Abstract

Purpose

This study summarizes findings from objective assessments of compliance (or adherence) and persistence with ocular hypotensive agents in patients with glaucoma and ocular hypertension.

Design

Systematic literature review.

Methods

A PubMed and reference list search was conducted across publication years 1970–2010, using these terms and variants: “compliance,” the equivalent term “adherence,” and “persistence” in patients with these conditions and therapies. Summaries of selected studies were stratified by measurement method (electronic monitor, prescription fills review, medical chart review). Measures of central tendency across studies were calculated for commonly-reported compliance or persistence measures.

Results

Fifty-eight articles met all inclusion/exclusion criteria: measurement of compliance–electronic monitoring (seven studies reported in 14 articles), measurement of compliance/ persistence–prescription records (36 studies in 38 articles), and measurement of persistence– medical chart review (six studies in six articles). From electronic monitoring, most therapy-experienced patients took medication consistently, but ≥20% met criteria for poor compliance. From prescription records, only 56% (range 37%–92%) of the days in the first therapy year could be dosed with the medication supply dispensed over this period. At 12 months from therapy start, only 31% (range 10%–68%) of new therapy users had not discontinued, and 40% (range 14%–67%) had not discontinued or changed the initial therapy. From medical chart review, only 67% (range 62%–78%) of patients remained persistent 12 months after starting therapy.

Conclusions

Evidence provided by this review suggests that poor compliance and persistence has been and remains a common problem for many glaucoma patients, and is especially problematic for patients new to therapy. The direction of empirical research should shift toward a greater emphasis on understanding of root causes and identification and testing of solutions for this problem.

Introduction

As with many chronic insidious conditions, such as hypertension and diabetes, unsuccessfully controlled glaucoma typically worsens through a gradual progression, producing few symptoms until further permanent debilitation occurs, the latter condition being diagnosed in part upon the appearance of damage to the optic nerve (eg, cupping or loss of visual field). Glaucoma may be preceded by the appearance of ocular hypotension, an asymptomatic condition marked by elevated intraocular pressure (IOP) which often, but not necessarily, progresses to glaucoma.

Without the reinforcing amelioration of symptoms through use of pharmacotherapy, patients with glaucoma and ocular hypertension may be less inclined to maintain regular and continued use of their ocular hypotensive therapy. The additional self-administration hurdle of topical eye drops (compared with the oral formulations commonly used in other conditions) may further depress the motivation of these patients to comply and persist with therapy.Citation1

In a recent editorial, Quigley makes a case for why clinicians should seriously consider this problem:Citation2

“If we could help patients with glaucoma take their drops better, it would be like doubling the effect of their treatment – the equivalent of adding a second drop. This is true because, on average, patients with chronic medical conditions take from 30% to 70% of prescribed medication doses, and up to half discontinue medications in the first months of therapy.Citation3,Citation4 These dismal facts apply to the use of eye medicines as well.”Citation5

Although one reviewCitation6 found no strong evidence supporting an association between compliance and glaucoma progression, longitudinal research into this association remains quite limited. For ophthalmologists, the treatment goal remains: to provide patients with appropriate ocular hypotensives for their clinical and personal needs and to encourage compliance so that a desired level of IOP is reached.

Although one might consider compliance and persistence problems in glaucoma to be common knowledge, systematic reviews are useful for providing a more objective and thorough summary of the weight of evidence across the empirical knowledge base. In a 2005 systematic review devoted to glaucoma non-compliance, Olthoff et al reported that the proportion of patients who deviated from their prescribed medication regimen ranged from 5% to 80%.Citation6 These authors further found that no determinants (patient factors) were sufficiently sensitive and specific to accurately identify potential non-compliers. In a recent systematic review of glaucoma therapy issues, which also included a section on compliance and persistence problems, Lu et al found that “[r]ates of nonadherence ranged between 23% and 60% over 12 months … [r]ates of non-persistence ranged between 30% and 95% at 1 year.”Citation7

Since the time of the focused review by Olthoff et al,Citation6 the number of empirical publications on this topic has approximately doubled (based on the number of eligible studies identified in the current study). The purpose of the current study is to update these earlier reviewsCitation6,Citation7 on the measured magnitude of compliance or persistence problems in glaucoma (but this time limiting the scope to objective assessments rather than addressing the problematic issues related to self-reported compliance assessment without objective reference), to stratify findings by measurement method used (ie, electronic monitor, prescription fills, and medical chart), since each captures a different aspect of compliance and persistence, and to summarize findings by central tendency rather than by all-encompassing, but perhaps less-useful general ranges of findings. Due to the large number of eligible studies identified in the current review, additional issues examined in earlier reviews regarding the association between choice of agent and associated levels of compliance or persistence,Citation7 and the association of compliance and persistence with visual field lossCitation6 are not examined, but are left for future focused evaluations.

Methods

Terminology

In a recent report, a health outcomes working group cited the lack of guidance regarding the terms “compliance,” “adherence,” and “persistence.”Citation8 This group concluded that compliance and adherence are synonyms, compliance simply being the more commonly used term. Medication compliance (or its synonym adherence) is thus defined as “…the degree or extent of conformity to the recommendations about day-to-day treatment by the provider with respect to the timing, dosage, and frequency.”Citation8 Medication persistence was further defined by this working group as “… the act of continuing the treatment for the prescribed duration. It may be defined as ‘the duration of time from initiation to discontinuation of therapy’.”Citation8 Despite the finding of this working group for equivalence of the terms “compliance” and “adherence,” Osterberg and Blaschke state, that “[t]he word ‘adherence’ is preferred by many health care providers, because ‘compliance’ suggests that the patient is passively following the doctor’s orders and that the treatment plan is not based on a therapeutic alliance or contract established between the patient and the physician.”Citation9 However, for purpose of this review, we avoid interpretation of authors’ intent in usage of these terms (which is often unclear) but rather favor the position of this working group to view the term “adherence” as neither less derogatory nor as more preferred by patients, but as simply synonymous with “compliance.”Citation8 Thus, to provide a standardized terminology, in the body of this review we substitute the term “compliance” for those instances where authors used the term “adherence.” However, to maintain a bridge of continuity with the original publication, in the summary tables describing each study we provide the exact terms as used by the original authors.

Literature search and article selection

A systematic literature review was conducted using the PubMed search tool to search MEDLINE and other life science journals (www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed). The following search terms, applied to the full PubMed database, were used: (compliance OR adherence OR adherent OR persistence OR persistency) AND (glaucoma OR ocular hypertension). English language studies published in journals over the time period 1/1/1970–12/31/2010 were included (search last updated 2/1/2011). Reference sections within articles that met inclusion and exclusion criteria, as well as any published literature reviews, were also considered to identify additional titles.

One reviewer (GR) independently screened titles. Abstracts of potential topic-related studies were then reviewed. When an abstract was not available or did not provide enough detail for determining inclusion, full text articles were retrieved. Studies that were eligible for inclusion for the current review included only those that reported original research findings for at least one objective assessment of compliance or persistence for patients receiving any ocular hypotensive agent. Any study that reported patient or physician self-assessed (subjective) measures of compliance or persistence was examined, but was not included in the current review unless one or more objective measures was also obtained and reported within the same study.

The following types of studies were excluded from this review: (1) editorials, letters, and other commentary pieces, (2) narrative or clinical topic reviews, (3) case studies, (4) studies that had required failure on previous glaucoma therapy as an inclusion criterion for subject selection (thus containing an uncontrolled bias of regression to the mean), (5) interventional studies (such studies would typically not reflect usual care for glaucoma), unless a separate pre-interventional observation period was conducted for the entire patient sample (both study arms). Studies that selected patients who were not new to ocular hypotensive therapy or who were required to meet some minimum threshold of persistence on therapy were not excluded from this review. However, such selection rules could have affected findings and are thus separately identified by study when employed.

Data abstraction

The full text of included articles was reviewed. One reviewer (GR) reviewed each study and extracted information for placement in a summary table organized by objective estimation method, citation, design summary, endpoint(s) measured, patient selection/study setting, study year, and summarized study findings on these endpoints.

Persistence and compliance findings across drug cohorts

Several studies quantified persistence on therapy by using survival analysis methods. The primary focus of such studies was a comparison of the relative risk of time to therapy failure among products or classes of ocular hypotensive agents. Therapy failure was typically defined as discontinuation or change of therapy or both. Few such survival studies reported the proportion of patients who had failed therapy by combining all cohorts. Even among individual cohorts, few reported exact proportions of patients who had failed therapy at specific points in time (eg, at 180 days, 1-year, 2-year intervals) unless such findings were displayed as Kaplan–Meier (KM) or Cox Proportional Hazard Model plots.

We developed a method to summarize findings for the entire study sample when results were reported only by drug cohort or as KM or Cox survivor function plots. The proportion remaining persistent at 12 months from treatment start was recorded for each such study (no study had a shorter follow-up). For those whose 12-month persistence findings were available only within plots rather than in table or text, the following method was used: for each article that was not already available as an electronic file, we scanned plots from the printed copy. For all plots, SnagIt 8.0 (www.techsmith. com) was used to convert a full-screen magnification of the displayed electronic graph to a high-quality JPEG graphic file. Engage Digitizer 4.1 (www.digitizer.sourceforge.net), an open-source software package designed for plot-to-data conversions, was used to translate the JPEG plot line for each cohort to a spreadsheet of persistence values, at the points where the y-axis (percentage remaining persistent) intersected the corresponding time value immediately before, through and after 12 months, as shown at the x-axis. For the 12-month time point, the mean persistence (n-weighted by drug cohort), and range of persistence values across all drug cohorts within each study were calculated and reported.

Many of the authors described the same study sample in two or more published articles. However, in each of these articles, a different analysis of that sample data was reported. For efficiency in this review, findings from multiple articles appearing to use the same cohort have been combined within tables into a single group of summarized findings (ie, as a single “study group”). However two studiesCitation10,Citation11 that analyzed a subsample from within a larger sample are considered for this review as new studies, and are separately described. Stata (Intercooled 8.0, College Station, TX) was used for statistical analysis.

Unless otherwise indicated, all measures of compliance or persistence refer to usage of the originally prescribed agent only. However, in two studies noted below, by Gurwitz et al,Citation12,Citation13 usage of any ocular hypotensive following the initially prescribed agent was included within the compliance estimate.

Results

The last updated search of the PubMed database (2/11/2011) yielded 635 unique titles. This literature search and review of reference sections yielded 58 articles (comprising 49 study groups) that were deemed to have met all inclusion and exclusion criteria. These articles were categorized by measurement method and are separately listed by study group in , , and .

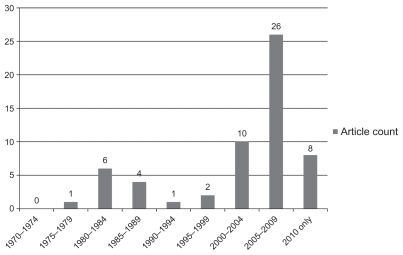

summarizes the count of reviewed articles by publication year. Few articles were published before the year 2000. Thirty-four of the 58 articles were published between 2005 and 2010.

Measurement of compliance – electronic monitoring

Electronic monitoring provides a means of monitoring compliance by objectively capturing the opening and closing of a vial enclosure, or the vial itself, by study subjects over a defined follow-up period. Both the date and time for each instance of opening and closing are captured. The design of these studies is prospective; all subjects have agreed to participate. Depending on the design of the study, subjects may, or may not, have been told that usage of medication was being monitored. Because of the precise level of detail on timely usage of medication over time, this method has been referred to as the “gold standard” for compliance measurement.Citation14,Citation15 Limitations with electronic monitoring include the short follow-up period generally available, and the potential for introducing experimenter’s bias, both a consequence of the clinical trial-like setting of such studies. lists the seven identified non-interventional study groups (reported in 14 articles) using electronic monitors.

Norrell, in 1979, published the earliest of all articles evaluated in this review, evaluating usage within a group of patients of a small box-like monitoring device that held a pilocarpine vial.Citation16 This was followed by six articlesCitation17–Citation22 reporting separate analyses of the same Swedish cohort and a separate study that analyzed a sub-sample of this larger cohort, by Granstrom (in 1985).Citation10 Kass et al (in 1986),Citation23,Citation24 and Kass et al (in 1987)Citation25 separately reported findings from two US cohorts using a smaller, integrated vial/monitoring device. Robin et al (in 2007),Citation26 Hermann et al (in 2010),Citation27 and Hermann et al (in 2010)Citation28 reported findings from separate cohorts in the US, Greece, and France, respectively, each of which also used an integrated vial/monitoring device. All studies appeared to examine patients who were existing users of ocular hypotensive therapy, and all, except Robin et al,Citation26 masked the purpose of the monitor from some or all subjects; in Hermann et alCitation27 patients were randomly assigned to masked and unmasked cohorts. The latter study found no significant differences in among compliance endpoints between masked and unmasked cohorts.

Among all monitoring studies, the lowest rates of compliance were found in the recent Hermann et al studies;Citation27,Citation28 each evaluated brimonidine users. Over a 1-month period the ratios of recorded-to-intended doses across patient samples in the two countries examined were 62%Citation28–64%Citation27 for thrice-daily users vs 72%Citation28–73%Citation27 for twice-daily users. Kass et al reported that, over a 1-month period, only 76% of prescribed doses were taken in a study of pilocarpine usersCitation24 vs 83% in a later study of timolol users.Citation25 Norell and Granstrom found, over a 20-day period, that 90% of prescribed doses of pilocarpine appeared to be administered (only 10% were missed).Citation18 Robin et al found, over a 60-day period, that 97% of prescribed doses of prostaglandins were administered within 2 hours of the scheduled time.Citation26 Despite the relatively high compliance rates found in the latter two studies, both found a substantial clustering of poor compliance behavior among certain subjects. The Norell study group found that 20% of subjects had intermediate (missed 10%–19% of doses) and 20% had poor compliance (missed ≥ 20% of doses),Citation22 while Robin et al found that 20% of subjects had poor compliance (> five errors over 20 days).Citation26

Measurement of compliance and persistence – prescription records review

The 36 study groups (reported in 38 articles) analyzing prescription fill records accounted for nearly two-thirds of all published articles in this review (). Many of these studies reported findings for both compliance and persistence endpoints. Many compared the relative persistence performance between various drug cohorts. Across these studies, summarizes findings for compliance and persistence among those specific endpoints used in more than one study.

Table 1 Mean of compliance and persistence endpoints

Time to therapy failure using survival analysis

All studies using survival analysis were conducted retrospectively with prescription fill or medical chart data. Since survival analysis employs censoring of subjects who are lost to, eg, follow- up through health plan or other database disenrollment, or reaching the end of the study, this method offers the advantage of including subjects without the need for a minimum available follow-up period. This method tracks for the occurrence of a “failure” event, eg, discontinuation, or discontinuation/ change on therapy. This method is much less precise than electronic monitoring for identifying a sentinel deviation from scheduled therapy, and must rely on establishing criteria for defining a substantial delay or gap in refilling or re-issuing of a prescription, or the introduction of a new agent, to identify a failure event. Except in two studies described below,Citation29,Citation30 this method does not typically measure whether patients return to therapy once a failure event is indentified.

As shown in , 14 studiesCitation1,Citation5,Citation30–Citation41 used survival analysis to evaluate time to therapy discontinuation from prescription fills, all but oneCitation33 of which reported findings for patients who were stated to have evidence of being new to any ocular hypotensive therapy (ie, were assumed treatment-naïve). Across the 14 studies, a mean of 31% (range 10%–68%) of all patients had remained persistent (no discontinuation) on their initial ocular hypotensive at the end of 12 months from the start of therapy. Twelve studies used survival analysis to evaluate time to therapy discontinuation or change (eg, switch of initial agent or addition of adjunctive agent).Citation32,Citation36–Citation38,Citation40–Citation47 Of these, all but threeCitation42,Citation43,Citation46 provided evidence that patients were treatment-naïve. Across the twelve studies, a mean of 40% (range 14%–67%) of patients remained persistent (no discontinuation or change) at 1 year. When analysis was restricted to those six studies separately reporting both discontinuation and discontinuation/change persistence rates,Citation32,Citation36–Citation38,Citation40,Citation41 a mean of 35% (range 19%–68%) had not discontinued and 26% (range 14%–55%) had not discontinued or changed the initially prescribed agent.

Schwartz et alCitation29 and Zimmerman et alCitation30 evaluated the subsequent disposition of patients who had discontinued therapy during the first observation year. Although only 10% of treatment-naïve patients in Zimmerman et alCitation30 were persistent on therapy at year’s end, 55% of the total sample had been non-persistent but later restarted therapy before the end of this year. Only 19% of the total sample had completely discontinued all ocular hypotensive therapy without evidence of restarting any therapy at the end of this year. Schwartz et al found that, of the subset of 65% of patients who discontinued therapy at day 180, only 51% of these treatment-naïve patients had failed to restart therapy by the end of the observation year.Citation29

Medication possession at 12 months for new therapy starts

Medication possession uses prescription fill records to assess whether a patient has a sufficient supply of the study drug on hand (ie, “possession”) at a given point in time, for instance at 6 months or 1 year after starting therapy. Although medication possession offers a simple method for estimating persistence, it does not provide a summary estimate of usage of the study drug for the period prior to the time point at which possession is assessed. For the three studiesCitation5,Citation48,Citation49 that reported medication possession at 12 months (), a mean of 51% (range 44%–59%) of all patients had a supply of the initially prescribed agent on hand at year’s end. Separately, Wilensky et alCitation50 found, for patients who had successfully remained on therapy for at least 3 months, that 69% later had possession at 1 year. Each of the medication possession studies evaluated only patients who were new to therapy.

Proportion of days covered (PDC) and medication possession ratio (MPR)

The PDC and MPR both capture approximate days over a given period for which patients have sufficient days supply to administer therapy. Both the MPR and PDC use the same numerator, the sum of days supply of all prescription fills over the period. However, while the MPR uses the number of elapsed days from the initial fill to the final fill of a prescription over the follow-up period, the PDC uses elapsed days from initial fill until a given point in time (eg, 6 months, 12 months) after the initial fill as the denominator. For the six studies that reported MPR or PDC rates during the 12 months after therapy start (five of which evaluated treatment-naïve patients),Citation1,Citation12,Citation13,Citation31,Citation49,Citation51 56% (range 37%–92%) of the days in the first therapy year could be dosed with the total days supply of prescriptions dispensed over this period. Separately, Friedman et al found, for treatment-naïve patients, a mean MPR of 64% across a mean follow-up of 22 months.Citation48 Wilensky et al found a PDC of 76% for patients over the first year who were treatment-naïve but who had been continuously persistent on therapy for 90 days following therapy start.Citation50 Djafari et al found that 72% of patients had a PDC ratio of ≥75% over a 2-year period, for a mix of patients new and not new to therapy.Citation52

Other measures using prescription fills

Lee et al found that 89%, 71%, and 22% of patients (likely existing users) had at least one significant gap in therapy during a 12-month follow-up period when evaluating allowed gaps of 45, 60, and 120 days, respectively.Citation53 Friedman et al found that 90% of treatment-naïve users experienced at least one significant gap over an average 22-month follow-up period; further, 20% of all patients discontinued all ocular hypotensives, with no evidence of adding, switching, or restarting agents.Citation48 Another study by Friedman et al reported associations of MPR with patient-reported factors in a subset of patients from this earlier study but did not report MPR estimates.Citation54 Higginbotham et al reported that only 30% of existing or new therapy users had not changed or discontinued any ocular hypotensive agent during the 1-year period after audit of a retail pharmacy database.Citation55 Gurwitz et al also reported that a mean of 24% of patients failed to receive a refill or fill for any ocular hypotensive agent (original or new) in the year following start of therapy in treatment-naïve patients ().Citation12,Citation13 Muir et al reported that patients enrolled in a study of factors related to compliance had only refilled their ocular hypotensive a mean of 2.5 times during the 6 months prior to being interviewed.Citation56,Citation57 Robin et al found in a study of patients who were persistent with latanoprost in the year prior to receiving at least two fills of an adjunctive agent that the mean interval between refills for latanoprost increased from 40 days prior to introduction of the adjunctive agent to 47 days afterwards.Citation14 Rotchford and Murphy reported that 51% of patients (existing users) for whom dispensing information was available did not have sufficient timolol to medicate as prescribed over the observed treatment year.Citation58 Using a combination of prescription records and patient self-reports of non-adherence to define refill non-adherence, Stryker et al found that 67% of existing therapy users were classified as non-adherent over a non-defined observation period. Citation59 Yousuf and Jones found that, even within an inpatient hospital setting, mean adherence rates with prescribed ocular hypotensive medication was only 67%.Citation60

Measurement of compliance and persistence – medical chart review

As shown in , six studiesCitation11,Citation61–Citation65 analyzed medical chart data to estimate rates of persistence among patients receiving ocular hypotensives. All but oneCitation65 analyzed persistence on therapy using survival analysis (four in treatment-naïve patients), evaluating either time to therapy change, or time to therapy discontinuation or change. Since we considered it unlikely that ophthalmologists would have discontinued therapy without replacement with some other ocular hypotensive agent, results for the five studies using either of these two persistence endpoints are combined in . Across these five studies, a mean of 67% (range 62%–78%) of patients were shown by chart to have remained persistent with their starting therapy at the end of the first therapy year. Persistence rates in the sixth studyCitation65 could not be evaluated.

Discussion

As described, the number of studies employing objective assessments of compliance and persistence in glaucoma pharmacotherapy is substantial and has recently accelerated, more than doubling over the past 6 years. Interpretation of findings across these many studies is made somewhat difficult by the heterogeneity of methods for measuring compliance and persistence endpoints, and in the varied patient selection criteria used in the studies reviewed. These multiple methods, when viewed in total, yield a range of perspectives for understanding compliance and persistence problems. However each must be interpreted with an understanding of its inherent limitations.

Although the electronic monitor likely comes closest to modeling actual medication use of the established ocular hypotensive user, such studies to date have yielded little understanding regarding users who are new to therapy. The short follow-up periods and clinical-trial-like designs somewhat limit attempts to generalize such findings to long-term use in naturalistic settings. The lack of uniformity across studies in the specific endpoints used to estimate compliance from monitoring data (as shown in ) perhaps more strongly limits attempts to compare findings across these studies.

While a review of prescription fill records offers the potential to greatly extend the observation period, describe actual drug use in natural settings, and employ standardized compliance and persistence measures, many methodological questions are left unanswered. For instance, does the days supply reported on the prescription fill record reflect the actual coverage required given what is not revealed: the patient’s ability to avoid wastage, whether a patient treats one or both eyes, the actual number of drops available in a given vial, and the effect of drug samples on these estimates?

The medical chart comes closest to what is available to the ophthalmologist as a practical tool for monitoring and perhaps correcting persistence problems with therapy, but this too has limitations. Although the prescribing physician should be aware of changes to therapy since he/she likely authorizes them, little is revealed from the chart whether a patient is compliant and persistent on a prescribed ocular hypotensive unless the patient so informs the physician or fails to request timely refills. Further, once a patient is lost to medical follow-up for failing to reschedule visits, all remaining persistence data for that patient become lost as well.

Many methodological issues found in this review appear to be independent of measurement method. For instance, many studies selected only patients who were treatment-naïve. Others evaluated existing ocular hypotensive users or a mix of the two groups. This is an important consideration for interpretation of findings, particularly since differences in compliance and persistence could be expected across these selected groups. Patients who are existing therapy users are by definition more experienced and are largely therapy survivors, having refilled at least one prescription. These users would be expected to be more likely to properly consume their initial therapy when compared those just starting therapy.

Despite design limitations among methods, much has been learned from the body of empirical research evaluated in this review. By comparing every scheduled to actual administered dose, the electronic monitor studies provide uniquely precise estimates of daily medication-taking behavior by established ocular hypotensive users. Thus, of the most commonly used glaucoma agents today, the prostaglandins and beta blockers, findings from the electronic monitor studies suggest that compliance behavior remains a problem for a substantial proportion in existing users, perhaps one in fiveCitation26 to one in four.Citation25 These studies also suggest a general trend toward greater compliance with fewer required doses per day, clearly established in Hermann et al,Citation27,Citation28 and suggested with the improved compliance observed in the timolol and prostaglandin studies compared with the thrice-daily regimens of brimonidine and pilocarpine.

The greatest strength of survival analysis-based persistence studies from prescription records is the sheer volume of evidence that most patients (perhaps two in every three) who are new to ocular hypotensive therapy will have a substantial gap in refilling their initially prescribed agent in the first year of therapy. Analysis of persistence data from medical charts suggests that perhaps one of every three patients would have undergone a change in agents, either as a switch or addition of an adjunctive agent. Accounting for this difference would yield a net count of one in three patients who had started therapy but had discontinued (without change in agents) by the end of the first therapy year. What became of therapy for these patients? Zimmerman et alCitation30 and Schwartz et alCitation29 suggest that approximately half of these would have resumed their originally prescribed therapy after this significant therapy failure or gap. A limitation of survival studies is that little is known about continued persistence on therapy for those patients who are either switched to a new agent or who return to their initial agent after a substantial gap.

Like the survival analysis, medication possession assesses persistence on therapy at a given point in time (though it lacks consideration of patients who are lost to follow-up). For new ocular hypotensive users, only half will have an apparent supply of the initially prescribed agent on hand at the end of the first therapy year. This improves considerably for “therapy survivors” who achieve initial persistence through first 90 days (two-thirds of these have possession at year’s end). Further, many patients, perhaps one in four, appear to simply fail to refill for any ocular hypotensive agent even once after starting therapy.

Although both PDC and MPR are unable to measure deviations from scheduled doses, they do offer a simple and approximate measure of days of therapy coverage or drug availability in a naturalistic setting. The low combined PDC/ MPR value of 56% for the five studies that reported year-end values appears equally poor compared with the MPR of 64% reported in the recent large-scale study of Friedman et al across an average follow-up of 22 months.Citation48 These findings further suggest that a failure to refill or sporadic refilling of ocular hypotensives is common among patients.

Unlike evidence from electronic monitoring studies of compliance, persistence with ocular hypotensive therapy does not appear to be improving with the increased availability of once-daily dosing regimens. In Friedman et al’s analysis of claims data over the period 1999–2005, a time when once-daily prostaglandins or beta blockers were available and heavily prescribed, few patients over the 22-month follow-up did not have at least one substantial gap in refilling; 20% discontinued filling of ocular hypotensives altogether.Citation48

Summary and recommendations

Despite the greater attention devoted to this issue in recent years, empirical evidence provided in this review suggests that poor compliance remains common for many glaucoma patients who are existing ocular hypotensive users. Both compliance and persistence remain problems for those who are new to such therapy.

For those new to therapy, active engagement with the patient by the ophthalmologist, physician assistant, nurse, or pharmacist is especially important in the first treatment year. Assessment should include discussion of compliance and persistence behavior, and eliciting of patient-perceived problems such as tolerability, forgetting doses, or the taking of drug holidays. Also, some evidence suggests that encouraging the patient to remain compliant with the scheduling of visits may help medication compliance. Both Gurwitz et alCitation13 and Jayawant et alCitation33 found that patients who had a higher count of ophthalmologist visits in the first year also had higher rates of ocular hypotensive compliance and persistence, respectively. Quigley et al found that missing an ophthalmology visit was associated with lower compliance with therapy.Citation66

For existing therapy users, who are more experienced, often using adjunctive therapy to control their glaucoma, important considerations, besides missing scheduled doses, are dyscompliance concerns (wrong or unsuccessful use of eyedrops).Citation27 In one study 44% of patients reported regularly missing the eye when applying drops.Citation67 Another study found that less than one-third of observed instillations in existing users were performed successfully, with 17%–25% of patients unable to place a drop in their eye.Citation68 Several of the electronic monitoring studies in this review found evidence pointing to dyscompliance. In Kass et al the weight of the pilocarpine vial utilized during the study was only weakly (r = 0.18) correlated with therapy compliance, which suggests that greater drug consumption may not be a good predictor of appropriate drug use.Citation24 Hermann et al found that some patients required up to 3.7 drops per scheduled dose per eye, implying the emptying of a full vial in as little as a week.Citation28 Robin et al found, in subjects using beta-blockers as adjunctive therapy, that 25% of the intervals between beta blocker doses were 10 hours or lower (suggesting a potential safety issue).Citation26

Gray et al, in their recent Cochrane review, examined randomized interventions to improve adherence to ocular hypotensive therapy.Citation69 Only eight eligible randomized intervention studies published until the review year 2009 were deemed as evaluable.Citation69 These authors concluded that simplified dosing regimens, reminder devices, education, and individualized care planning showed improvements in adherence rates. Adequately controlled and designed interventions that may be especially worthwhile to pursue would include: structured but interactive patient educational programs, strategies to improve physician communication, and the integration of drug with compliance device. Ocular hypotensive agents may have the highest potential for effectiveness and lowest levels of adverse effects, when delivered with dosing aids and adherence devices (see KahookCitation70).

Although more empirical studies to identify the scope of compliance and persistence problems might help track whether progress is being made, there is little need for further objective assessment in the near-term to confirm that such problems continue to exist. Building upon a legacy of more than 40 years of subjective and objective assessments, the direction of empirical compliance and persistence research in glaucoma should rapidly shift toward solutions: (1) performing rigorous and quantifiable assessments of likely root causes of non-compliance and non-persistence, to identify areas for intervention, (2) developing validated, physician-usable risk-assessment tools to monitor and predict non-compliance, (3) evaluating promising compliance-improvement interventions with strong study designs to compensate for the limited randomized-trial research to date, and (4) further expanding the eight clinical recommendations proposed by Olthoff et alCitation6 into a formalized set of guidelines for the recognition and treatment of patients who are potentially non-compliant or non-persistent.

Acknowledgments/Disclosures

The study was supported by Pfizer Inc, New York, NY, USA. GR is an employee of Informagenics, LLC who were paid consultants to Pfizer, and GFS was a paid consultant to Pfizer, both in connection with the design and conduct of the study, and development of the manuscript. SK is an employee of Pfizer Inc. GR and SK acquired, analyzed, and interpreted the data. All authors were involved in drafting the manuscript and/or revising it critically. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Supplementary materials

Table S1 Measurement of compliance – electronic monitoring studies

Table S2 Measurement of compliance and persistence – prescription fill record studies

Table S3 Measurement of persistence – medical chart review studies

References

- YeawJBennerJSWaltJGSianSSmithDBComparing adherence and persistence across 6 chronic medication classesJ Manag Care Pharm200915972874019954264

- QuigleyHAImproving eye drop treatment for glaucoma through better adherenceOptom Vis Sci200885637437518521018

- HaynesRBMcDonaldHPGargAXHelping patients follow prescribed treatment: clinical applicationsJAMA2002288222880288312472330

- DiMatteoMRGiordaniPJLepperHSCroghanTWPatient adherence and medical treatment outcomes: a meta-analysisMed Care200240979481112218770

- NordstromBLFriedmanDSMozaffariEQuigleyHAWalkerAMPersistence and adherence with topical glaucoma therapyAm J Ophthalmol2005140459860616226511

- OlthoffCMSchoutenJSvan de BorneBWWebersCANoncompliance with ocular hypotensive treatment in patients with glaucoma or ocular hypertension an evidence-based reviewOphthalmology2005112695396115885795

- LuVHGoldbergILuCYUse of glaucoma medications: state of the science and directions for observational researchAm J Ophthalmol20101504569574e56920678750

- CramerJARoyABurrellAMedication compliance and persistence: terminology and definitionsValue Health2008111444718237359

- OsterbergLBlaschkeTAdherence to medicationN Engl J Med2005353548749716079372

- GranstromPAProgression of visual field defects in glaucoma. Relation to compliance with pilocarpine therapyArch Ophthalmol198510345295313985832

- HahnSRKotakSTanJKimEPhysicians’ treatment decisions, patient persistence, and interruptions in the continuous use of prostaglandin therapy in glaucomaCurr Med Res Opin201026495796320163296

- GurwitzJHGlynnRJMonaneMTreatment for glaucoma: adherence by the elderlyAm J Public Health19938357117168484454

- GurwitzJHYeomansSMGlynnRJLewisBELevinRAvornJPatient noncompliance in the managed care setting. The case of medical therapy for glaucomaMed Care19983633573699520960

- RobinALCovertDDoes adjunctive glaucoma therapy affect adherence to the initial primary therapy?Ophthalmology2005112586386815878067

- ClaxtonAJCramerJPierceCA systematic review of the associations between dose regimens and medication complianceClin Ther20012381296131011558866

- NorellSEImproving medication compliance: a randomised clinical trialBr Med J19792619710311033519269

- NorellSMedication behaviour. A study of outpatients treated with pilocarpine eye drops for primary open-angle glaucomaActa Ophthalmol Suppl19801431286257026

- NorellSEGranstromPASelf-medication with pilocarpine among outpatients in a glaucoma clinicBr J Ophthalmol19806421371417362816

- NorellSEMonitoring compliance with pilocarpine therapyAm J Ophthalmol19819257277317304700

- NorellSEAccuracy of patient interviews and estimates by clinical staff in determining medication complianceSoc Sci Med E198115157617271967

- GranstromPAGlaucoma patients not compliant with their drug therapy: clinical and behavioural aspectsBr J Ophthalmol19826674644707093186

- GranstromPANorellSVisual ability and drug regimen: relation to compliance with glaucoma therapyActa Ophthalmol (Copenh)19836122062196880634

- KassMAMeltzerDWGordonMCooperDGoldbergJCompliance with topical pilocarpine treatmentAm J Ophthalmol198610155155233706455

- KassMAGordonMMeltzerDWCan ophthalmologists correctly identify patients defaulting from pilocarpine therapy?Am J Ophthalmol198610155245303706456

- KassMAGordonMMorleyREJrMeltzerDWGoldbergJJCompliance with topical timolol treatmentAm J Ophthalmol198710321881933812621

- RobinALNovackGDCovertDWCrockettRSMarcicTSAdherence in glaucoma: objective measurements of once-daily and adjunctive medication useAm J Ophthalmol2007144453354017686450

- HermannMMPapaconstantinouDMuetherPSGeorgopoulosGDiestelhorstMAdherence with brimonidine in patients with glaucoma aware and not aware of electronic monitoringActa Ophthalmol2011894e300e30521106046

- HermannMMBronAMCreuzot-GarcherCPDiestelhorstMMeasurement of adherence to brimonidine therapy for glaucoma using electronic monitoringJ Glaucoma2010 [Epub ahead of print]

- SchwartzGFPlattRReardonGMychaskiwMAAccounting for restart rates in evaluating persistence with ocular hypotensivesOphthalmology2007114464865217398318

- ZimmermanTJHahnSRGelbLTanHKimEEThe impact of ocular adverse effects in patients treated with topical prostaglandin analogs: changes in prescription patterns and patient persistenceJ Ocul Pharmacol Ther200925214515219284321

- BhosleMJReardonGCamachoFTAndersonRTBalkrishnanRMedication adherence and health care costs with the introduction of latanoprost therapy for glaucoma in a Medicare managed care populationAm J Geriatr Pharmacother20075210011117719512

- DasguptaSOatesVBookhartBKVaziriBSchwartzGFMozaffariEPopulation-based persistency rates for topical glaucoma medications measured with pharmacy claims dataAm J Manag Care20028Suppl 10S25526112188168

- JayawantSSBhosleMJAndersonRTBalkrishnanRDepressive symptomatology, medication persistence, and associated healthcare costs in older adults with glaucomaJ Glaucoma200716651352017873711

- OwenCGCareyIMde WildeSWhincupPHWormaldRCookDGPersistency with medical treatment for glaucoma and ocular hypertension in the United Kingdom: 1994–2005Eye (Lond)20092351098111018617908

- RaitJLAdenaMAPersistency rates for prostaglandin and other hypotensive eyedrops: population-based study using pharmacy claims dataClin Experiment Ophthalmol200735760261117894679

- ReardonGSchwartzGFMozaffariEPatient persistency with ocular prostaglandin therapy: a population-based, retrospective studyClin Ther20032541172118512809964

- ReardonGSchwartzGFMozaffariEPatient persistency with pharmacotherapy in the management of glaucomaEur J Ophthalmol200313Suppl 4S445212948052

- SchwartzGFReardonGMozaffariEPersistency with latanoprost or timolol in primary open-angle glaucoma suspectsAm J Ophthalmol2004137Suppl 1S131614697910

- ShayaFTMullinsCDWongWChoJDiscontinuation rates of topical glaucoma medications in a managed care populationAm J Manag Care20028Suppl 10S27127712188170

- SpoonerJJBullanoMFIkedaLIRates of discontinuation and change of glaucoma therapy in a managed care settingAm J Manag Care20028Suppl 10S26227012188169

- ReardonGSchwartzGFMozaffariEPatient persistency with topical ocular hypotensive therapy in a managed care populationAm J Ophthalmol2004137Suppl 1S31214697909

- De NataleRLafumaABerdeauxGCost effectiveness of travoprost versus a fixed combination of latanoprost/timolol in patients with ocular hypertension or glaucoma: analysis based on the UK general practitioner research databaseClin Drug Investig2009292111120

- DenisPLafumaABerdeauxGCosts and persistence of alpha-2 adrenergic agonists versus carbonic anhydrase inhibitors, both associated with prostaglandin analogues, for glaucoma as recorded by The United Kingdom General Practitioner Research DatabaseClin Ophthalmol20082232132919668723

- LafumaABerdeauxGCosts and effectiveness of travoprost versus a dorzolamide + timolol fixed combination in first-line treatment of glaucoma: analysis conducted on the United Kingdom General Practitioner Research DatabaseCurr Med Res Opin200723123009301617958945

- LafumaABerdeauxGCosts and persistence of carbonic anhydrase inhibitor versus alpha-2 agonists, associated with beta-blockers, in glaucoma and ocular hypertension: an analysis of the UK-GPRD databaseCurr Med Res Opin20082451519152718413015

- LafumaALaurendeauCBerdeauxGCosts and persistence of brimonidine versus brinzolamide in everyday glaucoma care: an analysis conducted on the UK General Practitioner Research DatabaseJ Med Econ200811348549719450100

- ZhouZAlthinRSforzoliniBSDhawanRPersistency and treatment failure in newly diagnosed open angle glaucoma patients in the United KingdomBr J Ophthalmol200488111391139415489479

- FriedmanDSQuigleyHAGelbLUsing pharmacy claims data to study adherence to glaucoma medications: methodology and findings of the Glaucoma Adherence and Persistency Study (GAPS)Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci200748115052505717962457

- ReardonGSchwartzGFKotakSPersistence on prostaglandin ocular hypotensive therapy: an assessment using medication possession and days covered on therapyBMC Ophthalmol201010520196848

- WilenskyJFiscellaRGCarlsonAMMorrisLSWaltJMeasurement of persistence and adherence to regimens of IOP-lowering glaucoma medications using pharmacy claims dataAm J Ophthalmol2006141Suppl 1S283316389058

- TraversoCEWaltJGSternLSDolgitserMPharmacotherapy compliance in patients with ocular hypertension or primary open-angle glaucomaJ Ocul Pharmacol Ther2009251778219232009

- DjafariFLeskMRHarasymowyczPJDesjardinsDLachaineJDeterminants of adherence to glaucoma medical therapy in a long-term patient populationJ Glaucoma200918323824319295380

- LeePPWaltJGChiangTHGuckianAKeenerJA gap analysis approach to assess patient persistence with glaucoma medicationAm J Ophthalmol2007144452052417692273

- FriedmanDSHahnSRGelbLDoctor-patient communication, health-related beliefs, and adherence in glaucoma results from the Glaucoma Adherence and Persistency StudyOphthalmology20081158132013271327.e1e318321582

- HigginbothamEJHansenJDavisEJWaltJGGuckianAGlaucoma medication persistence with a fixed combination versus multiple bottlesCurr Med Res Opin200925102543254719731993

- MuirKWSantiago-TurlaCStinnettSSHealth literacy and adherence to glaucoma therapyAm J Ophthalmol2006142222322616876500

- MuirKWSantiago-TurlaCStinnettSSGlaucoma patients’ trust in the physicianJ Ophthalmol2009200947672620339452

- RotchfordAPMurphyKMCompliance with timolol treatment in glaucomaEye (Lond)199812Pt 22342369683946

- StrykerJEBeckADPrimoSAAn exploratory study of factors influencing glaucoma treatment adherenceJ Glaucoma2010191667220075676

- YousufSJJonesLSAdherence to topical glaucoma medication during hospitalizationJ Glaucoma2010 [Epub ahead of print]

- AriasASchargelKUssaFCanutMIRoblesAYSanchezBMPatient persistence with first-line antiglaucomatous monotherapyClin Ophthalmol2010426126720463793

- DayDGSchacknowPNSharpeEDA persistency and economic analysis of latanoprost, bimatoprost, or beta-blockers in patients with open-angle glaucoma or ocular hypertensionJ Ocul Pharmacol Ther200420538339215650513

- DiestelhorstMSchaeferCPBeusterienKMPersistency and clinical outcomes associated with latanoprost and beta-blocker monotherapy: evidence from a European retrospective cohort studyEur J Ophthalmol200313Suppl 4S212912948050

- TingeyDBernardLMGrimaDTMillerBLamAIntraocular pressure control and persistence on treatment in glaucoma and ocular hypertensionCan J Ophthalmol200540216116916049529

- KashiwagiKChanges in trend of newly prescribed anti-glaucoma medications in recent nine years in a Japanese local communityOpen Ophthalmol J2010471120556196

- QuigleyHAFriedmanDSHahnSREvaluation of practice patterns for the care of open-angle glaucoma compared with claims data: the Glaucoma Adherence and Persistency StudyOphthalmology200711491599160617572498

- SleathBRobinALCovertDByrdJETudorGSvarstadBPatientreported behavior and problems in using glaucoma medicationsOphthalmology2006113343143616458967

- StoneJLRobinALNovackGDCovertDWCagleGDAn objective evaluation of eyedrop instillation in patients with glaucomaArch Ophthalmol2009127673273619506189

- GrayTAOrtonLCHensonDHarperRWatermanHInterventions for improving adherence to ocular hypotensive therapyCochrane Database Syst Rev20092CD00613219370627

- KahookMYDevelopments in dosing aids and adherence devices for glaucoma therapy: current and future perspectivesExpert Rev Med Devices20074226126617359230