Abstract

This case report describes the clinical and histopathologic features, including molecular confirmation, of fungal keratitis after intrastromal corneal ring segments placement for keratoconus. A 52-year-old woman underwent insertion of Intacs® corneal implants for treatment of keratoconus. Extrusion of the implants was noted 5 months post insertion and replaced. Three months later, monocular infiltrates and an epithelial defect were observed. The Intacs were removed and the infiltrates were treated with ofloxacin and prednisolone acetate. Microbial cultures and stains were negative. The patient demonstrated flares and exacerbation one month later. Mycoplasma and/or fungus were suspected and treated without improvement. Therapeutic keratoplasty was performed 10 months following initial placement of the corneal ring implants. The keratectomy specimen was analyzed by light microscopy and a panfungal polymerase chain reaction assay. A histopathologic diagnosis of Candida parapsilosis keratitis was made and confirmed by polymerase chain reaction. One year postoperatively, a systemic workup of the patient was done with no signs of recurrence. This rare report of fungal keratitis following Intacs insertion is the first reported case of C. parapsilosis complicating Intacs implantation.

Introduction

Intacs® (Addition Technology Inc, Des Plaines, IL, USA) are intrastromal corneal rings consisting of two thin, clear hexagonal polymethyl methacrylate segments. They are placed in surgically created semicircular channels between the stromal lamella at two-thirds the stromal depth during an outpatient procedure. Intrastromal ring segments work by flattening the central corneal curvature, and are adjustable and reversible. Since receiving approval by the US Food and Drug Administration in 1999, they have been used to correct low to moderate myopiaCitation1 and to treat ectasia following laser in situ keratomileusis.Citation2 Asymmetric implantation of intrastromal corneal ring segments in eyes with keratoconus has been demonstrated to improve both uncorrected and best spectacle-corrected visual acuity, and to reduce irregular astigmatism in corneas with and without scarring.Citation3–Citation7

Relatively few infectious complications have been reported with the use of the intrastromal corneal segments; channel infections have been infrequently documented,Citation1,Citation8–Citation10 and only a limited number of infectious keratitis cases have been reported following insertion of Intacs.Citation8,Citation9,Citation11–Citation16 Although uncommon, microbial keratitis following intrastromal corneal segments insertion is potentially one of the most serious complications and may be sight-threatening. Appropriate suspicion by the eye care provider along with rapid diagnosis and appropriate management can be critical and result in improved visual recovery.

The purpose of this study was to describe the clinical and pathologic features of Candida parapsilosis keratitis, which occurred 8 months following the initially uneventful placement of Intacs inserts for keratoconus. This is the first report in the peer-reviewed literature of C. parapsilosis following Intacs insertion and includes molecular confirmation at the species level.

Case report

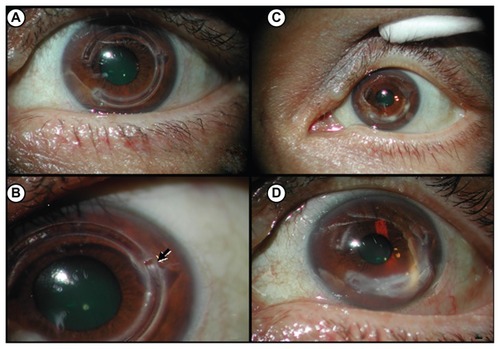

The patient was a 52-year-old female with a history of keratoconus and no known systemic disease or risk factors for infection. Preoperatively, the patient had uncorrected visual acuity of 20/60 OD and 20/200 OS, and best-corrected visual acuity of 20/30 OD and 20/50 OS, with a refraction of −3.00–3.50 × 170 degrees OD and −5.50–4.50 × 20 degrees OS. Intacs intrastromal corneal ring segments were vertically placed in her left eye for treatment of her keratoconus. Specifically, a 35 ring was inserted superiorly and a 45 ring inferiorly through a 65%–70% depth channel. Good visual rehabilitation was obtained following Intacs insertion (uncorrected visual acuity, OS 20/40; best-corrected visual acuity OS 20/25) and was uneventful at 4 months post insertion ().

Figure 1 Slit-lamp photographs of left eye following intrastromal corneal ring segments (Intacs®) insertion. (A) Four months after Intacs insertion. (B) Spontaneous extrusion of inferior Intacs ring implant (arrow) 5 months following original insertion and prior to ring replacement. (C) Initial stromal infiltrates observed 8 months post Intacs insertion (3 months post replacement). (D) Stromal infiltrates at 10 months after initial Intacs insertion and prior to therapeutic keratoplasty.

Spontaneous extrusion of the inferior intrastromal corneal ring segment with no indication of infection was noted 5 months after insertion (), at which time it was removed. The channel was infused with vancomycin solution and a new ring segment was inserted. Eight months post Intacs implantation (3 months post replacement), the location of the lower lateral edge of the intrastromal corneal ring segments showed an epithelial defect and infiltrate on slit-lamp examination (). The size of the epithelial defect and infiltrate was 1 mm and the infiltrate was at a depth of 40%. The intrastromal corneal ring segments were removed because of suspected infection and the infiltrate was treated for 2 weeks with topical ofloxacin 0.3% every 2 hours and prednisolone acetate 1% once daily. Corneal scrapings cultured on blood agar, chocolate agar, thioglycolate broth, and Sabouraud’s agar were negative, as was a Gram stain. The patient was followed weekly and demonstrated flares and exacerbation one month after treatment. The infiltrate progressed into the deep cornea at the level of the intrastromal corneal ring segments at approximately 60% thickness (). Suspecting mycoplasma and/ or fungus, amphotericin B 0.1% every 2 hours, vancomycin 10 mg/mL every 2 hours, and clarithromycin 12 mg/mL every 2 hours were prescribed for one week without improvement. Therapeutic keratoplasty followed to ensure containment of the infiltrate in the central cornea. Intraoperative amphotericin and vancomycin were dropped open sky in the anterior chamber.

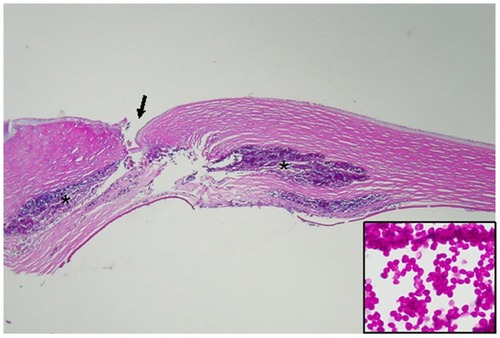

A formal in-fixed keratectomy specimen was histopathologically examined by light microscopy using standard histopathologic techniques, including periodic acid-Schiff staining. The corneal tissue clearly demonstrated insertion channels for the previously removed intrastromal corneal ring segments and a perforating corneal ulcer (). Dense mid-stromal infiltrates and a break in Descemet’s membrane were also noted. As seen in the insert, C. parapsilosis yeast forms have darker staining central nuclei and produce broad-neck buds.

Figure 2 Histopathologic analysis of keratectomy specimen.

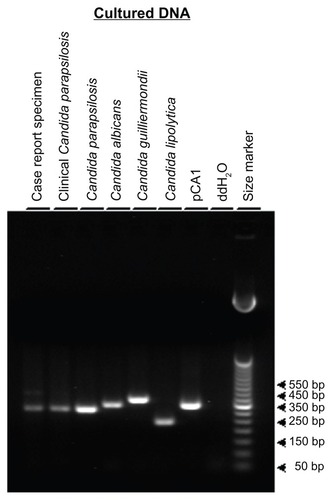

To confirm the histopathologic findings, the corneal tissue was evaluated using a molecular polymerase chain reaction (PCR)-based diagnostic approach. The forward and reverse panfungal PCR primers encompass a highly conserved region of fungal DNA and are designed to amplify and detect a broad spectrum of fungal DNA without amplifying nonfungal DNA.Citation17 The current case report corneal specimen was compared with a previously confirmed ocular case of C. parapsilosis-induced infectious crystalline keratopathy,Citation18 with DNA isolated from various species of Candida grown in culture (), and with plasmid pCA1 DNA that contains a relevant fragment of Candida albicans DNA.Citation17 Formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded clinical corneal specimens were cut with a microtome at a thickness of 10 μm using precautions necessary for PCR analysis. Twelve to 16 microtome sections were placed into sterile microfuge tubes and the DNA extracted using a protocol previously describedCitation19 and modified.Citation20 Overnight cultures of C. parapsilosis, C. albicans, Candida guilliermondii, and Candida (Yarrowia) lipolytica were grown as describedCitation17 and processed for DNA extraction using standard genomic DNA methodsCitation21 with modifications previously described.Citation17 Plasmid pCA1 was grown in Escherichia coli DH5-alpha cells and purified.Citation17 Twenty percent of each DNA sample extracted from the clinical specimens was used for PCR analysis. Approximately 1 × 104 genome equivalents of culture-purified DNA from the control Candida strains and 4 × 104 copies of plasmid pCA1 were used as positive control templates. Deionized distilled water was used as a negative PCR control. The PCR assay conditions had been previously optimized and described.Citation17,Citation22,Citation23 Twenty percent of each PCR assay product was electrophoretically resolved on 1.8% agarose Tris-borate-EDTA gel and visualized using ethidium bromide and ultraviolet excitation. PCR amplicons were compared in size with a 50 bp ladder (Life Technologies, Grand Island, NY, USA).

Table 1 PCR-cultured and plasmid control templates and predicted panfungal PCR product/amplicon sizes

The current keratoplasty specimen produced a PCR amplicon product of approximately 311 bp, as did the crystalline keratopathy corneal specimen and the DNA from cultured C. parapsilosis (). The control DNA from cultured C. albicans, C. guilliermondii, and C. lipolytica produced amplicons of 338 bp, 379 bp, and 242 bp, respectively () in agreement with the predicted sizes (). The plasmid pCA1 containing a fragment of C. albicans DNA produced the predicted 338 bp PCR product, while the negative control showed no amplification product. The molecular results were in complete concordance with the histopathologic findings and diagnosis. The patient underwent a negative systemic workup, and at one year postoperatively had no signs of recurrence.

Figure 3 Panfungal polymerase chain reaction analysis.

Discussion

Intrastromal corneal ring segments are an option in the management of some patients with keratoconus, and their use has been increasing since their efficacy were first reported by Colin et al.Citation5 According to multiple case studies, microbial keratitis occurs as a complication in approximately 1.4%–6.8% of cases post intrastromal ring segments insertion.Citation15,Citation24–Citation26 Infectious keratitis following intrastromal corneal ring segments insertion, while uncommon, is potentially one of the most serious complications. Reported microbial species in post-Intacs keratitis include Staphylococcus aureus, Staphylococcus epidermidis, Staphylococcus viridans, Streptococcus pneumoniae, Streptococcus mitis, Pseudomonas species, Nocardia species, Klebsiella species, Paecylomices species, and Clostridium perfringens.Citation8,Citation9,Citation11,Citation12,Citation15

Ophthalmologists identified C. parapsilosis as a cause for an epidemic of post-cataract endophthalmitis that was linked to intraocular irrigating solutions.Citation27,Citation28 This report demonstrates the potential for C. parapsilosis to be the etiologic cause of infectious keratitis following insertion of corneal ring segments in the treatment of keratoconus. In addition to its link with the endophthalmitis outbreak and with the current case, C. parapsilosis has other ophthalmic associations, such as being the most frequently isolated fungal organism from the normal outer eye in a 1969 study in south FloridaCitation29 and several reports of secondary ophthalmic infections.Citation18,Citation30–Citation38 It has also been linked with crystalline keratopathy in a corneal graftCitation18 and suppurative stromal keratitis.Citation32,Citation39 A large case series suggests that C. parapsilosis accounts for approximately 10% of all causes of yeast keratitis in Southern Florida.Citation32 Recently, C. parapsilosis has been reported as a cause of chronic postoperative endophthalmitis.Citation28,Citation40 Furthermore, C. parapsilosis has emerged as an important nosocomial pathogen with many systemic clinical manifestations in addition to the ocular manifestation of endophthalmitis.Citation41 Overall, C. parapsilosis has accounted for 3%–27% of cases of fungemia in large hospital-based studies.Citation41 Candida and other yeasts are more frequently opportunistic than are filamentous fungi.Citation42 Infections caused by these agents are usually seen in compromised corneas with multiple predisposing alterations in host defense.

Comparison by PCR of the DNA isolated from the current case with various cultured strains of Candida and with previously confirmed C. parapsilosis-infected corneal tissue was consistent with the infecting etiologic agent being C. parapsilosis. The sensitivity and specificity of any molecular diagnostic approach are important parameters for interpretation of assay results. Establishment of the sensitivity and specificity of the current assay has been previously detailed.Citation17 The panfungal primers used bracket a region of the fungal genome encoding the highly conserved 5.8s ribosomal RNA (rRNA), internal transcribed sequence-2 (ITS-2), and 28s rRNA. The sequence specificity and assay stringency conditions allow for sensitive amplification of DNA from a wide variety of fungal strains without amplification of human, bovine, murine, bacterial, or viral DNA. While highly conserved, genomic sequence heterogeneity results in variation of the PCR amplicon/product size depending on the specific fungal strain used as a template source. Candida strains produce PCR amplicons ranging in size from 242 bp to 379 bp () with C. parapsilosis producing a 311 bp PCR product.

This is the first reported case in the peer-reviewed literature of C. parapsilosis keratitis following insertion of intrastromal corneal ring segments. The origin of the Candida, whether from the normal ocular flora or introduced from an exogenous source, is not entirely clear and could not be determined from the current study. While the source is unknown, exposure of the stroma by insertion of Intacs may have allowed ingress of the fungus.

Lipid accumulation on the external side of intrastromal ring segments is common and may complicate the clinical picture of an infectious process. During evaluation of any cornea with intrastromal ring segments, it is important to distinguish between the white color of lipid accumulation and that of an infectious infiltrate. Awareness and consideration of an infectious process being potentially responsible for any white banking is important and may play a critical role in correct diagnosis and subsequent treatment.

Patients should be informed of the risk factors and warning signs of infectious keratitis and should be advised to seek medical attention immediately should they develop signs of symptoms of keratitis. Unlike bacterial keratitis, which can be controlled by potent antibiotics, fungal keratitis is difficult to manage because of the lack of effective antifungal agents, low drug bioavailability, ocular toxicity, decreased solubility, and late presentation with large infiltrates. Long-term postoperative observation following intrastromal corneal ring segments insertion is advocated, especially given that the onset of microbial keratitis post implant can vary from days to months.Citation8,Citation9,Citation11–Citation14,Citation16,Citation43,Citation44 A high degree of suspicion along with appropriate and complete microbiologic testing, coupled with prompt and appropriate treatment, may result in better visual recovery. This case report adds to the growing and diverse list of organisms and presentations of infectious keratitis following insertion of intrastromal ring segments.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported in part by grants from the Retina Research Foundation, Houston, Texas, and Research to Prevent Blindness Inc, New York, NY, USA. RLF is the recipient of the Senior Investigator Award from Research to Prevent Blindness Inc.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- SchanzlinDJAbbottRLAsbellPATwo-year outcomes of intrastromal corneal ring segments for the correction of myopiaOphthalmology20011081688169411535474

- AlioJSalemTArtolaAOsmanAIntracorneal rings to correct corneal ectasia after laser in situ keratomileusisJ Cataract Refract Surg2002281568157412231313

- Boxer WachlerBSChristieJPChandraNSIntacs for keratoconusOphthalmology20031101475

- SiganosCSKymionisGDKartakisNManagement of keratoconus with IntacsAm J Ophthalmol2003135647012504699

- ColinJCochenerBSavaryGCorrecting keratoconus with intracorneal ringsJ Cataract Refract Surg2000261117112211008037

- ColinJCochenerBSavaryGINTACS inserts for treating keratoconus: one-year resultsOphthalmology20011081409141411470691

- KanellopoulosAJPeLPerryHDModified intracorneal ring segment implantations (INTACS) for the management of moderate to advanced keratoconus. Efficacy and complicationsCornea200625293316331037

- BourcierTBorderieVLarocheLLate bacterial keratitis after implantation of intrastromal corneal ring segmentsJ Cataract Refract Surg20032940740912648660

- Shehadeh-Masha’ourRModiNBarbaraAKeratitis after implantation of intrastromal corneal ring segmentsJ Cataract Refract Surg2004301802180415313312

- RuckhoferJStoiberJAlznerEMulticenter European Corneal Correction Assessment Study GroupOne year results of European multicenter study of intrastromal corneal ring segments. Part 2: complications, visual symptoms, and patient satisfactionJ Cataract Refract Surg20012728729611226797

- HashemiHGhaffariRMohammadiMMicrobial keratitis after INTACS implantation with loose sutureJ Refract Surg20082455155218494352

- Hofling-LimaALBrancoBCRomanoACCorneal infections after implantation of intracorneal ring segmentsCornea20042354754915256990

- Ibanez-AlperteJPerez-GarciaDCristobalJAKeratitis after implantation of intrastromal corneal rings with spontaneous extrusion of the segmentCase Report Ophthalmol201014246

- LevyJLifshitTKeratitis after implantation of intrastromal corneal ring segments (Intacs) aided by femtosecond laser for keratoconus correction: case report and description of the literatureEur J Ophthalmol20102078078420155711

- MuletMEPérez-SantonjaJJFerrerCMicrobial keratitis after intrastromal corneal ring segment implantationJ Refract Surg20102636436920506994

- SladeDSJohnsonJTTabinGAcanthamoeba and fungal keratitis in a woman with a history of Intacs corneal implantsEye Contact Lens20083418518718463487

- KercherLWardwellSAWilhelmusKRMolecular screening of donor corneas for fungi before excisionInvest Ophthalmol Vis Sci2001422578258311581202

- RhemMWilhelmusKRFontRLInfectious crystalline keratopathy caused by Candida parapsilosisCornea1996155435458862934

- WrightDKManosMMSample preparation from paraffin-embedded tissuesInnisMAGelfandDHSninskyJJWhiteTJPCR Protocols: A Guide to Methods and ApplicationsSan Diego, CAAcademic Press1990

- MitchellBMFontRLDetection of varicella zoster virus DNA in some patients with giant cell arteritisInvest Ophthalmol Vis Sci2001422572257711581201

- AusubelFMBrentRKingstonRECurrent Protocols in Molecular BiologyNew York, NYJohn Wiley and Sons1995

- YuhaszSADissetteVBCookMLMurine cytomegalovirus is present in both chronic active and latent states in persistently infected miceVirology19942022722808009839

- KercherLMitchellBMImmune transfer protects severely immunosuppressed mice from murine cytomegalovirus retinitis and reduces the viral load in ocular tissueJ Infect Dis200018265266110950756

- FerrerCAlioJLMontanesAUCauses of intrastromal corneal ring segment explantation: clinicopathologic correlation analysisJ Cataract Refract Surg20103697097720494769

- MirandaDSartoriMFrancesconiCFerrara intrastromal corneal ring segments for severe keratoconusJ Refract Surg20031964565314640429

- ShabayekMHAlioJLIntrastromal corneal ring segment implantation by femtosecond laser for keratoconus correctionOphthalmology20071141643165217400293

- O’DayDMHeadWSRobinsonRDAn outbreak of Candida parapsilosis endophthalmitis: analysis of strains by enzyme profile and antifungal susceptibilityBr J Ophthalmol1987711261293493803

- FekratSHallerJAGreenWRPseudophakic Candida parapsilosis endophthalmitis with a consecutive keratitisCornea1995142122167743808

- WilsonLAAheamDGJonesDBFungi from the normal outer eyeAm J Ophthalmol19696752565782862

- SolomonRBiserSADonnenfeldEDCandida parapsilosis keratitis following treatment of epithelial ingrowth after laser in situ keratomileusisEye Contact Lens200430858615260354

- MuallemMSAlfonsoECRomanoACBilateral Candida parapsilosis interface keratitis after laser in situ keratomileusisJ Cataract Refract Surg2003292022202514604730

- RosaRHJrMillerDAlfonsoECThe changing spectrum of fungal keratitis in south FloridaOphthalmology1994101100510138008340

- BourcierTToueauOThomasFCandida parapsilosis keratitisCornea200322515512502949

- SternWHTamuraEJacobsRAEpidemic postsurgical Candida parapsilosis endophthalmitis. Clinical findings and management of 15 consecutive casesOphthalmology198592170117094088622

- McCrayERampellNSolomonSLOutbreak of Candida parapsilosis endophthalmitis after cataract extraction and intraocular lens implantationJ Clin Microbiol1986246256283490490

- GilbertCMNovakMASuccessful treatment of postoperative Candida endophthalmitis in an eye with an intraocular lens implantAm J Ophthalmol1984975935956720838

- StranskyTJPostoperative endophthalmitis secondary to Candida parapsilosis keratitis. A case treated by vitrectomy and intravitreous therapyRetina198111791857348832

- SunRLJonesDBWilhelmusKRClinical characteristics and outcome of Candida keratitisAm J Ophthalmol20071431043104517524775

- TsengSHLingKCLate microbial keratitis after corneal transplantationCornea1995145915948575180

- FoxGMJoondephBCFlynnHWJrDelayed-onset pseudophakic endophthalmitisAm J Ophthalmol19911111631731992736

- WeemsJJJrCandida parapsilosis: epidemiology, pathogenicity, clinical manifestations and antimicrobial susceptibilityClin Infect Dis1992147567661345554

- TanureMACohenEJSudeshSSpectrum of fungal keratitis at Wills Eye Hospital, Philadelphia, PennsylvaniaCornea20001930731210832689

- ChaudhryIAAl-GhamdiAAKiratOBilateral infectious keratitis after implantation of intrastromal corneal ring segmentsCornea20102933934120098317

- GalvisVTelloADelgadoJLate bacterial keratitis after intracorneal ring segments (Ferrara ring) insertion for keratoconusCornea2007261282128418043195