Abstract

Background

A substantial aspect of health literacy is the knowledge of prescribed medication. In chronic heart failure, incomplete intake of prescribed drugs (medication non-adherence) is inversely associated with clinical prognosis. Therefore, we assessed medication knowledge in a cohort of patients with decompensated heart failure at hospital admission and after discharge in a prospective, cross-sectional study.

Methods

One hundred and eleven patients presenting at the emergency department with acute decompensated heart failure were included (mean age 78.4±9.2, 59% men) in the study. Patients’ medication knowledge was assessed during individual interviews at baseline, course of hospitalization, and 3 months after discharge. Individual responses were compared with the medical records of the referring general practitioner.

Results

Median N-terminal prohormone of brain natriuretic peptide plasma concentration in the overall population at baseline was 4,208 pg/mL (2,023–7,101 pg/mL [interquartile range]), 20 patients died between the second and third interview. The number of prescribed drugs increased from 8±3 at baseline to 9±3 after 3 months. The majority of patients did not know the correct number of their drugs. Medication knowledge decreased continuously from baseline to the third interview. At baseline, 37% (n=41) of patients stated the correct number of drugs to be taken, whereas only 18% (n=16) knew the correct number 3 months after discharge (P=0.008). Knowledge was inversely related to N-terminal prohormone of brain natriuretic peptide levels.

Conclusion

Medication knowledge of patients with acute decompensated heart failure is poor. Despite care in a university hospital, patients’ individual medication knowledge decreased after discharge. The study reveals an urgent need for better strategies to improve and promote the knowledge of prescribed medication in these very high-risk patients.

Introduction

Chronic heart failure (CHF) is a serious health care problem affecting 1%–2% of the adult population in developed countries with the prevalence rising to ≥10% among persons ≥70 years of age.Citation1 Evidence-based pharmacotherapy has improved prognosis in patients with systolic heart failure.Citation2 Adherence to these medications, defined as the extent to which patients take medications as prescribed, prevents hospitalization and mortality.Citation3,Citation4

Management of chronic diseases, including heart failure, requires a high level of self-care skills that are determined by patients’ health literacy, which is defined as the degree to which patients have the capacity to adapt health information and services needed to make appropriate health decisions.Citation4 A substantial aspect of health literacy represents the knowledge of one’s medical condition and treatment regimens, especially daily medication.Citation5 Medication knowledge was shown to determine medication adherence in CHF patients and is inversely associated with outcomes in CHF.Citation6,Citation7 Lack of patients’ knowledge about their discharge medication increases the risk of drug-related problems.Citation4 During hospitalization, established medication regimens are frequently modified, and in >75% of cases, even three or more alterations are carried out.Citation8 A fact that represents a challenge for the interaction between health care providers and patients.

Cognitive functioning is impaired in patients with decompensated heart failure. It improves but does not normalize after recompensation Citation9,Citation10 Several studies characterized health literacy and medication knowledge in CHF populations either at the time of hospitalization or after discharge. However, a potential alteration of knowledge over time from acute hospital admission to the outpatient setting and a potential role of recompensation as an effector of knowledge have not been investigated. We hypothesized an increase in the individual medication-related knowledge during the course of treatment. Therefore, the objective of the present study was to quantify medication knowledge in a cohort of patients referred to and discharged from a tertiary clinical center due to decompensated heart failure.

Methods

Patients

This evaluation is a prospective, cross-sectional study. We consecutively enrolled 111 patients between 54 and 98 years of age who had been hospitalized for decompensated heart failure at the emergency department of the Saarland University Hospital. The following inclusion criteria were required: acute decompensated heart failure, established medical therapy, and an ability to give written consent and participate in the interview. CHF was defined according to the European Society of Cardiology guidelines.Citation2 After written informed consent was obtained, the patients were interviewed by an independent data collector not involved in patient care. The study was approved by the local ethics committee (“Ethik-Kommission der Ärztekammer des Saarlandes”) (identification number 98/13) in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. All patients gave their written informed consent to participate in the study.

Clinical and demographic variables

Demographic characteristics (sex, age), body mass index, marital status, degree of education, New York Heart Association functional class for dyspnea, cardiovascular (CV) comorbidities, and admitting diagnosis were assessed (). Heart rate and blood pressure were measured at baseline after resting for at least 5 minutes. N-terminal prohormone of brain natriuretic peptide (NT-proBNP) levels were measured at baseline. The number and type (CV and non-CV) of medicines prescribed were documented and verified from the patient chart at admission (baseline = interview 1) and during hospitalization at days 2–4 (second interview). At home, 3 months (mean 106 days) after discharge, the prescribed medication was verified by comparison with the outpatient record of the treating general practitioner.

Table 1 Baseline characteristics of the study population (N=111)

Patient-reported medication knowledge

Fifteen types of prescribed CHF-related drugs were categorized (). To determine patients’ knowledge about their medication, the following questions were asked: How many different medications do you take? How many heart-specific medications do you take? Do you know the name (generic or brand)? Do you know the function/mode of action? Do you know the dosage form? Do you know when to take the medications? The patients were asked these questions at the time of hospitalization in the emergency department (baseline), in the hospital ward after stabilization on days 2–4 (second interview) and at home, 3 months after discharge (third interview). Knowledge at baseline and at the second interview refers to the medication taken before hospitalization. Knowledge at the third interview refers to medication taken according to the general practitioner’s record in the outpatient setting.

Table 2 Knowledge of prescribed HF-related drug classes (n: patient knew drug type)

Statistics

This evaluation is a descriptive, cross-sectional study. Data are presented as mean ± standard deviation (SD) of the mean and their distribution as percentages unless otherwise specified. Baseline characteristics were presented using descriptive statistics with mean (SD) for quantitative variables, and numbers and percentages for categorical variables. Significance tests were repeated-measures analysis of variance using within-subjects factor group (hospital admission, hospital stay, and 3-month follow-up) including post hoc Bonferroni tests to assess individual differences with respect to medication knowledge. Values of P<0.05 were considered significant. All statistical analyses were calculated using IBM SPSS statistics software (version 23.0; IBM Corporation, Armonk, NY, USA).

Results

Patients

The baseline characteristics of the 111 patients included in the study are summarized in . The mean age was 78.4±9.2 years, 59% were males, body mass index 29.1±5.8 kg/m2, 56% were married/in relationship. On average, patients were categorized as New York Heart Association class III prior to hospitalization. Mean heart rate at hospital admission was 83±22 bpm. Mean systolic blood pressure was 137±25 mmHg. Median NT-proBNP plasma concentration in the overall population at baseline was 4,208 pg/mL (2,023–7,101 pg/mL [interquartile range]). The most common comorbidities were arterial hypertension (52%), coronary heart disease (50%), atrial fibrillation (47%), chronic kidney disease (36%), diabetes mellitus (29%), and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (10%). Of the 111 patients included in the study, 20 died between the second and third interview.

Number and types of prescribed drugs

At baseline, the patients took, on average, 4±2 prescribed drugs out of the 15 CV drug classes (). The average number of totally prescribed drugs was 8±3 per person. After 3 months, each patient took 5±1 prescribed drugs out of the 15 CV drug classes (totally number of daily medications was 9±3 per person). Hence, the number of drugs to be taken increased by an average of one per person due to additional prescription during hospitalization. Of the different drug classes, oral anticoagulation (OAC)/VKA (phenprocoumon) and aspirin were the best known ().

Knowledge of the number of daily medications

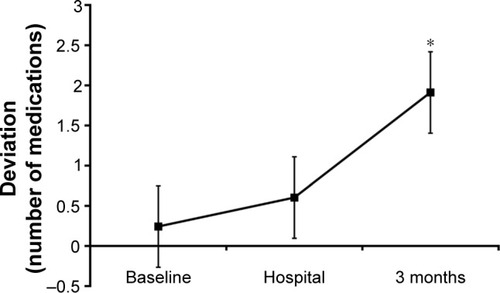

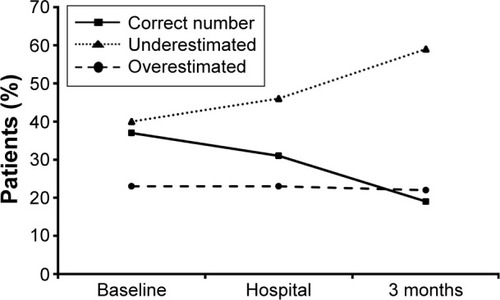

To assess the knowledge of the number of drugs taken, the number stated by the patient was compared to the prescribed number and calculated as percent deviation. Knowledge of the correct number of daily medications assessed at baseline and at home, 3 months after discharge is shown in .

Figure 1 (A) Patients’ knowledge of the number of drugs compared to approved number of prescribed drugs at home (baseline). Each line indicates one patient (n=111). (B) Patients’ knowledge of the number of drugs compared to approved number of prescribed drugs at home (3 months). Each line indicates one patient (n=91). 0% deviation = correct number of drugs stated.

In contrast to our expectation, medication knowledge decreased continuously from baseline to the third interview. At baseline, 41 patients (37%) stated the correct number of drugs taken, whereas only 16 patients (18%) knew the correct number after discharge (P=0.008). shows that the number of patients underestimating the number of drugs particularly increased after discharge. The number of patients exhibiting a deviation of 100% increased from six patients at baseline to 14 patients at the third interview. illustrates the amount of underestimation of the correct number of medications.

Knowledge of the number of daily medications based on NT-proBNP levels and age

To assess individual knowledge of heart-specific medication (correct number, name [generic or brand] out of the 15 CV drug classes, mode of action, dosage form, time-points of administration) in relation to the severity of heart failure and age, patients were stratified according to NT-proBNP and age tertiles. An inverse relation between medication knowledge and NT-proBNP levels was found at all three interviews (time-points) as percent knowledge of the correct number of drugs decreased from tertile 1 to tertile 3 (). Patients within the second age tertile (76–82 years) exhibited the best knowledge compared to older or younger individuals ().

Figure 4 Medication knowledge depending on NT-proBNP level tertiles at the time of hospitalization (baseline). Percent of correct answers (correct number, name [generic or brand], mode of action, dosage form, time-points of administration) at baseline (n=111), at days 2–4 of hospital stay (n=106), and 3 months after discharge from the hospital (n=91) of surviving patients based on NTproBNP values at baseline. Median ± SE.

![Figure 4 Medication knowledge depending on NT-proBNP level tertiles at the time of hospitalization (baseline). Percent of correct answers (correct number, name [generic or brand], mode of action, dosage form, time-points of administration) at baseline (n=111), at days 2–4 of hospital stay (n=106), and 3 months after discharge from the hospital (n=91) of surviving patients based on NTproBNP values at baseline. Median ± SE.](/cms/asset/a1e8875b-9345-4a9f-bd07-186d77344dec/dppa_a_113912_f0004_b.jpg)

Figure 5 Medication knowledge depending on age tertiles. Percent of correct answers (correct number, name [generic or brand], mode of action, dosage form, time-points of administration) at baseline (n=111), at days 2–4 of hospital stay (n=106), and 3 months after discharge from the hospital (n=91) of surviving patients based on age tertiles. Median ± SE.

![Figure 5 Medication knowledge depending on age tertiles. Percent of correct answers (correct number, name [generic or brand], mode of action, dosage form, time-points of administration) at baseline (n=111), at days 2–4 of hospital stay (n=106), and 3 months after discharge from the hospital (n=91) of surviving patients based on age tertiles. Median ± SE.](/cms/asset/b9529b62-db07-411f-b356-72386d16d860/dppa_a_113912_f0005_b.jpg)

Discussion

The main finding of this study was that the individual level of knowledge regarding heart failure-related medication was low in a cohort of CHF patients hospitalized for decompensated heart failure and was inversely related to the severity of the disease but not with regard to age. In contrast to our expectations, the knowledge decreased even further from the time of hospital admission to the outpatient setting.

CHF is one of the most important causes of morbidity and mortality in Western countries, and symptoms related to CHF are the leading cause of hospitalization,Citation11,Citation12 contributing to 70% of the total treatment-related costs in patients aged >65 years, representing ~2% of the total health-care expenditure in industrialized countries.Citation13 Patients with CHF require polypharmacy to control symptoms, slow disease progression, and decrease hospitalization and mortality.Citation2 Health literacy, self-care skills, and, in particular, knowledge of one’s medication are a prerequisite for sustained medication adherence. Low literacy is associated with adverse outcomes in heart failure, including increased risk of hospitalization.Citation4

Hospitalization for heart failure is closely and inversely linked to outcome in patients with chronic heart failure.Citation14 An important predictor of rehospitalization among other patient-related factors is medication non-adherence, which may account for up to one-third of hospitalizations.Citation15

In our cohort, medication knowledge was lower than expected. Data from previous studies are heterogeneous and not easily comparable due to differences of the design and methodology. In a Swedish study population of elderly CHF patients, 55% could correctly name what medication had been prescribed 1 month after prescription.Citation16 In a population of patients discharged from an internal medicine residency service at a community-based teaching hospital, 86% were aware that they had been prescribed new medicines, but fewer could correctly identify the name (64%) or number (74%) of new drugs in an interview between 4 and 18 days after discharge.Citation17 Interestingly in our study, a lack of knowledge was not related to older age, a finding that is indirectly supported by a recent literature review, suggesting that older age alone is not related to poorer medication adherence in patients with CHF.Citation18

Reasons for low health literacy and lack of knowledge are multifactorial and may even be a proxy for other determinants such as cognitive impairment, severity of disease, socioeconomic characteristics, and other barriers to sufficient health care that are associated with poor outcomes.Citation4 Apart from such patient-related factors, other factors related to health care providers (eg, communication strategies) are crucial and determine patients’ knowledge.

Patients in our study received standardized advice regarding the type, dosage, and purpose of discharge medication by the attending physician at the time of discharge. During the outpatient course, follow-up visits were provided by office-based cardiologists and general practitioners pursuing individual counseling strategies. Thus, the knowledge deficits observed may result from a lack of an educational strategy implemented in the clinical routine. Though the role for patient counseling and education seems obvious, health care providers tend to lose focus and – maybe even more important – are often unaware of literacy problems or overestimate patients’ understanding of health information and knowledge. Thus, appropriate strategies beyond standard instructions are not implemented.Citation4

A variety of strategies and interventions focusing on education to promote patients’ health literacy and knowledge can be found in the literature and are highlighted by the current heart failure guidelines and consensus documents.Citation2,Citation4 Education was shown to improve knowledge, self-monitoring, medication adherence, time to hospitalization, and reduced days spent in the hospital.Citation19 Patients who receive structured in-hospital education have higher knowledge scores at discharge and 1 year later when compared with those who did not receive in-hospital education.Citation20 Among the strategies to improve recall of medical advice, complementing verbal information with written instructions improved medication recall in a broad spectrum of patient populations.Citation21–Citation23 Implementation of an enhanced medication plan as an adjunct to the discharge conversation between physician and patient improved information transfer and patients’ knowledge of their drug treatment in a cohort of patients from several internal clinics in a university hospital. Interestingly, the intervention did not prolong the overall discharge process.Citation21 Although, to date, a clear survival benefit of in-hospital or discharge education could not be demonstrated, prior data have suggested that discharge education may result in fewer days of hospitalization, lower costs, and lower mortality rates within a 6-month follow-up.Citation24

Previous studies in CHF patients like CogImpair-HF documented changes in cognitive function, which improved after recompensation.Citation9 In contrast, in our study, individual medication knowledge decreased over time. This may be due to differences in the study design. In the CogImpair-HF study, patients where reevaluated after successful recompensation 14±7 days after the index evaluation. In our study, patients were questioned on days 2–4 and after 3 months. At least, the time of the latter interview might have been postponed too far from the index event, leaving room for potential renewed decompensation and associated gaps of knowledge. On the other hand, the repeated interview itself may confer a training effect; however, this was clearly not sufficient to improve medication knowledge.

There are some limitations of this investigation. One is the relatively small sample size, which may not be regarded as representative of the overall heart failure population. Future studies with appropriate sample sizes are needed to confirm our study results. Another point is that we did not assess potential and clinically relevant cognitive disorders (eg, depression and dementia) before inclusion. Such disorders are highly prevalent in heart failure and play a central role for patient-related adherence.Citation25 Therefore, we cannot rule out completely that cognitive impairments associated with cardiac decompensation may have been confounded with symptoms of neurocognitive disorders. Due to structural limitations, it was not feasible to apply dedicated cognitive tests to measure the complete range of cognitive functions in our study. This point should be addressed by dedicated research protocols in future studies.

Conclusion and implications

In this observational study, we documented a low level of medication-associated knowledge in a contemporary cohort of CHF patients. In contrast to our hypothesis, knowledge decreased over time despite hospital care. The main reason for these findings may be found in the absence of structured counseling during hospitalization at discharge and during ambulatory care. Therefore, a central necessity is the recognition of the individual extent of patients’ health literacy and to identify patients at risk for low literacy, which may affect and compromise even basic skills. Moreover, this study underpins the need for focused patient counseling during hospitalization, at discharge, and within the outpatient setting regarding seamless pharmacotherapy in CHF patients. In order to reliably continue these therapies after discharge, continuous and structured communication between clinicians, primary care physicians, and patients is essential. Additional and innovative strategies addressing medicine management in this high-risk population are urgently needed.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- MosterdAHoesAWClinical epidemiology of heart failureHeart20079391137114617699180

- McMurrayJJAdamopoulosSAnkerSDESC Committee for Practice GuidelinesESC Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure 2012: The Task Force for the Diagnosis and Treatment of Acute and Chronic Heart Failure 2012 of the European Society of Cardiology. Developed in collaboration with the Heart Failure Association (HFA) of the ESCEur Heart J201233141787184722611136

- FitzgeraldAAPowersJDHoPMImpact of medication nonadherence on hospitalizations and mortality in heart failureJ Card Fail201117866466921807328

- EvangelistaLSRasmussonKDLarameeASHealth literacy and the patient with heart failure – implications for patient care and research: a consensus statement of the Heart Failure Society of AmericaJ Card Fail201016191620123313

- LaufsURettig-EwenVBöhmMStrategies to improve drug adherenceEur Heart J201132326426820729544

- van der WalMHJaarsmaTMoserDKVeegerNJvan GilstWHvan VeldhuisenDJCompliance in heart failure patients: the importance of knowledge and beliefsEur Heart J200627443444016230302

- HopeCJWuJTuWYoungJMurrayMDAssociation of medication adherence, knowledge, and skills with emergency department visits by adults 50 years or older with congestive heart failureAm J Health Syst Pharm200461192043204915509127

- HimmelWKochenMMSornsUHummers-PradierEDrug changes at the interface between primary and secondary careInt J Clin Pharmacol Ther200442210310915180171

- KindermannIFischerDKarbachJCognitive function in patients with decompensated heart failure: the cognitive Impairment in Heart Failure (Cogimpair-HF) studyEur J Heart Fail201214440441322431406

- FikenzerKKnollALenskiDSchulzMBöhmMLaufsUChronische Herzinsuffizienz: Teufelskreis aus geringer Einnahmetreue von Medikamenten und kardialer Dekompensation [Poor medication adherence and worsening of heart failure – a vicious circle]Dtsch Med Wochenschr20141394723902394 German25390627

- ZannadFAgrinierNAllaFHeart failure burden and therapyEuropace200911Suppl 5v1v919861384

- AllaFZannadFFilippatosGEpidemiology of acute heart failure syndromesHeart Fail Rev2007122919517450426

- StewartSMacIntyreKCapewellSMcMurrayJJHeart failure and the aging population: an increasing burden in the 21st century?Heart2003891495312482791

- GheorghiadeMVaduganathanMFonarowGCBonowRORehospitalization for heart failure: problems and perspectivesJ Am Coll Cardiol201361439140323219302

- Van der WalMHLJaarsmaTvan VeldhuisenDJNon-compliance in patients with heart failure: how can we manage it?Eur J Heart Fail20057151715642526

- ClineCMBjorck-LinneAKIsraelssonBYWillenheimerRBErhardtLRNon-compliance and knowledge of prescribed medication in elderly patients with heart failureEur J Heart Fail19991214514910937924

- ManiaciMLHeckmanMGDawsonNLFunctional health literacy and understanding of medications at dischargeMayo Clin Proc200883555455818452685

- KruegerKBotermannLSchorrSGGriese-MammenNLaufsUSchulzMAge-related medication adherence in patients with chronic heart failure: a systematic literature reviewInt J Cardiol201518472873525795085

- BorenSAWakefieldBJGunlockTLWakefieldDSHeart failure self-management education: a systematic review of the evidenceInt J Evid Based Healthc2009715916821631856

- Gwadry-SridharFHArnoldJMZhangYBrownJEMarchioriGGuyattGPilot study to determine the impact of a multidisciplinary educational intervention in patients hospitalized with heart failureAm Heart J2005150598216290975

- SendAFSchwabMGaussARudofskyGHaefeliWESeidlingHMPilot study to assess the influence of an enhanced medication plan on patient knowledge at hospital dischargeEur J Clin Pharmacol201470101243125025070189

- WatsonPWMcKinstryBA systematic review of interventions to improve recall of medical advice in healthcare consultationsJ R Soc Med2009102623524319531618

- KharodBVJohnsonPBNestiHARheeDJEffect of written instructions on accuracy of self-reporting medication regimen in glaucoma patientsJ Glaucoma200615324424716778648

- KoellingTMJohnsonMLCodyRJAaronsonKDDischarge education improves clinical outcomes in patients with chronic heart failureCirculation2005111217918515642765

- FanHYuWZhangQDepression after heart failure and risk of cardiovascular and all-cause mortality: a meta-analysisPrev Med201463364224632228