Abstract

Objectives

To evaluate which indirect method for assessing adherence best reflects highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART) effectiveness and the factors related to adherence.

Method

This descriptive, cross-sectional study was performed in 2012 at a reference center of the state of São Paulo. Self-report (simplified medication adherence questionnaire [SMAQ]) and drug refill parameters were compared to the viral load (clinical parameter of the effectiveness of pharmacotherapy [EP]) to evaluate the EP. The “Cuestionario para la Evaluación de la Adhesión al Tratamiento Antiretroviral” (CEAT-VIH) was used to evaluate factors related to adherence and the EP and, complementarily, patient self-perception of adherence was compared to the clinical parameter of the EP.

Results

Seventy-five patients were interviewed, 60 of whom were considered as adherent from the clinical parameter of the EP and ten were considered as adherent from all parameters. Patient self-perception about adherence was the instrument that best reflected the EP when compared to the standardized self-report questionnaire (SMAQ) and drug refill parameter. The level of education and the level of knowledge on HAART were positively correlated to the EP. Forgetfulness, alcohol use, and lack of knowledge about the medications were the factors most frequently reported as a cause of nonadherence.

Conclusion

A new parameter of patient self-perception of adherence, which is a noninvasive, inexpensive instrument, could be applied and assessed as easily as self-report (SMAQ) during monthly drug refill, since it allows monitoring adherence through pharmaceutical assistance. Therefore, patient adherence to HAART could be evaluated using self-perception (CEAT-VIH) and the viral load test.

Introduction

Since its introduction in 1996, the highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART) has decreased the morbidity and mortality due to the acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS).Citation1 However, the maximum effectiveness of the treatment is ensured not only by effective and potent drugs, but also by patient adherence to the therapy.

Poor adherence is a remarkable problem as it increases the chance of virologic failure, decreasing the recovery of CD4 cells, increasing viral load and, therefore, increasing the risk of death. Another important consequence is the increased possibility of mutations resistant to currently available drugs.Citation2

Factors related to poor adherence comprise treatment, health care service, patient, and lifestyle characteristics. Treatment characteristics include inflexible dosing schedules, adverse events, long periods of treatment (over 6 years), and the concomitant use of other drugs in addition to antiretroviral drugs. Among health care service characteristics are the impaired access to health care services, which makes it difficult for the patient to be followed by a health care professional; and smaller services with small staff numbers, which have shown difficulties in standardizing and supervising the performance of health care professionals, as well as promoting technical discussions.Citation3 Forgetfulness, missing medical appointments, demotivation, and the educational level of the patient are also associated with poor adherence. Factors related to the lifestyle are the use of alcohol and injectable drugs, travels, social isolation, depression, and stress, among others.Citation4–Citation8

According to Bartlett,Citation9 an adherence ≥95% is required for viral suppression; however, 40%–60% of patients adhere <90% in Brazil, tending to decrease over time.Citation3 Nevertheless, it has been shown that a moderate adherence (<95%) to more powerful regimens, such as protease inhibitors (PI) and non-nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors, does not significantly affect a decreased viral load,Citation10,Citation11 and the potential to develop mutations is lower in schemes containing PI.Citation2

It is recommended assessing adherence to pharmacotherapy by two methods,Citation12 which may be direct (monitoring plasma concentration of the drug or its metabolites), that tend to be more accurate, but expensive; or indirect (self-reporting through questionnaires, pill counting, drug refill), and cheaper, but require more time to apply and tend to be less accurate. The viral load is one of the most valuable measures for evaluating disease progression and anti-HIV treatment effectiveness.Citation13

Considering that adherence to therapy is an important part of the treatment and that monitoring patient adherence is essential to ensure the maximum effectiveness of the pharmacotherapy, it is important to verify whether the inexpensive methods truly reflect viral suppression and which patient-related factors may influence the effectiveness. Therefore, this study aimed to: 1) evaluate which indirect method for assessing adherence best reflects HAART effectiveness, and 2) which sociodemographic variables and factors are related to adherence and the effectiveness of pharmacotherapy (EP).

Materials and methods

This descriptive, cross-sectional study was conducted in 2012 at the Special Health Care Service of Araraquara, responsible for sexually transmitted infections/AIDS program in the city of Araraquara, Sao Paulo State, Brazil. Patients >18 years who used HAART and had a medical appointment scheduled in the period of the study were included. Patients who died during the study were excluded.

Two indirect methods for assessing adherence to pharmacotherapy were evaluated: drug refill and self-report according to the “simplified medication adherence questionnaire” (SMAQ).Citation14 This SMAQ includes the following questions:

Do you ever forget to take your medications?

Do you always take your medications at the time indicated?

Do you ever stop taking the medication when you feel bad?

Did you forget to take your medication during the weekend?

In the last week, how many times did you not take a dose?

In the last 3 months, how many full days did you not take the medication?

These two methods were compared with the clinical parameter of the EP, defined as a viral load of <400 copies/mL.

To evaluate factors and sociodemographic variables related to adherence and the EP, the Brazilian adapted version of the “Cuestionario para la Evaluación de la Adhesión al Tratamiento Antiretroviral” (CEAT-VIH) was used.Citation15 This questionnaire assesses not only patients’ satisfaction, difficulties, information, and conception about their therapy, but also their self-perception of adherence. Therefore, complementarily, patient self-perception of adherence was also compared to the clinical parameter of the EP.

Data were collected on one individual interview conducted after the patient’s medical appointment. The data collection instrument was a structured form, previously applied to four patients for adequacy, that contained questions including: I – patient characteristics (initials, marital status, sex, date of birth, and education level); II – evaluation of patient adherence to therapy (self-report), according to SMAQ; III – current pharmacotherapy; and IV – evaluation of patient self-perception of adherence, as well as of factors related to poor adherence based on CEAT-VIH.

Viral load data from the last 6 months and drug refill data from the last 3 months were collected using the Drug Logistics Control System (SICLOM).

Patients were considered adherent according to the following parameters:

Viral load (clinical parameter of the EP): the patient had <400 copies/mL or had decreased the viral load by one-third from the last count.Citation16

Self-report parameter using SMAQ: the patient responded negatively to questions 1, 3, and 4, and missed doses less than two times in the last week and <2 complete days in the last 3 months.Citation14

Drug refill parameter: the patient delayed monthly drug refill by not >2 days.Citation16

For statistical analyses, we used the StatPlus® (AnalystSoft, Walnut, CA, USA) and Statistica® (StaSoft Inc., Tulsa, OK, USA) softwares to apply the chi-square test (95% confidence interval), to identify factors and sociodemographic variables that influence pharmacotherapy effectiveness and verify which method for assessing adherence is mostly correlated to the EP. When the expected frequencies were <5, we applied the Yates correction.

The project was approved by the Research Ethics Committee of the Federal University of São Paulo/Hospital São Paulo (No 1365/09). All patients signed an informed consent before participating in this study.

Results

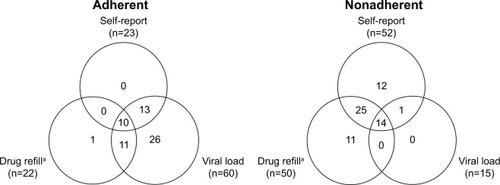

In the period of the study, 455 patients were registered in the service: only 98 of them met the inclusion criteria; 75 (76.5%) of these agreed to participate in the interview and 23 declined their consent. Fourteen of these were considered nonadherent from all parameters, 65 were considered nonadherent from at least one of the parameters and only ten were considered adherent from all parameters (). The sociodemographic characteristics of the patients are described in .

Figure 1 Patients considered adherent and nonadherent to HAART according to SMAQ, drug refill and viral load parameters (N=75).

Abbreviations: HAART, highly active antiretroviral therapy; SMAQ, simplified medication adherence questionnaire.

Table 1 Distribution of patients by sociodemographic variables and correlation with the effectiveness of pharmacotherapy, Araraquara – São Paulo, Brazil, 2010 (N=75)

Patients deemed nonadherent from self-report parameter (52) were asked about the reasons for not taking drugs properly. Forgetfulness (26) and alcohol use (12) were the most frequently reported reasons for nonadherence, followed by the lack of drugs (eight), travels (four), and malaise (four). As strategies to remember to take the medicine, patients reported using alarms, daily pill separators, and caregivers’ support.

From the responses to CEAT-VIH questionnaire, it was found that most patients believed having less or sufficient information about their drugs and properly following treatment requires a lot of effort (). As for self-perception according to CEAT-VIH, 58 patients considered themselves as fairly adherent, which strongly corresponds to the number of patients deemed adherent from the clinical parameter of the EP (viral load) (); on the other hand, less than half were considered adherent from self-report (SMAQ) and drug refill parameters, compared to the clinical parameter.

Table 2 Analysis of factors that possibly influence adherence and correlation with the effectiveness of pharmacotherapy, Araraquara, Sao Paulo State, Brazil, 2010 (N=75)

As difficulties to adhere to treatment, patients reported the complexity of the pharmacotherapy, drug size, drug taste, the amount of drugs, and the dosing schedule.

The association between factors or sociodemographic variables and the EP was statistically tested, and only the level of education (P=0.003) and the information that the patient believes to have about HAART (P=0.009) showed to be correlated. The therapeutic regimen (P=0.994) and the number of tablets administered daily (P=0.282) did not show any statistically significant relationship with the EP ().

Discussion

Though indirect methods for assessing adherence are recommended for controlling and evaluating adherence to HAART by the sexually transmitted infections/AIDS programs of Pharmaceutical Assistance,Citation17 our data showed that there were differences in results depending on the instrument used ().

Among the indirect methods used in this study, the viral load is the method that best reflects the EP.Citation13,Citation17 Nevertheless, it is more invasive and expensive, requires laboratory exams, and should be performed at least twice a year according to guidelines.Citation17

It is recommended to use two methods for assessing the effectiveness of pharmacotherapy.Citation12 The first method could be the viral load, which is the most effective for evaluating the EP. The second method should be as efficient as the viral load and allow evaluation of adherence in an inexpensive, easy-to-apply, less invasive way; it should also allow to be applied with a higher frequency, for example during monthly drug refill. This second method could be the self-report using SMAQ or drug refill.

However, the self-report parameter has been shown to be too strict, since, according to Shuter et alCitation10 and Bangsberg,Citation11 an adherence of <95% may not have a significant impact on the viral load when potent regimens, such as PI and non-nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors, are used. Only one patient in our study did not use one of these regimens. Therefore, this method may be excessively rigorous for detecting nonadherence to HAART.

Drug refill parameter also underestimated the EP, probably because it was equally stringent. This parameter considers that a delay of >2 days in monthly drug refill already reflects nonadherence; however, the time to refill depends on the amount of dispensed units and also on the days of operation of the service. Furthermore, the lack of policies and incentives for drug fractionation prevents this method from being effective and to directly reflect adherence.Citation18

On the other hand, patient self-perception, evaluated using CEAT-VIH, was the instrument that best reflected the EP when compared to drug refill and self-report (SMAQ) parameters. Differently from self-report, patient self-perception does not depend on a quantitative memory, but on a qualitative memory: patients classify how adherent they believe they are without needing to remember specific events, which may become a more precise assessment parameter.Citation15

Besides, CEAT-VIH not only allows patients to evaluate and rethink about their adherence, but also allows health care professionals to identify other factors possibly related to poor adherence, such as drug-related problems and adverse events.Citation15 This way, health care professionals become capable of proposing interventions even before investigating the EP by clinical parameters. Evaluating adherence is important since asymptomatic patients do not believe in the risk of nonadherence and tend to take their medication less regularly.Citation19

Although monitoring adherence by patient self-perception may be time-consuming, as it depends on interviews and patient availability, it may be performed during the health counseling by multidisciplinary teams. Health counseling, an interactive, two-way process that starts from patient EP and allows identifying the reasons for nonadherence, can improve patient knowledge about the therapy and the consequences of nonadherence; therefore, the patient will be more willing to adhere.Citation19,Citation20

In our study, a correlation between EP and the level of education was observed. Previous studies confirmed the relationship between literacy and adherence,Citation21,Citation22 and demonstrated that more educated patients have a higher chance to reach viral suppression than those with no or low literacy. This is because subjects with low literacy may have difficulties in understanding the guidance provided by health care professionals and, therefore, will not sufficiently adhere to treatment.Citation23 Health literacy indicates the ability with which patients receive, process, and understand information necessary to their treatment. HIV+ patients with low health literacy generally present with low knowledge and understanding about their health condition, lower perception about the treatment, low adherence to medications and decreased immune function, and tend to be three times less adherent than those with more knowledge and understanding about HAART.Citation24,Citation25

Therefore, data on this study suggest that a new parameter of patient self-perception of adherence to pharmacotherapy, a noninvasive, cheap instrument, could be applied and assessed as easily as the self-report (SMAQ) parameter during monthly drug refill. This way, it allows monitoring adherence through pharmaceutical assistance, even before medical visits and routine laboratory tests, and making interventions in order to improve adherence.

As observed in the systematic review and meta-analysis of Conn et al,Citation26 interventions to improve adherence increase significantly patient knowledge about medications, which improves their quality of life, physical ability, and symptoms. Other interventions, such as treatment simplification, also have a positive impact on morbidity and reduce treatment costs with human resources, since professionals are efficiently allocated.Citation27 Analyses on the economic impact of the interventions to improve adherence also showed a significant decrease in costs for medical appointments and hospitalizations, though this aspect still needs further investigation.Citation28,Citation29

Concerning factors related to nonadherence, in our study, the reasons mainly reported in CEAT-VIH were the need of much effort to comply with the pharmacotherapy and the lack of knowledge about medications, which showed a significant correlation with the parameter of EP. Also, according to the responses to SMAQ, the mostly reported reason was forgetfulness.

These factors are probably related: a penta-continental study carried out by Nachega et alCitation23 showed that 43% of patients admit to have forgotten at least one dose in the last month, suggesting that they possibly do not completely understand the impact of forgetting to take medications on their health. It shows that the lack of information regarding the risks of not using the medications prescribed can cause nonadherence and corroborates the results of our study. Educational interventions and pharmacotherapy management could also contribute to solve this problem.Citation26

Conclusion

The EP was best reflected by the patient’s self-perception, when compared to the standardized self-report questionnaire (SMAQ) and drug refill.

The level of education and of knowledge on HAART reported by the patient are positively correlated to the EP.

Most patients feel very satisfied and capable of following treatment, although they reported making a great effort to follow treatment properly, and recognize the benefits HAART can bring to their health and the improvements they have after beginning the therapy.

Author contributions

All authors made substantial contributions to conception and design, acquisition of data, or analysis and interpretation of data; took part in drafting the article or revising it critically for important intellectual content; gave final approval of the version to be published; and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the multidisciplinary team of the Special Service of Araraquara for collaborating and enabling this study; the financial support provided by the Program of Support to Scientific Development of the School of Pharmaceutical Sciences at the Universidade Estadual Paulista – UNESP (process no 2010/21-I); Ruth Ferreira Santos-Galduróz, for helping in the statistical analysis; and Thaís de Souza Cordeiro, for her support in the study. The authors would also like to thank FAPESP for the financial support in this project, under the grant #2014/03468-6, São Paulo Research Foundation (FAPESP).

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- CardosoSWTorresTSSantini-OliveiraMMarinsLMSVelosoVGGrinsztejnBAging with HIV: a practical reviewBrazilian J Infect Dis2013174464479

- von WylVKlimkaitTYerlySSwiss HIV Cohort StudyAdherence as a predictor of the development of class-specific resistance mutations: the Swiss HIV Cohort StudyPLoS One2013810e7769124147057

- NemesMICastanheiraERHelenaETAdesão ao tratamento, acesso e qualidade da assistência em Aids no Brasil [Treatment adherence, access and AIDS assistance quality in Brazil]Rev Assoc Med Bras2009552207212 Portuguese19488660

- NemesMIBCarvalhoHBSouzaMFMAntiretroviral therapy adherence in BrazilAIDS200418Suppl 3S15S2015322479

- Cantudo-CuencaMRJiménez-GalánRAlmeida-GonzálezCVMorillo-VerdugoRConcurrent use of comedications reduces adherence to antiretroviral therapy among HIV-infected patientsJ Manag Care Spec Pharm201420884485025062078

- TsegaBSrikanthBAShewameneZDeterminants of non-adherence to antiretroviral therapy in adult hospitalized patients, Northwest EthiopiaPatient Prefer Adherence2015937338025784793

- AnkrahDNKosterESMantel-TeeuwisseAKArhinfulDKAgyepongIALarteyMFacilitators and barriers to antiretroviral therapy adherence among adolescents in GhanaPatient Prefer Adherence20161032933727042024

- GuimarãesMDCRochaGMCamposLNDifficulties reported by HIV-infected patients using antiretroviral therapy in BrazilClin (São Paulo)2008632165172

- BartlettJAAddressing the challenges of adherenceJ Acquir Immune Defic Syndr200229Suppl 1S2S1011832696

- ShuterJSarloJAKanmazTJRodeRAZingmanBSHIV-infected patients receiving lopinavir/ritonavir-based antiretroviral therapy achieve high rates of virologic suppression despite adherence rates less than 95%J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr20074514817460469

- BangsbergDRLess than 95% adherence to nonnucleoside reverse-transcriptase inhibitor therapy can lead to viral suppressionClin Infect Dis200643793994116941380

- PolejackLSeidlEMFMonitoramento e avaliação da adesão ao tratamento antirretroviral para HIV/AIDS: desafios e possibilidades [Monitoring and evaluation of adherence to ARV treatment for HIV/AIDS: challenges and possibilities]Cien Saude Colet201015Suppl 112011208 Portuguese20640279

- VajpayeeMMohanTCurrent practices in laboratory monitoring of HIV infectionIndian J Med Res2011134680182222310815

- KnobelHAlonsoJCasadoJLGEEMA Study GroupValidation of a simplified medication adherence questionnaire in a large cohort of HIV-infected patients: the GEEMA StudyAIDS200216460561311873004

- RemorEMilner-MoskovicsJPreusslerGAdaptação brasileira do Cuestionario para la Evaluación de la Adhesión al Tratamiento Antiretroviral [Brazilian adaptation of the Assessment of Adherence to Antiretroviral Therapy Questionnaire]Rev Saude Publica2007415685694 Portuguese17713708

- BRASIL. Ministério da SaúdeSecretaria de Vigilância em Saúde. Departamento de DST AIDS e Hepatites ViraisAdesão ao tratamento antirretroviral no Brasil: coletânea de estudos do projeto ATAR: projeto ATAR (série b. Textos básicos de saúde) [Adherence to antiretroviral treatment in Brazil: study collection of the ATAR project: ATAR project]Ministério da Saúde2010408

- BRASIL. Ministério da Saúde. Secretaria de Vigilância em Saúde. Departamento de DST AIDS e Hepatites ViraisProtocolo clínico e Diretrizes Terapêuticas para Manejo da Infecção pelo HIV em Adultos [Clinical protocol and therapeutic guidelines for managing HIV infection in adults] InternetBrasília (DF)Ministério da Saúde20155357 Available from: http://www.aids.gov.br/sites/default/files/anexos/publicacao/2013/55308/protocolofinal_31_7_2015_pdf_31327.pdfAccessed April 18, 2016

- MastroianniPDCLucchettaRCSarraJDRGaldurózJCFEstoque doméstico e uso de medicamentos em uma população cadastrada na estratégia saúde da família no Brasil [Household storage and use of medications in a population served by the family health strategy in Brazil]Rev Panam Salud Pública2011295358364 Portuguese21709941

- GaoXNauDPRosenbluthSAScottVWoodwardCThe relationship of disease severity, health beliefs and medication adherence among HIV patientsAIDS Care200012438739811091771

- KalichmanSCBenotschESuarezTCatzSMillerJRompaDHealth literacy and health-related knowledge among persons living with HIV/AIDSAm J Prev Med200018432533110788736

- ColombriniMRCLopesMHBDMde FigueiredoRMAdesão à terapia antiretroviral para HIV/AIDS [Adherence to the antiretroviral therapy for HIV/AIDS]Rev Esc Enferm USP2006404576581 Portuguese17310576

- SeidlEMFTróccoliBTDesenvolvimento de escala para avaliação do suporte social em HIV/aids [Development of a scale for evaluating the social support in HIV/AIDS]Psicol Teor e Pesqui2006223317326

- NachegaJBMorroniCZunigaJMHIV treatment adherence, patient health literacy, and health care provider-patient communication: results from the 2010 AIDS Treatment for Life International SurveyJ Int Assoc Physicians AIDS Care (Chic)201211212813322361449

- WolfMSDavisTCOsbornCYSkripkauskasSBennettCLMakoulGLiteracy, self-efficacy, and HIV medication adherencePatient Educ Couns200765225326017118617

- MastroianniPCMachucaMLa pedagogía de la autonomía para optimizar los resultados del tratamiento farmacéutico [Teaching autonomy in order to optimize drug therapy outcomes]Rev Panam Salud Publica2012325389390 Spanish

- ConnVSRupparTMEnriquezMCooperPSPatient-centered outcomes of medication adherence interventions: systematic review and meta-analysisValue Heal2016192277285

- NachegaJBMugaveroMJZeierMVitóriaMGallantJETreatment simplification in HIV-infected adults as a strategy to prevent toxicity, improve adherence, quality of life and decrease healthcare costsPatient Prefer Adherence2011535736721845035

- SaberiPDongBJJohnsonMOGreenblattRMCocohobaJMThe impact of HIV clinical pharmacists on HIV treatment outcomes: a systematic reviewPatient Prefer Adherence2012629732222536064

- CarnevaleRCde Godoi Rezende Costa MolinoCVisacriMBMazzolaPGMorielPCost analysis of pharmaceutical care provided to HIV-infected patients: an ambispective controlled studyDaru20152311325889580