Abstract

Posterior scleritis is a rare underdiagnosed condition that can potentially cause blindness. Its varied presentations lead to delayed or incorrect treatment. We present here the cases of two patients with nodular posterior scleritis mimicking a choroidal metastasis. Two female patients presented with a sudden unilateral visual loss associated with ocular pain. Fundus examination revealed temporomacular choroidal masses with exudative detachments that, due to angiographic presentation, were suggestive of choroidal metastasis. Systemic examinations were unremarkable. In the two cases, a local or general anti-inflammatory treatment led to the complete recovery of the lesions, which were, thus, considered nodular posterior scleritis. The diagnosis of nodular posterior scleritis has to be evoked in all patients presenting with a choroidal mass in fundus examination. It represents the principal curable differential diagnosis of malignant choroidal tumor.

Introduction

Posterior scleritis is often misdiagnosed due to its low incidence. This inflammatory condition of the eye wall can concern the whole sclera in its diffuse form or involve only a part of it in its nodular presentation. Nodular posterior scleritis (NPS) can simulate a choroidal tumor. A few cases have been reported showing the difficulty in differentiating these two conditions and to introduce an appropriate treatment. We report here the cases of two female patients who were initially diagnosed with a choroidal metastasis and who healed with an anti-inflammatory treatment.

Case presentation

Case 1

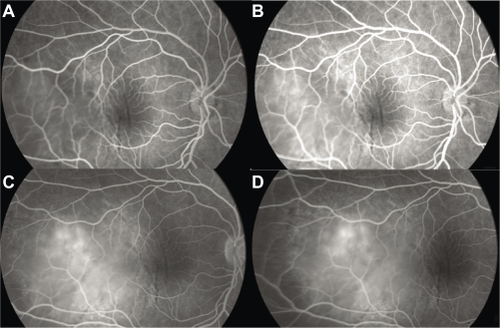

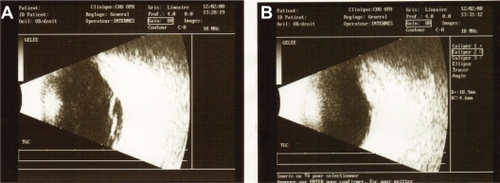

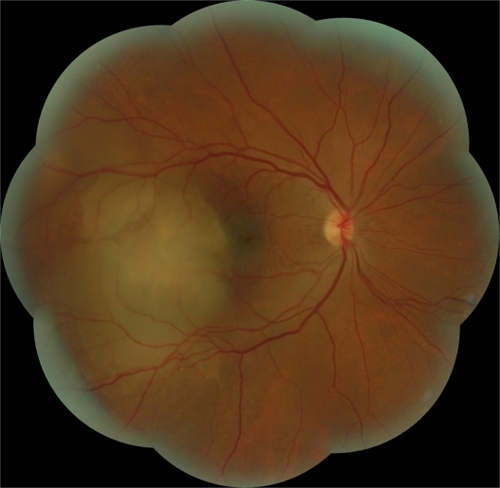

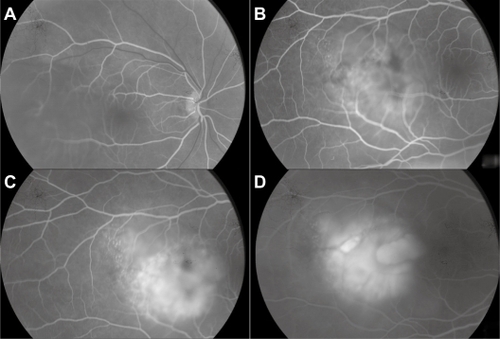

A 38-year-old Afro-Caribbean woman was referred to our center with sudden visual loss associated with ocular pain. She had no significant medical history. Local treatment had already been introduced. It consisted of corticosteroid drops associated with mydriatics. The patient felt a slight improvement, but the pain recurred and the acuity decreased considerably. Best-corrected visual acuity was 20/80 in the right eye and 20/20 in the left eye. There was no ocular redness. Anterior segment was unremarkable. Funduscopic examination of the right eye revealed a single yellowish choroidal mass temporal to the macula associated with an exudative detachment in the inferior retina (). Fluorescein angiography (FA) exhibited an early heterogenous hyperfluorescence (). B-scan ultrasonography showed a dome-shaped mass with fluid in the subretinal space (). With the exception of the mass that was prominent in the vitreous cavity, measuring 11 mm × 4.6 mm, sclera had a normal aspect. There was no orbital shadowing. Blood tests highlighted an isolated inflammatory syndrome with an accelerated sedimentation rate (98 mm the first hour) but complete blood cell count, rheumatoid factor, angiotensin converting enzyme, and antinuclear antibodies were normal. Oncologic examination showed no evidence for a systemic malignancy. The patient underwent brain magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), body-scan, mammography, thyroid ultrasonography, gastroscopy, and positron emission tomography scan. Based on the clinical and radiological evaluations, the diagnosis of NPS was made. Oral corticotherapy was initiated, and the patient was monitored 3 weeks later. Visual acuity in the right eye improved to 20/40 and the fundus examination no longer showed abnormalities. The patient stopped her treatment 4 weeks later. Visual acuity then continued to improve to 20/20. She did not experience any recurrence of the symptoms in the subsequent 2 years.

Figure 1 Case 1. Fundus photograph. Massive yellowish lesion, temporal to fovea, with an exudative detachment involving the fovea and choroidal folds.

Case 2

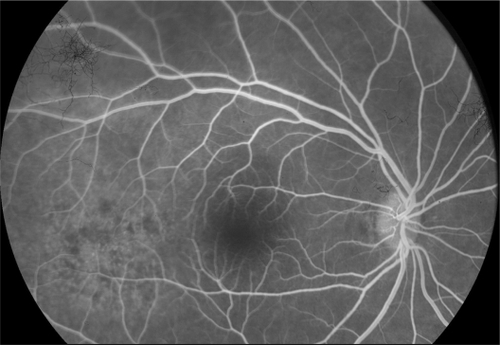

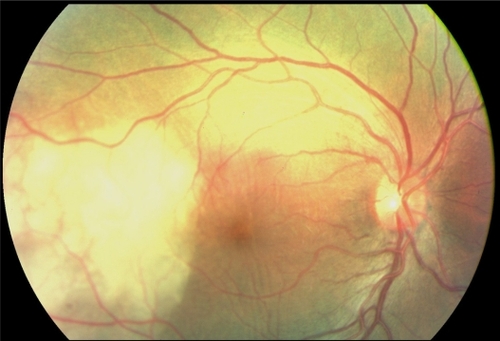

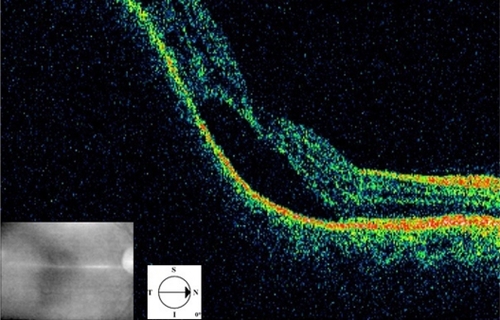

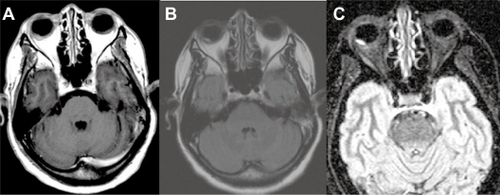

A 52-year-old woman presented with sudden visual loss in the right eye. She experienced ocular pain and unusual headache for 1 month before the visual impairment. She had no significant medical history, but one of her sisters had died of breast cancer. Her visual acuity was 20/200 in the right eye and 20/20 in the left eye. There were no abnormalities in her anterior segments. Right fundus examination exhibited a unique and massive yellowish lesion temporal to fovea with an exudative detachment involving the fovea and extending inferiorly (). There were no vitreous cells. FA highlighted a progressive and heterogeneous hyperfluorescence during the sequence and pin points. There was no dual circulation (). Optical coherence tomography examination highlighted serous subretinal fluid surrounding an elevation of the retina (). The patient was treated with nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory eye drops and underwent a general and oncologic evaluation. Brain MRI showed a high-signal dome-shaped lesion on fluid-attenuated inversion recovery sequences (). Two weeks later, while the radiological evaluation was initiated, she reported an improvement in visual acuity. Fundus examination was surprisingly normal. Neither retinal lesion nor serous detachment was observed. FA showed a punctuated hyperfluorescence in place of the initial lesion, suggesting retinal pigment epithelium atrophy (). No general inflammatory disease was found. The patient did not experience any other recurrence in the subsequent 5 months.

Figure 4 Case 2. Fundus photograph. Unique and massive orange-yellow protruding lesion temporal to macula with an exudative detachment involving the fovea and extending inferiorly.

Figure 5 Case 2. Fluorescein angiography sequence. Progressive and heterogeneous hyperfluorescence, with pin points temporal to the mass.

Figure 6 Case 2. Optical coherence tomography. Serous retinal detachment and elevation of the retina depending on a choroidal mass.

Figure 7 Case 2. Brain magnetic resonance imaging in FLAIR (fluid-attenuated inversion recovery sequence) (A), T1 weighted with gadolinium (B) and STIR (short-tau inversion recovery sequence) (C). The nodular lesion appears in well limited hypersignal in the right eye, with no gadolinium enhancement. The hypersignal is most prominent in the STIR sequence.

Discussion

Diffuse and nodular posterior scleritis share the same etiologies than anterior orbital inflammations (the most common is Wegener’s granulomatosis) when they are not idiopathic.Citation1 No inflammatory etiology was found in our two patients, despite the isolated biological inflammatory syndrome of the first one which cleared up spontaneously.

Clinically, pain is the symptom that leads to considering a possible inflammatory disease. Indeed, choroidal tumors are indolent as a rule. Hatef et al ascribes this functional sign to the relatively frequent association of anterior segment involvement.Citation2 However, our patients reported ocular pain but did not show any ocular redness.

At fundus examination, the nodular inflammatory lesion cannot be distinguished from a choroidal metastasis or an achromic melanoma; so much so that some patients have undergone enucleation.Citation3 Nevertheless, some clinical signs can help with the diagnosis. The association with anterior scleritis, a serous retinal detachment and, more seldom, a papillary edema are suggestive of an inflammatory condition.

The key for diagnosis is probably the B-scan ultrasonography. In NPS, there is a thickening of the sclera and a diffuse hyperechogenicity of the mass without orbital shadowing, unlike melanoma or metastasis, which are both characterized by a moderate hyperechogenicity or a hypoechogenicity. Presence of fluid next to the dome-shaped mass explains the low visual acuity in our first patient () and is furthermore an argument for the inflammatory etiology. In both tumors and NPS, FA reveals pin points in the lesion area, but the presence of a dual circulation is a strong argument for a choroidal melanoma. If a biopsy is undergone, the sclera can appear thickened and infiltrated with inflammatory cells. Granulomatous reaction and areas of necrosis can also be observed.Citation3

Corticotherapy led to a total recovery of the symptoms in our first patient, while the lesion of the second disappeared with nonsteroid anti-inflammatory drops. Previous reports of NPS show a favorable evolution in most cases, but the aggressiveness of the treatments used is very heterogeneous. Indeed, Demirci reports a 12-year follow-up of giant NPS stabilizing without treatment.Citation4 Other authors report the use of high-dose intravenous corticotherapy, which can be associated with immunosuppressive drugs.Citation2,Citation5

In a large series of posterior scleritis, McCluskey et alCitation1 used systemic corticosteroids and immunosuppressive therapy when patients presented visual loss, optic nerve involvement, or associated systemic diseasess. Idiopathic scleritis would favorably respond to a local nonsteroid anti-inflammatory treatment as in the case of our second patient.

Conclusion

The scarcity of NPS does not allow a specific care protocol to be established. Decreased visual acuity justifies a general anti-inflammatory treatment, which may be considered as a therapeutic test. It is thus suitable to evoke this diagnosis in all cases of choroidal tumor, especially when the patient is a female with no evidence for a general neoplastic disease.

Consent

Written consent for publication was obtained from the patients.

Authors’ contributions

AJC, JG, and RH treated the patients and in doing so acquired the case data. RH, AJC, and HM were involved with drafting of the manuscript. AD and OR assisted in data acquisition and were involved with drafting the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- McCluskeyPJWatsonPGLightmanSHaybittleJRestoriMBranleyMPosterior scleritis: clinical features, systemic associations, and outcome in a large series of patientsOphthalmology19991062380238610599675

- HatefEWangJIbrahimMNodular sclerochoroidopathy simulating choroidal malignancyOphthalmic Surg Lasers Imaging20103041 Online: e1–e5.

- FingerPTPerryHDPackerSErdeyRAWeismanGDSibonyPAPosterior scleritis as an intraocular tumourBr J Ophthalmol1990741211222178679

- DemirciHShieldsCLHonavarSGShieldsJABardensteinDSLong-term follow-up of giant nodular posterior scleritis simulating choroidal melanomaArch Ophthalmol20001181290129210980778

- ShuklaDKimRGiant nodular posterior scleritis simulating choroidal melanomaIndian J Ophthalmol20065412012216770031