Abstract

Purpose

To report the use of corneal collagen crosslinking in the treatment of infective keratitis not responding to antimicrobial therapy.

Methods

Two retrospective case reports of infective keratitis treated with corneal collagen crosslinking.

Results

In both cases, corneal collagen crosslinking caused a rapid resolution of the infective keratitis, leaving residual stromal scarring. Due to the density of scarring, one case required subsequent penetrating keratoplasty for visual rehabilitation.

Conclusion

Corneal collagen crosslinking is a promising new technique for the management of infective keratitis not responding to antimicrobial therapy. Further elucidation of its safety and role in management of infectious keratitis is needed by way of future studies.

Keywords:

Introduction

Ulcerative keratitis is a sight-threatening condition, which requires skilled management and effective chemotherapy to preserve vision. If appropriate antimicrobial treatment is delayed, it is estimated that only 50% of eyes heal with good visual outcome.Citation1

The treatment of corneal ulcers with topical antimicrobial agents has been confounded by the ability of microbes to develop resistance to the drugs used. There is therefore a need for an agent which provides complete, rapid antimicrobial activity with a minimum of toxicity.

Riboflavin and ultraviolet light (UV) collagen crosslinking of the cornea induces a change in properties of the collagen and has a stiffening effect on the corneal stroma, which stabilizes it and increases its resistance to enzymatic degradation.Citation2,Citation3

Although corneal collagen crosslinking was originally introduced as a treatment for corneal ectasia by Wollensak et alCitation4,Citation5 it has been used in the treatment of a variety of other conditions such as symptomatic Fuch’s corneal dystrophy,Citation6 pseudophakic bullous keratopathy,Citation7 and more recently, infectious keratitis.Citation8–Citation11

These two case reports describe the authors’ experience with corneal collagen crosslinking for the treatment of infectious keratitis.

Case 1

A 30-year-old lady presented at Magrabi Eye Hospital as a referral from a local ophthalmologist with a 2-week history of pain, redness, and decreased vision in her right eye. The referring ophthalmologist had diagnosed her as having bacterial keratitis in her right eye. Culture and sensitivity results showed Staphylococcus aureus to be the causative microorganism. Treatment had already been initiated with intensive topical fortified antibiotic therapy with hourly fortified cefuroxime drops (5%) together with hourly fortified gentamicin drops (1.5%). However, in spite of initial sensitivities showing susceptibility to these antibiotics, the infection had progressed.

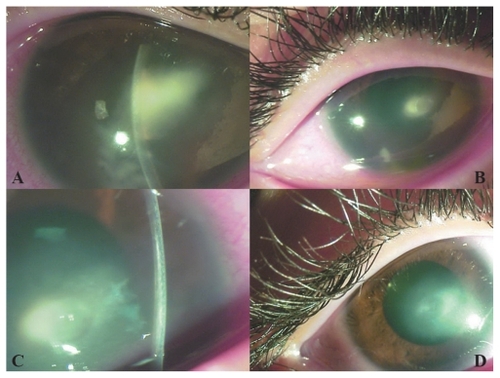

Best-corrected visual acuities (BCVAs) were finger counting at 1 meter in the right eye and 20/20 in the left eye. Ocular examination showed an elliptical, central area of corneal infiltration, 4 mm × 2 mm in diameter (). A moderate anterior chamber reaction of more than two cells was seen, and no hypopyon. The conjunctiva was congested, but no purulent discharge was seen.

Figure 1 Appearance of case 1 (A) at initial presentation, (B) 2 weeks after crosslinking, (C) 2 weeks after crosslinking (note the stromal demarcation line due to crosslinking, adjacent to the abscess), and (D) 2 months after crosslinking.

Medications were stopped for 24 hours, after which corneal scraping was repeated to obtain material for Gram and Giemsa slides, together with culture and sensitivity plating. The fortified gentamicin 1.5% and cefuroxime 5% drops were recommenced. However, gram stain and cultures yielded no result.

A week later, the corneal abscess appeared to have increased in size. The risks of progression and corneal perforation, if treatment continued with conservative management, were weighed against the possible benefits of decreasing the load of pathogen with UV irradiation were discussed with the patient, after which the decision was made to proceed with UVA-riboflavin collagen crosslinking.

Topical anesthesia was achieved using 0.4% benoxinate drops. Epithelium was not removed as there was already a large epithelial defect overlying the abscess. Riboflavin drops (Medio-Cross® riboflavin/dextran solution, 0.1%) were instilled topically to the cornea for a period of 20–30 minutes at an interval of 2–3 minutes. The cornea was then illuminated using a UVX lamp (PeschkeMeditrade GmbH, Huenenberg, Switzerland), UVA 365 nm, with an irradiance of 3 mW/cm2 and a total dose of 5.4 J/cm2.

During the period of UV illumination, riboflavin was administered to the right eye at the same interval. Following this, treatment with gentamicin 1.5% and cefuroxime 5% drops was recommenced. Topical corticosteroids were not prescribed after the crosslinking procedure.

Follow-up examination at 1 week showed that the abscess had reduced in size to 2 mm in diameter and its margins were better defined. The epithelial defect overlying the abscess was also smaller. The patient also stated that she felt less pain. The medication was tapered at this point bringing the frequency of antibiotic drop instillation down to every 2 hours during the day.

Two weeks after crosslinking, the corneal abscess and epithelium had completely healed, with a residual scar remaining (). A demarcation line was clearly visible in the cornea adjacent to the corneal abscess (). BCVA improved to 20/100. Fortified antibiotic drops were discontinued and replaced by fluorometholone 0.1%/gentamicin 0.3% (Infectoflam, Novartis Pharma AG, Basel, Switzerland) drops twice daily for 1 month. At 2 months, the BCVA was 20/40, the infection had completely resolved, but vision was impaired by a central corneal scar ().

Case 2

A 47-year-old laborer was referred to Magrabi Eye Hospital from another city after having been unsuccessfully treated for fungal keratitis at another hospital. He gave a vague history of some debris entering his eye while working a month back. After corneal scraping for Gram staining, Giemsa staining, and culture plating, he had initially been placed on hourly ciprofloxacin 0.3% eye drops. These had been changed to amphotericin 2 mg/mL eye drops after Sabouraud agar grew Aspergillus as a causative organism.

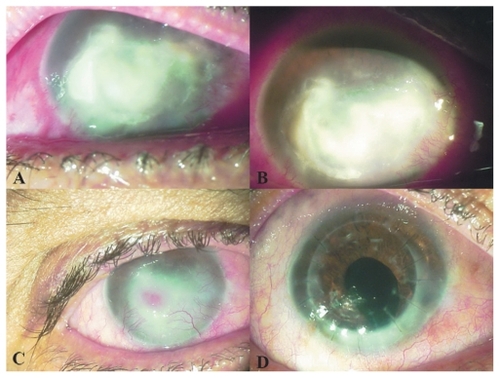

Visual acuities were hand motion in the right eye with accurate light projection and 20/20 in the left eye. Ocular examination showed a large corneal abscess measuring 9 mm horizontally by 7 mm vertically (). Temporally, the abscess was approaching the limbus. The bulbar and forniceal conjunctiva showed some patches of necrosis from prolonged amphotericin B treatment. Initial corneal scrapings yielded no hyphae, but a subsequent corneal biopsy confirmed the diagnosis of Aspergillus spp.

Figure 2 Appearance of case 2 (A) at initial presentation, (B) 1 week after crosslinking (note the cleaner margins and decreased infiltrate density of the abscess), (C) 2 months after crosslinking (infiltration has been replaced by scar tissue; note the presence of an intrastromal hemorrhage), and (D) after penetrating keratoplasty combined with cataract extraction.

Considering the large size of the abscess and its proximity to the limbus, a therapeutic penetrating keratoplasty (PKP) was felt to be the most appropriate management. However, given the poor outcomes of corneal grafting procedures in infectious keratitis, UVA-riboflavin crosslinking was performed in an attempt to decrease the fungal load in the corneal abscess. Treatment with hourly amphotericin 2 mg/mL eye drops was continued after the procedure. No topical corticosteroids were prescribed. One week after crosslinking, the corneal abscess appeared to have better-defined margins and less infiltration than before (). The epithelial defect appeared slightly smaller. Amphotericin drops were gradually tapered over the coming weeks.

Two months after crosslinking, the abscess had been replaced by scar tissue. The lesion diameter had decreased to 3 mm. Superficial and deep stromal blood vessels were encroaching on the central cornea, causing an intra-abscess bleed (). By this point, the corneal epithelium had healed over the abscess. Amphotericin drops were discontinued.

Four months after crosslinking, penetrating keratoplasty combined with extracapsular cataract extraction and intraocular lens implantation was performed, uneventfully (). BCVA 6 months after the graft was 20/50, with a manifest refraction of –2–4 × 85.

Discussion

The case reports presented here show that corneal collagen crosslinking has two possible roles in the treatment of infectious keratitis not responding to antibiotic therapy.

Firstly, the antimicrobial properties of UVA radiation destroy pathogenic microorganisms in the cornea, aiding resolution of the keratitis. Secondly, the crosslinking helps avoid an emergency penetrating keratoplasty with its associated high risks of graft rejection. The reported rates of graft rejection after therapeutic PKP range from 14.6% to 52% in various reported series.Citation12–Citation14 A 26% graft failure rate after rejection in therapeutic PKPs was reported by Hill.Citation15

Tsugita et alCitation16 showed that exposing riboflavin to UV light caused a deactivation of the ribonucleic acid (RNA) tobacco mosaic virus. Since then, research has been done to look into the possibility of using riboflavin as a photosensitizer to deactivate pathogens in plasma, platelet, and red cell products.Citation17–Citation19 The efficacy of UV light is limited only by its lack of penetration and its dependence on the distance from the light source. The cornea itself contains riboflavin already, but the concentration present is not enough to have antimicrobial effects in keratitis. The small amount of corneal riboflavin present may become depleted on exposure to sunlight.Citation20

Martins et al showed that a combination of UVA-riboflavin has antibacterial properties in vitro against micro-organisms such as Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Staphylococcus aureus, Staphylococcus epidermidis, methicillin resistant Staphyloccus aureus, drug-resistant Streptococcus pneumoniae, and multidrug-resistant Pseudomonas aeruginosa.Citation21 Pathogen inactivation occurs via the byproducts of riboflavin after UVA exposure. Nucleic acids are damaged by direct electron transfer, production of singlet oxygen, and generation of hydrogen peroxide with the formation of hydroxyl radicals. Pathogen deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA)/RNA may even be affected in the absence of oxygen.Citation22,Citation23

Spoerl et alCitation24 showed that porcine corneas which underwent crosslinking were more resistant to the effects of pepsin, collagenase, and trypsin. Pepsin digested crosslinked eyes in 13 days and untreated eyes in 6 days. Collagenase digested treated corneas in 14 days and untreated eyes in 6 days. Trypsin digested treated corneas in 5 days and untreated corneas in 2 days. It is quite possible that part of the therapeutic effect of crosslinking in these cases was due to the decreased susceptibility of the corneal stroma to proteolytic enzymes produced by pathogenic bacteria.

The bactericidal and stromal strengthening properties of crosslinking make it a very attractive option for treating bacterial keratitis, as has been shown in case series by other authors. Al-Sabai describes a case of keratitis due to Pseudomonas spp. in which crosslinking helped induce corneal cicatrization.Citation8 Iseli et al successfully crosslinked five patients with corneal melting due to infectious keratitis. Melting was arrested in all cases, with none requiring emergency keratoplasty.Citation9 Makdoumi et al treated seven eyes of six patients with severe infectious keratitis, with crosslinking causing an arrest of melting and complete epithelialization in all cases, with a resolution of symptoms within 24 hours.Citation10 Schnitzler reported that the treatment resulted in complete healing in two cases and delayed the need for surgery in another two cases.Citation11 The findings of those case reports are mirrored in this current report, although the speed of resolution of these current cases was not as rapid as reported by Makdoumi et al.

In the bacterial infection, while fortified topical antibiotic therapy alone did not have the desired effect on the corneal abscess, the crosslinking led to a resolution of infection with an acceptable visual outcome, considering the location of the abscess.

The initial presentation of the fungal infection was clearly far more severe than that of the case of bacterial keratitis. The severity of the infection and the central location of the abscess caused scarring which limited the final visual acuity achieved. Penetrating keratoplasty was eventually required, but this was a more planned procedure in a less inflamed eye as compared with the therapeutic PKP which might have been performed in an acute setting.

In conclusion, UVA-riboflavin crosslinking could prove to be a valuable addition to our armamentarium for the treatment of keratitis not responding to antimicrobial therapy. In addition, it allows us to delay therapeutic PKP procedures to a later date when they can be performed in a more controlled manner with a possibly lower risk of subsequent graft failure. However, until more data is available crosslinking should only be considered in keratitis resistant to treatment.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work. This subject material has not been published elsewhere previously.

References

- JonesDBDecision-making in the management of microbial keratitisOphthalmol1981888814820

- WollensakGSpoerlESeilerTStress-strain measurements of human and porcine corneas after riboflavin-ultraviolet-A-induced crosslinkingJ Cataract Refract Surg2003291780178514522301

- SpoerlEWollensakGSeilerTIncreased resistance of crosslinked cornea against enzymatic digestionCurr Eye Res200429354015370365

- WollensakGSpoerlESeilerTRiboflavin/ultraviolet-A-induced collagen crosslinking for the treatment of keratoconusAm J Ophthalmol2003135562062712719068

- WollensakGSporlESeilerTTreatment of keratoconus by collagen crosslinking (in German)Ophthalmologe20031001444912557025

- HafeziFDejicaPMajoFModified corneal collagen crosslinking reduces corneal oedema and diurnal visual fluctuations in Fuchs dystrophyBr J Ophthalmol201094566066120447971

- GhanemRCSanthiagoMRBertiTBThomazSNettoMVCollagen crosslinking with riboflavin and ultraviolet-A in eyes with pseudophakic bullous keratopathyJ Cataract Refract Surg201036227327620152609

- Al-SabaiNKoppenCTassignonMJUVA/riboflavin crosslinking as treatment for corneal meltingBull Soc Belge Ophtalmol2010315131721110504

- IseliHPThielMAHafeziFUltraviolet A/riboflavin corneal cross-linking for infectious keratitis associated with corneal meltsCornea200827559059418520510

- MakdoumiKMortensenJCrafoordSInfectious keratitis treated with corneal crosslinkingCornea201029121353135821102196

- SchnitzlerESpörlESeilerTIrradiation of cornea with ultraviolet light and riboflavin administration as a new treatment for erosive corneal processes, preliminary results in four patientsKlin Monbl Augenheilkd200021719019311076351

- XieLZhaiHShiWPenetrating keratoplasty for corneal perforations in fungal keratitisCornea200726215816217251805

- RaoGNGargPSridharMSPenetrating keratoplasty in infectious keratitisBrightbillFSCorneal Surgery: theory, technique and tissue3rd edSt LouisMosby1999518525

- FosterCSDuncanJPenetrating keratoplasty for Herpes simplex keratitisAm J Ophthalmol19819233363437027796

- HillJCUse of penetrating keratoplasty in acute bacterial keratitisBr J Ophthalmol19867075025063521719

- TsugitaAOkadaYUcharaKPhotosensitized inactivation of ribonucleic acids in the presence of riboflavinBiochim Biophys Acta196510323603635319746

- GoodrichRPThe use of riboflavin for inactivation of pathogens in blood productsVox Sang200078Suppl 221121510938955

- SamarBMGoodrichRPViral inactivation in plasma using riboflavin-based technologyTransfusion200141Suppl88S

- McAteerMJTay-GoodrichBDoaneSPhotoinactivation of virus in packed red blood cell units using riboflavin and visible lightTransfusion200040Suppl99S

- BesseyOALowryOHFactors influencing the riboflavin content of the corneaJ Biol Chem1944155635646

- MartinsSACombsJCNogueraGAntimicrobial efficacy of riboflavin/UVA combination (365 nm) in vitroInvest Ophthalmol Vis Sci20084983402340818408193

- BaierJMaischTMaierMEngelELandthalerMBaumlerWSinglet oxygen generation by UV-A light exposure of endogenous photosensitizersBiophys J20069141452145916751234

- HirakuYItoKHirakawaKKawanishiSPhotosensitized DNA damage and its protection via a novel mechanismPhotochem Photobiol200783120521216965181

- SpoerlEWollensakGSeilerTIncreased resistance of crosslinked cornea against enzymatic digestionCurr Eye Res2004291354015370365