Abstract

Background

When suffering from cystic fibrosis (CF), a number of problems may arise during adolescence; for example, poor adherence. The problems may be attributed to the adolescent being insufficiently prepared for adult life. Research on different ways of parenting adolescents with CF and the influence of different parenting styles on the adolescents’ adherence to treatment is still limited.

Aim

The aim of this study was to identify the types of parental support that adolescents and young adults with CF want and find helpful in terms of preparing them for adult life.

Methods

Sixteen Danish adolescents with CF, aged 14–25, participated in the study. Two focus group interviews were carried out, one for 14–18-year-olds and one for 19–25-year-olds. Individual interviews were conducted, with three subjects. Using interpretive description strategy, a secondary analysis of the interview data was conducted.

Results

The adolescents and young adults wanted their parents educated about the adolescent experience. They wanted their parents to learn a pedagogical parenting style, to learn to trust them, and to learn to gradually transfer responsibility for their medical treatment. Additionally, the adolescents noted that meeting other parents may be beneficial for the parents.

Conclusion

The findings of this study suggest that adolescents and young adults with CF want their parents to be educated about how to handle adolescents with CF and thereby sufficiently prepare them for adult life.

Introduction

Cystic fibrosis (CF) is the most common hereditary and life-shortening disease in Caucasians, affecting approximately 1 in 4700 people in the Danish population. Most patients develop chronic pulmonary disease that is characterized by airway obstruction and the formation of bronchial mucus that leads to repeated airway infections and reduced lung function over time. The majority of patients with CF also have a severe reduction of the extrinsic function of the pancreas, resulting in malabsorption and malnutrition. Treatment is time-consuming and consists of airway clearance treatments, aerosolized medications, enzymes, special diets, and antibiotics.

A number of problems arise during the transition from childhood to adulthood in terms of the treatment and care of CF. In adolescence, there is often a considerable reduction in lung function,Citation1,Citation2 as well as delayed growthCitation3 and reduction in quality of life,Citation4 especially when lung function deteriorates.Citation5 Further, adherence to treatment decreases during adolescence.Citation6,Citation7 These problems can partly be attributed to the adolescent being insufficiently prepared for adult life.Citation8

Preparing adolescents with CF for adult life can be a complex and challenging task for the parents and for the health professionals. Adolescents may have different preferences, aims, and priorities from those of their parents and the health professionals.

The present study is based on the secondary analysis of interview data from adolescents and young adults with CF collected in the context of a larger study with the overall rationale to gather information about the health care services that according to adolescents with CF and their parents can best prepare the adolescents for adult life; the intention being to improve future health care services and hopefully prevent a decrease in major disease-related physiological and quality- of-life parameters among the adolescents.

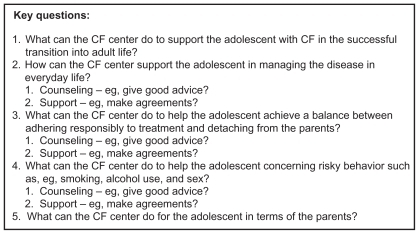

At first, the data were used to develop questionnaires for adolescents with CF with the aim of getting general knowledge of which health services can support the adolescents on their way to adult life. Accordingly, the key questions from the interview guide solicited broad opinions on the need for support from health care professionals (). However, during the first analysis of the adolescent data, the parent–adolescent relationship emerged as an ongoing and prominent theme. This emerging theme indicated that the parent–adolescent relationship is significant for these patients with respect to their preparation for adult life. CF health professionals often note that parents of CF patients worry that their adolescents value parties and being with their friends more than taking care of their health. Thus, there seemed to be a mismatch between the adolescents’ and the parents’ mutual expectations. Studies about parenting adolescents with chronic diseases have been carried out, but research about the adolescent’s own perspective on this topic is very limited, particularly in the area of CF. Therefore, the authors of this paper conducted a secondary analysis of the same interview data to identify which kind of parental support adolescents and young adults with CF highlight as beneficial in their preparation for adult life. Prior to the secondary data analysis the literature was consulted.

Parent–adolescent relationship

During the last few decades, studies of normative adolescent development have increased, and there has been a growing interest in parent–adolescent relationships. The literature suggests that relationships with parents remain the most influential of all adolescent relationships.Citation9 Accordingly, different ways of parenting have been studied. Authoritative parenting, originally described by Baumrind,Citation10 is warm and involved, but also firm and consistent in terms of establishing and enforcing guidelines, limits, and developmentally appropriate expectations.Citation11 Authoritative parenting is a beneficial parenting style in that adolescents from authoritative homes achieve more in school, report less depression, score higher on self-esteem measures, and are less likely to engage in antisocial behavior.Citation12 Taking these positive outcomes in normative adolescent development into consideration, it is surprising that there are few studies that address parental support and parenting styles for adolescents with CF.

In a review of chronic illness during adolescence, parents were found to be the best allies in helping adolescents with their disease and guiding them through treatment,Citation13 and a study of chronically ill adolescents found that support from parents, physicians, and friends seemed to predict good adherence with health regimens.Citation14 Hence, parental involvement in the adolescent’s disease management seems to be important. An American study showed that adolescents with chronic diseases who spent more of their treatment time supervised by parents, particularly mothers, had better adherence,Citation15 and likewise, a review on the role of parental involvement in diabetes management suggested that a premature withdrawal of parental involvement is associated with poor diabetes outcomes, whereas continued parental support and monitoring is associated with better outcomes among adolescents.Citation16 Furthermore, a study of adolescents with type 1 diabetes reported that a supportive and emotionally warm parenting style (authoritative parenting style) promoted improved quality of life.Citation17 However, a study on sickle-cell disorder and thalassemia found that adolescents often feel that parents are so concerned about the illness that they focus on the illness at the expense of the adolescent as an individual person.Citation18

Research in adolescents with CF has presented the same picture. A more positive family relationship was found to associate with better adherence to airway clearance treatments and aerosolized medication,Citation19 and a questionnaire survey found that family relationships including conflict have a significant impact on the young people’s psychological functioning and adjustment.Citation20 Furthermore, nonsupportive behaviors from family members, particularly parental nagging, was found to predict psychological maladjustment.Citation21

Summing up, parenting chronically ill adolescents may lead to conflict in the parent–adolescent relationship, which may lead to adherence problems and thereby to poorer outcomes. On the other hand, parents are also the adolescent’s best support for handling their chronic disease. In order to clarify CF-specific concerns, the present study aimed to determine what kind of parental support adolescents with CF want and find beneficial in terms of preparing them for adult life. To the authors’ knowledge, this is the first study within the area of CF about the adolescents’ perspectives on their parents’ parenting styles.

Material and methods

Sample

For the primary study, a purposeful sample of 16 patients with CF between the ages of 14 and 25 years were invited to participate in the study. This age group was chosen as the authors thought the young adults could contribute experience from their recently expired adolescence. Patients infected with the bacteria Burkholderia cepacia, Achromobacter, or multiresistant Pseudomonas aeruginosa were not invited to participate according to the Danish guidelines for CF infection control.

The adolescent and young adult patients are for convenience named adolescents throughout this paper. All patients were recruited from one of two Danish CF centers.

For a purposeful, maximum variation sample, an equal distribution with regards to sex, age, living at home, and disease severity measured by lung function (forced expiratory volume in 1 second) was sought (). Three of the adolescents lived with a partner, but none of them had children. These data were extracted from the Danish Cystic Fibrosis Registry.

Table 1 Characteristics of the participants

Data collection

Two focus-group interviews were conducted in November 2008: one for 14–18-year-olds and one for 19–25-year-olds and lasted on average 1 hour and 40 minutes. Focus-group interviews are a method of improving our understanding of how people feel, think, and act in relation to a subject. Participants are encouraged to discuss attitudes, without demanding that they reach consensus, and emphasizing that there are no right and wrong answers. This makes it possible for participants in the interaction to express opinions, attitudes, and to some extent, behavior, which would otherwise be left unsaid or taken for granted.

Three individual interviews were performed because the three patients were ill the day that the focus group interview was conducted; these interviews lasted on average 25 minutes. These three patients were severely ill, and it was therefore important to interview them for the purpose of maximal variation. Using multiple data sources, eg, focus-group and individual interview, is in line with interpretive description recommendations.Citation22 An interview guide was used that was based on a review of the literature and consultation with CF clinicians and clinical nursing experts (). A few introducing questions were asked before the key questions, and likewise, a few recapitulating and closing questions were asked in the end of the interviews. The moderator ensured that all the topics in the interview guide were discussed.

The first author of this study conducted the individual interviews and acted as the moderator for the focus-group interviews, with an observer present. The interviews were recorded on audiotape and transcribed verbatim. All data collection was performed prior to both the primary and the secondary analysis. The sampling and both of the analyses were conducted by the same research group.

Although the interview guide was primarily designed to obtain information about the adolescents’ preferences to the health care system, the guide also contained questions about their parents (). In addition to information on support from the health professionals, the interviews revealed substantial information about the adolescents’ views on parenting adolescents with CF.

Analysis

The secondary analysis drew on the methodological approach termed interpretive description, which is a qualitative research strategy developed by Thorne et al.Citation23 Secondary analysis involves re-analysis of data previously collected and with a new research question. Thorne suggests five different types of secondary analyses.Citation24 A combination of analytic expansion and retrospective interpretation was found to be the most feasible for the purpose of the present study. In analytic expansion the researchers conduct a secondary interpretation of their own database to answer new or extended questions, and in the retrospective interpretation they tap into an existing database in order to develop themes that emerged but were not fully analyzed in the primary study. According to Thorne, a secondary analysis is an option, because very often the primary analysis has only captured part of the full context. However, concordance between the aim of the primary and the secondary analyses is required.Citation22 The authors of this present paper found that this requirement was met in this present study. Interpretive description does not present strict guidelines but rather draws on elements from social science traditions such as phenomenology, grounded theory, and ethnography. The strategy enables the detection of themes and patterns in the subjective perceptions of the participants, and through interpretive description, transforms these into clinically relevant information.Citation22 The overall idea of the interpretive description strategy used here was to gain a better understanding of the adolescents’ preferences in terms of parental support.

Data analysis was performed by the first author, with assistance from the third author. Differences between the focus groups and the individual interviews were explored, as it could be imagined that being in groups might make the adolescents keener about criticizing their parents, but no such differences were found. Additionally, differences between interviews with the older and the younger participants were explored, but no differences were found except that some of the older ones did not experience problems anymore, but they still had a clear memory of them. As the abovementioned considerations did not seem to give rise to any problems, it was decided to analyze the two focus groups and the three individual interviews in the same analytic process, which was an iterative, inductive, and interpretive process. First, the researchers listened to the recorded interviews and read the transcripts several times to become familiar with the content of the interviews. Second, with parenting as a tentative scaffold, each transcript was broadly coded. Third, commonalities and differences in and between the participants were explored, and codes were organized into a system of themes and patterns that were faithful to the empirical data. This analytic process resulted in an interpretive description of the kind of parental support wanted by adolescents with CF.

Ethical considerations

Prior to the interviews, the participants were informed both orally and in writing about the purpose of the interview (qualitative in-depth analyses as well as development of questionnaires), and written consent was obtained from the adolescents and, when needed, their parents. The study was registered with the Danish Data Agency Board. According to Danish law, no particular ethical permission is needed to conduct a study that does not include biomedical aspects.

Results

The adolescents demonstrated a good understanding of the challenges facing their parents, and they realized the great responsibility of rearing an adolescent with CF. Despite this, the adolescents thought their parents needed recommendations about how to best guide their adolescents with CF in an appropriate and productive way.

Overall, the adolescents noted that their parents had some difficulty parenting. They indicated that their parents needed education about how to handle adolescents with CF, and they suggested specific topics that needed to be covered by such education. According to the adolescents, the parents needed to learn a pedagogical parenting style, to learn to trust the adolescents, and to learn how to gradually hand over responsibility for disease treatment. Additionally, the adolescents noted that meeting other parents may be beneficial for the parents. Most of the adolescents expected their parents to welcome such an educational intervention and to benefit from it.

The younger adolescents were the keenest to suggest education for their parents, but most of the older adolescents also supported this idea. One exception was a male (23 years) who did not want his parents to change anything about their parenting style. This adolescent reported that his parents were helpful without being dictative or controlling, and that they had gradually trusted him to take his medical treatment.

A pedagogical parenting style

The adolescents wanted to engage in a dialog with their parents about their treatment. The adolescents needed reasons and explanations about their treatments. They did not listen to their parents when they were told, without explanation, that they must perform their treatment. Many adolescents felt that their parents were rigid and only wanted things done their own way. In contrast, the adolescents wished to have more open discussions and wished that the treatment process was more cooperative. Being treated as if they were younger than they actually were made the adolescents react inappropriately, eg, denying and hiding adherence problems.

The parents’ constant focus on the disease also frustrated the adolescents. They wished their parents would forget about the disease now and then and treat them as a regular adolescent. Younger adolescents in particular often found their parents annoying because of the constant reminders regarding medical treatment. A 15-year-old boy said:

If I had got a coin every time my mother or father said, “Did you remember to take your treatment?” I would be a millionaire today.

The older adolescents demonstrated more understanding of their parents’ numerous reminders but still felt that their parents needed guidance.

Trust

The adolescents reported that parents often checked whether they had taken their medication. Some adolescents found it humiliating, and the younger ones occasionally reacted by being defiant and uncooperative. The older adolescents had often found a way to tell their parents to mind their own business, but they remembered being annoyed when they were younger.

My father wanted to control, to control things. So when I was going to take over, we had many discussions, because he would not let me, yes, he wanted to, but then he got anxious, if I could, if I was mature enough [female, 22 years].

According to the adolescents, trust is a very important component in transferring the responsibility for medical care.

Responsibility

All of the adolescents were aware that one day they would have to take on responsibility for their disease and its treatment. Therefore it was very important to them that the responsibility was handed over while they were still living at home with their parents, and they wanted their parents to learn how to do this. In particular, the adolescents suggested that their parents should involve them at an early age in making decisions about treatment and health care. This should occur via mutual information exchange and discussion. Some adolescents suggested that the CF center should guide parents in handing over responsibility and, at the same time, guide the adolescent in taking responsibility.

Tell them [the parents] that they should try for just one week and then see how it is. To ignore the disease for a week and then see if you [the adolescent] can handle it. And if you cannot, then they can interfere [male, 15 years].

According to the adolescents, parents who fail to involve their child in decisions concerning treatment and health care risk making their adolescent feel that their treatment and health care is none of their concern; this may cause them to continue to leave the responsibility for treatment with the parents.

I do not feel I take the treatment when they [the parents] constantly say blow etc. It is as if they are my masters and they take the treatment just through my body [male, 14 years]

Although the adolescents wanted their parents to transfer responsibility, they also admitted their own laziness and reluctance to take on the responsibility.

Meeting other parents and adolescents

The adolescents suggested that parents should be able to receive education about parenting adolescents at the CF center. They thought that being educated in groups with other parents would be useful and give the parents the opportunity to exchange accounts of their experiences. One adolescent (male, 23 years), however, did not feel that his parents would benefit from meeting other parents, but advanced the viewpoint that other parents might benefit from meeting them. As mentioned previously, this adolescent did not want his parents to change their parenting style.

The adolescents also suggested that parents should meet older adolescent patients with CF who could tell them about the challenges of being young with CF and advise them on how to create a productive, cooperative relationship with their adolescent.

Discussion

The aim of this study was to determine what kind of parental support adolescents with CF want and find helpful in terms of preparing them for adult life.

The study provided information about adolescents’ preferences for helpful parental support. They suggested an educational program for parents of adolescents with CF. Such a program is clearly in line with Steinberg’s recommendations. Citation25 Steinberg, who has conducted a great deal of research on normative adolescent development, suggests a systematic, multifaceted, and ongoing public health campaign to educate parents about adolescence. She claims that parents need basic information about normative developmental changes in adolescence and about the principles of effective parenting during the adolescent years; they also need some understanding of how they and their family change during the adolescent period.Citation25 Taking this into account, it seems even more important for parents of adolescents with CF to know about parenting, as the consequences of poor parenting may be crucial for the adolescents with CF.

In this present study, the adolescents suggested that a pedagogical parenting style, transferring responsibility and trust, should be topics in the parents’ educational program. While they did not question their parents’ motives, the adolescents sometimes felt scolded by them, feeling that they were not trusted by their parents and, at the same time, were too tightly controlled by them. The adolescents did not consider this to be part of a pedagogical parenting style and, as suggested by Kyngäs and Barlow,Citation26 these perceptions might sometimes lead to lies about their self-care as a mechanism to make life more tolerable.

The adolescents sometimes felt they were treated as being younger than they were. Parallels can be drawn to Atkin’s findings in that most of his study participants experienced similar “infantilization” and resented the consequences of this “overprotection” in their lives and relationships.Citation18 In addition, the findings of this present study are substantiated in the World Health Organization’s (WHO’s) paper on adolescents with a chronic condition, which says that the parents of chronically ill adolescents tend to overprotect their chronically ill children.Citation27 In Atkin’s study,Citation18 adolescents also complained that their parents sometimes saw only the illness and not them. This is consistent with the findings of this present study, which revealed the adolescents’ frustrations about their parents’ constant focus on the disease.

Progressive gain of autonomy through ongoing assessment and negotiation was important to the adolescents in this study. Steinberg claims that when children reach adolescence, it is important for parents to encourage and permit their adolescents to develop their own opinions and beliefs.Citation25 Even though Steinberg’s research addresses adolescents in the general population, these findings may also be true for chronically ill adolescents. In addition, the WHO paper on adolescents who have a chronic condition suggests that their individuation processes should be mirrored by progressive distancing on the part of the parents.Citation27 A study of adolescents with chronic diseases asserts that in terms of their child’s health care, the parents should gradually relinquish the “doer” role and simultaneously take on the “mentor” role.Citation28 The findings of this present study revealed that according to the adolescents this does not always happen, so according to the adolescents it seems as if the parents need additional support or education in handling adolescents with CF. These findings resonate with other research on adolescents with CF that suggest that it should be recognized that some parents may need assistance in learning how to support their adolescents. Citation29 Furthermore, another study on adolescents with CF found that parental nagging was a strong predictor of psychological adjustment and suggested that clinicians need to monitor adolescents’ concerns regarding their parents’ care behavior and, where appropriate, offer mediation.Citation21 On the other hand, as premature withdrawal of parental involvement may be associated with poor outcomes and adherence,Citation15,Citation16 it is important that the parents balance involvement and relinquishment.

The adolescents in this present study suggested educating the parents in groups, as they thought their parents could benefit from being with other parents who face similar challenges. This is supported by the research of Kratz et al,Citation30 who found that connecting with peers and cultivating relationships with those in similar situations was helpful and motivating. The findings of this present study, however, also revealed that according to the adolescents, some parents might not require education about parenting.

Previous research has indicated that chronically ill adolescents may not be sufficiently prepared for adult life.Citation8 According to the adolescents in this present study, it seems as if the parents are not sufficiently prepared for their children’s adolescence and transition to adulthood. This may be the case for most parents, but for the parents of adolescents with CF in particular, it may be crucial for the adolescents that their parents know how to support them and hand over the responsibility for the disease and the treatment. It may be a future task for the health professionals to support the parents in letting the adolescent gradually take on the responsibility for the treatment.

Study limitations

The interpretive description of the parents’ needs for education presented in this article is solely based on the adolescent perspective. In order to capture the very complex issue of how to support the transition from child to adult life with CF, the parents’ and the health professionals’ perspectives are important too. Future research is needed to find out whether education is required from the parents’ perspectives as well as the health professionals’ assessment of the need and benefit of such an educational program for CF parents.

The interpretive description is based on data from interviews with Danish adolescents with CF. From an international perspective, we cannot exclude the possibility that adolescent viewpoints might vary in different family cultures and structures. Further, only adolescents affiliated to one of the two Danish CF centers were invited to participate in the interviews, and almost all the participants had attended a CF school – a patient education program, which may have made it easier for the adolescents to get the idea of educating the parents.Citation31 Although the authors of this paper do not claim that this description is the one and only interpretation of the data, they do believe it reflects common thoughts about parenting from young CF patients. The enhancement of credibility was guided by interpretive description evaluation criteria, including epistemological integrity, representative credibility, analytical logic, and interpretive authority,Citation22 and by recommendations regarding rigor of the process and the credibility of the product in secondary analyses.Citation32 Thus, the findings contribute a piece to the puzzle of what kind of parental support may prepare the adolescents sufficiently for adult life.

Conclusion

Preparing adolescents with CF for adult life is a crucial and challenging task. In this study, the adolescents’ opinions about parenting CF adolescents are documented and interpreted, suggesting that the parents need guidance on how to parent and how to hand over the responsibility for the disease and the treatment. In future efforts to support adolescent patients with CF in their transition from child to adult, the elaboration of the patient perspective should be aligned with the perspectives of the parents and the health professionals.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by grants from Roche, Denmark and from the Center of Adolescent Medicine, Rigshospitalet, Copenhagen, Denmark.

Disclosure

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- NavarroJRainisioMHarmsHKFactors associated with poor pulmonary function: cross-sectional analysis of data from the ERCF. European Epidemiologic Registry of Cystic FibrosisJ Eur Respir2001182298305

- KonstanMWMorganWJButlerSMRisk factors for rate of decline in forced expiratory volume in one second in children and adolescents with cystic fibrosisJ Pediatr2007151213413917643762

- WhiteHWolfeSPFoyJNutritional intake and status in children with cystic fibrosis: does age matter?J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr200744111612317204964

- BrittoMTKotagalURHornungRWImpact of recent pulmonary exacerbations on quality of life in patients with cystic fibrosisChest20021211647211796433

- GeeLAbbottJConwaySPEtheringtonCWebbAKQuality of life in cystic fibrosis: the impact of gender, general health perceptions and disease severityJ Cyst Fibros20032420621315463875

- FitzgeraldDNon-compliance in adolescents with chronic lung disease: causative factors and practical approachPaediatr Respir Rev20012326026712052328

- ZindaniGNStreetmanDDStreetmanDSNasrSZAdherence to treatment in children and adolescent patients with cystic fibrosisJ Adolesc Health2006381131716387243

- ZackJJacobsCPKeenanPMPerspectives of patients with cystic fibrosis on preventive counseling and transition to adult carePediatr Pulmonol200336537638314520719

- LaursenBCollinsWAParent-child relationships during adolescenceLernerRMSteinbergLHandbook of Adolescent Psychology. Vol 2: Contextual Influences on Adolescent Development3rd edNew Jersey, USAJohn Wiley and Sons2009342

- BaumrindDCurrent patterns of parental authorityDev Psychol197141 Pt 21103

- DarlingNSteinbergLParenting style as context: an integrative modelPsychol Bull19931133487496

- LilaMvan AkenMMusituGBuelgaSMFamily and adolescenceJacksonSGoossensLHandbook of Adolescent DevelopmentEast Sussex, UKPsychology Press2006154174

- TaylorRMGibsonFFranckLSThe experience of living with a chronic illness during adolescence: a critical review of the literatureJ Clin Nurs200817233083309119012778

- KyngäsHRissanenMSupport as a crucial predictor of good compliance of adolescents with a chronic diseaseJ Clin Nurs200110676777411822848

- ModiACMarcielKKSlaterSKDrotarDQuittnerALThe influence of parental supervision on medical adherence in adolescents with cystic fibrosis: developmental shifts from pre to late adolescenceChildren’s Health Care20083717892

- WysockiTGrecoPSocial support and diabetes management in childhood and adolescence: influence of parents and friendsCurr Diab Rep20066211712216542622

- Botello-HarbaumMNanselTHaynieDLIannottiRJSimons-MortonBResponsive parenting is associated with improved type 1 diabetesrelated quality of lifeChild Care Health Dev200834567568118796059

- AtkinKLiving a “normal” life: young people coping with thalassaemia major or sickle cell disorderSoc Sci Med200153561562611478541

- DeLamboKEIevers-LandisCEDrotarDQuittnerALAssociation of observed family relationship quality and problem-solving skills with treatment adherence in older children and adolescents with cystic fibrosisJ Pediatr Psychol200429534335315187173

- SzyndlerJETownsSJvan AsperenPPMcKayKOPsychological and family functioning and quality of life in adolescents with cystic fibrosisJ Cyst Fibros20054213514415914095

- GraetzBWShuteRHSawyerMGAn Australian study of adolescents with cystic fibrosis: perceived supportive and nonsupportive behaviors from families and friends and psychological adjustmentJ Adolesc Health2000261646910638720

- ThorneSInterpretive DescriptionWalnut Creek, CALeft Coasr Press Inc2008

- ThorneSKirkhamSMacDonald-EmesJFocus on qualitative methods. Interpretive description: a noncategorical qualitative alternative for developing nursing knowledgeRes Nurs Health1997201691779100747

- ThorneSEthical and representational issues in qualitative secondary analysisQual Health Res19988454755510558343

- SteinbergLWe know some things: parent-adolescent relationships in retrospect and prospectJ Res Adolesc2001111119

- KyngäsHBarlowJDiabetes: an adolescent’s perspectiveJ Adv Nurs19952259419478568069

- MichaudPSurisJVinerRWHOThe adolescent with a chronic condition2007 Available from: http://www.who.int/child_adolescent_health/documents/9789241595704/en/Accessed October 22, 2010

- SawyerSDrewSDuncanRAdolescents with chronic disease – the double whammyAust Fam Physician200736862262717676185

- KyngäsHSupport network of adolescents with chronic disease: adolescents’ perspectiveNurs Health Sci20046428729315507049

- KratzLUdingNTrahmsCMVillarealeNKieckheferGMManaging childhood chronic illness: parent perspectives and implications for parent-provider relationshipsFam Syst Health200927430331320047354

- BregnballeV299* Ten years’ of experience in patient education of families with a child/adolescent suffering from cystic fibrosisJ Cyst Fibros20076Suppl 1S73

- ThorneSSecondary analysis in qualitative research: Issues and implicationsMorseJCritical Issues in Qualitative Research MethodsNewbury ParkSage Publications1994263279