Abstract

Background

Patients’ non-adherence to diabetes medication is associated with poor glycemic control and suboptimal benefits from their prescribed medication, which can lead to worsening of medical condition, development of comorbidities, reduced quality of life, elevated health care costs, and increased mortality.

Objective

This study aimed to assess medication adherence among patients with diabetes and associated factors in Bisha primary health care centers (PHCCs) in Saudi Arabia.

Patients and methods

A cross-sectional study was conducted with a sample of 375 type 1 and 2 Saudi diabetic patients attending PHCCs under the Health Affairs of the Bisha governorate. The participants were aged 18 years and above, and had been taking diabetes medications for at least 3 months. Pregnant women, patients with mental illnesses, and those who were not willing to participate were excluded. Adherence to diabetes medications was measured using the four-item Morisky Green Levine Medication Adherence Scale (MGLS). All participants completed a self-report questionnaire including sociodemographic and clinical variables. Univariate and multivariate analyses were carried out using SPSS version 22.

Results

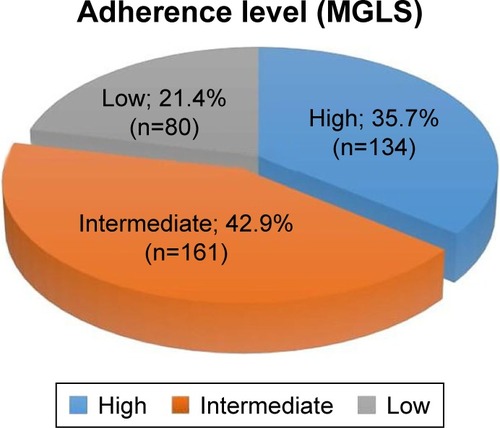

Of all the respondents, 134 (35.7%), 161 (42.9%), and 80 (21.4%), patients had high (MGLS score 0), intermediate (MGLS score 1 or 2), and low adherence (MGLS score ≥3), respectively. Factors associated with the level of adherence in univariate analysis were occupational status (P=0.037), current medication (P<0.001), glycated hemoglobin (A1c) (P<0.001), and number of associated comorbidities (P<0.001). In multivariable analyses, A1c <7 (P<0.001) and no associated comorbidities (P<0.003) variables remained significantly associated with adherence.

Conclusion

The level of adherence to medication in diabetes mellitus patients in the Bisha PHCCs was found to be suboptimal. The findings point toward the need for better management of primary health care providers’ approaches to individual patients, by taking into account their medication adherence levels. Better identification of patients’ level of adherence remains essential for successful diabetes treatment.

Introduction

Diabetes mellitus (DM), the most common disorder of the endocrine system, is a growing worldwide epidemic with the number of people with diabetes rising from 108 million in 1980 to 422 million in 2014.Citation1 Chronic hyperglycemia and other metabolic disturbances of DM lead to potential long-term complications including cardiovascular diseases, retinopathy, nephropathy, neuropathy, and diabetic foot disorders.Citation2,Citation3 Diabetes can be managed well by adherence to prescribed oral hypoglycemic agents (OHAs) and/or insulin. The glycated hemoglobin (A1c) test measures the average blood glucose of patients for the previous 2–3 months and has strong predictive value for diabetes complications. To reduce the risk of long-term complications of diabetes, a reasonable A1c goal for non-pregnant adults is <7%.Citation4

The Middle East has seen some of the highest growth in the amount of DM sufferers worldwide; five out of the top ten nations with the highest diabetes occurrence are in the Middle East, and trends estimate that the region will show a disease growth of more than 90% by 2030.Citation5,Citation6 In Saudi Arabia, there has been an 8% rise in the prevalence of DM over the past 10 years and currently, approximately 25% of Saudi residents are diabetic.Citation7

The WHO defines adherence for long-term treatment as “the extent to which a person’s behaviour – taking medication, following a diet, and/or executing lifestyle changes, corresponds with agreed recommendations from a health care provider”.Citation8,Citation9 According to the WHO report, the average adherence to long-term therapy for chronic diseases in developed countries is approximately 50%, and in developing countries the adherence rate is even lower. The report illustrated that the range of adherence for medicines is 31%–71% and much lower for lifestyle instructions, even with the availability of up-to-date and effective methods of treatment.Citation9 As a result, poor medication adherence leads to worsening of the disease and increased mortality, and imposes a significant financial burden on both the individual patient and the health care system. Globally, diabetes accounts for 11% of total health care expenditure in 2011. In 2017, the total estimated cost of diabetes in the US was ≥327 billion.Citation10 In Saudi Arabia, the national health care burden from DM reached ≥0.9 billion in 2010, and this number is projected to exceed ≥6.5 billion by 2020.Citation11 Actually, between 33% and 69% of all medication-related hospital admissions in the US are due to poor medication adherence, at a cost ranging from ≥100–≥300 annually.Citation8,Citation12,Citation13 Balkrishan et al observed that each 10% increase in adherence among diabetes patients was associated with an 8.6%–28.9% decrease in total annual health care costs.Citation14 Recently, Egede et al found, in a longitudinal 4-year study of more than 700,000 veterans with type 2 DM, that non-adherent patients can have annual inpatient costs 41% higher compared to adherent patients, and assumed that significant costs could be avoided by improving adherence.Citation15

At present, there is no gold standard method of measuring medication adherence.Citation16 Adherence rates for patients with diabetes range from 65%–85% for OHAs and 60%–80% for insulin.Citation17 Studies have suggested that the acceptable cutoff point for adherence rate is 80% or higher.Citation16,Citation18,Citation19 Among the many methods of evaluating medication adherence, patients’ self-reporting measures remain the most common approach.Citation16,Citation20,Citation21 The four-item Morisky Green Levine Medication Adherence Scale (MGLS) ranks the degree of adherence. The MGLS is also known as Medication Adherence Questionnaire and Morisky Scale. This scale has a number of advantages over other patient self-reporting instruments such as being a short scale, the quickest to administer, the easiest to score, it identifies barriers to non-adherence, it has widespread use in different diseases, and it is the most adaptable across populations, resulting in less response burden.Citation16,Citation22 As the MGLS has been validated in the broadest range of diseases including for patients with low literacy, it is the most widely used scale for research.Citation20–Citation22

Bisha is a governorate in the south-western Saudi Arabian region called Aseer. Bisha Health Affairs provides health care services in both rural and urban areas. By 2017, the population had increased to exceed 300,000 people with approximately 14,000 diabetes patients registered in primary health care centers (PHCCs).Citation23,Citation24 There has been no previous study on the prevalence of adherence of DM patients in the governorate. Therefore, this study was undertaken with the goal of assessing the medication adherence and determining factors linked to non-adherence among diabetes patients in PHCCs of the Health Affairs of Bisha governorate.

Patients and methods

Study design and setting

This study was performed within a 4-month period, starting from August 2017, among diabetes patients in six sectors of Bisha Health Affairs PHCCs. The study adopted a cross-sectional research design using a self-report survey method for data collection.

Participants

Sampling was conducted for the selection of patients with diabetes. Saudi female and male patients aged ≥18 years who had either type 1 or type 2 DM were included. To be included in the study, participants with diagnosed diabetes needed to be on drug treatment rather than diet control alone, for at least 3 months at the time of enrollment. However, pregnant women, patients with mental illnesses, and those unwilling to participate were excluded. Furthermore, terminally ill patients were not enrolled in this research.

Data collection

In this cross-sectional survey, the questionnaires were distributed to the participants through a self-administered method during their attendance at the PHCCs. For 136 illiterate participants, the survey was filled-out by their relatives. All participants completed a self-report questionnaire based on study variables including sociodemographic characteristics (nationality, gender, age, residence, marital status, education level, and occupational status) and clinical profile (disease type, disease duration, current medications, recent A1c result, and other comorbidities if present).

The MGLS was used to assess patient adherence to diabetic medications with permission from the scale owner. The composite four items in this adherence scale were: “Q1: Do you ever forget to take your diabetic medication?”; “Q2: Do you ever have problems remembering to take your diabetic medication?”; “Q3: When you feel better, do you sometimes stop taking your diabetic medication?”; and “Q4: Sometimes if you feel worse when you take your diabetic medication, do you stop taking it?”.Citation21 The validated Arabic version of the MGLS was obtained with permission for use in this study.Citation25 On the other hand, the availability of the most recent A1c (not older than 3 months) was documented by patients in the questionnaire or by referring to the last reading of the laboratory results from patients’ medical records. Sometimes at follow-up visits, patients brought A1c results performed in private laboratories or other hospitals which were documented before the collection of surveys by the researchers.

Assessment of adherence

Assessment of adherence to diabetic medications was based on patients’ self-reported recall of using diabetic medications over the previous 2 weeks using MGLS. The degree of adherence was determined according to the MGLS resulting from the counting of all “yes” answers. In this scale, scores gained from the MGLS ranged from 0–4 and each of the four items was in a (yes/no) format. One point was scored for each positive response, 1 point was given for a “yes” answer, and 0 points were given for a “no” answer. So, the lower the score, the more adherence, since the four questions were negatively coded items. A score of 0 indicated high adherence; a score of 1 or 2 illustrated intermediate adherence; and a score of 3 or 4 indicated low adherence.Citation20,Citation21,Citation25

On the other hand, according to the American Diabetes Association guidelines, the standard A1c goal for adults is less than 7.0%. However, this can differ according to individual circumstances. In this study, patients were categorized into two glycemic control groups: good control (A1c <7%) and poor control (A1c ≥7%).Citation4,Citation26

Statistical analysis

The data were entered into a computer for analysis using SPSS (IBM Corporation, Armonk, NY, USA) version 22 for Windows. Descriptive analysis was undertaken to present an overview of the findings from this study sample. Differences between groups were examined using a chi-squared test to assess the association of different sociodemographic data with adherence to diabetic medications and cross-tabulations to compare responses from different groups. A multivariable regression model was used in order to address the study objectives. A P-value less than 0.05 was taken to indicate a statistically significant association.Citation27

Ethical statement

In this study, the confidentiality of all participants was ensured. The ethical approval for conducting the study was obtained from the Institutional Review Board (IRB) of the Riyadh Elm University, formerly Riyadh Colleges of Dentistry and Pharmacy Research Centre (RCsDP), Riyadh, Saudi Arabia (approval number: RC/IRB/2016/602). The study was explained to all potential respondents, and all of the participants had provided written informed consent. The study was carried out in accordance with the tenets of the Declaration of Helsinki. Moreover, permission was also obtained from Bisha Health Affairs, Ministry of Health of Saudi Arabia, to visit PHCCs and conduct the study.

Results

A total of (n=375) subjects aged 18–40 years (21.1%), 41–59 years (43.2%), and ≥60 years (35.7%) were included in the analysis, and all participants were Saudi nationals. One hundred and ninety-six (52.3%) respondents participating in the study were male. The majority of the patients were rural residents (76.5%, n=287). Over one-third of the respondents were uneducated (36.3%, n=136). The majority of the patients were married (69.6%, n=261). A total of 27.7% (n=104) of the study population were employed. The majority (57.3%, n=215) of the patient sample was classified as having a lower middle income of 5,000–10,000 Saudi Arabian Riyal (SAR) per month. The sociodemographic variables of the participants are summarized in .

Table 1 Association between patients’ sociodemographic characteristics and adherence level to DM medication

The majority of the study population was diagnosed with type 2 diabetes (80%, n=300) and 80.5% (n=302) had both types of DM for ≥5 years. Approximately half of the patients were being treated with only OHAs (55.2%, n=207). In addition, in just over half of the respondents (51.7%, n=184) A1c was 7%–8%, and the majority had poor control of A1c ≥7% (68%, n=255). One hundred and sixty-four (43.7%) patients reported no associated comorbidities. The clinical variables of the participants are shown in .

Table 2 Association between clinical variables and medication adherence

The responses to the questions of the MGLS are presented in . The majority of participants reported that they often forgot to take their diabetic medicine (54.4%, n=204). Approximately two-thirds reported that they were not careless when taking their prescribed medications (65.9%, n=247). Approximately three-quarters of the patients reported that they did not stop taking their DM medicine when they felt better (75.5%, n=283) or felt worse (75.7%, n=284).

Table 3 Patients’ self-reported adherence to diabetic medications according to the MGLS

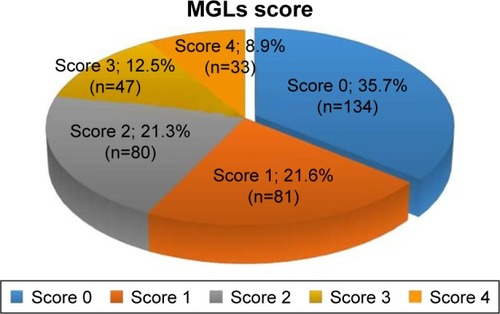

One hundred and thirty-four (35.7%) respondents had an MGLS score =0, followed by 21.6% (n=81) scoring 1, 21.3% (n=80) had a score of 2, 12.5% (n=47) scored 3, and 8.9% (n=33) scored 4. The distribution of MGLS scores is presented in . In addition, 161 (42.9%) respondents were considered to have intermediate adherence to DM medication, followed by 35.7% (n=134) with a high level of adherence and 21.4% (n=80) with a low level of adherence. The scored numbers and proportions of DM patients in each MGLS category are illustrated in .

Figure 1 The frequency and percentages of respondents according to MGLS score.

Figure 2 The frequency and percentage of patients in each MGLS category.

In , except for occupation status, there was no difference in sociodemographic characteristics by level of adherence. The chi-squared test showed statistical significance only with occupational status. It found that occupational status was significantly associated with a high level of adherence (χ2=13.39; P=0.037). Other sociodemographic factors like gender, age, residence, education, marital status, and family income were not significantly associated with high adherence. However, the multivariate analysis results in show no statistically significant difference between medication adherence among employed patients and others (student, retired, unemployed).

Table 4 Multivariable analysis of the association between adherence level and sociodemographic and clinical factors among patients with diabetes

As shown in , the chi-squared test and two-way cross-tabulation indicated statistical significance with the current medication section (χ2=21.941; P<0.001). In addition, the study displayed a statistically significant association between level of adherence to DM medication and A1c (χ2=80.475; P<0.001) and associated comorbidities (χ2=27.205; P<0.001).

presents the results of the multivariate logistic regression model showing variables significantly associated with medication adherence. As shown in the table, a high level of adherence to diabetic medications was significantly associated with A1c <7 (P<0.001) as well as no associated comorbidities (P=0.003) compared to the intermediate or low adherence to diabetic medications. Respondents with A1c <7 were more likely to have high adherence, and A1c ≥7 had a low level. Respondents with no associated comorbidities were considered to have a high level of adherence, those with ≥1 associated comorbidities had poor adherence, which was found to be statistically significant. However, the result found no statistically significant association between medication adherence and sociodemographic variables such as patients who are employed and others, and clinical variables like disease duration and pharmaceutical regimen.

Discussion

The reasonable threshold for adherence rate is 80% or higher.Citation16,Citation18,Citation19 In this study, MGLS was used to evaluate medication adherence among patients with diabetes. It reported 134 (35.7%), 161 (42.9%), and 80 (21.4%) PHCC patients with DM had high, intermediate, and low adherence, respectively. The current outcome (35.7%) of good medication adherence was higher than a previous national outcome reported from Jazan (23%)Citation28 and Al Hasa (32.1%).Citation29 Globally, the research findings were suboptimal and lower than that from earlier studies in Palestine (58%),Citation25 Malaysia (47%),Citation30 and France (39%).Citation17,Citation31

The reported adherence in this study among DM patients remains unsatisfactory and similar to prior findings reported from Switzerland (40%),Citation32 Tanzania (60%),Citation33 Ethiopia (51.3%),Citation34 Egypt (38.9%),Citation35 and Uganda (71.2).Citation19 Also, this suboptimal finding is in line with the outcome of a systematic review of 20 research articles published between 1966 and 2003 which focused on adherence to OHAs and insulin and correlations between adherence rates and glycemic control.Citation36 The review recorded non-adherence rates ranging from 37%–51% and showed that patients with diabetes were often non-adherent to their treatment, potentially leading to poor health outcomes. The published review data concluded that among patients with diabetes, hypertension, and dyslipidemia, only 59% had adherence rates of a medication posession ratio =80%. However, an Oman study reported an overall good patient adherence to the medication regimen (80%), higher than our finding.Citation17 But, the sample size was small, which makes it difficult to generalize the results to the overall target population.

On the basis of occupation, the study suggested that employment was predicted to be an important factor related to high adherence. The chi-squared test showed statistical significance with occupational status. However, using the multivariate analysis, occupational status was not statistically significant. These findings are similar to results from other reviews in Jazan, Saudi Arabia,Citation28 Oman,Citation17 and Uganda,Citation19 where no statistically significant relationship was found between occupation status and adherence to DM treatments. To avoid controversy, further prospective studies are recommended to find out the possible contribution of occupational status to patients’ adherence.

Current medication regimen showed significant association with adherence in the univariate analysis. Patients taking insulin was a predictor of high adherence in this study. However, the significance of the association between medication regimen and adherence seen in the univariate analysis diminished in the multivariate analysis. This finding is consistent with the Jazan study which found no association between the type of treatment and medication adherence.Citation28 Even if free medicines were available through government PHCCs, the insignificant association could be attributed to many factors. This finding could be an indication of ineffective communication between patients and health care professionals and inadequate knowledge of the disease medications or awareness of its complications.

Generally, the number of drugs taken by patients was dependent on DM severity and associated comorbidities. Therefore, a patient with regimen complexity could pose a challenge to continued adherence to all prescribed medications. A previous study demonstrated reduced adherence in participants with several comorbidities due to multiple medications.Citation8 So, patients with diabetes with comorbidities generally have more drugs of different pharmacological classes. This complex treatment regimen could be a factor that contributes toward non-adherence, as people tend to forget to take their medications when they are exhausted from work. In our study, patients with no associated comorbidities were found to have a statistically significant association with high adherence. This finding was similar to a Malaysian study that indicated that presence of comorbidities was associated with poor adherence to antidiabetic treatment.Citation30 On the other hand, studies from Tanzania and Switzerland showed good adherence among elderly patients likely to have multiple comorbidities when more information was provided on the benefits of adherence to medications.Citation32,Citation33

Adherence to diabetic medications was found to be positively associated with a decrease in A1c.Citation37,Citation38 Jazan, Saudi Arabian, and French studies showed that improved adherence to DM medication was associated with better glycemic control.Citation28,Citation31 These findings demonstrate that patients with poor adherence show poor glycemic control. In our study, poor glycemic control (A1c ≥7%) was reported among more than half of participants (68%). There was a statistically significant association between the MGLS categories (high, intermediate, low adherence) and A1c in the univariate analysis. Respondents with A1c <7 were more likely to have high adherence, and A1c ≥7 had a poor adherence level. These associations remained statistically significant after multivariate adjustment. The study demonstrated that good blood glucose control of A1c <7% was higher among patients with high adherence to their DM medication compared with other non-adherent counterparts. Also, patients who had poor adherence (intermediate and low level) were found to have significantly higher glycemic control values (A1c ≥7%).

There is no gold standard method to evaluate medication-taking behavior.Citation16,Citation30 Studies have stated that adopting a valid scale such as the MGLS to measure adherence level is correct because the sensitivity and specificity are over 70%.Citation25,Citation39 The current study has a number of limitations. First, the use of a self-report method to evaluate patient adherence can lead to overestimation of adherence.Citation16,Citation40 The adherence data were based on participants’ recall, and so the real and true prevalence of adherence could be less than the presented results in this research. Patients might have difficulties remembering their habits and medication-taking behaviors, but this impact was diminished by asking participants to remember within the prior 2-week period.Citation8,Citation25 Second, selection bias might have occurred since participants who attend PHCCs typically care more about their health. Third, the relationship between patients and their health care providers, affecting their level of adherence to DM medication, was not included in this study. As a result, a good physician–patient relationship could be associated with better medication adherence and high patient satisfaction. On the other hand, the main strengths of this study are that there have been no previously published studies evaluating medication adherence among Saudi DM patients in the Bisha governorate. Also, gender representativeness in the study sample was observed. Finally, glycemic control data (A1c) were obtained to assist in linking adherence to glycemic control.

Conclusion

This study showed that the level of adherence to DM medications among patients attending PHCCs of Bisha governorate was suboptimal. Even when free medicines were available with a high level of health care access through government PHCCs, our study demonstrated poor adherence. Variations were observed between high, intermediate, and low adherence level regarding occupational status, current medication, A1c level, and number of comorbidities. Using multivariate analysis, two factors associated with high adherence to diabetic medications were A1c and patients with no associated comorbidities, and these were statistically significant. The findings point toward the need for better management of primary health care providers’ approach to individual patients by taking into account their medication adherence levels. Better identification of patients’ level of adherence remains essential for successful diabetes treatment. Our recommendations for future work is to use a combination of other methods of evaluating diabetes medication adherence to confirm the results of the tool’s findings. Also, further research is recommended to include other factors that could influence adherence, such as patient–health care provider communication. Moreover, it is recommended that PHCCs use a validated medication adherence measure for all patients as part of their care plan, to identify patients who are non-adherent.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to express their deepest gratitude to Bisha Health Affairs, Ministry of Health, for permission to conduct this research. Our appreciation also extends to all members of the Public Health Administration and PHCCs of Bisha governorate for their support and cooperation.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- RoglicGWorld Health Organization. Global Report on DiabetesWHO2016 Available from: http://www.who.int/iris/handle/10665/204871Accessed October 10, 2018

- AscheCLaFleurJConnerCA review of diabetes treatment adherence and the association with clinical and economic outcomesClin Ther20113317410921397776

- MaddiganSLFeenyDHJohnsonJAHealth-related quality of life deficits associated with diabetes and comorbidities in a Canadian National Population Health SurveyQual Life Res20051451311132016047506

- American Diabetes AssociationStandards of Medical Care in Diabetes-2017: Summary of RevisionsDiabetes Care201740Suppl 1S4S527979887

- BenerAZirieMJanahiIMAl-HamaqAOMusallamMWarehamNJPrevalence of diagnosed and undiagnosed diabetes mellitus and its risk factors in a population-based study of QatarDiabetes Res Clin Pract20098419910619261345

- ShawJESicreeRAZimmetPZGlobal estimates of the prevalence of diabetes for 2010 and 2030Diabetes Res Clin Pract201087141419896746

- Al-KhaldiYMKhanMYKhairallahSHAudit of referral of diabetic patientsSaudi Med J200223217718111938394

- OsterbergLBlaschkeTAdherence to medicationN Engl J Med2005353548749716079372

- SabatéEWHO Adherence to Long Term Therapies Project, Global Adherence Interdisciplinary Network, World Health Organization Dept. of Management of Noncommunicable Diseases. Adherence to long-termtherapies: evidence for actionGenevaWorld Health Organization2003 Available from: http://whqlibdoc.who.int/publications/2003/9241545992.pdfAccessed October 6, 2018

- American Diabetes AssociationEconomic Costs of Diabetes in the U.S. in 2017Diabetes Care201841591792829567642

- AlhowaishAKEconomic costs of diabetes in Saudi ArabiaJ Family Community Med20132011723723724

- Durán-VarelaBRRivera-ChaviraBFranco-GallegosEPharmacological therapy compliance in diabetesSalud Publica Mex200143323323611452700

- BenjaminRMMedication adherence: helping patients take their medicines as directedPublic Health Rep201212712322298918

- BalkrishnanRRajagopalanRCamachoFTHustonSAMurrayFTAndersonRTPredictors of medication adherence and associated health care costs in an older population with type 2 diabetes mellitus: a longitudinal cohort studyClin Ther200325112958297114693318

- EgedeLEGebregziabherMDismukeCEMedication nonadherence in diabetes: longitudinal effects on costs and potential cost savings from improvementDiabetes Care201235122533253922912429

- LamWYFrescoPMedication Adherence Measures: An OverviewBiomed Res Int Epub20151011

- JimmyBJoseJAl-HinaiZAWadairIKAl-AmriGHAdherence to medications among type 2 diabetes mellitus patients in three districts of Al Dakhliyah governorate, Oman: A cross-sectional pilot studySultan Qaboos Univ Med J2014142e231e23524790747

- KirkmanMSRowan-MartinMTLevinRDeterminants of adherence to diabetes medications: findings from a large pharmacy claims databaseDiabetes Care201538460460925573883

- KalyangoJNOwinoENambuyaAPNon-adherence to diabetes treatment at Mulago Hospital in Uganda: prevalence and associated factorsAfr Health Sci200882677319357753

- KrapekKKingKWarrenSSMedication adherence and associated hemoglobin A1c in type 2 diabetesAnn Pharmacother20043891357136215238621

- MoriskyDEGreenLWLevineDMConcurrent and predictive validity of a self-reported measure of medication adherenceMed Care198624167743945130

- LavsaSMHolzworthAAnsaniNTSelection of a validated scale for measuring medication adherenceJ Am Pharm Assoc (2003)2011511909421247831

- MOIEmirate of Province Aseer Governorates of Aseer2018 Available from: https://www.moi.gov.sa/wps/portal/Home/emirates/aseer/contentsAccessed October 10, 2018

- Ministry of Health SAHealth statistical yearbook 1436HDRiyadhMOH2015

- ElsousARadwanMAl-SharifHAbu MustafaAMedications adherence and associated factors among patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus in the gaza strip, palestineFront Endocrinol (Lausanne)2017810028649231

- AshurSTShamsuddinKShahSABosseriSMoriskyDEReliability and known-group validity of the Arabic version of the 8-item morisky medication adherence scale among type 2 diabetes mellitus patientsEast Mediterr Health J2015211072272826750162

- MackinnonAA spreadsheet for the calculation of comprehensive statistics for the assessment of diagnostic tests and inter-rater agreementComput Biol Med200030312713410758228

- AlhazmiTSharahiliJKhurmiSDrug Compliance among Type 2 Diabetic patients in Jazan Region, Saudi ArabiaInt J Adv Res201751966974

- KhanARAl-Abdul LateefZNAl AithanMABu-KhamseenMAAl IbrahimIKhanSAFactors contributing to non-compliance among diabetics attending primary health centers in the Al Hasa district of Saudi ArabiaJ Family Community Med2012191263222518355

- AhmadNSRamliAIslahudinFParaidathathuTMedication adherence in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus treated at primary health clinics in MalaysiaPatient Prefer Adherence2013752553023814461

- TivMVielJFMaunyFMedication adherence in type 2 diabetes: the ENTRED study 2007, a French Population-Based StudyPLoS One201273e3241222403654

- HuberCAReichOMedication adherence in patients with diabetes mellitus: does physician drug dispensing enhance quality of care? Evidence from a large health claims database in SwitzerlandPatient Prefer Adherence2016101803180927695299

- RwegereraGMAdherence to anti-diabetic drugs among patients with Type 2 diabetes mellitus at Muhimbili National Hospital, Dar es Salaam, Tanzania- A cross-sectional studyPan Afr Med J20141725225309652

- WabeNTAngamoMTHusseinSMedication adherence in diabetes mellitus and self management practices among type-2 diabetics in EthiopiaN Am J Med Sci20113941842322362451

- ShamsMEBarakatEAMeasuring the rate of therapeutic adherence among outpatients with T2DM in EgyptSaudi Pharm J201018422523223960731

- CramerJAA systematic review of adherence with medications for diabetesDiabetes Care20042751218122415111553

- SchectmanJMNadkarniMMVossJDThe association between diabetes metabolic control and drug adherence in an indigent populationDiabetes Care20022561015102112032108

- LeeWYAhnJKimJHReliability and validity of a self-reported measure of medication adherence in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus in KoreaJ Int Med Res20134141098111023860015

- GeorgeCFPevelerRCHeiligerSThompsonCCompliance with tricyclic antidepressants: the value of four different methods of assessmentBr J Clin Pharmacol200050216617110930969

- StirrattMJDunbar-JacobJCraneHMSelf-report measures of medication adherence behavior: recommendations on optimal useTransl Behav Med20155447048226622919