Abstract

Three intrauterine devices (IUDs), one copper and two containing the progestin levonorgestrel, are available for use in the United States. IUDs offer higher rates of contraceptive efficacy than nonlong-acting methods, and several studies have demonstrated higher satisfaction rates and continuation rates of any birth control method. This efficacy is not affected by age or parity. The safety of IUDs is well studied, and the risks of pelvic inflammatory disease, perforation, expulsion, and ectopic pregnancy are all of very low incidence. Noncontraceptive benefits include decreased menstrual blood loss, improved dysmenorrhea, improved pelvic pain associated with endometriosis, and protection of the endometrium from hyperplasia. The use of IUDs is accepted in patients with multiple medical problems who may have contraindications to other birth control methods. Yet despite well-published data, concerns and misperceptions still persist, especially among younger populations and nulliparous women. Medical governing bodies advocate for use of IUDs in these populations, as safety and efficacy is unchanged, and IUDs have been shown to decrease unintended pregnancies. Dispersion of accurate information among patients and practitioners is needed to further increase the acceptability and use of IUDs.

Keywords:

Background

The evolution of the intrauterine device (IUD) has led to a safe and effective contraceptive choice for many women. The efficacy in pregnancy prevention far surpasses other daily and scheduled methods such as pills, patches, and contraceptive rings. Satisfaction rates rank high among IUD users in the United States (US) compared to other methods, and complication rates have been shown to be low. The IUD has also emerged as a first-line recommendation for women with heavy bleeding, pelvic pain, and need for menstrual suppression. Yet despite this favorable profile, only 5.5% of women in the US use IUDs.Citation1 Contributing to this low use are the many myths and exaggerated complications that are perpetuated through the media and by practitioners. Lack of knowledge by patients and practitioners regarding noncontraceptive benefits, appropriate candidates for IUDs, and provision of services compounds this problem. The barriers to IUD use need to be addressed so that there is a better understanding of their safety, efficacy, and utility, granting more women access to this beneficial contraceptive choice.

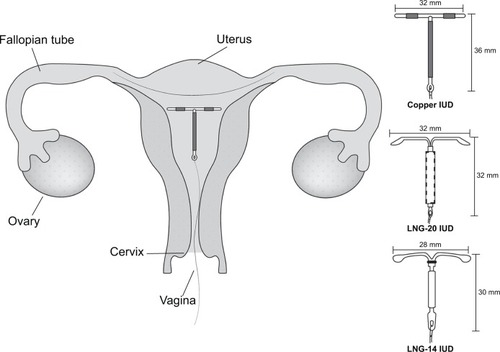

There are three IUDs available for use in the US. Two contain the progestin levonorgestrel (Mirena® and Skyla®, Bayer AG, Leverkusen, Germany). The other is the copper IUD (Paragard®, Teva Pharmaceuticals USA, Sellersville, PA, USA). The copper IUD was developed in 1984 and is a T-shaped device of polyethylene wrapped in a copper wire measuring 36 mm long by 32 mm wide (). It is US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved for 10 years of use.Citation2 Prefertilization effects of the copper ions include inhibition of sperm motility, viability, inhibition of capacitation, destruction of the ovum, and induction of a sterile inflammatory response in the endometrium.Citation3 Postfertilization effects such as damage to the fertilized ovum prior to implantation may occur as well, but most evidence suggests that prefertilization effects constitute the primary mechanism of action.Citation2,Citation4

Figure 1 Dimensions and placement of intrauterine devices.

Abbreviation: IUD, intrauterine device.

The progestin IUDs come in two different sizes, both containing the progestin levonorgestrel (LNG). Mirena®, developed in 2000, is FDA approved for 5 years and contains 52 mg LNG, which is released at 20 μg daily.Citation5 It is hereafter referred to as the LNG-20 IUD. Skyla® was most recently FDA approved in 2013, contains 13.5 mg LNG, and is effective for 3 years of use, releasing 14 μg per day. It is hereafter referred to as the LNG-14 IUD. The LNG-14 IUD is slightly smaller in size, measuring 30 mm long by 28 mm wide, compared to the dimensions of the LNG-20 IUD of 32 mm by 32 mm ().Citation6 To prevent pregnancy, LNG causes suppression of the endometrium, increased amount and viscosity of cervical mucus, and decreases tubal motility. Pre- and postfertilization effects occur before implantation.Citation2 Up to 58%–63% of women may continue to ovulate with LNG IUDs, yet will have decreased menstrual bleeding due to the progestin effect on the endometrium.Citation7

All IUDs are placed through the cervix into the uterine cavity by a trained provider. This procedure is most commonly done in the office, but in special circumstances such as in the case of mentally limited patients and younger adolescents, it can be done under sedation. Menstrual-like cramping is typical for patients to experience during insertion and for the first few days after placement. Nulliparous women in most studies have higher rates of discomfort with placement compared to multiparous patients,Citation8 yet are appropriate candidates for use.Citation9 The use of analgesics such as topical lidocaine, injectable lidocaine, and cervical ripening agents such as misoprostol has been studied without evidence supporting their use for decreased discomfort with insertion.Citation10

Insertion of IUDs has typically been done during menses, but insertion can be performed at any point in the menstrual cycle as long as the practitioner reasonably excludes pregnancy.Citation2 Backup contraception is not needed after copper IUD insertion, but is needed for 7 days after insertion of the LNG IUDs. The exception to this is if the LNG IUD is placed within 5 days of menstrual initiation, or immediately after childbirth, abortion, or switching from an alternative contraceptive method.Citation2,Citation6 Placement is confirmed by a speculum exam performed 2–4 weeks after insertion to visualize the strings protruding from the cervical os. Alternatively, in younger patients or those with mental disability, a pelvic ultrasound can be used to confirm proper placement in the uterine cavity.

Efficacy

Nearly half of the 6.7 million pregnancies reported in the US each year are unintended, and this rate is even higher among 15- to 19-year-old women (82%).Citation11 The contraceptive efficacy of IUDs has been illustrated in many studies. The copper IUD has a reported failure rate at 1 year of 0.8%, and a 10-year failure rate comparable to female sterilization of 1.9 per 100.Citation12 A Cochrane Review evaluating 21 randomized trials concluded that the effectiveness of the LNG-20 IUD is similar to the copper IUD;Citation13 other studies have shown the LNG-20 IUD to be among the most effective contraceptive methods, with a failure rate of 0.1% at 1 year and 0.5% at 5 years, similar to or better than female sterilization.Citation14 Clinical trials of the LNG-14 IUD yielded similar results, showing a cumulative pregnancy rate of 0.9% over 3 years.Citation15

Of great importance is that this efficacy is not altered by or related to patient age. A large landmark study in St Louis, MO, USA grouped the copper IUD, LNG-20 IUD, and another contraceptive method, the subdermal implant, together as long-acting reversible contraceptives (LARCs) and compared them to methods such as the pill, patch, and ring that require patient compliance. Women aged 14–45 years were followed prospectively for 3 years. The failure rate among pill, patch, and ring users was 4.55 per 100 patient-years, compared to only 0.27 per 100 patient-years among IUD and implant users. The risk of unintended pregnancy among LARC users was unaffected by age, whereas the risk for women using pills, patches, or rings was almost twice as high for those younger than 21 years compared with older women.Citation16 It is known that adolescents have higher discontinuation rates of hormonal birth control, putting them at risk for unintended pregnancy.Citation17 Data from the Pregnancy Risk Assessment Monitoring System indicate that 45.2% of young women age 15–19 who experience a live birth have used moderate or very effective methods of contraception in the past, suggesting that these adolescents struggled with adherence.Citation18 It is for this reason that the American College of Obstetrics and Gynecology recommends the use of LARC methods such as LNG IUDs and the copper IUD as first-line methods for contraception in this age group.Citation9

Safety

Due to backlash against IUDs, mainly caused by complications from the Dalkon Shield in the 1970s,Citation2 there are many safety misperceptions that persist with modern-day IUDs. This has greatly impacted the perception that IUDs are not appropriate for nulliparous women or adolescents. As stated previously, not only is the IUD appropriate, but it should be considered first-line for contraception in these populations. Reservations about the incidence of pelvic inflammatory disease (PID) in this population are the most common.Citation19,Citation20 The risk of PID is no greater with IUD use than in the general population. The only initial increase in risk is seen in the first 20 days after insertion. Combined clinical trial data from the World Health Organization found that the development of PID was 6.3 times greater during the first 20 days after IUD insertion,Citation21 which is felt to be due to bacterial contamination from the procedure, and not the IUD specifically. However, after the first 20 days, the risk of infection returns to a baseline of 1.4 per 1,000 women-years throughout 8 years of use. This is the same or lower than the risk of PID in women without IUDs.Citation22–Citation24 In the newer LNG-14 IUD, PID was diagnosed in two out of 1,432 women over the 3-year study period of a clinical trial.Citation15 There is also an argument that LNG IUD use can be preventative to the development of PID. Given that LNG IUDs work to increase cervical mucus and reduce menstrual blood loss, there is less of a risk of bacterial ascension through the cervix into the upper genital tract, and less risk of retrograde menstruation through the fallopian tubes.Citation5,Citation25

The majority of PID infections occur in women under age 25, and women aged 15–24 comprise half of the 18.9 million new cases of sexually transmitted diseases (STDs) in the US each year.Citation26,Citation27 Yet despite this proportionally higher risk, same-day insertion of IUDs can be carried out in all patients, including adolescents, with appropriate screening. All adolescents should undergo STD screening prior to or at the time of insertion. Nucleic acid amplification tests are the most sensitive, and can be done on cervical samples or urine specimens.Citation28 The risk of PID with IUD placement is 0%–5% when insertion occurs with an undetected infection.Citation29 Furthermore, women with positive chlamydia testing after IUD insertion are unlikely to develop PID, even with retention of the IUD, if the infection is treated promptly.Citation30 Based on this data, the US medical eligibility criteria, released by the Centers for Disease Control (CDC), rates IUD use in adolescents as category 2 (), meaning that the benefits outweigh the risks.Citation31 Successful IUD use, even in high-risk populations, is dependent on effective STD screening and follow-up and age-specific counseling.Citation28 Same-day insertion also addresses barriers of lack of transportation and waning motivation in a high-risk population.

Table 1 Conditions acceptable for IUD use based on category of risk 1 or 2

Contraindications for IUD use are listed in . Patients should be assessed for signs and symptoms of PID prior to IUD insertion. If present, insertion should be delayed pending further diagnostic testing. These patients remain candidates for IUD placement in the future, but placement should be delayed until 3 months after the treatment of PID.Citation2

Table 2 Contraindications to IUD use

Along with the exaggerated concern of PID among IUD users comes the concern of infertility associated with IUD use. Worries over infertility are a barrier to IUD use in adolescents when medical providers have been surveyed.Citation32 Reassurance regarding the protection of fertility comes from a landmark study conducted in 2001. This case control study of nulliparous women seeking treatment for primary infertility showed no association between tubal infertility and past IUD use.Citation33 Furthermore, pregnancy rates at 1 year following IUD removal in women under age 30 are equivalent to pregnancy rates in women not using any form of birth control.Citation34

Uterine perforation is a rare complication with IUD insertion. This involves the placement of the IUD through the wall of the uterus, into the peritoneal cavity. The estimated occurrence is 0–1.3 per 1,000 insertions, and surgical removal is recommended if this occurs.Citation35,Citation36 This removal procedure is not an emergency in an asymptomatic patient. The use of another IUD in the future is also not precluded in these patients, though allowing the uterus to heal for 4–6 weeks prior to placement of another IUD is recommended.Citation6 Embedment within the myometrium is also a rare complication. In a study of 75 uterine perforations between 1996–2009, only 9% had difficult removal by pulling on visible strings, suggesting embedment within the myometrium.Citation37 Failure to visualize strings at the cervical os or difficulty with removal should prompt the clinician to assess for uterine perforation or embedment.

Expulsion of IUDs, while still rare, is the most common complication following IUD insertion, and patients should be counseled regarding this possibility prior to placement.Citation38 The available data regarding the LNG-20 IUD and copper IUD report similar expulsions rates for nulliparous and parous women of approximately 5%.Citation39,Citation40 In the LNG-14 IUD clinical trial, the 3-year cumulative expulsion rate was 4.56%.Citation15 Prior expulsion does not preclude placement of another IUD provided that appropriate counseling is given.Citation9

An additional perceived risk with IUD use is that of ectopic pregnancy. This risk is a myth that has been perpetuated, as in fact the use of IUDs decreases the risk of ectopic pregnancy just as IUDs decrease the risk of pregnancy overall.Citation2 The risk of ectopic pregnancy is 0–0.5 per 1,000 women-years among women using IUDs, compared to a rate of 3.25–5.25 per 1,000 women-years among women who do not use contraception.Citation41,Citation42 If a patient does become pregnant with an IUD in place, the proportion of an ectopic pregnancy is higher, although the absolute risk remains low. This is a distinction that needs to be clear during preprocedure counseling. The CDC classifies the use of both the LNG IUD and copper IUD in women with a history of ectopic as a Category 1; no restriction to use ().Citation31

Safety after abortion and placement postpartum has been well studied. The CDC classifies placement of either IUD postabortion or postpartum as either Category 1 or 2.Citation31 Immediate placement after delivery or a second trimester abortion are classified as Category 2 due to the increased risk of expulsion; however, the benefits outweigh the risks.Citation31 If delayed insertion presents a significant barrier to patient care, then immediate or early insertion should be considered. This is especially prudent in adolescent populations, where up to 20% of adolescent mothers give birth again within 2 years.Citation43 It has also been demonstrated that insertion of an IUD immediately after abortion significantly reduces the risk of repeat abortion.Citation44 The exception to postabortion and postpartum insertion is in the event of puerperal sepsis or septic abortions, which are both contraindications to IUD placement (). In both scenarios, placement of IUDs can be performed 3 months following treatment of the infection.Citation2

Noncontraceptive benefits of IUDs

While efficacy in pregnancy prevention makes IUDs a standout among contraceptive choices, the noncontraceptive benefits that come along with IUD use strengthen their marketability, appeal, and use for women seeking less invasive treatment for calamities such as pelvic pain, menorrhagia, endometriosis, and protection from endometrial hyperplasia. As the mechanism of action remains localized to the uterus and cervix, with little if any systemic effect, IUDs are an optimal method for women with multiple medications or medical comorbidities. Common medical conditions for which IUD use is accepted as safe based on CDC guidelines are listed in . Noncontraceptive benefits are summarized in .

Table 3 Noncontraceptive benefits of IUDs

The most highly recognized noncontraceptive benefit is with the use of the LNG-20 IUD to decrease menstrual blood loss. In 2009 the LNG-20 IUD received FDA approval for the treatment of heavy menstrual bleeding. In a review of five studies using the LNG-20 IUD, reductions in measured menstrual blood loss varied from 74%–97% at 12 months of use.Citation45–Citation49 Another case series demonstrated decreased menstrual blood loss by 95% at 6 months of use.Citation50 In studies measuring hemoglobin change among women using the LNG-20 IUD, gain in hemoglobin concentration varied with duration of follow-up, yet all showed a net increase in concentration compared to measurements prior to IUD insertion. Increases in hemoglobin concentration are not found with the copper IUD.Citation51–Citation53 Due to this health benefit, the LNG-20 IUD should be considered over hysterectomy in women with heavy menstrual bleeding without structural anomalies.Citation54 The use of the LNG-20 IUD is less invasive than surgical procedures, posing less risks to patients, and is more cost effective when compared to hysterectomy and endometrial ablation.Citation55,Citation56

There are no dedicated studies to the use of the LNG-20 IUD for the treatment of menorrhagia in adolescent patients, yet the effects on decreased menstrual blood loss can be extrapolated to this population.Citation57 One study that randomized women aged 18–25 years to either the LNG-20 IUD or oral contraceptive pills found significantly higher rates of decreased bleeding in the LNG-20 IUD group.Citation25 A case series of adolescents with bleeding disorders also demonstrated effectiveness of this method to decrease menstrual blood loss in unique populations.Citation58 There are several published studies regarding the use of the LNG-20 IUD in adults with bleeding disorders, resulting in a decrease in menstrual blood loss between 68%–100%.Citation59–Citation61

The newer LNG-14 IUD can also decrease menstrual blood loss, possibly not to the extent of the LNG-20 IUD, although multiple comparative trials are lacking. In Phase II clinical trials comparing the two levonorgestrel IUD doses, both showed increasing rates of amenorrhea over time.Citation15,Citation62 Furthermore, women using the LNG-14 IUD reported 4 days or less of menstrual bleeding per 90-day reference period after 6 months of use.Citation62

Dysmenorrhea, or pain with menses, can also be decreased with the use of the LNG-20 IUD. A recent longitudinal study evaluating 2,102 women found that dysmenorrhea severity was decreased in women using the LNG-20 IUD and oral contraceptive pills. Dysmenorrhea did not change in women using copper IUDs or nonhormonal methods of contraception.Citation63 One would assume that the decrease in dysmenorrhea would also be seen to some extent with the use of the LNG-14 IUD, given that the mechanism of action is the same as the LNG-20 IUD. Further studies are needed to validate this use of the lower dose IUD.

The use of the LNG-20 IUD has also been studied in the treatment of endometriosis-associated pelvic pain. Pilot studies have shown improved control of chronic pelvic pain and dyspareunia in women with endometriosis,Citation64,Citation65 and in women with dysmenorrhea associated with rectovaginal endometriosis.Citation66 Thirty percent of patients showed improvement in endometriosis staging on subsequent laparoscopy after treatment with LNG-20 IUD for 6 months,Citation67 and pain and bleeding decreased after 36 months of follow-up.Citation68

Recent studies have randomized women with endometriosis to either LNG-20 IUD or gonadotropin-releasing hormone agonists (GnRHa),Citation69,Citation70 or expectant management postoperatively.Citation71 In one study randomizing women to either LNG-20 IUD or GnRHa, both treatments were found to be effective in controlling pelvic pain at 6 months,Citation69 however, those randomized to LNG-20 IUD had a continuation rate of 59% at 36 months, and 82% of these women reported a lower pain score compared to the GnRHa group.Citation72 A double-blind study comparing postoperative LNG-20 IUD to expectant management showed decreased dysmenorrhea in the LNG-20 IUD group, and longer time to pain recurrence in this group compared to expectant management.Citation71 A recent Cochrane Review confirmed that while studies are limited, there is consistent evidence showing that postoperative LNG-20 IUD use reduces the recurrence of painful periods in women with endometriosis.Citation73 There are no randomized trials in adolescents with endometriosis, but a retrospective study showed a decrease in pain and bleeding in adolescents using the LNG-20 IUD for treatment of endometriosis.Citation74 This is promising, as endometriosis can be a cause in 25%–38% of adolescents with pelvic pain.Citation75

The progestin effects on the endometrium serve to protect against endometrial hyperplasia. The LNG-20 IUD can be used in women using estrogen replacement therapy, and the protective effects are sustained over the 5-year lifetime of the LNG-20 IUD.Citation6 Studies of this effect using the LNG-14 IUD have not been conducted. Many studies have shown a decreased risk of endometrial cancer in IUD users compared to nonusers, as confirmed by a meta-analysis. Among IUD users (copper and LNG-20 IUD) the pooled odds ratio of endometrial cancer was 0.54 (95% confidence interval [CI], 0.47–0.63).Citation76 The LNG-20 IUD has also been shown to cause regression of endometrial hyperplasia. In a nonrandomized study using the LNG-20 IUD, or oral progestins, or observation, the LNG-20 IUD was the superior treatment for women with simple and atypical endometrial hyperplasia, and no cases progressed to cancer when followed up to 106 months.Citation77 These findings have further been substantiated by a meta-analysis of 24 observational studies, showing better treatment response of endometrial hyperplasia among LNG-20 IUD users compared to oral progestins.Citation78

Protection of the endometrium is important in the adolescent population as well. Approximately 50% of adolescents age 12–19 years are obese,Citation79 and chronic anovulation from unopposed estrogen and polycystic ovarian syndrome are prevalent comorbidities.Citation57 Menstrual regulation and endometrial protection are key to the treatment of anovulation in adolescents, and the LNG-20 IUD serves as optimal therapy in patients who may not be candidates for oral contraceptive pills. Comorbidities such as hypertension, risk of deep venous thrombosis, and malabsorption related to bariatric surgery can limit the use of oral contraceptive pills.Citation57

Along with providing noncontraceptive benefits, all IUDs offer a mechanism of action that poses less interference with systemic illnesses and systemic medications. This includes women with diabetes, vascular disease, smokers, those with history of thrombosis, and those with limited mental capacity.Citation6,Citation57

Patient perspectives

With the evidence now laid regarding effectiveness for contraception, safety of use, and benefits to use, the final question that remains is, “What do patients think?” Patients must be satisfied with their contraceptive method and choose to continue it. Without patient satisfaction and acceptability, all of the other data is useless.

The contraceptive CHOICE project addressed these issues. This recent study provided no-cost contraception to over 9,000 women ages 14–45 years in the city of St Louis, Missouri, USA and surrounding counties. The women received structured counseling regarding contraceptive options; when given the choice, 75% of them chose a LARC option, either IUD or implant. Furthermore, among women under 21 years participating, 69% chose a LARC option.Citation16 This demonstrates that with appropriate counseling of risks and benefits, women will choose the options that are most effective to prevent pregnancy. In this same cohort, satisfaction rates and continuation rates with IUDs were higher than any other method. Among IUD users, the 12-month satisfaction rate for the LNG-20 IUD was 85.7%, which mirrored the 12-month continuation rate of 87.5%. The copper IUD continuation rate was 84% at 12 months, with 80% satisfied. Continuation of the implant, the other LARC method, was 83% at 12 months, with 79% satisfied. Continuation rates of either IUD type were far better than the continuation rates of nonlong-acting methods (pill, patch, ring, injection), which were 55% at 12 months.Citation16,Citation80 Among younger women under the age of 21 years, the LNG-20 IUD had the highest continuation rate of 85%, and the copper IUD had a rate of 75.6% at 12 months, both higher than any nonlong-acting method.Citation15,Citation79

Other studies agree that IUD users report higher satisfaction than users of other methods. One US-based nationwide survey of women age 21–54 showed that overall, 99% of IUD users who continued the method beyond 12 months reported being “very satisfied” or “somewhat satisfied” with the method.Citation81 A study involving postpartum adolescent females using depot medroxyprogesterone acetate (DMPA) injection and the LNG-20 IUD for contraception showed that satisfaction rates did not differ between methods at 6 and 12 months, but the intention to continue the LNG-20 IUD was higher than DMPA. A greater proportion of DMPA users found that the unpredictability and quantity of their bleeding was unacceptable compared with LNG-20 IUD users.Citation82 Another study reviewed satisfaction rates among IUD and implant users age 18 and over, along with reasons for early removal. The LNG-20 IUD had a 74% satisfaction rate, compared to 70% satisfaction with the implant. Of women who had early removal of their IUD, 68% reported pain, 63% reported irregular menses, and 40% reported increased frequency of menstrual bleeding. Nulliparous women were less likely to have early removal compared to multiparous women in this study.Citation83

The most frequently reported reasons for liking IUDs are ease of use, reliability, and for the LNG IUD, lighter menstrual cycles.Citation6 Abnormal bleeding and cramping are the most common reasons for discontinuation of both copper and LNG IUDs. The effect of LNG on the endometrium causes decidualization and thinning over time. This sequence accounts for the initial irregular bleeding pattern that is seen in most users, that improves over time.Citation6 With the newer LNG-14 IUD, clinical trials demonstrated a discontinuation rate of 4.7% over 3 years due to irregular bleeding patterns, including amenorrhea.Citation15 It is imperative then that patients are counseled appropriately regarding expected bleeding patterns with IUD use. Patients must understand that with the LNG IUDs, bleeding may be irregular, but that overall menstrual blood loss will decrease over time. Pelvic pain and cramping must also be addressed as a side effect of any IUD. A study reviewing IUD discontinuation prior to 6 months of use found a discontinuation rate of 7%. Of these patients using the LNG-20 IUD and copper IUD, 27% and 34% stated pelvic pain as the reason for discontinuation, respectively.Citation84

Patients must also be counseled regarding cramping after the procedure itself. This should be done prior to placement, and information with specific details should be given after insertion, such as in . Thorough counseling about expected changes in bleeding patterns before IUD insertion correlates with satisfaction rates and continuation rates.Citation85

Table 4 Post-IUD instructions for patients

Specific considerations

Patient lack of knowledge about IUDs, practitioner counseling, and cost all continue to be barriers to IUD use. This is particularly poignant in their use among nulliparous adolescents and young women. Use of IUDs has increased among sexually experienced adolescents (age 15–19 years) and young women (age 20–24 years) from 2002 to 2010, but still remains under 5%. The use among nulliparous women remains even lower, under 1%.Citation86 This likely reflects the previously discussed misconceptions and restrictions concerning adolescents and nulliparous women. Despite growing evidence and statements from governing bodies such as the American College of Obstetrician and Gynecologists supporting the use of IUDs in these populations, many of these beliefs and barriers still persist.

In some populations, 50% of adolescents have never heard of an IUD.Citation87 Furthermore, counseling from the practitioners that they come in contact with may provide poor or inaccurate information. Approximately one-third to one-half of providers (obstetricians/gynecologists, family medicine physicians, physician assistants, and nurses) believe that IUDs are not appropriate for nulliparous women, and nearly two-thirds do not believe they are appropriate for adolescents.Citation88 Pediatricians are a mainstay in adolescent contraceptive counseling, yet can also be a barrier to IUD use in this population. In one study, 98% of pediatricians surveyed reported that they addressed contraception with their adolescent patients, yet only 19% included discussion of IUDs, and only 10% would recommend an IUD to an adolescent patient. Furthermore, less than 25% recommended that an adolescent should be offered an IUD if she had ever had an STD, had multiple sexual partners, was nulligravid, or was not yet sexually active.Citation32 Time constraints and concerns of parental reaction are often cited as barriers to IUD discussion with adolescents.Citation32 Both are legitimate concerns, and a study of parental acceptability of contraceptive options found that only 18% of those parents surveyed viewed the IUD as an acceptable option for adolescents.Citation89 It is possible that parents view short-acting methods as associated with single sexual episodes, whereas longer-acting methods suggest an ongoing sexual relationship.

The high up-front cost of IUDs is another important barrier to use for women of any age. The average wholesale price of the LNG-20 IUD is $844, and the copper IUD is $718. These figures do not include the office visit cost and procedure cost.Citation90 Provision of no-cost contraception has shown to decrease unintended birth rate, abortions, and repeat abortions.Citation91 In a study among women seeking abortion services, 24% reported the cost of contraception as the reason they did not use a method to prevent pregnancy.Citation92 Another study demonstrated that among women with employer-sponsored health insurance, rates of IUD initiation were higher when cost-sharing was lower, even after accounting for cost-sharing levels of other contraceptive methods.Citation93 These studies are concordant showing that when cost is removed, women are more likely to use long-acting options such as IUDs for contraception. Contraceptive coverage laws continue to change and be debated. As this process evolves, we continue to take note of the efficacy found by programs that provide no-cost contraception.

Conclusion

Despite clear guidelines based on good evidence, adolescents, parents, and clinicians continue to express concerns about IUDs. Some concerns are based on poor evidence or misconceptions; some may be based on truth, and simply require additional counseling or information. Myths affect uptake of these methods among populations that may need this information and access the most.

IUDs are safe and effective in women of any reproductive age. They offer superior contraceptive efficacy, plus noncontraceptive benefits that can improve quality of life in many women. Clear and accurate counseling needs to be provided to patients when choosing a contraceptive method, or when using the IUD for medical indications. The dispersion of accurate information is imperative to the continued use and growing acceptance of this beneficial method.

Disclosure

The author reports no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- MosherWDJonesJUse of contraception in the United States: 1982–2008Vital Health Stat 23201029144

- American College of Obstetricians and GynecologistsACOG Practice Bulletin No. 121: Long-acting reversible contraception: Implants and intrauterine devicesObstet Gynecol2011118118419621691183

- RiveraRYacobsonIGrimesDThe mechanism of action of hormonal contraceptives and intrauterine contraceptive devicesAm J Obstet Gynecol19991815 Pt 11263126910561657

- StanfordJBMikolajczykRTMechanisms of action of intrauterine devices: update and estimation of postfertilization effectsAm J Obstet Gynecol200218761699170812501086

- HubacherDGrimesDANoncontraceptive health benefits of intrauterine devices: a systematic reviewObstet Gynecol Surv200257212012811832788

- BednarekPHJensenJTSafety, efficacy and patient acceptability of the contraceptive and non-contraceptive uses of the LNG-IUSInt J Womens Health20101455821072274

- NilssonCGLähteenmäkiPLLuukkainenTOvarian function in amenorrheic and menstruating users of a levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine deviceFertil Steril198441152556420203

- HubacherDReyesVLilloSZepedaAChenPLCroxattoHPain from copper intrauterine device insertion: randomized trial of prophylactic ibuprofenAm J Obstet Gynecol200619551272127717074548

- ACOG Committee Opinion No. 392, December 2007. Intrauterine device and adolescentsObstet Gynecol200711061493149518055754

- AllenRHBartzDGrimesDAHubacherDO’BrienPInterventions for pain with intrauterine device insertionCochrane Database Syst Rev2009CD00737319588429

- HamiltonBEVenturaSJBirth rates for US teenagers reach historic lows for all age and ethnic groupsNCHS Data Brief20128918

- HatcherRATrussellJNelsonALCatesWJrStewartFHKowalDContraceptive Technology19th rev. edNew York (NY)Ardent Media2007

- FrenchRVan VlietHCowanFHormonally impregnated intrauterine systems (IUSs) versus other forms of reversible contraceptives as effective methods of preventing pregnancyCochrane Database Syst Rev2004CD00177615266453

- TrussellJContraceptive failure in the United StatesContraception201183539740421477680

- NelsonAApterDHauckBTwo low-dose levonorgestrel intrauterine contraceptive systems: a randomized controlled trialObstet Gynecol201312261205121324240244

- WinnerBPeipertJFZhaoQEffectiveness of long-acting reversible contraceptionN Engl J Med2012366211998200722621627

- RaineTRFoster-RosalesAUpadhyayUDOne-year contraceptive continuation and pregnancy in adolescent girls and women initiating hormonal contraceptivesObstet Gynecol20111172 Pt 136337121252751

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC)Sexual experience and contraceptive use among female teens – United States, 1995, 2002, and 2006–2010MMWR. Morb Mortal Wkly Rep2012611729730122552205

- SwansonKJGossettDRFournierMPediatricians’ beliefs and prescribing patterns of adolescent contraception: a provider surveyJ Pediatr Adolesc Gynecol201326634034524075083

- TylerCPWhitemanMKZapataLBCurtisKMHillisSDMarchbanksPAHealth care provider attitudes and practices related to intrauterine devices for nulliparous womenObstet Gynecol2012119476277122433340

- FarleyTMRosenbergMJRowePJChenJHMeirikOIntrauterine devices and pelvic inflammatory disease: an international perspectiveLancet199233987967857881347812

- SimmsIRogersPCharlettAThe rate of diagnosis and demography of pelvic inflammatory disease in general practice: England and WalesInt J STD AIDS199910744845110454179

- WeströmLIncidence, prevalence, and trends of acute pelvic inflammatory disease and its consequences in industrialized countriesAm J Obstet Gynecol19801387 Pt 28808927008604

- GrimesDAIntrauterine device and upper-genital-tract infectionLancet200035692341013101911041414

- SuhonenSHaukkamaaMJakobssonTRauramoIClinical performance of a levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine system and oral contraceptives in young nulliparous women: a comparative studyContraception200469540741215105064

- SuttonMYSternbergMZaidiASt LouisMEMarkowitzLETrends in pelvic inflammatory disease hospital discharges and ambulatory visits, United States, 1985–2001Sex Transm Dis2005321277878416314776

- WeinstockHBermanSCatesWSexually transmitted diseases among American youth: incidence and prevalence estimates, 2000Perspect Sex Reprod Health200436161014982671

- CarrSEspeyEIntrauterine devices and pelvic inflammatory disease among adolescentsJ Adolesc Health2013524 SupplS22S2823535053

- MohllajeeAPCurtisKMPetersonHBDoes insertion and use of an intrauterine device increase the risk of pelvic inflammatory disease among women with sexually transmitted infection? A systematic reviewContraception200673214515316413845

- FaúndesATellesECristofolettiMLFaúndesDCastroSHardyEThe risk of inadvertent intrauterine device insertion in women carriers of endocervical Chlamydia trachomatisContraception19985821051099773265

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC)US Medical Eligibility Criteria for Contraceptive Use, 2010MMWR Recomm Rep201059RR-4186

- WilsonSFStrohsnitterWBaecher-LindLPractices and perceptions among pediatricians regarding adolescent contraception with emphasis on intrauterine contraceptionJ Pediatr Adolesc Gynecol201326528128424012129

- HubacherDLara-RicaldeRTaylorDJGuerra-InfanteFGuzmán-RodríguezRUse of copper intrauterine devices and the risk of tubal infertility among nulligravid womenN Engl J Med2001345856156711529209

- AnderssonKBatarIRyboGReturn to fertility after removal of a levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine device and Nova-TContraception19924665755841493717

- AnderssonKRyde-BlomqvistELindellKOdlindVMilsomIPerforations with intrauterine devices. Report from a Swedish surveyContraception19985742512559649917

- Mechanism of action, safety and efficacy of intrauterine devices. Report of a WHO Scientific GroupWorld Health Organ Tech Rep Ser19877531913118580

- KaislasuoJSuhonenSGisslerMLähteenmäkiPHeikinheimoOUterine perforation caused by intrauterine devices: clinical course and treatmentHum Reprod20132861546155123526304

- RussoJAMillerEGoldMAMyths and misconceptions about long-acting reversible contraception (LARC)J Adolesc Health2013524 SupplS14S2123535052

- HubacherDCopper intrauterine device use by nulliparous women: review of side effectsContraception2007756 SupplS8S1117531622

- BrockmeyerAKishenMWebbAExperience of IUD/IUS insertions and clinical performance in nulliparous women – a pilot studyEur J Contracept Reprod Health Care200813324825418821462

- SivinIDose- and age-dependent ectopic pregnancy risks with intrauterine contraceptionObstet Gynecol19917822912982067778

- SivinISternJHealth during prolonged use of levonorgestrel 20 micrograms/d and the copper TCu 380Ag intrauterine contraceptive devices: a multicenter study. International Committee for Contraception Research (ICCR)Fertil Steril199461170778293847

- BoardmanLAAllsworthJPhippsMGLapaneKLRisk factors for unintended versus intended rapid repeat pregnancies among adolescentsJ Adolesc Health2006394597.e1597.e816982398

- GoodmanSHendlishSKReevesMFFoster-RosalesAImpact of immediate postabortal insertion of intrauterine contraception on repeat abortionContraception200878214314818672116

- IrvineGACampbell-BrownMBLumsdenMAHeikkiläAWalkerJJCameronITRandomised comparative trial of the levonorgestrel intrauterine system and norethisterone for treatment of idiopathic menorrhagiaBr J Obstet Gynaecol199810565925989647148

- BarringtonJWBowen-SimpkinsPThe levonorgestrel intrauterine system in the management of menorrhagiaBr J Obstet Gynaecol199710456146169166207

- CrosignaniPGVercelliniPMosconiPOldaniSCortesiIDe GiorgiOLevonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine device versus hysteroscopic endometrial resection in the treatment of dysfunctional uterine bleedingObstet Gynecol19979022572639241305

- AnderssonJKRyboGLevonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine device in the treatment of menorrhagiaBr J Obstet Gynaecol19909786906942119218

- FedeleLBianchiSRaffaelliRPortueseADortaMTreatment of adenomyosis-associated menorrhagia with a levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine deviceFertil Steril19976834264299314908

- TangGWLoSSLevonorgestrel intrauterine device in the treatment of menorrhagia in Chinese women: efficacy versus acceptabilityContraception19955142312357796588

- AnderssonKOdlindVRyboGLevonorgestrel-releasing and copper-releasing (Nova T) IUDs during five years of use: a randomized comparative trialContraception199449156728137626

- SivinISternJDiazJTwo years of intrauterine contraception with levonorgestrel and with copper: a randomized comparison of the TCu 380Ag and levonorgestrel 20 mcg/day devicesContraception19873532452553111785

- RönnerdagMOdlindVHealth effects of long-term use of the intrauterine levonorgestrel-releasing system. A follow-up study over 12 years of continuous useActa Obstet Gynecol Scand199978871672110468065

- DueholmMLevonorgestrel-IUD should be offered before hysterectomy for abnormal uterine bleeding without uterine structural abnormalities: there are no more excuses!Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand200988121302130419916888

- MarjoribanksJLethabyAFarquharCSurgery versus medical therapy for heavy menstrual bleedingCochrane Database Syst Rev20062CD00385516625593

- HurskainenRTeperiJRissanenPQuality of life and cost-effectiveness of levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine system versus hysterectomy for treatment of menorrhagia: a randomised trialLancet2001357925227327711214131

- BayerLLHillardPJUse of levonorgestrel intrauterine system for medical indications in adolescentsJ Adolesc Health2013524 SupplS54S5823535058

- ChiCPollardDTuddenhamEGKadirRAMenorrhagia in adolescents with inherited bleeding disordersJ Pediatr Adolesc Gynecol201023421522220471874

- ChiCHuqFYKadirRALevonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine system for the management of heavy menstrual bleeding in women with inherited bleeding disorders: long-term follow-upContraception201183324224721310286

- SchaedelZEDolanGPowellMCThe use of the levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine system in the management of menorrhagia in women with hemostatic disordersAm J Obstet Gynecol200519341361136316202726

- LukesASReardonBArepallyGUse of the levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine system in women with hemostatic disordersFertil Steril200890367367718001734

- Gemzell-DanielssonKSchellschmidtIApterDA randomized, phase II study describing the efficacy, bleeding profile, and safety of two low-dose levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine contraceptive systems and MirenaFertil Steril201297361622.e122222193

- LindhIMilsomIThe influence of intrauterine contraception on the prevalence and severity of dysmenorrhea: a longitudinal population studyHum Reprod20132871953196023578948

- VercelliniPAimiGPanazzaSDe GiorgiOPesoleACrosignaniPGA levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine system for the treatment of dysmenorrhea associated with endometriosis: a pilot studyFertil Steril199972350550810519624

- VercelliniPFrontinoGDe GiorgiOAimiGZainaBCrosignaniPGComparison of a levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine device versus expectant management after conservative surgery for symptomatic endometriosis: a pilot studyFertil Steril200380230530912909492

- FedeleLBianchiSZanconatoGPortueseARaffaelliRUse of a levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine device in the treatment of rectovaginal endometriosisFertil Steril200175348548811239528

- LockhatFBEmemboluJOKonjeJCThe evaluation of the effectiveness of an intrauterine-administered progestogen (levonorgestrel) in the symptomatic treatment of endometriosis and in the staging of the diseaseHum Reprod200419117918414688179

- LockhatFBEmemboluJOKonjeJCThe efficacy, side-effects and continuation rates in women with symptomatic endometriosis undergoing treatment with an intra-uterine administered progestogen (levonorgestrel): a 3 year follow-upHum Reprod200520378979315608040

- PettaCAFerrianiRAAbraoMSRandomized clinical trial of a levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine system and a depot GnRH analogue for the treatment of chronic pelvic pain in women with endometriosisHum Reprod20052071993199815790607

- Bayoglu TekinYDilbazBAltinbasSKDilbazSPostoperative medical treatment of chronic pelvic pain related to severe endometriosis: levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine system versus gonadotropin-releasing hormone analogueFertil Steril201195249249620883991

- TanmahasamutPRattanachaiyanontMAngsuwathanaSTechatraisakKIndhavivadhanaSLeerasiriPPostoperative levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine system for pelvic endometriosis-related pain: a randomized controlled trialObstet Gynecol2012119351952622314873

- PettaCAFerrianiRAAbrãoMSA 3-year follow-up of women with endometriosis and pelvic pain users of the levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine systemEur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol2009143212812919181433

- Abou-SettaAMHoustonBAl-InanyHGFarquharCLevonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine device (LNG-IUD) for symptomatic endometriosis following surgeryCochrane Database Syst Rev20131CD00507223440798

- YoostJLaJoieASHertweckPLovelessMUse of the levonorgestrel intrauterine system in adolescents with endometriosisJ Pediatr Adolesc Gynecol201326212012423518190

- American College of Obstetricians and GynecologistsACOG Committee Opinion. Number 310, April 2005. Endometriosis in adolescentsObstet Gynecol2005105492192715802438

- BeiningRMDennisLKSmithEMDokrasAMeta-analysis of intrauterine device use and risk of endometrial cancerAnn Epidemiol200818649249918261926

- ØrboAArnesMHanckeCVereideABPettersenILarsenKTreatment results of endometrial hyperplasia after prospective D-score classification: a follow-up study comparing effect of LNG-IUD and oral progestins versus observation onlyGynecol Oncol20081111687318684496

- GallosIDShehmarMThangaratinamSPapapostolouTKCoomarasamyAGuptaJKOral progestogens vs levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine system for endometrial hyperplasia: a systematic review and meta-analysisAm J Obstet Gynecol20102036547.e1547.e1020934679

- OgdenCLCarrollMDKitBKFlegalKMPrevalence of obesity and trends in body mass index among US children and adolescents, 1999–2010JAMA2012307548349022253364

- PeipertJFZhaoQAllsworthJEContinuation and satisfaction of reversible contraceptionObstet Gynecol201111751105111321508749

- ForrestJDUS women’s perceptions of and attitudes about the IUDObstet Gynecol Surv19965112 SupplS30S348972500

- HowardDLWaymanRStricklandJLSatisfaction with and intention to continue Depo-Provera versus the Mirena IUD among post-partum adolescents through 12 months of follow-upJ Pediatr Adolesc Gynecol201326635836524238267

- DickersonLMDiazVAJordonJSatisfaction, early removal, and side effects associated with long-acting reversible contraceptionFam Med2013451070170724347187

- GrunlohDSCasnerTSecuraGMPeipertJFMaddenTCharacteristics associated with discontinuation of long-acting reversible contraception within the first 6 months of useObstet Gynecol201312261214122124201685

- HillardPJPractical tips for intrauterine devices use in adolescentsJ Adolesc Health2013524 SupplS40S4623535056

- WhitakerAKSiscoKMTomlinsonANDudeAMMartinsSLUse of the intrauterine device among adolescent and young adult women in the United States from 2002 to 2010J Adolesc Health201353340140623763968

- StanwoodNLBradleyKAYoung pregnant women’s knowledge of modern intrauterine devicesObstet Gynecol200610861417142217138775

- KavanaughMLFrohwirthLJermanJPopkinREthierKLong-acting reversible contraception for adolescents and young adults: patient and provider perspectivesJ Pediatr Adolesc Gynecol2013262869523287602

- HartmanLBShaferMAPollackLMWibbelsmanCChangFTebbKPParental acceptability of contraceptive methods offered to their teen during a confidential health care visitJ Adolesc Health201352225125423332493

- EisenbergDMcNicholasCPeipertJFCost as a barrier to long-acting reversible contraceptive (LARC) use in adolescentsJ Adolesc Health2013524 SupplS59S6323535059

- PeipertJFMaddenTAllsworthJESecuraGMPreventing unintended pregnancies by providing no-cost contraceptionObstet Gynecol201212061291129723168752

- HomcoJBPeipertJFSecuraGMLewisVAAllsworthJEReasons for ineffective pre-pregnancy contraception use in patients seeking abortion servicesContraception200980656957419913152

- PaceLEDusetzinaSBFendrickAMKeatingNLDaltonVKThe impact of out-of-pocket costs on the use of intrauterine contraception among women with employer-sponsored insuranceMed Care2013511195996324036995