?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.Abstract

Objectives

Adherence to multiple sclerosis (MS) treatment is essential to optimize the likelihood of full treatment effect. This prospective, observational, single-center cohort study investigated adherence to fingolimod over the 2 years following treatment initiation. Two facets of adherence – implementation and persistence – were examined and compared between new and experienced users of disease-modifying treatments (DMTs).

Materials and methods

Implementation rates were based on the proportion of days covered and calculated as percentages per half-yearly visits and over 2 years, captured through refill data, pill count, and self-report. Nonadherence was defined as taking less than 85.8% of prescribed pills. Implementation rates were classified as nonadherent (<85.8%), suboptimally adherent (≥85.8% but <96.2%), and optimally adherent (≥96.2%), including perfectly adherent (100%). Persistence, ie, time until discontinuation, was analyzed by Kaplan–Meier analysis. Reasons for discontinuation were recorded.

Results

The cohort included 98 patients with relapsing MS, all of whom received a dedicated education session about their medication. Of these 80% were women, 31.6% had fingolimod as first DMT, and 68.4% had switched from other DMTs. The mean implementation rate over 2 years was 98.6% (IQR1–3 98.51%–98.7%) and did not change significantly over time; 89% of measurements were in the optimally adherent category, 45.6% in the perfectly adherent category. There was one single occurrence of nonadherence. New users of DMTs were 1.29 times more likely to be adherent than experienced users (OR 1.29, 95% CI 1.11–1.51; P<0.001), but not more persistent. Nineteen of 98 patients discontinued fingolimod.

Conclusion

The very high implementation rates displayed in this sample of MS patients suggest that facilitation by health care professionals in preserving adherence behavior may be sufficient for the majority of patients. Targeted interventions should focus on patients who are nonadherent or who stop treatment without intention to reinitiate.

Introduction

Multiple sclerosis (MS) is a chronic, inflammatory-mediated, and secondary neurodegenerative disease of the central nervous system with an unpredictable and potentially disabling course.Citation1 In Switzerland, around 10,000 persons are affected by MS.Citation2 Disease-modifying treatments (DMTs) – which can be either injectable (iDMTs), oral (oDMTs), or intravenous (ivDMTs) – reduce relapse rates and slow disease progression.Citation1,Citation3 Fingolimod (Gilenya®; Novartis, Basel, Switzerland) was the first oDMT, approved in Switzerland as first-line treatment in 2011.Citation4

Adherence to MS treatment is important to achieve the full benefit of DMT. Several studies have shown that missing doses are associated with more relapses, greater health-resource use, and higher health care costs.Citation5–Citation14 Similarly, nonpersistence has been shown to be associated with more inpatient admissions and emergency-room visits.Citation13 According to the World Health Organization, adherence is

the extent to which a person’s behavior – taking a medication, following a diet, and/or executing lifestyle changes – corresponds with agreed recommendations from a health care provider.Citation15

The International Society for Pharmacoeconomics and Outcomes Research (ISPOR) Medication Compliance and Persistence Special Interest Group recommends the term “medication compliance” for medication-taking behavior, or interchangeably the term “adherence”.Citation16 The European Ascertaining Barriers to Compliance (ABC) project team advocates the term “adherence to medications” as an overall term, which is further differentiated into the three components of “initiation”, “implementation”, and “discontinuation”.Citation17 Implementation is the term to describe those aspects of medication-taking with regard to frequency, dosage, and timing, and the ISPOR and ABC conceptualizations of adherence differ in this respect. Both groups agree on the definition of persistence as the length of time from the first to the last dose of a medication. Specific to MS, in 2014 the Adherence in Multiple Sclerosis (ADAMS) consensus group recommended the term “adherence” instead of “compliance” to avoid the latter’s implication of paternalism.Citation18

Adherence to fingolimod treatment is important, since periods of treatment interruption followed by unmonitored reinitiation can result in unsupervised first-dose adverse cardiac events. Implementation of fingolimod has been examined in six retrospective previous studies.Citation19–Citation22 Agashivala et al found patients with fingolimod to be significantly more adherent than patients with iDMTs. Patients treated with fingolimod had a medication-possession ratio (MPR) of 0.9 and proportion of days covered ratio of 0.8 over 1 year.Citation19 Bergvall et al found a lower risk of being nonadherent over 1 year among fingolimod users compared to users of iDMTs.Citation20 In contrast, Higuera et al found that patients with oDMTs were not more likely to be adherent than patients with iDMTs, which have flu-like symptoms as the main side effect.Citation21 Likewise, Burks et al did not find a difference in implementation between oDMT and iDMT users.Citation5 In contrast, users of iDMTs showed a significantly higher mean MPR than oDMT users in a study by Munsell et al (mean MPR 0.69 vs 0.68, P=0.0002), whereas the proportion of adherent patients (MPR ≥0.8) did not differ significantly between the groups. The route of administration – oDMT or iDMT – was not a significant predictor of adherence.Citation22 In a study comparing oDMTs, ie fingolimod, dimethyl fumarate (Tecfidera®; Biogen, Cambridge, MA, USA), and teriflunomide (Aubagio®; Sanofi Genzyme, Cambridge, MA, USA), over 1 year, patients taking fingolimod were more adherent than patients taking other oDMTs regarding both implementation and persistence.Citation23

In this study, which adopted largely the ABC framework for adherence, we aimed to investigate long-term implementation of oral fingolimod prospectively in a clinical and investigator-initiated setting. The primary objective was to measure implementation of fingolimod over the 2 years following treatment initiation. Secondary objectives were to evaluate changes in implementation rates in nonadherent patients after participation in an adherence-support program, differences in implementation between new and experienced users of DMTs, and persistence over the 2 years following treatment initiation. A fourth secondary objective concerned the effects of a patient-education program delivered at treatment start. These findings have been reported elsewhere.Citation24

Materials and methods

Study design, subjects, and setting

This investigator-initiated, prospective, observational, single-center, nurse-led cohort study was performed at the MS Center of the University Hospital Basel (Basel, Switzerland). Between June 2012 and September 2014, all patients initiating fingolimod at the center were screened for eligibility. Eligible were patients with relapsing MS who were at least 18 years old and spoke sufficient German to understand the informed-consent form. Excluded were patients referred by external neurologists and those unable to provide consent. Also excluded were patients with protocol-defined moderate–severe cognitive deficits. Patients who declined to participate were asked if they were willing to give the same demographic data as participants and their reason for nonparticipation.

Data collection

Implementation was measured every 6 months over 2 years, ie, at months 6, 12, 18, and 24, until August 2016. Study data were collected in meetings of 5–10 minutes before or after the regular consultation with the neurologist; study visits did not require separate appointments. A few days before the visit, participants were reminded to bring their current fingolimod package to the visit.

Implementation data were captured in a standardized way in a procedure called minimal-adherence intervention, which was implemented by the nurses who performed the study. The aim was to influence patients in their medication-taking behavior in a predefined and limited way. The following steps of the data-capture procedure are known to have adherence-enhancing effects: participants received immediate feedback about their implementation rates, they were asked to rate the number of capsules missed in the past 6 months, which raised their awareness of possibly missed doses, and as necessary, adherence goal setting for the next 6 months was encouraged. The nurses approached the patients in a nonjudgmental way, eg, by not judging implementation rates, not proposing improvement or goals, and not insisting on changes in how patients arranged their intake. The nurses had been trained for the minimal-adherence intervention by the first author before study start, and mutual observation with feedback on consistency of delivery was performed several times in the study’s first year.

Outcome measures

Implementation rates

Fingolimod is a capsule of 0.5 mg taken once daily. It is available in packages of 28 and 98 capsules. Capsules are arranged in rows of seven, with each day of the week (Monday through Sunday) imprinted alongside each row to assist patients with their daily intake.

Implementation was measured by means of a triangulated method: first, refill data of the past 6 months were retrieved, then a pill count was done during the study visit, and lastly deviations like pills-in-the-pocket were reconciled through patient self-report. Refill data were retrieved before study visits, either from the Swiss umbrella organization of health insurers (SVK) or the pharmacies of the participants. All participants had given written consent for data retrieval. Pill counts were done in the presence of the patient during the study visits based on the current package in use by the patients. In addition, patients were asked about capsules lost or destroyed and about capsules stored at other places (eg, handbags, at vacation homes, at work). Reconciliation of such deviations was done before the pill count and before entry into the Excel-based adherence-calculator. The resulting implementation rate was available immediately and shared with patients.

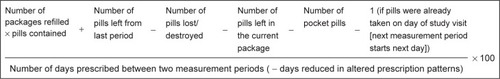

Implementation rates were based on the proportion of days covered.Citation25,Citation26 This was calculated as the percentage of capsules possessed at the beginning of a measurement period minus the number of capsules possessed at the end of a measurement period relative to capsules prescribed, rounded to one decimal place (see for the equation). Additional methodological information is included in the Supplementary material.

Implementation categories

Implementation was divided into four categories: optimally adherent, perfectly adherent, suboptimally adherent, and nonadherent (see ). Optimal implementation was defined as having missed at most seven pills per 183 days, which corresponds to missing at most one capsule per package of 28 capsules (≥96.2% of doses). Suboptimal implementation was defined as missing between more than seven but at most 26 capsules per 183 days. This corresponds to missing between one and four capsules per package, or missing between half and two packages per year (<96.2% but ≥85.8% of doses). Nonadherent implementation was defined as missing more than 26 capsules in 183 days, corresponding to missing more than one capsule per week or around two packages per year. This translates into <85.8% of doses, which is consistent with the cutoff of 85% used by Steinberg et al.Citation11 Perfect implementation was defined by 100% implementation or taking exactly one capsule per day.

Table 1 Definition of adherence (implementation) categories

The cutoff for nonadherence of 85.8%, or missing more than one capsule per week, was defined by querying the center’s nurses and physicians. The widely used cutoff of 80% seemed not strict enough for a pill that has to be taken once daily. However, fingolimod allows some “generosity”: a half-life of 6–9 days and a broad therapeutic window make dosing errors in amount and time quite “forgivable”, and hence staff settled on the 85.8% cutoff.Citation27

Change in implementation rate after an adherence-support program

In cases of nonadherence, participants were offered an adherence-support program of one to three sessions that followed the guidelines of “adherence therapy”, an internationally acknowledged program.Citation28 The implementation rate in the subsequent measurement period was compared to the previous one.

Differences between new and experienced DMT users

Patients who took fingolimod as first DMT were compared in terms of implementation and persistence with patients who switched from other DMTs to fingolimod. In addition, we compared patients who were treated with only iDMTs before switching to fingolimod with those who switched from an ivDMT (excluding three patients who received an iDMT between the ivDMT and fingolimod).

Persistence

Persistence was the length of time that patients took fingolimod from the first dose until study end or until discontinuing fingolimod for an unknown period of time by decision of the patient and/or the neurologist. Reasons for discontinuing fingolimod were recorded. They were grouped into five categories: adverse events leading to contraindication for fingolimod (eg, macular edema), pregnancy (planned or unplanned), lack of efficacy (agreed upon between neurologist and patient), perceived adverse events that made a patient want to stop, and patient wish to stop any treatment.

Statistical methods

The sample size for the study was calculated in advance to allow the estimation of the implementation rate with accuracy precision of a 95% CI of 6%. Based on literature before 2011, it was estimated that 60% of participants would be optimally adherent, 20% suboptimally adherent, and 20% nonadherent. Including a total of 98 patients was estimated to be sufficient to assure 78 evaluable cases at a dropout rate of 20%. Dropout would include nonpersistent patients.

The full-analysis set comprised all participants who signed the informed consent and took at least one capsule of fingolimod. The “at least one follow-up” set included all participants with at least one follow-up visit. All analyses were performed using R version 3.4.0 and using available data only;Citation29 no imputation of missing values was performed.

Continuous patient baseline characteristics, as well as raw implementation rates per visit, were summarized through the mean and first and third quartiles of distribution. Categorical variables were reported as frequency distributions and percentages. We compared groups using the Wilcoxon rank-sum test for continuous and Fisher’s exact test for categorical variables.

Mean implementation rates at each follow-up visit and over 2 years were estimated via logistic regression models with an intercept only. Predicted values with 95% CIs were provided. To compare between groups, a categorical grouping variable was added to the model as a predictor. Summing of all prescribed and taken pills over 2 years was done based on available values; missing visits were ignored. The effect of time on implementation was examined using generalized estimation equations (GEEs) with an unstructured correlation matrix. Implementation rate at each visit was used as outcome, and follow-up time as predictor. Robust standard errors were estimated using the sandwich estimator. As a sensitivity analysis, a GEE with an exchangeable correlation matrix was fitted to the data. Implementation categories were reported per number of participants in each category for each visit and over 2 years. Since only one patient was nonadherent, and in one visit only, the effect of the planned support program for nonadherent patients could not be evaluated.

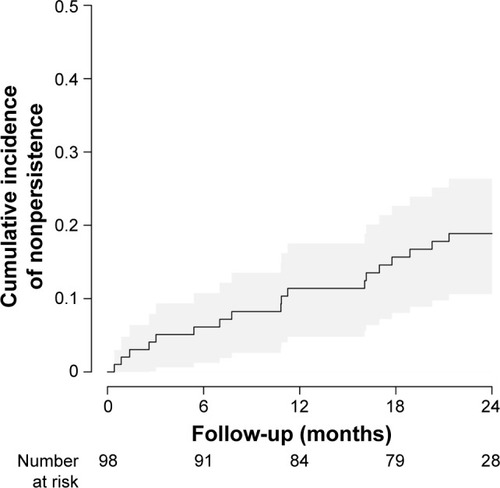

The cumulative incidence of nonpersistence was calculated via Kaplan–Meier estimates and compared between groups using the log-rank test. Participants were censored at the last known day of taking fingolimod or at their last follow-up date. The reasons for discontinuation were summarized in a table.

Ethics statement

Participants gave written consent after treatment initiation and after appropriate time to decide on study participation. The study was approved by the ethics committee of northwestern and central Switzerland (EKNZ).

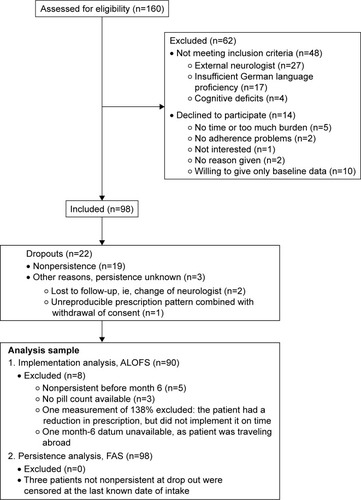

Results

Between June 2012 and September 2014, 160 patients initiated fingolimod at the center, of which 112 were eligible for study participation. Fourteen persons declined to participate, and thus 98 were included in the study (). Participants’ characteristics have been described elsewhere, and are summarized in .Citation24 Almost 80% were women (n=78). The median age was 41 (IQR1–3 31–46) years, ranging 22–71 years. Median time since diagnosis was 4.6 (IQR1–3 1–11.4) years; the minimum was 2 months and the maximum 36.4 years. Fifty-nine percent lived with a partner, 41% lived alone, 40% had a university degree, and all others had polytechnic degrees or vocational training.

Figure 2 Flow diagram of study participation.

Table 2 Demographic and clinical characteristics of study participants (n=98)

Approximately two-thirds of participants (68.4%) had received other MS treatments before and were experienced DMT users, whereas for about a third (31.6%) fingolimod was the first MS treatment. Three-quarters (76%) of the experienced DMT users switched to fingolimod from iDMTs and a quarter (24%) from ivDMTs. All but four previous ivDMT users had used iDMTs as well.

There were no significant differences in patient characteristics between participants and the ten patients who declined to participate but provided demographic data. Self-reported implementation rates during the last month of the previous DMT were not analyzed: none of the nonparticipants had indicated missing a dose, whereas ten participants had indicated having missed between one and 30 doses.

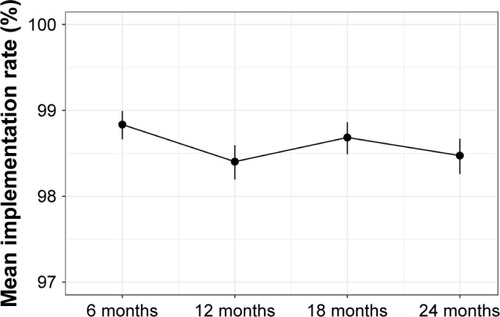

Implementation rates

Implementation was very high, with low variation. The mean estimated implementation rate over 2 years was 98.61%, with a narrow 95% CI (98.51–98.7). The slight variations between the four measurement time points are displayed in and . There was no evidence that implementation rates decreased over time. The GEE with the unstructured correlation matrix analysis showed that implementation rates were lower at all visits following the first visit at month 6 (). For month 12, the reduction was statistically significant, but not strongly so (P=0.041), and when compared to a sensitivity analysis using an exchangeable correlation matrix, statistical significance disappeared (P=0.54).

Table 3 Summary of raw implementation rates and mean estimated implementation rates per visit

Table 4 Implementation rate over time (along visit): categorical and continuous model by GEE with an unstructured matrix

Adherence categories

Of the 329 measurements performed, 88.8% demonstrated optimal adherence and 11% suboptimal adherence, and one single measurement was classified as nonadherence (). Among all measurements showing optimal adherence, 45.6% displayed perfect adherence. Eighteen patients did not miss any capsules over the 2-year study period. Eleven measurements showed more than 100% intake: nine measurements showed one and two measurements showed three excess capsules. No significant differences in patient characteristics were found between optimally adherent and suboptimally adherent participants.

Table 5 Distribution of adherence (implementation) categories

Effectiveness of a support program for nonadherent participants

The single patient who was nonadherent at month 12 (minus 27 capsules) accepted a phone call by the first author. At the next visit, the patient had missed distinctly fewer pills (eight). There were three patient measurements near the nonadherence threshold: 85.9%, 87.2%, and 87%.

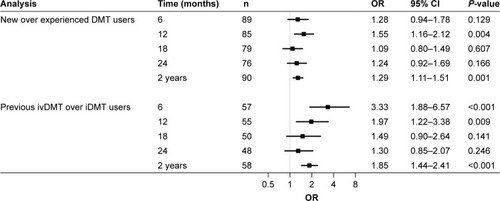

Comparison of implementation between new and experienced users of DMTs

Implementation rates of new DMT users were generally higher than those of experienced users, and this was consistent across all time points. ORs were significant for month 12 and the whole study period. Overall, new users were 1.29 times more likely to take a prescribed capsule than experienced users (OR 1.29, 95% CI 1.11–1.51; P<0.001) (). All new DMT users, except for two, were newly diagnosed MS patients. In contrast, no significant differences were found between the two user groups with regard to persistence.

Figure 4 ORs for taking a designated capsule: two subgroup analyses.

In patients previously treated with DMTs, those prescribed ivDMTs (natalizumab [Tysabri®; Biogen] or mitoxantrone [Novantron®; Meda Pharma GmbH, Wangen-Brütisellen, Switzerland]) showed a higher probability of taking a pill compared to those prescribed iDMTs (IFNβ-1b [Betaferon®; Bayer AG, Leverkusen, Germany], IFNβ-1a subcutaneously [Rebif®; Merck KGaA, Darmstadt, Germany] and intramuscularly [Avonex®; Biogen], and glatiramer acetate [Copaxone®; Teva Pharmaceuticals Ltd, Petach Tikva, Israel]), resulting in higher implementation rates (). The difference was the greatest in the first 6 (OR 3.33, 95% CI 1.88–6.57; P<0.001) and 12 months (OR 1.97, 95% CI 1.22–3.38; P=0.009). With time, the difference between ivDMT and iDMT users diminished, and at 18 months was no longer significant. Over 2 years, ivDMT users were 1.85 (95% CI 1.44–2.41) times more likely to take a prescribed pill than iDMT users (P<0.001). Because of the small number of patients and the multiple testing, these results should be interpreted with caution. Similarly, the varying number of patients in each model makes comparisons across time points difficult, though the trend seems stable.

Persistence

Altogether, 19 participants (19.4%) discontinued fingolimod in the 2 years following treatment initiation. Seven patients discontinued in the first 6-month interval, followed by three in months 7–12, five in months 13–18, and four in months 19–24. An additional three participants dropped out and were lost to follow-up, and it is unknown whether or not they continued fingolimod. The cumulative incidence of nonpersistence with time, displayed as Kaplan–Meier estimates, is shown in .

Figure 5 Cumulative incidence of nonpersistence.

Nonpersistence was relatively stable over time. Reasons for discontinuation are summarized in . Of the 19 participants who discontinued fingolimod, eight switched directly to an alternative therapy, five interrupted treatment for pregnancy, and six stopped treatment without immediate intention to initiate an alternative treatment. Post hoc analysis showed that all except for one initiated alternative treatment at a later time.

Table 6 Reasons for nonpersistence with fingolimod by category (n=19)

Dropouts

Numbers and reasons for dropout are displayed in . Two patients attended the first visit, but did not bring their packages. They stated they were willing to send a photo of their packages, but they did not do so, despite several attempts at contact by the nurses. Neither patient showed up for the month-12 neurological consultation or study visits. After several more attempts at contact, they were registered as dropouts. Their pharmacy-refill data revealed that they were still persistent at month 6, but had stopped buying fingolimod before month 12. Their refill pattern also revealed that between months 6 and 12 they lacked 29 and 41 capsules, respectively, to cover all prescribed days. Therefore, both participants were nonadherent and nonpersistent. See also the Supplementary material for additional results.

Discussion

Implementation rates showed very high results at a mean of 98.6% over 2 years, with 88.8% of measurements determined as optimally adherent and 45.6% perfectly adherent. A quarter of persistent patients did not miss a single capsule in 2 years. Nonadherence – at a cutoff of 85.8% – was observed in only a single case. Implementation rates did not change significantly over time. Nineteen percent of patients discontinued treatment with fingolimod during 2 years after treatment initiation. New DMT users were significantly more adherent than experienced users, but not more persistent.

Implementation

High mean adherence rates ≥90% and high percentages of adherent patients at cutoffs of 80% and 90% have been reported in other recent long-term studies on MS DMTs.Citation6,Citation7,Citation13,Citation30–Citation35 In five studies, implementation was assessed by means of electronically recorded real-time administration data (RebiSmart®).Citation7,Citation30,Citation32,Citation34,Citation35 Two studies captured implementation on the basis of monthly self-reports, which is likely to have increased adherence by decreasing forgetfulness, the main reason for suboptimal implementation.Citation6,Citation33 Five studies were retrospective,Citation7,Citation13,Citation32,Citation34,Citation35 while four were prospective.Citation6,Citation30,Citation31,Citation33 In two studies, nurses or pharmacists provided some form of patient-adherence support.Citation6,Citation31 In contrast, we measured adherence at 6-month intervals without electronic methods, and apart from the support at the start of treatment, without specific nurse support.

Since our study was not a randomized trial and did not include a control group, one can only speculate as to why implementation rates were so high. Among possible reasons are 1) the influence of adherence-enhancing elements, such as the patient-education program at treatment start or the minimal-adherence intervention during study visits; 2) the drug’s tolerability and ease of administration; 3) specific features of the mainly Swiss population and its culturally inherent behaviors, such as reliability; 4) a sense of appreciation and responsibility by the patients for a highly expensive treatment provided first-line; or 5) very high intrinsic motivation to be adherent on the part of patients. Alternately, it is also possible that the design of the study may have induced biases.

Previous research supports the assumption that well-informed patients are significantly more adherent than less informed patients.Citation36 Conceivably, academic centers like ours may have better access to evidence-based and up-to-date MS information. In addition, they may also be more likely to offer targeted patient education. However, the limited evidence on whether MS-patient education is better or translates into better adherence in academic vs nonacademic centers may suggest otherwise, and the issue requires further study. Our finding that educational levels did not differ between optimally and suboptimally adherent patients is in line with several studies in the MS population,Citation37–Citation40 whereas in two MS studies patients with university degrees were less likely to be adherent.Citation41,Citation42 While Phillips et al reported higher odds of adherence in patients with full insurance coverage, the high implementation rates in our study were found in spite the fact that patients paid the equivalent of at least US$990 per year out-of-pocket.Citation43

One reason for the observed high adherence rates may have been the measurement methods. It is remarkable that in MS adherence research, the highest implementation rates have tended to be reported in studies using an electronic monitoring method (RebiSmart), though Medication Event Monitoring Systems (MEMS) are known to yield lower implementation rates than other methods.Citation37,Citation44 A recent scoping review found a significant difference between MEMS and nonelectronic methods in 80% of studies in which different methods were used: self-report overestimated implementation by 17%, pill count by 8%, and ratings by 6%.Citation44 In an MS study, Bruce et al reported that self-reports and diaries overestimated adherence compared to electronic syringe-disposal monitoring.Citation37 Triangulation of different methods has been proposed by other researchers, especially considering that studies comparing different assessment methods have failed to identify one that is clearly superior to other methods.Citation45,Citation46 A such, our choice was to use a triangulation method, aiming for high precision in measuring implementation.

There is a growing trend to use exclusively large databases (eg, refill, payment claims) to perform retrospective studies. While such analyses may be generalizable as to implementation rates, clinical precision is a problem. Prospective studies, on the other hand, are time-consuming and prone to biases as well, and these may lead to higher adherence rates than unobtrusive methods, such as database analyses: 1) Hawthorne effect of behaving differently when being observed, applicable to both study participants and clinicians and researchers; 2) social desirability bias; 3) “white-coat adherence” of resuming highly adherent behavior shortly before a visit; and 4) difficulties in separating diagnostic measurement from intervention. Moreover, nonrandomized prospective adherence studies with voluntary participants are prone to an inherent selection bias, with adherent persons potentially being more likely to participate than nonadherent persons. Our impression of the patients in our study is that their intrinsic motivation was very high and exceeded the potential biases, and that this may explain the high implementation rates.

It is important to reconcile the findings on adherence-implementation rates from our uncontrolled observational study with data from trials on fingolimod, in particular with regard to drug- and disease-specific cutoffs that are clinically meaningful.Citation11,Citation17 In pivotal drug trials, usually neither is efficacy adjusted for adherence nor is the threshold of efficacy loss defined. Further, adherence is generally overestimated in clinical trials, especially in Phase II and Phase III clinical trials performed in ambulatory settings without exact adherence monitoring. Without knowledge of actual adherence, this may lead to an underestimation of (pharmacological) benefits and harms of new drugs.Citation47,Citation48 In the pivotal fingolimod trials, adherence was monitored by pill count. It was assumed that participants would take 100% of their capsules, with a non-adherence margin of 20% accepted. However, there are no validated adherence cutoffs for either fingolimod or other MS DMTs. Retrospective studies based on implementation and relapse data have tried to validate adherence cutoffs, but without much conclusiveness. For instance, Steinberg et al found the risk for relapse to be significantly higher at a cutoff <70% versus 85%.Citation11 For patients on the same iDMT, Cohen et al noted the fewest relapses and the highest proportion of relapse-free patients at a cutoff ≥90%.Citation6 Oleen-Burkey et al found the risk of relapse to decline with increasing adherence: it was significantly lower at an MPR of at least 70% in comparison to lower cutoffs in the 2 years after treatment initiation of glatiramer acetate and even lower at a cutoff of 95%.Citation10 While these results represent a range of potentially adequate implementation rates, the variability does not provide much guidance for clinical practice. Pivotal trials would indeed benefit from drug- and disease-specific thresholds of efficacy loss that are adjusted for adherence and evaluated on the basis of pharmacokinetic properties.

As to measurement methods, clinical trials in MS would benefit from recording adherence electronically,Citation37,Citation47,Citation48 but best if triangulated with other methods. In fact, there seems to be an assumption among clinicians and researchers that perfect adherence is necessary and that any deviation from the prescribed regimen is by definition problematic, whereas a drug’s effectiveness may be achieved with less than 100% adherence. For certain drugs, there may be a (small) drug-or class-specific nonadherence margin to buffer against the occasional missed dose, whereas for other drugs there is virtually no margin. To take life-critical situations as an example, in the organ-transplant setting it has long been known that subclinical noncompliance with immunosuppressive therapy (ie, minor deviations from twice-daily intake of immunosuppressants, as measured by electronic monitoring) has been associated with major graft complications.Citation49,Citation50 In the setting of chronic myeloid leukemia, there is some margin for time deviations from daily intake schedules of imatinib;Citation51 however, there is probabilistically no margin for nonadherence over time without putting cytogenetic and molecular response at risk.Citation52

Therefore, further research is needed to understand why some MS study populations achieve very high adherence rates and others do not. Clinically meaningful cutoffs for the threshold of efficacy loss in MS treatments are required.Citation11,Citation17 Better reporting of adherence-measurement methods has been argued.Citation45,Citation53,Citation54 A debate and coordinated strategy on study designs and measurement methods for MS adherence research would be beneficial, in order to save resources for both researchers and study participants.

An important implication of the high implementation rates observed in our study and perhaps counter to the prevailing beliefs is that investing significant effort in enhancing adherence should not necessarily be promoted intensely at the start of therapy, depending on the population, the standard of care, and the “forgiveness” of a drug. Rather, our study suggests advising most patients to preserve their excellent implementation behavior and to focus instead on the few patients who in fact do have drug-intake problems. This could be achieved by the relatively simple and cost-efficient approaches practiced in our study, eg, talking with patients about organizing drug intake, recognizing facilitating factors and obstacles, pills taken, and pills missed and why. In the process, treatment expectations along with knowledge about MS and beliefs about medicines could be addressed.

In turn, this implies that we should have good methods for detecting and predicting suboptimal implementation. Perhaps surprisingly, in our study the most nonadherent patients did not show up for their appointments. Hancock et al found significant correlations between missed, cancelled, and no-show appointments and poor adherence.Citation55 Therefore, it is recommended to have effective strategies in place for patients who do not show for appointments. Moreover, to date numerous predictors of nonadherence have been identified in MS adherence studies, but no easy-to-use screening tool for predicting suboptimal implementation has been developed, whereas recently a proposition has been presented for identifying patients at risk of nonpersistence.Citation56 Future studies should also consider whether patients’ adherence prior to a DMT switch is predictive of outcome after switching to a further DMT. In this, it will be important to consider the application form (iDMTs, oDMTs, or ivDMTs), that it is not unusual for patients to take a drug holiday around the time of a switch, and that patient recall of prior adherence could be subject to recall bias.

Even if electronic measurement is considered a possible gold standard, “objective control” is not the aim of health care professionals (HCPs) when assessing adherence. Recent qualitative research emphasizes the importance of trust in and a positive relationship with HCPs to adherence.Citation57,Citation58 This elicits other important motivators, like health beliefs, perception of illness control, fear of side effects or disease progression, treatment education, prescriber attitude, and individualized care.Citation57,Citation58 HCPs can facilitate adherence by creating an open space of communication that helps patients to speak about their adherence behavior without being judged or threatened, free of pressure and intrusive advice. HCPs can help patients explore their motivations on treatment and to set individual and realistic implementation goals that are adapted to lifestyle and treatment expectations.

In the present study, implementation was stable over time. This finding is supported by several other recent studies over periods of 1–3 years.Citation7,Citation32,Citation34,Citation35 New users of DMTs, mainly people newly diagnosed with MS, were more likely to be adherent than experienced users. Though speculative, new users may be more motivated, having more hope in a drug’s efficacy and holding less disappointment from prior experiences of lack of efficacy. However, they may also have less realistic expectations, though in our sample both groups had the same educational session on the treatment with fingolimod. Interestingly, previous ivDMT users were more likely to be adherent than those treated only with iDMTs before switching to fingolimod. One possible reason could be that patients with second-line ivDMTs might value treatments more because they have fewer options left than those on first-line treatments. At the same time, they may have experienced better efficacy with natalizumab and mitoxantrone than with injectable treatments and might thus be more motivated to adhere. Alternately, it may also be that better adherence at the beginning of oDMT treatment is triggered by the experience of drug administration under the observation of HCPs.

Persistence

Discontinuation rates of 10% after 1 year and 20% after 2 years are in line with other recent reports of persistence with fingolimod when used as a first-line DMT.Citation59,Citation60 Interestingly, in a German MS center where fingolimod is prescribed as second-line treatment, discontinuation was slightly but not distinctly lower: 5% after 1 year and 15% after 2 years.Citation61 Caution is indicated when interpreting discontinuation rates: nonpersistence with DMTs in MS does not necessarily represent nonadherent behavior. If patients discontinue fingolimod because of macular edema or pregnancy, they demonstrate adherent behavior. Even discontinuing a DMT because of side effects does not need to be considered nonpersistence per se, as long as the patient changes to another treatment. Today’s choice between several DMTs offers the possibility of finding one that works best with regard to efficacy, side effects, and convenience.

From a broader clinical point of view, persistence with treatment implies the time of being treated with one appropriate MS treatment. In MS persistence research, it is useful to distinguish among different forms of persistence behavior and to clearly define each. Truly nonpersistent patients requiring the attention of HCPs are those who stop their treatment by their own decision and do not reinitiate with an alternative treatment. This is the group that could benefit from interventions, though nonpersistence – just like nonadherence – might be the result of a person’s deliberate decision deserving respect and acceptance. Bruce et al developed a telephone counseling intervention to reinitiate DMT for patients who discontinued DMT against medical advice.Citation62

In this study, no difference was found in discontinuation rates between new users of DMTs and experienced users, whereas Fernandez-Fournier et al found a 2.8-fold higher risk of discontinuation for new users of glatiramer acetate than for experienced users.Citation63 Similarly, Esposti et al found the risk of nonpersistence was lower in experienced users of iDMTs than in new users (adjusted OR 0.59, 95% CI 0.43–0.79).Citation64 A possible explanation may lie in the route of administration: for newly diagnosed patients initiating their first MS treatment, it may be more difficult to sustain a treatment by injection than an oral regimen. This is supported by Agashivala et al showing that new users of fingolimod were more likely to be persistent than new users of injectable DMTs.Citation19

Limitations and strengths

The observational nature of this single-center study allows only limited generalizations to other settings. Generalization is limited by the specific drug-education session that our patients received at treatment start. Generalization to other countries is limited by the use of fingolimod as first-line treatment in Switzerland. Implementation behavior might be different in countries with second-line approval. The locus (community versus hospital pharmacy) and the extent of pharmaceutical care provided by the dispensing pharmacist may also influence implementation behavior. Several studies have attested to the important role of the pharmacist in MS care, and this too needs further study. The prospective, uncontrolled design of the study is prone to various biases, and may have overestimated implementation. No clinical measurements were included. Strengths of the study are the careful measurement method and integration into a routine care setting.

Conclusion

The MS population in our study showed stable, high implementation rates over 2 years. Targeted adherence interventions should be reserved for those patients who have difficulty with regular drug intake. For the majority, facilitation by HCPs in preserving patients’ high adherence behavior may suffice, especially for new users of DMTs, who are more likely to be adherent than experienced users. Special attention should be paid to patients not showing up for appointments and to those who stop treatment without intention to reinitiate.

Results

Implementation rates

For all patients missing more than 14 capsules (n=10) per 6 months, refill patterns and self-report did not indicate a treatment interruption of more than 14 days, which would have required reinitiation under first-dose observation.

Fidelity to the protocol and performance integrity

Among all intended implementation measurements of persistent participants, three data sets of the month-6 visit could not be retrieved: one patient was traveling abroad, and two patients did not deliver the information on the number of capsules left in the package. Among 329 visits performed, 90.9% of pill counts were done as intended, ie, with the package present at the visit; 26 were done by photo, one was done by email, and four by telephone. Twelve visits were performed outside the visit window, but were still included into the analysis. Time deviations ranged between 5 days too late and 10 days too early.

Six patients were prescribed dose reductions during one or more measurement periods. The alternative prescribing pattern was either pausing every second or every third day. In five cases, the change was due to lymphocyte counts lower than 0.2×109/L, and in one case due to a degenerative problem of the macula.

Some aspects should be mentioned about fidelity to the minimal-adherence intervention by the nurses performing the study. It is possible that some unintended behavior may have influenced or increased adherence: the nurses acknowledged participants’ implementation achievements a lot. Also, patients often expressed feelings of guilt or shame if they had not taken all pills, and the nurses alleviated these expressions by explaining that missing some pills, eg, “was normal” or “that it would not reduce efficacy”. For ethical reasons, because the adherence study was part of clinical care, addressing adherence was not omitted when deemed appropriate.

Author contributions

AZ designed the study, coordinated its implementation, interpreted the study results, and drafted the manuscript. MC analyzed the statistics and contributed substantially to the interpretation of results. IA and BFD contributed substantially to interpretation of the data and reviewed and revised the manuscript. BFD was involved in the medical care of the patients in the study. All authors contributed toward data analysis, drafting and revising the paper and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Acknowledgments

We are very grateful to the people with MS who participated in the study. We thank Ludwig Kappos for enabling the study at the MS Center Basel. Special thanks are due to the MS nurses and study investigators Suzana Miteva and Karin Wild, who performed the study visits and data-collection procedures. We thank Nancy Wochnik for data control. We also thank all nurses and physicians of the center for supporting the study. A special thanks to Kayal Kündig and her colleagues (SVK) for providing the refill data. We appreciate the help of Nicholas Sanderson in editing the manuscript from the English-language perspective. This investigator-initiated trial was funded by Novartis Pharma Schweiz, who had no role in study design, data collection or analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript. Novartis had the option to review the final version of the article to protect confidential or patentable information. We would like to thank Novartis Pharma Schweiz for funding the study.

Supplementary materials

Materials and methods

Outcome measures

Implementation rates

In addition to the calculation method, capsules lost or destroyed were subtracted from the number of pills possessed. Capsules stored at other places were added to the number of pills left. Medication intake on the day of the study visit, ie, before or after the study visit, was accounted for. Prescription alterations, eg, intake only every second day, were reflected by adapting the denominator to the actual number of days prescribed. The denominator had variable value, because study visits did not take place exactly every 183 days. A visit window of ±3 weeks was allowed.

If participants forgot to bring their package, or if the regular consultation had to be planned outside the study-visit window, participants were asked to send a photo of the package by SMS or email. The rest of the visit was done by phone or email. Exceptionally, information by telephone was accepted, but everything was done to get an “objective” image of the number of capsules left in the package.

No gaps between the first prescription and the first intake had to be considered, as the study started with the first dose taken under observation. Timing of implementation was of no relevance. In the patient-education program at treatment initiation, patients were taught to take the capsule at the same time of the day as much as possible. If they forgot to do so, they might either take it later the same day or omit it until the next day.

As an example of calculating the implementation rate, between the study visits of January 1 and July 1, 2014 (181 days), a patient refills two packages of 98 capsules. In the previous measurement period, 20 capsules had been left in the package. On July 1, the patient has already taken the capsule in the morning and has 33 capsules left in his current package. He keeps two capsules in his work office. One capsule has been squeezed, and he has thrown it away. Therefore, the implementation rate is:

and as such, two capsules were missed.

The study’s simple and easy-to-perform method was chosen because electronic measurement was not feasible at the time the study was designed: electronic smart packages were not available yet, and a MEMS was not affordable. Comparing medication intake with plasma concentration levels was not feasible, due to the lack of a clear correlation (personal communication from the manufacturer).

Dropout

Other reasons than discontinuing fingolimod could lead to study dropout, eg, changing neurologist or if the primary end point – implementation – could not be measured despite the patient continuing to take fingolimod.

Disclosure

AZ has received travel grants for participation in investigator meetings of clinical studies and nurse meetings, and her institution has received consultancy fees for nurse-advisory activities by Actelion, Biogen, Genzyme, Merck Serono, Novartis, Roche, and Sanofi. She has no conflicts of interest relative to the study reported here. MC has no conflicts of interest to declare relative to the study reported here. IA is an equity-holding partner in Matrix45. Matrix45 provides scientific services to pharmaceutical companies on a nonexclusive basis. Employees may not hold equity in sponsor organizations, and may not accept direct payments or other benefits from sponsor organizations. As a faculty member of the University of Arizona, IA has no conflicts of interest to declare relative to the study reported here. BFD received for the institution (University Hospital Basel) advisory board or speaker fees from Biogen, Teva and Novartis, which were used exclusively for research support. BFD received travel support from Novartis, Biogen, and Genzyme. BFD has no conflicts of interests in this work.

References

- CompstonAColesAMultiple sclerosisLancet200837296481502151718970977

- LatzelGSchrobiltgenEFMultiple Sklerose in der Schweiz: Die Lebensbedingungen von MS-Betroffenen und die finanziellen Folgen ihrer Krankheit. [Multiple sclerosis in Switzerland: The living conditions of MS sufferers and the financial consequences of their illness]ZurichSchweizerische MS-Gesellschaft2001 German

- DolatiSBabalooZJadidi-NiaraghFAyromlouHSadreddiniSYousefiMMultiple sclerosis: therapeutic applications of advancing drug delivery systemsBiomed Pharmacother20178634335328011382

- KapposLRadueEWO’ConnorPA placebo-controlled trial of oral fingolimod in relapsing multiple sclerosisN Engl J Med2010362538740120089952

- BurksJMarshallTSYeXAdherence to disease-modifying therapies and its impact on relapse, health resource utilization, and costs among patients with multiple sclerosisClinicoecon Outcomes Res2017925126028496344

- CohenBACoylePKLeistTOleen-BurkeyMASchwartzMZwibelHTherapy optimization in multiple sclerosis: a cohort study of therapy adherence and risk of relapseMult Scler Relat Disord201541758225787057

- SolsonaMDBoquetEMEstruchBCAndresJLImpact of adherence on subcutaneous interferon beta-1a effectiveness administered by Rebismart in patients with multiple sclerosisPatient Prefer Adherence20171141542128280313

- IvanovaJIBergmanREBirnbaumHGPhillipsALStewartMMeleticheDMImpact of medication adherence to disease-modifying drugs on severe relapse, and direct and indirect costs among employees with multiple sclerosis in the USJ Med Econ201215360160922376190

- LageMJCarrollCAFairmanKAUsing observational analysis of multiple sclerosis relapse to design outcomes-based contracts for disease-modifying drugs: a feasibility assessmentJ Med Econ20131691146115323844620

- Oleen-BurkeyMADorACastelli-HaleyJLageMJThe relationship between alternative medication possession ratio thresholds and outcomes: evidence from the use of glatiramer acetateJ Med Econ201114673974721913796

- SteinbergSCFarisRJChangCFChanATankersleyMAImpact of adherence to interferons in the treatment of multiple sclerosis: a non-experimental, retrospective, cohort studyClin Drug Investig201030289100

- TanHCaiQAgarwalSStephensonJJKamatSImpact of adherence to disease-modifying therapies on clinical and economic outcomes among patients with multiple sclerosisAdv Ther2011281516121153000

- ThomasNPCurkendallSFarrAMYuEHurleyDThe impact of persistence with therapy on inpatient admissions and emergency room visits in the US among patients with multiple sclerosisJ Med Econ201619549750526706292

- YermakovSDavisMCalnanMImpact of increasing adherence to disease-modifying therapies on healthcare resource utilization and direct medical and indirect work loss costs for patients with multiple sclerosisJ Med Econ201518971172025903661

- SabatéEAdherence to Long-Term Therapies: Evidence for ActionGenevaWorld Health Organization2003

- CramerJARoyABurrellAMedication compliance and persistence: terminology and definitionsValue Health2008111444718237359

- VrijensBDe GeestSHughesDAA new taxonomy for describing and defining adherence to medicationsBr J Clin Pharmacol201273569170522486599

- HeesenCBruceJFeysPAdherence in multiple sclerosis (ADAMS): classification, relevance, and research needs – a meeting reportMult Scler201420131795179824756569

- AgashivalaNWuNAbouzaidSCompliance to fingolimod and other disease modifying treatments in multiple sclerosis patients, a retrospective cohort studyBMC Neurol20131313824093542

- BergvallNPetrillaAAKarkareSUPersistence with and adherence to fingolimod compared with other disease-modifying therapies for the treatment of multiple sclerosis: a retrospective US claims database analysisJ Med Econ2014171069670725019581

- HigueraLCarlinCSAndersonSAdherence to disease-modifying therapies for multiple sclerosisJ Manag Care Spec Pharm201622121394140127882830

- MunsellMFreanMMenzinJPhillipsALAn evaluation of adherence in patients with multiple sclerosis newly initiating treatment with a self-injectable or an oral disease-modifying drugPatient Prefer Adherence201711556228115831

- JohnsonKMZhouHLinFKoJJHerreraVReal-world adherence and persistence to oral disease-modifying therapies in multiple sclerosis patients over 1 yearJ Manag Care Spec Pharm201723884485228737986

- ZimmerABläuerCCoslovskyMKapposLDerfussTOptimizing treatment initiation: effects of a patient education program about fingolimod treatment on knowledge, self-efficacy and patient satisfactionMult Scler Relat Disord20154544445026346793

- LeslieSRGwadry-SridharFThiebaudPPatelBVCalculating medication compliance, adherence, and persistence in administrative pharmacy claims databasesPharm Program2008111319

- NauDPProportion of days covered (PDC) as a preferred method of measuring medication adherence Available from: http://www.pqaal-liance.org/images/uploads/files/PQA%20PDC%20vs%20%20MPR.pdfAccessed February 26, 2017

- European Medicines AgencyGilenya [summary of product characteristics] Available from: http://www.ema.europa.eu/docs/en_GB/document_library/EPAR_-_Product_Information/human/002202/WC500104528.pdfAccessed September 5, 2017

- GrayRWykesTEdmondsMLeeseMGournayKEffect of a medication management training package for nurses on clinical outcomes for patients with schizophrenia: cluster randomised controlled trialBr J Psychiatry200418515716215286068

- FoundationRThe R Project for statistical computing Available from: http://www.r-project.orgAccessed September 5, 2017

- BayasAOualletJCKallmannBHuppertsRFuldaUMarhardtKAdherence to, and effectiveness of, subcutaneous interferon beta-1a administered by Rebismart in patients with relapsing multiple sclerosis: results of the 1-year, observational SMART studyExpert Opin Drug Deliv20151281239125026098143

- Dhib-JalbutSMarkowitzCPatelPBoatengFRamettaMThe combined effect of nursing support and adverse event mitigation on adherence to interferon beta-1b therapy in early multiple sclerosis: the START studyInt J MS Care201214419820824453752

- FernandezOArroyoRMartinez-YelamosSLong-term adherence to IFN β-1a treatment when using RebiSmart device in patients with relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosisPLoS One2016118e016031327526201

- JongenPJLemmensWAHuppertsRPersistence and adherence in multiple sclerosis patients starting glatiramer acetate treatment: assessment of relationship with care received from multiple disciplinesPatient Prefer Adherence20161090991727307711

- PaolicelliDCoccoEDi LecceVExploratory analysis of predictors of patient adherence to subcutaneous interferon beta-1a in multiple sclerosis: TRACER studyExpert Opin Drug Deliv201613679980526922837

- WillisHWebsterJLarkinAMParkesLAn observational, retrospective, UK and Ireland audit of patient adherence to subcutaneous interferon beta-1a injections using the RebiSmart injection devicePatient Prefer Adherence2014884385124966669

- de SezeJBorgelFBrudonFPatient perceptions of multiple sclerosis and its treatmentPatient Prefer Adherence2012626327322536062

- BruceJMHancockLMLynchSGObjective adherence monitoring in multiple sclerosis: initial validation and association with self-reportMult Scler201016111212019995835

- FernandezOAgueraEIzquierdoGAdherence to interferon β-1b treatment in patients with multiple sclerosis in SpainPLoS One201275e3560022615737

- MocciaMPalladinoRRussoCHow many injections did you miss last month? A simple question to predict interferon β-1a adherence in multiple sclerosisExpert Opin Drug Deliv201512121829183526371561

- TremlettHVan der MeiIPittasFAdherence to the immunomodulatory drugs for multiple sclerosis: contrasting factors affect stopping drug and missing dosesPharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf200817656557618395883

- DevonshireVLapierreYMacdonellRThe Global Adherence Project (GAP): a multicenter observational study on adherence to disease-modifying therapies in patients with relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosisEur J Neurol2011181697720561039

- DuchovskieneNMickevicieneDJurkevicieneGDirziuvieneBBalnyteRFactors associated with adherence to disease modifying therapy in multiple sclerosis: an observational survey from a referral center in LithuaniaMult Scler Relat Disord20171310711128427690

- PhillipsALKozmaCMLocklearJCUsing a panel survey to identify predictors of disease-modifying drug adherence in patients with multiple sclerosisValue Health2014177A400

- El AliliMVrijensBDemonceauJEversSMHiligsmannMA scoping review of studies comparing the medication event monitoring system (MEMS) with alternative methods for measuring medication adherenceBr J Clin Pharmacol201682126827927005306

- LehmannAAslaniPAhmedRAssessing medication adherence: options to considerInt J Clin Pharm2014361556924166659

- Schäfer-KellerPSteigerJBockADenhaerynckKDe GeestSDiagnostic accuracy of measurement methods to assess non-adherence to immunosuppressive drugs in kidney transplant recipientsAm J Transplant20088361662618294158

- BreckenridgeAAronsonJKBlaschkeTFHartmanDPeckCCVrijensBPoor medication adherence in clinical trials: consequences and solutionsNat Rev Drug Discov201716314915028154411

- UrquhartJRole of patient compliance in clinical pharmacokinetics: a review of recent researchClin Pharmacokinet19942732022157988102

- De GeestSAbrahamIMoonsPLate acute rejection and sub-clinical noncompliance with cyclosporine therapy in heart transplant recipientsJ Heart Lung Transplant19981798548639773856

- De GeestSBorgermansLGemoetsHIncidence, determinants, and consequences of subclinical noncompliance with immunosuppressive therapy in renal transplant recipientsTransplantation19955933403477871562

- NoensLvan LierdeMADe BockRPrevalence, determinants, and outcomes of nonadherence to imatinib therapy in patients with chronic myeloid leukemia: the ADAGIO studyBlood2009113225401541119349618

- AbrahamILeeCMacDonaldKNo margin for nonadherence: novel application of Kaplan-Meier methods to model the efficacy of adherence to imatinib treatment by patients with chronic myeloid leukemia (the ADAGIO study)Poster presented at: 15th Annual Meeting of the European Society for Patient Adherence, Compliance and Persistence (ESPACOMP)October 25–27, 2012Ghent, Belgium

- Gwadry-SridharFHManiasEZhangYA framework for planning and critiquing medication compliance and persistence research using prospective study designsClin Ther200931242143519302915

- PetersonAMNauDPCramerJABennerJGwadry-SridharFNicholMA checklist for medication compliance and persistence studies using retrospective databasesValue Health200710131217261111

- HancockLMBruceJMLynchSGExacerbation history is associated with medication and appointment adherence in MSJ Behav Med201134533033821259038

- JongenPJLemmensWAHoogervorstELDondersRGlatiramer acetate treatment persistence – but not adherence – in multiple sclerosis patients is predicted by health-related quality of life and self-efficacy: a prospective web-based patient-centred study (CAIR study)Health Qual Life Outcomes20171515028292329

- IacorossiLGambalungaFFabiAAdherence to oral administration of endocrine treatment in patients with breast cancer: a qualitative studyCancer Nurs Epub2016125

- Pages-PuigdemontNManguesMAMasipMPatients’ perspective of medication adherence in chronic conditions: a qualitative studyAdv Ther201633101740175427503082

- LapierreYO’ConnorPDevonshireVCanadian experience with fingolimod: adherence to treatment and monitoringCan J Neurol Sci201643227828326890887

- Warrender-SparkesMSpelmanTIzquierdoGThe effect of oral immunomodulatory therapy on treatment uptake and persistence in multiple sclerosisMult Scler201622452053226199347

- BrauneSLangMBergmannAEfficacy of fingolimod is superior to injectable disease modifying therapies in second-line therapy of relapsing remitting multiple sclerosisJ Neurol2016263232733326645389

- BruceJBruceALynchSA pilot study to improve adherence among MS patients who discontinue treatment against medical adviceJ Behav Med201639227628726563147

- Fernandez-FournierMTallon-BarrancoAChamorroBMartinez-SanchezPPuertasIDifferential glatiramer acetate treatment persistence in treatment-naive patients compared to patients previously treated with interferonBMC Neurol20151514126286576

- EspostiLDPiccinniCSangiorgiDChanges in first-line injectable disease-modifying therapy for multiple sclerosis: predictors of non-adherence, switching, discontinuation, and interruption of drugsNeurol Sci201738458959428078563