Abstract

Medication adherence (MA) in adults with type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2D) is associated with improved disease control (glycated hemoglobin, blood pressure, and lipid profile), lower rates of death and diabetes-related complications, increased quality of life, and decreased health care resource utilization. However, there is a paucity of data on the effect of diabetes-related distress, depression, and health-related quality of life on MA. This study examined factors associated with MA in adults with T2D at the primary care level. This was a cross-sectional study conducted in three Malaysian public health clinics, where adults with T2D were recruited consecutively in 2013. We used the 8-item Morisky Medication Adherence Scale (MMAS-8) to assess MA as the main dependent variable. In addition to sociodemographic data, we included diabetes-related distress, depressive symptoms, and health-related quality of life as independent variables. Independent association between the MMAS-8 score and its determinants was done using generalized linear models with a gamma distribution and log link function. The participant response rate was 93.1% (700/752). The majority were female (52.8%), Malay (52.9%), and married (79.1%). About 43% of patients were classified as showing low MA (MMAS-8 score <6). Higher income (adjusted odds ratio 0.90) and depressive symptoms (adjusted odds ratio 0.99) were significant independent determinants of medication non-adherence in young adults with T2D. Low MA in adults with T2D is a prevalent problem. Thus, primary health care providers in public health clinics should focus on MA counselling for adult T2D patients who are younger, have a higher income, and symptoms of depression.

Video abstract

Point your SmartPhone at the code above. If you have a QR code reader the video abstract will appear. Or use:

Introduction

The literature has shown that better medication adherence (MA) is associated with improved disease control (glycated hemoglobin [HbA1c], blood pressure, and lipid profile)Citation1 and decreased health care resource utilization in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2D).Citation2 This has translated into lower health care costs, lower hospitalization rates, fewer diabetes-related complications, increased quality of life, and a lower incidence of death.Citation2–Citation5 In patients with T2D in Denmark,Citation6 a greater proportion of variance in HbA1c levels was related to medication (15.6%) when compared with patients’ sociodemographic characteristics, behavior, perceptions of care, and diabetes-related distress (DRD), which accounted for only 14% of the total variance. The data also show that for every 25% increase in MA, a patient’s HbA1c is reduced by 0.34%.Citation7

However, adherence to medical therapy in general and adherence to medication in particular have posed significant challenges to both health care systems and patients. The prevalence of poor adherence to medication, appointments, screening, diet, exercise, and health behavior is reported to be 30%–40%.Citation8,Citation9 Common reasons for this include the complexity of the drug regimen, fear of side effects, and misperceptions about T2D as an illness.Citation10 Other possible reasons include financial constraints and poor social support for refilling prescriptions,Citation8,Citation11 physical and psychological restrictions affecting daily adherence to prescribed medications, and in particular, increased comorbidity,Citation12 such as complications of T2D,Citation11 visual impairment, diabetic foot problems, health literacy,Citation13 cognitive decline,Citation14 DRD, and depression.Citation15 Physician characteristics and health care settings are other potential factors that may affect patient participation in decision-makingCitation16,Citation17 and MA.Citation18,Citation19

MA is usually defined as the extent to which patients follow the instructions given for prescribed medications.Citation20 Methods used to assess MA include pill counts, pharmacy claims, or refill records, as well as subjective assessment of patient-reported adherence.Citation3 However, there is no consensual standard as to what constitutes adequate adherence; many consider pill count or refill rates >80% to be acceptable.Citation3 Nevertheless, self-reported measures of MA have been increasingly shown to be reliable and valid,Citation21 so are being used increasingly in clinical trials.

Realizing the importance of MA as mentioned above, the opportunity for early disease control in patients with T2D, and the need to prioritize our limited health care resources in the face of the rising T2D epidemic, this study examined the determinants of medication non-adherence in adults with T2D attending public health clinics in Malaysia. We addressed the issue of MA taking into account the effects of DRD, depression, and health-related quality of life (HRQoL) in addition to other sociodemographic and clinical variables. To the best of our knowledge, there is a paucity of data on the association between these variables and MA,Citation2 particularly in an Asian health care setting like Malaysia. Previous similar local studies have not included either DRD or MA,Citation1,Citation22 or used more general measures for stress or health status (eg, the Short Form-36) and not HRQoL measures.Citation23,Citation24 It is hoped that this diagnosable condition of medication non-adherence can become more treatableCitation25 by health care providers based on the findings of this study.

Materials and methods

This study was part of EDDMQoL, a larger cross-sectional study on emotional burden and its effect on disease control, MA, and HRQoL in patients with T2D. The study was conducted from 2012 to 2013. In addition to a questionnaire on demography (age, sex, ethnicity, religion, marital status, educational level, occupation, monthly income), smoking status, and frequency of exercise, we used another structured case record form to capture comorbidity (hypertension and hyperlipidemia/dyslipidemia), diabetes-related complications, duration of diabetes, HbA1c, blood pressure, lipids, number and types of medications used, and MA. In addition to these, we used three additional questionnaires to measure DRD, depression, and HRQoL. These questionnaires were prepared in three languages, ie, English, Malay, and Mandarin.

Setting

Participants were recruited from three public health clinics (Seri Kembangan, Dengkil, and Salak) in Malaysia. These health clinics were specifically chosen because they differ in terms of the characteristics of the patients they serve and the geographical regions in which they are situated. The Seri Kembangan Health Clinic is in an urban area located in the vicinity of Chinese communities, so is visited mainly by Chinese patients. Dengkil Health Clinic is a rural center frequented by larger proportions of Malaysians of Indian origin than for a regular public health clinic. Salak Health Clinic is a rural center in a mainly Malay residential area. The variability of the sites provided a broad range of Asian patients with T2D.

Participants

We consecutively sampled all patients with T2D who came to the clinics for their routine care. The minimum patient age was 30 years and all patients had been diagnosed with T2D more than a year previously. Their records needed to show that they were on regular follow-up, with at least three visits in the past one year and blood tests done within the previous 3 months. We excluded patients who were pregnant or lactating, those who had psychiatric/psychological disorders that could impair judgment and memory, and patients who could not read or understand English, Malay, or Mandarin. Patients who fulfilled the inclusion criteria were approached and informed of the study. Written consent was secured before they answered the questionnaires in the language of their preference. Trained research assistants interviewed patients in their language of preference. Face validity testing in ten patients found the questionnaires to be acceptable and understood without difficulty. This study was approved by the medical research ethics committee at the Ministry of Health, Malaysia.

Medication adherence

The 8-item Morisky Medication Adherence Scale (MMAS-8) enquires about a patient’s experiences with medications during the 2 weeks prior to answering the questionnaire.Citation26 This questionnaire has been translated into different languages so that it can be used with ease among patients in different settings. All the items except item 5 are reverse-coded (no, 0; yes, 1). Item 8 has five options scored in a negative direction from 1 (never) to 5 (always). Items 1–4 and 6–8 are reverse-coded, and item 8 is further divided by 4 when calculating a summated score. The total scale has a range of 0–8, including low adherence (<6), medium adherence (6–7), and high adherence (8). The MMAS-8 scale is reliable (Cronbach’s α=0.83), with a sensitivity of 93% and a specificity of 53%, and is available in the Malay and Chinese languages.Citation26–Citation28 The Malay version of the MMAS-8 showed moderate internal consistency (Cronbach’s α=0.675), and had a test–retest reliability of 0.82 (P<0.001). A significant relationship was found between MMAS-8 categories and HbA1c categories (χ2=20.261; P≤0.001). The Chinese version of the MMAS-8 was also reported to have satisfactory psychometric properties, ie, good internal consistency (Cronbach’s α=0.77) and test–retest reliability (r=0.88, P<0.001).Citation28 Following face validity testing in ten patients, some modifications to the wording of items in the questionnaire were done to refine them and improve understanding.

Health-related quality of life

The World Health Organization Quality of Life-Brief (WHOQOL-BREF)Citation29 produces four HRQoL domains and scores, ie, a physical domain, a psychological domain, a social relationships domain, and an environment domain.Citation29 This four-domain structure, which has a comparative fit index of 0.901, demonstrates good internal consistency, with Cronbach’s α values for each of the four domain scores ranging from 0.66 (for social relationships domain) to 0.84 (for physical domain). There are also two items that are examined separately, ie, question 1, which asks about an individual’s overall perception of quality of life, and question 2, which asks about an individual’s overall perception of his or her health. Domain scores are scaled in a positive direction (ie, higher scores denote higher quality of life).Citation30 Where more than 20% of the data are missing from an assessment, the assessment is discarded. Where up to two items are missing, the mean of the other items in the domain is substituted. Where more than two items are missing from the domain, the domain score is not calculated (with the exception of social relationships domain, where the domain should only be calculated if one or less item is missing). The mean score of items within each domain is used to calculate the domain score. Mean scores are then multiplied by 4 in order to make domain raw scores comparable with the scores used in the WHOQOL-100. The WHOQOL-BREF was shown to be comparable with the WHOQOL-100 in discriminating between ill and well groups. There are high correlations between domain scores based on the WHOQOL-100 and domain scores calculated using items included in the WHOQOL-BREF.Citation29 These correlations ranged from 0.89 (for social relationships domain) to 0.95 (for physical domain). The Malay and Chinese versions of this questionnaire were previously validated and are reported to have satisfactory psychometric properties.Citation31,Citation32

Diabetes-related distress

DRD was measured using the validated 17-item Diabetes Distress Scale (DDS-17).Citation33–Citation35 This instrument assesses problems and difficulties related to diabetes during the past month on a Likert scale from 1 (not a problem) to 6 (a very serious problem).Citation33 Internal reliability of the DDS-17 and the four subscales are adequate (Cronbach’s α>0.87), and validity coefficients yield significant linkages with the Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale, meal planning, exercise, and total cholesterol.Citation33 DDS-17 has been found to have adequate and better psychometric properties compared with other similar scales.Citation34 A mean total score of less than 2.0 indicates little to no distress, a score between 2.0 and 2.9 indicates moderate distress, and 3.0 and greater is considered high distress worthy of clinical attention.Citation36 Those in the moderate and high distress groups have been found to have poorer behavioral and clinical outcomes. A local translation and validation study of the Malay version of the DDS-17 showed high internal consistency (Cronbach’s α=0.94), and the test–retest reliability value was 0.33 (P=0.009). There was a significant relationship between the mean DDS-17 item score categories (<3 versus ≥3) and HbA1c categories (<7% versus ≥7%); χ2=4.20; P=0.048). The Chinese version of the DDS contains 15 items and was found to have good psychometric properties; the Cronbach’s α for internal consistency was 0.90 and the test–retest reliability coefficient was 0.74.Citation35 However, we included all the 17 items in this study in accordance with the original author’s recommendation.

Depression

Depression was defined using the 9-item Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9), which has been shown to have good construct and criterion validity in making the diagnosis and assessing the severity of depression.Citation37–Citation39 The PHQ-9 refers to symptoms experienced by patients during the last 2 weeks (eg, “thoughts that you would be better off dead or of hurting yourself in some way”). The PHQ-9 has nine items that are scored from 0 (not at all) to 3 (nearly every day), giving a total score that ranges from 0 to 27. The PHQ-9 has cut-off points at scores of 5, 10, 15, and 20, representing mild, moderate, moderately severe, and severe depression, respectively. A total score of ≥10 indicates a sensitivity of 88% and a specificity of 89% for major depression.Citation37 The Malay version of the PHQ-9 had been locally validated and found to have a sensitivity of 87% (95% confidence interval [CI] 71–95), a specificity of 82% (95% CI 74–88), a positive likelihood ratio of 4.8 (3.2–7.2), and a negative likelihood ratio of 0.16 (0.06–0.40).Citation38 The Chinese version of the PHQ-9 is reported to have good psychometric properties, with an internal consistency of 0.82 and test–retest reliability over a 2-week interval of 0.76.Citation39

Clinical variables

T2D was defined as present when the patients’ case records showed the following criteria: documented diagnosis of diabetes mellitus according to the 1999 World Health Organization criteria,Citation40 current treatment consisting of lifestyle modification, or on oral antihyperglycemic agents or insulin. Hypertension is diagnosed if systolic blood pressure is ≥130 mmHg or diastolic blood pressure is ≥80 mmHg on each of two successive readings obtained by the clinic physician.Citation41 A blood pressure <130/80 mmHg was regarded as controlled, and this was the mean of two readings in the rested position with the arm at heart level, using a cuff of appropriate size. Hyperlipidemia refers to an increase in concentration of one or more plasma or serum lipids, usually cholesterol and triglycerides, and the term dyslipidemia is used for either an increase or decrease in concentration of one or more plasma or serum lipids (low-density lipoprotein cholesterol >2.6 mmol/L, triglycerides >1.7 mmol/L, and high-density lipoprotein cholesterol <1.1 mmol/L). Body mass index is calculated as weight divided by height squared. Low-density lipoprotein-cholesterol ≤2.6 mmol/L and HbA1c ≤6.5% are regarded as the other treatment targets.Citation41,Citation42 These clinical data were retrieved from the patient’s medical record using a case record form on the day that the patient completed the questionnaires.

Diabetes-related complications

There were five diabetes-related complications in this study; three were classified as microvascular complications, comprising retinopathy, nephropathy, and diabetic foot problems, and two were classified as macrovascular complications, ie, ischemic heart disease and cerebrovascular disease or stroke. These complications were retrieved from patient records. Diagnoses of these complications were made or confirmed by the attending physician at the clinic based on medical symptoms, laboratory results, radiological evidence, and treatment history at the clinic and other hospitals. Nephropathy was diagnosed as the persistent presence (on two or more occasions at least 3 months apart) of any of the following: microalbuminuria, proteinuria, serum creatinine >150 mmol/L, or estimated glomerular filtration rate <60 mL per minute (calculated using the Cockcroft-Gault formula). Diabetic foot problems comprised foot deformity that is related to the lower limbs muscle weakness and/or as a consequence of the other diabetic foot problems, current ulcer, amputation, peripheral neuropathy, or peripheral vascular disease.

Statistical analysis

The sample size was calculated using G*Power 3.1.2 software,Citation43 with an estimated effect size of r=0.16 between DRD and HbA1c,Citation44,Citation45 a power of 0.95, and significance at 0.05; the estimated sample size was 500. Taking into consideration about 30% of data being incomplete/missing in patient medical records and 30% of questionnaires returned from patients being incomplete, the sample size needed was 650.

Quantitative data analyses were done using PASW version 21.0 (SPSS Inc, Chicago, IL, USA). Differences in the categorical variables were performed using the Chi-squared test. P<0.05 was considered to be significant at two tails. To analyze the association of the demographic and clinical variables and MA, generalized linear models were used with MMAS-8 total score as the outcome variable. Since the MMAS-8 total score was skewed to the left, a generalized linear model with a gamma distribution and log link function was used. The gamma distribution is a reasonable choice because its flexible distribution accommodates well for positive and continuous variables and it incorporates the assumption that the standard deviation is proportional to the mean. Univariable analyses were done for the independent variables and those that showed significant effects on the MMAS-8 total scores were included in the final multivariable generalized linear model analyses. In the final model, normality of residual was confirmed, as residual plots indicated fulfilment of linearity and homogeneity assumptions, and model fitting encountered no obvious problem as evidenced by the residual deviance being less than the residual degree of freedom.

Results

The participant response rate was 93.1% (700/752). From this number of participants, we had 668 completed MMAS-8 questionnaires. More than half were female (52.8%) and Malay (52.9%, ). The majority were married or living with a partner (79.1%), had non-tertiary education (89.1%), and were earning <RM 3,000 per month (94.4%); most of the patients were non-smokers and undertook some exercise; about 80% reported having hypertension but antihypertensive usage was almost 90% ().

Table 1 Patient characteristics according to medication adherence categories

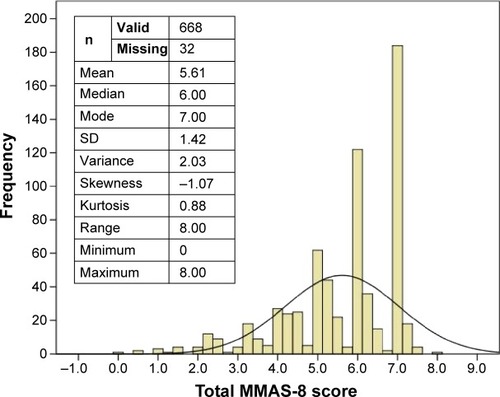

shows the distribution of the total MMAS-8 score. About 43% and 57% of the patients were classified as low (MMAS-8 score <6) and medium to high (MMAS-8 score 6–8) MA categories, respectively. The mean (± standard deviation) for age was 56.9±10.18 years. The median (interquartile range) scores for the DDS-17, PHQ-9, duration of diabetes, hypertension, and dyslipidemia were 33.0 (24.00 to 47.00), 4.0 (1.00 to 7.00), 4.0 (3.00 to 9.00), 5.0 (3.00 to 9.00) and 3.0 (2.00 to 6.00), respectively.

Figure 1 Distribution of MMAS-8 total score.

shows the univariable (crude odds ratio) and multivariable (adjusted odds ratio) analyses for the significant variables. It was observed that younger age, Malay ethnicity, higher income, higher education, exercise ≤3 times per week, lower overall HRQoL, higher DRD, and depressive symptoms were associated with poor MA. After adjustment for all these variables, being a younger adult with T2D, higher income, and depressive symptoms were significant independent determinants of non-adherence with medication.

Table 2 Determinants of medication adherence

Discussion

This study reports on the determinants of MA in adult T2D patients taking into account DRD, depression, and quality of life, which were not investigated in previous studies.Citation1,Citation22–Citation24 We noted a similar prevalence of low MA among adult T2D patients in this study, which is in line with earlier studies, ie, 40%–50% locally,Citation1,Citation22 and 40%–90% elsewhere, varied by whether the participants were on oral hypoglycemic or insulin medication.Citation46,Citation47

Strong determinants for medication non-adherence, such as younger age, higher income, higher education, less adherence to exercise recommendations, poorer HRQoL, having DRD, and depression were expected and have been reported previously.Citation1,Citation22 However, it was unexpected that those who did not exercise at all were as adherent to medication as those who exercised more than three times per week. Clustering of healthy behaviors has been reported before, and it would be expected that patients who adhered to exercise recommendations would also adhere to their prescribed medication.Citation48 However, this finding might be limited by the brevity of this self-reported variable and the lack of simultaneous measurement of other healthy behaviors, such as dietary habits, self-monitoring of blood glucose, and adherence to blood testing.Citation4

That adult T2D patients of Indian ethnicity were more adherent to their medication compared with the Malay and Chinese patients was unexpected.Citation22 Chinese patients are believed to be more health conscious and adherent to health recommendations such as exercise.Citation49 The Chinese are also often thought to be more adherent to their medication as prescribed by their physicians.Citation48 However, being in a higher income group and having higher DRD might influence their adherence to prescribed medication. Having higher income possibly enables them to be more resourceful in health-seeking endeavors. In comparison with Indians, Malay patients were more likely to have tried other traditional therapiesCitation50 and the Chinese more often sought further private medical opinionsCitation51 for their T2D. These might have resulted in the observed higher non-adherence among Malay and Chinese patients to their medication when compared with Indians. However, this ethnic disparity in MA became statistically insignificant after adjustment for the stronger influence of income, age, and depression. Higher MA among Indians could also have been due to the lower prevalence of moderate to severe depression (7.5%) compared with the other two ethnic groups (12.0%; data not reported in the study).

Unlike many Western studies that have reported an association of medication non-adherence with DRD instead of depression,Citation52–Citation54 our results indicated a stronger adjusted effect of depression, rather than DRD, on medication non-adherence. This was probably due to the nature of DRD, which has milder symptomatologyCitation55 or because patients with DRD could manifest a psychological reaction of being successful in coping with MA rather than failing.Citation56

The fact that medication use and insulin use did not affect MA is in line with a previous study that was also done in public health clinics,Citation22 but in contrast with another study showing that patients on insulin and oral hypoglycemic agents were predisposed to medication non-adherence.Citation1 However, this latter study was conducted in an urban academic hospital, a setting that is different from the studies at the primary care level.Citation57 Nevertheless, a similar finding was noted with regard to unemployment status in association with medication non-adherence which reached statistical significance in that study, but not in this study. This could have been due to the higher drug cost required to refill prescriptions in the academic hospital, and thus the patients were predisposed to medication non-adherence.Citation58 Having comorbidity such as hypertension, dyslipidemia,Citation22 or diabetes-related complications also did not affect MA in adults with T2D attending public health clinics.Citation22 On the contrary, after being diagnosed with these comorbidities and complications, there were greater proportions of patients who reported higher MA. This result confirms many primary care physicians’ experience and assumption that many of their patients become “better” patients in terms of adhering to therapeutic recommendations and their monitoring schedule after being diagnosed with an additional comorbidity or complication.

For T2D patients who are at risk of medication non-adherence, a poly-pill approach might be a helpful adjunctCitation59 to other strategies, including reducing treatment complexity, decreasing pill burden, and addressing patient and socioeconomic issues that contribute to the problem.Citation60,Citation61 Future studies should look into adherence behavior over time and the ability of primary care physician to screen and respond to medication non-adherence.Citation62

One of the limitations of this study lies in the use of a single measure for MA assessment, ie, the MMAS-8. This might predispose to recall bias or a biased response in the presence of significant others during the interview. However, since this was part of a larger study and used a locally validated MMAS-8 in a large sample size, we believe the design was able to produce a valid evaluation of determinants of MA. It would be desirable in a future study to have more than one measure for MA, such as pill count in addition to a self-report measure. The strength of the study was its representative sample of patients, in terms of their sociodemographic background being similar to the adult T2D patients in public health clinics throughout the whole country.Citation63

Conclusion

Low MA is a serious problem in adult patients with T2D, and its downstream effects will be multiplied in increased complication rates, psychological burden, and health care costs if left unaddressed. Primary health care providers in public health clinics should focus on MA counselling for adult T2D patients of younger age, with a higher income, and who report more depressive symptoms. This study provides further evidence regarding the characteristics of patients who may be at risk for medication non-adherence. This behavior did not differ according to ethnic groups, number and types of medication prescribed, or duration of diabetes and comorbidities/complications.

Acknowledgments

This study was funded by the Research University Grants Scheme 2 (RUGS/04-02-2105RU). We acknowledge Al-Qazaz et al, Morisky et al, the World Health Organization, Polonsky et al, Sherina Mohd-Sidik, and Xiaonan Yu for the use of the different versions of the MMAS-8, WHOQOL-BREF, DDS-17, and PHQ-9 questionnaires. In addition, we are grateful to the Sepang and Petaling district health offices and officers for their support of this study, and the Director General of Health for permission to publish the findings. We thank Firdaus Mukhtar, Nor-Kasmawati Jamaludin, and Fuziah Paimin for their input during the planning of the study and their assistance with data collection. We would also like to thank the staff members of all the clinics for facilitating the data collection process.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work. The study sponsor had no role in the design or conduct of the study, the writing of this report, or the decision to submit it for publication.

References

- ChuaSSChanSPMedication adherence and achievement of glycaemic targets in ambulatory type 2 diabetic patientsJournal of Applied Pharmaceutical Science201115559

- AscheCLaFleurJConnerCA review of diabetes treatment adherence and the association with clinical and economic outcomesClin Ther2011337410921397776

- OsterbergLBlaschkeTAdherence to medicationN Engl J Med200535348749716079372

- LianJLiangYDiabetes management in the real world and the impact of adherence to guideline recommendationsCurr Med Res Opin2014302233224025105305

- WildHThe economic rationale for adherence in the treatment of type 2 diabetes mellitusAm J Manag Care201218S43S4822558941

- RogviSTapagerIAlmdalTPSchiotzMLWillaingIPatient factors and glycaemic control – associations and explanatory powerDiabet Med201229e382e38922540962

- RheeMKSlocumWZiemerDCPatient adherence improves glycemic controlDiabetes Educ20053124025015797853

- DiMatteoMRVariations in patients’ adherence to medical recommendations: a quantitative review of 50 years of researchMed Care20044220020915076819

- CramerJABenedictAMuszbekNKeskinaslanAKhanZMThe significance of compliance and persistence in the treatment of diabetes, hypertension and dyslipidaemia: a reviewInt J Clin Pract200862768717983433

- WeinmanJPetrieKJIllness perceptions: a new paradigm for psychosomatics?J Psychosom Res1997421131169076639

- AholaAJGroopPHBarriers to self-management of diabetesDiabet Med20133041342023278342

- BalkrishnanRRajagopalanRCamachoFTHustonSAMurrayFTAndersonRTPredictors of medication adherence and associated health care costs in an older population with type 2 diabetes mellitus: a longitudinal cohort studyClin Ther2003252958297114693318

- NgohLNHealth literacy: a barrier to pharmacist-patient communication and medication adherenceJ Am Pharm Assoc (2003)200949e132e14619748861

- AndersonKJueSGMadaras-KellyKJIdentifying patients at risk for medication mismanagement: using cognitive screens to predict a patient’s accuracy in filling a pillboxConsult Pharm20082345947218764676

- ZhangJXuCPWuHXComparative study of the influence of diabetes distress and depression on treatment adherence in Chinese patients with type 2 diabetes: a cross-sectional survey in the People’s Republic of ChinaNeuropsychiatr Dis Treat201391289129424039431

- AndersonLAHealth care communication and selected psychosocial correlates of adherence in diabetes managementDiabetes Care1990136676

- ParchmanMLZeberJEPalmerRFParticipatory decision making, patient activation, medication adherence, and intermediate clinical outcomes in type 2 diabetes: a STARNet studyAnn Fam Med2010841041720843882

- DiMatteoMRSherbourneCDHaysRDPhysicians’ characteristics influence patients’ adherence to medical treatment: results from the Medical Outcomes StudyHealth Psychol199312931028500445

- KaissiAAParchmanMOrganizational factors associated with self-management behaviors in diabetes primary care clinicsDiabetes Educ20093584385019783769

- CramerJARoyABurrellAMedication compliance and persistence: terminology and definitionsValue Health200811444718237359

- GarfieldSCliffordSEliassonLBarberNWillsonASuitability of measures of self-reported medication adherence for routine clinical use: a systematic reviewBMC Med Res Methodol20111114922050830

- AhmadNSRamliAIslahudinFParaidathathuTMedication adherence in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus treated at primary health clinics in MalaysiaPatient Prefer Adherence2013752553023814461

- KaurGTeeGHAriaratnamSKrishnapillaiASChinaKDepression, anxiety and stress symptoms among diabetics in Malaysia: a cross sectional study in an urban primary care settingBMC Fam Pract2013146923710584

- CheahWLLeePYLimPYFatin NabilaAALukKJNur IrwanaATPerception of quality of life among people with diabetesMalays Fam Physician20127213025606252

- MarcumZASevickMHandlerSMMedication nonadherence: a diagnosable and treatable medical conditionJAMA20133092105210623695479

- MoriskyDEAngAKrousel-WoodMWardHJPredictive validity of a medication adherence measure in an outpatient settingJ Clin Hypertens (Greenwich)20081034835418453793

- Al-QazazHKHassaliMAShafieAASulaimanSASundramSMoriskyDEThe eight-item Morisky Medication Adherence Scale MMAS: translation and validation of the Malaysian versionDiabetes Res Clin Pract20109021622120832888

- YanJYouLMYangQTranslation and validation of a Chinese version of the 8-item Morisky Medication Adherence Scale in myocardial infarction patientsJ Eval Clin Pract201420431131724813538

- SkevingtonSMLotfyMO’ConnellKAThe World Health Organization’s WHOQOL-BREF quality of life assessment: psychometric properties and results of the international field trial. A report from the WHOQOL groupQual Life Res20041329931015085902

- No authors listedDevelopment of the World Health Organization WHOQOL-BREF quality of life assessment. The WHOQOL GroupPsychol Med1998285515589626712

- YaoGChungCWYuCFWangJDDevelopment and verification of validity and reliability of the WHOQOL-BREF Taiwan versionJ Formos Med Assoc200210134235112101852

- HasanahCINaingLRahmanARWorld Health Organization Quality of Life Assessment: brief version in Bahasa MalaysiaMed J Malaysia200358798814556329

- PolonskyWHFisherLEarlesJAssessing psychosocial distress in diabetes: development of the Diabetes Distress ScaleDiabetes Care20052862663115735199

- El AchhabYNejjariCChikriMLyoussiBDisease-specific health-related quality of life instruments among adults diabetic: a systematic reviewDiabetes Res Clin Pract20088017118418279993

- TingRZNanHYuMWDiabetes-related distress and physical and psychological health in Chinese type 2 diabetic patientsDiabetes Care2011341094109621398526

- FisherLHesslerDMPolonskyWHMullanJWhen is diabetes distress clinically meaningful? Establishing cut points for the Diabetes Distress ScaleDiabetes Care20123525926422228744

- KroenkeKSpitzerRLWilliamsJBThe PHQ-9: validity of a brief depression severity measureJ Gen Intern Med20011660661311556941

- SherinaMSArrollBGoodyear-SmithFCriterion validity of the PHQ-9 (Malay version) in a primary care clinic in MalaysiaMed J Malaysia20126730931523082424

- YuXTamWWWongPTLamTHStewartSMThe Patient Health Questionnaire-9 for measuring depressive symptoms among the general population in Hong KongCompr Psychiatry2012539510221193179

- World Health OrganizationDefinition, diagnosis and classification of diabetes mellitus and its complicationsPart 1: diagnosis and classification of diabetes mellitus. Report no. 99.2Geneva, SwitzerlandWorld Health Organization1999 Available from: http://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/66040Accessed April 6, 2015

- Ministry of Health MalaysiaManagement of type 2 diabetes mellitusPutrajaya, MalaysiaTechnology, Health Section, Assessment Division, Medical Development2009 Available from: http://www.moh.gov.my/attachments/3878.pdfAccessed April 7, 2015

- American Diabetes AssociationStandards of medical care in diabetes – 2015Diabetes Care201538Suppl 1S1S9325537700

- FaulFErdfelderELangAGBuchnerAG*Power 3: a flexible statistical power analysis program for the social, behavioral, and biomedical sciencesBehav Res Methods20073917519117695343

- FisherLMullanJTAreanPGlasgowREHesslerDMasharaniUDiabetes distress but not clinical depression or depressive symptoms is associated with glycemic control in both cross-sectional and longitudinal analysesDiabetes Care201033232819837786

- van BastelaarKMPouwerFGeelhoed-DuijvestijnPHDiabetes-specific emotional distress mediates the association between depressive symptoms and glycaemic control in type 1 and type 2 diabetesDiabet Med20102779880320636961

- CramerJAA systematic review of adherence with medications for diabetesDiabetes Care2004271218122415111553

- SalehFMumuSJAraFHafezMAAliLNon-adherence to self-care practices and medication and health related quality of life among patients with type 2 diabetes: a cross-sectional studyBMC Public Health20141443124885315

- Jimenez-GarciaREsteban-HernandezJHernandez-BarreraVJimenez-TrujilloILopez-de-AndresACarrasco GarridoPClustering of unhealthy lifestyle behaviors is associated with nonadherence to clinical preventive recommendations among adults with diabetesJ Diabetes Complications20112510711320554450

- ChewBHKhooEMChiaYCQuality of care for adult type 2 diabetes mellitus at a university primary care centre in MalaysiaInt J Collab Res Intern Med Public Health20113439449

- ChingSMZakariaZAPaiminFJalalianMComplementary alternative medicine use among patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus in the primary care setting: a cross-sectional study in MalaysiaBMC Complement Altern Med20131314823802882

- OmarMTongSFSalehNA comparison of morbidity patterns in public and private primary care clinics in MalaysiaMalays Fam Physician20116192525606215

- WalkerRJSmallsBLHernandez-TejadaMACampbellJADavisKSEgedeLEEffect of diabetes fatalism on medication adherence and self-care behaviors in adults with diabetesGen Hosp Psychiatry20123459860322898447

- AikensJEProspective associations between emotional distress and poor outcomes in type 2 diabetesDiabetes Care2012352472247823033244

- GonzalezJSShreckEPsarosCSafrenSADistress and type 2 diabetes treatment adherence: a mediating role for perceived controlHealth Psychol8112014 Epub ahead of print

- FisherLGonzalezJSPolonskyWHThe confusing tale of depression and distress in patients with diabetes: a call for greater clarity and precisionDiabet Med20143176477224606397

- KarlsenBOftedalBBruEThe relationship between clinical indicators, coping styles, perceived support and diabetes-related distress among adults with type 2 diabetesJ Adv Nurs20126839140121707728

- ChewBHShariff-GhazaliSLeePYType 2 diabetes mellitus patient profiles, diseases control and complications at four public health facilities-a cross-sectional study based on the Adult Diabetes Control and Management (ADCM) Registry 2009Med J Malaysia20136839740424632869

- PietteJDWagnerTHPotterMBSchillingerDHealth insurance status, cost-related medication underuse, and outcomes among diabetes patients in three systems of careMed Care20044210210914734946

- CastellanoJMSanzGPenalvoJLA polypill strategy to improve adherence: results from FOCUS (Fixed-dose Combination Drug for Secondary Cardiovascular Prevention) ProjectJ Am Coll Cardiol2014642071208225193393

- VermeireEWensJVan RoyenPBiotYHearnshawHLindenmeyerAInterventions for improving adherence to treatment recommendations in people with type 2 diabetes mellitusCochrane Database Syst Rev20052CD00363815846672

- BaileyCJKodackMPatient adherence to medication requirements for therapy of type 2 diabetesInt J Clin Pract20116531432221314869

- National Institute for Health and Care ExcellenceMedicines adherence: Involving patients in decisions about prescribed medicines and supporting adherence. Clinical guideline 76Manchester, UKNational Institute for Health and Care Excellence2009 Available from: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg76Accessed April 8, 2015

- Non-Communicable Disease Section, Disease Control Division, Department of Public HealthNational Diabetes Registry Report12009–2012 Available from: file:///C:/Users/susan/Downloads/National_Diabetes_Registry_Report_Vol_1_2009_2012.pdfAccessed April 7, 2015