Abstract

Background

Asthma is common among children, adolescents, and adults. However, management of asthma often fails to follow evidence-based guidelines. Control assessments have been developed, validated against expert opinion, and disseminated. However, in primary care, assessment of control is only one step in asthma management. To facilitate integration of the evidence-based guidelines into practice, tools should also guide the next steps in care. The Asthma APGAR tools do just that, incorporating a control assessment as well as assessment of the most common reasons for inadequate and poor control. The Asthma APGAR tool is also linked to a care algorithm based on the 2007 National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute asthma guidelines. The objective of this study is to assess the impact of implementation of the Asthma APGAR on patient asthma outcomes in primary care practices.

Methods

A total of 1400 patients aged 5–60 years with physician-diagnosed asthma are enrolled in 20 practice-based research network (PBRN) practices randomized to intervention or usual care. The primary outcomes are changes in patient self-reported asthma control, asthma-related quality of life, and rates of exacerbations documented in medical records over the 18–24 months of enrollment. Process measures related to implementation of the Asthma APGAR system into daily care will also be assessed using review of medical records. Qualitative assessments will be used to explore barriers to and facilitators for integrating the Asthma APGAR tools into daily practice in primary care.

Discussion

Data from this pivotal pragmatic study are intended to demonstrate the importance of linking assessment of asthma and management tools to improve asthma-related patient outcomes. The study is an effectiveness trial done in real-world PBRN practices using patient-oriented outcome measures, making it generalizable to the largest possible group of asthma care providers and primary care clinics.

Introduction

Asthma affects as many as 18% of US children by the age of 18 years and 5% of adults, with another 5% of children and adults reporting exercise-induced asthma.Citation1–Citation7 Asthma is the 15th most common condition seen by family physicians,Citation8 and the majority of the 11.9 million annual asthma-related medical visits are made to primary care physicians.Citation2,Citation3,Citation9–Citation11 Asthma is associated with significant morbidity and mortality,Citation3,Citation12–Citation16 much of which could be preventedCitation17–Citation19 by broader implementation of the four major tenets of the 2007 National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NHLBI) asthma guidelines.Citation20–Citation28 These tenets include accurate diagnosis, appropriate treatment, ongoing monitoring and assessment, and developing partnerships between health professionals and families.Citation29–Citation34 Simple tools have been developed to monitor asthma control.Citation35–Citation45 However, none of the control scores recommended in the US guidelines are linked to the next steps of asthma care.Citation7,Citation21,Citation43,Citation46–Citation49

Asthma is a chronic inflammatory disease with overlying acute episodes of increased inflammation and bronchoconstriction.Citation18 Determining how to specify, address, and prevent the inflammation of asthma better is the major therapy question, while the translational question of most importance is how to facilitate, operationalize, systematize, and integrate guideline-directed care into everyday practice.Citation7,Citation43,Citation46–Citation48,Citation50,Citation51

Assessment of asthma “control” requires knowledge of the patient’s symptom burden, eg, daytime and night-time symptoms and need to modify activities. Primary care medical records consistently lack this information.Citation7,Citation43,Citation46,Citation47,Citation50,Citation52 Existing highly promoted control assessments collect the information to assess control.Citation21,Citation22,Citation46,Citation47,Citation52 The control assessments leave the patient labeled as in or out of control and may predict future exacerbations, but provide no further guidance related to therapy. Primary care physicians need systems and tools to guide daily practice and not just to label or risk-stratify patients.

Therefore, asthma remains an important target for translational studies and testing of tools that facilitate all four of the NHLBI’s major tenets of asthma care.Citation18 The Asthma APGAR system uses tools developed, validated, and demonstrated to work in primary care practices. This multicomponent system includes audit with feedback and patient-reported signs and symptoms, as well as information on adherence, triggers, and response to therapy in a system that allows flexibility and adaptability in implementation.Citation54,Citation55 This clinical trial assesses the effectiveness of the Asthma APGAR systemCitation54 in primary care, focusing on patient-oriented asthma outcomes. The trial is being done at community practice-based research network (PBRN) primary care sites to enhance the generalizability of the results while maintaining adequate internal validity.Citation56–Citation60

Materials and methods

Overview

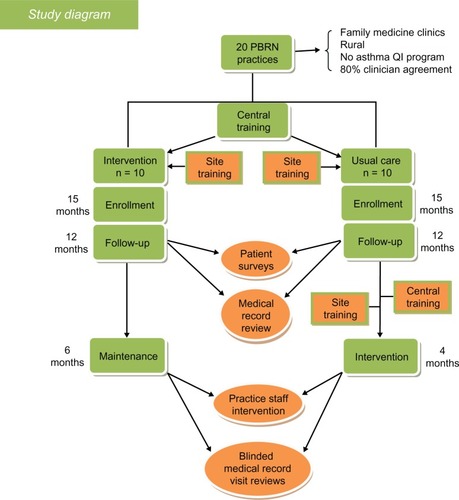

This is a pragmatic, randomized, controlled effectiveness trial () of a practice system change for asthma evaluation and management and is now presently underway in 20 family medicine and pediatric practices (all members of the PBRN). Randomization was 1:1 (intervention to usual care) and stratified by residency status (yes or no) and type of practice (pediatric or family medicine practice). A total of 1400 patients are to be enrolled. The primary outcomes will be changes in self-reported asthma control, self-reported quality of life, and rates of asthma exacerbations documented by medical records. Secondary outcomes are care process measures, including documentation of asthma control, education on or review of inhaler technique, and assessment of adherence during clinic visits. Exploratory outcomes will be assessed using qualitative methods (semistructured interviews) to explore factors associated with the feasibility of implementing Asthma APGAR tools in the intervention practices.

Figure 1 Study design.

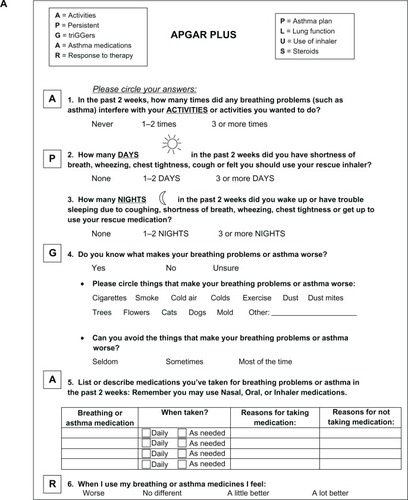

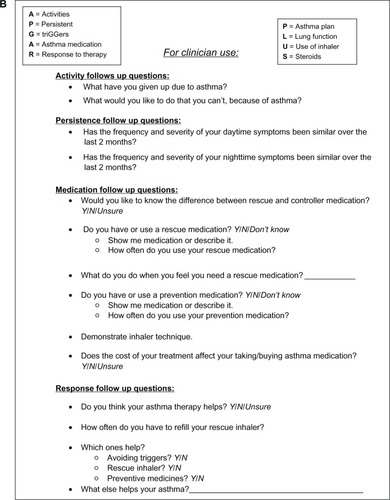

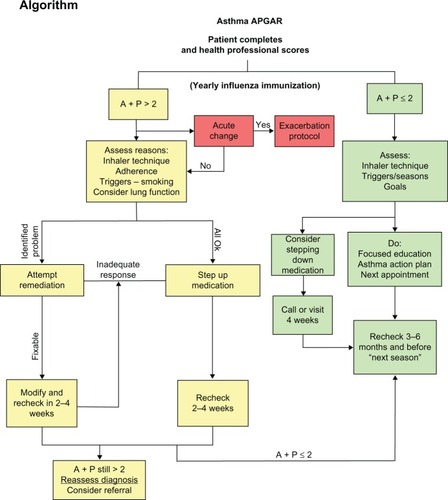

The intervention consists of a facilitated practice systems change to integrate the Asthma APGAR tools into daily management of asthma. The Asthma APGAR tools address five domains critical to the tracking, assessment, monitoring, and management of asthma (). The Asthma APGAR tools include: a five-question practice asthma care audit used to motivate, monitor, and report baseline asthma care processes (); a patient-completed survey issued at all asthma visits to assess and track control as well as explore the most common reasons for lack of control (); and a care algorithm linked to the control, adherence, and trigger assessment using evidence from the 2007 NHLBI asthma guidelines (). The algorithm incorporates both drug and nondrug management strategies, eg, stepped medication care, asthma education, and evaluation of inhaler technique. The intervention tools have been pretested and validated to change and sustain processes centered on the Asthma APGAR tools.Citation54 Use of the tools has been shown to facilitate guideline-adherent asthma care and should thereby improve patient outcomes.

Table 1 APGAR domains: essential elements

Practices

The practices enrolled are members of the American Academy of Family Physicians National Research Network (http://www.aafp.org/nrn) or the American Academy of Pediatrics Quality Improvement Innovation Network (http://www.aap.org/en-us/professional-resources/practice-support/quality-improvement/Quality-Improvement-Innovation-Networks/Pages/Quality-Improvement-Innovation-Networks-QuIIN.aspx).

Inclusion criteria

Practice located in a non-inner city or urban center with >250,000 population

Practice includes 2–12 primary care clinicians

Within the practice, 80% of all primary care physicians agree to participate in the project for three years

Practice has had at least 100 patients aged 5–60 years making asthma visits in past 12 months

Practice agrees to recruit at least 70 patients with asthma over the 15-month enrollment period of the study

Practice is willing to sign an individual investigator agreement with the American Academy of Family Physicians institutional review board or have an affiliation with a local institutional review board.

Exclusion criterion

Practice has been involved in any formal asthma care improvement program during the previous three years.

Each practice signed a practice agreement attesting to the support of the practice leadership and acknowledging the $1300 per year they would receive based on attaining specific enrollment goals and copying and mailing of medical records goals. Practices were not and could not be blinded to their randomization status. However, the patients who are enrolled will not know the randomization status of the practice they attend.

Patients

Patients are recruited in two ways, ie, as they are seen in the enrolled practices for a patient visit or by identification from an asthma registry and an invitation to come for an asthma checkup and enrollment in the study. The enrollment process is the same for patients in an intervention or a usual care practice.

Inclusion criteria

Patient is aged 5–60 years

Patient has a physician diagnosis of asthma and a current prescription for an asthma drug

Patient or parent agrees to complete the five study packets (baseline, and at 6, 12, 18, and 24 months after enrollment) and allow review of the enrollee’s medical record by the central study team members.

Exclusion criteria

Patient or parent is unable to read or speak English

Patient has a concomitant diagnosis of cystic fibrosis, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), or other chronic lung disease.

Children younger than 5 years of age are excluded to avoid the problem of diagnostic uncertainty often found in preschool children.Citation61,Citation62 Adults over 60 years of age were also excluded because of concerns about COPD that has been misdiagnosed as asthma.Citation63 Treatment for cystic fibrosis, COPD, active tuberculosis, or other chronic lung disease is significantly different from that recommended for asthma, and inclusion of these patients could confound our results. Spirometry is not required because it is unlikely to be available in most of the primary care practices enrolled and because most asthma seen in primary care is diagnosed on the basis of symptoms and response to therapy.Citation64–Citation66

Study procedures

Site training

Two members from each practice (a lead study physician and a lead nurse) were brought together at a central site to introduce the study procedures to all sites and the Asthma APGAR system to the intervention sites. Training on the study procedure lasted eight hours, beginning with a short overview of the 2007 NHLBI asthma guidelines. The remainder of the day focused on methods to identify asthma patients for potential enrollment, informed consent, tracking forms to assess enrollment and refusal rates, and methods (e-faxing and faxing) used to send study data to the central site. An opportunity to complete the required human subjects training was included.

The intervention site training continued with six hours of work on the next day. That time was used to introduce the Asthma APGAR tools and to discuss and demonstrate how they could be integrated into daily asthma care. Interaction methods included case presentations, discussion, and interactive brainstorming of ways to facilitate use of the Asthma APGAR. Because implementation of the intervention includes some flexibility, time was spent working with each practice team individually to discuss practice-specific implementation. Each team was provided with an arm-specific slide presentation designed to be used by the team leaders at an all-practice local study training session. The slides included a shortened version of the information presented during central training. The principal investigator for the study attended all of these local training sessions by telephone conference call to lend support and answer questions.

Implementation at intervention sites

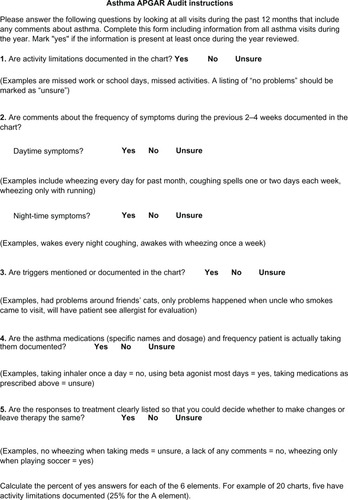

Based on experience from previous work, introduction of the Asthma APGAR system in the intervention practices was accompanied by “motivational” work to improve practice engagement in the project. Each practice’s current asthma care was evaluated using the Asthma APGAR audit which assesses the presence or absence of documentation in selected medical records of the elements required to evaluate asthma control ().

These audit data were summarized, graphed, and presented to the entire practice staff as part of the local study training led by the site lead physician and nurse as described above. One goal of the sessions was to help the practices assess the strengths and gaps in asthma care before initiating the study. Strengths were discussed first.

By including discussion of what the practice does well, discussion appeared to begin more readily than when focusing first on gaps. When discussing gaps, invariably one or two clinicians pointed out they had done much more than was documented. These comments facilitated discussion on the purpose of the information documented in the medical record and its use, not only at the current visit but also during future visits to assess changes in asthma status over time. Guided discussion also addressed the potential value of the Asthma APGAR data elements () in identifying reasons for inadequate control, such as the role of triggers, adherence, and medication failures in asthma control.

Introducing a new tool into practice requires planning and often trial and error. All intervention practices were allowed a six-week period to adapt implementation of the Asthma APGAR into their practice before adding the additional burden of patient enrollment. No specific study visits are required in this pragmatic trial. When patients do visit the clinic for any reason, they receive the patient Asthma APGAR survey. The Asthma APGAR information is used and documented as the physician/clinician chooses during each visit.

A coordinator from the central study team is assigned to each practice as the practice liaison. The liaison interacts with the site nurse leader weekly during the early implementation phase and then biweekly or as needed throughout the rest of the study.

Usual care group

After returning home from central training, the usual care study leaders also provide a short education session for their practice members. The focus of the education session is “whole practice participation” in identifying patients eligible for enrollment and assuring that all practice staff are aware of the study. As in the intervention program, no visits or visit frequency is dictated by the study. All care decisions are at the discretion of the physician/clinician and patient. Usual care sites are also assigned a liaison from the central study team to work with the local sites on patient enrollment.

Patient-reported outcomes

Patient or parent subjects are asked to complete five survey packets at baseline and at 6, 12, 18, and 24 months after enrollment. Each packet includes the Patient Assessment of Chronic Illness Care (PACIC), the Asthma Quality of Life Questionnaire/Pediatric Asthma Quality of Life Questionnaire (AQLQ/PAQLQ), the Asthma Control Test (ACT), Asthma APGAR patient questions, and a group of health care utilization questions (). The initial packet also includes demographic data. To facilitate continued participation in the study, a central site coordinator calls each enrolled person (or parent) within 72 hours of signing the informed consent.

Table 2 Variables, instruments, and links to study aims

Practice process data

Medical record data are required to measure practice asthma care processes and to assess asthma exacerbation rates. All data abstraction is done centrally. Inter-rater reliability testing will be accomplished within each site and across sites and must remain at 90% or greater. This will be done by abstraction of the same record by multiple abstractors across and within sites. If agreement is lower than 90% for at least five major items within the abstraction, additional training and testing will be undertaken.

Fidelity measures

Translational and effectiveness studies differ from efficacy and traditional randomized controlled trials in that no central study staff are present in the study practice sites. Therefore, it is important to have some measure of how well the intervention is actually implemented, ie, a study fidelity metric. In this study, uptake of the intervention is assessed using mixed methods, including semistructured interviews with the lead physician and nurse at the study site and medical record review at the end of the study period to assess documentation of use of the Asthma APGAR tools.

Exploratory data concerning barriers and facilitators

The central site staff will conduct interviews to collect information on use of the Asthma APGAR tools. Each interviewee will be queried regarding barriers and facilitators of the Asthma APGAR implementation.

Data analysis

The patient data will be summarized and presented in both graphic and tabular form, separately by site and pooled intervention versus control. The primary patient-oriented outcomes will be analyzed using linear mixed effects or generalized linear random effects models, with random mean terms for patient and practice, and fixed-effect terms for patient age and gender, and a fixed-effect term for the intervention. For these patient outcomes, the random effects for practices are likely to be important, given that there are likely to be fairly large differences in patient characteristics across different practices.

Whenever patient-reported outcomes are used, some level of nonresponse is expected. To minimize the number of records excluded from analysis, we will use multiple imputations to fit missing responses. Results of the multiple imputation analysis will be compared with an analysis of complete data; if results differ, both will be presented.

The ACT and AQLQ/PAQLQ scores are reasonably Gaussian, and we will fit linear models for them. For asthma exacerbations and number of missed work/school days, we will fit generalized mixed linear models with a random effect term to adjust for differences between practices. A significant coefficient for the intervention term will be interpreted as indicating an intervention effect. For assessment of exacerbations (requiring short bursts of oral steroids), data are only relevant for those visits dealing with exacerbations. Therefore, for this measure, analysis will be restricted to those visits where that treatment is appropriate.

Information from visits will be compared between intervention and control practices starting at three months, to allow a run-in period for the intervention to be implemented. Per-practice rates for each of these procedures will be computed both before (baseline data) and after the three-month run-in period (study period), and will be presented in both graphic and tabular form. The hypotheses for the five measures will be tested through logistic regression with random effects (generalized linear mixed models), with random mean terms for patient and practice, fixed-effect terms for patient age and gender, and a fixed-effect term for the intervention. Baseline data obtained from both the intervention and control practices will be included in the models, but the visit-specific value for the intervention term will be 0 (not intervention) for these records, because at that time the intervention would not yet have been implemented. Inclusion of baseline data will allow good estimation of practice random effects, and will adjust for differences not accounted for by randomization. A significant coefficient for the intervention term will be interpreted as evidence of an intervention effect.

The number of asthma-related practice systems in place for each practice will be assessed at time 0 and at 24 months using the PACIC modified for asthma care. In each of the six domains, three clinically important types of system will be identified, so the number of new systems could range from 0 to 18. The within-practice number of new systems will be computed by subtracting the number of systems in place at study completion from baseline, and will be compared across practices using the Wilcoxon rank-sum test. The PACIC is a patient visit-level measure that we are using to quantify the practice-level intervention effect.Citation67 Its distribution is approximately Gaussian, and we will fit a linear random effects model, with random mean terms for patient and practice, fixed-effect terms for patient age and gender, and a fixed-effect term for the intervention. Inclusion of the baseline data will allow good estimation of the practice random effects, and will adjust for differences not accounted for by randomization. A significant coefficient for the intervention term will be interpreted as evidence of an intervention effect.

Analysis of the key personnel interviews will be descriptive and exploratory. We will attempt to identify any unanticipated barriers and facilitators to implementation. In addition, the interviews will provide information about underused or ineffective systems.

Sample size

We will enroll approximately 1400 patients, averaging 70 per practice. In our study of post-partum depressionCitation40 we were able to attain 12-month response rates better than 60%; this group of asthma patients is likely to be less mobile, and we believe that assuming a 60% complete response is conservative. Based on simulated data with 840 subjects, we estimate that we will have over 80% power to detect a change in exacerbation rate from 12% to 8%, and over 90% power to detect a difference between a mean of 5.0 versus a mean of 4.0 missed work/school days. For the AQLQ/PAQLQ, the overall score is approximately Gaussian with a standard deviation of about 0.8;Citation68 we will have approximately 80% power to detect a mean difference of 0.15. A difference of 0.5 represents an important clinical change for an individual.Citation69

Discussion

Effectiveness and PBRN translational studies are different from efficacy studies and clinical trials based at academic centers.Citation58–Citation60,Citation70–Citation75 Not only is the subject and goal usually different, but the study design must be built around the strengths and weaknesses inherent in doing research in a real-world practice. In national studies, it is rarely feasible to send research coordinators or facilitators to each of the study sites on a repeated basis.Citation57,Citation76 Therefore, the study must be designed in a manner that allows the study personnel to carry out the study with limited use of practice resources. This difference is highlighted in the sections on study and intervention implementation. The all-practice meetings led by the two practice leaders are supported heavily by the central team, and include development and dissemination of pre-prepared educational slide programs and handouts, the simple practice audit, and a proven format in which to present the audit data. Telephone support from the principal investigator and the central site lead study coordinator demonstrates the central team’s commitment to provide help at each stage of the study.Citation77 The provision of a study liaison for continuity of contact has resulted in local sites identifying with their liaison and funneling their questions and concerns through a single individual. Making sure that all interactions with practices are at all times convenient for the practices not the principal investigator or central study team is necessary to engage the local sites. Unlike many large clinical trials, there can be no expectation that a PBRN study comes ahead of any clinical or practice issue. Familiarity with practice flow and challenges in sites similar to those enrolled in the study facilitates discussion and keeps expectations of the central site in line with those of the enrolled sites. Certain issues can be anticipated in all PBRN studies, and are discussed in the following sections.

Time pressures

Time pressures will be an issue for these practices. Meetings with the central study staff will be held by distance interaction (telephone or web-based) at a time that is convenient for the practice. Each practice will be paid $1300 in each of the study years. This will not cover their time or effort, but does serve to recognize the important contributions of the practice. We will limit staff time away from or interference with patient care as far as possible.

Practice politics

It can be difficult to engender open and honest discussion in some practices or suggest that baseline care is not of the highest quality. To avoid including practices with no hope of collaboration, we will query each practice about previous attempts at practice change and ask for assurance that at least 80% of their primary care physicians are committed to this study.

Reluctance to use asthma guidelines

The Asthma APGAR is designed to make it feasible to use the guidelines in practices that have previously been unable or unwilling to do so.

Lack of resources to make practice changes

We anticipate that our concepts and tools will minimize such difficulties and may even make the care of asthma easier in these practices.

Failure to institutionalize changes

Many previous quality improvement efforts have suffered from the mentality of “fix it and move on”, that often results in a decline in practice systems or process improvement and potentially in the quality of care. We will test the level of the Asthma APGAR’s sustainability and practice institutionalization by including a maintenance phase, which is similar to the intervention phase but without support or calls from the central site staff.

This study has limitations that must be recognized in its initial design and goals. The study will occur in practices that do not have the research personnel usually associated with a randomized controlled trial. This is an advantage for generalizability of the results, but might be viewed as a limitation by those only familiar with trials of efficacy conducted in carefully controlled environments. With careful monitoring, frequent contact, and collection of fidelity data, PBRNs have been shown to be capable of producing reliable and accurate effectiveness results.Citation57 Asthma is defined clinically, and no pulmonary function data are required. Many of the enrolled practices do not have experience with spirometry testing. This is comparable with the 40%–60% of all primary care practices in the US that do not use spirometry on a regular basis. Other researchers, such as JuniperCitation39 and Nathan et al,Citation37 have found that assessment of asthma control and patient outcomes is possible without pulmonary function testing. This study will be generalizable to the defined asthma population of most primary care practices. Outcomes assessment will rely heavily on patient self-reporting of asthma control and asthma-related quality of life. Not all patients will return the surveys containing this information. However, with good follow-up, response rates should be in the range of 65%–75%. The rate of exacerbations will use medical records data which may not fully reflect patient-reported symptoms; however, it is a very good resource for identifying prescribed medications, ie, oral steroids, which is what we are using to define significant asthma exacerbations.

Summary

Asthma continues to be associated with preventable morbidity and mortality that could be lowered through more consistent delivery of guideline-compliant care in primary care practices. This project uses patient outcomes to test the effectiveness of the Asthma APGAR system and tools developed in collaboration with practicing family physicians and their staff members. The patient asthma APGAR guides collection of the important information required to assess asthma control and the results are linked to action items in the care algorithm. The project uses the available evidence about translating research into practice, including addressing motivation, the process of change, and development of a systemic care process tailored to rural practices. The intervention is simple, requires limited investment of time or money on the part of the practice, and is therefore likely to be feasible for broad dissemination in the future.

Acknowledgments

Funding for this study was provided by the Agency for HealthCare Research and Quality (R01-HS0118431).

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- HedmanLBjergALundbackBRonmarkEConventional epidemiology underestimates the incidence of asthma and wheeze – a longitudinal population-based study among teenagersClin Transl Allergy201221122409857

- AkinbamiLJMoormanJEBaileyCTrends in asthma prevalence, health care use, and mortality in the United States, 2001–2010NCHS Data Brief2012941822617340

- BloomBCohenRAFreemanGSummary health statistics for US children: National Health Interview Survey, 2010Vital Health Stat2011250180

- ManninoDMHomaDMAkiinbamiLJSurveillance for asthma – United States, 1980–1999MMWR CDC Surveill Summ2002511113

- GindeAAEspinolaJACamargoCAImproved overall trends but persistent racial disparities in emergency department visits for acute asthma, 1993–2005J Allergy Clin Immunol2008122231331818538382

- WongGWChowCMChildhood asthma epidemiology: insights from comparative studies of rural and urban populationsPediatr Pulmonol200843210711618092349

- YawnBPWollanPKurlandMJScanlonPA longitudinal study of asthma prevalence in a community population of school age childrenJ Pediatr2002140557658112032525

- YawnBPFryerGEPhillipsRLDoveySMLanierDGreenLAUsing the ecology model to describe the impact of asthma on patterns of health careBMC Pulm Med200551715634351

- NewacheckPWMcManusMFoxHBHungYYHalfonNAccess to health care for children with special health care needsPediatrics20001054 Pt 176076610742317

- LozanoPSullivanSSmithDWeissKThe economic burden of asthma in US children: estimates from the National Medical Expenditure SurveyJ Allergy Clin Immunol1999104595796310550739

- ToTDellSDickPCicuttoLThe burden of illness experienced by young children associated with asthma: a population-based cohort studyJ Asthma2008451454918259995

- RoweBHVoaklanderDCWangDAsthma presentations by adults to emergency departments in Alberta, Canada: a large population-based studyChest20091351576518689586

- SearsMREpidemiology of asthma exacerbationsJ Allergy Clin Immunol2008122466266819014756

- HendersonAJWhat have we learned from prospective cohort studies of asthma in children?Chron Respir Dis20085422523119029234

- FordESManninoDMHomaDMSelf-reported asthma and health-related quality of life: findings from the behavioral and risk factor surveillance systemChest2003123111912712527612

- Savage-BrownAManninoDMReddSCLung disease and asthma severity in adults with asthma: data from the Third National Health and Nutrition ExaminationJ Asthma200542651952316293549

- PappasGHaddenWCKozakLJFisherGFPotentially avoidable hospitalizations: inequalities in rates between US socioeconomic groupsAm J Public Health19978758118169184511

- NationalHeartLung, and Blood InstituteNational Asthma Education and Prevention Expert Panel report 3: guidelines for the diagnosis and management of asthmaBethesda, MDNational Institutes of Health2007 Available from: http://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/guidelines/asthma/method.htmAccessed March 30, 2013

- LundbackBRonmarkELindbergAJonssonACLarssonLGJamesMAsthma control over 3 years in a real-life studyRespir Med2009103334835519042115

- YawnBPApplying the 2007 Expert Panel Report in caring for young children with asthmaJ Clin Outcomes Manage20071412667681

- CabanaMDRandCSBecherOJRubinHRReasons for pediatrician nonadherence to asthma guidelinesArch Pediatr Adolesc Med200115591057106211529809

- SullivanSDLeeTABloughDKA multi-site randomized trial for the effects of physician education and organizational change in chronic asthma care. Cost-effectiveness analysis of the Pediatric Asthma Care Patient Outcomes Research Team II (PAC-PORT II)Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med2005159542843415867115

- PerryTTVargasPAMcCrackenAJonesSMUnderdiagnosed and uncontrolled asthma: findings in rural school children from the Delta region of ArkansasAnn Allergy Asthma Immunol2008101437538118939725

- YawnBPMainousAGIIILoveMMHuestonWDo rural and urban children have comparable asthma care utilization?J Rural Health2001171323911354720

- Hagmolen Of Ten HaveWvan den BergNJvan der PalenJvan AalderenWMBindelsPJLimitations of questioning asthma to assess asthma control in general practiceRespir Med200810281153115818573649

- LevyMLGuideline-defined asthma control: a challenge for primary careEur Respir J200831222923118238943

- BraidoFBaiardiniIStagiEPiroddiMGBalestracciSCanonicaGWUnsatisfactory asthma control: astonishing evidence from general practitioners and respiratory medicine specialistsJ Investig Allergol Clin Immunol2010201912

- LiuAHGilsenanAWStanfordRHLincourtWZiemieckiROrtegaHStatus of asthma control in pediatric primary care: results from the pediatric Asthma Control Characteristics and Prevalence Survey Study (ACCESS)J Pediatr2010157227628120472251

- NortonSPPusicMVTahaFHeathcoteSCarletonBCEffect of a clinical pathway on the hospitalization rates of children with asthma: a prospective studyArch Dis Child2007921606616905562

- FosterJMHoskinsGSmithBLeeAJPriceDPinnockHPractice development plans to acute asthma: randomized controlled trialBMC Fam Pract200782317456241

- RastogiDShettyANeugebauerRHarijithANational Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute guidelines and asthma management practices among inner-city pediatric primary care providersChest2006129361962316537859

- DohertySRJonesPDDavisLRyanNJTreeveVEvidence-based implementation of adult emergency department: a controlled trialEmerg Med Australas2007191313817305658

- YawnBMadisonSBertramSAutomated patient and medication payment method for clinical trialsOpen Access J Clin Trials2012419

- DoboszynskaASwietlikEAsthma management at primary care level: symptoms and treatment of 3305 patients with asthma diagnosed by a family physicianJ Physiol Pharmacol200859Suppl 623124119218647

- VollmerWAssessment of asthma control and severityAnn Allergy Asthma Immunol200493540941315562878

- VollmerWMMarksonLEO’ConnorEFrazierEABergerMBuistASAssociation of asthma control with health care utilization: a prospective evaluationAm J Respir Crit Care Med2002165219519911790654

- NathanRASorknessCAKosinskiMDevelopment of the Asthma Control Test: a survey for assessing asthma controlJ Allergy Clin Immunol20041131596514713908

- SchatzMNakahiroRJonesCHRothRMJoshuaAPetittiDAsthma population management: development and validation of a practical 3-level risk stratification schemeAm J Manag Care2004101253214738184

- JuniperEFAssessing asthma controlCurr Allergy Asthma Rep20077539039417697649

- SchatzMZeigerRSVollmerWMMosenDCookEFDeterminants of future long-term asthma controlJ Allergy Clin Immunol200611851048105317088128

- JuniperEFSvenssonKMorkACStahlEMeasurement properties and interpretation of three shortened versions of the asthma control questionnaireRespir Med200599555355815823451

- SchatzMMosenDMKosinskiMValidity of the Asthma Control Test completed at homeAm J Manag Care2007131266166718069909

- YawnBPBrennemanSKAllen-RameyFCCabanaMDMarksonLEAssessment of asthma severity and asthma control in childrenPediatrics2006118132232916818581

- SkinnerEDietteGAlgatt-BergstromPThe Asthma Therapy Assessment Questionnaire (ATAQ) for children and adolescentsDis Manag20047430531315671787

- PinnockHJuniperEFSheikhAConcordance between supervised and postal administration of the Mini Asthma Quality of Life Questionnaire (MiniAQLQ) and Asthma Control Questionnaire (ACQ) was very highJ Clin Epidemiol20055880981416018916

- CabanaMSlishKNanBLinXClarkNAsking the correct questions to assess asthma symptomsClin Pediatr (Phila)200544431932515864364

- DietteGPatinoCMerrimanBPatient factors that physician use to assign asthma treatmentArch Intern Med2007167131360136617620528

- HermanEJGarbePLMcGeehinMAAssessing community-based approaches to asthma control: the Controlling Asthma in American Cities projectJ Urban Health201188Suppl 11621337047

- RagazziHKellerAEhrensbergerRIraniAMEvaluation of a practice-based intervention to improve the management of pediatric asthmaJ Urban Health201188Suppl 1384821337050

- YawnBPGoodwinMZyzanskiSStangeKTime use during acute and chronic illness visits to a family physicianFam Pract200320447447712876124

- LisspersKStallbergBHasselgrenMJohanssonGSvardsuddKPrimary health care centres with asthma clinics: effects on patients knowledge and asthma controlPrim Care Respir J2010191374419623471

- YawnBBertramSWollanPIntroduction of Asthma APGAR tools improve asthma management in primary care practicesJ Asthma Allergy20081110 Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3121335/Accessed March 29, 201321436980

- JuniperERBousquetJAbetzLBatemanEDIdentifying ‘well-controlled’ and ‘not well-controlled’ asthma using the Asthma Control QuestionnaireRespir Med2006100461662116226443

- YawnBPFactors accounting for asthma variability: achieving optimal symptom control for individual patientsPrim Care Respir J200817313814718264646

- MintzMGilsenanAWBuiCLAssessment of asthma control in primary careCurr Med Res Opin200925102523253119708765

- FriedRAMillerRSGreenLASherrodPNuttingPAThe use of objective measures of asthma severity in primary care: a report from ASPNJ Fam Pract19954121391437636453

- PaceWFagnanLWestDThe Agency for Health Care Research and Quality (AHRQ). Practice-Based Research Network (PBRN) relationship: delivering on a opportunity, challenges, and future directionsJ Am Board Fam Med201124548949221900429

- WestfallJMMoldJFagnanLPractice-based research – “Blue Highways” on the NIH roadmapJAMA2007297440343617244837

- WoolfSHThe meaning of translational research and why it mattersJAMA2008299221121318182604

- SolbergLIBrekkeMLFazioCJLessons from experienced guideline implementers: attend to many factors and use multiple strategiesJt Comm J Qual Improv200026417118810749003

- WinklerprinsVWalsworthDTCoffeyJCClinical Inquiry. How best to diagnose asthma in infants and toddlers?J Fam Pract201160315215421369558

- Rodriguez-MartinezCESossa-BricenoMPCastro-RodriguezJADiscriminative properties of two predictive indices for asthma diagnosis in a sample of preschoolers with recurrent wheezingPediatr Pulmonol201146121175118121626716

- MiravitllesMAndreuIRomeroYSitjarSAltesAAntonEDifficulties in differential diagnosis of COPD and asthma in primary careBr J Gen Pract201262595e68e7522520766

- D’UrzoADMust family physicians use spirometry in managing asthma patients?: NOCan Fam Physician201056212720154240

- KaplanAStanbrookMMust family physicians use spirometry in managing asthma patients?: YESCan Fam Physician201056212620154239

- HoltonCCrockettANelsonMDoes spirometry training in general practice improve quality and outcomes of asthma care?Int J Qual Health Care201123554555321733979

- GlasgowREWagnerEHSchaeferJMahoneyLDReidRJGreeneSMDevelopment and Validation of the Patient Assessment of Chronic Illness Care (PACIC)Med Care200543543644415838407

- JuniperEFEffect of asthma on quality of lifeCan Respir J19985Suppl A77A84A

- JuniperEFNormanGRCoxRMRobertsJNComparison of the standard gamble, rating scale, AQLQ and SF-36 for measuring quality of life in asthmaEur Respir J2001181384411510803

- Agency for Healthcare Research and QualityTranslating Research Into Practice (TRIP)-II. Fact sheet. AHRQ Publication No 01-P017Rockville, MDAgency for Healthcare Research and Quality2001 Available from: http://www.ahrq.gov/research/trip2fac.htmAccessed March 30, 2013

- FarquharCMStryerDSlutskyJTranslating research into practice: the future aheadInt J Qual Health Care2002149323324912108534

- Van BokhovenMAKokGvan der WeijdenTDesigning a quality improvement intervention: a systematic approachQual Saf Health Care200312321522012792013

- GrahamIDLoganJHarrisonMBLost in knowledge translation: time for a map?J Contin Educ Health Prof200626132416557505

- GrimshawJMThomasREMacLennanGEffectiveness and efficiency of guideline dissemination and implementation strategiesHealth Technol Assess200486iiiiv17214960256

- FreemantleNHarveyELWolfFGrimshawJMGrilliRBeroLAPrinted educational materials: effects on professional practice and health care outcomesCochrane Database Syst Rev20002CD00017210796502

- FagnanLDorrDDavisMTurning on the care coordination switch in rural primary care: voices from the practices – clinician champions, clinician partners, administrators, and nurse care managersJ Ambul Care Manage201134330431821673531

- BeroLAGrilliRGrimshawJMHarveyEOxmanADThomsonMAClosing the gap between research and practice: an overview of systematic reviews of interventions to promote the implementation of research findings. The Cochrane Effective Practice and Organization of Care Review GroupBMJ199831771564654689703533