Abstract

Objectives

Particularly in the Middle East, few studies have explored the attitude of cancer patients and their families toward cancer diagnosis disclosure (CDD). This study was conducted to investigate the preference and attitude of a sample of cancer patients and their families in Saudi Arabia toward CDD.

Methods

We constructed a questionnaire based on previous studies. The questionnaire assessed preference and attitude toward CDD. Participants were recruited from the King Abdullah Medical City, which has one of the largest cancer centers in Saudi Arabia.

Results

Three hundred and four cancer patients and 277 of their family members participated in the study. The patient group preferred CDD more than the family group (82.6% vs 75.3%, P<0.05). This preference is especially more evident toward disclosure of detailed cancer information (status, prognosis, and treatment) (83.6% vs 59.9%, P<0.001). In a binary logistic regression, factors associated with preference toward CDD included having information about cancer (odds ratio [OR] 1.8; 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.15–2.84) and being employed (OR, 1.77; 95% CI, 1–2.82) while being from the patient group was the only factor associated with preference toward detailed cancer information (OR, 3.25; 95% CI, 2.11–5.05). In terms of patient reaction after CDD, “fear” was the attitude expected by the family group more than the patient group (56.3% vs 70.4%, P<0.001) while “acceptance” was the attitude anticipated by the patient group more than the family group (38% vs 15.2%, P<0.001).

Conclusion

Patients preferred CDD and disclosure of related information, while their families were more inclined toward scarce disclosure. Family members seem to experience negative attitudes more than the patients themselves.

Background

For many patients, including cancer patients, preserving patient autonomy is a central component of the patient-centered model.Citation1 The model focuses on active patient participation, values, and needs in order to improve the overall quality of care. It presents a shift from a paternalistic approach in clinical management, to an approach that ensures mutual decision-making between patients and physicians.Citation2 When the patient-centered model has been implemented, studies found improvement in the quality of health care, decrease in costs, and greater satisfaction for health care providers and patients.Citation3,Citation4

Levels of patient autonomy vary significantly around the world. For example, in Eastern cultures, health care providers involve the family in the decision-making process, often without the patient’s consent. Indeed, some patients may know less than their family about their own diagnoses, procedures, and planned interventions.Citation5

In Saudi Arabia, a country with a Middle Eastern culture and a predominately Muslim population, a number of studies found that oncologists often initially disclosed cancer information to the patient’s family, and that the family would then take over decision-making in terms of procedure and medical interventions. However, on the contrary, these studies also found that almost all cancer patients preferred self-disclosure of cancer as well as more active participation in medical decision-making.Citation6–Citation10

Although previous studies in Saudi Arabia examined the attitude of patients toward cancer diagnosis disclosure (CDD), there is a paucity of research exploring family perspectives toward CDD. To our knowledge, there is no study that has explored important aspects related to attitudes of patients and families toward CDD in Saudi Arabia (eg, reasons for disclosure/nondisclosure, patient reaction to CDD, and factors to accept CDD). Our study aims to fill this gap in the literature by examining the perspectives of patients and their families toward CDD, and exploring the factors that influence their attitudes.

Methods

Participants and procedures

The present study involves a cross-sectional survey of cancer patients and their families. Convenience sampling was used. Inclusion criteria were cancer patients aged 18 or above accompanied by family member, based at the Oncology Clinic of the King Abdullah Medical City. Cancer in patients and their accompanied family members were also included in the study. At the time of surveying, the medical city housed 550 beds, providing tertiary care to patients from across Saudi Arabia, although patients were largely from the western coast of the country. All participants in the study were Muslims. Exclusion criteria were lack of capacity to consent and refusal of participation.

In total, 581 individuals (304 cancer patients and 277 family members) were involved in the study. Each individual was given information explaining the study and was asked to verbally consent to participation. Those who accepted were then interviewed by a member of the research team via direct questioning. Patients were first interviewed apart from their families in the waiting area of the oncology outpatient clinic, or in their rooms if they were in patients. Families were then subsequently interviewed by the same research member separately. Twenty-seven family members refused to participate. Reasons for nonparticipation included interruptions due to patient appointments or lack of interest.

Measurements

The study involved the development of a questionnaire examining the attitudes of patients and their family members. The questionnaire was adopted from Farhat et al,Citation11 who attempted to capture religious and social factors influencing decision-making. The questionnaire gathered information on the following: demographic information (age, sex, education level, relationship to patient, and employment status); clinical information (primary cancer type, disease stage, and awareness of cancer diagnosis); attitude toward CDD and factors influencing decision-making, which encompassed the first 16 questions based on the questionnaire from Farhat et al.Citation11 This final point includes information pertaining to preference of CDD, reasons for disclosure and nondisclosure, knowledge about cancer, expected patient reaction when learning about diagnosis, and factors that may help in accepting cancer diagnosis.

Statistical analysis

The study employed descriptive statistics to describe the general demographics of patients and family members. We used an unpaired Student’s t-test or χ2 test to determine significant differences between the patient and family group. In addition, we used binary logistic regression analysis to estimate the odds ratio for three dependent variables: 1) preference of CDD, 2) preference of detailed cancer-related information, and 3) timing of CDD (before or after treatment). The significant level was set at P<0.05. IBM SPSS Statistics 21.0 (IBM Corporation, Armonk, NY, USA) was used for all statistical analyses.

Results

Sample characteristics

Five hundred and eighty-one subjects participated in this study (304 patients and 277 family members). shows the characteristics of the respondents. The patient group consisted of more females (P<0.001), and subjects were older (P<0.001), less educated (P<0.001), and more unemployed (P<0.001) compared to the family group. The patient group were accompanied by children more often than other types of family members (P<0.001), and the majority of the patient group (86.27%) knew about the diagnosis prior to treatment.

Table 1 The characteristics of the subjects

Differences in attitudes toward CDD

Having knowledge about cancer was reported by 54.2% of the patients and 59.5% of their family members. Their sources of information were the media (26.3% and 33.7%, respectively), physicians (28.6% and 18.8%), personal experience (30.6% and 1.4%), and family experience (6.6% and 25%).

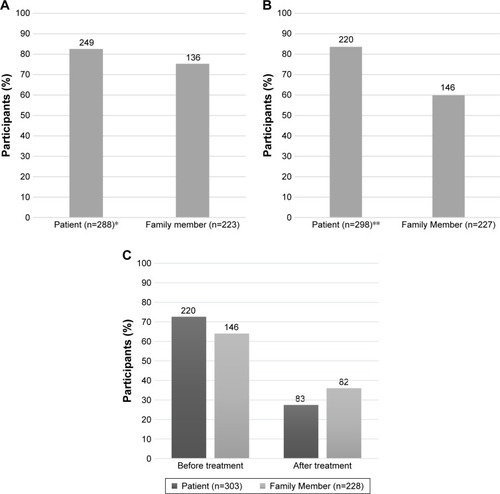

The patient group was more likely to respond that the patient should be informed about the cancer diagnosis than the family group (82.6% vs 75.3%, P<0.05; ); and more likely to respond that the patient should be informed about the details of the cancer status (cancer stage, prognosis, and management) (83.6% vs 59.9%, P<0.001; ). The reasons that participants gave for answering “Yes” or “No” to the questions of disclosure are detailed in .

Figure 1 The percentage of participants who answered “yes” to the following questions: (A) Do you think a patient should be informed about cancer diagnosis? (B) Do you think a patient should be given all the details of his cancer status? (C) When do you think a patient should be informed about cancer? *P<0.05; **P<0.001.

Table 2 Differences in attitudes toward disclosure of cancer diagnosis

The patient group was more likely to respond that the patient should be informed about the cancer diagnosis prior to the start of treatment than the family group (72.9% vs 64%, P<0.05; ). In addition, the patient group was more likely than the family to think that cancer patients can recover from cancer (87.4% vs 75.4%, P<0.001). No significant differences were found between the three questions in and different age groups (<30, 31–50, 51–70 and >70 years) in the patient or the family groups.

Concerning factors that could help individuals accept the cancer diagnosis, nonsignificant differences were observed between the patient and the family groups. Three factors were chosen by both groups as most important: 1) religion, 2) relationship between doctor and patient, and 3) support from family and friends (). In terms of attitude after CDD, fear was most commonly selected by both patient and family groups, although it was chosen more by the family group (56.3% vs 70.4%, P<0.001), while acceptance was chosen more by the patient group (38% vs 15.2%, P<0.001).

Binary logistic regression analyses

This study involved binary logistic regression to explore factors that could contribute to the three questions in . The study analyzed the following: participant group (either patient group or family group), gender, age, education level, having information about cancer, and employment status ().

Table 3 Binary logistic regression analysis predicting disclosure of cancer

For Question 1 as a response variable, having information about cancer and being employed were the only two categories favoring the response variable. While for Question 2 as a response variable, being a patient in the group was the only variable with a significant association. Finally, for Question 3 as a response variable, being a patient, having information about cancer, and being employed were found to significantly predict the response variable.

Discussion

Preference of cancer disclosure

The results of this study confirm patient preference for CDD and related information, as has been shown in previous studies in Saudi Arabia, and around the world.Citation5,Citation7,Citation10,Citation12,Citation13 We add to the literature one more study about the perception toward CDD of patients and their families. Despite the importance of this topic, it has only been investigated by a single recent study, from Zekri et al.Citation10 We found that cancer patients preferred to be informed about the cancer diagnosis more than their families (82.6% vs 75.3%, P<0.05). However, when both patient and family groups were asked about their preferences toward detailed information about cancer status (in terms of cancer stage, prognosis, and management), the gap between group preferences was found to be larger (83.6% vs 59.9%, P<0.001).

Similarly, recent results of a Saudi studyCitation10 found that 52% of patients’ family members, compared with 85% of patients (P<0.001), preferred disclosure of information regarding cancer (diagnosis, possible poor outcome, chemotherapy, failure of treatment, changes in condition and outcome, serious health updates, and lack of specific anticancer treatment options), while the gap between the preferences of both groups was found to be closer when asked about disclosure preference for cancer diagnosis only (patient: 87% vs family: 68%, P<0.001). This gap in preferences may have reflected how much knowledge about the cancer prognosis was provided to cancer patients and their family members in the cancer journey. Moreover, studies from Western and non-Western countriesCitation14,Citation15 found approximately 80% of family members and only 30%–60% of patients were aware when the cancer had become terminal.Citation16 In conclusion, this may indicate the tendency of family members to prefer disclosure of scarce cancer-related information to cancer patients.

Reasons for disclosure and nondisclosure

Part of the explanation of the family group preference of scarce information to the patient, in our study, can also be contributed to the reasons that they chose for nondisclosure. Among the reasons for nondisclosure, preventing a negative effect on the patient (77%) emerged as the most popular. This may reflect the intention of family members to protect cancer patients from psychological distress, which is thought to be the most important factor for preference of nondisclosure.Citation17,Citation18 A recent study completed in Egypt, a country with a similar culture to Saudi Arabia,Citation19 found that family members who preferred a nondisclosure of cancer diagnosis to patients also responded that they would prefer not to know their own cancer diagnosis in the event that they developed cancer. This may reflect their own fear of psychological distress.

The three reasons for cancer disclosure in our study were as follows: helping patient’s treatment, organizing their lives, and avoiding living under an illusion. These reasons were selected by both the patients and their family members more than any other reasons. In essence, these are among the main benefits of CDD to patients; taken collectively, they improve the patient’s quality of life. A recent study indicated that patients who were informed about their cancer treatment were found to have better health competence, a greater sense of control over cancer, and improved symptom management.Citation20 On the contrary, noninformed patients were found to have higher levels of anxiety and irritability than informed patients.Citation21

Important factors in acceptance of cancer disclosure

In response to questions concerning the factors that help patients and family members accept cancer conditions, religion (91%), relationship between doctor and patient (patient: 87.4% vs family: 89.2%), and support from family and friends (patient: 85.1% vs family: 90.5%) were the three factors chosen more than any others. Religion is a fundamental influence for the decision-making of Muslims. A recent studyCitation22 found that 74.3% of Muslim patients with colorectal cancer responded that their entire approach to life was based on religious beliefs. In another study, 90% of medical patients reported that religious beliefs helped them to cope with their illness.Citation23 This religious background may have led 91% of our participants to select religion as a key factor for accepting a cancer diagnosis. However, further exploration of religion as a contributing factor in acknowledging cancer diagnosis is warranted.

The result that the relationship between doctor and patient is one of the most important factors in accepting a cancer diagnosis aligns with recent studies that have found an association between doctor–patient communication and cancer patient outcomes, especially satisfaction, psychological morbidity, and understanding.Citation24 In regard to the support of family and friends, the Middle Eastern cultural and religious values of participants encourage them to provide support to their relatives in need.Citation7

Patient reaction to disclosure and cure rate

Concerning patient reaction to cancer disclosure, negative emotions (denial, fear, anger, and sadness) were expected by families to emerge, more than what patients expected themselves. This is particularly true for fear, as our study found statistical differences between the two groups (patients: 56.3% vs families: 70.4%, P<0.001). Indeed, many studies have found cancer to be the most feared disease.Citation25,Citation26

A recent study in LebanonCitation11 found that both patient and family groups expected fear (33%) as the first reaction of the patient to cancer disclosure with nonsignificant differences. The study found fear to be the most difficult feeling a cancer patient may have to experience (63% of all participants).Citation11 On the other hand, acceptance, a positive emotion was expected by patients more than their families (38% vs 15.2%, P<0.001).

In addition to this, family members not only expected patients to show negative emotions but also they were more negative in terms of recovery rate (families: 75.4% vs patients: 87.4%, P<0.001). These findings may indicate that the family is more pessimistic than the patient group toward the cancer treatment, or that the patient group is more hopeful and optimistic than the family.

Study limitations

Our study had several limitations. First, we used convenient sampling. Using probability sampling method would have been a better method, especially if the patients and family members were matched based on time since cancer diagnosis, extent of cancer knowledge, or relation to patient. Second, the family members accompanying the patients might not have been representative of all family members. Finally, participants were recruited from only one hospital.

Clinical implications

This study indicates the preference of families toward nondisclosure attitudes for cancer diagnosis.Citation5,Citation10,Citation12 It also shows the tendency of families to disclose only limited cancer information as the disease progresses. Therefore, physicians need to be vigilant in discerning how much information cancer patients actually possess throughout the treatment process.

To ease the nondisclosure attitude of family members of cancer patients in non-Western cultures, we suggest addressing any fears that families may have on causing psychological distress on the patients. As we mentioned earlier, this reason is thought to be the most important factor for nondisclosure,Citation18 and was the most popular selection among other reasons in our sample. This can be facilitated by utilizing physician–patient communication protocols described in the literature – one of the most renowned is the SPIKES protocolCitation27 – as well as applying suggested approaches for culturally competent communication.Citation28,Citation29 Finally, we recommend educating families about the benefits of well-informed patients, which include, among other things, better health competence, greater sense of control over cancer, and improved symptom management.Citation20

Conclusion

This study provides insight into the attitude of cancer patients and their families toward cancer diagnosis in a sample of participants from Saudi Arabia. We found that most patients preferred full disclosure of all details of their cancer treatment, while families were more inclined to providing scarce information. Fear and pessimistic expectations toward cancer disclosure and its management characterized the experience of family members, but was less common among patients. Ultimately, we proposed that the physician–patient relationship and family support play a crucial role in facilitating CDD and its related information. The findings of this study, concerning patient and family preferences and attitudes, can be utilized to provide more effective cancer treatment.

Ethical approval

The study took place over the period between June 2016 and February 2017. The study and verbal consent process was approved by the Institutional Review Board of King Abdullah Medical City (number 16–259).

Acknowledgments

Data were presented at the 13th International Conference on Psychiatry (Controversies in Diagnosis and Treatment in Psychiatry: Professional Experiences), Jeddah, Saudi Arabia, April 13–14, 2017.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- EpsteinRMStreetRLJrPatient-Centered Communication in Cancer Care: Promoting Healing and Reducing SufferingBethesda, MDNational Cancer Institute2007

- Institute of Medicine, Committee on the National Quality Report on Health Care DeliveryCrossing the Quality Chasm: A New Health System for the 21st CenturyHurtadoMSwiftECorriganJWashington, DCThe National Academies Press2001

- BertakisKDAzariRPatient-centered care is associated with decreased health care utilizationJ Am Board Fam Med201124322923921551394

- StewartMBrownJBDonnerAThe impact of patient-centered care on outcomesJ Fam Pract200049979680411032203

- MobeireekAFAl-KassimiFAl-ZahraniKInformation disclosure and decision-making: the Middle East versus the Far East and the WestJ Med Ethics200834422522918375670

- Al-AmriAMCancer patients’ desire for information: a study in a teaching hospital in Saudi ArabiaEast Mediterr Health J2009151192419469423

- AljubranAHThe attitude towards disclosure of bad news to cancer patients in Saudi ArabiaAnn Saudi Med201030214114420220264

- Al-MohaimeedAASharafFKBreaking bad news issues: a survey among physiciansOman Med J2013281202523386940

- MobeireekAFAl-KassimiFAAl-MajidSAAl-ShimemryACommunication with the seriously ill: physicians’ attitudes in Saudi ArabiaJ Med Ethics19962252822858910780

- ZekriJKarimSMBreaking cancer bad news to patients with cancer: a comprehensive perspective of patients, their relatives, and the public – example from a Middle Eastern countryJ Glob Oncol20162526827428717713

- FarhatFOthmanAEl BabaGKattanJRevealing a cancer diagnosis to patients: attitudes of patients, families, friends, nurses, and physicians in Lebanon-results of a cross-sectional studyCurr Oncol2015224264272

- SurboneATelling the truth to patients with cancer: what is the truth?Lancet Oncol200671194495017081920

- Al-AmriAMDisclosure of cancer information among Saudi cancer patientsIndian J Cancer201653461561828485365

- AabomBKragstrupJVondelingHBakketeigLSStovringHDefining cancer patients as being in the terminal phase: who receives a formal diagnosis, and what are the effects?J Clin Oncol200523307411741616157932

- CherlinEFriedTPrigersonHGSchulman-GreenDJohnson- HurzelerRBradleyEHCommunication between physicians and family caregivers about care at the end of life: when do discussions occur and what is said?J Palliat Med2005861176118516351531

- YunYHKwonYCLeeMKExperiences and attitudes of patients with terminal cancer and their family caregivers toward the disclosure of terminal illnessJ Clin Oncol201028111950195720212258

- MystakidouKParpaETsililaEKatsoudaEVlahosLCancer information disclosure in different cultural contextsSupport Care Cancer200412314715415074312

- ShahidiJNot telling the truth: circumstances leading to concealment of diagnosis and prognosis from cancer patientsEur J Cancer Care2010195589593

- AlsirafySAAbdel-KareemSSIbrahimNYAbolkasemMAFaragDECancer diagnosis disclosure preferences of family caregivers of cancer patients in EgyptPsychooncology201726111758176227362334

- HussonOMolsFvan de Poll-FranseLVThe relation between information provision and health-related quality of life, anxiety and depression among cancer survivors: a systematic reviewAnn Oncol201122476177220870912

- HorikawaNYamazakiTSagawaMNagataTThe disclosure of information to cancer patients and its relationship to their mental state in a consultation-liaison psychiatry setting in JapanGen Hosp Psychiatry199921536837310572779

- Shaheen Al AhwalMAl ZabenFSehloMGKhalifaDAKoenigHGReligious beliefs, practices, and health in colorectal cancer patients in Saudi ArabiaPsychooncology201625329229925990540

- KoenigHGReligious attitudes and practices of hospitalized medically ill older adultsInt J Geriatr Psychiatry19981342132249646148

- UitterhoeveRJBensingJMGrolRPDemulderPHvan AchterbergTThe effect of communication skills training on patient outcomes in cancer care: a systematic review of the literatureEur J Cancer Care2010194442457

- BeachWAEasterDWGoodJSPigeronEDisclosing and responding to cancer “fears” during oncology interviewsSoc Sci Med200560489391015571904

- ClarkeJNEverestMMCancer in the mass print media: fear, uncertainty and the medical modelSoc Sci Med200662102591260016431004

- BaileWFBuckmanRLenziRGloberGBealeEAKudelkaAPSPIKES – a six-step protocol for delivering bad news: application to the patient with cancerOncologist20005430231110964998

- HallenbeckJArnoldRA request for nondisclosure: don’t tell motherJ Clin Oncol200725315030503417971606

- Matthews-JuarezPWeinbergACultural Competence in Cancer Care: A Health Professional’s PassportRockville, MDOffice of Minority Health, US Department of Health & Human Services2004