Abstract

Purpose

To identify the use pattern of complementary and alternative medicine (CAM) and its impact on antiepileptic drug (AED) adherence among patients with epilepsy.

Method

Potential studies were identified through a systematic search of Scopus, Science Direct, Google Scholar, and PubMed. The keywords used to identify relevant articles were “adherence,” “AED,” “epilepsy,” “non-adherence,” and “complementary and alternative medicine.” An article was included in the review if the study met the following criteria: 1) conducted in epilepsy patients, 2) conducted in patients aged 18 years and above, 3) conducted in patients prescribed AEDs, and 4) patients’ adherence to AEDs.

Results

A total of 3,330 studies were identified and 30 were included in the final analysis. The review found that the AED non-adherence rate reported in the studies was between 25% and 66%. The percentage of CAM use was found to be between 7.5% and 73.3%. The most common reason for inadequate AED therapy and higher dependence on CAM was the patients’ belief that epilepsy had a spiritual or psychological cause, rather than primarily being a disease of the brain. Other factors for AED non-adherence were forgetfulness, specific beliefs about medications, depression, uncontrolled recent seizures, and frequent medication dosage.

Conclusion

The review found a high prevalence of CAM use and non-adherence to AEDs among epilepsy patients. However, a limited number of studies have investigated the association between CAM usage and AED adherence. Future studies may wish to explore the influence of CAM use on AED medication adherence.

Video abstract

Point your SmartPhone at the code above. If you have a QR code reader the video abstract will appear. Or use:

Introduction

Epilepsy is a chronic, non-communicable disorder of the brain that could affect people of any age. Approximately 50 million people worldwide have epilepsy, making it one of the most common neurological diseases globally.Citation1 Most seizures can be controlled with antiepileptic drugs (AEDs). Surgery to remove the epileptogenic lesion may also stop seizure activity. A ketogenic (high-fat, low-carbohydrate) diet may be used to treat epilepsy (recurrent seizures) in children, particularly if seizure medicines are not effective.Citation2

CAM is sought by PWE as an alternative treatment option although its effectiveness has not been clearly established using scientific methods. CAM can be defined as “a broad domain of healing resources that encompasses all health systems, modalities, and practices, and their accompanying theories and beliefs, other than those intrinsic to the politically dominant health systems of a particular society or culture in a given historical period”.Citation3 CAM is reported to be used worldwide.Citation4–Citation6 In various Asian and African countries, CAM is the primary method of health care.Citation7 Over the last decade, the interest in CAM has increased rapidly.Citation8

Based on the National Center for Complementary and Alternative Medicine (NCCAM, 2005), CAMs are broadly divided into five types: biological, spiritual/mind-body, alternative, physical (body-based), and energy therapies.Citation9 Biological methods, also known as natural products, include herbs, vitamins, dietary supplements, antioxidants, and minerals while mind and body practices include acupuncture, aromatherapy, cupping, massage, prayer for health (use of holy water, amulets, or talismans) and Zumba. Alternative medicine includes traditional medicines that vary from region to region, eg, traditional Chinese, Malay, Indian (Ayurvedic/Siddha/Unani) medicines and homeopathy.Citation9,Citation10

The use of CAMs may vary due to differences in cultural norms and healthcare settings. A study performed in Malaysia demonstrated that 71.2% of respondents admitted to CAM use and the use of herbal products was the most popular CAM. The main reason for CAM use was recommendations from family and friends.Citation11

Medication adherence or the older term, drug compliance, is defined as the extent to which patients follow the instructions they are given for prescribed treatments, and their persistence in completing the duration of time from initiation to discontinuation of therapy.Citation12 Usually, measurements of medication adherence are classified by the WHO as subjective and objective measurements.Citation13 Subjective measurements include those requiring the patient’s evaluation of their medication-taking behavior. Self-reported questionnaires, eg, MMAS, and healthcare professional assessments are the most common tools used to assess medication adherence.Citation14 Objective measures include pill counts, secondary database analysis such as the MPR, electronic monitoring, and biochemical measures.Citation15 According to the WHO, the prevalence of AED adherence in developing countries ranges between 20% and 80%.Citation16 In Malaysia, the prevalence of poor adherence to AEDs was documented in 64.1% of PWE, which is higher than the percentages reported in studies conducted in western populations.Citation17

The four primary factors related to medication non-adherence are patient-related factors (eg, socioeconomic characteristics, and perceptions and beliefs), illness-related factors (eg, severity of illness and frequency of symptoms), medication-related factors (eg, number of daily doses, efficacy, and side effects), and physician-related factors (eg, patient-physician relationship).Citation18–Citation21 In a study performed in Malaysia, a busy lifestyle, forgetfulness, younger age, adverse effects of drugs, and limited contact time with a physician were identified as factors affecting adherence.Citation17

Medication non-adherence is a serious issue in PWE and the belief that epilepsy has a spiritual or psychological cause may contribute to inadequate AED therapy and higher dependence on CAM, which can result in AED non-adherence. There is inadequate data on the impact of CAM on adherence among PWE. The purpose of this study was to determine the use pattern and impact of CAM on AED adherence among PWE.

Methods

Studies were identified through a comprehensive literature search of Scopus, Ovid, Medline, Science Direct, Google Scholar, and PubMed from the inception of these sources until May 2018. The keywords used for searching for relevant articles were “adherence,” “compliance,” “AED,” “epilepsy,” “non-adherence,” “CAM,” and “complementary and alternative medicine.” Boolean operators such as ‘AND’ and ‘OR’ were used to increase the sensitivity and specificity of the search when needed. The articles identified were then screened based on the inclusion and exclusion criteria presented in . Initial titles/abstracts were screened by MJF. The exclusion process, using the title/abstract, was also performed by MJF if the reason for exclusion was clear. If there was uncertainty, the article was not excluded and was reviewed by MMB. Any disagreements on whether a study should be included/excluded were resolved through consensus. Data were extracted from a full-text report using a data extraction form, which included study characteristics, participant characteristics, rate of medication adherence, and adherence assessment methods. The primary outcomes of the current study were the rate of patients’ adherence to AEDs, CAM use, and impact of CAM on AED adherence. The quality of the studies was assessed for potential bias by using the evaluation tool for quantitative research studies.Citation22

Table 1 Criteria for inclusion and exclusion of studies in the review

Results

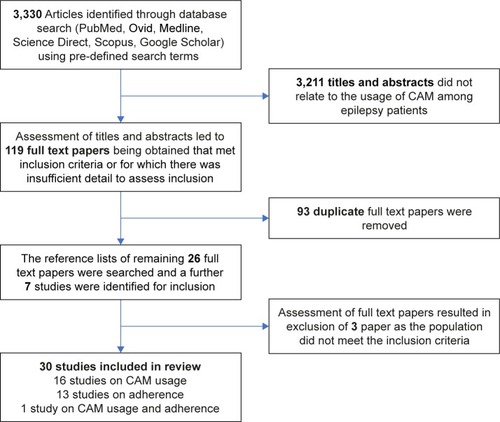

A total of 3,330 titles were retrieved and of this 93 were removed due to duplication. The remaining articles were screened for inclusion and exclusion criteria. Thirty studies were included in the final review. shows the flow of study identification.

Figure 1 Flow diagram of searches and inclusion assessment of studies.

Of the 30 studies, 16 focused on CAM usage among PWE, 13 reported medication adherence, and only one investigated CAM usage and patients’ adherence to AEDs. The types of study design and country settings have been summarized in –.

Table 2 Prevalence and types of CAM use

Table 5 CAM usage and adherence among epilepsy patients

Prevalence and types of CAM usage

In the 16 papers identified, the prevalence of CAM use was between 7.5% and 73.3%. The use of CAM in developed countries was higher than that in the developing countries. However, the types of CAM used did not differ much, with some variation due to differences in cultural and traditional norms. The most prevalent type of CAMs reported in these studies were herbal (n=6), prayer/spirituality (n=5), and yoga/exercise (n=5).

The belief that epilepsy has a spiritual or psychological cause, rather than being a primary ailment of the brain contributes to inadequate AED therapy and higher dependence on CAM, which results in inadequate AED treatment.Citation23

In developed countries, CAM treatments are frequently used for overall wellness or for chronic conditions, for instance, epilepsy or pain, that respond inadequately to standard treatments.Citation24 In Western Europe and North America, regardless of availability and accessibility to advanced technology and evidence-based allopathic medicine, CAM is expanding in terms of its economic importance as a treatment choice for many health care needs.Citation25 In most of the studies performed in the USA, yoga, botanicals (herbs), prayer/spirituality, vitamins, and stress reduction were the most frequently used methods in PWE.Citation8,Citation26,Citation27 Majority of the patients did not disclose the use of CAM to their doctors.Citation8,Citation28 In one survey among PWE in the USA, the most commonly used herbs were ginseng, St John’s wort, ginkgo (Ginkgo biloba), and garlic.Citation29 These results were consistent with those of a study that showed that garlic and ginkgo were most frequently used by PWE.Citation30

Use of amulets, prayer for health, and visits to faith healers were common among Islamic countries.Citation31–Citation34 Some types of CAM are more specific to a region and may vary between countries. The use of Ayurvedic medicine has been reported in several studies in India.Citation35–Citation37 In Taiwan, traditional Chinese medicine is quite prevalent since it was established in China about 3,000 years ago.Citation38 The Taiwanese have been greatly influenced by Chinese culture. Many Taiwanese believe that worship can cure an illness.Citation39 The prevalence and types of CAM used in developed and developing countries are summarized in .

Factors and reasons associated with CAM use

Among 16 papers identified, only eight papers reported the reasons for CAM use. The most commonly reported factors included fear of AED-related side effects (n=4)Citation31,Citation33–Citation36,Citation40 and poor seizure control (n=3).Citation28,Citation39,Citation40 Two studies reported the influence of family members as the reason for CAM usage.Citation35,Citation40

It is worthwhile to note that patients attributed their epilepsy to factors outside the realm of a biomedical model, including spirit possession (Jinn), evil eyes, contemptuous envy, or sorcery.Citation32,Citation41 Therefore, it seems consistent that most people adhere to a holistic perspective or to scriptural teaching (Holy Qur’an) as a health aid to their epilepsy. In addition to being a health aid, it is possible that CAM is used to reduce social stigma. For example, in Oman, the presence of hyper salivation and belief in spirits as the causes of epilepsy were strong predictors of CAM use.Citation34

Prevalence of medication non-adherence among PWE

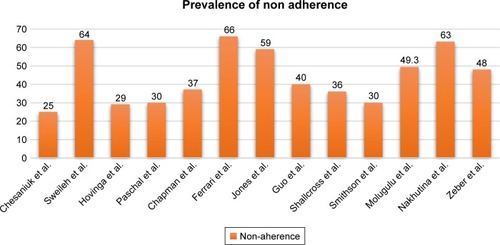

The prevalence of non-adherence in 13 studies ranged between 25% and 66% as shown in . The overall adherence level in western countries was higher than that in Asian counties. This reflects that people living in developing countries prefer traditional medicines to modern allopathic medicines, which may lead to non-adherence.

Figure 2 Outlines AED non-adherence rates for thirteen studies.

Many adherence calculation methods were used across the included studies.Citation42–Citation45 The MMAS was used in four surveys.Citation44–Citation47 Two studies used the MMAS-4 tool and two studies used the MMAS-8.Citation45,Citation47 Hovinga et al used a 1-month recall period method to measure adherence.Citation48 Two studies used a mixed-method approach using two items from the Epilepsy Self-Management Scale along with the MPR tool. MPR scores were determined using the participants’ medication records in both these studies.Citation42,Citation49 MPR was determined by dividing the number of days on which medication was available by the number of days between the earliest prescription claims in the observation period through the end of the observation period with a threshold of <0.80 defining non-adherence.Citation50 The prevalence of non-adherence and methods of assessment across all the 13 studies have been listed in .

Table 3 Prevalence of adherence and methods of assessment

Factors associated with non-adherence

Factors associated with medication non-adherence across the 13 studies are outlined in . In two studies, perceptions of barriers, lack of motivation to take medication, fear of adverse effects, and knowledge gap were reported to be the causes for medication non-adherence among PWE.Citation51,Citation52 Others factors such as difficulty in opening container lids or shortage of medication in the market were also reported to cause AED non-adherence.Citation51,Citation53

Table 4 Factors associated with medication non-adherence

Patient-related factors

In four of the included studies, females were reported to be more likely to comply with AEDs.Citation44,Citation45,Citation48,Citation49 Depression and anxiety were associated with poor adherence in two studies.Citation45,Citation47 In one study, a significant difference in depression scores was reported between the low and the moderate-to-high adherence groups (P<0.001).Citation45 Four studies reported forgetfulness as the reason for AED non-adherence.Citation44,Citation48,Citation51,Citation54

Illness-related factors

Four studies investigated the associations between adherence and seizure control.Citation44,Citation46,Citation48,Citation55 Ferrari et al reported no significant association between seizure control and adherence to medication.Citation44 Other three studies demonstrated a strong correlation between poor seizure control and non-adherence.Citation46,Citation48,Citation55

Medication-related factors

The most significant medication-related factors associated with non-adherence included missed doses, poly pharmacy, high cost, and medication side effects.Citation44,Citation48,Citation56,Citation57 In the study by Ferrari et al, 45% of patients who received mono therapy showed high treatment adherence while the rest showed moderate-to-low adherence.Citation44 Nevertheless, Guo et al reported that non-adherence to AED had no significant association with mono/poly therapy (P>0.05).Citation45 AED unavailability (48%) was the major factor leading to non-adherence.Citation23

Physician-related factors

One study investigated the impact of the patient-physician relationship and found that trust in doctors was more prevalent among adherent patients (34%) compared to that in non-adherent patients (17%). Furthermore, adherent participants reported being comfortable while disclosing missed medications to their doctor (27% vs 12%).Citation48 Other studies did not indicate the patient-physician relation and its impact on adherence.

Impact of CAM on adherence and AED therapy

There seemed to be a deficiency of clinical evidence about AED non-adherence and CAM use. However, Durón et al assessed adherence to AEDs and CAM use and found non-adherence to AED in 121 patients, with the unavailability of AEDs (48%) being the most common reason for non-adherence and prayer, herbs, and potions being the common CAMs used as shown in . Among 51.5% of CAM users, 44.2% reported that they had stopped taking their AEDs.Citation23

Quality of included studies

Quality varied across the studies included. The response rate varied from 11% to 79.5%. Nine studies did not report response rates.Citation28,Citation31,Citation33,Citation39,Citation40,Citation46,Citation47,Citation56,Citation58 The manner in which par ticipants were recruited and the sample size was determined were not clearly reported in seven studies.Citation28,Citation29,Citation31,Citation40,Citation46,Citation54 Types of CAM used were not explained in two studies.Citation28,Citation40 Patients’ adherence to medication was mostly assessed using the MMAS (n=6).Citation44–Citation47,Citation56,Citation57 Three studies did not clearly explain how medication adherence was measured.Citation48,Citation54,Citation55

Discussion

In the current study, we reviewed the use pattern and impact of CAM on AED adherence among PWE. We included 30 studies in this review and a particular concern was the low response rate in the included surveys. The variable methodological quality of many included studies is identified as a study limitation. Nine studies did not report the response rate. Further problems with surveys of CAM were related to the fact that no universally accepted definition of CAM exists. This means that different surveys monitor the use of different methods. Self-reported questionnaires typically provide overestimates of adherence for several reasons: first, they may rely on patients’ own interpretation or memory of what advice was given and, if accepted, how closely it has been followed; and second, patients may tend to report higher levels of adherence in order to please health care providers or avoid embarrassment.Citation59 CAM therapies for epilepsy in developing countries have evolved over the centuries, often in conjunction with the health care system, education level, and changing cultural beliefs.Citation40 The use of CAM in developed countries was higher than that in developing countries, with some variation due to the difference in cultural and traditional norms.

The most prevalent types of CAM reported in the studies reviewed were the use of herbal products, prayer/spirituality, and yoga/exercise. Fear of AED-related side effects and poor seizure control were the most frequently reported reasons for using CAM. Although pharmacological treatments of epilepsy have been shown to be efficacious in mitigating various types of epilepsies, the side effects of these medications result in adverse effects on the patients’ quality of life, often resulting in poor compliance.Citation57 This is likely to contribute to a shift toward the use of CAM among PWE.Citation44 Studies have shown that many PWE tend to concurrently use both CAM and antiepileptic medication. This may be due to attractive marketing strategies used by herbal and vitamin companies that make claims of the safety and benefits of CAM, which attract patients; however, there is limited scientific evidence of their efficacy and safety in epilepsy.Citation60 Some studies have further shown that some PWE tend not to disclose their use of CAM to their health care providers working under the auspices of biomedical care.Citation48

In several countries, it is believed that epilepsy is linked to supernatural or spiritual causes, which may lead to under-treatment and greater reliance on CAM use.Citation26,Citation40,Citation61 In these countries, it is believed that diseases caused by supernatural things cannot be cured with allopathic medicine and CAM should be used to treat such patients.Citation26,Citation31,Citation40 Cultural views complicate the issue of medication non-adherence.Citation23,Citation61,Citation62 Patients prefer CAM assuming that spirit possession is the cause of epilepsy and they seldom consider AEDs as the primary therapy.Citation23 In many surveys, a significant percentage of PWE used CAM.Citation26,Citation40,Citation61 Surveys conducted in multicultural regions show that vitamins, prayer for health, and stress management are the most frequently used types of CAM.Citation23,Citation26,Citation63 Patients who associated epilepsy with non-biological causes, such as spirits and exorcism, often visited faith healers before going to a doctor which led to under-treatment and greater reliance on CAM usage.Citation34 These findings indicate the need for educating people and spreading awareness regarding epilepsy and the role of AEDs in the treatment of epilepsy.Citation34 However, there is no direct evidence from the reviewed literature that belief in the spiritual nature of epilepsy affects AED adherence. Further studies are needed to check the association of spiritual belief and AED adherence.

The prevalence of AED non-adherence was reported in 13 of the studies and ranged between 25% and 66%. However, the assessment methods used in these studies were mainly subjective (patient-reported questionnaires) and tended to overestimate patient adherence. Using a mixed-method approach (ie, using subjective and objective assessment tools), patient adherence can be more effectively estimated. Forgetfulness, specific beliefs about medications, depression, uncontrolled recent seizures, frequent medication dosage times and poly pharmacy were the most frequently reported factors associated with AED non-adherence. Similar findings were reported in a study where people using poly therapy were more likely to forget to take their medication.Citation70

Pharmacists should conduct counseling and educational programs to help patients improve medication adherence and change their false perception about the etiology of epilepsy. A study showed that the level of knowledge could possibly influence the levels of adherence to medications, and pharmacists could play a more active role in ensuring proper information is disseminated based on the education level of the patients.Citation64 These findings are consistent with those of a study in which the compliance rate was high among patients with good knowledge about their disease.Citation65 Furthermore, the use of various compliance aids such as pill boxes, medication reminders, and combination therapy (where possible) to reduce the number of pills can improve adherence.Citation66 Since depression may reduce patients’ adherence to medication, lower rates of depression may be associated with better medication adherence.Citation67 Organizational religious activity had a significant positive association with adherence to medications and it can lower depression.Citation68,Citation69

Although many studies have reported the reasons for CAM usage among PWE, there seemed to be limited evidence on AED non-adherence due to CAM usage.Citation23 Among the 30 studies included in this review, the association between AED adherence and CAM use was assessed in only one study.Citation23 More studies should be performed to investigate the resultant effects of CAM use by PWE to gather detailed information on whether the treatment under consideration has a positive or negative impact on the patient’s health condition and adherence to AED.

Conclusion

Medication non-adherence is associated with forgetfulness, shortage of medication, cultural beliefs, and the use of CAMs instead of AEDs. An intensive education program should be the priority for changing patients’ beliefs. Awareness should be raised regarding the etiology of epilepsy and effectiveness of AEDs in treating epilepsy. Governments and pharmaceutical industries need to collaborate to access, obtain, store, and distribute AEDs effectively. Moreover, further studies are needed to investigate the effects of CAM in epilepsy and its impact on medication adherence, to provide insight into whether or not the treatments being used are beneficial since the studies comparing the impact of CAM on adherence and AED therapy are limited.

Author contributions

All authors contributed to data analysis, drafting and revising the article, gave final approval of the version to be published, and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Abbreviations

| AED | = | antiepileptic drug therapy |

| CAM | = | complementary and alternative medicine |

| MMAS | = | Morisky Medication Adherence Scale |

| MPR | = | medication possession ratio |

| PWE | = | patients with epilepsy |

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- WHOEpilepsy Fact Sheet2016 Available from: http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs999/en/AccessedMarch 20, 2018

- MarksWJGarciaPAManagement of seizures and epilepsyAm Fam Physician19985771589160316001604

- ZollmanCVickersAABC of complementary medicine: What is complementary medicine?BMJ1999319721169369610480829

- ShaikhSHMalikFJamesHAbdulHTrends in the use of complementary and alternative medicine in Pakistan: a population-based surveyJ Altern Complement Med200915554555019422284

- FoxPCoughlanBButlerMKelleherCComplementary alternative medicine (CAM) use in Ireland: a secondary analysis of SLAN dataComplement Ther Med20101829510320430292

- AydinSBonkayaAOMaziciogluMMGemalmazAOzturkAWhat influences herbal medicine use?-prevalence and related factorsTurk J Med Sci2008385455463

- JeongMJLeeHYLimJHYunYJCurrent utilization and influencing factors of complementary and alternative medicine among children with neuropsychiatric disease: a cross-sectional survey in KoreaBMC Complement Altern Med20161619126931188

- SirvenJIDrazkowskiJFZimmermanRSComplementary/alternative medicine for epilepsy in ArizonaNeurology200361457657712939447

- WielandLSManheimerEBermanBMDevelopment and classification of an operational definition of complementary and alternative medicine for the Cochrane collaborationAltern Ther Health Med201117250

- RhodesPJSmallNIsmailHWrightJPThe use of biomedicine, complementary and alternative medicine, and ethnomedicine for the treatment of epilepsy among people of South Asian origin in the UKBMC Complement Altern Med200881718366698

- JasamaiMIslahudinFSamsuddinNFAttitudes towards complementary alternative medicine among Malaysian adultsJ Appl Pharm Sci2017706190193

- ShamsMEBarakatEAMeasuring the rate of therapeutic adherence among outpatients with T2DM in EgyptSaudi Pharm J201018422523223960731

- WHOAdherence to long-term therapies: evidence for action2003 Available from: http://www.who.int/chp/knowledge/publications/adherence_report/en/Accessed March 29, 2018

- VelliganDIWangMDiamondPRelationships among subjective and objective measures of adherence to oral antipsychotic medicationsPsychiatr Serv20075891187119217766564

- VermeireEHearnshawHvan RoyenPDenekensJPatient adherence to treatment: three decades of research. A comprehensive reviewJ Clin Pharm Ther200126533134211679023

- WHOAdherence to Long-term Therapies: Evidence For ActionGenevaWorld Health Organization2003 http://www.who.int/chp/knowledge/publications/adherence_report/en/Accessed September 14, 2018

- TanXMakmor BakryMLauCTajarudinFRaymondAFactors affecting adherence to antiepileptic drugs therapy in MalaysiaNeurol Asia2015203235241

- Buck DJacobyAJacobyABakerGAChadwickDWFactors influencing compliance with antiepileptic drug regimesSeizure19976287939153719

- ScottJPopeMNonadherence with mood stabilizers: prevalence and predictorsJ Clin Psychiatry200263538439012019661

- GreenhouseWJMeyerBJohnsonSLCoping and medication adherence in bipolar disorderJ Affect Disord200059323724110854641

- KleindienstNGreilWAre illness concepts a powerful predictor of adherence to prophylactic treatment in bipolar disorder?J Clin Psychiatry200465796697415291686

- LongAFGodfreyMRandallTBrettleAGrantMJHCPRDU evaluation tool for quantitative studies, University of Leeds, Nuffield Institute for Health, Leeds Available from: http://usir.salford.ac.uk/12969/Accessed March 20, 2018

- DurónRMMedinaMTNicolásOAdherence and complementary and alternative medicine use among Honduran people with epilepsyEpilepsy Behav200914464565019435580

- Wahner-RoedlerDLElkinPLVincentAUse of complementary and alternative medical therapies by patients referred to a fibro-myalgia treatment program at a tertiary care centerMayo Clin Proc2005801556015667030

- AzaizehHSaadBCooperESaidOTraditional Arabic and Islamic medicine, a re-emerging health aidEvid Based Complement Alternat Med20107441942418955344

- LiowKAblahENguyenJCPattern and frequency of use of complementary and alternative medicine among patients with epilepsy in the midwestern United StatesEpilepsy Behav200710457658217459780

- McconnellBVApplegateMKenistonAKlugerBMaaEHUse of complementary and alternative medicine in an urban county hospital epilepsy clinicEpilepsy Behav201434737624726950

- EasterfordKCloughPComishSLawtonLDuncanSThe use of complementary medicines and alternative practitioners in a cohort of patients with epilepsyEpilepsy Behav200561596215652735

- PeeblesCTMcauleyJWRoachJMooreJLReevesALAlternative medicine use by patients with epilepsyEpilepsy Behav200011747712609128

- HarmsSLGarrardJSchwinghammerPEberlyLEChangYLeppikIEGinkgo biloba use in nursing home elderly with epilepsy or seizure disorderEpilepsia200647232332916499756

- PalSKSharmaKPrabhakarSPathakAPsychosocial, demographic, and treatment-seeking strategic behavior, including faith healing practices, among patients with epilepsy in northwest IndiaEpilepsy Behav200813232333218550440

- RazaliSMYassinAMComplementary treatment of psychotic and epileptic patients in malaysiaTranscult Psychiatry200845345546918799643

- Asadi-PooyaAAEmamiMPerception and use of complementary and alternative medicine among children and adults with epilepsy: the importance of the decision makersActa Med Iran201452215324659074

- Al AsmiAAl ManiriAAl-FarsiYMTypes and sociodemographic correlates of complementary and alternative medicine (CAM) use among people with epilepsy in OmanEpilepsy Behav201329236136624011398

- TandonMPrabhakarSPandhiPPattern of use of complementary/alternative medicine (CAM) in epileptic patients in a tertiary care hospital in IndiaPharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf200211645746312426930

- BhaleraoMSBolshetePMSwarBDUse of and satisfaction with complementary and alternative medicine in four chronic diseases: a cross-sectional study from India20132627578

- NaveenGHSinhaSGirishNTalyABVaramballySGangadharBNYoga and epilepsy: What do patients perceive?Indian J Psychiatry201355Suppl 3S39024049205

- LiQChenXHeLZhouDTraditional Chinese medicine for epilepsyCochrane Database Syst Rev20093CD006454

- KuanYCYenDJYiuCHTreatment-seeking behavior of people with epilepsy in Taiwan: a preliminary studyEpilepsy Behav201122230831221813332

- KimIJKangJKLeeSAFactors contributing to the use of complementary and alternative medicine by people with epilepsyEpilepsy Behav20068362062416530015

- ObeidTAbulabanAAl-GhataniFAl-MalkiARAl-GhamdiAPossession by ‘Jinn’ as a cause of epilepsy (Saraa): a study from Saudi ArabiaSeizure201221424524922310171

- ChapmanSCHorneRChaterAHukinsDSmithsonWHPatients’ perspectives on antiepileptic medication: relationships between beliefs about medicines and adherence among patients with epilepsy in UK primary careEpilepsy Behav20143131232024290250

- EttingerABGoodMBManjunathREdward FaughtRBancroftTThe relationship of depression to antiepileptic drug adherence and quality of life in epilepsyEpilepsy Behav20143613814324926942

- FerrariCMde SousaRMCastroLHFactors associated with treatment non-adherence in patients with epilepsy in BrazilSeizure201322538438923478508

- GuoYDingXYLuRYDepression and anxiety are associated with reduced antiepileptic drug adherence in Chinese patientsEpilepsy Behav201550919526209942

- JonesRMButlerJAThomasVAPevelerRCPrevettMAdherence to treatment in patients with epilepsy: associations with seizure control and illness beliefsSeizure200615750450816861012

- ShallcrossAJBeckerDASinghAPsychosocial factors associated with medication adherence in ethnically and socioeconomically diverse patients with epilepsyEpilepsy Behav20154624224525847430

- HovingaCAAsatoMRManjunathRAssociation of non-adherence to antiepileptic drugs and seizures, quality of life, and productivity: survey of patients with epilepsy and physiciansEpilepsy Behav200813231632218472303

- SmithsonWHHukinsDBuelowJMAllgarVDicksonJAdherence to medicines and self-management of epilepsy: a community-based studyEpilepsy Behav201326110911323246201

- AndradeSEKahlerKHFrechFChanKAMethods for evaluation of medication adherence and persistence using automated databasesPharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf200615856557416514590

- NakhutinaLGonzalezJSMargolisSASpadaAGrantAAdherence to antiepileptic drugs and beliefs about medication among predominantly ethnic minority patients with epilepsyEpilepsy Behav201122358458621907627

- BautistaREGrahamCMukardamwalaSHealth disparities in medication adherence between African-Americans and Caucasians with epilepsyEpilepsy Behav201122349549821907630

- BautistaREGonzalesWJainDFactors associated with poor seizure control and increased side effects after switching to generic antiepileptic drugsEpilepsy Res2011951–215816721530177

- PaschalAMRushSESadlerTFactors associated with medication adherence in patients with epilepsy and recommendations for improvementEpilepsy Behav20143134635024257314

- MoluguluNGubbiyappaKSVasudeva MurthyCRLumaeLMruthyunjayaATEvaluation of self-reported medication adherence and its associated factors among epilepsy patients in Hospital Kuala LumpurJ Basic Clin Pharm20167410527999469

- ZeberJECopelandLAPughMJVariation in antiepileptic drug adherence among older patients with new-onset epilepsyAnn Pharmacother201044121896190421045168

- SweilehWMIhbeshehMSJararISSelf-reported medication adherence and treatment satisfaction in patients with epilepsyEpilepsy Behav201121330130521576040

- ChesaniukMChoiHWicksPStadlerGPerceived stigma and adherence in epilepsy: evidence for a link and mediating processesEpilepsy Behav20144122723125461221

- TivMVielJFMaunyFMedication adherence in type 2 diabetes: the ENTRED study 2007, a French Population-Based StudyPLoS One201273e3241222403654

- SchachterSCBotanicals and herbs: a traditional approach to treating epilepsyNeurotherapeutics20096241542019332338

- DanesiMAAdetunjiJBUse of alternative medicine by patients with epilepsy: a survey of 265 epileptic patients in a developing countryEpilepsia19943523443518156955

- MurthyJMSome problems and pitfalls in developing countriesEpilepsia200344Suppl 1(s1)3842

- RadhakrishnanKPandianJDSanthoshkumarTPrevalence, knowledge, attitude, and practice of epilepsy in Kerala, South IndiaEpilepsia20004181027103510961631

- IslahudinFTanSMedication knowledge and adherence in nephrology patientsInt J Pharm Bio Sci201331459466

- OmarMSSanKLDiabetes knowledge and medication adherence among geriatric patient with type 2 diabetes mellitusInt J Pharm Pharm Sci201463103106

- VervloetMLinnAJvan WeertJCde BakkerDHBouvyMLvan DijkLThe effectiveness of interventions using electronic reminders to improve adherence to chronic medication: a systematic review of the literatureJ Am Med Inform Assoc201219569670422534082

- GrenardJLMunjasBAAdamsJLDepression and medication adherence in the treatment of chronic diseases in the United States: a meta-analysisJ Gen Intern Med201126101175118221533823

- KoenigHGGeorgeLKTitusPReligionTPReligion, spirituality, and health in medically ill hospitalized older patientsJ Am Geriatr Soc200452455456215066070

- HatahELimKPAliAMMohamed ShahNIslahudinFThe influence of cultural and religious orientations on social support and its potential impact on medication adherencePatient Prefer Adherence2015958925960641

- StaniszewskaASmoleńskaEReligioniUHealth Behaviors Related to the Use of Drugs among Patients with EpilepsyAm J Health Behav201741451151728601110

- SzaboCAComplementary/alternative medicine for epilepsyNeurology2003614E7E812939458