Abstract

Objectives

The risk for many chronic diseases increases with obesity. In addition to these, the risk for depression also increases. Exercise interventions for weight loss among those who are not overweight or obese have shown a moderate effect on depression, but few studies have looked at those with obesity. The objectives of this study were to determine 1) the prevalence of depressed mood in obese participants as determined by the Beck Depression Inventory II at baseline and follow-up; 2) the change in depressed mood between those who completed the program and those who did not; and 3) the differences between those whose depressed mood was alleviated after the program and those who continued to have depressed mood.

Methods

Depressed mood scores were calculated at baseline and follow-up for those who completed the program and for those who quit. Among those who completed the program, chi-squares were used to determine the differences between those who no longer had depressed mood and those who still had depressed mood at the end of the program, and regression analysis was used to determine the independent risk factors for still having depressed mood at program completion.

Results

Depressed mood prevalence decreased from 45.7% to 11.7% (P<0.000) from baseline to follow-up among those who completed the program and increased from 44.8% to 55.6% (P<0.000) among those who quit. After logistic regression, a score of <40 in general health increased the risk of still having depressed mood upon program completion (odds ratio [OR] 3.39; 95% CI 1.18–9.72; P=0.023).

Conclusion

Treating depressed mood among obese adults through a community-based, weight-loss program based on evidence may be an adjunct to medical treatment. More research is needed.

Introduction

Obesity is difficult to treat. It is the result of complex environmental, socioeconomic, and lifestyle factors.Citation1–Citation6 As such, the prevalence rate of obesity has more than tripled in Canada in the past 30 years.Citation7 Complexities in treatment arise when obese patients have comorbidities, which is often the case.Citation8 The risk for cardiovascular disease,Citation9,Citation10 diabetes,Citation11 cancers,Citation12–Citation14 and premature mortalityCitation15–Citation21 increases with obesity.

In addition to these, the risk for depression also increases. For example, among a nationally representative sample of 9,125 American adults, it was found that having a body mass index (BMI) of >30 kg/m2 increased the risk of having a lifetime mood disorder by 25% after adjusting for age, sex, smoking, and other psychiatric disorders.Citation22 This increased risk is highly problematic, especially when it is overlooked by health care professionals, as depression has been identified as a barrier to obesity treatment.Citation23–Citation25

The prevalence of depression among obese adults in previous research has ranged depending on the methodology. For example, Onyike et alCitation26 evaluated data from 1988 to 1994 using Diagnostic Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Third Edition (DSM-III), diagnostic criteria for depression and found a prevalence of 5.1% among obese adults (within the past month), while Roberts et alCitation27 evaluated data from 1994 to 1995 using Diagnostic Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition (DSM-IV), criteria and found a 15.5% prevalence of depression among obese adults (within the past 2 weeks). In a recent report by the National Center for Health Statistics, the age-adjusted prevalence of moderate depression among obese adults was 42.7% from 2005 to 2010.Citation28

Depression and obesity are closely linked. The relationship appears to be bidirectional, with much discussion in the literature for potential pathways.Citation29 For example, eating behaviors associated with depression have been linked to obesity, such as emotional eatingCitation30 and night eating.Citation31 Additionally, the use of mood stabilizers such as antidepressants may cause a person to gain weight.Citation32 Negative effects associated with being overweight or obese may also trigger depressive symptoms.Citation29

Cross-sectional studies have found differences in the relationship between obesity and depression among men compared to women and among those with severe obesity. A study analyzing data from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey found a significant association between obesity and depression in women, but not in men. The authors also found that those with severe obesity (BMI ≥40) were four times more likely to be depressed, even after controlling for many demographic and behavioral factors.Citation26

In a meta-analysis of longitudinal studies on the relationship between depression and overweight and obesity, it was found that baseline obesity increased the onset of depression by 55%, and being overweight increased the risk of onset of depression by 27%. Furthermore, the study found that depression also increased the risk of developing obesity by 58%.Citation33

The good news is that weight loss can positively impact mood. In a study of 487 patients who underwent gastric-restrictive weight loss surgery, it was found that losing weight after the surgery was associated with a significant and sustained drop in depressed mood scores, at 1-year and 4-year follow-up.Citation34 This narrowly focuses on surgery/weight loss and depressed mood. The impact of other interventions to improve weight has had small to moderate, but positive, results on depression. For example, the Cochrane Collaboration reviewed 35 trials with 1,356 participants to determine the impact of exercise on depression. The authors concluded that there is only a moderate effect of exercise on depression, and there are too few quality trials.Citation35 Essentially, the research is too early to be definitive. In addition, this review excluded studies with participants who were overweight or obese or those who had only depressed mood, rather than depression. Perhaps the effect would be larger among those who are depressed but are also suffering from obesity.

It is appropriate for an obese person to be treated in a clinician’s office or by a commercial weight loss program. The Healthy Weights Initiative in Moose Jaw, Saskatchewan, is a community-based, obesity reduction program that adheres to the ten principles outlined by the International Obesity Task Force and the Guidelines for Managing Overweight and Obesity in Adults (2013), which recommend intensive, multi-component behavioral intervention to address obesity and its related health effects.Citation36 The first objective is to determine the prevalence and severity of depressed mood in obese participants as determined by a validated instrument at baseline and follow-up for the first five waves of participants. The second objective is to determine the change in depressed mood between those who completed the program and those who did not. The third objective is to determine the differences between those whose depressed mood was alleviated after the program and those who continued to have depressed mood.

Methods

Setting

According to data from Statistics Canada, there are ~5,000 adults living in the city of Moose Jaw, Saskatchewan, Canada, who are obese.Citation37

Participants

Adults with a BMI ≥30 kg/m2 who were referred to the program by a medical doctor were eligible to participate. Participants received a medical screen by their family physician to ensure safety to participate. No other inclusion or exclusion criteria were applied. This study was deemed exempt from ethical approval by the University of Saskatchewan Behavioural Ethics Board. As this study met the requirements for exemption status per Article 2.5 of the Tri-Council Policy Statement: Ethical Conduct for Research Involving Humans, December 2014, participant consent was not sought.

Measures

The Beck Depression Inventory II (BDI-II) was used to measure depressed mood among participants.Citation38 This tool has a good internal scale reliability for community-dwelling adults (Cronbach’s alpha =0.86–0.92).Citation39 Scores of 1–10 indicate no depressed mood; scores of 11–16 indicate mild mood disturbances; 17–20 represent borderline clinical depressed mood; 21–30 represent moderate depressed mood; 31–40 indicate severe depressed mood; and scores of 41 or more indicate extreme depressed mood.

The Short Form-36 (SF-36) was used to measure general health status.Citation40 The SF-36 is a commonly used instrument that measures eight dimensions of health: physical functioning, physical role functioning, bodily pain, general health perceptions, vitality, social role functioning, emotional role functioning, and mental health.

Four questions on self-esteem were taken from the Self-Description Questionnaire III. These questions asked participants to give an answer of 1) “false,” 2) “mostly false,” 3) “sometimes true, sometimes false,” 4) “mostly true,” and 5) “true” to each statement.Citation41

During a medical screen, each participant had their blood pressure, blood sugar, and blood cholesterol levels tested. Individual fitness evaluations were also conducted, which included calculation of each participant’s BMI, waist-to-hip ratio, body fat percentage, and aerobic fitness.Citation42

Procedures

The Healthy Weights Initiative is a community-based weight loss program offering group-based sessions at the local YMCA (Young Men’s Christian Association), and offered free of charge to all participants. Each participant received programming for 12 consecutive weeks, which included five group exercise sessions per week (60 in total) led by an exercise therapist; one group dietary session per week (12 in total) led by a dietician; and one group cognitive-behavioral therapy session per week (12 in total) led by a registered psychologist. After completing the program, participants received one group-based exercise session per week for an additional 12 weeks to serve as maintenance therapy. The details of each section of the program are described elsewhere.Citation43

Each participant was asked to attend with a family member or friend who also had a BMI of at least 30. This social support individual, or “buddy,” was also asked to sign a social support contract, which acknowledges the participant’s physical activity and dietary goals, possible barriers to achieving those goals, solutions to overcoming those barriers, and how the buddy can help implement those solutions. Two other family members or friends also signed the social support contract. Each of these components is recommended by the Canadian Society for Exercise Physiology Physical Activity Training for Health guidelines.Citation42

At 12 weeks, identical outcome measures from baseline were obtained from those who completed the program. Those who quit the program were contacted by clinic staff to complete a follow-up BDI-II survey.

Analysis

Those who scored 11 or higher on the BDI-II were considered to have depressed mood. Mean scores (with 95% confidence intervals [CI]) and prevalence rates between those who completed the program and those who quit the program were compared at baseline and follow-up, and chi-squares (SPSS Version 23.0) were used to determine statistically significant differences.

Those who completed the program and who scored 11 or higher on the BDI-II at baseline were included in an additional analysis. Baseline and follow-up mean BDI-II scores were compared using a paired samples t-test. Further, the group was broken down into two categories: those who no longer had depressed mood at follow-up and those who did. These groups were then compared across demographics, comorbidities, prescription drug use, smoking status, program adherence, self-esteem, self-report health, and self-report mental health using cross-tabulations. Mean scores were compared with 95% confidence intervals reported (P<0.05) for physiological measures (including weight, body composition, BMI, blood glucose, blood cholesterol, and blood pressure), and SF-36 domain scores were also compared across the two groups.

After these initial cross-tabulations, binary logistic regression was used to determine the independent association between the outcome variable of depressed mood at 12 weeks and the potential explanatory variables. In the case where means were statistically significant, scores were grouped into exclusive binary categories. The unadjusted effect of each covariate was determined and then entered one step at a time based on changes in the −2log likelihood and the Wald test. The final results are presented as adjusted odds ratios with 95% CIs.Citation44

Results

Participant demographic and baseline information are presented in . Females, younger participants (<45 years of age), and single participants had significantly higher mean scores on the baseline BDI-II, where higher scores indicate more depressed mood. There were no significant differences in baseline mean scores across education level, employment, smoking status, and program completion or adherence ().

Table 1 Participant demographics and baseline information in the Healthy Weights Initiative, N=296

Table 2 Baseline BDI-II scores across demographics and program completion and adherence (lower scores indicate better mood), N=290

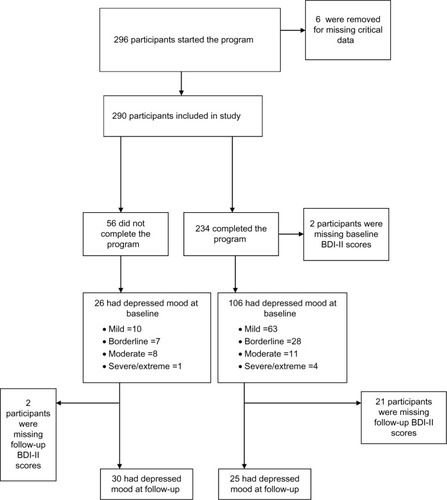

indicates the participant data used in this study. Those with missing data were removed from the analysis. The prevalence of depressed mood at baseline among those who completed the program (n=232) was 45.3% (27.2% had mild mood disturbances, 12.1% had borderline clinical depressed mood, 4.7% had moderate depressed mood, and 1.3% had severe or extreme depressed mood). The prevalence of depressed mood at baseline among those who quit the program (n=56) was 46.4% (17.9% had mild mood disturbances, 12.5% had borderline clinical depressed mood, 14.3% had moderate depressed mood, and 1.8% had severe or extreme depressed mood). The results are presented in . The higher scores among those who quit the program on the BDI-II are discussed in further detail in another paper.Citation43

Table 3 Comparing baseline and follow-up BDI-II scores between those who completed the program and those who quit (lower scores indicate better mood), N=290

The depressed mood prevalence at follow-up among those who completed the program decreased from 45.7% to 11.7% (9.9% had mild mood disturbances, 0.5% had borderline clinical depressed mood, and 1.4% had moderate depressed mood). In contrast, the depressed mood prevalence among those who did not complete the program increased to 55.6% at follow-up from 44.8% (14.8% had mild mood disturbances, 20.4% had borderline clinical depressed mood, and 20.4% had moderate depressed mood).

The 106 participants who were experiencing some level of depressed mood at baseline were included in an additional analysis. The sample was predominantly female (81.1%), and 18.9% were 55–64 years, 38.3% were 45–54 years, 30.2% were 35–44 years, 17.9% were 26–34 years, and 4.7% were 18–25 years. Two-thirds were married or in a common-law relationship, while the remaining 33% were not married. In regard to education, 15.1% completed university, 41.5% completed college, technical, or trade school, 35.8% completed high school, and 7.5% had less than high school education. Most were employed, with 67% working in nonprofessional fields and 17% working in professional fields. Baseline mean BDI-II score (16.2) differed significantly from the follow-up mean score (7.41), at P<0.001.

There were no significant differences among those who continued to have depressed mood from those who no longer had depressed mood at follow-up across sex, age, marital status, employment status, education level, or smoking status. Nor were there any significant differences in the number of comorbidities, number of prescription drugs, or health care utilization reported at baseline. Further, there were no significant differences between the two groups with regard to adhering to any segment of the program ().

Table 4 Subgroup with BDI-II scores of ≥11 at baseline (n=106)

Those who continued to have depressed mood after the program selected false or mostly false to the statement, “I like the way I look” at baseline significantly more than those who no longer reported depressed mood (P=0.001). There were no other differences in self-esteem variables or in self-report health or self-report mental health at baseline ().

Table 5 Subgroup with BDI-II scores of ≥11 at baseline (n=106)

Those who no longer reported depressed mood did score significantly better on the SF-36 pain (P=0.018) and general health domains (P=0.026) at baseline than those who continued to have depressed mood. Although those who were no longer depressed scored better on all remaining dimensions but one (role limitations due to emotional health), these were not significant. There were no statistically significant differences between those who continued to have depressed mood after the program and those who no longer had depressed mood on any physiological measure at baseline ().

After regression analysis (presented in ), only SF-36 general health domain score independently increased the risk of still having depressed mood at follow-up (odds ratio 3.39; 95% CI 1.18–9.72; P=0.023).

Table 6 Independent risk factors for having depressed mood at follow-up

Discussion

Although the Healthy Weights Initiative was designed as an obesity reduction program, the completion of the program is associated with a significant reduction in depressed mood. Among those who began the program with a BDI-II score of 11 or more (depressed mood), 67.9% no longer had depressed mood after 12 weeks. This is an important result, as even those with severe and extreme depressed mood improved. Depressed mood prevalence at baseline among those who quit the program was similar to those who completed the program (45.3% vs 46.4%), but after follow-up, those who quit the program reported an increased prevalence of depressed mood while those who completed the program showed a significant reduction. The prevalence of moderate to severe depressed mood at baseline was lower among those who completed the program than among those who quit. Among all participants, the prevalence of moderate to severe depressed mood was 8.3%, which is comparable to previous studies that used DSM-III criteria to diagnose depression.Citation26,Citation27

Those whose depressed mood improved at the end of the program responded with “sometimes true, sometimes false” more often to the statement “I like the way I look” at baseline than those who had depressed mood at the end of the program (96.9% vs 3.1%). Although not a necessarily positive answer, it suggests that those who no longer had depressed mood may self-evaluate their body image on a day-to-day basis, rather than having an overall negative outlook. This may be indicative for self-compassion, an alternative conceptualization of healthy attitude toward self, and an attribute theoretically protective against depression.Citation45

Those who no longer had depressed mood at follow-up had higher baseline scores on the SF-36 for pain, and therefore, more room to improve their pain. Pain has long been linked to depression.Citation46 A longitudinal study of 500 primary care patients over 1 year found that pain was a strong predictor of depression severity, but depression severity was also a strong predictor of subsequent pain.Citation47 Chronic pain is relatively common in Canadian population (18.9% in 2011),Citation48 and especially common among those with obesity.Citation49 One systematic review found obesity to be associated with pain from fibromyalgia, headaches, upper and lower extremity pain, and low back pain; the review further supports that weight loss can improve a wide variety of body pain related to obesity.Citation49

Further, those who no longer had depressed mood at follow-up had higher baseline scores on the SF-36 dimension of general health. This domain covers self-report health, expectations about future health, and comparing health to others. Having a lower baseline score on this domain independently increased the risk of having depressed mood at follow-up by 239%, suggesting those with worse self-perception of their health are harder to treat with regard to depressed mood. A study published in the Lancet on comorbid depression and chronic disease from 60 countries found that after controlling for socioeconomic factors and health conditions, depression was the strongest predictor of worsening health compared to arthritis, asthma, diabetes, and angina.Citation50 Given that 69.8% of the baseline depressed mood sample reported one or more comorbidities, this is important to consider when treating comorbid obesity.

Depressed mood is a central symptom of clinical depression and should be investigated and addressed promptly by care providers. Having a chronic condition, such as obesity, is significantly associated with having depression,Citation51 and as many as 74% of those who have depression do not seek treatment.Citation52 Adherence rates for medical treatment of depression are also notoriously poor. One study found that 45.9% of Canadian patients who are prescribed antidepressants quit taking their medication within 1 year.Citation53 Given that certain types of antidepressants may actually contribute to weight problems, these may not be a suitable treatment method for those who are already obese.

Failing to adequately acknowledge and treat depression is not only detrimental to the health of the individual but also expensive. In a study published by the Centre for Addiction and Mental Health, depression costs the Canadian economy $51 billion per year, with a majority due to lost productivity and absence from work. For example, when a worker takes leave from work due to depression, the average cost to an employer is $18,000.Citation54

The cognitive-behavioral therapy sessions offered in the program are important in addressing mental health, but the diet sessions and the exercise sessions, as well as losing weight itself, also play a role in positively impacting mood. For example, a study published in the American Journal of Psychiatry found that a “Western” diet was associated with poorer mental and physical health among women than “traditional” dietary patterns of high vegetable, fruit, meat, fish, and whole grains.Citation55

Exercise as a treatment for depression has received more research attention, but the quality of research appears to be low. In a 2013 review by the Cochrane Collaboration, a moderate effect was found for exercise in the treatment of depression when reviewing robust randomized controlled trials.Citation35 The authors concluded there is still a need for studies on the independent effect of exercise on depression. A systematic review of exercise interventions used as a method to manage depression published in the British Medical Journal came to a similar conclusion.Citation56 However, studies included in both reviews did not look at the impact of exercise on depression in an obese population.

Here, we reviewed the impact of a comprehensive intervention that included five exercise sessions a week on depressed mood in obese adults. Markowitz et alCitation29 suggest that overlap in treatment modalities for depression and obesity may be particularly effective, due to treating either condition will address improvements in life functioning and stress management. Challenges can occur in adherence, but the Healthy Weights Initiative has social support structures in place to improve adherence.

Clinical Implications

Depressed mood in obesity may be treated with an obesity-reduction program that includes exercise, cognitive behavioural therapy, and diet education. Depressed mood is strongly tied to general health and should be addressed by health care professionals among those suffering from obesity.

Limitations

Those who did not complete the program were all contacted between 6 months and 12 months after anticipated program completion. Further, the long-term (1 year) results of the study are not yet available. It is possible that adherence to weight loss practices promoted in the program may change, and therefore, the physical and mental health outcomes associated with the program may also change.

Conclusion

The Healthy Weights Initiative uses evidence-based practices, is comprehensive in its targeting of unhealthy weight behaviors, is community based, and promotes strong social support. Although designed as an obesity reduction program, there are benefits to mental health and depressed mood. Given the sometimes poor treatment outcomes with medical therapy,Citation57,Citation58 low adherence rates,Citation51 and the multiple pathways between obesity and depression, treating depressed mood through a community-based, weight-loss program based on evidence may be a superior alternative to medical treatment.

Acknowledgments

Special thanks to Alliance Wellness and Rehabilitation and to the Moose Jaw YMCA for administering the program and collecting the data. Funding was obtained from the Public Health Agency of Canada (1516-HQ-000036). The views expressed herein do not necessarily represent the views of the Public Health Agency of Canada. The authors have reviewed and agreed with the content of this manuscript.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- KumanyikaSJefferyRWMorabiaARitenbaugCAntipatisVJPublic health approaches to the prevention of obesity (PAHPO) working group of the international obesity task force (IOTF)Int J Obesity200226425436

- TremblayMSWillmsJDIs the Canadian childhood obesity epidemic related to physical inactivity?Int J Obesity20032711001105

- CrespoCJSmitETroianoPBartlettSJMaceraCAAndersenRETelevision watching, energy intake, and obesity in US childrenArch Ped Adoles Med2001155360365

- JanssenIKatzmarzykPTBoyceWFKingMAPickettWOverweight and obesity in Canadian adolescents and their associations with dietary habits and physical activity patternsJ Adolesc Health20043536036715488429

- MozaffarianDHaoTRimmEBWillettWCHuFBChanges in diet and lifestyle and long-term weight gain in women and menN Eng J Med201136423922404

- ChangVWLauderdaleDSIncome disparities in body mass index and obesity in the United States, 1971–2002Arch Int Med20051652122212816217002

- TwellsLKGregiryDMReddiganJMidoziWKCurrent and predicted prevalence of obesity in Canada: a trend analysisCan Med Assoc J20142351826

- MustASpadanoJCoakleyEHFieldAEColditzGDietzWHThe disease burden associated with overweight and obesityJAMA1999282161523152910546691

- MansonJEStampferMJColditzGAA prospective study of obesity and risk of coronary heart disease in womenN Eng J Med199032213882889

- De KoningLMerchantATPogueJAnandSSWaist circumference and waist-to-hip ratio as predictors of cardiovascular events: meta-regression analysis of prospective studiesEur Heart J200728785085617403720

- AndersonJWKendallCWCJenkinsDJAImportance of weight management in type 2 diabetes: review with meta-analysis of clinical studiesJ Amer C Nutr2003225331

- CalleEERodriguezCWalker-ThurmondKThunMJOverweight, obesity, and mortality from cancer in a prospectively studied cohort of U.S. adultsN Engl J Med2003348171625163812711737

- LigibelJAAlfanoCMCourneyaKSAmerican society of clinical oncology position statement on obesity and cancerJ Clin Oncol201432313568357425273035

- ReevesGKPirieKBeralVMillion Women Study CollaborationCancer incidence and mortality in relation to body mass index in the Million Women Study: cohort studyBr Med J20073357630113417986716

- Van DamRMLiTSpiegelmanDFrancoOHHuFBCombined impact of lifestyle factors on mortality: prospective cohort study in US womenBr Med J2008337a144018796495

- AdamsKFScatzkinAHarrisTBOverweight, obesity and mortality in a large prospective cohort of persons 50 to 71 years oldN Eng J Med20062558763778

- CalleEEThunMJPetrelliJMRodriguezCHeathCWJrBody mass index and mortality in a prospective cohort of US adultsN Eng J Med19993411510971105

- FlegalKMGraubardBIWiliamsonDFGailMHExcess deaths associated with underweight, overweight and obesityJAMA2005293151861186715840860

- FontaineKRReddenDTWangCWestfallAOAllisonDBYears of life lost due to obesityJAMA2003289218719312517229

- OlshanskySJPassaroDJHershowRCA potential decline in life expectancy in the United States in the 21st centuryN Eng J Med20101701512931301

- JacobsEJNewtonCCWangYWaist circumference and all-cause mortality in a large US cohortArch Intern Med2010170151293130120696950

- SimonGEVon KorffMSaundersKAssociation between obesity and psychiatric disorders in the US adult populationArch Gen Psychaitry200663824830

- MauroMTaylorVWhartonSSharmaAMBarriers to obesity treatmentEurop J Intern Med200819173780

- LindeJAJefferyRWLevyRLBinge eating disorder, weight control self-efficacy, and depression in overweight men and womenInt J Obes Relat Metab Disord20042841842514724662

- McGuireMTWingRRKlemMLLangWHillJOWhat predicts weight regain in a group of successful weight losers?J Consult Clin Psychol19996717718510224727

- OnyikeCUCrusRMLeeHBLyketsosCGEatonWWIs obesity associated with major depression? Results from the Third National Health and Nutrition Examination SurveyAm J Epidemiol20031581139114714652298

- RobertsREKaplanGAShenaSJStrawbridgeWJAre the obese at greater risk for depression?Am J Epidemiol2000152216317010909953

- PrattLABrodyDJDepression and obesity in the US adult household population 2005–2010NCHS Data Brief20141671825321386

- MarkowitzSFriedmanMAArentSMUnderstanding the relation between obesity and depression: causal mechanisms and implications for treatmentClin Psychol Sci Prac200815120

- OuwensMAvan StrienTvan LeeuweJFJPossible pathways between depression, emotional and external eating. A structural equation modelAppetite200953224524819505515

- GluckMEGeliebterASatovTNight eating syndrome is associated with depression, low self-esteem, reduced daytime hunger, and less weight loss in obese outpatientsObes Res20019426426711331430

- SchwartzTLNihalaniNJindalSVirkSJonesNPsychiatric medication-induced obesity: a reviewObes Rev2004511512115086865

- LuppinoFSde WitLMBouvyPFOverweight, obesity and depression: a systematic review and meta-analysis of longitudinal studiesJAMA Psychiatry2010673220229

- DixonJBDixonMO’BrienPEDepression in association with severe obesity changes with weight lossArch Intern Med20031632058206514504119

- CooneyGMDwanKGreigCAExercise for depressionCochrane Database Syst Rev20139CD00436610.1002/14651858.CD004366.pub624026850

- KushnarRFRyanDHAssessment and lifestyle management of patients with obesity: clinical recommendations from systematic reviewsJAMA2014312994395225182103

- Statistics Canada [homepage on the Internet]Canadian Community Health SurveyStatistics Canada2013 Available from: www.12statcan.gc.caAccessed December 10, 2014

- BeckATSteerRABrownGKManual for the Beck Depression Inventory-IISan Antonio, TXPsychological Corporation1996

- SegalDLCoolidgeFLCahillBSO’RileyAAPsychometric properties of the Beck Depression Inventory-II (BDI-II) among community-dwelling older adultsBehav Modif200832132018096969

- WareJEKosinskiMKellerSDSF-36 Physical and Mental Health Summary Scales: A Users’ ManualBoston, MAThe Health Institute1994

- MarshHWO’NeillRSelf Description Questionnaire III: the construct validity of multidimensional self-concept ratings by late adolescentsJ Ed Meausurement1984212153174

- Canadian Society for Exercise PhysiologyPhysical Activity Training for Health – Resource ManualOttawa, ON2013

- LemstraMRogersMThe importance of community consultation and social support in adhering to an obesity reduction program: results from the healthy weights initiativePatient Pref Adherence2015914701483

- RothmanKJGreenlandSModern Epidemiology2nd edPhiladelphia, PALippincott Williams and Wilkins1998

- NeffKSelf-compassion: an alternative conceptualization of a healthy attitude toward oneselfSelf Identity2003285101

- FishbainDCutlerRHubertRRosomoffRSChronic pain-associated depression: antecedent or consequence of chronic pain? A reviewClin J Pain19971321161379186019

- KroenkeKWuJBairMJKrebsEEDamushTMTuWReciprocal relationship between pain and depression: a 12-month longitudinal analysis in primary careJ Pain201112996497321680251

- SchopflocherDTenzerPJoveyRThe prevalence of chronic pain in CanadaPain Res Manage2011166445450

- NarouzeSSouzdalnitskiDObesity and chronic pain: systematic review of prevalence and implications for pain practiceReg Anesth Pain Med20154029111125650632

- MoussaviSChatterjiSVerdesETandonAPatelVUstunBDepression, chronic diseases, and decrements in health: results from the World Health SurveysLancet2007370959085185817826170

- PattenSBWangJLWilliamsJVDescriptive epidemiology of major depression in CanadaCan J Psychiatry2006512849016989107

- Statistics CanadaDepression: an undertreated disorder?Health Rep199784 Available from: http://www5.statcan.gc.ca/olc-cel/olc.action?ObjId=82-003-X19960043021&ObjType=47&lang=enAccessed October 22, 2015

- BullochAGPattenSBNon-adherence to psychotropic medications in the general populationSoc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol2010451475619347238

- AmbaDDepression costs Canada $51 billion per yearPostmedia News2012 Available from: http://www.canada.com/business/Depression+costs+Canada+billion+year/6002202/story.htmlAccessed November 6, 2013

- JackaFNPascoJAMykletunAAssociation of Western and Traditional diets with depression and anxiety in womenAmer J Psychiatry2010167330531120048020

- LawlorDAHopkerSWThe effectiveness of exercise as an intervention in the management of depression: systematic review and meta- regression analysis of randomised controlled trialsBMJ200132276311282860

- MoncrieffJWesselySHardyRActive placebos versus antidepressants for depressionCochrane Database Syst Rev20041CD00301214974002

- KirschIMooreTJScoboriaAThe Emperor’s new drugs: an analysis of antidepressant medication data submitted to the US Food and Drug AdministrationPrev Treatment2002523111