Abstract

Objective

To assess quality of life and satisfaction regarding immunoglobulin-replacement therapy (IgRT) treatment according to the route (intravenous Ig [IVIg] or subcutaneous Ig [SCIg]) and place of administration (home-based IgRT or hospital-based IgRT).

Subjects and methods

Children 5–15 years old treated for primary immunodeficiency disease (PIDD) with IgRT for ≥3 months were included in a prospective, noninterventional cohort study and followed over 12 months. Quality of life was assessed with the Child Health Questionnaire – parent form (CHQ-PF)-50 questionnaire. Satisfaction with IgRT was measured with a three-dimensional scale (Life Quality Index [LQI] with three components: factor I [FI], treatment interference; FII, therapy-related problems; FIII, therapy settings).

Results

A total of 44 children (9.7±3.2 years old) receiving IgRT for a mean of 5.6±4.5 years (median 4.1 years) entered the study: 18 (40.9%) were receiving hospital-based IVIg, two (4.6%) were receiving home-based IVIg, and 24 (54.6%) were treated by home-based SCIg. LQI FIII was higher for home-based SCIg than for hospital-based IVIg (P=0.0003), but there was no difference for LQI FI or LQI FII. LQI FIII significantly improved in five patients who switched from IVIg to SCIg during the follow-up when compared to patients who pursued the same regimen (either IVIg or SCIg). No difference was found on CHQ-PF50 subscales, LQI FI, or LQI FII.

Conclusion

Home-based SCIg gave higher satisfaction regarding therapy settings than hospital-based IVIg. No difference was found on other subscales of the LQI or CHQ-PF50 between hospital-based IVIG and home-based SCIG.

Introduction

Primary immunodeficiency disease (PIDD) encompasses more than 340 different disorders of genetic origin characterized by an intrinsic defect in the immune system.Citation1–Citation3 Each PIDD is rare, but the global prevalence of PIDD is not negligible, varying from 4.4 to 4.98 per 100,000 inhabitants.Citation4 More than 50% of PIDDs are due to a defect in antibody production. PIDD patients exhibit an increased susceptibility to infections with longer and more frequent infectious episodes, due to a large variety of bacteria, parasites, and fungal agents, and less often viruses.Citation5 Antibody-deficiency patients mainly have infections involving the upper and lower respiratory tracts and the gastrointestinal system.Citation6 In PIDD children, B-cell defects usually manifest later than T-cell defects, because maternal immunoglobulin G (IgG) levels are still present in the neonatal circulation during the first months of life. In these patients, infections tend to be progressive and unremitting.Citation5 Repeated or chronic infection may lead to long-term organ damage.

Ig-replacement therapy (IgRT) aims to restore circulating IgG levels, thus conferring a convenient protection against infections. The mechanisms of action of IVIg are complex, involving modulation of expression and function of Fc receptors, interference with activation of complement and the cytokine network, and effects on dendritic cells, T cells, and B cells.Citation7 IgRT has been demonstrated to decrease the risk of severe infections, improve quality of life (QoL), prolong survival,Citation8–Citation11 and to be cost-effective.Citation12 With early diagnosis and adequate treatment, the long-term prognosis can be excellent.Citation13 The optimal dose for replacement therapy (RT) in PIDD is still not known;Citation14,Citation15 however, it is clear that higher IgG-trough levels decrease hospitalizations due to bacterial infectionCitation16 and can decrease the rate of other infections as well.Citation17,Citation18 Current guidelines promote the role of IgRT in the prevention of infection in PIDD patients, including pediatric patients.Citation19 Titration of dose is based on serum level, but has to be monitored by clinical response.Citation14,Citation15 The posology in children and adolescents (aged 0–18 years) is not different to that of adults, as the posology for each indication is given by body weight and adjusted to the clinical outcome of the aforementioned conditions.Citation20 Trough (predose) blood levels of IgG can be evaluated more frequently initially, and at least once a year after that, to determine if there has been a change in the pharmacokinetics and resultant blood levels of IgG in a specific individual. Ig-dose adjustments are obviously necessary during childhood related to normal growth, or during pregnancy.Citation19

Approximately half of PIDD patients are receiving IgRT,Citation4 most often as a lifelong treatment. In France in 2006, the population of patients receiving IgRT was estimated to be 1,500–1,800 patients.Citation21 Half of them might be children or young adults. With these patients, the choice of route and place for IgRT administration is of paramount importance to limit the burden of the treatment.

IgRT was first administered by intravenous Ig (IVIg), then the subcutaneous (SC) route became available. IVIg is most often delivered at hospital, whereas SCIg is used in home-based treatment. IVIg and SCIg share similar efficacy for preventing infections.Citation22–Citation26 SCIg allows more stable serum IgG levels between injections,Citation10,Citation27–Citation29 and results in normalized or high serum IgG trough concentrations.Citation21,Citation30–Citation32 Local reactions are more frequent with SCIg, whereas general systemic reactions are more often observed with IVIg.Citation33 SCIg RT is easy for children to learn and handle, often obviating the need for an infusion nurse.Citation6,Citation10,Citation31,Citation32

Health-related QoL (HRQoL) and satisfaction measurements are important issues, particularly for lifelong preventive treatment. Most studies on patients’ QoL and satisfaction with substitutive immunotherapy have mixed cohorts of children and adult patients,Citation34,Citation35 and few have reported results of specific analyses on pediatric patients.Citation30–Citation32,Citation36–Citation40 These cohorts however included a few children (aged 8–37 years), and most of them were receiving IVIg. As far as we know, we report here the most important cohort of pediatric patients followed up in real-life conditions (SCIg or IVIg, at home or at hospital) with special emphasis on HRQoL and satisfaction regarding IgRT.

Subjects and methods

The objective of the VISAGES study was to describe a cohort of PIDD children receiving IgRT in real-life conditions and over a 1-year follow-up, with special emphasis on IgRT, QoL, and satisfaction. This was a prospective study conducted in France between March 2011 and March 2014. PIDD patients aged 5–15 years receiving IgRT for at least 3 months prior to enrollment and who planned to pursue IgRT for at least 12 further months were eligible for the study. The noninterventional nature of the research protocol was confirmed by the French ethics committee (Comité de Protection des Personnes Ile de France V). The French medical research data-processing advisory committee (Comité Consultatif sur le Traitement de l’Information en Matière de Recherche dans le Domaine de la Santé) and the French information-technology and privacy commission (Commission Nationale de l’Informatique et des Libertés) approved the research protocol and related data collection. Parents or guardians of the enrolled children gave written consent after being fully informed on the aims and constraints of the study.

Patients were recruited by hospital centers that were highly experienced in the management of PIDD (16 centers). Collected data included demographic and biometric data. The type, number, and severity of infectious events within the 12 months preceding enrollment and over the follow-up period were reported. Severe infections were defined as meningitis, pneumonia, sepsis, osteitis, or visceral abscess. History of IgRT was collected. IgG serum concentration was reported when monitored. QoL was assessed by the self-administered Child Health Questionnaire – parental form (CHQ-PF50).Citation41 The CHQ-PF50 focuses on the physical and psychosocial functioning and well-being of the child and his or her family, and aggregates 15 concepts in total. Higher scores indicate a better HRQoL. The CHQ-PF50 is a widely used and valid generic questionnaire, and may be used for patients 5–15 years old without adaptation. Patients’ or parents’ satisfaction was assessed by the Life Quality Index (LQI),Citation42 a disease-specific self-questionnaire that comprises three independent factors: treatment interference (factor I), therapy-related problems (factor II), and therapy settings (factor III). The LQI consists of 15 statements, each rated on a 7-point Likert response scale. Validated French translations of the CHQ-PF50 and LQI were used. The LQI has the advantage of good responsiveness to change.Citation43 Strategies combining generic and disease-specific evaluation of QoL are encouraged.Citation43

The annual incidence rates of moderate and severe infections were estimated from Poisson regression models using the natural logarithm of the prospective follow-up duration as offset term. LQI scales and CHQ-PF50 dimensions were compared between patients receiving hospital-based IVIg and those treated with SCIg at home using a mixed model with route and place for administration as fixed factors and study center as random factor. Changes in LQI scores between patients who switched from hospital-based IVIg to home-based SCIg were analyzed by the Mann–Whitney U test. Tests were two-sided, and the statistical significance threshold was set at 0.05. To deal with the inflation of type 1 error due to multiple comparisons, P-values were adjusted by the Bonferroni method when comparing the 14 subscales of the CHQ-PF50. Statistical analysis was conducted with SAS 9.3 software (SAS Institute, Cary, NC, US).

Results

Status at enrollment

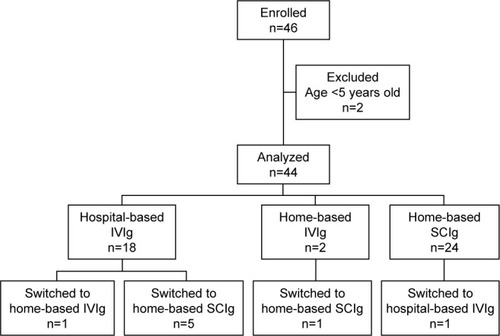

A total of 46 children entered the study. Two enrolled patients were less than 5 years old, and were promptly with-drawn from the study. Therefore, the analysis involved 44 patients meeting the eligibility criteria. They were mainly recruited in pediatric medicine departments (13 centers for 38 patients), internal medicine departments (two centers for five patients) and/or clinical immunology departments (one center for one patient); 39 of 44 had at least one follow-up visit, and 30 patients had one measure of LQI at inclusion and at least one during follow-up (). Characteristics of the 44 analyzed patients are summarized in . Patients were suffering from IgG-subclass deficiency (n=14), hypogammaglobulinemia (n=8), X-linked agammaglobulinemia (n=7), agammaglobulinemia (n=2), common variable immunodeficiency (n=2), or other miscellaneous disorders (n=11). Eleven patients (25%) had concomitant asthma. IgRT was ongoing for 5.6±4.5 years at entry in the study. Since IgRT initiation, 22 patients (50%) had switched from IVIg to SCIg, and five patients (11.4%) had switched from SCIg to IVIg. Past switches from IVIg to SCIg had been largely driven by patient request and physician willingness to preserve patient activity. Tolerability concerns had been the reason for switching from SCIg to IVIg in two of five patients.

Table 1 Population characteristics

Clinical and biological follow-up

Three patients suffered a total of five infections during the 12-month follow-up period (two SCIg and one IVIg). Three of five infectious episodes were pneumonias. One patient with humoral deficiency in a context of anhidrotic ectodermal dysplasia treated with IVIg had three severe infections. During follow-up, lowest serum IgG levels were 9.89 g/L, 10.1 g/L, and 14.9 g/L for each of these three patients. The incidence rate of severe infections was 0.15 [0.04–0.6] patient-year. In addition, 16 patients suffered a total of 54 moderate infections (21 bronchitis in six children and nine otitis in three). Among the 39 patients analyzed for follow-up, 33 (84.6%) had at least one dosage of serum IgG. Only one patient had one dosage of IgG <5 g/L during follow-up.

Ig-replacement therapy

At inclusion in the study, 18 (40.9%) patients were receiving IVIg at hospital, two (4.6%) were receiving IVIg at home, and 24 (54.6%) were treated by SCIg at home. Patients treated by IVIg were receiving 527±233 mg around once a month; patients treated by SCIg were receiving 113±43 mg 4.2±0.8 times per month. Globally, the monthly dose of IgG was 632±221 mg/kg for IVIg and 466±177 mg/kg for SCIg (P=0.02). Trough-IgG levels ranged from 3.2 to 14.9 g/L (mean 9.1±2.4 g/L). Three patients had suffered at least one severe infection within the 12 months before inclusion in the study.

Patients were followed up for 359±76 days (range 90–454 days). Five patients switched from hospital-based IVIg to home-based SCIg, one patient switched from home-based IVIg to home-based SCIg, one patient replaced home-based SCIg with hospital-based IVIg, and one patient switched from hospital-based IVIg to home-based IVIg. Therefore, six patients replaced hospital-based with home-based IgRT. In five of six patients, switches were made at the patient’s request. According to the physician, good understanding of advantages and constraints of home-based treatment by the patient was a prerequisite for switching from hospital to home. At the end of the follow-up, 13 patients were receiving hospital-based IVIg, two patients were receiving IVIg at home, and 29 patients were being treated by SCIg at home.

Satisfaction and quality of life

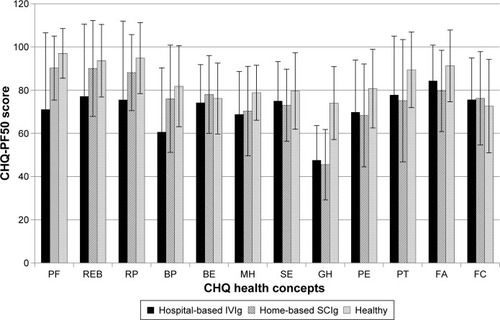

At inclusion, LQI scales, namely factors I (treatment interference), II (therapy-related problems), and III (therapy setting), were documented by 12 patients receiving hospital-based IVIg and 17 patients receiving SCIg at home. Results are provided in . Whereas no significant differences were found on factors I and II, factor III was significantly higher in patients with home-based SCIg, suggesting less disruption in daily life. Since only one patient documented with the LQI was receiving IVIg at home, there was no possible comparison with hospital-based IVIg or home-based SCIg. The CHQ-PF50 was completed by 38 patients. Some subscales of the CHQ-PF50 were altered, although the differences did not reach statistical significance, in PIDD children when compared to healthy children (): physical functioning in IVIg patients, bodily pain, general health, and parental impact – time. QoL was globally similar in patients receiving hospital-based IVIg and patients on home-based SCIg (). There was no improvement in any subscale of the CHQ-PF50 in patients who switched from IVIg to SCIg when compared to patients who pursued the same regimen (either IVIg or SCIg) (). By contrast, LQI factor III (therapy setting) significantly improved with the switch from hospital-based IVIg to home-based SCIg (P=0.04), whereas LQI factors I and II did not vary ().

Figure 2 CHQ-PF50 in PIDD children by route of infusion (n=38).

Abbreviations: CHQ-PF50, Child Health Questionnaire – parent form; PIDD, primary immunodeficiency disease; PF, physical functioning; REB, role/social – emotional/behavioral; RP, role/social – physical; BP, bodily pain (discomfort); BE, behavior; MH, mental health; SE, self-esteem; GH, general health; PE, parental impact – emotional; PT, parental impact – time; FA, family activity; FC, family cohesion; IVIg, intravenous Ig; SCIg, subcutaneous Ig; IgRT, immunoglobulin replacement therapy.

Table 2 Life Quality Index scale at inclusion

Table 3 CHQ-PF50 at inclusion (n=38)

Table 4 Evolution of CHQ-PF50 during follow-up

Table 5 Evolution of Life Quality Index scores during follow-up

Patient preference

Six of 18 patients treated at hospital expressed willingness to be treated at home instead at enrollment in the study. Five of six switched to home-based IgRT during follow-up. On the other hand, two patients treated at home preferred to be treated at hospital instead. Place of administration did not change over the follow-up. One patient expressed a preference for home-based treatment at the end of study, and the other patient had no opinion. These results suggest that physicians pay attention to their patients’ wishes.

Discussion

We report here cross-sectional and longitudinal data of 44 children 5–15 years old with PIDD who were recruited in 16 French pediatric medicine and internal medicine departments.

PIDD impacts physical dimensions of QoL and family activities

Data on QoL of PIDD children are scarce. We found few studies in PIDD children that had used the CHQ-PF50 for evaluation of QoL.Citation24,Citation39,Citation44–Citation46 In comparison with healthy children, our patients rated lower for physical functioning (IVIg patients), bodily pain, general health, and parental impact – time, although the differences did not reach significance. Similar results have been reported previously.Citation37–Citation40,Citation44 We found no difference on the behavioral subscale, as previously highlighted by Titman et al.Citation40

Gardulf et alCitation22 reported HRQoL and satisfaction in 15 Swedish children less than 14 years old switching from hospital-based IVIg to home-based SCIg. At baseline (ie, before the switch), their patients exhibited a lower level of global health and general health perception, but higher scores for physical functioning, role – physical, and bodily discomfort than patients treated with hospital-based IVIg in the VISAGES cohort. Family activities and parental emotions were more impaired and parental impact on time was greater in Gardulf et al’s patients. Zebracki et al stated that PIDD children receiving IV IgRT had a level of QoL similar to those suffering from juvenile inflammatory arthritis (JIA), but that they scored lower than the JIA group with respect to perception of general health and limitations on parental time and family activities.Citation39 Comparing the CHQ-PF50 scores of patients with JIA, we found that PIDD children had lower scores for role – social/emotional/behavioral, role – physical, mental health, general health perception, and parental impact – time, but differences did not reach significance.

Place and route of IgRT had no impact on generic QoL, but impacted patient satisfaction with IgRT

QoL was globally similar in patients receiving hospital-based IVIg and patients with home-based SCIg. There was no difference between hospital-based IVIg and home-based SCIg on LQI factor I (treatment interference) or LQI factor II (therapy-related problems), but QoL related to therapy setting was significantly higher (P=0.0003) in patients receiving home-based SCIg. SCIg has already been reported to increase patient and family satisfaction with IgRT.Citation47

Switch from hospital-based IVIg to home-based SCIg had no impact on QoL, but improved satisfaction with IgRT

No difference was found on CHQ-PF50 subscores between patients having switched from hospital-based IVIg to home-based SCIg and those who pursued the same regimen, but comparisons suffered from an evident lack of power. Similar results have recently been reported in a small study involving five patients.Citation46 Other authors have reported significant improvements in areas related to the children’s social functioning,Citation24,Citation44,Citation45 general health,Citation24,Citation36,Citation44,Citation45 parents’ life situation,Citation24,Citation36,Citation44 and family functioning.Citation36,Citation44,Citation45 Children had improved social functioning and fewer missed school days.Citation24,Citation44 It remains unclear if improvement in QoL is related to change in IgRT route or change in administration setting. SC administration is closely related to home-based treatment, while IVIg is most often administered at hospital. The review of 25 studies not specifically addressing children noted that though transition from hospital-based IVIg to home-based SCIg therapy improved HRQoL, this improvement seemed to be largely related to home therapy.Citation24 Home-based IVIg compared to hospital-based IVIg improves independence and convenience and lessens disruption of activities.

In the VISAGES study, only five patients switched from hospital-based IVIg to home-based SCIg, and lack of power could at least partially explain the absence of improvement, in contrast with other studies. However, even when crude numbers were examined, there was no evident trend toward improvements in some areas of QoL. This could also be due to higher baseline values, especially in areas related to parental impact and family activities, perhaps reflecting specificities of health systems. Differences in methods could also be plausible explanations. In Gardulf et al,Citation44 patients were eligible if they accepted to switch from hospital-based IVIg to home-based SCIg, whereas the VISAGES study was conducted in real-life conditions and patients switched mostly at their own request. Some patients had switched before inclusion in the study, and a previous switch may have optimized QoL. Finally, it has been suggested that tools measuring generic QoL may have too low a responsiveness to change.

The LQI evaluated specific QoL in PIDD patients. Whereas at inclusion, no difference was found between hospital-based IVIg and home-based SCIg on factors measuring treatment interference and therapy-related problems, factor III (therapy setting) was significantly higher in patients receiving home-based SCIg. Switch from hospital-based IVIg to home-based SCIg led to a significant improvement in LQI factor III. Significant improvements in LQI scores with switch to home-based treatment have already been reported.Citation8,Citation32,Citation35,Citation44 We found the same results in a population of adult patients,Citation48 and we concluded that satisfaction regarding IgRT cannot be confounded with QoL and that generic measures of QoL encompass different underlying concepts than the LQI.

Patient preference

Patient preference is not univocal. Not all patients prefer SC therapy when given a choice.Citation49 For children, some parents may prefer them to receive injections at hospital because of the ease of organization and the quality of care and follow-up, while others would prefer home-based treatment due to the lower impact on parents’ work and daily activities. Numerous factors may influence the patient’s preference for hospital-based or home-based treatment, including accessibility to infusion center, ability of the patients or their parents to learn the infusion technique, safety, security, and cleanliness of the home.Citation50 Ten of 18 patients who at entry were treated at hospital and all but two patients who were treated at home confirmed that the actual place of administration was their preference. In a survey conducted by an association of PIDD patients in 2006 following the availability of SCIg and the introduction of home-based treatment, the patients declared they were satisfied by the route and place of administration if they were the results of their own choices.Citation51 In other studies, families have reported they prefer the shorter, more frequent infusions at home to the more disruptive and lengthy visits to a hospital.Citation32,Citation52 Moreover, parents and children have high-lighted greater feelings of independence with home-based therapy.Citation31 Generally, after having been switched from IVIg to SCIg, children and their parents reported that they preferred home-based SCIg.Citation44,Citation24 Choosing the right patient, providing proper support, and managing expectations are crucial to ensuring that patients with PIDD achieve the maximum benefit from therapy.

Limitations

This study has some limitations. Due to its observational nature, visits were not prescheduled. Infectious events were documented retrospectively by the physician at further visits. Residual IgG levels were not monitored on a regular basis. Switches from IVIg to SCIg or from hospital-based to home-based treatment were decided in real-life conditions and were not randomized. Therefore, the group of patients whose modalities of IgRT remained unchanged cannot be considered a control group. Despite only a small series of pediatric PIDD patients receiving IgRT having been published before now and the fact that we report one of the most important cohorts, our population consisted of only 44 patients.Citation30–Citation32,Citation36–Citation40 Further studies involving a larger number of patients are warranted.

Conclusion

This study confirmed that PIDD impairs children’s QoL. Home-based SCIg compared to IVIg was associated with higher satisfaction regarding IgRT, but patient preference was not univocal. Therefore, hospital-based IgRT and home-based IgRT must be considered as options to be proposed to the patient. IgRT is a long-term therapy, and patients’ wishes may vary over time. The high level of satisfaction expressed by the patients suggests that physicians pay attention to their patients’ preferences.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank all participants who included pediatric patients in the VISAGES study: M Abdelhadi (MD), Provins, France; N Aladjidi (MD), Paris, France; A Auvrignon (MD), Paris, France; B Bienvenu (MD, PhD), Caen, France; G Couillaut (MD), Dijon, France; I Hau-Rainsart (MD), Créteil, France; E Jezioksi (MD), Montpellier, France; G Kanny (MD), Nancy, France; F Mazinfue (MD), Lille, France; J Mulliez-Petitpas (MD), Poitiers, France; M Munzer (MD), Reims, France; M Ouachée (MD), Paris, France; I Pellier-Landreau (MD), Angers, France; A Salmon (MD), Vandoeuvre-les-Nancy, France.

Disclosure

The study was sponsored by Octapharma France. The sponsor validated the study design, participated in the interpretation of data, had no role in the writing of the study report, and supported the decision to submit the manuscript for publication. BB, GJC, CH, PC, and RJ are part of the scientific committee for the VISAGES study and earned fees from Octapharma. IP, NA, AA, PC, GJC, RJ, BB, and CH were investigators for the VISAGES study. BB, PC, GJC, CH, and RJ take part in several scientific boards and also in several studies led by Octapharma. PC works as an independent statistician and earned fees from Octapharma to conduct the statistical analysis and draft the manuscript. The authors report no other conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- NotarangeloLCasanovaJLConleyMEPrimary immunodeficiency diseases: an update from the International Union of Immunological Societies Primary Immunodeficiency Diseases Classification Committee Meeting in Budapest, 2005J Allergy Clin Immunol2006117488389616680902

- Al-HerzWBousfihaACasanovaJLPrimary immunodeficiency diseases; an update on the classification from the international union of immunological societies expert committee for primary immunodeficiencyFront Immunol2014516224795713

- PicardCAl-HerzWBousfihaAPrimary immunodeficiency diseases: an update on the classification from the International Union of Immunological Societies Expert Committee for Primary Immunodeficiency 2015J Clin Immunol201535869672626482257

- GathmannBBinderNEhlSKindleGThe European Internet-based patient and research database for primary immunodeficiencies: update 2011Clin Exp Immunol20111673479491 retracted

- ChampiCPrimary immunodeficiency disorders in children: prompt diagnosis can lead to lifesaving treatmentJ Pediatr Health Care2002161162111802116

- GardulfAImmunoglobulin treatment for primary antibody deficiencies: advantages of the subcutaneous routeBioDrugs200721210511617402794

- NegiVSElluruSSibérilSIntravenous immunoglobulin: an update on the clinical use and mechanisms of actionJ Clin Immunol200727323324517351760

- NicolayUKiesslingPBergerMHealth-related quality of life and treatment satisfaction in North American patients with primary immunedeficiency [sic] diseases receiving subcutaneous IgG self-infusions at homeJ Clin Immunol2006261657216418804

- GardulfANicolayUReplacement IgG therapy and self-therapy at home improve the health-related quality of life in patients with primary antibody deficienciesCurr Opin Allergy Clin Immunol20066643444217088648

- MisbahSSturzeneggerMHBorteMSubcutaneous immunoglobulin: opportunities and outlookClin Exp Immunol2009158Suppl 1515919883424

- WoodPHuman normal immunoglobulin in the treatment of primary immunodeficiency diseasesTher Clin Risk Manag2012815716722547934

- BeautéJLevyPMilletVEconomic evaluation of immunoglobulin replacement in patients with primary antibody deficienciesClin Exp Immunol2009160224024520041884

- WoodPStanworthSBurtonJRecognition, clinical diagnosis and management of patients with primary antibody deficiencies: a systematic reviewClin Exp Immunol2007149341042317565605

- KobrynskiLSubcutaneous immunoglobulin therapy: a new option for patients with primary immunodeficiency diseasesBiologics2012627728722956859

- KerrJQuintiIEiblMIs dosing of therapeutic immunoglobulins optimal? A review of a three-decade long debate in EuropeFront Immunol2014562925566244

- QuartierPDebréMDe BlicJEarly and prolonged intravenous immunoglobulin replacement therapy in childhood agammaglobulinemia: a retrospective survey of 31 patientsJ Pediatr1999134558959610228295

- RoifmanCMSchroederHBergerMComparison of the efficacy of IGIV-C, 10% (caprylate/chromatography) and IGIV-SD, 10% as replacement therapy in primary immune deficiency: a randomized double-blind trialInt Immunopharmacol2003391325133312890430

- SriaroonPBallowMImmunoglobulin replacement therapy for primary immunodeficiencyImmunol Allergy Clin North Am201535471373026454315

- AguilarCMalphettesMDonadieuJPrevention of infections during primary immunodeficiencyClin Infect Dis201459101462147025124061

- European Medicines AgencyGuideline on core SmPC for human normal immunoglobulin for subcutaneous and intramuscular administration2015 Available from: http://www.ema.europa.eu/docs/en_GB/document_library/Scientific_guideline/2015/03/WC500184870.pdfAccessed May 1, 2017

- Association IRISEnquête sur le traitement substitutif en immunoglobulines auprès de patients atteints de deficits immunitaires primitifs2006 Available from: http://docplayer.fr/12693266-Enquete-surle-traitement-substitutif-en-immunoglobulines-aupres-de-patientsatteints-de-deficits-immunitaires-primitifs.htmlAccessed May 1, 2017

- GardulfANicolayUAsensioORapid subcutaneous IgG replacement therapy is effective and safe in children and adults with primary immunodeficiencies: a prospective, multi-national studyJ Clin Immunol200626217718516758340

- ChapelHMSpickettGPEricsonDEnglWEiblMMBjorkanderJThe comparison of the efficacy and safety of intravenous versus subcutaneous immunoglobulin replacement therapyJ Clin Immunol20002029410010821460

- FasthANyströmJSafety and efficacy of subcutaneous human immunoglobulin in children with primary immunodeficiencyActa Paediatr200796101474147817850391

- WassermanRLHizentra for the treatment of primary immunodeficiencyExpert Rev Clin Immunol201410101293130725182658

- Lingman-FrammeJFasthASubcutaneous immunoglobulin for primary and secondary immunodeficiencies: an evidence-based reviewDrugs201373121307131923861187

- GardulfAHammarströmLSmithCIHome treatment of hypogammaglobulinaemia with subcutaneous gammaglobulin by rapid infusionLancet199133887601621661712881

- WaniewskiJGardulfAHammarströmLBioavailability of γ-globulin after subcutaneous infusions in patients with common variable immunodeficiencyJ Clin Immunol199414290977515071

- BergerMSubcutaneous immunoglobulin replacement in primary immunodeficienciesClin Immunol200411211715207776

- ThomasMJBrennanVMChapelHHRapid subcutaneous immunoglobulin infusions in childrenLancet1993342888414321433

- AbrahamsenTGSandersenHBustnesAHome therapy with subcutaneous immunoglobulin infusions in children with congenital immunodeficienciesPediatrics1996986 Pt 1112711318951264

- GasparJGerritsenBJonesAImmunoglobulin replacement treatment by rapid subcutaneous infusionArch Dis Child199879148519771252

- CherinPMarieIMichalletMManagement of adverse events in the treatment of patients with immunoglobulin therapy: a review of evidenceAutoimmun Rev2016151718126384525

- OchsHDGuptaSKiesslingPNicolayUBergerMSafety and efficacy of self-administered subcutaneous immunoglobulin in patients with primary immunodeficiency diseasesJ Clin Immunol200626326527316783465

- DalyPBEvansJHKobayashiRHHome-based immunoglobulin infusion therapy: quality of life and patient health perceptionsAnn Allergy19916755045101958004

- HoffmannFGrimbacherBThielJPeterHHBelohradskyBHHome-based subcutaneous immunoglobulin G replacement therapy under real-life conditions in children and adults with antibody deficiencyEur J Med Res201015623824520696632

- KuburovicNBPasicSSusicGHealth-related quality of life, anxiety, and depressive symptoms in children with primary immuno-deficienciesPatient Prefer Adherence2014832333024669189

- SoresinaANacinovichRBombaMThe quality of life of children and adolescents with X-linked agammaglobulinemiaJ Clin Immunol200929450150719089603

- ZebrackiKPalermoTMHostofferRDuffKDrotarDHealth-related quality of life of children with primary immunodeficiency disease: a comparison studyAnn Allergy Asthma Immunol200493655756115609765

- TitmanPAllwoodZGilmourCQuality of life in children with primary antibody deficiencyJ Clin Immunol201434784485225005831

- HealthActCHQ IncChild Health Questionnaire Scoring and Interpretation Manual2008HealthActCHQ IncCambridge MA USA

- NicolayUHaagSEichmannFHergetSSpruckDGardulfAMeasuring treatment satisfaction in patients with primary immunodeficiency diseases receiving lifelong immunoglobulin replacement therapyQual Life Res20051471683169116119180

- JiangFTorgersonTRAyarsAGHealth-related quality of life in patients with primary immunodeficiency diseaseAllergy Asthma Clin Immunol2015112726421019

- GardulfANicolayUMathDChildren and adults with primary antibody deficiencies gain quality of life by subcutaneous IgG self-infusions at homeJ Allergy Clin Immunol2004114493694215480339

- BergerMMurphyERileyPBergmanGEImproved quality of life, immunoglobulin G levels, and infection rates in patients with primary immunodeficiency diseases during self-treatment with subcutaneous immunoglobulin GSouth Med J2010103985686320689467

- VultaggioAAzzariCMilitoCSubcutaneous immunoglobulin replacement therapy in patients with primary immunodeficiency in routine clinical practice: the VISPO prospective multicenter studyClin Drug Investig2015353179185

- AbolhassaniHSadaghianiMSAghamohammadiAOchsHDRezaeiNHome-based subcutaneous immunoglobulin versus hospital-based intravenous immunoglobulin in treatment of primary antibody deficiencies: systematic review and meta analysisJ Clin Immunol20123261180119222730009

- BienvenuBCozonGHoarauCDoes the route of immunoglobin replacement therapy impact quality of life and satisfaction in patients with primary immunodeficiency? Insights from the French cohort “Visages”Orphanet Journal of Rare Diseases20161118327334100

- Skoda-SmithSTorgersonTROchsHDSubcutaneous immunoglobulin replacement therapy in the treatment of patients with primary immunodeficiency diseaseTher Clin Risk Manag2010611020169031

- BergerMPrinciples of and advances in immunoglobulin replacement therapy for primary immunodeficiencyImmunol Allergy Clin North Am2008282413437x18424340

- KittnerJMGrimbacherBWulffWJägerBSchmidtREPatients’ attitude to subcutaneous immunoglobulin substitution as home therapyJ Clin Immunol200626440040516783533

- DamsETvan der MeerJWSubcutaneous immunoglobulin replacement in patients with primary antibody deficienciesLancet19953458953864