Abstract

Fibromyalgia syndrome (FMS) is a chronic disorder characterized by widespread and persistent musculoskeletal pain and other frequent symptoms such as fatigue, insomnia, morning stiffness, cognitive impairment, depression, and anxiety. FMS is also accompanied by different comorbidities like irritable bowel syndrome and chronic fatigue syndrome. Although some factors like negative events, stressful environments, or physical/emotional traumas may act as predisposing conditions, the etiology of FMS remains unknown. There is evidence of a high prevalence of psychiatric comorbidities in FMS (especially depression, anxiety, borderline personality, obsessive-compulsive personality, and post-traumatic stress disorder), which are associated with a worse clinical profile. There is also evidence of high levels of negative affect, neuroticism, perfectionism, stress, anger, and alexithymia in FMS patients. High harm avoidance together with high self-transcendence, low cooperativeness, and low self-directedness have been reported as temperament and character features in FMS patients, respectively. Additionally, FMS patients tend to have a negative self-image and body image perception, as well as low self-esteem and perceived self-efficacy. FMS reduces functioning in physical, psychological, and social spheres, and also has a negative impact on cognitive performance, personal relationships (including sexuality and parenting), work, and activities of daily life. In some cases, FMS patients show suicidal ideation, suicide attempts, and consummated suicide. FMS patients perceive the illness as a stigmatized and invisible disorder, and this negative perception hinders their ability to adapt to the disease. Psychological interventions may constitute a beneficial complement to pharmacological treatments in order to improve clinical symptoms and reduce the impact of FMS on health-related quality of life.

Video abstract

Point your SmartPhone at the code above. If you have a QR code reader the video abstract will appear. Or use:

Introduction

Fibromyalgia syndrome (FMS) is a chronic disorder characterized by widespread and persistent musculoskeletal pain that predominantly affects women (between 61% and 90%)Citation1 and has an estimated prevalence of 2%–4% in the general population.Citation2 Other associated symptoms are fatigue, insomnia, morning stiffness, depression, and anxiety.

FMS is frequently accompanied by other conditions such as irritable bowel syndrome, headache, fever, diarrhea, oral ulcers, dry eyes, vomit, constipation, skin rash, hearing difficulties, hair loss, painful and frequent urination, etc.Citation2 FMS is associated with high socioeconomic costs for the health system (medical visits, specialized consultations, diagnostic tests, drugs, and others therapies) and the workforce (sick leave, high rate of absenteeism, and decreased work-related productivity).Citation3,Citation4

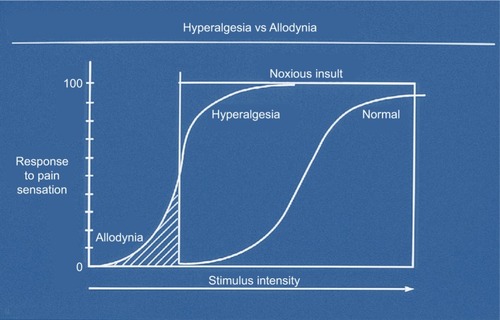

FMS was recognized as an illness by the WHO in 1992, being included in the ICD-10 under code number M79.Citation5 The etiology of FMS remains unknown. Current pathophysiological models assume a central sensitization to pain and impairments in endogenous pain inhibitory mechanismsCitation4,Citation6–Citation8 (). This idea is supported by the existence of hyperalgesia and allodynia, low thresholds and tolerance to pain, development of pain sensitization in the dorsal horns of the spinal cord in response to repeated pain, and greater brain responses to pain evocation observed in areas of the pain neuromatrix.Citation6–Citation8,Citation10,Citation11 However, other authors have considered neurological origin of FMS, based on the discovery of small fiberCitation12,Citation13 and large fiberCitation14 neuropathy in the affected patients.Citation12 Moreover, the involvement of idiopathic cerebrospinal pressure dysregulation in FMS pathology is discussed.Citation15 In 1990, the American Colleague of Rheumatology (ACR) established the first diagnostic criteria for FMS, wherein pain pressure up to 4 kg/cm2 was evaluated at 18 body points; pain elicited in at least eleven of them was required for a diagnosis.Citation16 However, these criteria were widely criticized due to the difficulties in using pressure algometry in primary health care and the limited predictive validity with respect to clinical pain.Citation17 Thus, in 2010, a new proposal was presented by the ACR exclusively based on the use of two scales: the Widespread Pain Index (WPI) and the Severity Scale (SS). The WPI includes a list of 19 painful areas and the SS involves an evaluation of the severity of certain clinical symptoms. For an FMS diagnosis, a WPI score ≥7 and SS score ≥5 or a WPI score between 3 and 6 and SS score ≥9 is needed. As with 1990 criteria, the symptoms must be present continuously over the period of at least 3 months.Citation2

Figure 1 Hyperalgesia and allodynia.

Vulnerability factors in fibromyalgia

Some factors seem to predispose individuals to FMS, such as accidents (traffic and work injuries, fractures, polytraumatisms), medical interventions and complications (such as from surgeries and infections), and emotional traumas (sexual and physical abuse and neglect).Citation18–Citation20 Environmental factors like stressful life events may be associated with FMS onset.Citation21,Citation22 FMS patients who report sexual or physical abuse tend to experience poorer psychological adjustment, greater psychological distress, and more severe clinical symptoms, and use more health care services.Citation23–Citation25 In general, studies have found an association between traumas during childhood and adolescence (not only abuse or violence, but also negligence and other negative life events) and level of disability in FMS.Citation26 Dysregulation of stress response mechanisms may antecede the development of FMS and other chronic conditions like chronic fatigue syndrome. Early stress in human development could alter stress mechanisms, leading to increased vulnerability to stress-related disorders. As such, lengthy trauma or life stress in childhood and adulthood seems to negatively affect brain modulatory systems, of both pain and emotions.Citation27 Though life experiences may partially explain the high prevalence of emotional disorders and alterations in pain modulation in FMS, the corresponding state of research does not allow definite conclusions.

FMS patients show blunted HPA (hypothalamus– pituitary–adrenal) reactivity (particularly at the pituitary level), which leads to an inappropriate cortisol response to stress or activities of daily living.Citation28,Citation29 FMS patients also displayed aberrant autonomic regulationCitation17 with lower activity of both the sympathetic and parasympathetic branches (such as higher heart rate and lower heart rate variability, blood pressure, stroke volume, etc) and reduced reactivity to physical and psychological stressors.Citation30,Citation31 This leads to a reduced capacity to face and cope successfully with environmental and daily life demands. Furthermore, the activity of the baroreflex, the main mechanism mediating the antinociceptive effect of blood pressure, is decreased.Citation26,Citation27 Moreover, the negative effect of negative life events seems to be enhanced and maintained due to the patients’ tendency toward catastrophizing,Citation10 avoidance, or inhibition of their emotions.Citation32

Physical inactivity and sedentary lifestyles, and the associated increase in body mass index (BMI), have been suggested as factors associated with FMS.Citation33,Citation34 Activity avoidance is associated with poorer function in individuals with chronic pain, and predicted poorer physical and psychological functioning and higher pain-related interference with daily life.Citation35 Overactive patterns can also contribute in the long term to increased risk of pain exacerbation, and patients with an overactive coping style when engaging in daily life activities usually report poorer physical and psychological function.Citation35 In contrast, patients who pace themselves (such as by slowing down and taking breaks to facilitate goal attainment) in their daily activities report lower pain interference and greater psychological function and pain control.Citation35

Family aggregation in FMS, suggesting genetic influences, has been observed.Citation36–Citation38 There is a greater prevalence of mood disorders (especially major depressive and bipolar disorders) and reduced pressure pain thresholds in the relatives of FMS patients. However, the specific genes and mechanisms of transmission are unknown, although they are probably polygenic, for instance, HLA antigen class I and II, DR4, 5-HTT, 5-HTTLPR, D2 receptor, catechol-O-methyltransferase polymorphism, etc.Citation36,Citation37

In spite of the evidence regarding the abovementioned predisposing factors (which cannot be considered causal), more research is needed to comprehensively understand their contribution to FMS origin and maintenance.Citation39

Impact on health-related quality of life

FMS negatively affects functioning at the physical, psychological, and social levels, impairing social relationships, ability to fulfill family and work responsibilities, daily life activities, and mental health, not only due to pain but also because of fatigue, cognitive deficits, and other associated symptoms.Citation40–Citation42 The quality of life of relatives can also be affected. Work is especially affected due to the tension between health problems (pain, fatigue, muscle weakness, limited physical capacity, increased stress, and increased need of rest) and work-related demands.Citation43,Citation44 It is important to provide familial and general social support to FMS workers, taking into account the fact that working patients show better health status and adaptation than non-working patients.Citation45,Citation46

FMS patients should have the opportunity to adjust their work situation and workload according to their reduced physical capacity for fulltime work, or decide definitively if they can or cannot work.Citation47,Citation48 In this vein, the WHO recommends workplace adjustments for health reasons.Citation49 FMS negatively affects sexual healthCitation50 and is related to reproduction problemsCitation51 and female sexual dysfunctions,Citation52,Citation53 such as hypoactive sexual desire,Citation54 sexual aversion, orgasm disorder, vaginismus, and dyspareunia.Citation55 Characteristic FMS symptoms (particularly widespread pain, fatigue, sleep disorders, and hypersensitivity and intolerability to tactile and pressure stimuli)Citation56 together with psychiatric comorbiditiesCitation57 (especially anxiety and depression),Citation58,Citation59 body image problems,Citation60 decreased lubrication,Citation61 pelvic floor muscle problems,Citation62 and medication side effects,Citation63 are some of the main causes of sexual problems (). With a multidisciplinary approach, it is necessary to treat sexual problems in FMS, as they are not only a cause of discomfort, which worsens symptoms and quality of life, but also lead to interpersonal problems and the breakup of couples.Citation64

Table 1 Biological and psychosocial aspects of FMS sexual dysfunctions

Cognitive impact of fibromyalgia

Lower cognitive performance has been found in FMS patients compared to healthy people.Citation33,Citation65,Citation66 FMS patients usually report cognitive impairments, especially problems in planning, attention, memory (in the working, semantic, and episodic domains), executive functions, and processing speed.Citation33,Citation67,Citation68 These findings accord with self-reported cognitive deficits, which usually include concentration difficulties, forgetfulness, decreased vocabulary, poor verbal fluency, and mental slowness.Citation69,Citation70 Nevertheless, the cognitive deficit does not seem to be global.Citation71 Additionally, higher levels of fatigue have been found during cognitive tasks in FMS patients compared to healthy people.Citation72

The main mediating factor of these cognitive deficits is the severity of clinical pain.Citation73–Citation75 Secondary explanatory factors are emotional-affective problems (particularly anxiety, depression, and negative emotional states),Citation76,Citation77 fatigue, and insomnia.Citation78–Citation80

Emotional and affective impact of fibromyalgia

FMS is linked to greater negative affect,Citation74–Citation76 which involves a general state of distress composed of aversive emotions like sadness, fear, anger, and guilt.Citation77 In addition, FMS patients tend to experience high levels of stress,Citation78,Citation79 anger (including anger-in or anger suppression, anger-out or anger expression, and angry rumination),Citation80–Citation82 and pain catastrophizing (conceptualized as an exaggerated negative orientation to pain, which provokes fear and discomfort and increases pain perception),Citation83 which are frequently associated with a worsening of symptoms,Citation84 including cognitive ones.Citation66

Psychiatric disorders can accompany rheumatic diseases and may increase disability and mortality, as well as reduce quality of life in these patients.Citation85,Citation86 FMS patients display a high rate of anxiety (20%–80%)Citation87 and depressive disorders (13%–63.8%).Citation88 Specifically, a higher prevalence in FMS patients than in the general population was observed for generalized anxiety disorder, panic attack, phobias,Citation89 obsessive compulsive disorder,Citation90 post-traumatic stress disorder,Citation90,Citation91 major depressive disorder,Citation92 dysthymia,Citation93 and bipolar disorders.Citation94,Citation95

The intensity of negative affective states is positively associated with increased pain intensity, irritability, physical and mental strain, functional limitations, the number of tender points, non-restorative sleep, cognitive deficits, fatigue, and the impact of the illness on quality of life.Citation90,Citation96,Citation97 FMS patients usually feel isolated, misunderstood, or rejected by relatives, friends, health workers, and society in general. This may contribute to the high prevalence of depression, along with the constant and intense pain.Citation90 There is also evidence of high levels of anxiety related to FMS patients’ heightened perception of pain and somatization of symptoms.Citation88

Chronic pain is a risk factor for suicidal behaviors.Citation98 In the case of FMS, the estimated prevalence of suicidal attempts has been reported as 16.7%,Citation99 rising to 58.3% in the case of FMS with comorbid migraine.Citation100 Thus, FMS patients have a higher rate of suicide attempts than the general population, where their risk of suicide is similar to that observed in other chronic diseases.Citation101 Suicidal behaviors in FMS include suicidal ideation,Citation102,Citation103 suicide attempts,Citation104 and death by suicide.Citation105,Citation106 The risk of suicide in FMS is increased due to the presence of a constellation of factors that are usually related to suicide, such as being female,Citation107 psychological distress, poor sleep quality,Citation108,Citation109 enhanced fatigue,Citation110 psychiatric comorbidities (especially depression, bipolar disorders, and borderline personality),Citation101,Citation108,Citation111 and physical comorbidities (like headache and gastric diseases).Citation101 Suicidal ideation is more common than suicide attemptsCitation112 and the latter occurs ten times more frequently than suicide.Citation113 Suicidal ideation in FMS is related to comorbid depression, anxiety, and a high negative impact on daily life activities.Citation103 The inclusion of FMS patients in suicide risk assessments in clinical practice, to prevent suicide, is an important consideration in clinical practice.

Personality, temperament, character, and fibromyalgia

Personality characteristics modulate an individual’s response to psychological stressorsCitation27 and adjustment to chronic illness.Citation27 An “FMS personality” is a topic that remains under debate. While some authors have found characteristic FMS traits,Citation27 others have failed to find any particular personality features.Citation114

Some personality disorders appear to be more prevalent in FMS patients than in the general population, including obsessive-compulsive personality disorder,Citation115,Citation116 borderline personality,Citation94 avoidant personality disorder,Citation117,Citation118 and histrionic personality disorder.Citation115 Some studies have observed a predominance of certain personality traits in FMS, such as perfectionism,Citation119,Citation120 alexithymia,Citation84,Citation121 neuroticism,Citation27,Citation122,Citation123 psychocitism,Citation123 avoidant personality traits,Citation115,Citation117,Citation118 and type D personalityCitation124 (which combine high negative affect with social inhibition).Citation125

Some studies have focused on the Big Five Model of Personality, which includes five dimensions: extraversion vs introversion, agreeableness vs antagonism, conscientiousness vs impulsivity, neuroticism vs emotional stability, and openness vs closed-mindedness.Citation126 In FMS, high neuroticism and low conscientiousness (high impulsivity) have been found, which seem to be related to high levels of chronic pain.Citation126 Furthermore, in some FMS patients, the high level of neuroticism is usually accompanied by low extraversion, contributing to more severe psychosocial problems.Citation127 Extraversion in FMS is associated with lower levels of pain, anxiety, and depression, and better mental health, thereby constituting a protective influence against FMS.Citation45 In general, the presence of personality disorders and negative personality traits in FMS is associated with poorer results after pain treatment,Citation128,Citation129 a worsening of the functional status, higher health care demands (particularly in terms of increased number of medical visits), and greater occupational and medical costs.Citation118,Citation130

Some studies have focused on the temperament and character of FMS patients, mainly based on Cloninger’s Personality Model, using the Temperament and Character Inventory.Citation131 High harm avoidance, high self-transcendence, low cooperativeness, and self-directedness have been found in FMS patients.Citation132–Citation134 Harm avoidance is related to pessimism, concerns about the future, fear of the unknown, and shyness. Self-transcendence can be conceptualized as spiritual ideas that involve a state of unified consciousness in which everything is an integral part of a totality, favoring a spiritual union with the universe. Self-transcendence has been associated with post-traumatic stress and psychotic symptoms, such as borderline, narcissistic, schizotypal, and paranoid symptoms.Citation135 Low levels of cooperativeness include social intolerance, lack of social interest, and a tendency to further their own interests. People with low self-directedness usually have difficulties in accepting responsibility and being independent, and show a lack of long-term goals, low motivation, and low self-esteem.Citation131

Impact of FMS on self-concept

The few studies available in this field have found lower self-esteemCitation66,Citation136,Citation137 levels in FMS patients. Lower self-esteem is related to a reduction of cognitive performance in FMS, especially in terms of attention, memory, and planning abilities.Citation66 FMS patients tend to experience a higher need to earn self-esteem through competence and others’ approval. It is known that self-esteem is related to self-confidence and self-efficacy expectations.Citation136,Citation137 Self-efficacy (the confidence one has in one’s ability to perform or resolve a specific behavior or problem)Citation138 or perceived self-efficacy (individuals’ beliefs in their capacities to achieve certain goals)Citation139 is usually low in FMS patients.Citation140,Citation141 Pain-related self-efficacy, conceptualized as beliefs about the ability to perform activities despite pain,Citation142 is also damaged in FMS.Citation140,Citation143 A high positive association has been found between self-efficacy and treatment adherence and improvements in FMS, with better self-efficacy being associated with more positive outcomes.Citation140,Citation141 Thus, interventions aimed at increasing self-esteem may be useful to improve expectations of self-efficacy and the patient’s own ability to manage their illness, thus promoting better adaptation to the disease.Citation144

Several studies have shown a precarious or negative self-image in FMS patients.Citation116,Citation145 Self-image problems are associated with the notion of an ill person, which radically alters FMS patients’ self-identity. Moreover, FMS patients’ self-image seems to be modified during the development and course of the illnessCitation146 and therapeutic interventions,Citation147 affecting their self-identity.Citation148 In spite of the relevance of the self-image concept, few studies to date have addressed this issue.

Body image is part of the overall self-image and is defined as the subjective perceptions, feelings, and thoughts about the physical body. It includes perceptual and affective compo nents,Citation149 which are usually affected in pain-related illnesses.Citation150 Indeed, there is evidence of a negative body image in FMS patients,Citation151,Citation152 further exacerbated by the high prevalence of overweight and obesity.Citation153,Citation154 FMS body image also seems to be influenced by the illness-affected body parts (especially painful and stiff areas), problems in cognitive function, negative health care experiences, activity limitations, and decreased quality of life.Citation151

Patient beliefs about fibromyalgia

The unknown etiology of FMS and the lack of objective diagnostic markers of the disease have led to a debate about its legitimacy and controversies regarding its true nature.Citation114 The negative experience of FMS patients is exacerbated due to the occasional perception that it is not a genuine disease.Citation155 Additionally, FMS patients cite the lack of physical markers of the illness as a reason for the delay in diagnosis and the source of doubts about the authenticity of the illness.Citation151 Many FMS patients report that their family and friends do not understand their disease;Citation156–Citation158 this lack of support could affect their functioning and recovery. Some studies have confirmed the relevance of support from family, friends, and health care staff for managing daily life with chronic illnesses, including FMS.Citation159,Citation160

In this way, FMS patients feel a double burden because their life is dominated by pain but it is not adequately acknowledged.Citation161 In fact, the process of FMS diagnosis is stressful for patients due to the lack of objective clinical markers and physician doubts, together with the general uncertainty of the process.Citation162 The majority of FMS patients feel relieved when they finally receive their FMS diagnosis. However, this relief tends to evaporate when they realize the ineffectiveness of treatments and the illness prognosis.Citation163,Citation164

Patients with FMS experience a sense of invisibility because of debates regarding the authenticity of the diagnosis, treatment, and health care in general.Citation155,Citation165 Moreover, FMS patients usually feel embarrassed because they are no longer able to perform daily tasks as before.Citation156 In fact, they have problems in planning daily life activities and interactions with family and their social circles due to the severity of their symptoms, such that they become more isolated.Citation157,Citation161,Citation166 Dissatisfaction with the patient–doctor relationship is another recurring problem, together with frustration due to uncertainty regarding the etiology and treatment of FMS.Citation164

FMS seems to undermine patients’ self-confidence and sense of selfCitation155 and disrupts their identity.Citation167 In this sense, FMS patients experience a transition or change in identity due to the illness, which is apparently invisible to the people who saw them when healthy due on the basis of their external or physical appearance.Citation168

Clearly, FMS patients can be perceived negatively, which worsens their symptoms and functioning. In their own words, they experience “illness intrusiveness” characterized as disruptions of valued activities, lifestyle, and interests, leading to compromised global quality of life. Evidence also suggests that feelings of vulnerability and apprehension about having a chronic illness of unknown origin may contribute to limiting patients’ activities, inability to sustain work, and somatic distress.Citation169,Citation170

Conclusion

FMS is associated with a high prevalence of emotional and affective disorders (particularly depression, anxiety, borderline personality, obsessive-compulsive personality, and post-traumatic stress disorder), and main symptoms and comorbidities may mutually reinforce each other. FMS reduces functioning in the physical, psychological, and social spheres, and has a negative impact on personal relationships (including sexuality and parenting), work, daily activities, and mental health. FMS patients also show problems in cognitive performance, especially in planning, attention, memory, executive functions, and processing speed. There is also evidence of high levels of negative affect, neuroticism, perfectionism, stress, anger, and alexithymia in FMS patients. High harm avoidance together with high self-transcendence, low cooperativeness, and low self-directedness have been found as temperament and character features of FMS patients. Furthermore, FMS patients tend to have a negative self-image and body image perception, as well as low self-esteem and perceived self-efficacy. In some cases, FMS patients show suicidal ideation, suicide attempts, and consummated suicide. FMS patients perceived the illness as a stigmatized and invisible disorder that is difficult to understand. The negative illness perception and lack of social support worsen their symptoms and functioning.

Due to the scarce etiological knowledge about FMS, there is currently no agreement about its appropriate therapy, and treatment effects have been claimed to be unsatisfactory.Citation171 However, various interventions, especially combinations of pharmacological with other types of treatments, may be helpful in reducing FMS symptoms and their impact on quality of life. Some evidence is available for positive effects of moderate aerobic exercise, cognitive-behavioral therapy, self-management programs, mindfulness training, and acceptance and commitment therapy.Citation3,Citation172 Furthermore, educative programs may help in increasing self-confidence, self-esteem, and pain self-efficacy.Citation173 Finally, FMS patients should stay active at the physical and social levels, and avoid sedentary lifestyles in order to control BMI and improve functioning and health-related quality of life.Citation174 However, further research is clearly warranted in order to establish a platform from which to develop guidelines regarding psychological interventions in FMS.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- WolfeFWalittBPerrotSRaskerJJHäuserWFibromyalgia diagnosis and biased assessment: sex, prevalence and biasPLoS One2018139e020375530212526

- WolfeFClauwDJFitzcharlesMAThe American College of rheumatology preliminary diagnostic criteria for fibromyalgia and measurement of symptom severityArthritis Care Res (Hoboken)201062560061020461783

- ArnoldLMGebkeKBChoyEHFibromyalgia: management strategies for primary care providersInt J Clin Pract2016709911226817567

- Galvez-SánchezCMDepression and trait-anxiety mediate the influence of clinical pain on health related quality of life in fibromyalgiaJ Affect Disord2019

- World Health OrganizationInternational Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Problems. ICD-10GenevaWHO1992

- de la CobaPBruehlSMoreno-PadillaMReyes Del PasoGAResponses to slowly repeated evoked pain stimuli in fibromyalgia patients: evidence of enhanced pain sensitizationPain Med20171891778178628371909

- de la CobaPBruehlSGalvez-SánchezCMReyes Del PasoGASlowly repeated evoked pain as a marker of central sensitization in fibromyalgia: diagnostic accuracy and reliability in comparison with temporal summation of painPsychosom Med201880657358029742751

- MontoroCIDuschekSde GuevaraCMReyes Del PasoGAPatterns of cerebral blood flow modulation during painful stimulation in fibromyalgia: a transcranial Doppler sonography studyPain Med201617122256226728025360

- MartinWJMalmbergABBasbaumAIPain: nocistatin spells reliefCurr Biol1998815R525R5279705926

- GracelyRHGeisserMEGieseckeTPain catastrophizing and neural responses to pain among persons with fibromyalgiaBrain2004127Pt 483584314960499

- De La CobaPBruehlSGalvez-SánchezCMReyes del PasoGASpecificity of slowly repeated evoked pain in comparison with traditional pain threshold and tolerance measures in fibromyalgia patientsPsychosom Med201880657358029742751

- FarhadKOaklanderALFibromyalgia and small-fiber polyneuropathy: what’s in a name?Muscle Nerve201858561161329938813

- Martínez-LavínMFibromyalgia and small fiber neuropathy: the plot thickensClin Rheumatol201837123167317130238382

- CaroXJGalbraithRGWinterEFEvidence of peripheral large nerve involvement in fibromyalgia: a retrospective review of EMG and nerve conduction findings in 55 FM subjectsEur J Rheumatol20185210411030185358

- HulensMDankaertsWStalmansIFibromyalgia and unexplained widespread pain: the idiopathic cerebrospinal pressure dysregulation hypothesisMed Hypotheses201811015015429317060

- WolfeFSmytheHAYunusMBThe American College of rheumatology 1990 criteria for the classification of fibromyalgiaArthritis Rheum19903321601722306288

- GracelyRHPetzkeFWolfJMClauwDJFunctional magnetic resonance imaging evidence of augmented pain processing in fibromyalgiaArthritis Rheum20024651333134312115241

- RaphaelKGJanalMNNayakSSchwartzJEGallagherRMPsychiatric comorbidities in a community sample of women with fibromyalgiaPain20061241–211712516698181

- NicolsonNADavisMCKruszewskiDZautraAJChildhood maltreatment and diurnal cortisol patterns in women with chronic painPsychosom Med201072547148020467005

- LowLASchweinhardtPEarly life adversity as a risk factor for fibromyalgia in later lifePain Res Treat2012201214083222110940

- AlbrechtPJRiceFLFibromyalgia syndrome pathology and environmental influences on afflictions with medically unexplained symptomsRev Environ Health201631228129427105483

- GuptaASilmanAJPsychological stress and fibromyalgia: a review of the evidence suggesting a neuroendocrine linkArthritis Res Ther2004639810615142258

- TheoharidesTCTsilioniIArbetmanLPanagiotidouSFibromyalgia, a syndrome in search of pathogenesis and therapyJ Pharmacol Exp Ther201535525526326306765

- HäuserWGalekAErbslöh-MöllerBPosttraumatic stress disorder in fibromyalgia syndrome: prevalence, temporal relationship between posttraumatic stress and fibromyalgia symptoms, and impact on clinical outcomePain201315481216122323685006

- WilliamsDAClauwDJUnderstanding fibromyalgia: lessons from the broader pain research communityJ Pain200910877779119638325

- GonzalezBBaptistaTMBrancoJCFerreiraASFibromyalgia: antecedent life events, disability, and causal attributionPsychol Health Med201318446147023323642

- MalinKLittlejohnGOPersonality and fibromyalgia syndromeOpen Rheumatol J20126127328523002409

- Van HoudenhoveBPremorbid “overactive” lifestyle and stress-related pain/fatigue syndromesJ Psychosom Res200558438939015992575

- Van HoudenhoveBEgleUTFibromyalgia: a stress disorder? piecing the biopsychosocial puzzle togetherPsychother Psychosom200473526727515292624

- Reyes Del PasoGAGarridoSPulgarAMartín-VázquezMDuschekSAberrances in autonomic cardiovascular regulation in fibromyalgia syndrome and their relevance for clinical pain reportsPsychosom Med201072546247020467004

- Reyes del PasoGAGarridoSPulgarÁDuschekSPulgarAAutonomic cardiovascular control and responses to experimental pain stimulation in fibromyalgia syndromeJ Psychosom Res201170212513421262414

- HorowitzMJStress-response syndromes: a review of posttraumatic and adjustment disordersHosp Community Psychiatry19863732412493957267

- MorkPJVasseljenONilsenTILAssociation between physical exercise, body mass index, and risk of fibromyalgia: longitudinal data from the Norwegian Nord-Trøndelag health studyArthritis Care Res (Hoboken)201062561161720191480

- Muñoz Ladrón de GuevaraCFernández-SerranoMJReyes del PasoGADuschekSExecutive function impairments in fibromyalgia syndrome: relevance of clinical variables and body mass indexPLoS One2018134e019632929694417

- RacineMGalánSde la VegaRPain-related activity management patterns and function in patients with fibromyalgia syndromeClin J Pain201834212212928591081

- ArnoldLMHudsonJIHessEVFamily study of fibromyalgiaArthritis Rheum200450394495215022338

- BuskilaDSarzi-PuttiniPBiology and therapy of fibromyalgia genetic aspects of fibromyalgia syndromeArthritis Res Ther20068521816887010

- ArnoldLMFanJRussellIJThe fibromyalgia family study: a genome-wide linkage scan studyArthritis Rheum20136541122112823280346

- WolfeFHäuserWWalittBTKatzRSRaskerJJRussellASFibro-myalgia and physical trauma: the concepts we inventJ Rheumatol20144191737174525086080

- FreitasRPAAndradeSCSpyridesMHCAlbuquerque BarbosaMTSousaMBCImpacts of social support on symptoms in Brazilian women with fibromyalgiaRev Bras Rheumatol2017573197203

- KarperWBEffects of exercise, patient education, and resource support on women with fibromyalgia: an extended long-term studyJ Women Aging201628655556227749200

- NeuprezACrielaardJMFibromyalgie: état de la question en 2017 [Fibromyalgia: state of the issue in 2017]Rev Med Liege2017726288294 French28628285

- MannerkorpiKGardGHinders for continued work among persons with fibromyalgiaBMC Musculoskelet Disord20121319622686369

- HenrikssonCMLiedbergGMGerdleBWomen with fibromyalgia: work and rehabilitationDisabil Rehabil2005271268569416012061

- IlmarinenJWork ability – a comprehensive concept for occupational health research and preventionScand J Work Environ Health20093511519277432

- JuusoPSkärLSundinKSöderbergSThe workplace experiences of women with fibromyalgiaMusculoskeletal Care2016142697626756399

- PalstamABjersingJLMannerkorpiKWhich aspects of health differ between working and nonworking women with fibromyalgia? A cross-sectional study of work status and healthBMC Public Health2012121107623237146

- ReisineSFifieldJWalshSForrestDDEmployment and health status changes among women with fibromyalgia: a five-year studyArthritis Rheum200859121735174119035427

- World Health OrganizationHealthy workplace. Framework and Model. Background and supporting literature and practice 2010 Available from: http://www.who.int/occupationalhealth/evelynhwpspanish.pdfAccessed September 20, 2018

- ZielinskiREAssessment of women’s sexual health using a holistic, patient-centered approachJ Midwifery Womens Health201358332132723758720

- ShaverJLWilburJRobinsonFPWangEBuntinMSWomen’s health issues with fibromyalgia syndromeJ Womens Health (Larchmt)20061591035104517125422

- KalichmanLAssociation between fibromyalgia and sexual dysfunction in womenClin Rheumatol200928436536919165555

- Rico-VillademorosFCalandreEPRodríguez-LópezCMSexual functioning in women and men with fibromyalgiaJ Sex Med20129254254922023737

- BurriAGrevenCLeupinMSpectorTRahmanQA multivariate twin study of female sexual dysfunctionJ Sex Med20129102671268122862825

- IncesuCSexual function and dysfunctionsKlinik Psikiyatri2004Ek3313

- RosenbaumTYMusculoskeletal pain and sexual function in womenJ Sex Med201072 Pt 164565319751383

- LewisRWFugl-MeyerKSBoschREpidemiology/risk factors of sexual dysfunctionJ Sex Med200411353916422981

- MongaTNTanGOstermannHJMongaUGraboisMSexuality and sexual adjustment of patients with chronic painDisabil Rehabil19982093173299664190

- AmblerNWilliamsACHillPGunaryRCratchleyGSexual difficulties of chronic pain patientsClin J Pain200117213814511444715

- YilmazHYilmazSDPolatHASalliAErkinGUgurluHThe effects of fibromyalgia syndrome on female sexuality: a controlled studyJ Sex Med20129377978522240036

- BurriALachanceGWilliamsFMPrevalence and risk factors of sexual problems and sexual distress in a sample of women suffering from chronic widespread painJ Sex Med201411112772278425130789

- LisboaLLSoneharaEOliveiraKCAndradeSCAzevedoGDKinesiotherapy effect on quality of life, sexual function and climacteric. Clinical nursing research symptoms in women with fibromyalgiaRev Bras Rheumatol201555209215

- BazzichiLGiacomelliCRossiAFibromyalgia and sexual problemsReumatismo201264426126723024970

- PohLWHeHGChanWCSExperiences of patients with rheumatoid arthritis: a qualitative studyClin Nurs Res201726337339326862118

- GlassJMFibromyalgia and cognitionJ Clin Psychiatry200869Suppl 22024

- Galvez-SánchezCMReyes Del PasoGADuschekSCognitive impairments in fibromyalgia syndrome: associations with positive and negative affect, Alexithymia, pain Catastrophizing and self-esteemFront Psychol2018937729623059

- GlassJMParkDCMinearMCroffordLJMemory beliefs and function in fibromyalgia patientsJ Psychosom Res200558326326915865951

- DaileyDLKeffalaVJSlukaKADo cognitive and physical fatigue tasks enhance pain, cognitive fatigue, and physical fatigue in people with fibromyalgia?Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken)201567228829625074583

- DuschekSWernerNSWinkelmannAWanknerSImplicit memory function in fibromyalgia syndromeBehav Med2013391111623398271

- Munguía-IzquierdoDLegaz-ArreseAMoliner-UrdialesDReverter-MasíaJNeuropsicología de los pacientes con síndrome de fibromialgia: relación con dolor y ansiedad [Neuropsychological performance in patients with fibromyalgia syndrome: relation to pain and anxiety]Psicothema2008203427431 Spanish18674438

- Reyes Del PasoGAPulgarÁDuschekSGarridoSCognitive impairment in fibromyalgia syndrome: the impact of cardiovascular regulation, pain, emotional disorders and medicationEur J Pain201216342142922337559

- Peñacoba PuenteCVelasco FurlongLÉcija GallardoCCigarán Mén-dezMBedmar CruzDFernández-de-Las-PeñasCSelf-efficacy and affect as mediators between pain dimensions and emotional symptoms and functional limitation in women with fibromyalgiaPain Manag Nurs2015161606825179423

- HassettALSimonelliLERadvanskiDCBuyskeSSavageSVSigalLHThe relationship between affect balance style and clinical outcomes in fibromyalgiaArthritis Rheum200859683384018512724

- FinanPHZautraAJDavisMCDaily affect relations in fibromyalgia patients reveal positive affective disturbancePsychosom Med200971447448219251863

- MalinKLittlejohnGOStress modulates key psychological processes and characteristic symptoms in females with fibromyalgiaClin Exp Rheumatol2013316 Suppl 796471

- WatsonDClarkLATellegenADevelopment and validation of brief measures of positive and negative affect: the PANAS scalesJ Pers Soc Psychol1988546106310703397865

- GlassJMReview of cognitive dysfunction in fibromyalgia: a convergence on working memory and attentional control impairmentsRheum Dis Clin North Am200935229931119647144

- KivimäkiMLeino-ArjasPVirtanenMWork stress and incidence of newly diagnosed fibromyalgia: prospective cohort studyJ Psychosom Res200457541742215581643

- Van HoudenhoveBEgleULuytenPThe role of life stress in fibro-myalgiaCurr Rheumatol Rep20057536537016174484

- RicciABoniniSContinanzaMWorry and anger rumination in fibromyalgia syndromeReumatismo201668419519828299918

- van MiddendorpHLumleyMAJacobsJWvan DoornenLJBijlsmaJWGeenenREmotions and emotional approach and avoidance strategies in fibromyalgiaJ Psychosom Res200864215916718222129

- SayarKGulecHTopbasMAlexithymia and anger in patients with fibromyalgiaClin Rheumatol200423544144815278756

- BaastrupSSchultzRBrødsgaardIA comparison of coping strategies in patients with fibromyalgia, chronic neuropathic pain, and pain-free controlsScand J Psychol201657651652227558974

- MontoroCIReyes del PasoGADuschekSAlexithymia in fibromyalgia syndromePers Individ Dif2016102170179

- AngDCChoiHKroenkeKWolfeFComorbid depression is an independent risk factor for mortality in patients with rheumatoid arthritisJ Rheumatol20053261013101915940760

- BazzichiLMaserJPiccinniAQuality of life in rheumatoid arthritis: impact of disability and lifetime depressive spectrum symptomatologyClin Exp Rheumatol200523678378816396695

- FiettaPFiettaPManganelliPFibromyalgia and psychiatric disordersActa Biomed2007782889517933276

- UçarMSarpÜKaraaslanÖGülAITanikNArikHOHealth anxiety and depression in patients with fibromyalgia syndromeJ Int Med Res201543567968526249741

- Pando-FernándezMPFibromyalgia and psychotherapyRev Digit Med Psicosom Psicoter20111142

- CoppensEVan WambekePMorlionBPrevalence and impact of childhood adversities and post-traumatic stress disorder in women with fibromyalgia and chronic widespread painEur J Pain20172191582159028543929

- GalekAErbslöh-MöllerBMental disorders in patients with fibromyalgia syndrome: screening in centers of different medical specialtiesSchmerz Berl Ger201327296304

- SteinerJLSmBSlavenJEThe complex relationship between pain intensity and physical functioning in fibromyalgia: the mediating role of depressionJ Appl Biobehav Res2017112

- Soriano-MaldonadoAAmrisKOrtegaFBAssociation of different levels of depressive symptoms with symptomatology, overall disease severity, and quality of life in women with fibromyalgiaQual Life Res201524122951295726071756

- AlciatiASarzi-PuttiniPBatticciottoAOveractive lifestyle in patients with fibromyalgia as a core feature of bipolar spectrum disorderClin Exp Rheumatol2012306 Suppl 7412212823261011

- Di Tommaso MorrisonMCCarinciFLessianiGFibromyalgia and bipolar disorder: extent of comorbidity and therapeutic implicationsJ Biol Regul Homeost Agents20173111720

- ThiemeKTurkDCFlorHComorbid depression and anxiety in fibromyalgia syndrome: relationship to somatic and psychosocial variablesPsychosom Med200466683784415564347

- StaudRKooERobinsonMEPriceDDSpatial summation of mechanically evoked muscle pain and painful aftersensations in normal subjects and fibromyalgia patientsPain20071301–217718717459587

- KyeSYParkKSuicidal ideation and suicidal attempts among adults with chronic diseases: a cross-sectional studyCompr Psychiatry20177316016727992846

- KurthTScherAISuicide risk is elevated in migraineurs who have comorbid fibromyalgiaNeurology201585121012101326296512

- Jimenez-RodríguezIGarcía-LeivaJMJiménez-RodríguezBMCondés-MorenoERico-VillademorosFCalandreEPSuicidal ideation and the risk of suicide in patients with fibromyalgia: a comparison with non-pain controls and patients suffering from low-back painNeuropsychiatr Dis Treat20141062563024790444

- Chen-ChiaLChun-HungTJiunn-HorngCHA nationwide population-based cohort studyMedicine20169544e518727858855

- CalandreEPNavajas-RojasMABallesterosJGarcia-CarrilloJGar-cia-LeivaJMRico-VillademorosFSuicidal ideation in patients with fibromyalgia: a cross-sectional studyPain Pract201515216817424433278

- TriñanesYGonzález-VillarAGómez-PerrettaCCarrillo-de-La-PeñaMTSuicidality in chronic pain: predictors of suicidal ideation in fibromyalgiaPain Pract201515432333224690160

- CalandreEPVilchezJSMolina-BareaRSuicide attempts and risk of suicide in patients with fibromyalgia: a survey in Spanish patientsRheumatology (Oxford)201150101889189321750003

- DreyerLKendallSDanneskiold-SamsøeBBartelsEMBliddalHMortality in a cohort of Danish patients with fibromyalgia: increased frequency of suicideArthritis Rheum201062103101310820583101

- WolfeFHassettALWalittBMichaudKMortality in fibromyalgia: a study of 8,186 patients over thirty-five yearsArthritis Care Res201163194101

- NockMKBorgesGBrometEJChaCBKesslerRCLeeSSuicide and suicidal behaviorEpidemiol Rev200830113315418653727

- PigeonWRPinquartMConnerKMeta-analysis of sleep disturbance and suicidal thoughts and behaviorsJ Clin Psychiatry2012739e1160e116723059158

- WojnarMIlgenMAWojnarJMcCammonRJValensteinMBrowerKJSleep problems and suicidality in the National comorbidity survey replicationJ Psychiatr Res200943552653118778837

- KleimanEMTurnerBJChapmanALNockMKFatigue moderates the relationship between perceived stress and suicidal ideation: evidence from two high-resolution studiesJ Clin Child Adolesc Psychol201847111613028715280

- BoltonJMWalldRChateauDFinlaysonGSareenJRisk of suicide and suicide attempts associated with physical disorders: a population-based, balancing score-matched analysisPsychol Med201545349550425032807

- HawtonKvan HeeringenKSuicideThe Lancet2009373967213721381

- NockMKBorgesGBrometEJCross-national prevalence and risk factors for suicidal ideation, plans and attemptsBr J Psychiatry200819229810518245022

- JohannssonVDoes a fibromyalgia personality exist?J Musculoskel Pain199313–4245252

- UguzFCiçekESalliAAxis I and axis II psychiatric disorders in patients with fibromyalgiaGen Hosp Psychiatry201032110510720114137

- HellströmOBullingtonJKarlssonGLindqvistPMattssonBA phenomenological study of fibromyalgia. Patient perspectivesScandinavian J Primary Health Care20091711116

- FuTGambleHSiddiquiUSchwartzTPsychiatric and personality disorder survey of patients with fibromyalgiaAnnals Depres Anxiet2015261064

- Gumà-UrielLPeñarrubia-MaríaMTCerdà-LafontMImpact of IPDE-SQ personality disorders on the healthcare and societal costs of fibromyalgia patients: a cross-sectional studyBMC Fam Pract20161716127245582

- HerkenHGürsoySYetkinOEoeViritOEsgiKPersonality characteristics and depression level of the female patients with fibromyalgia syndromeInt Med J200184144

- SiroisFMMolnarDSPerfectionism and maladaptive coping styles in patients with chronic fatigue syndrome, irritable bowel syndrome and fibromyalgia/arthritis and in healthy controlsPsychother Psychosom201483638438525323951

- CastelliLTesioVColonnaFAlexithymia and psychological distress in fibromyalgia: prevalence and relation with quality of lifeClin Exp Rheumatol2012306 Suppl 74707723110722

- VuralMBerkolTDErdogduZKucukseratBAksoyCEvaluation of personality profile in patients with fibromyalgia syndrome and healthy controlsMod Rheumatol201424582382824372295

- MontoroCIReyes del PasoGAPersonality and fibromyalgia: relationships with clinical, emotional, and functional variablesPers Individ Dif201585236244

- van MiddendorpHKoolMBvan BeugenSDenolletJLumleyMAGeenenRPrevalence and relevance of type D personality in fibromyalgiaGen Hosp Psychiatry201639667226804772

- DenolletJDS14: standard assessment of negative affectivity, social inhibition, and type D personalityPsychosom Med2005671899715673629

- BucourtEMartailléVMullemanDComparison of the big five personality traits in fibromyalgia and other rheumatic diseasesJoint Bone Spine201784220320727269650

- TorresXBaillesEValdesMPersonality does not distinguish people with fibromyalgia but identifies subgroups of patientsGen Hosp Psychiatry201335664064824035635

- ElliottTRJacksonWTLayfieldMKendallDPersonality disorders and response to outpatient treatment of chronic painJ Clin Psychol Med Settings19963321923424226759

- UomotoJMTurnerJAHerronLDUse of the MMPI and MCMI in predicting outcome of lumbar laminectomyJ Clin Psychol19884421911972966184

- UguzFKucukACicekEQuality of life in rheumatological patients: the impact of personality disordersInt J Psychiatry Med201549319920725930734

- CloningerCPersonality and PsychopathologyWashington, DCAmerican Psychiatric Press, Inc1999

- Gencay-CanACanSSTemperament and character profile of patients with fibromyalgiaRheumatol Int201232123957396122200811

- BalbalogluOTanikNAlpayciMHakanAKKaraahmetEInanLEParesthesia frequency in fibromyalgia and its effects on personality traitsInt J Rheum Dis20182171343134929968325

- Garcia-FontanalsAGarcía-BlancoSPortellMCloninger’s psychobiological model of personality and psychological distress in fibromyalgiaInt J Rheum Dis201619985286325483854

- YoonSJJunCSAnHYKangHRJunTYPatterns of temperament and character in patients with posttraumatic stress disorder and their association with symptom severityCompr Psychiatry200950322623119374966

- MichielsenHJvan HoudenhoveBLeirsIVandenbroeckAOnghenaPDepression, attribution style and self-esteem in chronic fatigue syndrome and fibromyalgia patients: is there a link?Clin Rheumatol200625218318816010445

- GaraigordobilMFibromialgia: discapacidad funcional, autoestima Y perfil de personalidad [Fibromyalgia: functional disability, self-esteem and personality profile]Inf Psicol2013106416 Spanish

- BanduraASocial Foundations of Thought and Action: A Social Cognitive TheoryEnglewood Cliffs, NJPrentice-Hall1986

- BanduraASelf-efficacy: The Exercise of ControlNew YorkFreeman1997

- MannerkorpiKSvantessonUBrobergCRelationships between Performance-based tests and patients’ ratings of activity limitations, self-efficacy, and pain in fibromyalgiaArch Phys Med Rehabil200687225926416442982

- RasmussenMUAmrisKRydahl-HansenSAre the changes in observed functioning after multi-disciplinary rehabilitation of patients with fibromyalgia associated with changes in pain self-efficacy?Dis-abil Rehabil2017391717441752

- BanduraAO’LearyATaylorCBGauthierJGossardDPerceived self-efficacy and pain control: opioid and nonopioid mechanismsJ Pers Soc Psychol19875335635712821217

- VongSKCheingGLChanCCChanFLeungASMeasurement structure of the pain self-efficacy questionnaire in a sample of Chinese patients with chronic painClin Rehabil200923111034104319656814

- DenisonEAsenlöfPLindbergPSelf-efficacy, fear avoidance, and pain intensity as predictors of disability in subacute and chronic musculoskeletal pain patients in primary health carePain2004111324525215363867

- BaptistaASJonesAJonesAJonesAEffectiveness of dance in patients with fibromyalgia: a randomized, single-blind, controlled studyJ Natour Clin Exp Rheumatol2012306 Suppl 741823

- Bojner HorwitzEKowalskiJTheorellTAnderbergUMDance/ movement therapy in fibromyalgia patients: changes in self-figure Drawings and their relation to verbal self-rating scalesArts Psycho-ther20063311125

- Van HoudenhoveBNeerinckxEOnghenaPVingerhoetsALysensRVertommenHDaily hassles reported by chronic fatigue syndrome and fibromyalgia patients in tertiary care: a controlled quantitative and qualitative studyPsychother Psychosom200271420721312097786

- AsbringPChronic illness – a disruption in life: identity-transformation among women with chronic fatigue syndrome and fibromyalgiaJ Adv Nurs200134331231911328436

- GroganSBody image and health: contemporary perspectivesJ Health Psychol200611452353016769732

- LotzeMMoseleyGLRole of distorted body image in painCurr Rheumatol Rep20079648849618177603

- BoyingtonJESchosterBCallahanLFComparisons of body image perceptions of a sample of black and white women with rheumatoid arthritis and fibromyalgia in the USOpen Rheumatol J2015911725674181

- NeumannLLernerEGlazerYBolotinASheferABuskilaDA cross-sectional study of the relationship between body mass index and clinical characteristics, tenderness measures, quality of life, and physical functioning in fibromyalgia patientsClin Rheumatol200827121543154718622575

- KimCHLuedtkeCAVincentAThompsonJMOhTHAssociation of body mass index with symptom severity and quality of life in patients with fibromyalgiaArthritis Care Res (Hoboken)201264222222821972124

- OkifujiABradshawDHOlsonCEvaluating obesity in fibromyalgia: neuroendocrine biomarkers, symptoms, and functionsClin Rheumatol200928447547819172342

- LemppHKHatchSLCarvilleSFChoyEHPatients’ experiences of living with and receiving treatment for fibromyalgia syndrome: a qualitative studyBMC Musculoskelet Disord200910112419811630

- ArnoldLMCroffordLJMeasePJPatient perspectives on the impact of fibromyalgiaPatient Educ Couns200873111412018640807

- SöderbergSStrandMHaapalaMLundmanBLiving with a woman with fibromyalgia from the perspective of the husbandJ Adv Nurs200342214315012670383

- ThorneSEHarrisSRMahoneyKConAMcGuinnessLThe context of health care communication in chronic illnessPatient Educ Couns200454329930615324981

- SkuladottirHHalldorsdottirSThe quest for well-being: self-identified needs of women in chronic painScand J Caring Sci2011251819120409049

- WestCStewartLFosterKUsherKThe meaning of resilience to persons living with chronic pain: an interpretive qualitative inquiryJ Clin Nurs2012219–101284129222404312

- JuusoPSkärLOlssonMSöderbergSLiving with a double burden: meanings of pain for women with fibromyalgiaInt J Qual Stud Health Wellbeing2011637184

- SimJMaddenSIllness experience in fibromyalgia syndrome: a metasynthesis of qualitative studiesSoc Sci Med2008671576718423826

- MengshoelAMSimJAhlsenBMaddenSDiagnostic experience of patients with fibromyalgia: a meta-ethnographyChronic Illn201814319421128762775

- Briones-VozmedianoEVives-CasesCRonda-PérezEPatients’ and professionals’ views on managing fibromyalgiaPain Res Manag2013181192423457682

- ArmentorJLLiving with a contested, stigmatized illness: experiences of managing relationships among women with fibromyalgiaQual Health Res201727446247326667880

- SöderbergSLundmanBNorbergAThe meaning of fatigue and tiredness as narrated by women with fibromyalgia and healthy womenJ Clin Nurs200211224725511903724

- ÅsbringPChronic illness – a disruption in life: identity-transformation among women with chronic fatigue syndrome and fibromyalgiaJ Adv Nurs200134331231911328436

- SöderbergSLundmanBTransitions experienced by women with fibromyalgiaHealth Care Women Int200122761763112141840

- DevinsGEnhancing personal control and minimizing illness intrusivenessKutnerNCardenasDBowerJMaximizing Rehabilitation in Chronic Renal DiseaseNew YorkPMA Publishing1989109136

- DevinsGMPsychologically meaningful activity, illness intrusiveness, and quality of life in rheumatic diseasesArthritis Rheum200655217217416583378

- Álvarez-GallardoICBidondeJBuschATherapeutic validity of exercise interventions in the management of fibromyalgiaJ Sports Med Phys Fitness Epub2018101

- GonzálezEElorzaJFaildeIComorbilidad psiquiátrica Y Fibromialgia. SU efecto sobre La calidad de vida de Los pacientes [Psychiatric comorbidity and Fibromyalgia and Its effect on the quality of life of patients]Actas Esp Psiquiatr201038295300 Spanish21117004

- AssumpçãoAPaganoTMatsutaniLAFerreiraEAPereiraCAMarquesAPQuality of life and discriminating power of two questionnaires in fibromyalgia patients: fibromyalgia impact Questionnaire and medical outcomes study 36-Item short-form health surveyRev Bras Fisioter201014428428920949228

- CarvilleSFArendt-NielsenLBliddalHEULAREULAR evidence-based recommendations for the management of fibromyalgia syndromeAnn Rheum Dis200867453654117644548