Abstract

Introduction

Work ability constitutes one of the most studied well-being indicators related to work. Past research highlighted the relationship with work-related resources and demands, and personal resources. However, no studies highlight the role of collective and self-efficacy beliefs in sustaining work ability.

Purpose

The purpose of this study was to examine whether and by which mechanism work ability is linked with individual and collective efficacies in a sample of primary and middle school teachers.

Materials and methods

Using a dataset consisting of 415 primary and middle school Italian teachers, the analysis tested for the mediating role of self-efficacy between collective efficacy and work ability.

Results

Mediational analysis highlights that teachers’ self-efficacy totally mediates the relationship between collective efficacy and perceived work ability.

Conclusion

Results of this study enhance the theoretical knowledge and empirical evidence regarding the link between teachers’ collective efficacy and self-efficacy, giving further emphasis to the concept of collective efficacy in school contexts. Moreover, the results contribute to the study of well-being in the teaching profession, highlighting a process that sustains and promotes levels of work ability through both collective and personal resources.

Introduction

It is well established that teaching is a stressful occupationCitation1,Citation2 due to societal, organizational, and interpersonal challenges that affect this profession. Most research in occupational health psychology investigated the negative aspects in the teaching profession that could affect health and well-being at work or that may foster malaise, such as burnout.Citation3 On the other hand, fewer studies focused on factors that could sustain teachers’ well-being at work. One of the most studied constructs in well-being literature is work ability which, according to Tuomi et al,Citation4 describes the physical and intellectual resources on which workers rely to meet the demands posed by their work.

According to Tengland,Citation5 work ability refers to the ability to carry out the work, which encompasses health-required status, occupational virtues, and competence for managing job tasks, and it is measured through the Work Ability Index (WAI).Citation6 This tool consists of seven subscales regarding the subjective perception about the actual work ability (physical and mental resources) compared with the lifetime best, a subjective prognosis of work ability and mental resources, the work impairment, the number of diseases, and the absence from work due to disease. In this vein, work ability is a measure that is based on both burden of disease (given by number of diseases and the days of absence from work) and the individual perception of work ability. In this study, as previously done by other studies,Citation7,Citation8 we are interested to disentangle the health status from perceived work ability, which could be conceptualized as a subjective indicator of well-being.

As emerged from a systematic review,Citation9 work ability has been mainly investigated in “aging” or “differences in ages” perspectives in relation to sociodemographic or life-style factors, work-related resources, and demands. In this perspective, prior research has outlined how physical and mental work demands (e.g., Ilmarinen et alCitation10) on the one hand, and autonomy, supervisor support, and developmental opportunities on the other hand, constitute a pool of work-related factors that impact mainly on work ability.Citation7,Citation11

This trend is also reflected in studies focused on work ability in the teaching profession.Citation8,Citation12–Citation16 Regarding specifically the Italian educational context, evidence suggests that work ability decreases as a function of ageCitation17 and that job resources differently impact on work ability across age cohorts.Citation18 Otherwise, very few studies have analyzed the impact of psychological resources on work ability. Like job resources, psychological resources have a central role in dealing with stress as they contribute to inhibit dysfunctional responses to stressful situations.Citation19 In this vein, as work ability represents a subjective indicator of well-being, it could be stated that psychological resources positively affect work ability.

Among research studies that first highlighted the role of psychological resources in relation to work ability, Airila et al,Citation20 within the framework of the Job Demand-Resource model,Citation21 evidenced that self-esteem is positively related with work ability via work engagement, whereas Sjogren-Ronka et alCitation22 found a direct and positive relationship between self-concept and work ability. Moreover, the study by McGonagle et alCitation19 outlined that sense of control, which constitutes a relatively general and stable individual perception about one’s own control over internal states, behaviors, and the environment, is an important source in sustaining work ability levels.

Even if these latter studies have outlined that various personal resources may play a central role in the promotion of work ability in different working populations, it is important to note that to date no scholars have considered the role exerted by self-efficacy. Self-efficacy is a personal resource that refers to a pattern of future-oriented beliefs about one’s own capabilities in relation to specific tasks, and may determine how context-specific environmental opportunities or impediments are perceived. Moreover, the concept of self-efficacy differs from self-esteem and self-confidence which on the other hand represent positive self-evaluations of one’s worth, significance, and ability as a person.Citation23 Finally, differently from sense of control, self-efficacy is conceptualized as a context-specific and malleable belief about individual capabilities in facing external conditions. Furthermore, the differentiation between self-efficacy and sense of control has been clearly shown even within the teacher efficacy literatureCitation24 that developed measures based on Bandura’sCitation25 conceptualization of self-efficacy.Citation26

As suggested by Bandura,Citation25 teachers with low levels of self-efficacy tend to perceive their work environment as full of dangers or to emphasize the negative consequences of possible threats. These features may in turn contribute to undermine work ability. Moreover, regarding contextual resources, no studies took into account the role exerted by collective efficacy on work ability. As it will be further outlined, collective efficacy represents one of the main sources of self-efficacy.Citation27 For this reason, we aim at examining the relationships between collective efficacy, self-efficacy, and work ability. In this view, understanding whether and by which mechanism work ability is linked with individual and collective efficacies may represent a powerful starting point to improve current knowledge regarding how to sustain work ability in the teaching profession.

Teachers’ self-efficacy

The construct of self-efficacy in reference to the teaching profession has raised growing attention since the earliest studies of the RAND Corporation,Citation28 which have highlighted how it is linked to teachers’ professional behaviors and students’ learning outcomes.Citation29 Self-efficacy represents the individual teachers’ beliefs in their own abilities to “plan, organize, and carry out activities required to attain given educational goals,” (p. 612).Citation26 Grounded into the human agency perspective,Citation30,Citation31 the concept of self-efficacy refers to a pattern of future-oriented beliefs that may influence not only behaviors and actions but also emotions, thoughts, and feelings, affecting the persistence and resilience in demanding situations. Stress or feelings of depression may be the result of self-inefficacy beliefs adopted in coping with environmental strains.Citation25

As stated by Zee and Koomen,Citation32 most studies on teachers’ self-efficacy were developed in order to detect its effect on students’ level outcomes or on academic adjustment,Citation33,Citation34 identifying as mediators in these relationships the ability to deal with instructional problems,Citation35,Citation36 to manage interpersonal dynamics with students,Citation37,Citation38 or to organize classroom processes.Citation39,Citation40

Although scholars’ attention has been mainly paid to the relationship between teachers’ self-efficacy and students’ level outcomes, some studies highlighted how teachers’ self-efficacy is a central personal resource to understand psychological well-being. Particularly, studies have pointed out that a high level of self-efficacy may reduce burnout levels,Citation41–Citation45 and enhance job satisfactionCitation46 and commitment.Citation47,Citation48

Given its importance in sustaining well-being, it is also interesting to highlight possible factors capable of fostering self-efficacy. Moreover, a series of studies showed how environmental stressors in the educational context prevent teachers from sustaining their self-efficacy beliefs,Citation49–Citation51 while others investigated the sources that enhance self-efficacy.Citation52,Citation53 A concept that may be considered as a resource of self-efficacy is collective efficacy.

Teachers’ collective efficacy

In organizational contexts, such as the schools, the construct of efficacy might be investigated not only as a self-referent perception about own capabilities, but also as an emergent property of the (social) system as a whole, called “collective efficacy” (p. 467).Citation25 Specifically referred to the educational context, it represents the teachers’ beliefs that the school as a whole can implement and organize courses of actions affecting students and their levels of attainments.Citation29 Even if it is an understudied construct, if compared with its “self ” counterpart, collective efficacy is a powerful parameter to understand the quality of school life, also in terms of teachers’ well-being. This tenet stems primarily from the fact that instructional reforms in Italy, since the late 1990s, have increasingly empowered single schools. In this reformed context, teachers are encouraged to work in a team, to share their goals and activities, thus grounding on these conjoint experiences the perception of their collective efficacy.Citation54 Moreover, since the seminal work of Goddard et alCitation55 on the predictive role of collective efficacy on students’ academic achievement, many studies have been developed, which have extended the study to the relationships of collective efficacy with school climate and teachers’ well-being.Citation56–Citation58 Moreover, as the collective efficacy is an emerging group-level property of shared actions separated and not reducible to the sum of self-efficacy beliefs,Citation59 it is possible to expect the existence of a relationship with self-efficacy as well, as emerged from different school–organizational studies.Citation47,Citation60–Citation62

Theoretically speaking, it is possible to state that collective efficacy influences levels of self-efficacy.Citation63 In line with Coleman’s assumption on the role of social norms in affecting group behavior,Citation64 goals and actions shared within a school act as source of normative pressure to which single teachers tend to conform. Moreover, this process is consistent with what has been proposed by Bandura’s Social Cognitive TheoryCitation65: the main sources of influence in the development of efficacy beliefs are social persuasion and mastery experience, which, at the school level, act as normative pressures. The high expectations set in a school with perceived high collective efficacy may encourage teachers to foster their persistence in front of the challenges posed by the school itself. Even if it is possible that comparison with a high efficacy environment could threaten some teachers’ self-efficacy, past studies have highlighted that social comparison is more important for the development of self-concept than that of self-efficacy.Citation66,Citation67 Conversely, a teacher’s self-efficacy may decrease when, at faculty level, there are low expectations about future goal attainment, and colleagues or supervisors could not sustain the resilience, due to past failures, in front of demanding situations. As outlined from Skaalvik and Skaalvik,Citation45 collective efficacy seems to be mostly correlated with supervisor’s support, which is a source of the norms, values, and goals shared among the teachers of a faculty. In line with the above, Luthans et alCitation68 asserted that a resourceful work environment, such as the one with high collective efficacy, sustains the employees’ “psychological capital” (i.e., optimism, hope, resiliency, and efficacy development), thus activating personal resources that could in turn enhance psychological and organizational well-being.

From an empirical point of view, Goddard and GoddardCitation27 examined this predictive role demonstrating how collective efficacy was the most powerful antecedent of self-efficacy over the effect of other school-level characteristics, such as socioeconomic status (SES), proportion minority, school size, and past achievement. Moreover, Lev and KoslowskyCitation69 supported the same statement, highlighting that the relationship between teachers’ collective and self efficacies is moderated by occupational level (managerial vs. non-managerial). Subsequently, this path has been extended in the study of teachers’ level outcomes, primarily in the prediction of burnout and job satisfaction. Skaalvik and SkaalvikCitation26 demonstrated that self-efficacy completely mediates the effect of collective efficacy on teachers’ burnout, highlighting how this contextual resource lessens burnout symptoms through the improvement of self-efficacy.

Despite the theoretical groundCitation63 which suggests the role played by collective efficacy as an antecedent of teachers’ self-efficacy, the empirical evidence of the mediating role exerted by teachers’ self-efficacy between teachers’ collective efficacy and teachers’ well-being is, however, still lacking investigation.

Even if in the literature there are many studies that support the significance of the positive association between teachers’ self-efficacy and some indicators of well-being (e.g., burnout, job satisfaction, and commitment), no evidence exists about its relationship with work ability. Finally, no studies examined the role exerted by collective efficacy in predicting work ability either directly or indirectly via self-efficacy.

Based on the theoretical and empirical background, this study has the aim to investigate a model of well-being at work, positing that teachers’ collective efficacy acts as an environmental school resource in fostering teachers’ self-efficacy beliefs which in turn enhance work ability.

The study hypotheses are:

H1: Teachers’ collective efficacy positively relates to teachers’ self-efficacy and work ability.

H2: Teachers’ self-efficacy positively relates to perceived work ability.

H3: Teachers’ self-efficacy mediates the relationship between teachers’ collective efficacy and work ability.

Materials and methods

Design and ethical considerations

A cross-sectional design was used in order to collect data by means of a self-reported questionnaire. Data collection was conducted in a research program aimed at assessing the quality of teachers’ working life. Before data collection, a series of meetings was conducted with the aim of sharing the objectives and the time plan of the research with both school administrators and teachers’ representatives, who evaluated and authorized the use of data collection for scientific purposes.

Participants volunteered for the research without receiving any reward, signed the informed consent, and agreed to anonymously complete the questionnaire. The research conforms to the Declaration of Helsinki of 1995 (as revised in Edinburgh 2000), and all ethical guidelines were followed as required for conducting human research, including adherence to legal requirements of the study country. An additional ethical approval was not required since there was no treatment, including medical, invasive diagnostics or procedures causing psychological or social discomfort for the participants.

Data collection

After explaining the project’s aims, a self-reported questionnaire was administered from January to March 2016. Teachers at their own convenience returned the completed questionnaire anonymously in sealed boxes. Overall, the response rate was 33.93% (415 of the 1223 questionnaire were returned and considered valid for the analysis).

The majority of the participants were women (331, 79.8%). The sample has a mean age of 45.11 years (SD=9.06); min=23 years; max=63 years. Based on the grade level, the sample consisted of 232 primary school teachers (55.9%) and 183 (44.1%) middle school teachers.

Instrumentation

Teachers’ Self-Efficacy was measured with the Perceived Personal Efficacy Scale in the school context.Citation70 This one-dimensional scale consisted of 12 items (seven-point Likert scale ranging from 1=totally disagree to 7=totally agree) aimed at capturing the teachers’ self-efficacy in attaining educational and learning outcomes (e.g., “I can successfully cope with the difficulties in gaining learning attainments”).

Teachers’ Collective Efficacy was measured with the Perceived Collective Efficacy in school context.Citation70 This one-dimensional scale consisted of nine items (seven-point Likert scale ranging from 1=totally disagree to 7=totally agree). In line with the theoretical ground, collective efficacy does not derive from the sum of individual self-efficacy beliefs, but it captures otherwise the teachers’ beliefs about the school’s (as a whole) ability to successfully cope with critical situations (e.g., “Our school is able to fully achieve the objectives of school autonomy reforms”).

Work ability

The authors employed a modified version of the Work Ability IndexCitation6 specifically aimed at assessing perceived work ability (WAI perceived), as suggested by McGonagle et al.Citation7,Citation71 It contained five items: 1) current work ability compared with lifetime best (range of the score 1–10); 2) work ability in relation to mental and physical demands (range of the score 2–10); 3) estimated work impairment due to diseases (range of the score 1–6); 4) self-prognosis of work ability for the next 2 years (range of the score 1–4 or 7); and 5) mental resources (range of the score 1–4).

Control variables

Literature findings highlight that age, gender, grade level (primary vs. middle school teachers), perceived health status, and psychological well-being (i.e., psychological exhaustion) may represent potential confounders in the relationships between efficacy and work ability.Citation7–Citation10 In order to collect data on psychological well-being at work, we measured psychological exhaustion using the Italian version of the Spanish Burnout InventoryCitation62,Citation73 consisting of four items (five-point Likert scale ranging from 0=Never to 4=Every Day; e.g., “I feel emotionally exhausted”). Perceived health status was measured with a single item: “How do you generally evaluate your own health status?” (Four-point scale ranging from: 1=excellent to 4=very poor). Low scores indicate positive evaluation of health; conversely, higher scores indicate poorer health status.

Statistical analyses

Statistical analyses were carried out using SPSS Package version 23. Means, standard deviation, and internal consistency of each variable under study were performed (). For each measure, items were summed and used for subsequent analyses.

Table 1 Means, standard deviations, and Cronbach’s alphas for each subscale

Preacher and HayesCitation74 analytical approach was used in order to test the mediating role played by teachers’ self-efficacy in the relationship between collective efficacy and work ability. This approach allowed us to test the indirect effect of a hypothesized antecedent variable on the outcome variable through a mediator. Moreover, through the evaluation of the total effect model (i.e., the effect of the antecedent variable on the outcome when the mediator is not included in the model), it evaluates if there is a total or a partial mediational effect. Furthermore, the bootstrap sampling procedure was used to generate a 95% CI around the indirect effect to test for its significance. When 95% CI did not include zero, the indirect effect is significant. Bootstrap confidence intervals were constructed using 5000 samples.

Results

Descriptive statistics and correlations

summarized means, standard deviations, and Cronbach’s alpha for all the studied variables.

Pearson’s correlations () indicate that all the studied variables are significantly associated in the expected direction. As emerged, perceived work ability is positively and moderately correlated with both teachers’ self and collective efficacies; furthermore, concerning the control variables, perceived work ability is negatively correlated with psychological exhaustion, perceived health status, and age. Finally, gender and grade level are not significantly correlated with perceived work ability; consequently, they have not been inserted into the mediational analysis.

Table 2 Pearson’s correlations between all the studied variables

Mediational analysis

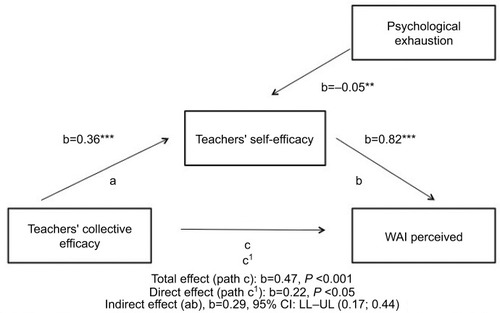

Mediational analysis was then carried out in order to find out all the direct effects within the model and the indirect effect of collective efficacy on perceived work ability (controlling for age, perceived health status, and psychological exhaustion). represents the model of relationships between teachers’ collective efficacy and self-efficacy beliefs and work ability, reporting unstandardized coefficients.

Figure 1 Model of relationships between teachers’ collective efficacy and self-efficacy beliefs and work ability.

Abbreviations: LL, lower level; UL, upper level; WAI, work ability index.

The estimates of path coefficients highlight that, on one hand, the total effect of collective efficacy on work ability is positive and significant on perceived work ability (path c, ; b=0.47; p<0.001). Among the control variables, age (b=−0.10; p<0.001), perceived health status (b=−0.74; p<0.001), and psychological exhaustion (b=−0.33; p<0.001) were significantly associated with perceived work ability and in the expected direction. On the other hand, teachers’ collective efficacy positively affects teachers’ self-efficacy (b=0.36; p<0.001; path a) and, among the control variables, only psychological exhaustion significantly relates with self-efficacy, exerting a negative effect (b=−0.05; p<0.01). These findings support H1.

Moreover, teachers’ self-efficacy significantly and positively impacts on perceived work ability (b=0.82, p<0.001; path b), supporting H2. Finally, consistent with our hypothesis concerning the indirect effect (a×b; i.e., the relationship between collective efficacy and work ability through the relationship with self-efficacy), the results evidence that self-efficacy significantly mediates the relationship between collective efficacy and perceived work ability (b=0.29; 95% CI [LL–UL]: 0.17–0.44). These findings support H3, and, following Baron and Kenny,Citation75 there is a full mediational effect of self-efficacy between collective efficacy and perceived work ability. In fact, as emerged from the analyses, the direct effect of teachers’ collective efficacy is not significant (b=0.22, p>0.05, ; path c1). Among the control variables, age (b=−0.10; p<0.001), perceived health status (b=−0.70; p<0.001), and psychological exhaustion (b=−0.30; p<0.001) were significantly associated with perceived work ability and in the expected direction.

Since our data were cross-sectional, we also tested the hypothesized model against an alternative model that links teachers’ self-efficacy with work ability via collective efficacy. Results showed that this alternative model was not supported, as the indirect effect was not found to be significant (b=0.06; 95% CI: −0.037, 0.045). Therefore, additional support to our hypothesis on the mediating role of teachers’ self-efficacy was found.

Discussion

This study gives important insights regarding how to sustain work ability in the teaching profession. Taken together, the results that emerged confirm the hypothesized model () in which perceived work ability of teachers constitutes the outcome of an efficacy process which starts from collective efficacy passing through self-efficacy beliefs.

Despite the emerging interest paid to collective efficacy in educational contexts, this is to date an understudied construct, specifically in the realm of teachers’ well-being literature. This study has outlined, confirming previous theoretical assumptionsCitation25,Citation63 and empirical findings,Citation26,Citation27 that collective efficacy in the teaching profession is related to self-efficacy. Despite the absence of longitudinal data not permitting to define a causality process between the variables under study, it is possible to note that collective efficacy beliefs act as powerful contextual resources in sustaining self-efficacy. An explanation of that relationship could be found within the Social Cognitive Theory,Citation65 which has outlined that the main sources of self-efficacy are mastery experience and social/verbal persuasion. Translated within the school context, these sources – that is, mastery faculty experience and instructions given by colleagues and superiors – could enhance and sustain efficacy beliefs in teachers. As BanduraCitation65 has explained, through these sources the school setting defines goals and attainments, leading teachers to gain the expectations set by the environment.

Moreover, as emerged from the analyses, even if collective efficacy positively impacts on the final outcome, it disappears after including self-efficacy into the model. This means that self-efficacy totally mediates the impact of collective efficacy on perceived work ability, thus representing a fundamental psychological resource able to sustain perceived work ability among teachers. In this vein, the results of this study improve what has previously emerged from past researchCitation19,Citation20,Citation22 which underscored the importance of other personal resources, such as self-esteem, self-concept, and sense of control to understand perceived work ability and how to sustain it. Otherwise, differently from the extant literature, the present study takes into consideration a context-specific and more malleable personal resource, that is, teachers’ self-efficacy. In this vein, our results give further insights regarding the role of personal resources in sustaining perceived work ability, as self-efficacy is more amenable to changes and improvements than more stable factors such as sense of control or self-esteem.

Conclusion

In the teaching profession, the possibility to maintain an adequate level of work ability, that is, the sum of mental and physical resources needed to manage the work tasksCitation10 in an ever-changing environment, is a central point given the social relevance of this profession and its role played in the students’ educational process. This study contributes to the work ability literature as it supports the importance to pay attention not only to sociodemographical or job-related features, but also to the personal features in promoting better levels of work ability. Through these results, we argue that supporting measures to work ability will take into account and assess the psychological resources, such as self-efficacy, on which the person can rely on.

Specifically, as self-efficacy affects the way of perceiving environmental opportunities or impediments, influencing goals, values, and behaviors, it is possible to state, in light of our results, that it could affect the way through which people evaluate their own ability at work: the more the teachers believe in their own capability, the more the resources will be devoted to gain professional tasks. This is of further importance, even for practical implications, because teachers’ self-efficacy is a context-specific personal resource to leverage within the educational work environment. In this vein, this study highlights that the relationship between self-efficacy and work ability is in turn sustained by collective efficacy, which has important implications at both theoretical and practical levels. On one hand, it highlights that the role of self-efficacy in sustaining well-being in organizations is better explained by considering at the same time the role of collective efficacy. This may be particularly true in the case in which the organization is a school: in this context working in teams and sharing goals represent key aspects to sustain the quality of the teaching process. Indeed, for teachers, gaining insights into their practices and understanding learning environment conditions seem to lessen the risk of work overload and difficulties in managing learning process.Citation76 Moreover, self and collective efficacies may allow teachers to provide students with significant learning experiences, thus stimulating students’ perception of self-efficacy.Citation77

Finally, on the practical side, with the aim to develop teachers’ self-efficacy and consequently work ability, school administrators have to favor those processes that enhance or maintain collective efficacy such as sharing goals, values, and past success collectively, favoring the school’s institutional commitment with other public or private institutions and with students’ families.

Limitations

The present study has some limitations. First of all, the cross-sectional design does not permit to evaluate causal relationships between the variables. Longitudinal studies would explore cross-lagged associations between the constructs, examining also cyclic relationships and the impact that work ability could have on self-efficacy.

Another limitation concerns the measurement of self-efficacy beliefs. Though we used a well-established instrument to measure teachers’ self-efficacy beliefs,Citation70 this one-dimensional instrument does not permit to take into account the variety of tasks and demanding situations which teachers have to face. Future studies, using multidimensional measurements, may highlight different patterns between various aspects of self-efficacy and work ability.

Concerning measurement properties, perceived WAI did not reach quite satisfactory levels of reliability. This issue represents another limitation of the study, as it could undermine the accuracy of measurement effects. Regarding this issue, most of the past studies that evaluated work ability in the teaching professionCitation13,Citation14 did not report levels of reliability for this measure, except for the study of Viotti et alCitation8 which reached adequate levels of reliability for perceived work ability in a sample of preschool teachers. Moreover, given the differences in measurement and sampling characteristics, future studies could shed more light on this issue, assessing perceived work ability in primary and middle school teachers to uncover comparable results.

Moreover, the sampling procedure was not randomized, and the sample is constituted of primary and middle Italian school teachers only. This implies that the results are not generalizable to other occupational sectors or also to other teachers’ grade level. Moreover, it is possible that these results could change as a function of the culture (individualistic vs. collectivistic),Citation78 especially regarding the relationship between collective and self-efficacy beliefs. Therefore, future studies could be implemented in order to detect possible cross-cultural differences.

Finally, as stated before, teachers’ work ability has been principally evaluated in studies concerning the aging workforce.Citation8,Citation12–Citation16 In this view, this model could be tested in older teachers’ samples aiming to highlight its applicability also in sustaining active aging processes and favoring work ability in elderly teachers.

Author contributions

All authors contributed toward data analysis, drafting and revising the paper and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Acknowledgments

This work received a financial contribution from “Acamedia” (https://www.acamedia.unito.it/), in partnership with Collegio Carlo Alberto, Turin, Italy.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- Lodolo D’OriaVPecori GiraldiFVitelloAVanoliCZeppegnoPFrigoliPBurnout e patologia psichiatrica negli insegnanti [Burnout and psychiatric pathology in teachers]2006MilanoStudio Getzemani Available from: http://www.edscuola.it/archivio/psicologia/burnout.pdfAccessed July, 16, 2017

- StoeberJRennertDPerfectionism in school teachers: relations with stress appraisals, coping styles, and burnoutAnxiety Stress Coping2008211375318027123

- KyriacouCTeacher stress. Directions for future researchEduc Rev20015312735

- TuomiKEskelinenLToikkanenJJarvinenEIlmarinenJKlockarsMWork load and individual factors affecting work ability among aging municipal employeesScand J Work Environ Health199117Suppl 11281341792526

- TenglandPAThe concept of work abilityJ Occup Rehabil201121227528521052807

- TuomiKIlmarinenJJahkolaAKatajarinneLTulkkiAWork Ability Index2nd edHelsinkiFinnish Institute of Occupational Health1998

- McGonagleAKBarnes-FarrellJLDi MiliaLDemands, resources, and work ability: a cross-national examination of health care workersEur J Work Organ Psychol2014236830846

- ViottiSGuidettiGLoeraBMartiniMSottimanoIConversoDStress, work ability, and an aging workforce: a study among women aged 50 and overInt J Stress Manag201624Suppl 198121

- Van den BergTIJEldersLAMZwartBCHBurdorfAThe effects of work-related and individual factors on the work ability index: a systematic reviewOccup Environ Med200966421122019017690

- IlmarinenJTuomiKSeitsamoJNew dimensions of work abilityCostaGGoedhartWGAIlmarinenIProceedings of the 2nd International Symposium on Work Ability2004 Oct 18–20Verona, ITInternational Congress SeriesElsevier2005128037

- Estryn-BeharMKreutzGLe NezetOPromotion of work ability among French health care workers–value of the Work Ability IndexCostaGGoedhartWGAIlmarinenIProceedings of the 2nd International Symposium on Work Ability2004 Oct 18–20Verona, ITInternational Congress SeriesElsevier200512807378

- HakanenJJBakkerABSchaufeliWBBurnout and work engagement among teachersJ Sch Psychol2006436495513

- MarquezeECVoltzGPBorgesFNSMorenoCRCA 2-year follow up study of work ability among college educatorsAppl Ergon200839564064518377866

- KinnuenUParkattiTRaskuAOccupational wellbeing among ageing teachers in FinlandScand J Educ Res1999383–4315332

- SeibtRSpitzerSBlankMScheuchKPredictors of work ability in occupations with psychological stressJ Public Health2009171918

- Vedovato GiovanelliTMonteiroIHealth conditions and factors related to the work ability of teachersInd Health201452212112824429517

- ConversoDViottiSSottimanoICascioVGuidettiGCapacità lavorativa, salute psico-fisica, burnout ed età, tra insegnanti d’infanzia ed educatori di asilo nido: uno studio trasversale [Work ability, psycho-physical health, burnout, and age among nursery school and kindergarten teachers: a cross-sectional study]Med Lav20151069110825744310

- SottimanoIViottiSGuidettiGConversoDProtective factors for work ability in preschool teachersOccup Med2017674301304

- McGonagleAKFisherGGBarnes-FarrellJLGroshJWIndividual and work factors related to work ability and labor force outcomesJ Appl Psychol2015100237639825314364

- AirilaAHakanenJJSchaufeliWBLuukkonenRPunakallioALusaSAre job and personal resources associated with work ability 10 years later? The mediating role of work engagementWork Stress201428187105

- DemeroutiEBakkerABNachreinerFSchaufeliWBThe job demands-resources model of burnoutJ Appl Psychol200186349951211419809

- Sjogren-RonkaTOjanenMTLeskinenEKMustalampiSTMälkiäEAPhysical and psychosocial prerequisites of functioning in relation to work ability and general subjective well-being among office workersScand J Work Environ Health200228318419012109558

- JanssenPPMSchaufeliWBHoukesIWork-related and individual determinants of the three burnout dimensionsWork Stress19991317486

- GibsonSDemboMTeacher efficacy: a construct validationJ Educ Psychol1984764569582

- BanduraASelf-Efficacy: The Exercise of ControlNew York, NYFreeman1997

- SkaalvikEMSkaalvikSDimensions of teacher self-efficacy and relations with strain factors, perceived collective teacher efficacy, and teacher burnoutJ Educ Psychol2007993611625

- GoddardRDGoddardYA multilevel analysis of the relationship between teacher and collective efficacy in urban schoolsTeach Teach Educ2001177807818

- ArmorDConroy-OsegueraPCoxMAnalysis of the School Preferred Reading Programs in Selected Los Angeles Minority Schools1976Rep No R-2007-LAUSDSanta Monica, CARand Corporation

- Tschannen-MoranMWoolfolk HoyAHoyWKTeacher efficacy: its meaning and measureRev Educ Res1998682202248

- RotterJBGeneralized expectancies for internal versus external control of reinforcementPsychol Monogr1996801128

- BanduraASelf-efficacy: toward a unifying theory of behavioral changePsychol Rev1977842191215847061

- ZeeMKoomenHMYTeacher self-efficacy and its effect on classroom processes, student academic adjustment, and teacher well-being: a synthesis of 40 years of researchRev Educ Res20168649811015

- CapraraGVBarbaranelliCStecaPMalonePSTeachers’ self-efficacy beliefs as determinants of job satisfaction and students’ academic achievement: a study at the school levelJ Sch Psychol2006446473490

- ReyesMRBrackettMARiversSEWhiteMSaloveyPClassroom emotional climate, student engagement, and academic achievementJ Educ Psychol20121043700712

- MartinNKSassDASchmittTATeacher efficacy in student engagement, instructional management, student stressors, and burnout: a theoretical model using in-class variables to predict teachers’ intent-to-leaveTeach Teach Educ2012284546559

- KünstingJNeuberVLipowskyFTeacher self-efficacy as a long-term predictor of instructional quality in the classroomEur J Psychol Educ2016313299322

- De JongRMainhardTvan TartwijkJVeldmanLVerloopNWubbelsTHow preservice teachers personality traits, self-efficacy, and discipline strategies contribute to the teacher-student relationshipBr J Educ Psychol201484229431024829122

- MashburnAJHamreBKDownerJTPiantaRCTeacher and classroom characteristics associated with teachers’ ratings of pre-kindergartners’ relationships and behaviorJ Psychoeduc Assess2006244367380

- AlmogOShechtmanZTeachers’ democratic and efficacy beliefs and styles of coping with behavioural problems of pupils with special needsEur J Spec Needs Educ2007222115129

- MalinenOSavolainenHXuJBeijing in-service teachers’ self-efficacy and attitudes towards inclusive educationTeach Teach Educ201224526534

- AvanziLMigliorettiMValscoVCross-validation of the Norwegian teacher’s self-efficacy scaleTeach Teach Educ20133116978

- BrouwersATomicWA longitudinal study of teacher burnout and perceived self-efficacy in classroom managementTeach Teach Educ2000162239253

- FivesHHammanDOlivaresADoes burnout begin with student-teaching? Analyzing efficacy, burnout, and support during the student-teaching semesterTeach Teach Educ2007236916934

- SchwarzerRHallumSPerceived Teacher self-efficacy as predictor of job stress and burnout: mediation analysesJ Appl Psychol Int Rev200857Suppl152171

- SkaalvikEMSkaalvikSTeacher self-efficacy and teacher burnout: a study of relationsTeach Teach Educ201026410591069

- SkaalvikEMSkaalvikSTeacher self-efficacy and perceived autonomy: relations with teacher engagement, job satisfaction, and emotional exhaustionPsychol Rep20141141687724765710

- WareHKitsantasATeacher and collective efficacy beliefs as predictors of professional commitmentJ Educ Res20071005303310

- KlassenRMChiuMMThe occupational commitment and intention to quit of practicing and pre-service teachers: influence of self-efficacy, job stress, and teaching contextContemp Educ Psychol2011362114129

- CollieRJShapkaJDPerryNESchool climate and social–emotional learning: predicting teacher stress, job satisfaction, and teaching efficacyJ Educ Psychol2012104411891204

- KlassenRWilsonESiuAFYPreservice teachers’ work stress, self-efficacy, and occupational commitment in four countriesEur J Psychol Educ201328412891309

- SkaalvikEMSkaalvikSTeacher stress and teacher self-efficacy as predictors of engagement, emotional exhaustion, and motivation to leave the teaching professionCreat Educ201671317851799

- De NeveDDevosGTuytensMThe importance of job resources and self-efficacy for beginning teachers’ professional learning in differentiated instructionTeach Teach Educ2015473041

- Tschannen-MoranMWoolfolk HoyAThe differential antecedents of self-efficacy beliefs of novice and experienced teachersTeach Teach Educ2007236944956

- ParkerKHannahEToppingKJCollective teacher efficacy, pupil attainment and socio-economic status in primary schoolImproving Schools200692111129

- GoddardRDHoyAKWoolfolk-HoyACollective teacher efficacy: its meaning, measure, and impact on student achievementAm J Educ Res2000372479507

- KlassenRMUsherELBongMTeachers’ collective efficacy, job satisfaction, and job stress in cross-cultural contextJ Exp Educ2010784464486

- LimSEoSThe mediating roles of collective teacher efficacy in the relations of teachers’ perceptions of school organizational climate to their burnoutTeach Teach Educ201444138147

- MalinenP-OSavolainenHThe effect of perceived school climate and teacher efficacy in behavior management on job satisfaction and burnout: a longitudinal studyTeach Teach Educ201660144152

- BanduraASocial cognitive theory: an agentic perspectiveAnnu Rev Psychol20015212611148297

- CapraraGVBarbaranelliCBorgogniLStecaPEfficacy beliefs as determinants of teachers’ job satisfactionJ Educ Psychol2003954821832

- StephanouGGkavrasGDoulkeridouMThe role of teachers’ self and collective-efficacy beliefs on their job satisfaction and experienced emotions in schoolPsychology201343A268278

- Viel-RumaHHouchinsDJolivetteKBensonGEfficacy beliefs of special educators: the relationships among collective efficacy, teacher self-efficacy, and job satisfactionTeach Educ Spec Educ2010333225233

- GoddardRDHoyWKWoolfolk HoyACollective efficacy beliefs: theoretical developments, empirical evidence, and future directionsEduc Res2004333313

- ColemanJSNorms as social capitalRadnittzkyGBernholzPEconomic Imperialism: The Economic Approach Applied Outside the Field of EconomicsNew York, NYParagon House Publishers1987

- BanduraASocial Foundations of Thoughts and Action A Social Cognitive TheoryEnglewood Cliffs, NJPrentice-Hall1976

- MarshHWWalkerRDebusRSubject specific components of academic self concept and self efficacyContemp Educ Psychol1991164331345

- SkaalvikEMBongMSelf-concept and self-efficacy revisited: a few notable differences and important similaritiesMarshHWCravenRGMcInerneyDMInternational Advances in Self ResearchGreenwichInformation Age200329

- LuthansFAveyJBAvolioBJNormaSMComsGMPsychological capital development: toward a micro-interventionJ Organ Behav2006273387393

- LevSKoslowskyMModerating the collective and self-efficacy relationshipJ Educ Adm Hist2004474452462

- BorgogniLPetittaLStecaPEfficacia personale e collettiva nei contesti organizzativi [Personal efficacy and Collective efficacy in organizational contexts]CapraraGVLa valutazione dell’autoefficacia [The Assessment of Self-Efficacy]Trento ITErickson2001265

- McGonagleAKFisherGGBarnes-FarrellJLGroschJWIndividual and work factors related to perceived work ability and labor force outcomesJ Appl Psychol2015100237639825314364

- ViottiSGil-MontePConversoDToward validating the Italian version of the “Spanish Burnout Inventory”: a preliminary study on an Italian nursing sampleRev Esc Enferm USP201549581982526516753

- ViottiSGuidettiGGil-MontePConversoDLa misurazione del burnout nei contesti sanitari: validità di costrutto e invarianza fattoriale della versione italiana dello Spanish Burnout Inventory (SBI-Ita). [Measuring burnout among health-care workers: construct validity and factorial invariance of the Italian version of the Spanish Burnout Inventory (SBI-Ita)Psicologiadella Salute201711123144

- PreacherKJHeyesAFSPSS and SAS procedures for estimating indirect effects in simple mediation modelsBehav Res Method Instrum Comput2004364717731

- BaronRMKennyDAThe moderator-mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: conceptual, strategic and statistical considerationJ Pers Soc Psychol1986516117311823806354

- BrunoADell’AversanaGReflective Practicum in higher education: the influence of the learning environment on the quality of learningAssess Eval High Educ2018433345358

- JungertTRosanderMSelf-efficacy and strategies to influence the study environmentTeach High Educ2010166647659

- TriandisHCIndividualism and CollectivismBoulder, COWestview Press1995