Abstract

Objective

The primary purpose of the present study was to survey the quality of life (QoL) in primary Sjögren’s syndrome (pSS) and to analyze the relationships between disease activity, anxiety/depression, fatigue, pain, age, oral disorders, impaired swallowing, sicca symptoms, and QoL.

Patients and methods

A survey was conducted on 185 pSS patients and 168 healthy individuals using the Short Form 36 health survey for QoL. Disease activity was assessed using the European League Against Rheumatism Sjögren’s Syndrome Disease Activity Index. We examined these data using independent samples t-tests, Mann–Whitney U test, chi squared analysis, and linear regression.

Results

The result for each domain in Short Form 36 health survey was lower in pSS patients than in healthy controls, especially the score in the dimension of role physical function. In the bivariate analysis, age, pain, fatigue, disease activity, disease complication, anxiety/depression, oral disorders, and impaired swallowing correlated with QoL. Also, in the linear regression model, pain, fatigue, disease activity, impaired swallowing, and anxiety/depression remained the main predictors of QoL.

Conclusion

pSS patients had a considerably impaired QoL compared to the controls, and pSS could negatively affect the QoL of patients. Measuring QoL should be considered as a vital part of the comprehensive evaluation of the health status of pSS patients, which could contribute some valuable clues in improving the management of disease and treatment decisions.

Background

Primary Sjögren’s syndrome (pSS) is a systemic autoimmune disease characterized by chronic inflammation of exocrine glands such as the lachrymal and salivary glands, leading to dry eyes and dry mouth.Citation1 A majority of pSS patients also suffer from extraglandular symptoms including fatigue, mental disorders, musculoskeletal, and neurological symptoms.Citation2 In addition, pSS patients exhibit a 44 times higher relative risk for lymphoma development compared to the general population.Citation3 This disease predominantly affects middle-aged women (women:men ratio 9:1), but can also be detected in children and the aged.Citation4 pSS is a common autoimmune rheumatic condition, second only in frequency to rheumatoid arthritis, with a prevalence between 0.1% and 4.8% in various populations.Citation5 pSS has a negative influence on health-related quality of life (HR-QoL)Citation6 and is associated with high health care costs,Citation7 pain,Citation8 fatigue,Citation9 work disability,Citation10 and anxiety/depression.Citation11 Moreover, dry mouth in pSS may lead to oral uncomfortableness, trouble talking, impaired swallowing, tooth decay, and continual oral infections. Though these complications are not life-threatening, the complication and chronicity of symptoms can lead to heavy debility and a reduction in patient’s quality of life (QoL).Citation12 Individuals with pSS also experience voice disturbances and specific voice-related manifestations that are related to decreased QoL.Citation13

QoL is defined as the general well-being of individuals and societies, based on the individual’s culture and life values with respect to that individual’s objectives, expectation, and standards. HR-QoL is the impact of disease and its treatment of the individual’s ability to function based on physical, mental, and social well-being.Citation14 Variables that may affect the QoL of pSS patients include disease activity, fibromyalgia,Citation15 comorbidity,Citation2 medical therapy,Citation16 pain, fatigue, dryness, and anxiety/depression. In the literature, there are various studies investigating fatigue and discomfort, oral HR-QoL,Citation17 employment and disability,Citation18 and psychological status of pSS patients. However, to our best knowledge, there are a few previous studies focusing on how these variables might affect the HR-QoL in pSS, especially in China. The objective of the present study was to evaluate QoL in pSS and to explore the relationships between disease activity, fatigue, anxiety/depression, oral disorders, impaired swallowing, pain, age, dryness, and QoL.

Patients and methods

Participants

The study was carried out in the Affiliated Hospital of Nantong University from July 2016 to July 2017. pSS patients were outpatients or inpatients from the Department of Rheumatology; age- and sex-matched controls were randomly selected from the general population. The Ethics Committee of the Affiliated Hospital of Nantong University approved this study (approval number 2017-K003), and all participants met the American–European Consensus Group Criteria for pSS and gave written informed consent. All study participants were asked to complete the related questionnaires. Medical assessments also were recorded. There was no significant difference between the two groups in terms of age, sex, education level, occupation, and income/year.

Inclusion criteria and exclusion criteria

Inclusion criteria consisted of pSS diagnosis, age over 18 years, no known cognitive deficits, and Chinese speaking. Exclusion criteria consisted of secondary Sjögren syndrome, having serious systemic diseases lately (lymphoma, similar renal/pulmonary involvement, myositis, or vasculitis), and participants with a physical or psychological problem (eg, cancer, psychiatric disorders) which may confound the outcome.

Methods

This study included 185 pSS patients according to the American–European Consensus Group criteria and 168 healthy controls. Sicca symptoms were assessed by the dryness domain of the European League Against Rheumatism Sjögren’s Syndrome Patient-Reported Index.Citation19 Disease activity was assessed using the European League Against Rheumatism Sjögren’s Syndrome Disease Activity Index (ESSDAI).Citation20 Mental state was assessed through Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale; it had acceptable internal consistency and test–retest reliability, with a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.85 and intraclass correlation coefficient of 0.90.Citation21 Independent samples t-tests, chi-squared analyses, Mann–Whitney U test, and linear regression modeling were used to analyze the data.

Demographics and clinical characteristics

Demographic characteristics and clinical variables were examined. Demographic variables included age, sex, education, marital status, and socioeconomic status. Next, differences in mean Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale scores and QoL scores between pSS patients and control groups were analyzed. Clinical data such as disease duration and medication use were obtained by asking the patients or searching their electronic medical records.

The medical outcomes study, 36-item short-form health survey (SF-36)

The SF-36 instrument is aimed to rate HR-QoL within the previous 4 weeks. It includes 36 statements, with eight scales assessing two dimensions. The first dimension is physical health function and includes the following four specific scores: physical functioning (the extent to which health interferes with various activities), physical role functioning (the extent to which health interferes with usual daily activities), bodily pain, and general health. These physical scores are summarized by the physical composite score (PCS). The second dimension is the mental health function, which includes the following four specific scores: vitality, social functioning, emotional role functioning (limitations due to emotional problems), and mental health. These four mental scores are summarized by the mental composite score (MCS). Each scale gives a standardized score that ranges from 0 to 100, with 0 illustrating the worst possible health state and 100 illustrating the best possible health state.Citation22,Citation23 In addition, this scale has been translated and validated for use in Hong Kong.Citation24,Citation25

Convergent validity and discriminant validity were satisfactory for all except the social functioning scale. Cronbach’s α coefficients ranged from 0.72 to 0.88 except 0.39 for the social functioning scale and 0.66 for the vitality scale. Two weeks test-retest reliability coefficients ranged from 0.66 to 0.94.Citation26

Fatigue severity scale

Fatigue was measured by using the fatigue severity scale. It is a self-reported instrument developed to explore the impact and severity of fatigue. It involves nine questions to assess the severity of fatigue, as it relates to daily activities such as physical functioning, exercise, work, and family/social life. The scores range from 1 to 7 for each item, with a lower score signifying less fatigue (the best condition is 9 points and the worst condition is 63 points). We used a cut-off score ≥4 to define fatigue.Citation27

Other related scales

Pain was investigated by the visual analog scale to identify pain severity. Patients were asked to estimate their experiences of pain during the last week, each on a visual analog scale of 0–10, with a higher score implying more severe pain.Citation28 The MD Anderson Dysphagia InventoryCitation29 measures patient’s swallowing disorders symptoms (score ranges from 0 to 100, with higher scores indicating more severe symptoms), and the Oral Health Impact Profile 14Citation30 was used to measure oral distress.

Data analysis

Data were analyzed by IBM SPSS 22.0 package program. Continuous variables were expressed as mean±SD. Before the continuous variables were compared, it was checked whether the parametric test assumptions were met or not. Qualitative variables were presented as numbers and percentages. The distinction between independent groups in terms of the qualitative variables was evaluated by using chi-squared test. While conformity to normal distribution was evaluated by using Shapiro–Wilk test, the homogeneity of the variances was examined by using the Levene’s test. The difference between independent groups in terms of numerical variables was investigated by using the independent samples t-test in cases where the parametric test assumptions were met and by using the Mann–Whitney U test in cases where the said assumptions were not met. The presence of a correlation between the numerical variables was determined by Spearman’s correlation coefficient. Multicollinearity between variables was checked by computing variance inflation factors before inclusion into the model. A backward procedure was used, removing variables with a P-value of >0.05 in the multivariable model in order of significance, until the best-fitting model was identified. While we regarded P-values <0.05 in each study as significant, we set stringent significant levels of P-values in the combined analysis based on Bonferroni’s correction.

Written informed consent

Written informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Results

Patient characteristics

Of the 203 eligible cases, 185 patients fully completed the provided questionnaires, with a rough response rate of 91%. In pSS patients (n=185), the mean age was 50.12±12.13 years, and 94.6% of the subjects were women. Demographic, clinical, and laboratory characteristics of the pSS patients and controls are presented in . Furthermore, the impact of disease-related variables on severity of depression and anxiety was assessed. Whether depression, anxiety, and disease-related variables can be determinants of QoL among affected individuals was also investigated. There was no significant difference in age, sex, education, occupation, and income/year between the pSS individuals and the controls (P>0.05). Tests of collinearity indicated good content validity.

Table 1 Demographic, clinical, and psychological characteristics of the pSS patients and controls

QoL of pSS patients and controls

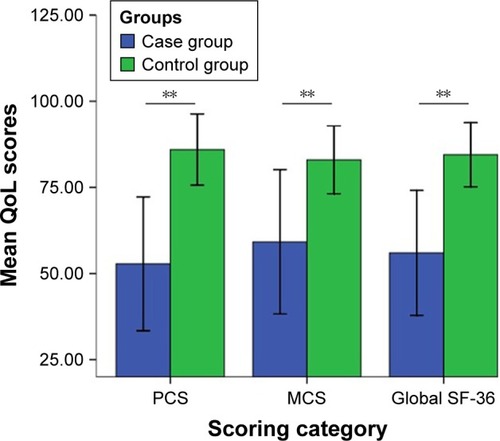

The scores of global SF-36, including PCS and MCS of pSS patients and the controls, are presented in . Eight domains of SF-36 of the pSS patients and controls are shown in . The average global SF-36 score of pSS patients was 56.01±18.13, ranging from 13.94 to 98.13. Compared with the controls, all SF-36 domains and total scores were much lower in pSS patients (P<0.01).

Figure 1 Global SF-36, PCS, and MCS among pSS patients and controls.

Abbreviations: MCS, mental composite score; PCS, physical composite score; pSS, primary Sjögren’s syndrome; QoL, quality of life; SF-36, Short Form 36 health survey.

Table 2 Eight domains in SF-36 of patients with pSS and the controls

Correlations between fatigue, disease activity etc, and QoL in pSS patients

As shown in , we found signifcant correlations between erythrocyte sedimentation rate, comorbidity, hospitalization, and European League Against Rheumatism Sjögren’s Syndrome Patient-Reported Index and QoL.

Table 3 Correlations between disease activity, anxiety/depression, fatigue, pain, age, and QoL in pSS patients

Stepwise linear regression analysis for the QoL

Stepwise linear regression analysis revealed depression, pain, and impaired swallowing were notably associated with the SF-36 PCS in pSS patients. Moreover, depression, anxiety, disease activity, fatigue, and impaired swallowing significantly accounted for the SF-36 MCS (). Finally, these variables explained 65.5% and 72.5% of the variance in PCS and MCS, respectively.

Table 4 Result of analysis of forward stepwise ordered linear regression models in SF-36

Discussion

pSS patients experience lower QoL compared to age-and sex-matched controls. Impaired QoL is associated with symptoms such as fatigue, pain, anxiety/depression, oral disorders, impaired swallowing, as well as disease activity, exemplifying the value of optimal management of all aspects of the disease. The underlying pathogenic process between depression and pSS remains unknown. Some studies attempted to explore depression in pSS patients; depression was reported as a relative factor of reduced QoL in Moroccan pSS patients.Citation31 Segal et alCitation32 stated that somatic fatigue was the main predictor of physical function and general health; additionally, depression was the key predictor of emotional well-being in the US. In agreement with the findings of previous studies, our study found that the strong correlation between MCS of the SF-36 and anxiety/depression in pSS patients emphasized the significance of the psychological dimension of SF-36. Consequently, recognition of determinants of depression and anxiety and their impact on QoL has noticeable clinical value, especially in China.

Fatigue is another essential symptom and has been reported to be associated with a reduction in HR-QoL in pSS.Citation33 A study from Germany reported that patients with pSS frequently suffer from fatigue that increases the risk of work disability and requires treatment by numerous health care specialists.Citation34 As expected, bivariate analysis showed that fatigue correlated with all domains of the SF-36. Fatigue and pain are the most common extraglandular symptoms,Citation35 and pain severity explained 14% of the variance in disability of daily activities in Korean patients with pSS.Citation36 Our results were in line with previous studies reporting that pain is a major symptomatic problem related to low physical functioning and health outcomes. Therefore, systematic monitoring of pain treatment seems essential.

The results showed that pSS patients had a moderate level of disease activity, with a mean ESSDAI score of 9.56. Similarly, the mean ESSDAI score of pSS patients from multicenter clinics of France was 9.04.Citation37 The comparison to age- and sex-matched healthy controls suggests that the disease-related symptoms of pSS patients are not attributed to the natural process of aging, but age was truly thought to play a crucial role in dysregulation of the neuroendocrine system.Citation38 We found that patient-perceived swallowing disorders were relatively common in pSS and increased with disease severity, which was uniquely associated with reduced QoL. Since eating and drinking form an important part of social interaction, dysphagic pSS patients often eat in seclusion because of shame. Also, they worry choking on their food or develop aspiration pneumonia. Frequent worries can decrease the QoL even more and aggravate anxiety. Therefore, health care professionals need to pay more attention to pSS patients who manifest swallowing symptoms and to strengthen the assessment of swallowing function of the pSS patients in clinical practice.

Notably, a significant difference was found in the marital status between the groups. The possible explanation is that women with pSS often suffer from vaginal dryness. Many pSS patients were unable to continue regular marital relationship due to sexual difficulties. Disease severity and disease duration may cause an increase in the divorce rate.

There are several limitations of this study. First, this study is cross-sectional in design, which does not allow for following up the progress of the examined variables during the course of the disease, and thus, we are unable to comment on the causal relationships. Second, it fails to make a distinction between men and women because of the great sex disparity. Third, all subjects were from a single hospital and the scales were all self-administered, which might give rise to possible biases of the outcomes. Even so, we still consider that our results may provide important insights into this complex process by identifying the associations between variables and QoL in pSS patients.

Conclusion

Patients with pSS had a considerable impaired QoL in comparison with the healthy subjects. pSS could have an unfavorable influence on the QoL of patients. Measuring QoL should be considered as a vital part of the comprehensive evaluation of the health status of pSS patients, which could contribute some valuable clues to improving the management of disease and treatment decisions.

Acknowledgments

This study was funded by the Chinese National Natural Science Foundation (Grant no 81671616 and 81471603), Jiangsu Provincial Commission of Health and Family Planning Foundation (Grant no H201317 and H201623), the Science Foundation of Nantong City (Grant no MS32015021, MS2201564, MS22016028, and MS22016019), and the Science and Technology Foundation of Nantong City (Grant no HS2014071 and HS2016003).

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- XiaoFNeuromyotonia as an unusual neurological complication of primary Sjögren’s syndrome: case report and literature reviewClin Rheumatol201736248148427957617

- LacknerAFicjanAStradnerMHIt’s more than dryness and fatigue: The patient perspective on health-related quality of life in primary Sjögren’s syndrome – a qualitative studyPLoS One2017122e1720562017-02-09

- PapageorgiouAVoulgarelisMTzioufasAGClinical picture, outcome and predictive factors of lymphoma in Sjögren syndromeAutoimmun Rev201514764164925808075

- Brito-ZeroNPBSjogren syndromeNat Rev Dis Primers201621604727383445

- GuptaSGuptaNSjögren Syndrome and Pregnancy: A Literature ReviewPerm J20172116047

- CornecDDevauchelle-PensecVMarietteXSevere health-related quality of life impairment in active primary Sjögren’s syndrome and patient-reported outcomes: data from a large therapeutic trialArthritis Care Res2017694528535

- MilinMCornecDChastaingMSicca symptoms are associated with similar fatigue, anxiety, depression, and quality-of-life impairments in patients with and without primary Sjögren’s syndromeJoint Bone Spine201683668168526774177

- KohJHKwokSKLeeJPain, xerostomia, and younger age are major determinants of fatigue in Korean patients with primary Sjögren’s syndrome: a cohort studyScand J Rheumatol2017461495527098775

- KarageorgasTFragioudakiSNezosAKaraiskosDMoutsopoulosHMMavraganiCPFatigue in primary Sjögren’s syndrome: clinical, laboratory, psychometric, and biologic associationsArthritis Care Res2016681123131

- MandlTJørgensenTSSkougaardMOlssonPKristensenLEWork disability in newly diagnosed patients with primary Sjögren syndromeJ Rheumatol201744220921528148755

- KoçerBTezcanMEBaturHZCognition, depression, fatigue, and quality of life in primary Sjögren’s syndrome: correlationsBrain Behav2016612e586

- LeungKCMcmillanASWongMCLeungWKMokMYLauCSThe efficacy of cevimeline hydrochloride in the treatment of xerostomia in Sjögren’s syndrome in southern Chinese patients: a randomised double-blind, placebo-controlled crossover studyClin Rheumatol200827442943617899308

- TannerKPierceJLMerrillRMMillerKLKendallKARoyNThe quality of life burden associated with voice disorders in Sjögren’s syndromeAnn Otol Rhinol Laryngol2015124972172725841042

- AbushakraMQuality of Life, Coping and Depression in Systemic Lupus ErythematosusIsr Med Assoc J2016183–414414527228629

- El-RabbatMSMahmoudNKGheitaTAClinical significance of fibromyalgia syndrome in different rheumatic diseases: relation to disease activity and quality of lifeRheumatol Clin2017

- JiangQZhangHPangRChenJLiuZZhouXAcupuncture for primary Sjögren syndrome (pSS) on symptomatic improvements: study protocol for a randomized controlled trialBMC Complement Altern Med20171716128103850

- CatanzaroJDinkelSSjögren’s syndrome: the hidden diseaseMedsurg Nurs201423421922325318334

- MeijerJMMeinersPMHuddleston SlaterJJHealth-related quality of life, employment and disability in patients with Sjogren’s syndromeRheumatology20094891077108219553376

- SerorRBowmanSJBrito-ZeronPEULAR Sjögren’s syndrome disease activity index (ESSDAI): a user guideRMD Open201511e22

- SerorRRavaudPMarietteXEULAR Sjogren’s Syndrome Patient Reported Index (ESSPRI): development of a consensus patient index for primary Sjogren’s syndromeAnn Rheum Dis201170696897221345815

- WangWChairSYThompsonDRTwinnSFA psychometric evaluation of the Chinese version of the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale in patients with coronary heart diseaseJ Clin Nurs200918172436244319694877

- DassoukiTBenattiFBPintoAJObjectively measured physical activity and its influence on physical capacity and clinical parameters in patients with primary Sjögren’s syndromeLupus201726769069727798360

- WareJEGandekBKosinskiMThe equivalence of SF-36 summary health scores estimated using standard and country-specific algorithms in 10 countries: results from the IQOLA project. International Quality of Life AssessmentJ Clin Epidemiol19985111116711709817134

- LamCLGandekBRenXSChanMSTests of scaling assumptions and construct validity of the Chinese (HK) version of the SF-36 health surveyJ Clin Epidemiol19985111113911479817131

- LamCLTseEYGandekBFongDYThe SF-36 summary scales were valid, reliable, and equivalent in a Chinese populationJ Clin Epidemiol200558881582216018917

- LiLWangHMShenYChinese SF-36 health survey: translation, cultural adaptation, validation, and normalisationJ Epidemiol Community Health200357425926312646540

- KruppLBLaroccaNGMuir-NashJSteinbergADThe fatigue severity scale. Application to patients with multiple sclerosis and systemic lupus erythematosusArch Neurol19894610112111232803071

- SokkaTKankainenAHannonenPScores for functional disability in patients with rheumatoid arthritis are correlated at higher levels with pain scores than with radiographic scoresArthritis Rheum200043238638910693879

- PierceJLTannerKMerrillRMMillerKLKendallKARoyNSwallowing disorders in Sjögren’s syndrome: prevalence, risk factors, and effects on quality of lifeDysphagia2016311495926482060

- EngerTBPalmØGarenTSandvikLJensenJLOral distress in primary Sjögren’s syndrome: implications for health-related quality of lifeEur J Oral Sci2011119647448022112034

- Ibn YacoubYRostomSLaatirisAHajjaj-HassouniNPrimary Sjögren’s syndrome in Moroccan patients: characteristics, fatigue and quality of lifeRheumatol Int20123292637264321786120

- SegalBBowmanSJFoxPCPrimary Sjögren’s syndrome: health experiences and predictors of health quality among patients in the United StatesHealth Qual Life Outcomes2009746119134191

- ChoHJYooJJYunCYThe EULAR Sjogren’s syndrome patient reported index as an independent determinant of health-related quality of life in primary Sjogren’s syndrome patients: in comparison with non-Sjogren’s sicca patientsRheumatology201352122208221724023247

- WesthoffGDörnerTZinkAFatigue and depression predict physician visits and work disability in women with primary Sjögren’s syndrome: results from a cohort studyRheumatology201251226226921705778

- SegalBThomasWRogersTPrevalence, severity, and predictors of fatigue in subjects with primary Sjögren’s syndromeArthritis Rheum200859121780178719035421

- ShimE-JHahmB-JGoDJModeling quality of life in patients with rheumatic diseases: the role of pain catastrophizing, fear-avoidance beliefs, physical disability, and depressionDisabil Rehabil201840131509151628291952

- SerorRRavaudPBowmanSJEULAR Sjogren’s syndrome disease activity index: development of a consensus systemic disease activity index for primary Sjogren’s syndromeAnn Rheum Dis20106961103110919561361

- OxenkrugGFMetabolic syndrome, age-associated neuroendocrine disorders, and dysregulation of tryptophan-kynurenine metabolismAnn N Y Acad Sci20101199111420633104