Abstract

Objectives

The aims of this study were to describe changes in day- and nighttime symptoms and the adherence to nasal continuous positive airway pressure (nCPAP) during the first 3-month nCPAP therapy among newly diagnosed patients with obstructive sleep apnea/hypopnea syndrome (OSAS) and to identify the effect of adherence on the changes in day- and nighttime symptoms during the first 3 months.

Methods

Newly diagnosed OSAS patients were consecutively recruited from March to August 2013. Baseline clinical information and measures of the Epworth Sleepiness Scale (ESS), Fatigue Severity Scale (FSS), Zung’s Self-Rating Depression Scale (SDS) and the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI) at baseline and the end of 3rd, 6th, 9th and 12th week of therapy were collected. Twelve weeks’ adherence was calculated as the average of each 3-week period. Mixed model was used to explore the effect of adherence to nCPAP therapy on ESS, FSS, SDS and PSQI in each 3-week phase.

Results

Seventy-six patients completed the 12-week follow-up. The mixed-effects models showed that under the control of therapy phase adherence in the range of <4 hours per night, using nCPAP could independently improve daytime sleepiness, in terms of ESS (coefficient, [95% confidence interval] unit; −4.49 [−5.62, −3.36]). Adherence at 4–6 hours per night could independently improve all variables of day- and nighttime symptoms included in this study, namely ESS −6.69 (−7.40, −5.99), FSS −6.02 (−7.14, −4.91), SDS −2.40 (−2.95, −1.85) and PSQI −0.20 (−0.52, −0.12). Further improvement in symptoms could be achieved at ≥6 hours per night using nCPAP, which was ESS −8.35 (−9.26, −7.44), FSS −10.30 (−11.78, −8.83), SDS −4.42 (−5.15, −3.68) and PSQI −0.40 (−0.82, −0.02). The interaction between adherence level and therapy phase was not significant in day- and nighttime symptoms.

Conclusion

The effect of adherence on the above-mentioned symptoms is stable through the first 3 months. Under the control of therapy phase, the nCPAP therapy effectively improves day- and nighttime symptoms with ≥4 hours adherence, and the patients can achieve a further improvement with ≥6 hours adherence.

Background

Obstructive sleep apnea/hypopnea syndrome (OSAS) is characterized by repetitive obstruction of the upper airway during sleep, causing obstructive apneas leading to oxygen desaturations and fragmentation of nocturnal sleep.Citation1,Citation2 Snoring, excessive daytime sleepiness (EDS), fatigue and depression are frequently associated. The more serious consequences of OSAS are higher risk of cardiovascular, pulmonary, vascular and cerebral diseases in patients with OSAS.

Continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) therapy has been proven to significantly reduce the risk of cardiovascular disease as well as improve daytime symptoms. Effective CPAP management reduces nighttime breathing disturbances and improves oxygenation, sleep architecture, daytime sleepiness, daytime performance and depression.Citation3–Citation8 To achieve the effectiveness of CPAP therapy, OSAS patients are suggested to use CPAP during whole nights.

However, many patients could not follow this suggestion. Several previous studies have focused on the adherence to CPAP among OSAS patients.Citation9–Citation15 Some of the studies aimed to reveal the relationship between CPAP using hours and its effects on associated symptoms.Citation10,Citation11,Citation16 Weaver et alCitation11 reported that after a 3-month therapy, a linear dose–response trend is observed between the increase in CPAP using hours and the cumulative proportion of participants obtaining normal values of Epworth Sleepiness Scale (ESS ≤10 is considered normal value), and they also found that 4 hours duration of using CPAP during the night was a cutoff point for normalized ESS score. A similar result was also reported by Antic et al.Citation10 They found that of the OSAS patients using CPAP for >7 hours, 80.6% had a normal ESS score, and of those using CPAP between 2 and 4 hours, there were 52.4% of them with normalized ESS score after 3-month therapy. Compared with the major daytime symptom, sleepiness, the relationship between adherence and normalization of fatigue and depression was rarely reported. Wang et alCitation9 reported that fatigue, depression and sleep quality were independent influencing factors of adherence. Conversely, the effect of adherence on fatigue and depression might impact the changes in symptoms as well as the subsequent adherence. Therefore, it is necessary to conduct a study to identify the effect of adherence not only on daytime sleepiness but also on fatigue, depression and sleep quality.

Furthermore, previous studies reported the effect of adherence to CPAP therapy on related clinical variables; these studies were of a before–after design and could not reveal the independent effect of adherence under the control of therapy phase on the changes in the variables over time or the interaction between adherence and therapy phase. Knowledge of the time frame for these clinical variables would be useful in the early evaluation of CPAP therapy.

Methods

Study sample

According to the guideline of OSAS diagnosis and therapy,Citation17 newly diagnosed OSAS patients who met the criteria of CPAP therapy (apnea/hypopnea index [AHI] ≥15 or AHI <15 with complications) were consecutively recruited from March to August 2013 at the Sleep Center of The First People’s Hospital of Yunnan Province and the Department of Respiratory Medicine of The Second Affiliated Hospital of Kunming Medical University. The patients with severe diseases or the patients who did not start nasal continuous positive airway pressure (nCPAP) therapy within 30 days after titration trial at the sleep center were excluded.

Sleep test

The diagnostic polysomnography (Alice 5; Respironics, Murrysville, PA, USA) included electroencephalography, electrooculography, chin electromyography, airflow at the nose and mouth, abdominal and chest movements, electrocardiography, sleep position and snoring frequency. An apneic episode was defined as a complete cessation of airflow or reduction in airflow by >90% of the baseline for at least 10 seconds; a hypopneic episode was defined as a reduction in airflow by >30% of the baseline for at least 10 seconds in association with a fall in arterial oxygen saturation of at least 4% or 50% of the baseline for at least 10 seconds in association with a fall in arterial oxygen saturation of at least 3%.Citation17 A titration trail would be conducted after sleep study, if the person met the criteria of taking CPAP therapy.Citation17

Data collection

Demographic data, height, weight, circumferences of neck, waist and hip of each subject were recorded at the beginning and the end of the study at hospitals. Subjective daytime sleepiness, fatigue, depression and sleep quality were measured using the ESSCitation18 (0–24, higher score indicated sleepier), Fatigue Severity Scale (FSS, 9–63, higher score indicated more fatigue),Citation19 Zung’s Self-Rating Depression Scale (SDS, 20–80, higher score indicated more depressed)Citation20 and The Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI, 0–21, higher score indicated lower sleep quality)Citation21 before the onset of therapy and at the end of 3rd, 6th, 9th and 12th week of therapy from the date of starting nCPAP therapy. After the patient had started nCPAP therapy, the well-trained research team members made appropriate appointments and then interviewed these patients via telephone at the end of 3rd, 6th and 9th week of therapy. The first and last interviews took place at hospital before sleep studies. Use of nCPAP was recorded by a memory card in the nCPAP, which stored the daily information on the times at pressure. Subjects were recommended to bring the nCPAP to the clinics to download the records at the end of the 12th week.

The protocol of this study was approved by the ethics committees of Prince of Songkla University and The Second Affiliated Hospital of Kunming Medical University. Written informed consent was obtained from all eligible participants.

Data analysis

ESS, FSS, SDS and PSQI scores were initially compared with 3-week-average nightly adherence hours using scatter plots and Spearman correlation coefficients. For convenience in subsequent analysis, average adherence was cut into 3 ranges: <4 hours, 4–6 hours and ≥6 hours. Four scores were compared across the 3 adherence ranges at each time using one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) and F-test. Where the F-test was significant, pairwise comparisons were tested using two-sample t-test. Comparisons across therapy phases were made and tested by fitting mixed-effects random-intercept linear regression models in which adherence range and therapy phase and their interaction were fitted. This was necessary because the patient composition in any one adherence range changed from phase to phase.

As measurements were taken for each patient on 5 occasions (at baseline, 3rd, 6th, 9th and 12th week of therapy), the relationships of adherence, therapy phase and baseline variables with outcome parameters were modeled using mixed-effects random-intercept linear regression models in which the need for fitting an interaction between adherence range and therapy phase was explored. Mixed-effects regression was used to identify the effect of adherence level on ESS, FSS, SDS and PSQI. Adherence level, therapy phase and their interaction and other potential influencing factors were initially included in the models and considered to act as fixed-effect variables, whereas patients’ common variable (the order of patient recruited in this study) was considered to be the random-effect variable. The covariance structure of mixed-effect model enables investigation of the assumption of equal variance for random effects. Manual backward exclusion method was used to refine the models, the variables without significant contribution to the fit of model being removed sequentially according to log-restricted maximum likelihood values. All the significance tests were 2-sided, and P-values <0.05 were considered as indicating statistical significance.

Results

In this study, 80 newly diagnosed OSAS patients were recruited and 76 patients completed a 12-week follow-up. Among 76 patients, over three quarter of them were middle-aged males, and most of them were office workers. At the baseline, the mean values of body mass index (BMI) and waist-and-hip-ratio were approximately 27 kg/m2 and 1, respectively (). The overall mean of the average duration of nightly use of nCPAP during 12 weeks was 5.60±1.99 hours.

Table 1 Demographic and relative clinical information of 76 OSAS patients at baseline

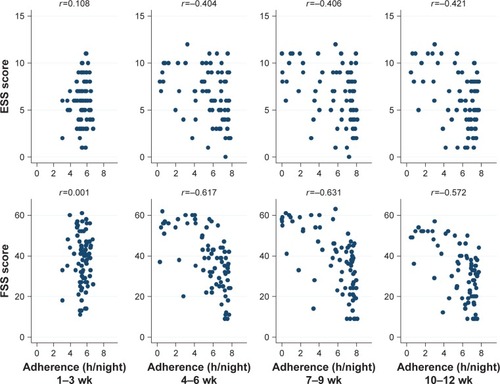

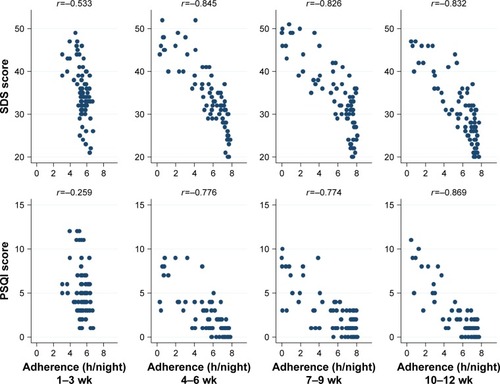

shows the crude relationship between adherence and ESS and FSS scores in each 3-week period. After first 3-week therapy, the lower adherence was related to greater concurrent sleepiness and more fatigue. As shown in , with the progress of therapy, the good adherence correlated with low SDS scores, meanwhile the poor adherence correlated with high SDS scores. Similar relationship was also observed for the PSQI scores (). These relationships were evident from the second 3-week period onward.

Figure 1 The crude relationship between adherence and ESS and FSS scores in each 3-week period.

Abbreviations: h, hour; wk, weeks.

Figure 2 The crude relationship between adherence and SDS and PSQI scores in each 3-week period.

Abbreviations: h, hour; wk, weeks.

Subsequent analysis was based on the adherence cut into 3 ranges: <4 hours, 4–6 hours and ≥6 hours. shows the distributions of adherence levels in each of the fourth 3-week therapy. During the first 3 weeks of therapy, ~8% of the patients used nCPAP for <4 hours per night (mean [SD], 3.57 [0.41]), while ~17% of the patients used nCPAP ≥6 hours per night (6.37 [0.20]), and three quarter patients used it 4–6 hours per night (5.44 [0.38]). However, the proportion of adherence of 4–6 hours per night decreased through subsequent therapy phases. This was demonstrated by an increase in patients using nCPAP <4 hours and an increase in patients using it for ≥6 hours. After the first 3-week therapy, over 50% of the patients in each 3-week period used nCPAP ≥6 hours.

Table 2 Distributions of adherence levels at each therapy phase (N=76 in each therapy phase)

shows ESS, FSS, SDS and PSQI scores throughout the 3-month nCPAP therapy. During first therapy phase, ESS score rapidly reduced from a mean of 12.6 at baseline to between 5 and 6 in all adherence levels, and there were no significant differences among 3 adherence levels. However, with the progression of therapy, the adherence levels showed significantly different effects on ESS score. After first therapy phase, adherence ≥6 hours level maintained the efficacy of first therapy phase, but <4 hours level was associated with increase in ESS score at the second therapy phase, which was maintained at 8–9. The lack of statistical significance in the ESS score at <4 hours level over the therapy phases was a result of the different patient compositions in this adherence range, with additional patients occupying this adherence range after the 3rd week. However, the beneficial effect of increased adherence was evident from the second 3-week period onward ().

Table 3 Distributions of ESS, FSS, SDS and PSQI scores across adherence levels through 12-week nCPAP therapy

A similar pattern of FSS score and adherence was seen over the fourth 3-week periods. However, the FSS became significantly reduced over time in the ≥4 hours adherence patients and was significant in the 4–6 adherence patients only at the last therapy phase, whereas the ≥6 hours adherence patients showed a steady improvement throughout. Through the 4 therapy phases, the FSS scores of <4 hours adherence patients consistently had higher FSS scores than the patients with better adherence ().

The distributions of SDS score over the fourth 3-week period were consistent with FSS score. The SDS scores across 3 adherence ranges differed significantly from each other in each of the 4 therapy phases. The ≥6 hours adherence patients had a steadily reduced SDS over time, while patients adhering for <4 hours or 4–6 hours group had a significantly reduced score only at the 10- to 12-week phase ().

After first 3-week therapy, PSQI scores significantly reduced in all 3 adherence ranges, and the reduced scores were maintained through to the end of the 12th week. However, from the 2nd phase on, the reduction was significantly greater with greater adherence hours ().

In multivariate modeling, the potential influence predictors on ESS, FSS, SDS and PSQI initially included in mixed-effects models were age, sex, BMI, AHI, adherence levels, therapy phases and the interaction between adherence level and therapy phase. Variables not showing significant contribution to the fit of the model were removed. To obtain an adjusted relationship between adherence range and the change in score from baseline for each scale, the initial influencing continuous variables, age, BMI and AHI were managed as the distance from mean, for example, agecen = age − mean of age.

ESS score

As shown in , after model refinement, adherence level, therapy phase and BMI remained. The final model shows that nCPAP therapy could effectively reduce ESS score even at <4 hours adherence level; and with the increase in adherence levels, further reduction in ESS score could be achieved.

Table 4 Mixed-effects models of influencing factors of ESS, FSS, SDS and PSQI scores during 3-month nCPAP therapy

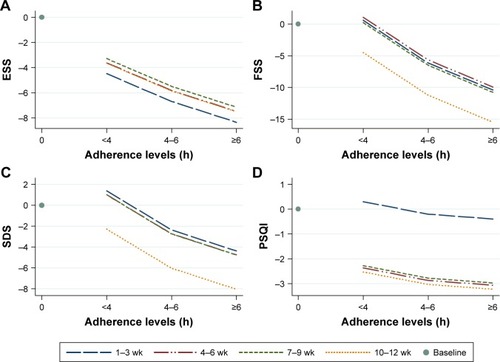

shows the adjusted relationship between the change from baseline of ESS score and adherence levels at each 3-week period. Controlling for BMI, the ESS scores decreased slightly with the increase in adherence, and this relationship was stable throughout the 4th to 12th week of therapy.

Figure 3 Adjusted relationships between adherence range and the changes in ESS, FSS, SDS and PQSI scores from baseline within each 3-week period during first 3 months of nCPAP therapy.

Abbreviations: nCPAP, nasal continuous positive airway pressure; h, hours; wk, weeks.

FSS score

The final mixed-effects model showed that FSS score was influenced by adherence range and therapy phase. Unlike the ESS score, the lowest adherence range showed a nonsignificant effect on decreasing FSS score, but with the increase in adherence ranges, the FSS score improved significantly. Also different from the trend of ESS score in therapy phases, the FSS score decreased significantly at 10- to 12-week therapy phase, compared with the first 3-week therapy phase (). No other factors were identified as being significantly associated with FSS score.

shows the relationship between the change in FSS score from baseline and adherence range, which was stratified by therapy phases. With the increase in adherence range, the FSS score decreased. The most significant improvement was at 10- to 12-week therapy.

SDS score

shows the result of refined model. SDS score was influenced by adherence range, therapy phase, age and sex. The nCPAP therapy could significantly reduce SDS score with ≥4 hours adherence and the effects enhanced with the increasing adherence. The multivariate model also revealed a significantly reduced SDS score at the last therapy phase. Female sex and increasing age correlated with higher SDS scores.

shows the adjusted relationship between adherence range and the change in SDS scores from baseline in 4 therapy phases in males adjusted for age. The lines in the figure of females would be parallel ~3.6 units higher () compared with the figure of males. The SDS scores slightly decreased with the increasing adherence, but a significant drop from baseline occurred at the last therapy phase (10–12 weeks).

PSQI score

shows that adherence range, therapy phase and sex influenced PSQI score. Different from ESS scores, PSQI score did not show a significant decrease unless the adherence was ≥4 hours per night. Controlling for adherence range, therapy phase was an independent factor that significantly decreased PSQI score compared with the first 3-week therapy. Worse sleep quality occurred in females.

shows the adjusted relationship between adherence range and the change in PSQI score from baseline at each therapy phase in males. The lines in the figure of females would be parallel 2.2 units higher () compared with the figure of males. The extent of reduction in PSQI score at 4–6 hours adherence was greater than that at <4 hours; however, adherence of ≥6 hours did not show a further benefit. The effect of therapy phase was significantly different from first to second 3-week period. No more benefit was seen after the 6th week.

Discussion

In this study, the mixed-effect models revealed the independent effect of adherence range, <4 hours, 4–6 hours and ≥6 hours per night using nCPAP, on day- and nighttime symptoms. Even <4 hours adherence could improve ESS score significantly. The significant improvement in FSS and SDS scores required a higher adherence (≥4 hours) than that of ESS score. With increasing adherence, more benefit could be achieved in ESS, FSS and SDS. Compared with the effect of adherence on daytime symptoms, the improvement in nighttime symptom, in terms of PSQI score, was mainly influenced by the progress of therapy phases.

The effect of adherence to nCPAP therapy on daytime sleepiness has been studied, especially the relationship between adherence levels and normalization of ESS score.Citation10,Citation11,Citation15,Citation22–Citation25 Two important studies had been reported by Weaver et alCitation11 and Antic et al,Citation10 which demonstrated that using CPAP ≥4 hours per night could normalize 60%–70% of EDS patients’ ESS score after 3-month therapy. Compared with previous studiesCitation10,Citation11 that categorized ESS score into normal or abnormal, in this study we focused on the relationship between average adherence at each 3-week period and the exact ESS score measured at the end of each 3-week period. Despite the different types of ESS data between previous studiesCitation10,Citation11 and the current study, a similar relationship was found that with the increase in adherence, the patients obtained significant further improvement in ESS score. Moreover, the interaction between adherence ranges and therapy phases was nonsignificant in this study, which suggested that this relationship was stable through the therapy phase.

In this study, after the first therapy phase, the mean of ESS score among OSAS patients (mean [SD], 5.85 [2.43]) was close to the result of local 3085 university teachers and staff population (5.14 [3.78]),Citation26 which indicated that the ESS score of OSAS patients achieved an average level of community population. After that, patients had to take therapy continually to maintain this therapy result in the subsequent phases. To maintain the therapy result of first 3 weeks, patients need to retain the adherence to nCPAP therapy at least >4 hours per night to overcome the increasing trend of ESS caused by OSAS; this result also supported the definition of adherence in previous studies.Citation10,Citation11,Citation15,Citation22–Citation25

Fatigue as a frequent complaint in OSAS patientsCitation7,Citation27–Citation32 has been studied in the recent decade.Citation30,Citation33–Citation35 In this study, we found that the most significant improvement in FSS score was at 10- to 12-week therapy phase, which was in agreement with the previous study.Citation13 In contrast, ESS score improved most notably at the 3rd week therapy. If fatigue was mostly caused by unrefreshing fragmented sleep, the FSS score and ESS score might be expected to have similar timing of improvement. Therefore, the causation of fatigue and daytime sleepiness might be not identical in OSAS patients. However, we found that the most improvement in SDS and FSS scores was at the same therapy phase, which was between 9th and 12th week of therapy. This is consistent with the report that depression was one cause of fatigue.Citation36 Moreover, Mills et alCitation37 reported that the collapse of upper airway could increase not only local inflammation but also systemic inflammation. Fatigue as one of the results of inflammation,Citation38 the FSS score also might be influenced by the local and/or systemic inflammation; and a systemic review indicated that the significant improvement in systematic inflammation needed at least 3 months adequate (≥4 hours per night) CPAP therapy,Citation39 which was potentially consistent with the most significant improvement phase of this study. Therefore, the improvement in fatigue in OSAS patient might require a better adherence and a longer term than daytime sleepiness.

The effect of CPAP therapy on improvement in depression has been studied.Citation8,Citation40–Citation43 However, the effect of CPAP on depression remains controversial.Citation8 In this study, after controlling for age and sex and therapy phase, the adherence level was an independent influencing factor of SDS score, and more improvement in SDS score could be achieved by an increase in adherence. Female sex and aging were also reported as risk factors of depression among OSAS patients by previous study.Citation16 This result might hint the importance of controlling the effect of females and elderly patients in related studies. Another confusion of the effectiveness of nCPAP on SDS was that <4 hours adherence could significantly increase SDS score in the first 9 weeks. One potential explanation was that some OSAS patients’ depression status might not be caused by OSAS, but it might be primary depression coexisting with OSAS. It was also reported that depression was a risk factor of poor adherence to CPAP,Citation14 so that primary depression status might reduce the patients’ level of adherence, and these primary depression patients would obtain limited benefit of nCPAP therapy. Hence, the effectiveness of CPAP therapy on depression status might be underestimated when pooling primary and nonprimary depression patients together.

As mentioned earlier, we observed that the most improvement in SDS score was at 10- to 12-week therapy phase. Because of the few studies designed as multiple measurements of depression with a 3-week interval, we could not compare the effect of therapy phase within 1 study. Nevertheless, some previous studies might support our finding. According to the literature,Citation44 2- to 3-week therapy might not show a specific therapeutic effect on mood symptoms;Citation40,Citation44 4- to 6-week therapy might produce a significant improvement in depression score under the condition of high adherence of therapy (≥6 hours per night);Citation41 8 weeksCitation42,Citation45 or 3 monthsCitation43 could significantly improve depression score with appropriate adherence (>4 hours). Therefore, the timing of evaluation was also important for the assessment of effectiveness of CPAP therapy on depression status.

The significant effectiveness of CPAP therapy on objective sleep quality such as rapid eye movement sleep and arousal has been proved by previous studies;Citation5,Citation46–Citation48 however, the effectiveness on subjective sleep quality has not often been reported.Citation34,Citation49 Previous studies reported that subjective sleep quality of newly diagnosed OSAS patients significantly improved after nCPAP therapy.Citation34,Citation49 This finding was similar to the result of univariate analysis in this study. However, the result of mixed-effect model showed a limited effect of adherence level on the improvements in PSQI score, and the main improvement was caused by the progress of therapy phases. CPAP could significantly improve objective sleep quality; however, using a CPAP device during sleep might lead patients to feel uncomfortable and thus decrease subjective sleep quality despite the correction of apnea. The benefit of improvement in objective sleep quality might improve subjective sleep quality only if the patient was accustomed the sleeping with the CPAP device. This might be partially supported by the results of the above-mentioned 2 long-term studies.Citation34,Citation49

Conclusion

The nCPAP therapy could effectively improve daytime sleepiness in first 3-week therapy phase even the adherence level <4 hours per night. However, the significant improvements in fatigue and depression required a better adherence and longer term. The changes in sleep quality mostly depended on whether the patient was accustomed the sleeping with the nCPAP device. In addition, the mixed-effects models showed the nonsignificance of interaction between adherence level and therapy phase in day- and nighttime symptoms, which suggested that this relationship was stable through the therapy phase.

Limitations of this study

The results of this study were based on a 12-week follow-up, which might limit the ability to generalize from our results to long-term effect of adherence on the abovementioned clinical symptoms. This study repeated 5 times the measurements among 76 OSAS patients. According to the study design, the sample size could meet the sufficient power of univariate analysis; however, for the multiple analysis, it was related to the lack of statistical power.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by the Yunnan Provincial young and middle-aged academic leaders reserve talent program (2011CZ048), National Natural Science Foundation of China (81460017 and 81660019) and the scientific research program of Yunnan Education Department (2017zzx198).

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interests in this work.

References

- GuilleminaultCTilkianADementWCThe sleep apnea syndromesAnnu Rev Med197627465484180875

- American Academy of Sleep MedicineInternational Classification of Sleep Disorders, Revised: Diagnostic and Coding ManualChicago, ILAmerican Academy of Sleep Medicine2001

- RouxFHilbertJContinuous positive airway pressure: new generationsClin Chest Med200324231534212800787

- WeaverTEAdherence to continuous positive airway pressure treatment and functional status in adult obstructive sleep apneaPackAISleep Apnea Pathogenesis Diagnosis and TreatmentNew York, NYMarcel Dekker2002523554

- McArdleNDouglasNJEffect of continuous positive airway pressure on sleep architecture in the sleep apnea-hypopnea syndrome: a randomized controlled trialAm J Respir Crit Care Med20011648 pt 11459146311704596

- SaunamakiTHimanenSLPoloOJehkonenMExecutive dysfunction in patients with obstructive sleep apnea syndromeEur Neurol200962423724219672077

- TomfohrLMAncoli-IsraelSLoredoJSDimsdaleJEEffects of continuous positive airway pressure on fatigue and sleepiness in patients with obstructive sleep apnea: data from a randomized controlled trialSleep201134112112621203367

- PovitzMBoloCEHeitmanSJTsaiWHWangJJamesMTEffect of treatment of obstructive sleep apnea on depressive symptoms: systematic review and meta-analysisPLoS Med20141111e100176225423175

- WangYGeaterAFChaiYPre- and in-therapy predictive score models of adult OSAS patients with poor adherence pattern on nCPAP therapyPatient Prefer Adherence2015971572326064041

- AnticNACatchesidePBuchanCThe effect of CPAP in normalizing daytime sleepiness, quality of life, and neurocognitive function in patients with moderate to severe OSASleep201134111111921203366

- WeaverTEMaislinGDingesDFRelationship between hours of CPAP use and achieving normal levels of sleepiness and daily functioningSleep200730671171917580592

- WoehrleHGramlAWeinreichGAge- and gender-dependent adherence with continuous positive airway pressure therapySleep Med201112101034103622033117

- PowellEDGayPCOjileJMLitinskiMMalhotraAA pilot study assessing adherence to auto-bilevel following a poor initial encounter with CPAPJ Clin Sleep Med201281434722334808

- LawMNaughtonMHoSRoebuckTDabscheckEDepression may reduce adherence during CPAP titration trialJ Clin Sleep Med201410216316924532999

- SinDDMayersIManGCPawlukLLong-term compliance rates to continuous positive airway pressure in obstructive sleep apnea: a population-based studyChest2002121243043511834653

- GagnadouxFLe VaillantMGoupilFDepressive symptoms before and after long-term CPAP therapy in patients with sleep apneaChest201414551025103124435294

- Chinese Society of Respiratory DiseasesObstructive sleep apnea/hypopnea diagnosis guidelineChin J Tuberc Respir Dis201235912 Chinese

- JohnsMWA new method for measuring daytime sleepiness: the Epworth sleepiness scaleSleep19911465405451798888

- KruppLBLaRoccaNGMuir-NashJSteinbergADThe fatigue severity scale. Application to patients with multiple sclerosis and systemic lupus erythematosusArch Neurol19894610112111232803071

- ZungWWA Self-Rating Depression ScaleArch Gen Psychiatry196512637014221692

- BuysseDJReynoldsCF3rdMonkTHBermanSRKupferDJThe Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index: a new instrument for psychiatric practice and researchPsychiatry Res19892821932132748771

- PepinJLViot-BlancVEscourrouPPrevalence of residual excessive sleepiness in CPAP-treated sleep apnoea patients: the French multicentre studyEur Respir J20093351062106719407048

- SantamariaJIranzoAMa MontserratJde PabloJPersistent sleepiness in CPAP treated obstructive sleep apnea patients: evaluation and treatmentSleep Med Rev200711319520717467312

- MuñozAMayoralasLRBarbéFLong-term effects of CPAP on daytime functioning in patients with sleep apnoea syndromeEur Respir J200015467668110780758

- SforzaEKriegerJDaytime sleepiness after long-term continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) treatment in obstructive sleep apnea syndromeJ Neurol Sci19921101–221261506861

- WangYSunXCaoYLiYPrevalence of excessive daytime sleepiness and associated factors in 3085 university teachers and staffs in KunmingJ Kunming Med Univ20133481318 Chinese

- Le BonOFischlerBHoffmannGHow significant are primary sleep disorders and sleepiness in the chronic fatigue syndrome?Sleep Res Online200032434811382899

- ChervinRDSleepiness, fatigue, tiredness, and lack of energy in obstructive sleep apneaChest2000118237237910936127

- OhayonMMShapiroCMSleep and fatigueSemin Clin Neuropsychiatry200051565710704538

- DiasRAHardinKARoseHAgiusMAAppersonMLBrassSDSleepiness, fatigue, and risk of obstructive sleep apnea using the STOP-BANG questionnaire in multiple sclerosis: a pilot studySleep Breath20121641255126522270686

- JacksonMLStoughCHowardMESpongJDowneyLAThompsonBThe contribution of fatigue and sleepiness to depression in patients attending the sleep laboratory for evaluation of obstructive sleep apneaSleep Breath201115343944520446116

- BardwellWAAncoli-IsraelSDimsdaleJEComparison of the effects of depressive symptoms and apnea severity on fatigue in patients with obstructive sleep apnea: a replication studyJ Affect Disord2007971–318118616872682

- ChotinaiwattarakulWO’BrienLMFanLChervinRDFatigue, tiredness, and lack of energy improve with treatment for OSAJ Clin Sleep Med20095322222719960642

- BartlettDWongKRichardsDIncreasing adherence to obstructive sleep apnea treatment with a group social cognitive therapy treatment intervention: a randomized trialSleep201336111647165424179297

- VeauthierCGaedeGRadbruchHGottschalkSWerneckeKDPaulFTreatment of sleep disorders may improve fatigue in multiple sclerosisClin Neurol Neurosurg201311591826183023764040

- SaltielPFSilversheinDIMajor depressive disorder: mechanism-based prescribing for personalized medicineNeuropsychiatr Dis Treat20151187588825848287

- MillsPJDimsdaleJESleep apnea: a model for studying cytokines, sleep, and sleep disruptionBrain Behav Immun200418429830315157946

- DantzerRCapuronLIrwinMRIdentification and treatment of symptoms associated with inflammation in medically ill patientsPsychoneuroendocrinology2008331182918061362

- XieXPanLRenDDuCGuoYEffects of continuous positive airway pressure therapy on systemic inflammation in obstructive sleep apnea: a meta-analysisSleep Med201314111139115024054505

- HaenselANormanDNatarajanLBardwellWAAncoli-IsraelSDimsdaleJEEffect of a 2 week CPAP treatment on mood states in patients with obstructive sleep apnea: a double-blind trialSleep Breath200711423924417503102

- SchwartzDJKohlerWCKaratinosGSymptoms of depression in individuals with obstructive sleep apnea may be amenable to treatment with continuous positive airway pressureChest200512831304130916162722

- KawaharaSAkashibaTAkahoshiTHorieTNasal CPAP improves the quality of life and lessens the depressive symptoms in patients with obstructive sleep apnea syndromeIntern Med200544542242715942087

- EdwardsCMukherjeeSSimpsonLPalmerLJAlmeidaOPHillmanDRDepressive symptoms before and after treatment of obstructive sleep apnea in men and womenJ Clin Sleep Med20151191029103825902824

- LeeISBardwellWAncoli-IsraelSLoredoJSDimsdaleJEEffect of three weeks of continuous positive airway pressure treatment on mood in patients with obstructive sleep apnoea: a randomized placebo-controlled studySleep Med201213216116622172966

- HabukawaMUchimuraNKakumaTEffect of CPAP treatment on residual depressive symptoms in patients with major depression and coexisting sleep apnea: Contribution of daytime sleepiness to residual depressive symptomsSleep Med201011655255720488748

- LoredoJSAncoli-IsraelSDimsdaleJEEffect of continuous positive airway pressure vs placebo continuous positive airway pressure on sleep quality in obstructive sleep apneaChest199911661545154910593774

- LoredoJSAncoli-IsraelSKimEJLimWJDimsdaleJEEffect of continuous positive airway pressure versus supplemental oxygen on sleep quality in obstructive sleep apnea: a placebo-CPAP-controlled studySleep200629456457116676791

- HsuCCWuJHChiuHCLinCMEvaluating the sleep quality of obstructive sleep apnea patients after continuous positive airway pressure treatmentComput Biol Med201343787087823746729

- MermigkisCBouloukakiIAntoniouKObstructive sleep apnea should be treated in patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosisSleep Breath201519138539125028171