Abstract

Ophthalmomyiasis can have variable presentation depending on the type of fly, structures involved, and level of penetration. A 42-year-old female presented with extensive myiasis of the right eye. A lesion of 3×2 cm was noted at the medial canthus and was infested with maggots. The larvae were removed meticulously and the wound debrided. The larva isolated was that of Chrysomya bezziana (Old World screwworm). Computed tomography (CT) scan was normal. The wound was dressed regularly and healed by secondary intention. Ocular myiasis is a rare disease that can lead to life threatening consequences, such as intracranial extension. Prompt management with debridement and radical antibiotic therapy is essential.

Keywords:

Introduction

Involvement of ocular structures by larvae of dipterous flies is widely known as ophthalmomyiasis. Human ophthalmomyiasis was first reported by Keyt in 1900 and later on by Elliot, in 1910.Citation1 It is predominantly seen in tropical and subtropical regions in countries with poor hygiene, inadequate living conditions, and warm weather. Myiasis in man is found rarely, and eye involvement in human myiasis is less than 5%.Citation2 The parasites most commonly affecting the eye and orbit are the larva of Hypoderma bovis (hornet fly), Oestrus ovis (sheep botfly), and, rarely, by Chrysomya bezziana.Citation3 C. bezziana, also known as Old World screwworm, is an obligate parasite and belongs to the order Diptera, family Calliphyridae, and suborder Cyclorrhpha. As the name suggests, it is distributed throughout much of Africa, the Gulf countries, the Indian subcontinent, and Southeast Asia from People’s Republic of China, through the Malay Peninsula and the Indonesian and Philippine islands to Papua New Guinea ().Citation4

Case report

A 42-year-old female from Dibrugarh, Assam visited us with history of minor injury to the right eye due to fall into a sewer when in a drunken state. She presented 6 days after the injury with chief complaints of swelling, itching, and blood-stained, foul-smelling discharge from the wound. Her husband also noticed small whitish-yellow worm-like structures crawling out from the wound (). She had no significant past history, and systemic examination was normal.

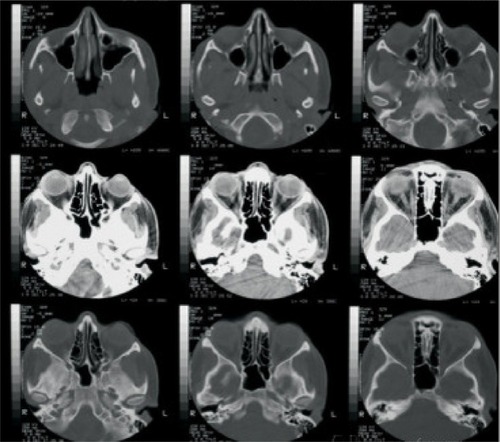

On local examination, best corrected visual acuity of the right eye was 6/18. There was generalized right periorbital edema, with matting of the eyelashes and severe conjunctival vascular engorgement. A lesion of approximately 3×2 cm was noted at the medial canthus. The ulcer had indurated margins with scanty blood-stained, foul-smelling discharge. Small freely moving maggots were visible in the wound. The cornea was hazy, and further detailed examination was not possible. Computed tomography (CT) scan of the orbit showed no signs of bone erosion or paranasal sinus involvement, except for the soft tissue swelling (). The other eye was also examined for maggots and was found to be normal.

Figure 3 CT scan orbit showing no signs of bone involvement, with normal sinuses.

Turpentine oil packing was done to immobilize the maggots. Mechanical debridement of the wound was done, and freely moving maggots were removed with the help of forceps, under local anesthesia using 4% xylocaine (). Regular dressing of the wound was done, with removal of maggots, for next 4 days. The patient was treated with intravenous amoxicillin sodium/potassium clavulanate 1.2 gm given 8 hourly and ibuprofen 400 mg twice daily for 3 days, followed by oral amoxicillin/clavulanic acid 625 mg twice daily for 5 days. A single dose of albendazole 400 mg tablet was also given. Local application of moxifloxacin 0.5% ointment to the right eye for 1 week was advised. The wound started to heal, with granulation tissue formation, and healing was completed by the end of 2 weeks ().

A total of 26 maggots were removed. The maggots were preserved in 10% formalin and sent for entomological evaluation to the Department of Microbiology. The larvae were creamy white in color, with cuticular spines, and varied in size due to different stages of presentation, from 5 to 15 mm. They had strong robust mouth hooks, with four to six papillae on the anterior spiracles, incomplete posterior spiracular peritreme, and pigmented dorsal tracheal trunks in the terminal twelfth larval segment. Based upon these findings they were confirmed to be larvae of C. bezziana (–).

Discussion

Ophthalmomyiasis is mainly manifested as orbital myiasis, ophthalmomyiasis externa (external ocular structure), and ophthalmomyiasis interna (internal ocular structures).Citation5,Citation6 Ophthalmomyiasis externa is characterized by superficial infestation of the ocular tissue and mimics allergic or viral conjunctivitis. Patients complain of pain, burning, itching, redness, and watering in the affected eye, with an abrupt onset, accompanied by sensations of larvae moving in the eye. If timely management is not done, the larvae penetrate the sclera and reach the vitreous and subretinal space, causing ophthalmomyiasis interna as a complication. This manifests as pigmented and atrophic retinal pigment epithelial tracts in multiple crisscross patterns, in conjunction with fibrovascular proliferation, hemorrhage, and exudative detachment of the retina leading to blindness. Maggots can also infiltrate the lacrimal sac and can migrate through the lacrimal canal to the nasal cavity. Extension to the cranial cavity is a possibility, due to the close proximity to the base of the skull.

Normally, healthy individuals are unlikely to suffer from myiasis.Citation7 Chronic debilitating conditions, such as leprosy, diabetes mellitus, open wounds, fungating carcinomas, psychiatric illness, intellectual disability, hemiplegia, and immunosuppressive agents may predispose individuals to myiasis. Infestation with C. bezziana differs from usual maggot infestations because it can invade tissue without preexisting necrotic tissue and cause extensive damage to living tissue if the condition is left undiagnosed. It buries itself deep in the tissue, causes necrosis, and remains firmly attached to it with help of its cuticular spines. The main predisposing factors for the larval infestation in our patient were probably poverty and poor hygiene.

There are 12 species in the genus Chrysomya, most of which are known to cause myiasis in animals. In the literature, only C. bezziana and Cochliomyia hominivorax have been implicated in causing ophthalmomyiasis in living humans.Citation8 The adult fly of Chrysomya is green or blue-green in color and feeds on decaying matter, excreta, and flowers. Approximately 150–200 eggs at a time are laid by the female adult, on exposed wounds and mucous membranes of the mouth, ears, and nose. After 24 hours, eggs hatch, and larvae burrow deep into the living tissue in a screwlike fashion, completing their development while feeding on host tissue for 5–7 days. Thereafter they fall to the ground to pupate. The pupal stage is temperature-dependent, with sexual maturation in approximately 1 week to 2 months. Thus it takes 2–3 months to complete their life cycle.Citation9

C. bezziana has been implicated in cancer-associated myiasis of skin, larynx, face, and breast.Citation10–Citation12 Its involvement in oral myiasis was recorded as early as 1946, in India.Citation13 In a recent report from Iran, C. bezziana larvae caused oral myiasis in an 18-year-old boy with congenital cerebral palsy, quadriplegia, and intellectual disability. It has also been reported as the agent causing urogenital myiasis and otomyiasis. A case of cutaneous myiasis caused by C. bezziana larvae, in a 62-year-old woman who had a complex vascular cutaneous anomaly in her lower right extremity for 8 years, was reported from Mexico in 2010.Citation14

Various methods for removal of the maggots have been documented. The basic principle involves either suffocating the larvae and forcing them out or first paralyzing them followed with mechanical debridement as shown in .Citation15–Citation20 Systemic treatment with broad-spectrum antibiotics, such as amoxicillin with clavulanic acid, metronidazole, and cefazolin are indicated to prevent secondary bacterial infections.Citation21 Antiparasitic drugs such as ivermectin, a semisynthetic macrocyclic lactone, can be used in cases of advanced orbital myiasis, in a dose of 200 μg/kg.Citation22 Ivermectin blocks the nerve impulses through the release of gamma aminobutyric acid (GABA), resulting in palsy and death of larvae.Citation23

Table 1 Agents used in treatment of myiasis

Successful treatment of myiasis depends upon the stage of presentation, severity, and associated predisposing conditions.

Conclusion

Ophthalmomyiasis is an uncommon condition but becomes significant in debilitated and compromised patients. Measures such as general cleanliness of surroundings, maintaining good personal hygiene, provision of basic sanitation, and health education have to be stressed, for preventing myiasis.

Acknowledgments

We thank the Department of Microbiology, Assam Medical College for helping us in identification of the larvae and providing photographs of the same.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- SivaramasubramanyamPSadanandAVOphthalmomyiasisBr J Ophthalmol1968521645635903

- BurnsDADiseases caused by arthropods and other noxious animalsRook’s Textbook of Dermatology2Oxford, UKBlackwell Science11th ed201233.133.63

- Lagacé-WiensPRDookeranRSkinnerSLeichtRColwellDDGallowayTDHuman ophthalmomyiasis interna caused by Hypoderma tarandi, Northern CanadaEmerg Infect Dis2008141646618258079

- SutherstRWSpradberyJPMaywaldGFThe potential geographical distribution of the Old World screw-worm fly, Chrysomya bezzianaMed Vet Entomol1989332732802519672

- KhataminiaGAghajanzadehRVazirianzadehBRahdarMOrbital myiasisJ Ophthalmic Vis Res20116319920322454736

- SigaukeEBeebeWEGanderRMCavuotiDSouthernPMCase report: ophthalmomyiasis externa in Dallas County, TexasAm J Trop Med Hyg2003681464712556147

- Duke-ElderSSystem of Ophthalmology1St Louis, MOMosby1958

- KhuranaSBiswalMBhattiHOphthalmomyiasis: Three cases from North IndiaIndian J Med Microbiol201028325726120644320

- WalkerARThe Arthropods of Human and Domestic Animals. A Guide to Preliminary IdentificationLondonChapman & Hall1994

- HawayekLHMutasimDFMyiasis in a giant squamous cell carcinomaJ Am Acad Dermatol200654474074116546611

- RubioCLadrón de GuevaraCMartínMACamposLQuesadaACasadoMCutaneous myiasis over tumor-lesions: presentation of three casesActas Dermosifiliogr20069713942 Spanish16540050

- KwongAYiuWKChowLWWongSChrysomya bezziana: a rare infestation of the breastBreast J200713329730117461907

- GrennanSA case of oral myiasisBr Dent J19468027421024954

- Romero-CabelloRCalderón-RomeroLSánchez-VegaJTTayJRomero-FeregrinoRCutaneous myiasis caused by Chrysomya bezziana larvae, MexicoEmerg Infect Dis201016122014201521122252

- AshenhurstMPietuchaSManagement of ophthalmomyiasis externa: case reportCan J Ophthalmol200439328528715180148

- SwetterSMStewartMISmollerBRCutaneous myiasis following travel to BelizeInt J Dermatol19963521181208850041

- De TarsoPPierre-FilhoPMinguiniNPierreLMPierreAMUse of ivermectin in the treatment of orbital myiasis caused by Cochliomyia hominivoraxScand J Infect Dis2004366–750350515307583

- RichardsKABrievaJMyiasis in a pregnant woman and an effective, sterile method of surgical extractionDermatol Surg2000261095595711050502

- BrewerTFWilsonMEGonzalezEFelsensteinDBacon therapy and furuncular myiasisJAMA199327017208720888411575

- MandellGLBennettJEDolinRInfectious diseases and their etiologic agentsPrinciples and Practice of Infectious Diseases25 edPhiladelphia, PAChurchill Livingstone200029762979

- AsokanGSAnandVBalajiNParthibanJJeelaniSMaggots in the mouth–oral myiasis: a rare case reportJ Indian Aca Oral Med Radiol2013253225228

- CampbellWCIvermectin: an updateParasitol Today198511101615275618

- OsorioJMoncadaLMolanoAValderramaSGualteroSFranco-ParedesCRole of ivermectin in the treatment of severe orbital myiasis due to Cochliomyia hominivoraxClin Infect Dis2006436e57e5916912935