and iridocyclitis in one eye (7.1%). Most of the patients (70%) did not experience systemic symptoms preceding the intraocular inflammation. Antimicrobial treatment was efficient in all cases with the exception of the case with neuroretinitis complicated by anterior ischemic optic neuropathy and tubulointerstitial nephritis.

Conclusion:

Intraocular involvement caused not only by B. henselae but also by B. quintana is being diagnosed with increasing frequency. A high index of suspicion is needed because the spectrum of Bartonella intraocular inflammation is very large. In our study the most common clinical entity was intermediate uveitis.

Introduction

The genus Bartonella includes more than 20 species, of which the members are small Gram-negative, fastidious, hemotropic, intracellular bacteria belonging to the α-2 subdivision of proteobacteria. These bacteria can cause a long-lasting intraerythrocytic bacteremia in their mammalian reservoir hosts and are mainly transmitted by bloodsucking arthropod vectors.Citation1 Several Bartonella species have been identified to cause human diseases. In this article we will focus on Bartonella henselae, Bartonella quintana and their ocular manifestations, mainly the intraocular ones (uveitis and/or retinal vasculitis), with regard to our cases and data provided by the international literature. B. henselae has been most commonly implicated in intraocular inflammation, especially recently, and there are reports concerning various forms of intraocular inflammation ().

Table 1 Bartonella species found to cause systemic and ocular manifestations

Bartonella henselae

The major host reservoir for B. henselae is cats.Citation2 Many seroepidemiological studies have been published showing the worldwide distribution of B. henselae infection in cats. The antibody prevalence in cats varies from between 5%–10% up to 70%–80% depending on the geographical area tested and the domestic or stray cat status.Citation3–Citation9 B. henselae causes intraerythrocytic bacteremia in cats for several weeks, but usually cats are asymptomatic. Transmission between cats depends on the arthropod vector Ctenocephalides felis, or the cat flea.Citation10 B. henselae can multiply within the digestive system of the cat flea and survives several days in the flea feces. The main source of infection for cats and also humans seems to be the inoculation of flea feces by contaminated cat claws with a cat scratch.Citation1 Transmission to humans can also happen with cat biting or cat saliva through an open wound. The cat flea bite is probably another way of transmission to humans as well. Other possible vectors for B. henselae infection are ticks and biting flies.Citation1 Dogs can be infected with B. henselae as well, but the role of dogs as reservoir hosts is less clear than cats.Citation11

B. henselae causes a variety of manifestations in humans and the response depends on their immune status. In immunocompetent individuals the response is granulomatous and suppurative. In immunocompromised patients the response is mainly vasoproliferative.Citation12

In immunocompetent individuals there is a wide spectrum of clinical manifestations:

Typical cat scratch disease is the most common manifestation. After a cat scratch at the site of the inoculation a papule or pustule is formed and there is a regional lymphadenopathy with or without fever. The affected nodes may become suppurative.Citation13

Fever of unknown origin (FUO). Prolonged fever >2 weeks without any symptoms or signs of an obvious clinical disease.Citation14

Ocular manifestations: Parinaud oculoglandular syndrome consists of follicular conjunctivitis and regional lymphadenopathy. Posterior segment manifestations include neuroretinitis, focal retinitis, choroiditis or retinochoroiditis, multifocal retinitis, choroiditis or retinochoroiditis, intermediate uveitis, branch retinal artery and vein occlusions, vasculitis and angiomatous vasoproliferative lesions that are rare and mostly seen in immunocompromised patients.Citation15,Citation16

Other clinical manifestations

Hepatosplenic manifestations: Granulomatous and suppurative disease of the liver and spleen with systemic symptoms as prolonged fever and with or without abdominal pain, hepatomegaly or splenomegaly.Citation17

Cardiovascular manifestations: Endocarditis is the most common cardiac complication. Bartonella species are responsible for about 3% of cases of endocarditis.Citation18,Citation19 Myocarditis is a rare complication.

Neurologic manifestations: They are rare and include encephalopathy, seizures, status epilepticus, meningitis, meningoencephalitis, peripheral facial nerve paralysis, coma, transverse myelitis and acute hemiplegia.Citation20–Citation22

Hematologic manifestations: They are rare and include hemolytic anemia and thrombocytopenic purpura.

Renal manifestations: Glomerulonephritis is a rare complication.Citation23

Orthopedic manifestations: Osteomyelitis and arthritis are rare complications.Citation24,Citation25

Pseudomalignancy: Simulating lymphoma, mimicking breast tumor, simulating a malignant process of the chest wall, simulating rhabdomyosarcoma, mimicking parotid malignancy.Citation26–Citation30

In immunocompromised patients the response is mainly vasoproliferative:

Bacillary angiomatosis: Refers to skin proliferative vascular lesions that may resemble Kaposi’s sarcoma. Red or brown papules, angiomatous nodules, pedunculated lesions, or deep subcutaneous masses.Citation31,Citation32

Bacillary peliosis: Refers to proliferative vascular lesions in liver and spleen.Citation33

Bartonella quintana

The major reservoir hosts for B. quintana are humans. The disease is transmitted among humans by the human body louse, Pediculus humanus corporis. The human body louse lives on the body and in the clothes or bedding of its human host.Citation34 Seroepidemiological studies in homeless people living in poor conditions show an antibody prevalence that varies from 2% up to 57%.Citation35–Citation38 B. quintana can multiply within the digestive system of the louse and survives in louse feces. Transmission to humans occurs via inoculation of infectious louse feces through altered skin.Citation1 Lice cause local skin irritation because they inject biological proteins with their bites resulting in itching, scratching and inoculation of B. quintana. Transmission of B. quintana to a human has also been demonstrated to happen with a cat bite.Citation39 B. quintana has been found present in dogs, cats,Citation40 cat fleas and also monkeys.Citation41 Ticks could also be a possible vector.Citation11

Clinical manifestations

Trench fever. During World War I more than 1 million people were infected. After World War II the incidence of the disease was very low but recently the incidence increased in people living in poor conditions and occasionally infested by body lice such as the homeless, drug addicts and alcoholics. Trench fever is characterized by recurrent attacks of 5-day cycling fever, headaches and dizziness.Citation34,Citation42

Chronic bacteremia.

Endocarditis.Citation18

Bacillary angiomatosis, especially in immunocompromised individuals.Citation34,Citation42

Lymphadenopathy.

Ocular manifestations: neuroretinitis, anterior, intermediate and posterior uveitis.Citation43

Ocular manifestations of Bartonella infection

The most common ocular manifestation of B. henselae infection is Parinaud’s oculoglandular syndrome (POGS). The syndrome was named after Henri Parinaud who described it for the first time in 1889.Citation44 Nearly 5% of symptomatic patients with cat scratch disease have POGS.Citation13 Patients present with fever, granulomatous conjunctivitis and regional lymphadenopathy affecting the preauricular, submandibular or cervical lymph nodes. Typical symptoms include unilateral eye redness, foreign body sensation and epiphora.Citation15 Transmission is considered to happen through inoculation of contaminated flea feces from the hands to the eye, because direct cat scratches to the conjunctiva are unusual.Citation16 B. quintana has also been found in a case report to be the causative organism in a patient with POGS.Citation45

Neuroretinitis affects 1% to 2% of patients with B. henselae infection.Citation13,Citation46 There is optic nerve head swelling with complete or partial macular star formation. Among patients with neuroretinitis the most common cause is B. henselae and approximately two-thirds have positive serologic testing.Citation47 Patients present with unilateral, painless, sudden visual loss and systemic symptoms can also be present.Citation48 Bilateral neuroretinitis is rare and the simultaneous presence of neuroretinitis and POGS is also uncommon.Citation49,Citation50 Some patients with neuroretinitis also present with multifocal retinochoroiditis.Citation48 Optic disc edema associated with peripapillary serous retinal detachment can be an early sign of systemic B. henselae infection.Citation51 Usually after 2 to 4 weeks a macular star formation follows, but in some patients this may not happen. The macular exudates may take months to resolve. After the resolution of neuroretinitis, a mild optic neuropathy may persist. Some patients may have disc pallor, decreased contrast sensitivity, abnormal visually evoked potentials, dyschromatopsia and persistent afferent pupillary defects.Citation52 Other causes of neuroretinitis that should be included in the differential diagnosis are syphilis, tuberculosis, Lyme disease, toxoplasmosis, toxocariasis, leptospirosis, sarcoidosis, malignant hypertension, diabetes and increased intracranial pressure.Citation15,Citation16 B. quintana, B. grahamii and B. elizabethae have also been found to be causes of neuroretinitis.Citation53–Citation55

Other posterior segment manifestations of patients with B. henselae infection include focal or multifocal retinitis, choroiditis or retinochoroiditis with or without the presence of neuroretinitis or disc edema. Branch retinal artery and vein occlusions and serous retinal detachment, macular hole, panuveitis with diffuse choroidal thickening simulating Vogt–Koyanagi–Harada syndrome, vitritis, vasculitis and papillitis have been noted by several authors.Citation48,Citation56–Citation62 B. quintana and B. grahamii have been found to be causes of retinitis, vasculitis and papillitis.Citation43 B. grahamii has also been found to cause retinal vascular occlusion.Citation63

In immunocompromised patients with B. henselae infection, retinal bacillary angiomatosis and subretinal vascular mass have been observed.Citation64 Angiomatous lesions have also been observed in immunocompetent patients.Citation56 Anterior and intermediate uveitis can be seen in B. henselae and B. quintana infection.Citation43,Citation65 B. grahamii also can cause anterior uveitis.Citation43

Patients and methods

In a series of consecutive patients with intraocular inflammation (ie, uveitis, retinal vasculitis) examined and treated during the recent 10 years in the Ocular Inflammation Department of the University Eye Clinic of Ioannina (Greece), the implication of both B. henselae and B. quintana was also explored. In all patients, a meticulous diagnostic approach to inflammation was carried out, concerning infectious diseases (including brucellosis, tuberculosis, syphilis, toxoplasmosis, toxocariasis, leptospirosis, Lyme disease, bartonellosis and infection due to herpes simplex virus, herpes zoster virus, cytomegalovirus, Epstein–Barr virus and human immunodeficiency virus I+II), sarcoidosis and other autoimmune diseases, and specific idiopathic uveitic syndromes as well.

The diagnosis of a Bartonella infection was based on:

History of traumatic cat exposure (scratching and/or biting) or even licking through an open wound.

Serologic testing for B. henselae and B. quintana using indirect fluorescence assay (IFA). The laboratory examination of the sera was carried out at the Pasteur Institute of Athens. Titers < 1:32 were considered negative, titers of ≥ 1:64 were considered positive (high diagnostic value), titers = 1:32 were considered uncertain (moderate diagnostic value).Citation66 The sensitivity and specificity of the test depend on the serological cutoff value chosen. For a cutoff value = 1:32 (sensitivity = 0.80 specificity = 0.85). For a cutoff value of ≥ 1:64 (sensitivity = 0.70; specificity = 0.95). The best compromise between specificity and sensitivity is obtained with a cutoff value between 1:32 and 1:64.Citation66 In our cases with positive history of cat attack and absence of another diagnosis, the cutoff value 1:32 was considered as positive in order to avoid an underdiagnosis of Bartonella infection.

Presence of an intraocular inflammation not attributed to other causes.

Previous illness (preceding the intraocular inflammation).

Presence of human body lice.

Patients with a diagnosis of Bartonella intraocular inflammation were treated with the appropriate antibiotics (the main antibiotics used were doxycycline, rifampicin and azithromycin)Citation16 and were followed-up for the evaluation of the final outcome of the ocular disease and for any eventual systemic complication due to Bartonellosis.

Our results were compared to those of other authors with regard to the intraocular findings (anterior uveitis, intermediate uveitis, vitritis, neuroretinitis, choroiditis, retinal vasculitis and vascular occlusion), diagnostic approach, appropriate treatment and outcome. A thorough analysis of the data provided by the international literature regarding Bartonella ocular infections, with a particular focus on intraocular involvement, was carried out in order to obtain a profile of the manifestations of intraocular infection due to Bartonella species, and avoid underdiagnosis.

Results

Intraocular inflammation was attributed to Bartonella (either henselae or quintana) in 10 patients. This number constitutes 0.33% of the cases with uveitis examined in our department during the same period (last decade). presents the profile of patients with intraocular inflammation considered to be of Bartonella origin. Ages ranged from 12 to 62 years (mean age 36.6). In eight patients the causative organism was B. henselae. In seven of them there was a history of traumatic cat exposure (scratching and/or biting) and in one of them there was a history of cat licking through an open wound. In two patients the causative organism was B. quintana. In these two patients, one had pubic lice and the other was a worker in the fur industry, suggesting a possible tick or flea bite. Neither patient had a history of traumatic cat exposure.

Table 2 Profile of patients with intraocular inflammation considered of Bartonella origin

In our series of ten patients, six patients were male and four female. Four patients had bilateral involvement and there were 14 affected eyes. In terms of eye involvement the clinical findings were: intermediate uveitis in seven eyes (50%); vitritis in two eyes (14.2%); neuroretinitis in one eye (7.1%); focal retinochoroiditis in one eye (7.1%); branch retinal vein occlusion (BRVO) due to vasculitis in one eye (7.1%); disc edema with peripapillary serous retinal detachment in one eye (7.1%); and recurrent iridocyclitis in one eye (7.1%). The most common uveitic entity in our series of cases was intermediate uveitis. Since all patients with intermediate uveitis were young adults (27–41 years), neurological examination and MRI of the brain were carried out to rule out a multiple sclerosis background. The results were negative for multiple sclerosis.

The great majority of the cases (70%) did not experience a systemic or another ocular illness preceding the intraocular inflammatory manifestations (). Antimicrobial treatment was efficient in all cases with the exception of the case with neuroretinitis complicated by anterior ischemic optic neuropathy and tubulointerstitial nephritis (case 1). The main antibiotics administered in our cases were rifampicin, doxycycline and azithromycin. Ciprofloxacin and ceftriaxone were also used in cases with treatment failure, allergy and early side-effects. presents the visual acuities before and after treatment, the antibiotics used to eradicate the microorganism, and the complications seen during follow-up.

Table 3 Treatment and outcome in ten cases with intraocular inflammation due to B. henselae and B. Quintana

Case reports

Case 1

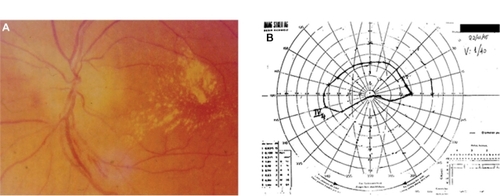

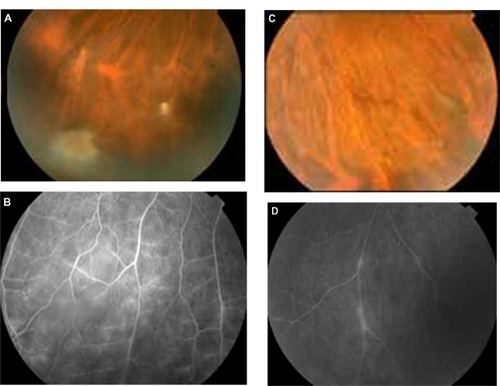

Sixty-year-old male with a history of cat scratching and without any systemic manifestations. In his left eye, neuroretinitis was observed 1 month after cat scratching (). The IgG titer for B. henselae was 1:32. The visual acuity in the affected left eye was 0.05 before treatment. The right eye was not affected. He was treated with ciprofloxacin 750 mg daily and doxycycline 100 mg 12 hourly for 4 weeks, followed by ceftriaxone 1 g 12-hourly for 1 week. The visual acuity after treatment was 0.025. This patient developed anterior ischemic optic neuropathy (AION) 3 weeks after the onset of disease (neuroretinitis) with characteristic visual field defect and had a poor outcome in spite of treatment (); in addition, tubulointerstitial nephritis occurred 3 months after the diagnosis of neuroretinitis suggesting possible tubulointerstitial nephritisuveitis (TINU) syndrome.Citation67 This patient had abnormal renal function with elevated serum creatinine. The urine analysis was abnormal showing low grade proteinuria, hematuria and increased beta-2 microglobulin. Also mild anemia (hemoglobin 12 g/dL) and an abnormal elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR 96 mm/hour) were noted. A renal biopsy was not performed and the patient was treated successfully with systemic corticosteroids for the renal disease. The final visual acuity of his left eye was counting fingers at 30 cm.

Case 2

Twelve-year-old girl with a history of cat scratch and fever 2 weeks later. Six weeks after the cat scratch, a focal retinochoroiditis was observed in her right eye. The IgG titer for B. henselae was 1:32. The visual acuity in the affected right eye was 0.5 before treatment. The left eye was not affected. She was treated with rifampicin 600 mg daily and doxycycline 100 mg 12 hourly for 4 weeks with complete resolution of the uveitis. The visual acuity after treatment in the affected right eye was 1.0. During the follow-up, a chorioretinal extrafoveal scar was observed in the location of the focal retinochoroiditis, which did not affect visual acuity.

Case 3

Thirty-one-year-old male with a history of cat scratching and biting and without any systemic symptoms. Bilateral vitritis was observed 6 weeks after cat scratching. The IgG titer for B. henselae was 1:64. The visual acuities before treatment in the affected eyes were 0.9 in the right eye and 0.8 in the left eye. He was treated with rifampicin 600 mg daily and azithromycin 500 mg daily for 4 weeks with complete resolution of the uveitis. The visual acuities after treatment were 1.0 in both eyes. One year after the onset of uveitis, the patient developed myocarditis,Citation68 not associated with another preexisting heart disease with regard to cardiological investigation. The medical history of the patient was also negative for other infectious diseases causing myocarditis.

Case 4

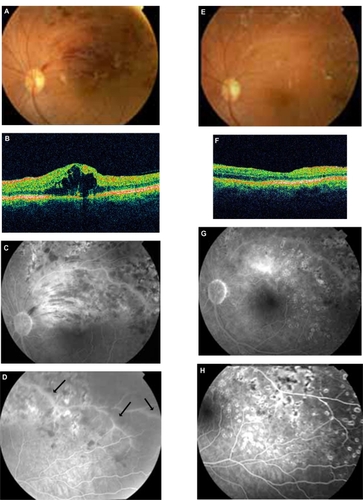

Thirty-six-year-old male with BRVO in his left eye and recurrence of macular edema after the treatment with laser photocoagulation and intravitreal bevacizumab (). A more meticulous medical history revealed a recent episode of cat scratching 4 weeks before the onset of BRVO without any systemic symptoms. In addition, pedantic analysis of fluorescein angiography features took into account along with the BRVO the presence of retinal phlebitis (). Therefore, a diagnostic approach for retinal vasculitis and laboratory examination of the serum for B. henselae and quintana was carried out. The IgG titer for B. henselae was 1:32. Visual acuity before treatment in the affected left eye was 0.8. He was treated with rifampicin 600 mg daily and azithromycin 500 mg daily for 4 weeks, resulting in an improvement of visual acuity and regression of macular edema (). The visual acuity after treatment in the affected left eye was 1.0. No recurrence either of macular edema or of retinal vasculitis was observed during a long follow-up period (2 1/2 years).

Figure 2 Patient 4 ( and ). A, B, C, D: BRVO along with cystoid macular edema (CME) in OCT and signs of vasculitis (FA arrows) treated previously with laser and intravitreal bevacizumab (positive serology for Bartonella henselae and history of cat scratch). E, F, G, H: After 4 weeks’ treatment with azithromycin and rifampicin, there is a significant improvement of fundus findings along with FA findings and total regression of CME (OCT).

Case 5

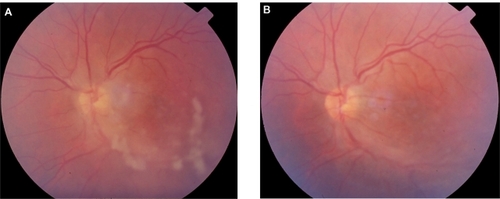

Thirty-year-old male with a history of cat scratching. At the site of inoculation a pustule was formed and after 6 weeks intermediate uveitis was observed in his left eye (). The IgG titer for B. henselae was 1:64. The visual acuity before treatment in the affected left eye was 0.5. The right eye was not affected. He was treated with ciprofloxacin 500 mg 12-hourly for 4 weeks with complete resolution of the intermediate uveitis (). The visual acuity after treatment in the affected left eye was 1.0. A late complication was noticed in the left eye during follow-up; an epiretinal membrane of the macula was observed and the final visual acuity was 0.9.

Case 6

Twenty-eight-year-old female with a history of cat scratching and without any systemic symptoms. Bilateral intermediate uveitis along with peripheral vasculitis was observed 5 weeks after cat scratching. The IgG titer for B. henselae was 1:32. The visual acuities in the affected eyes before treatment were 0.6 in the right eye and 0.8 in the left eye. She was treated with rifampicin 600 mg daily and doxycycline 100 mg 12-hourly for 4 weeks with complete resolution of the bilateral uveitis. The visual acuities after treatment in the affected eyes were 1.0 in both of them.

Case 7

Forty-one-year-old male with a history of cat scratching followed after 2 weeks by malaise along with POGS. Five weeks after cat scratching, bilateral intermediate uveitis along with peripheral vasculitis was observed. The IgG titer for B. henselae was 1:32. The visual acuities before treatment in the affected eyes were 0.7 in the right eye and 0.8 in the left eye. He was treated with rifampicin 600 mg daily and doxycycline 100 mg 12-hourly for 4 weeks with complete resolution of the bilateral intermediate uveitis. The visual acuities after treatment in the affected eyes were 1.0 in both of them. A late complication was noticed in the right eye during follow-up; an epiretinal membrane of the macula was observed and the final visual acuity was 0.8.

Case 8

Twenty-seven-year-old female with a history of pubic lice and without any systemic symptoms. She did not have a history of traumatic cat exposure. Bilateral intermediate uveitis along with peripheral vasculitis was observed (). The IgG titer for B. quintana was 1:128. The visual acuities before treatment in the affected eyes were 0.9 in the right eye and 0.9 in the left eye. She was treated with rifampicin 600 mg daily and doxycycline 100 mg 12-hourly for 4 weeks with complete resolution of the bilateral intermediate uveitis. The visual acuities after treatment in the affected eyes were 1.0 in both of them.

Figure 4 Patient with bilateral intermediate uveitis and peripheral vasculitis (increased IgG titers against B. quintana; patient 8 in and ). (A) and (B) right eye with snowballs masking the vessels with mild vasculitis in fluorescein angiography (FA), (C) and (D) the vasculitis is more prominent in left eye; in FA segmental periphlebitis is present.

Case 9

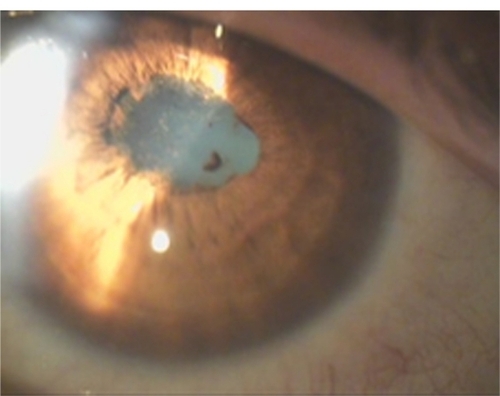

Thirty-nine-year-old female with a history of recurrent unilateral iridocyclitis. She had three recurrences of inflammation in her left eye in a period of 1 year before the examination in our department. The iridocyclitis was a nongranulomatous one with posterior synechiae (). She did not have any systemic symptoms. The IgG titer for B. quintana was 1:64. She was a worker in the furs elaboration industry, suggesting a possible tick or flea bite. She didn’t have a history of traumatic cat exposure. The visual acuity before treatment in the affected left eye was 0.8. The right eye was not affected. She was treated with doxycycline 100 mg 12-hourly and azithromycin 500 mg daily for 4 weeks with complete resolution of the uveitis. The visual acuity after treatment in the affected left eye was 1.0. There were no recurrences during the 3-year follow-up period. Because of cataract formation in the left eye during follow-up, the final visual acuity in the left eye was 0.9.

Case 10

Sixty-two-year-old male with a history of cat licking through an open wound and without any systemic symptoms. Optic disc edema associated with peripapillary serous retinal detachment was observed in his left eye 5 weeks after cat licking. The IgG titer for B. henselae was 1:128. The visual acuity before treatment in the affected left eye was 0.4. The right eye was not affected. He was treated with rifampicin 600 mg daily and doxycycline 100 mg 12-hourly for 4 weeks with complete resolution of the uveitis. Visual acuity after treatment in the affected left eye was 0.9.

Discussion

Our knowledge about Bartonella species has increased in the last few years and there are many reports about ocular manifestations of Bartonella infection. B. henselae has been found to cause POGS, neuroretinitis, retinochoroiditis, retinal vascular occlusions, vasculitis, vitritis, anterior uveitis, intermediate uveitis, posterior uveitis, papillitis and other ocular complications.Citation15,Citation16,Citation43,Citation46,Citation48,Citation56,Citation59 B. quintana has been found to cause POGS, neuroretinitis, retinitis, vasculitis, papillitis, anterior, intermediate and posterior uveitis.Citation43,Citation45,Citation53 B. grahamii has been found to cause retinitis, vasculitis, papillitis, retinal vascular occlusion, anterior and posterior uveitis.Citation43,Citation63 B. elizabethae has been found to cause neuroretinitis.Citation55 It is important in patients with these ocular manifestations to know if there is a history of traumatic cat exposure, the presence of systemic symptoms such as fever, headache, lymphadenopathy or the presence of body lice. Since uveitis seems to be an emerging clinical form of Bartonella infection, patients with uveitis of unknown etiology should be tested for Bartonella species.Citation43

The most common uveitic entity in our series of cases was intermediate uveitis. In the patients with intermediate uveitis snowballs and/or snowbanks were noted and three of them had bilateral involvement with peripheral vasculitis. There was also a patient with bilateral vitritis. According to the Standardization of Uveitis Nomenclature (SUN) working groupCitation69 vitritis is included in the clinical entity of intermediate uveitis. This means that the total number of affected eyes with intermediate uveitis was nine (64.2%). To our knowledge this is the first report of a series of cases of ocular bartonellosis in which intermediate uveitis is the prominent clinical entity. In other published series of cases, neuroretinitis associated with macular starCitation57 and isolated foci of retinitis or choroiditisCitation70 were the most common intraocular findings in cat scratch disease (CSD). In a recent study from two Brazilian uveitis reference centers the most common findings of CSD were retinal infiltrates and angiomatous lesions.Citation56 In another study that explored the implication of B. henselae, B. quintana and B. grahamii as causes of uveitis, the most common clinical entity found was posterior uveitis.Citation43 The spectrum of intraocular manifestations of Bartonella infection is very large and this must be kept in mind.

In our series of cases there was a patient who, 1 year after the onset of the ocular disease (bilateral vitritis), had the complication of myocarditis. There is a study that reports chronic active myocarditis after B. henselae infection. The mechanism is believed to be that of secondary lymphocyte mediated immune response.Citation71 This could also be the case in our patient.

The case of our patient who presented with neuroretinitis was complicated after 3 months with tubulointerstitial nephritis (possible TINU syndrome). The etiology of TINU syndrome remains unclear. TINU is thought in be an immune-mediated process and there are associations with some infectious agents, several drugs and toxins. However it can be idiopathic.Citation67 In our case, the possible TINU syndrome could be associated with B. henselae or the antibiotic treatment used to eradicate the microorganism. To our knowledge this is the first reported case of a possible association of Bartonella infection and TINU. The same patient also developed AION before the onset of interstitial nephritis. Those sequential events following neuroretinitis could suggest an immune associated mechanism triggered by Bartonella infection.

There are recent reports of anterior uveitis caused by Bartonella species.Citation43 Iridocyclitis due to Bartonella infection may be granulomatous or nongranulomatous as well and recurrent iridocyclitis has been also reported.Citation72

Bartonella species are fastidious bacteria, difficult to grow and requiring long incubation periods in enriched media for 2 to 6 weeks. Often isolation in culture is unsuccessful. The diagnosis of Bartonella infection is commonly made using serologic testing with immunofluorescence antibody analysis (IFA) or enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA).Citation66,Citation73 The sensitivities and specificities of these methods vary in different reports and different cutoff values are used. The chosen cutoff value in the serological examination (IFA) in the patients of our study reflects our effort to avoid underdiagnosis. If serology is negative, a second sample after 2 months may show a seroconversion. Cross-reactions have been reported between Bartonella species and with Coxiella burnetti and Chlamydia pneumoniae. Western blot analysis and cross-adsorption can solve this problem and increase the specificity of the test.Citation34 Also polymerase chain reaction (PCR) analysis of tissue samples can be used for diagnosis.Citation74 Intraocular fluid analysis using PCR can confirm the diagnosis of Bartonella intraocular inflammation as well.Citation43

In immunocompetent patients the ocular manifestations of Bartonella infection tend to be self-limited and have a benign course. However, some patients may have more severe ocular complications, especially those with intraocular inflammation. Early antibiotic treatment seems to shorten the course of infection and hasten visual recoveryCitation52 and this was also the basis of the management of our patients with Bartonella uveitis. In immunocompromised patients,the ocular manifestations tend to be more severe and an early intensive antibiotic treatment is required. A variety of antibiotics have been reported to have good efficacy including rifampicin, doxycycline, azithromycin, ciprofloxacin, trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole and gentamycin. The antibiotic treatment lasts 2–4 weeks for immunocompetent patients and up to 4 months for immunocompromised patients.Citation16 In our patients, all immunocompetent, a 4-week treatment protocol was performed to eradicate the infectious agent.

Pet owners should be informed about the risks that exist from the infestation of the pets with fleas or ticks and control measures should be taken to avoid such infestation. Also homeless people, drug addicts and alcoholics should be informed of the risks that exist from the presence of human body lice and control measures should be taken as well. In addition, these individuals, because of the poor living conditions and lack of hygiene, may also be exposed to rodent-borne Bartonella species. Finally, immunocompromised patients should be especially careful, because Bartonella infection can be severe or even fatal for them, and prevention is the best solution.

Intraocular involvement caused not only by B. henselae but also by B. quintana is being diagnosed with increasing frequency. The combination of POGS and intraocular inflammation in the same patient seems to be very rare and this is also observed in our own cases.Citation50 Although the possibility of B. henselae infection should be considered in patients with neuroretinitis, other forms of uveitis and retinal vasculitis may be present even in the absence of systemic symptoms of cat scratch disease, especially in cases of B. quintana infection, which is underestimated as a cause of intraocular inflammation. Serological data must be interpreted especially along with a positive history of exposure to cat-scratching or biting, and the clinical picture; a high index of suspicion should be retained, because some associations may remain underdescribed.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- ChomelBBBoulouisHJBreitschwerdtEBEcological fitness and strategies of adaptation of Bartonella species to their hosts and vectorsVet Res20094022919284965

- ChomelBBAbbottRCKastenRWBartonella henselae prevalence in domestic cats in California: risk factors and association between bacteremia and antibody titersJ Clin Microbiol1995339244525507494043

- ChomelBBBoulouisHJPetersenHPrevalence of Bartonella infection in domestic cats in DenmarkVet Res200233220521311944808

- BirtlesRJLaycockGKennyMJShawSEDayMJPrevalence of Bartonella species causing bacteraemia in domesticated and companion animals in the United KingdomVet Rec2002151822522912219899

- BarnesABellSCIsherwoodDRBennettMCarterSDEvidence of Bartonella henselae infection in cats and dogs in the United KingdomVet Rec20001472467367711132671

- FabbiMVicariNTranquilloMPrevalence of Bartonella henselae in stray and domestic cats in different Italian areas: evaluation of the potential risk of transmission of Bartonella to humansParassitologia2004461–212712915305701

- MaruyamaSNakamuraYKabeyaHTanakaSSakaiTKatsubeYPrevalence of Bartonella henselae, Bartonella clarridgeiae and the 16S rRNA gene types of Bartonella henselae among pet cats in JapanJ Vet Med Sci200062327327910770599

- GuptillLWuCCHogenEschHPrevalence, risk factors, and genetic diversity of Bartonella henselae infections in pet cats in four regions of the United StatesJ Clin Microbiol200442265265914766832

- KellyPJMatthewmanLAHayterDBartonella (Rochalimaea) henselae in southern Africa – evidence for infections in domestic cats and implications for veterinariansJ S Afr Vet Assoc19966741821879284029

- ChomelBBKastenRWFloyd-HawkinsKExperimental transmission of Bartonella henselae by the cat fleaJ Clin Microbiol1996348195219568818889

- LamasCCuriABóiaMLemosEHuman bartonellosis: seroepidemiological and clinical features with an emphasis on data from Brazil – a reviewMem Inst Oswaldo Cruz2008103322123518592096

- BassJWVincentJMPersonDAThe expanding spectrum of Bartonella infections: II. Cat-scratch diseasePediatr Infect Dis J19971621631799041596

- CarithersHACat-scratch disease. An overview based on a study of 1,200 patientsAm J Dis Child198513911112411334061408

- JacobsRFSchutzeGEBartonella henselae as a cause of prolonged fever and fever of unknown origin in childrenClin Infect Dis199826180849455513

- CunninghamETKoehlerJEOcular bartonellosisAm J Ophthalmol2000130334034911020414

- RoeRHMichael JumperJFuADJohnsonRNRichard McDonaldHCunninghamETOcular bartonella infectionsInt Ophthalmol Clin20084839310518645403

- DunnMWBerkowitzFEMillerJJSnitzerJAHepatosplenic cat-scratch disease and abdominal painPediatr Infect Dis J19971632692729076813

- FournierPELelievreHEykynSJEpidemiologic and clinical characteristics of Bartonella quintana and Bartonella henselae endocarditis: a study of 48 patientsMedicine (Baltimore)200180424525111470985

- BrouquiPRaoultDEndocarditis due to rare and fastidious bacteriaClin Microbiol Rev200114117720711148009

- MarraCMNeurologic complications of Bartonella henselae infectionCurr Opin Neurol1995831641697551113

- OguraKHaraYTsukaharaHMaedaMTsukaharaMMayumiMMR signal changes in a child with cat scratch disease encephalopathy and status epilepticusEur Neurol200451210911014963382

- GerberJEJohnsonJEScottMAMadhusudhanKTFatal meningitis and encephalitis due to Bartonella henselae bacteriaJ Forensic Sci200247364064412051353

- van ToorenRMvan LeusenRBoschFHCulture negative endocarditis combined with glomerulonephritis caused by Bartonella species in two immunocompetent adultsNeth J Med200159521822411705641

- VermeulenMJRuttenGJVerhagenIPeetersMFvan DijkenPJTransient paresis associated with cat-scratch disease: case report and literature review of vertebral osteomyelitis caused by Bartonella henselaePediatr Infect Dis J200625121177118117133166

- TsukaharaMTsuneokaHTateishiHFujitaKUchidaMBartonella infection associated with systemic juvenile rheumatoid arthritisClin Infect Dis2001321E22E2311112671

- WongTZKruskalJKaneRATreyGCat-scratch disease simulating lymphomaJ Comput Assist Tomogr19962011651668576472

- MarkakiSSotiropoulouMPapaspirouPLazarisDCat-scratch disease presenting as a solitary tumour in the breast: report of three casesEur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol2003106217517812551788

- MillotFTailbouxLPaccalinMCat-scratch disease simulating a malignant process of the chest wallEur J Pediatr1999158540340510333124

- MarrBPShieldsCLShieldsJAEagleRCJrConjunctival cat-scratch disease simulating rhabdomyosarcomaJ Pediatr Ophthalmol Strabismus200340530230314560840

- KempfVAPetzoldHAutenriethIBCat scratch disease due to Bartonella henselae infection mimicking parotid malignancyEur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis2001201073273311757975

- ChomelBBCat-scratch disease and bacillary angiomatosisRev Sci Tech1996153106110739025151

- KoehlerJEBartonella-associated infections in HIV-infected patientsAIDS Clin Care19957129710211362939

- NadalDZbindenRIllnesses caused by Bartonella. Cat-scratch disease, bacillary angiomatosis, bacillary peliosis hepatis, endocarditisInternist (Berl)19963798908948964682

- FoucaultCBrouquiPRaoultDBartonella quintana characteristics and clinical managementEmerg Infect Dis200612221722316494745

- BonillaDLKabeyaHHennJKramerVLKosoyMYBartonella quintana in body lice and head lice from homeless persons, San Francisco, California, USAEmerg Infect Dis200915691291519523290

- BrouquiPHoupikianPDupontHTSurvey of the seroprevalence of Bartonella quintana in homeless peopleClin Infect Dis19962347567598909840

- SekiNSasakiTSawabeKEpidemiological studies on Bartonella quintana infections among homeless people in Tokyo, JapanJpn J Infect Dis2006591313516495631

- ComerJAFlynnCRegneryRLVlahovDChildsJEAntibodies to Bartonella species in inner-city intravenous drug users in Baltimore, MdArch Intern Med199615621249124958944742

- BreitschwerdtEBMaggiRGSigmonBNicholsonWLIsolation of Bartonella quintana from a woman and a cat following putative bite transmissionJ Clin Microbiol200745127027217093037

- LaVDTran-HungLAboudharamGRaoultDDrancourtMBartonella quintana in domestic catEmerg Infect Dis20051181287128916102321

- O’RourkeLGPitulleCHegartyBCBartonella quintana in cynomolgus monkey (Macaca fascicularis)Emerg Infect Dis200511121931193416485482

- KaremKLPaddockCDRegneryRLBartonella henselae, B. quintana, and B. bacilliformis: historical pathogens of emerging significanceMicrobes Infect20002101193120511008109

- TerradaCBodaghiBConrathJRaoultDDrancourtMUveitis: an emerging clinical form of Bartonella infectionClin Microbiol Infect200915Suppl 213213319548998

- ParinaudHConjunctivite infectieuse transmise par les animauxAnn d’Oculistique1889101252253

- BorboliSAfshariNAWatkinsLFosterCSPresumed oculoglandular syndrome from Bartonella quintanaOcul Immunol Inflamm2007151414317365807

- OrmerodLDDaileyJPOcular manifestations of cat-scratch diseaseCurr Opin Ophthalmol199910320921610537781

- SuhlerEBLauerAKRosenbaumJTPrevalence of serologic evidence of cat scratch disease in patients with neuroretinitisOphthalmology2000107587187610811077

- EggenbergerECat scratch disease: posterior segment manifestationsOphthalmology2000107581781810811065

- WadeNKPoSWongIGCunninghamETJrBilateral Bartonella-associated neuroretinitisRetina199919435535610458308

- WongMTDolanMJLattuadaCPJrNeuroretinitis, aseptic meningitis, and lymphadenitis associated with Bartonella (Rochalimaea) henselae infection in immunocompetent patients and patients infected with human immunodeficiency virus type 1Clin Infect Dis19952123523608562744

- WadeNKLeviLJonesMRBhisitkulRFineLCunninghamETJrOptic disk edema associated with peripapillary serous retinal detachment: an early sign of systemic Bartonella henselae infectionAm J Ophthalmol2000130332733411020412

- ReedJBScalesDKWongMTLattuadaCPJrDolanMJSchwabIRBartonella henselae neuroretinitis in cat scratch disease. Diagnosis, management, and sequelaeOphthalmology199810534594669499776

- GeorgeJGBradleyJCKimbroughRC3rdShamiMJBartonella quintana associated neuroretinitisScand J Infect Dis200638212712816449005

- KerkhoffFTBergmansAMvan Der ZeeARothovaADemonstration of Bartonella grahamii DNA in ocular fluids of a patient with neuroretinitisJ Clin Microbiol199937124034403810565926

- O’HalloranHSDraudKMinixMRivardAKPearsonPALeber’s Neuroretinitis in a patient with serologic evidence of Bartonella elizabethaeRetina19981832762789654422

- CuriALMachadoDHeringerGCat-scratch disease: ocular manifestations and visual outcomeInt Ophthalmol201030555355820668914

- OrmerodLDSkolnickKAMenoskyMMPavanPRPonDMRetinal and choroidal manifestations of cat-scratch diseaseOphthalmology19981056102410319627652

- KhuranaRNAlbiniTGreenRLRaoNALimJIBartonella henselae infection presenting as a unilateral panuveitis simulating Vogt-Koyanagi-Harada syndromeAm J Ophthalmol200413861063106515629311

- DonnioAJean-CharlesAMerleHMacular hole following Bartonella henselae neuroretinitisEur J Ophthalmol200818345645818465733

- GrayAVMichelsKSLauerAKSamplesJRBartonella henselae infection associated with neuroretinitis, central retinal artery and vein occlusion, neovascular glaucoma, and severe vision lossAm J Ophthalmol2004137118718914700670

- KawasakiAWilsonDLMass lesions of the posterior segment associated with Bartonella henselaeBr J Ophthalmol200387224824912543767

- GrayAVReedJBWendelRTMorseLSBartonella henselae infection associated with peripapillary angioma, branch retinal artery occlusion, and severe vision lossAm J Ophthalmol1999127222322410030575

- SerratriceJRolainJMGranelBBilateral retinal artery branch occlusions revealing Bartonella grahamii infectionRev Med Interne2003249629630 French.12951187

- CuriALMachadoDOHeringerGCamposWROreficeFOcular manifestation of cat-scratch disease in HIV-positive patientsAm J Ophthalmol2006141240040116458711

- SoheilianMMarkomichelakisNFosterCSIntermediate uveitis and retinal vasculitis as manifestations of cat scratch diseaseAm J Ophthalmol199612245825848862061

- AmereinMPDe BrielDJaulhacBMeyerPMonteilHPiemontYDiagnostic value of the indirect immunofluorescence assay in cat scratch disease with Bartonella henselae and Afipia felis antigensClin Diagn Lab Immunol1996322002048991636

- MandevilleJLevinsonRHollandGThe tubulointerstitial nephritis and uveitis syndromeSurv Ophthalmol200146319520811738428

- PipiliCKatsogridakisKCholongitasEMyocarditis due to Bartonella henselaeSouth Med J200810111118619088543

- JabsDANussenblattRBRosenbaumJTStandardization of Uveitis Nomenclature (SUN) Working GroupStandardization of uveitis nomenclature for reporting clinical data. Results of the First International WorkshopAm J Ophthalmol2005140350951616196117

- SolleyWAMartinDFNewmanNJCat scratch disease: posterior segment manifestationsOphthalmology199910681546155310442903

- MeiningerGRNadasdyTHrubanRHBollingerRCBaughmanKLHareJMChronic active myocarditis following acute Bartonella henselae infection (cat scratch disease)Am J Surg Pathol20012591211121411688584

- Martínez-OsorioHCalongeMTorresJGonzálezFCat-scratch disease (ocular bartonellosis) presenting as bilateral recurrent iridocyclitisClin Infect Dis2005405e43e4515714406

- RegneryRLOlsonJGPerkinsBABibbWSerological response to “Rochalimaea henselae” antigen in suspected cat-scratch diseaseLancet19923398807144314451351130

- HansmannYDeMartinoSPiémontYMeyerNMarietPHellerRDiagnosis of cat scratch disease with detection of Bartonella henselae by PCR: a study of patients with lymph node enlargementJ Clin Microbiol20054383800380616081914