Abstract

Objective

Among adults with diabetes, depression is associated with poorer adherence to cardiometabolic medications in ongoing users; however, it is unknown whether this extends to early adherence among patients newly prescribed these medications. This study examined whether depressive symptoms among adults with diabetes newly prescribed cardiometabolic medications are associated with early and long-term nonadherence.

Patients and methods

An observational follow-up of 4,018 adults with type 2 diabetes who completed a survey in 2006 and were newly prescribed oral antihyperglycemic, antihypertensive, or lipid-lowering agents within the following year at Kaiser Permanente Northern California was conducted. Depressive symptoms were examined based on Patient Health Questionnaire-8 scores. Pharmacy utilization data were used to identify nonadherence by using validated methods: early nonadherence (medication never dispensed or dispensed once and never refilled) and long-term nonadherence (new prescription medication gap [NPMG]: percentage of time without medication supply). These analyses were conducted in 2016.

Results

Patients with moderate-to-severe depressive symptoms had poorer adherence than nondepressed patients (8.3% more patients with early nonadherence, P=0.01; 4.9% patients with longer NPMG, P=0.002; 7.8% more patients with overall nonadherence [medication gap >20%], P=0.03). After adjustment for confounders, the models remained statistically significant for new NPMG (3.7% difference, P=0.02). There was a graded association between greater depression severity and nonadherence for all the models (test of trend, P<0.05).

Conclusion

Depressive symptoms were associated with modest differences in early and long-term adherence to newly prescribed cardiometabolic medications in diabetes patients. Interventions targeting adherence among adults with diabetes and depression need to address both initiation and maintenance of medication use.

Introduction

Medication nonadherence is a modifiable contributor to morbidity and mortality associated with chronic conditions, such as diabetes and cardiovascular disease, and thus serves as a potential target for tertiary preventive interventions.Citation1 The societal burden of medication nonadherence is substantial; in the USA, nonadherence has been estimated to account for 125,000 annual deaths, a major proportion of preventable hospitalizations, and to carry economic costs between $100 and $300 billion each year.Citation2 Past research to identify risk factors for medication nonadherence has focused on nonadherence among ongoing (prevalent) medication users,Citation3,Citation4 termed secondary nonadherence. However, studies on secondary nonadherence underestimate overall medication nonadherence because they systematically exclude people who are nonadherent in the earliest phases of treatment, that is, those who never fill a medication prescription or those who fill an initial prescription but never refill it.Citation5–Citation7 Nonadherence at this early phase is important because such individuals do not go on to become ongoing users of the medication and therefore do not receive the potential benefits of treatment as a prevention of premature morbidity and mortality. Recent methodological innovations allow the characterization of adherence in new prescription cohorts (patient cohorts in which baseline is the date of first medication prescribed), thus enabling researchers to more comprehensively evaluate the public health burden and correlates of nonadherence over the entire course of treatment.Citation6

Depression, which is common among people with chronic diseases including diabetes,Citation8–Citation13 has been identified as a risk factor for secondary medication nonadherence among adults with diabetes.Citation14–Citation16 In a recent systematic review, depression and out-of-pocket costs were among the few patient-, treatment-, and system-level factors that demonstrated consistent, significant associations with adherence to diabetes medications across multiple studies employing differing methods.Citation4 Although reasons for the association between depression and secondary adherence are not fully established, related research has found that, among people with diabetes, those with comorbid depression have poorer self-care in multiple domains than nondepressed counterparts.Citation14 Depression has negative effects on cognitive and affective functioning that may serve as barriers to participation in self-care broadly and medication adherence specifically. For example, depression negatively affects motivation and executive functioning and includes psychological effects such as hopelessness, helplessness, poor self-efficacy, and feelings of low self-worth, all of which may interfere with activities needed for effective self-care.

It is not known whether the well-established association between depression and secondary medication adherence extends to early nonadherence. This knowledge is important for understanding the overall public health impact of depression, which may be underestimated in the literature on secondary adherence. The present study examined whether depressive symptoms among adults with type 2 diabetes were associated with initiation and maintenance of newly prescribed cardiometabolic therapies. It is hypothesized that patients with greater depressive symptom severity would have poorer early and long-term adherence than those without depressive symptoms.

Patients and methods

Setting and study population

Kaiser Permanente Northern California (KPNC) is a large integrated health care delivery system serving ~30% of the catchment population of Northern California. The KPNC membership is ethnically diverse and sociodemographically similar to the population of the region, except for the extreme tails of the income distribution.Citation17 The Diabetes Study of Northern California (DISTANCE) surveyed an ethnically stratified, random sample of adult (aged 30–75 years) health plan members from the KPNC Diabetes Registry in 2005–2006. The methods employed to construct the KPNC Diabetes Registry and the DISTANCE sample have been previously described in detail.Citation18 There were no additional exclusion criteria for the survey. The overall eligibility-adjusted response rate was 62%, yielding a final sample of 20,188 participants.Citation18 Participants completed a written survey (33.1%), a web-based survey (15.2%) in English, or a computer-assisted telephone interview (51.7%) in English, Spanish, Cantonese, Mandarin, or Tagalog. The KPNC Institutional Review Board (IRB) approved this study. The requirement that informed consent be obtained from study participants was waived by the IRB; answering any survey questions constituted consent.

The present study examined medication nonadherence in patients with type 2 diabetes during a period of 24 months following a new prescription order for any of three types of common cardiometabolic medications: oral antihyperglycemic agents, antihypertensive agents, and lipid-lowering agents. This study identified the 4,018 DISTANCE survey respondents who: 1) had a new prescription (index prescription) for an oral antihyperglycemic agent (n=1,481), an antihypertensive agent (n=1,620), or a lipid-lowering agent (n=917; refer for complete medication list) within 1 year following survey completion, 2) were not previously dispensed the same medication in the 2 years preceding the index prescription date, 3) had continuous pharmacy benefits for at least 2 years before and after the index prescription date, and 4) completed the survey items assessing depressive symptoms (refer for details of cohort creation).

Exposure

Depressive symptoms were assessed by using the Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ) that asks about the presence of depressive symptoms over the past 2 weeks.Citation19,Citation20 The PHQ has been widely validated as a measure for detecting the presence of clinically significant depressive disorders and is brief, easy to administer, and available in numerous languages.Citation20–Citation24 A diagnostic meta-analysis found a sensitivity of 0.80 and specificity of 0.92 for the detection of major depressive disorder.Citation25 The present study used the PHQ-8 that is most commonly used for survey research given the inability to respond appropriately and in a timely fashion to positive suicidal ideation when administered via a written survey. (The PHQ-9 includes an additional item assessing thoughts of death or self-harm and is therefore more frequently employed in the clinical setting).Citation19,Citation20 Past research has demonstrated that scores of the PHQ-8 and PHQ-9 are highly correlated (rs≥0.997), both measures have similar operating characteristics, and identical scoring cut-points can be used.Citation19,Citation20 The PHQ-8 is scored from 0 to 24 and based on established cut-points; depressive symptom severity was coded as “none” (score 0–4), “mild” (score 5–9), or “moderate/severe” (score ≧10).Citation20,Citation23

Outcomes

Pharmacy prescribing and dispensing data for the index prescriptions were used to calculate several indicators of nonadherence. Although pharmacy utilization is a distinct behavior from medication-taking, prior research has established the validity of this method.Citation6,Citation26 Early nonadherence was defined as either no dispensing of the index prescription within 60 days of the date it was ordered or the dispensing of the index prescription once but no additional dispensing of that medication (ie, no refill) within the period defined by the number of days’ supply of medication dispensed plus a 90-day grace period. A continuous and comprehensive measure of nonadherence, new prescription medication gap (NPMG), was also calculated. This measure provides an estimate of the percentage of time without a supply (ie, gaps) of the index prescription during the 24 months after the initial order.Citation6 NPMG is calculated by using the daily dosage of medication prescribed, the number of pills dispensed, and dispensing dates over 24 months to estimate gaps in medication supply. By using NPMG, the patients were categorized as “nonadherent” overall if they lacked medication supply for at least 20% of the time (ie, NPMG >20%). For patients who had more than one new prescription, only adherence to the first medication prescribed for any of the three indications was assessed. For patients whose dispensing data indicated a switch from the index prescription to an alternate medication within the same drug class between 3 months prior and 1 month after the discontinuation date, the discontinuation of the index prescription was considered to be clinically recognized rather than an indicator of nonadherence. In such instances, follow-up as of the date of switch to the alternate medication was censored.

Covariates

Participants self-reported sociodemographic information (ie, age; gender; race/ethnicity: white, African–American, Latino, Asian–American, Filipino, or other/unknown/multiracial; marital status: married/partnered, single/separated/divorced/widowed) and a history of any of the following: myocardial infarction, cerebrovascular accident, coronary artery disease (as indicated by coronary artery bypass surgery or angioplasty), lower extremity amputation, or renal failure requiring dialysis or transplantation. Missing survey data on diabetes complications were imputed using data on complications obtained from the electronic medical record.

Data analysis

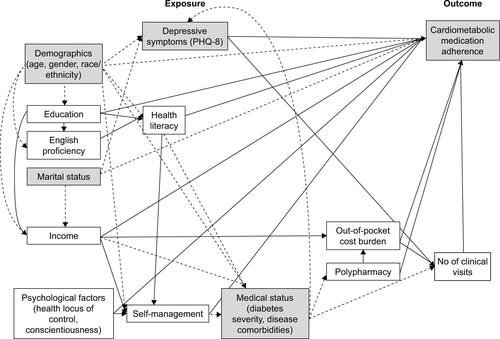

Modified Poisson regression models were specified to estimate the relative risk (RR) of nonadherence for those with mild or moderate/severe depressive symptoms compared with those with none,Citation27 and modified least squares regressionCitation28 was employed to generate the predicted probability for each measure of nonadherence for each depressive symptom category. To assess whether nonadherence was greater among those with higher depression symptom severity, a Cochran–Armitage test for trend was applied to the predicted probabilities from the unadjusted and adjusted models for dichotomous outcomes (ie, adherent vs nonadherent). A generalized linear regression model was specified to evaluate the relationship between depressive symptom category and the percentage of time without pill supply (continuous NPMG). A directed acyclic graph (DAG) depicting hypothesized causal relationships and temporal ordering between the exposure (depressive symptom category) and outcomes of interest (measures of adherence) was constructed (refer , for the graph and its interpretation).Citation29,Citation30 Then, established DAG rules were used to determine the subset of covariates (potentially confounding variables) required in adjusted models to estimate the unbiased direct effect of depressive symptoms on medication adherence. In accordance with the findings from the present DAG analysis, each model was adjusted by including age, gender, race/ethnicity, marital status, and diabetes complications as covariates (described in Covariates section). All the models were expansion-weighted to accommodate the race/ethnicity-stratified sampling design (nonproportional sampling fractions) of the original DISTANCE survey and further weighted for survey nonresponse by using the Horvitz–Thompson method.Citation31 Analyses were completed in 2016.

Results

Among 4,018 patients who were prescribed a new cardio-metabolic medication, 2,573 (64.0%) patients were categorized as having no depressive symptoms, and the remaining 1,445 (36.0%) were categorized as having mild (935, 23.3%) or moderate/severe (510, 12.7%) depressive symptoms. Depressive symptoms were significantly associated with younger age, female gender, low educational attainment, race/ethnicity (particularly Latinos), unmarried status, the history of diabetes complications, and number of medications ().

Table 1 Demographic and clinical characteristics by depressive symptom category (n=4,018)

Overall, early nonadherence was common, with 27.9% of patients either never filling or never refilling their newly prescribed cardiometabolic medication. Over the course of 2 years following a new prescription, on average, patients were lacking medications for 194 days (ie, NPMG =27%), and 39.3% of patients were categorized overall as nonadherent (ie, NPMG >20%).

Associations between depressive symptoms and nonadherence

Nonadherence to cardiometabolic medications was greater among patients with moderate/severe depressive symptoms than patients with no depressive symptoms. This pattern held for all indicators of nonadherence (). There was an 8.3% increase in early nonadherence (RR =1.33, P=0.006), a 7.8% increase in overall nonadherence (NPMG >20%; RR =1.22, P=0.02), and 4.9% greater days without pill supply (NPMG; P=0.002). The point estimates changed only minimally after adjustment for age, gender, race/ethnicity, marital status, and diabetes complications. Only the model for NPMG specified as a continuous variable remained statistically significant after adjustment (3.7% greater days without supply among patients with moderate/severe depressive symptoms than patients with no depressive symptoms; P=0.02). However, the Cochran–Armitage test for trend consistently demonstrated that nonadherence increased significantly as depressive symptoms increased with and without adjustment (early nonadherence: P<0.0001 [unadjusted] and P=0.0028 [adjusted]; and overall nonadherence [NPMG >20%]: P=0.0002 [unadjusted] and P=0.0118 [adjusted]). Similarly, the linear regression model also demonstrated a significant linear trend between depression and nonadherence (NPMG: P=0.0007 [unadjusted] and P=0.019 [adjusted]).

Table 2 Association between depressive symptom severity and cardiometabolic medication adherence for 4,018 adults with type 2 diabetes

Discussion

Among adults with diabetes, associations between depressive symptom severity and adherence to cardiometabolic medications were modest for indicators of both early and long-term adherence over 24 months, which extends prior research focused on secondary adherence.Citation14,Citation15 These findings are relevant because initiating and maintaining long-term adherence are important for optimal control of cardiometabolic risk factors and for prevention of associated diabetes complications and mortality.

The 5% greater rate of early nonadherence among patients with depressive symptoms is clinically significant, given these patients never become ongoing medication users. A graded pattern was observed between greater depressive symptom severity and poorer adherence. The finding from the present study differs from prior research in hypertensive patients from the same source population (KPNC) which did not detect an association between depression and early nonpersistence to antihypertensive medications.Citation32 Unlike the prior study that classified depression based on electronic medical records (ie, clinically recognized depression), the present study classified depression based on direct assessment of patient-reported symptoms using the PHQ-8. Thus, the present sample was not limited to people whose depression was clinically recognized.Citation9,Citation33 This expanded exposure definition may explain the difference in findings and supports the value of patient-reported outcome measures and the use of dimensional measures for studies of mental disorders such as depression. The findings are consistent with prior research reporting that the association between depression and nonadherence is not limited to those with probable major depression.Citation34 Diabetes distress has also been associated with nonadherence; however, it is believed diabetes distress is unlikely to explain the association between depression and nonadherence. Prior research has found that the association between diabetes distress and adherence does not persist after depressive symptoms are accounted for, whereas in that study depression was independently associated with adherence after diabetes distress was taken into account.Citation35

Whereas early nonadherence reflects discrete behaviors at two specific points in time, NPMG is an aggregate indicator that reflects the cumulative effect of repeated utilization (or lack thereof) over a period of 24 months. This difference may be informative for tertiary prevention efforts, namely, the development of interventions to address suboptimal medication adherence among adults with depressive symptoms. The present findings suggest that medication adherence interventions for people with comorbid depression may need to be applied both at the initiation of treatment and on an ongoing basis to sustain adherence over time.

Limitations

Some study limitations should be considered. Patterns of adherence were examined for a limited set of cardiometabolic medication classes and indications, and only the first new prescription was included within a medication class. Thus, the study findings may not generalize to other patient populations, multiple prescriptions within therapeutic classes, ongoing use of medications, or other types of medications. The estimates of nonadherence based on pharmacy utilization data are conservative, given that it is unknown whether any medications dispensed were actually consumed because medication-taking and prescription filling are distinct behaviors. Research indicates that the use of pharmacy utilization measures of adherence results in lesser effects for depression than when self-report adherence measures are used;Citation16 therefore, the results from the present study represent conservative estimates of the true effects of depression. Nevertheless, these findings are based on objective measures of utilization according to the methods that have been previously validated,Citation6 thus avoiding concerns of recall bias or social desirability associated with retrospective, self-reported medication adherence.

In this study, depressive symptoms were assessed at a single point in time that preceded a new prescription by no more than 1 year and based on self-report (using the PHQ-8). Although depressive symptoms fluctuate over time, evidence suggests that depression is often recurrent and chronic among adults with diabetesCitation36 and often not clinically recognized.Citation9,Citation33 The presence of consistent associations between depressive symptoms and adherence over the long term supports the enduring nature of the risk for nonadherence associated with depressive symptoms and suggests that these findings may be conservative because the observed associations may have been attenuated by the small delay between the measurement of depressive symptoms and adherence in some participants. A minority of individuals who scored in the moderate/severe range on the PHQ-8 likely would not have met criteria for major depression or another clinically significant depressive disorder and may instead have a related condition such as an anxiety disorder or diabetes distress that presents with substantial comorbid depressive symptomatology. This is not viewed as a limitation because the present findings generalize to a broader group of people, those with at least one PHQ-8 score of 10 or greater, who can be identified easily in routine practice settings. Moreover, using PHQ scores to identify patients at an increased risk for nonadherence is consistent with recommendations from a recent issue brief from the Office of the National Coordinator for Health Information Technology to develop predictive analytics based on electronic medical record data to enable targeted interventions.Citation37 The present study found a significant, graded relationship between depressive symptom severity and nonadherence for all measures, which affirms the utility of depressive symptoms as a dimensional construct in understanding its association with adherence, regardless of the extent that symptoms overlap with related constructs such as diabetes distress. Because all participants in this study were insured and received services via KPNC, which includes integrated pharmacy services, results may not generalize to disadvantaged patient populations or safety net health care settings. Although the large sample was ethnically and socioeconomically diverse, the findings may not reflect patterns in settings where access to care differs across social groups. Although initial data collection occurred in 2005–2006, depression identification, care, and adherence remain persistent clinical challenges.Citation2,Citation38 However, it is not believed that the overall relationship between depression and adherence would change substantively over time.

Conclusion

Clinicians treating patients with type 2 diabetes who prescribe new cardiometabolic therapies should be aware that those with depression are more likely to have elevated rates of nonadherence both initially and over the long term. However, it is likewise important to note that the differences attributable to depression were modest compared to the baseline high rate of nonadherence in the overall sample. Patients with type 2 diabetes and depression experience a disproportionately high burden of premature morbidity and mortality.Citation39–Citation42 The small increased probability of nonadherence among patients with type 2 diabetes and comorbid depression should not deter clinicians from initiating cardiometabolic therapies. Rather, such treatments should be offered alongside care for depression, and interventions to address adherence should be delivered longitudinally to target the barriers that depressed patients face to maintaining adherence. Promising interventions, such as the routine assessment of medication adherence, exploration of barriers and problem-solving, and use of motivational interviewing to facilitate behavior change,Citation43–Citation45 may need to be offered when medications are initiated and implemented repeatedly in a routine clinical practice. Although recognition of depression and appropriate treatment are necessary for improving depression outcomes, these alone may be insufficient to improve self-care and outcomes for people with type 2 diabetes.Citation46 To optimally treat patients with comorbid type 2 diabetes and depression and prevent diabetes complications, clinicians should pair interventions that address depressive symptoms with interventions that directly target diabetes self-care, including sustained medication adherence.Citation44,Citation47 Future research should examine the effectiveness of such paired interventions for people with comorbid diabetes and depression on adherence and clinical outcomes and evaluate interventions both at the time of initial medication prescription and over the long term.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to acknowledge the untimely loss of coauthor and mentor Wayne J Katon. Dr Katon was instrumental in building the collaborations that led to this research. He has inspired researchers for decades to improve understanding of the bidirectional relationships between depression and chronic diseases, particularly diabetes, and to endeavor to improve physical and mental health for those affected. Dr Katon’s contributions have touched the lives of countless patients, colleagues, and friends and the authors are deeply grateful. This research was supported by funding from the National Institutes of Health (R01-DK065664, R01-DK080726, R01-DK081796, P30-DK092924, NLM012355-01A1, and National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences Grant KL2 TR000421) and the Kaiser Permanente Northern California Community Benefit Program.

Supplementary materials

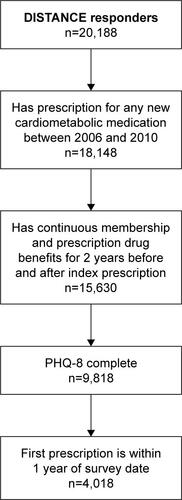

Figure S1 Flowchart of new cardiometabolic medication user cohort.

Abbreviations: DISTANCE, the Diabetes Study of Northern California; PHQ, Patient Health Questionnaire.

Figure S2 DAG demonstrating covariate selection.

Notes: Shaded box: variable included in multivariate analyses; white box: variable excluded as potential confounder and therefore not included in multivariate analyses; solid arrow: causal pathways that do not confound the association between depressive symptoms and cardiometabolic medication adherence; dotted arrow: causal pathways that potentially confound the association between depressive symptoms and cardiometabolic medication adherence in unadjusted analyses but are no longer confounders in multivariate models that include the variables identified in the shaded boxes. The DAG was constructed to illustrate the hypothesized causal relationships and time ordering between variables associated with depressive symptoms and cardiometabolic medication adherence. All of the variables represented were available in the DISTANCE data set. Analysis of the DAG followed an established process to identify which of these variables were potential confounders of the association between depressive symptoms and adherence.Citation1 This analysis revealed that adjustments for the variables in the shaded boxes (age, gender, race/ethnicity, marital status, and diabetes complications) were necessary and sufficient to address potential confounding variables, whereas variables in the white boxes were excluded as covariates because they did not function as potential confounders. Causal pathways illustrated by the gray dotted arrows are accounted for by adjustment of the identified covariates, and therefore, these relationships do not confound the association between depressive symptoms and adherence. This includes all variables with casual links to the independent variable, depressive symptoms. The remaining causal relationships (solid arrows) do not function as confounders and therefore do not require adjustment. This is visualized in the graph because variables that are causally associated with the dependent variable (variables in white boxes that have solid arrows to adherence) are not causally associated with the independent variable (these variables do not have solid arrows terminating at depressive symptoms).

Abbreviations: DAG, directed acyclic graph; DISTANCE, the Diabetes Study of Northern California; PHQ, Patient Health Questionnaire.

Table S1 Classification of cardiometabolic medications

Reference

- GreenlandSPearlJRobinsJMCausal diagrams for epidemiologic researchEpidemiology199910137489888278

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- SimpsonSHEurichDTMajumdarSRA meta-analysis of the association between adherence to drug therapy and mortalityBMJ200633375571516790458

- BenjaminRMMedication adherence: helping patients take their medicines as directedPublic Health Rep201212712322298918

- ChristensenAJHowrenMBHillisSLPatient and physician beliefs about control over health: association of symmetrical beliefs with medication regimen adherenceJ Gen Intern Med201025539740220174972

- KrassISchiebackPDhippayomTAdherence to diabetes medication: a systematic reviewDiabet Med201532672573725440507

- RaebelMASchmittdielJKarterAJKoniecznyJLSteinerJFStandardizing terminology and definitions of medication adherence and persistence in research employing electronic databasesMed Care2013518 Suppl 3S11S2123774515

- KarterAJParkerMMMoffetHHAhmedATSchmittdielJASelbyJVNew prescription medication gaps: a comprehensive measure of adherence to new prescriptionsHealth Serv Res2009445 Pt 11640166119500161

- RaebelMAEllisJLCarrollNMCharacteristics of patients with primary non-adherence to medications for hypertension, diabetes, and lipid disordersJ Gen Intern Med2012271576421879374

- AndersonRJFreedlandKEClouseRELustmanPJThe prevalence of comorbid depression in adults with diabetes: a meta-analysisDiabetes Care20012461069107811375373

- KatonWJSimonGRussoJQuality of depression care in a population-based sample of patients with diabetes and major depressionMed Care200442121222122915550802

- LiCFordESStrineTWMokdadAHPrevalence of depression among U.S. adults with diabetes: findings from the 2006 behavioral risk factor surveillance systemDiabetes Care200831110510717934145

- BouwmanVAdriaanseMCvan’t RietESnoekFJDekkerJMNijpelsGDepression, anxiety and glucose metabolism in the general Dutch population: the new Hoorn studyPLoS One201054e997120376307

- NouwenANefsGCaramlauIPrevalence of depression in individuals with impaired glucose metabolism or undiagnosed diabetes: a systematic review and meta-analysis of the European Depression in Diabetes (EDID) Research ConsortiumDiabetes Care201134375276221357362

- RoyTLloydCEEpidemiology of depression and diabetes: a systematic reviewJ Affect Disord2012142SupplS8S2123062861

- LinEHKatonWVon KorffMRelationship of depression and diabetes self-care, medication adherence, and preventive careDiabetes Care20042792154216015333477

- KatonWRussoJLinEHDiabetes and poor disease control: is comorbid depression associated with poor medication adherence or lack of treatment intensification?Psychosom Med200971996597219834047

- GrenardJLMunjasBAAdamsJLDepression and medication adherence in the treatment of chronic diseases in the United States: a meta-analysisJ Gen Intern Med201126101175118221533823

- KarterAJFerraraALiuJYMoffetHHAckersonLMSelbyJVEthnic disparities in diabetic complications in an insured populationJAMA2002287192519252712020332

- MoffetHHAdlerNSchillingerDCohort profile: The Diabetes Study of Northern California (DISTANCE) – objectives and design of a survey follow-up study of social health disparities in a managed care populationInt J Epidemiol2009381384718326513

- KroenkeKStrineTWSpitzerRLWilliamsJBBerryJTMokdadAHThe PHQ-8 as a measure of current depression in the general populationJ Affect Disord20091141–316317318752852

- KroenkeKSpitzerRLWilliamsJBLoweBThe Patient Health Questionnaire Somatic, Anxiety, and Depressive Symptom Scales: a systematic reviewGen Hosp Psychiatry201032434535920633738

- SpitzerRLKroenkeKWilliamsJBValidation and utility of a self-report version of PRIME-MD: the PHQ primary care study. Primary Care Evaluation of Mental Disorders. Patient Health QuestionnaireJAMA1999282181737174410568646

- SpitzerRLWilliamsJBKroenkeKHornyakRMcMurrayJValidity and utility of the PRIME-MD patient health questionnaire in assessment of 3000 obstetric-gynecologic patients: the PRIME-MD Patient Health Questionnaire Obstetrics-Gynecology StudyAm J Obstet Gynecol2000183375976910992206

- KroenkeKSpitzerRLWilliamsJBThe PHQ-9: validity of a brief depression severity measureJ Gen Intern Med200116960661311556941

- HuangFYChungHKroenkeKDelucchiKLSpitzerRLUsing the patient health questionnaire-9 to measure depression among racially and ethnically diverse primary care patientsJ Gen Intern Med200621654755216808734

- GilbodySRichardsDBrealeySHewittCScreening for depression in medical settings with the Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ): a diagnostic meta-analysisJ Gen Intern Med200722111596160217874169

- ParkerMMMoffetHHAdamsAKarterAJAn algorithm to identify medication nonpersistence using electronic pharmacy databasesJ Am Med Inform Assoc201522595796126078413

- ZouGA modified Poisson regression approach to prospective studies with binary dataAm J Epidemiol2004159770270615033648

- CheungYBA modified least-squares regression approach to the estimation of risk differenceAm J Epidemiol2007166111337134418000021

- GreenlandSPearlJRobinsJMCausal diagrams for epidemiologic researchEpidemiology199910137489888278

- HernanMAHernandez-DiazSWerlerMMMitchellAACausal knowledge as a prerequisite for confounding evaluation: an application to birth defects epidemiologyAm J Epidemiol2002155217618411790682

- HorvitzDGThompsonDJA generalization of sampling without replacement from a finite universeJ Am Stat Assoc195247260663685

- SchmittdielJADyerWUratsuCInitial persistence with antihypertensive therapies is associated with depression treatment persistence, but not depressionJ Clin Hypertens (Greenwich)201416641241724716533

- HudsonDLKarterAJFernandezADifferences in the clinical recognition of depression in diabetes patients: the Diabetes Study of Northern California (DISTANCE)Am J Manag Care201319534435223781889

- GonzalezJSSafrenSACaglieroEDepression, self-care, and medication adherence in type 2 diabetes: relationships across the full range of symptom severityDiabetes Care20073092222222717536067

- GonzalezJSDelahantyLMSafrenSAMeigsJBGrantRWDifferentiating symptoms of depression from diabetes-specific distress: relationships with self-care in type 2 diabetesDiabetologia200851101822182518690422

- KatonWJVon KorffMLinEHThe Pathways Study: a randomized trial of collaborative care in patients with diabetes and depressionArch Gen Psychiatry200461101042104915466678

- WilliamsAIssue Brief: Medication Adherence and Health ITOffice of the National Coordinator for Health Information Technology2014 Available from: https://www.healthit.gov/sites/default/files/medicationadherence_and_hit_issue_brief.pdfAccessed February 28, 2017

- OlfsonMBlancoCMarcusSCTreatment of adult depression in the United StatesJAMA Intern Med2016176101482149127571438

- de GrootMAndersonRFreedlandKEClouseRELustmanPJAssociation of depression and diabetes complications: a meta-analysisPsychosom Med200163461963011485116

- KatonWJRutterCSimonGThe association of comorbid depression with mortality in patients with type 2 diabetesDiabetes Care200528112668267216249537

- KatonWLylesCRParkerMMKarterAJHuangESWhitmerRAAssociation of depression with increased risk of dementia in patients with type 2 diabetes: the Diabetes and Aging StudyArch Gen Psychiatry201269441041722147809

- SullivanMDO’ConnorPFeeneyPDepression predicts all-cause mortality: epidemiological evaluation from the ACCORD HRQL substudyDiabetes Care20123581708171522619083

- MurawskiMEMilsomVARossKMProblem solving, treatment adherence, and weight-loss outcome among women participating in lifestyle treatment for obesityEat Behav200910314615119665096

- KatonWJLinEHVon KorffMCollaborative care for patients with depression and chronic illnessesN Engl J Med2010363272611262021190455

- WhiteRDPatient empowerment and optimal glycemic controlCurr Med Res Opin201228697998922429065

- LinEHKatonWRutterCEffects of enhanced depression treatment on diabetes self-careAnn Fam Med200641465316449396

- MarkowitzSMGonzalezJSWilkinsonJLSafrenSAA review of treating depression in diabetes: emerging findingsPsychosomatics201152111821300190