Abstract

Penetrating injury of the skull and brain are relatively uncommon events, representing about 0.4% of all head injuries. Transorbital penetrating brain injury is an unusual occurrence in emergency practice and presents with controversial management. We report the case of a 10-year-old boy who fell forward on a bamboo stick while playing with other children, causing a penetrating transorbital injury, resulting in meningitis. We performed a combined surgical approach with neurosurgeons and ophthalmogic surgeons. Upon discharge, the patient had a Glasgow Coma Scale score of 15, no motor deficit and no visual loss. We discuss the management of this case and review current literature.

Introduction

Accidental penetrating wounds of the brain are relatively uncommon in western countries with the adult calvarium usually providing an effective barrier against such lesions.Citation1,Citation2 However, there are areas of thinner bone, such as the temporal region, where a wide variety of objects have been reported involving penetrating wounds. Penetrating head injuries are usually caused by relatively high-velocity penetration by metal objects.Citation3–Citation5

Transorbital penetrating brain injury is an unusual occurrence in general neurosurgical practice and presents with controversial management. We report the case of a child who suffered a transorbital penetrating head injury caused by a bamboo fragment resulting in meningitis and discuss management of the injury and review the current literature.

Case report

A 10-year-old boy fell forward on a bamboo stick while playing with other children, resulting in a penetrating transorbital injury. Snellen visual acuity test showed decrease on light perception on the left eye, 20/20 perception on the right eye. Physical examination by the ophthalmology team revealed a simple supraorbital wound; the eyeball was intact but with periorbital edema and conjunctival ecchymosis. Upon arrival to first trauma center the patient was conscious and completely responsive with a Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS) score of 15 points, and he followed commands appropriately. The movement of the eye was compromised on admission, but improved markedly after a few days, normalizing with the regression of periorbital edema. The patient was initially evaluated in another service, where a simple dressing was performed on the supraorbital wound prior to discharge.

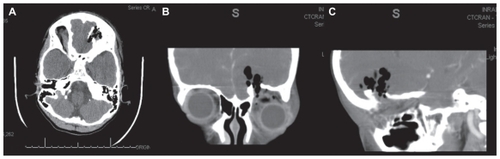

One day after trauma, the child was admitted to our unit with fever, conscious, without cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) fistula. Patient underwent skull and orbital computed tomography which showed a roof of orbit fracture, with pneumocranium. No foreign body was observed with computed tomography (CT) ().

Figure 1 CT scan of skull axial (A), coronal (B), and sagittal (C) of the head showing a fracture of the orbital roof and speck of pneumocephalus, however no foreign bodies can be verified in this case involving wood fragment on CT examination.

In the blood cell count, leukocytes were 18000/mm3 including neutrophils (87%). Lumbar puncture showed counts of leukocytes (2960/mm3) and red blood cells (933/mm3), protein count (0.99 g/L), and glucose (45 mg/dL). Intravenous antibiotics (oxacillin and cephtriaxone) were prescribed.

Two days later the patient presented with repeated fever and a new CSF sample was obtained, which showed an increased leukocyte count (5040/mm3), and decreased glucose levels (24 mg/dL). At this moment, we decided to perform a combined surgical approach with ophthalmic surgeons. The ophthalmology team used a supraorbital approach, attaining removal of bamboo fragments; the largest one measuring up to 2 cm. Simultaneously the neurosurgical team performed a frontal craniotomy exposing the orbital roof and superior sagittal sinus, to facilitate lifting of the frontal lobe and inspection of the root of the orbit and cribriform plate. During the surgery we observed a 15 mm-long wound parallel to the left rim of the orbit, filled herniated orbital fat. CSF fistula (dural laceration caused by bone fragments) was also observed in the posteromedial region of the left orbital wall, formed by the frontal bone. The neurosurgical team then cleaned the wound and corrected the dural lesion with pediculated flap of pericranium and fibrin glue. The initial antibiotic prescription was modified to vancomycin and cephepime. Culture was sterile. The patient presented with a favorable outcome, without CSF fistula. The image of pneumocranium at the CT disappeared one week after surgery and a left frontal hypodense image that was not enhanced by intravenous contrast agent was verified. Intravenous antibiotic treatment was maintained for 3 weeks until discharge. Upon discharge, the patient had a GCS score of 15, no motor deficit and no visual loss.

Discussion

Penetrating injury of the skull and brain are relatively uncommon wounds, representing about 0.4% of all head injuries.Citation5 Although some authors have reported penetrating craniocerebral injuries caused by foreign bodies during wartime and civilian incidents.Citation3–Citation6 Orbitocranial injuries caused by high-speed projectile foreign bodies are quite unusual events, however, penetrating traumatic brain injury with low-energy trauma is even rarer. Cranial trauma encompasses a spectrum of initial presentations. Most penetrating cranial injuries, regardless of the size of the penetrating bodies, are rarely associated with major neurological symptoms, except in high velocity injuries, which are usually associated with major neurological symptoms.Citation1

Neurological examination may show a normal picture in the first hours immediately after trauma even when both intracranial hematoma and intracerebral foreign body are present.Citation7 When there is a suspicion of transorbital penetration, the clinical examination must be supplemented by orbital and cerebral CT scan with both axial and coronal sections of the orbit. The most frequent path of penetration is through the orbit roof due to the fragile structure of the superior orbital plate of the frontal bone.Citation8

Treatment of transorbital penetrating injury aims to immediately save life through control of persistent bleeding and intracranial hypertension, prevention of infection through debridement of all contaminated and necrotic tissues, preservation of as much nervous tissue as possible, and restoration of anatomic structures through accurate closure of the dura and scalp.Citation1 Currently, surgical management of these lesions tend towards minimizing the degree of debridement, preserving as much cerebral tissue as possible, and removing the bone fragments and foreign body if easily accessible, It is crucial to prevent the foreign body from involuntary movement otherwise it can enlarge the damaged area.

Early surgical exploration is likely to be successful in cases of retained foreign body. A transorbital or transcranial approach can be chosen depending on the location of the fragment.Citation9 We believe that after adequate resuscitation, the goal of surgery is safe removal of the object without further damage to the brain, debridement of bone fragments, hair, and other debris from the brain, evacuation of hematoma, meticulous hemostasis, removal of devitalized brain with preservation of all viable brain tissue, and appropriate repair and closure of the dura and scalp wound.

Transorbital injury management is complex and is historically seen as a challenge. Even now, the medical community is still intrigued by the injury to Phineas Gage.Citation10 The injury occurred in 1848 when a premature explosion at a railroad construction site drove a tamping iron through the left orbit and frontal lobes of the 25-year-old foreman, presenting significant behavioral changes. The frontal lobes control personality, judgment, emotion, planning, initiation, execution, and other higher cognitive functions.Citation11 These frontal lesions can result in serious behavioral consequences as in the case of Phineas Gage. In our patient we believe that limiting the brain damage may be responsible for the absence of major cognitive impairments.

In a literature review of about 150 papers dealing with penetrating intracranial injuries, we verified many cases of transorbital intracranial injuries that were not diagnosed early, resulting in further complications over time as in our patient. We believe that in patients presenting with transorbital penetrating injury, emergency doctors must have a high index of suspicion towards every case including wounds that may seem trivial. We also would like to stress that when fragments of wood are involved the risk of intracranial injuries, including vascular as well as infectious complications (meningitis, abscesses, or empyema) can appear days, weeks, or months after the trauma.Citation12 The clinical state immediately after the penetrating trauma is very often surprisingly good and the GCS high as the extent of cerebral damage could be focused to the area of stab injury in contrast to diffuse closed head injury. Therefore, the prognosis of such trauma can be quite promising in cases where there are no serious complications. Obviously, the main limiting factor is the extent of brain tissue laceration. We believe that early diagnosis and treatment are essential for a good outcome.

Conclusion

In patients with transorbital penetrating injury, the emergency doctors must have a high index of suspicion towards the presence of foreign bodies, and should more commonly consider an aggressive approach when involving wood fragments, in spite of consistent lack of such evidence on CT.

Disclosure

No conflicts of interest were declared in relation to this paper.

References

- PaivaWSSaadFCravalhalESAmorimRLFigueiredoEGTeixeiraMJTransorbital stab penetrating brain injury: report of a caseAnn Ital Chir200980646346520476680

- IwakuraMKawaguchiTHosodaKShibataYKomatsuHYanagisawaAKnife blade penetrating stab wound to the brain: case reportNeurol Med Chir (Tokyo)200545317217515782012

- BauerMPatzeltDIntracranial stab injuries: case report and case studyForensic Sci Int2002129212212712243881

- DomenicucciMQashoRCiappettaPVangelistaTDelfiniRSurgical treatment of penetrating orbito-cranial injuries. Case reportJ Neurosurg Sci199943322923410817393

- GennarelliTAChampionHRSaccoWJCopesWSAlvesWMMortality of patients with head injury and extracranial injury treated in trauma centersJ Trauma198929119312012769804

- KitakamiAKirikaeMKurodaKOgawaATransorbital-transpetrosal penetrating cerebellar injury – case reportNeurol Med Chir (Tokyo)199939215015210193148

- AgrawalAPratapAAgrawalCSKumarARupakhetiSTransorbital orbitocranial penetrating injury due to bicycle brake handle in a childPediatr Neurosurg200743649850017992039

- LinHLLeeHCChoDYManagement of transorbital brain injuryJ Chin Med Assoc2007701363817276932

- MatsuyamaTOkuchiKNogamiKHataMMuraoYTransorbital penetrating injury by a chopstickNeurol Med Chir (Tokyo)20014134534811487998

- BigelowHJDr Harlow’s case of recovery from the passage of an iron bar through the headAm J Med Sci1850201322

- OrdiaJIBrain impalement by an angle metal barClin Neurol Neurosurg2009111436837219091457

- LeeJHKimDGBrain abscess related to metal fragments 47 years after a head injury: case reportJ Neurosurg20009347747910969947