Abstract

Purpose

Employee voice has been considered as an important means to understand the cutting-edge information, gain social status and performance advantage for leaders, employees and the organization, respectively. However, our knowledge about how and when employees’ emotions influence voice remains limited.

Design/Methodology/Approach

In order to better illustrate the role of emotion on voice, based on emotion as social information theory and similarity attraction theory, we proposed a research model through which emotion recognition ability affects voice via perceived ambidextrous leadership. A sample of 182 comprised of full-time employees and their 43 immediate supervisors was collected through questionnaires in China, and analyzed via hierarchical regression method.

Findings

We found that subordinate’s emotional recognition ability has a significant positive effect on promotive and prohibitive voice, and that perceived ambidextrous leadership plays a significant mediating role between subordinate’s emotional recognition ability and promotive voice, while no mediating role is found between subordinate’s emotional recognition ability and prohibitive voice. In addition, in contrast to leader-subordinate gender dissimilarity, leader-subordinate gender similarity is more effective in strengthening the impact of emotion recognition ability on perceived ambidextrous leadership, and thus promotes employee voice.

Originality/Value

This research not only advances our understanding of employee voice, but also provides specific reference for management practices from the perspective of gender.

Introduction

During the period of huge organizational transformation and adjustment, high environmental uncertainty make it inadequate for leaders to make accurate decision merely relying on information they grasp, which highlights the importance of subordinates’ voice.Citation1,Citation2 Furthermore, numerous companies have regarded voice as an important indicator for employee promotion and salary increase, such as Huawei. Given the significance of voice, prior studies have examined its triggering mechanisms from multiple perspectives. For example, based on the constructive intention of voice, some scholars suggested that employee’s perceived insider status and psychological safety constitute the basis of voice.Citation3,Citation4 In contrast, according to self-interested voice, there are studies stating that employee voice aims to gain high performance and social status.Citation5,Citation6

Although researchers have attempted to demystify the antecedents of employee voice, existing studies seldom focus on the promotive or prohibitive effects of emotion on voice. In particular, employees’ emotional perception and emotional understanding of their leaders are lacking. Drawing on emotion as social information theory, emotions have a social signal function,Citation7 and leaders’ emotional changing means a lot to employees. According to previous studies, the social reference effect of information enables to reduce employee’s behavioral decision-making deviation significantly,Citation8 which further contributes to a win-win situation through voice.Citation9 A study from Harvard Business Review suggests that “reading facial expressions” is a vital approach for employees to assess the risk of their voice.Citation10 If employees capture the negative emotions of their leaders, they usually adopt a tepid work attitude owing to the consideration of psychological risk and resource loss.Citation11,Citation12 Emotional recognition ability refers to an individual’s ability to perceive and understand other people’s emotions accurately, and thus guide his/her own behaviors.Citation13

According to emotion as social information theory, it must be through a complex mechanism of emotional information process from “reading leaders’ expressions” to employee voice.Citation14 A work from Harvard Business Review has unveiled the mechanism of leader emotions on employee behavioral decision-making.Citation10 It stated that the open-loop character of cerebral limbic system enables employees to dig into the behavioral tendency from their leaders’ emotions, through which employees evaluate their voice risk. According to Meindl,Citation15 leadership is in essence kind of perception constructed by subordinates subjectively, and resides in their mind for a long time. Wong and LawCitation13 suggested that

employees’ recognition of their leaders’ emotional changing profoundly affects the quality of leadership behavior perception, and employees’ perceptions on leader behavior vary over time and contexts.

Thus, we assume that perceived ambidextrous leadership may bridge between “reading leaders’ expressions” and employee voice. Furthermore, due to gender differences, leader-subordinate gender (dis) similarity may have different impacts on the process from “reading leaders’ expressions” to employee voice.Citation16,Citation17 Based on similarity attraction theory,Citation17 subordinates having the same gender with their leaders are more likely to gain interaction opportunities and develop close working relationships with their leaders,Citation19 which is helpful to grasp leaders’ behavioral and emotional intentions,Citation20 and thus enhance voice.Citation21 Hence, our purpose is to examine the mediation effect of perceived ambidextrous leadership and the moderation effect of gender similarity in the relationship between employees’ recognition ability and voice.

This study makes three main contributions to the existing literatures. First, we combine emotion recognition ability with voice, which enriches the antecedents of voice. Although previous research primarily clarifies the mechanism of voice through employees’ constructive and instrumental intentions,Citation5,Citation6 these studies focus on such cognitive factors as status perception, neglecting the roles of emotional factors. According to emotion as social information theory, emotion has the function of social signals. It offers reference information for employees’ behaviors, and can reduce their decision bias, thereby driving employees to make the right decision. Thus, our study extends the antecedents of voice from cognition field to emotion field, and provides new direction for the research on the antecedents of voice.

Second, our findings contribute to the ambidextrous leadership literature. Despite prior studies have examined the antecedents of voice from a single leadership’ perspective (eg, transformational leadership),Citation22 leaders often present different leadership styles over time and space in the managerial practices.Citation23 In addition, compared with other leadership behaviors, ambidextrous leadership behavior is consistent with Chinese traditional thinking- “Yin-Yang Balance”. The extant research rarely focuses on the link among emotion recognition ability, ambidextrous leadership and voice. To fill this research gap, our study integrates ambidextrous leadership research with the research on voice and emotion.

Lastly, we also explore the role of the leader-subordinate gender similarity in the relation between emotion recognition ability and voice, and find that leader-subordinate gender similarity is more likely to promote employees’ voice. Although the existing research holds that leader-subordinate gender combination can significantly influence employees’ attitudes and behaviors,Citation19,Citation20 it still confuses us that what role of leader-subordinate gender similarity plays in the process from “reading facial expressions” to voice, which hinders our understanding of employee behaviors from the perspective of gender. Our study realizes the integration of gender combination and voice, and provides new insights into the antecedents of voice.

Theoretical Background and Hypotheses

Emotion Recognition Ability and Employee Voice

Employee voice refers to employees’ behaviors to informally and voluntarily report problems at work to their leaders, and express their own suggestions to benefit organizational efficiency and transformation.Citation24 In light of its contents, voice can be divided into promotive voice and prohibitive voice. Promotive voice means that employees bring forward constructive suggestions toward process re-engineering and normative innovation to further advance organizational efficiency, emphasizing efficiency improvement while prohibitive voice refers to putting forward their own opinions regard problems impeding organizational efficiency such as inappropriate work flow and unreasonable organizational routines, aims at the improvement of organizational status quo. Since a meta-analysis study showed that promotive and prohibitive voice have a similar triggering mechanism,Citation21 we, in this study, regard voice as a holistic construct.

Emotional recognition ability refers to an individual’s ability to perceive and understand other people’s emotions accurately, and thus guide his/her own behaviors.Citation13 In this study, we focus on employees’ ability to assess and recognize their leaders’ emotions. According to emotion as social information theory, leader’s emotion is an interactive information, and has a social signal function.Citation25 It can be perceived and distinguished by employees through affective reactions process and inferential process.Citation14 We argue that the influence of emotional recognition ability on employee voice is rooted in the transfer process from information reception to information function release. On the one hand, affective reactions process suggests that leaders’ emotional changing can directly affect employees’ emotions,Citation26 which, in turn, leads to employees’ quick recognition and assessment on their leaders’ emotions, engenders interpersonal effects at emotional level through emotional contagion.Citation27 It further makes a recurrence of these emotions in subordinates, and therefore has great influence on subordinate behaviors.Citation28 Employee voice is a typical extra-role behavior with high risk,Citation29 and has strong instrumental intention.Citation5,Citation6 When employees capture the negative emotions of their leaders, they are inclined to keep silence owing to the consideration of psychological risk and resource loss.Citation2 On the other hand, inferential process indicates that employees view leaders’ emotional expressions (emotional information) as their own decision basis.Citation14 Precious studies found that leaders are easy to achieve subordinates’ trust and voice when they show positive emotions.Citation8,Citation30 Besides, a study from Harvard Business Review shows that when it is difficult to distinguish leaders’ emotions, employees will prioritize to button up their mouths for the purpose of resource reservation.Citation10 Thus, we hypothesize:

H1 Employee emotional recognition ability positively influences their voice

The Mediating Role of Perceived Ambidextrous Leadership

In managerial practices, leaders often encounter two opposite tensions or ambidextrous leadership situations.Citation31 It requires leaders to adjust, coordinate and integrate these two contrary and complementary leadership behaviors under a specific situation to benefit from its interaction effects.Citation32 Scholars define these two behaviors as ambidextrous leadership behavior.Citation23,Citation31 Referring to prior studies that tend to regard leadership behavior as a construct regarding subordinate perception,Citation15 we define it as perceived ambidextrous leadership in this study. In contrast to any single leadership behavior, perceived ambidextrous leadership emphasizes leaders’ emotional changes over time and space.Citation23 For instance, adopting different leadership behaviors for employees with different positions,Citation23 or taking different leadership behaviors over time.Citation33 To date, the combinations of perceived ambidextrous leadership are mainly based on three perspectives: opening and closing leadership from the cognitive perspective, transformational and transactional leadership from the conventional perspective, and empowering and directive leadership from the perspective of power.Citation31 The widespread use of transactional leadership in Chinese enterprises,Citation34 coupled with the highest efficacy of transformational leadership in contrast to other single leadership,Citation35 has led to adoption of transactional leadership and transformational leadership in this study.

According to emotion as social information theory, subordinate’s emotional recognition ability affects voice through affective reactions process and inferential process.Citation28 Subordinates draw on leaders’ emotions to judge leaders’ behavioral inclination, and the judgement differs over time and contexts.Citation13 Therefore, we postulate that subordinate’s emotional recognition ability affects voice through perceived ambidextrous leadership. More specifically, subordinates with high emotional recognition ability are more likely to distinguish and evaluate their leaders’ emotions precisely,Citation13 and process leadership behaviors via affective priming,Citation36 so as to appraise the risk of voice.Citation4 For example, when subordinates discern such emotions as concern, support and hope, they are inclined to perceive transformational leadership featuring differential caring and intellectual enlightenment while perceiving transactional leadership featuring rule emphasis and explicit division of labor. Recent studies have indicated that the efficacy of ambidextrous leadership relies on subordinates’ perceptions.Citation23,Citation37 Subordinates’ perceptions are influenced by subordinates’ recognition and assessment on their leaders’ emotions,Citation13 and subordinates have a tendency to appraise the risk of voice through their perceptions.Citation38 By contrast, it is not easy for subordinates with low emotional recognition ability to sense leaders’ emotional changes, which undoubtedly weakens their understanding of leadership behaviors,Citation13 and thus increases their psychological unsafety, and restrain voice.Citation3 Therefore, we hypothesize as follows:

H2 Perceived ambidextrous leadership will mediate the relationship between emotional recognition ability and voice (promotive and prohibitive voice)

Leader-Subordinate Gender Similarity as a Moderator

Gender is a typical demographic characteristic.Citation39,Citation40 Numerous studies have identified that there are role differences between male and female.Citation17,Citation20 For instance, females are supposed to value helping, caring and kindness while males are regarded as confident and independent.Citation41,Citation42 These gender differences are the determinants to comprehensively considering leader-subordinate gender matching when we conduct research on behaviors.Citation19 Specifically, similarity attraction theory suggests that leader-subordinate similarity in the aspect of demographic characteristics, such as gender, age and race, can strengthen their mutual attraction,Citation43 and thus increase the willingness of interaction. Evidence has shown that the similarity attraction effect makes justification for why employees are easy to be attracted by leaders having similarity with themselves.Citation18 Those employees try to figure out their leaders’ behavioral inclination by distinguishing their leaders’ emotional change in hopes of being “insider”.Citation3,Citation44 After surveying the interview process, Graves and PowellCitation45 found that interviewers are more likely to interact with interviewees having the same gender. Frequent leader-subordinate interactions provide employees with more opportunities to convert emotional recognition into behavioral perception.Citation46 In contrast, leader-subordinate gender dissimilarity results in significant differences between them in terms of job role and recognition,Citation47 which is likely to induce working pressure and workplace ostracism,Citation48 and dampens employee enthusiasms of emotional recognition feedback and behavioral perception, thereby prohibitive voice.Citation22 Based on the theoretical and empirical evidence presented above, we argue the following:

H3 When Leader-subordinates gender is consistent, the effect of subordinate’s emotional recognition ability on perceived ambidextrous leadership is stronger, thereby strengthening voice (promotive and prohibitive voice)

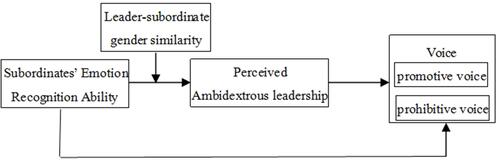

presents the research model suggesting the relationship of all the variables.

Figure 1 Shows the research model of this study. In the research model, we argue that subordinate’ s emotional recognition ability can influence both promotive and prohibitive voice through perceived ambidextrous leadership. Moreover, gender similarity (an leader and his/her subordinates have the same gender) can strengthen the effect of emotional recognition ability on perceived ambidextrous leadership, thereby enhancing promotive and prohibitive voice.

Method

Sample and Procedure

We collected our data from employees and their direct supervisors in four Chinese traditional manufacturing enterprises. At present, Chinese manufacturing enterprises are undergoing transformation and upgrading, therefore employees in manufacturing enterprises have strong voice desires.Citation23 To guarantee the quality of data and reduce common method bias, we handed out the questionnaires in three waves at monthly intervals. One day in advance, one of the authors contacted the general managers or the president of the boards of targeted enterprises, and communicated with department managers about the participant lists and survey sites. The questionnaires were coded before being distributed to facilitate subsequent matching, and the coding principles are confidential for outsider. All surveys were conducted in the form of paper questionnaires, and merely those collected on the spot were adopted in our analyses. In Phase 1, employees were asked to report their demographic characteristics such as gender, age and education, and emotional recognition ability. We collected 302 valid responses after removing 48 responses. In Phase 2, supervisors report their demographic characteristics such as gender, age and education, and employee voice. We obtained 50 direct supervisors of 281 employee (one supervisor with multiple subordinates). One month later, in Phase 3, employees were asked to assess perceived ambidextrous leadership. We finally got 254 employee responses due to the absence of 27 participants. Removing extremely incomplete and invalid responses, we finally gained a sample of 43 supervisors and 182 employees, with a response rate of 71.7%. As for the supervisor sample, 19.0% were female; Supervisor’s age was distributed as follows: 25~35 years (2.4%), 35~45 years (42.9%), 45~60 years (54.7%); For education, 61.9% of the supervisors had a bachelor degree, 21.4% had a master degree, 14.3% had a doctoral degree, and 2.4% had a college degree. Of 182 employees, 60.4% were male. Respondents’ age was distributed as follows: 25 years or below (1.1%), 25~35 years (20.9%), 35~45 years (50.5%), 45~60 years (27.5%). Most of the employees had a bachelor degree (63.7%), 4.9% had high school degree, 15.9% graduated from community college, 15.5% had a master or high degree.

Measures

Participants were asked to report the items on a 5-point scale (1 = totally disagree to 5 = totally agree). We used a 4-item scale to check emotional recognition ability,Citation13 which included items such as “I often capture my leader’s emotions from his/her behaviors”. The Cronbach alpha coefficient for emotional recognition ability was 0.885. According to Rosing, Frese, and Bausch,Citation31 we measured perceived ambidextrous leadership using 12 items scale, with 7 items for transformational leadership and 5 items for transactional leadership. We adopted the interactive term of the means of each measurement.Citation32 The Cronbach alpha coefficient for perceived ambidextrous leadership was 0.868. Employee voice was assessed using a 10-item scale from Liang, Farh, and Farh,Citation24 with 5 items for promotive voice and the other 5 items for prohibitive voice. Sample items were “my subordinates tell the truth on issues that may cost the company even though other people disagree” and “my subordinates positively make suggestions”. The Cronbach alpha coefficient promotive voice and prohibitive voice were 0.874 and 0.926, respectively. Referring to Li and Luo,Citation44 we set leader–subordinate gender similarity as a dummy variable where 0 = the same gender and 1 = different genders. Besides, we controlled age, education, leader-subordinate age similarity and leader-subordinate education similarity following prior studies.Citation44

Results

Descriptive Statistics

displays the means, standard deviations, Pearson correlations for the variables used in our study. presents that subordinate’s emotional recognition ability was positively associated with both promotive voice (r = 0.442, p<0.01) and prohibitive voice (r=0.430, p<0.01), and positively related to perceived ambidextrous leadership (r=0.499, p<0.01). Perceived ambidextrous leadership was positively related to both promotive voice (r=0.376, p<0.01) and prohibitive voice (r=0.288, p<0.01). Besides, gender similarity has no significant relations with other variable. The results are in accordance with our theoretical predictions.

Table 1 Means, Standard Deviations and Correlations of Variables

Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA)

To check the construct validity of the four variables (subordinate’s emotional recognition ability, perceived ambidextrous leadership, promotive voice, and prohibitive voice) in our model, we conducted confirmatory factor analysis with Lisrel 8.7. The results are presented in . As shown in , the four-factor model fit the data well with χ2/df = 2.347, RMSEA = 0.086, SRMR = 0.071, CFI = 0.95, NFI = 0.92. Meanwhile, we contrasted the four-factor model (measurement model) against three-factor, two-factor and one single-factor models, respectively. The results in show that the four-factor model offered better model fit indexes than any other models. Thus, it supported the discriminant validity of the main measures in our study. In addition, we also adopted factor loading, AVE, CR to measure the validity of the key constructs. The results presented that the interval of the factor loadings of emotional recognition ability, perceived ambidextrous leadership, promotive voice, and prohibitive voice were [0.805, 0.882], [0.563, 0.857], [0.781, 0.860] and [0.838, 0.911], respectively, exceeding 0.5; their CR were 0.921, 0.948, 0.910 and 0.944, exceeding 0.7. Besides, all the square root of the AVE of the four variables were over their correlations, supporting convergent validity and discriminant validity. To examine whether there is no response deviation within the questionnaire, we conducted a t-test on both valid and invalid questionnaires. Results showed that there is no significant difference in the aspect of age and education, which indicates that no response deviation exists.

Table 2 Results of Confirmatory Factor Analyses

Hypotheses Testing

We used hierarchical regression analysis method to test the main, mediating and moderating effects in this study. outlines the results. After controlling age, education, leader-subordinate age similarity and leader-subordinate education similarity, the results in M1 presents that subordinate’s emotional recognition ability positively and significantly affects promotive voice (β=0.439, p<0.01). When introducing perceived ambidextrous leadership into the model (M2), we found that perceived ambidextrous leadership has a positive and significant effect on promotive voice (β=0.225, p<0.01) while the impact of subordinate’s emotional recognition ability on promotive voice is weaker (β=0.329, p<0.01). This means that perceived ambidextrous leadership partly mediates the effect of subordinate’s emotional recognition ability on promotive voice. In a similar vein, the results in M3 and M4 indicate that subordinate’s emotional recognition ability positively and significantly influences prohibitive voice (β=0.428, p<0.01) while the influence of perceived ambidextrous leadership on prohibitive voice is not significant (β=0.095, n.s.). This indicates that perceived ambidextrous leadership has no mediating effect in the relationship between subordinate’s emotional recognition ability and prohibitive voice. Therefore, H1 is supported and H2 is partly supported.

Table 3 The Results of Hierarchical Regression Analysis

Since leader-subordinate gender similarity is a dummy variable, to check its moderating role, we tested the mediating effect of perceived ambidextrous leadership under different gender similarity situations referring to Li and Luo.Citation44 The results are displayed in M5-M12. According to M5 and M6, when leaders and subordinates have the same gender, subordinate’s emotional recognition ability positively and significantly affects promotive voice (β=0.366, p<0.01). When perceived ambidextrous leadership was introduced into the model, perceived ambidextrous leadership has a positive and significant effect on promotive voice (β=0.337, p<0.01) while the impact of subordinate’s emotional recognition ability on promotive voice is weaker (β=0.203, p<0.05). This means that perceived ambidextrous leadership partly mediates the effect of subordinate’s emotional recognition ability on promotive voice. Similarly, the results in M9 and M10 indicate that subordinate’s emotional recognition ability and positively and significantly influences prohibitive voice (β=0.344, p<0.01), and perceived ambidextrous leadership has a positive and significant impact on prohibitive voice (β=0.271, p<0.05) when perceived ambidextrous leadership entering the model. Meanwhile, the influence of subordinate’s emotional recognition ability on prohibitive voice is weaker (β=0.209, p<0.05). This indicates that perceived ambidextrous leadership has no mediating effect in the relationship between subordinate’s emotional recognition ability and prohibitive voice.

M7 and M8 present the results when leaders and subordinates have different genders. The results show that subordinate’s emotional recognition ability positively and significantly affects promotive voice (β=0.536, p<0.01). However, when perceived ambidextrous leadership was introduced into the model, the influence of perceived ambidextrous leadership on promoting voice is not significant (β=0.049, n.s.). This means that perceived ambidextrous leadership has no mediating effect in the relationship between subordinate’s emotional recognition ability and promotive voice. In a similar way, according to M11 and M12, subordinate’s emotional recognition ability and positively and significantly influences prohibitive voice (β=0.541, p<0.01). Yet, when perceived ambidextrous leadership enters the model, it has no significant effect on prohibitive voice (β=−0.093, n.s.). This indicates that perceived ambidextrous leadership has no mediating effect in the relationship between subordinate’s emotional recognition ability and prohibitive voice. Together, perceived ambidextrous leadership has a stronger mediating effect when leaders and subordinates have the same gender rather than different genders, supporting H3.

To check the robustness of our conclusions, we further used bootstrapping method to confirm the mediating and moderating effects in the research model. The results are outlined in . The results show that the direct effect of emotional recognition ability on promotive voice is 0.360, with 95% CI of [0.197, 0.524], excluding 0; the indirect effect via perceived ambidextrous leadership is 0.121, with 95% CI of [0.035, 0.239], excluding 0; and the total effect is 0.481, with 95% CI of [0.337, 0.625], excluding 0. This means that perceived ambidextrous leadership partly mediates the relationship between subordinate’s emotional recognition ability and promotive voice. Similarly, we find that the direct effect of emotional recognition ability on prohibitive voice is 0.400, with 95% CI of [0.236, 0.557], excluding 0; the indirect effect via perceived ambidextrous leadership is 0.049, with 95% CI of [−0.037, 0.155], including 0. This means that perceived ambidextrous leadership has no mediating effect in the relationship between subordinate’s emotional recognition ability and prohibitive voice, supporting previous conclusions. In addition, we also used Sobel test to reinforce the robustness of the mediating effect. The results showed that perceived ambidextrous leadership mediates the relationship between emotional recognition ability and promotive voice (2.676, p<0.01), and has no mediating effect between emotional recognition ability and prohibitive voice (1.156, n.s.). H2 is further verified.

Table 4 The Robustness Test on Perceived Ambidextrous Leadership as a Mediator

depicts the results of robustness test on the moderating effect of leader-subordinate gender similarity. Under the situation of leader-subordinate gender congruence, the results indicate that the direct effect of emotional recognition ability on promotive voice is 0.259, with 95% CI of [0.032, 0.487], excluding 0; the indirect effect via perceived ambidextrous leadership is 0.196, with 95% CI of [0.081, 0.358], excluding 0. This means that perceived ambidextrous leadership partly mediates the relationship between subordinate’s emotional recognition ability and promotive voice. Under the situation of leader-subordinate gender incongruence, the results indicate that the direct effect of emotional recognition ability on promotive voice is 0.499, with 95% CI of [0.261, 0.736], excluding 0; the indirect effect via perceived ambidextrous leadership is 0.016, with 95% CI of [−0.088, 0.184], including 0. This means that perceived ambidextrous leadership has no significant mediating effect in the relationship between emotional recognition ability and promotive voice.

Table 5 The Robustness Test on Leader-Subordinate Gender Similarity as a Moderator

Similarly, under the situation of leader-subordinate gender similarity, we find that the direct effect of emotional recognition ability on prohibitive voice is 0.20, with 95% CI of [−0.008, 0.415], including 0; the indirect effect via perceived ambidextrous leadership is 0.156, with 95% CI of [0.018, 0.359], excluding 0. This means that perceived ambidextrous leadership partly mediates the relationship between emotional recognition ability and prohibitive voice. Under the situation of leader-subordinate gender incongruence, the direct effect of emotional recognition ability on prohibitive voice is 0.609, with 95% CI of [0.367, 0.851], excluding 0; the indirect effect via perceived ambidextrous leadership is −0.068, with 95% CI of [−0.205, 0.042], including 0. This means that perceived ambidextrous leadership has no mediating effect on the relationship between emotional recognition ability and prohibitive voice. H3 is further confirmed.

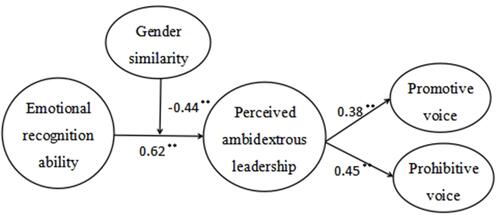

To test the mediation and moderation effect of emotional recognition ability on voice, we construct the structural equation model after multiple revisions according to the T value. As shown in , various indexes provide good fits (χ2=786.22, df = 296, RMSEA = 0.095, CFI = 0.94, NFI = 0.91). Results show that perceived ambidextrous leadership has a mediation effect on the relation between emotional recognition ability and voice, while gender similarity significantly and negatively moderates the relationship between emotional recognition ability and perceived ambidextrous leadership (β=−0.44, p<0.01), that is, leader-subordinate gender similarity is more inclined to reinforce the impact of emotional recognition ability on perceived ambidextrous leadership.

Figure 2 Shows the results of the structure equation model. Various indexes provide good fits (χ2=786.22, df=296, RMSEA=0.095, CFI=0.94, NFI=0.91, **p < 0.01). The results indicate that subordinate’ s emotional recognition ability have a positive impact on perceived ambidextrous leadership (β=0.62, p < 0.01), and thus promote promotive voice (β=0.38, p < 0.01) and prohibitive voice (β=0.45, p < 0.01). In addition, gender similarity negatively affects the first stage mediation effect (β=−0.44, p < 0.01). That is, when an leader and his/her subordinates have the same gender, the mediation effect of perceived ambidextrous leadership will be stronger.

Discussion

Our study has three main theoretical contributions. First, this study integrates subordinate’s emotional recognition ability and employee voice. Previous research tend to demystify the triggering mechanism of employee voice based on employees’ constructive and instrumental intentions,Citation5,Citation6 overlooking the effect of emotion on voice. A survey from Harvard Business Review indicates that “reading facial expressions” is a primary determinant for employee voice.Citation10 Emotion recognition ability reflects subordinates’ recognition and assessment on leaders’ emotions,Citation13 and aroused the concerns of scholars in voice field. The findings of this study show that subordinates with high emotion recognition ability are more likely to conduct voice behaviors. One logical explanation may be that these subordinates are able to make accurate judgement on their leaders’ expectation of voice.Citation22 This study supports emotion as social information theory, that is, leader emotion is a critical interpersonal interaction information, and it can motivate employees’ personal effect emotionally, and thus drive employees to make behavioral decision based on information feedback.Citation25 Additionally, we introduce emotion as social information theory into voice research, which not only advances our understanding of voice, but also provides a new perspective for voice research.

Second, this study sheds light on the mediating role of perceived ambidextrous leadership in the relationship between subordinate’s emotional recognition ability and employee voice. Based on emotion as social information theory, the process of subordinates handling their leaders’ emotional information can affect their behavioral decision-making.Citation14 Study from Harvard Business Review shows that subordinates with high emotion recognition ability are more inclined to evaluate the risk of voice through perceived leadership behaviors.Citation10 Of numerous leadership behaviors, ambidextrous leadership behavior is considered to be with time and space flexibility. Compared with other leadership behaviors, ambidextrous leadership behavior is consistent with Chinese traditional thinking-“Yin-Yang Balance”.Citation23 Hence, this study introduces perceived ambidextrous leadership into the research model regarding subordinate’s emotional recognition ability and employee voice. This study finds that perceived ambidextrous leadership plays a significant mediating role between subordinate’s emotional recognition ability and promotive voice, a no mediating role is found between subordinate’s emotional recognition ability and prohibitive voice. One possible reason is that prohibitive voice may do harm to employees. Because some studies have confirmed that leaders are more likely to show negative emotions when employees point out problems in the current organization or leader.Citation2,Citation49 The conclusion shed light on the application situations of emotion as social information theory. That is, the transmission of emotional information is more likely to promote employees to put forward suggestions for future development, but cannot encourage them to come up with suggestions on improvement toward existing problems. This, on the one hand, sheds light on the specific application situations of emotion as social information theory in the field of organizational behavior, and, on the other hand, expand the voice research based on emotion, and clarifies the difference of the mechanism of different voice, which provides important reference for the further research on voice.

Finally, we investigate the role of leader-subordinate gender similarity between subordinate’s emotional recognition ability and employee voice, and find that leader-subordinate gender congruence can strengthen employee voice. Although prior studies have emphasized the importance of leader-subordinate gender similarity for employee attitudes and behaviors,Citation19,Citation20 it still confuses us that what role of leader-subordinate gender similarity plays in the process from “reading facial expressions” to voice. Drawing on similarity attraction theory, this study finds that leader-subordinate gender congruence can strengthen employee voice. This finding supports Riordan’sCitation43 conclusions that gender congruence can increase mutual attraction and develop close working relationship easily. This conclusion verifies the similarity attraction theory, that is, leader-subordinate gender similarity can strengthen their attraction,Citation18,Citation43 and thus enhance their willingness to interact with each other. This not only provides explanation for voice in terms of gender, but also offers new directions for the antecedents of perceived ambidextrous leadership from the demographic perspective.

Our study also has some practical implications. First, when leaders encourage employees to voice, they should take emotional recognition ability into full consideration, and give priority to the employees with high emotional recognition ability, because those employees are more likely to provide high-quality suggestions. Second, in order to promote employee voice, leaders ought to adopt different leadership styles over time and functions rather than adopt one-size-fits-all approach. For example, transformational leadership for R&D personnel, and transactional leadership for production personnel; transformational leadership in the early stage of a project while transactional leadership in the late stage. The switching of leadership styles can help employees to perceive their leaders’ respect to them, and regard themselves as “insider”. Third, except for such implicit factors as emotional recognition ability, some explicit factors such as gender are as well important for voice and perceiving leader behaviors. Therefore, leaders can pay more attention to those employees having the same gender with them when seeking advice, because those employees are more likely to provide high-quality suggestions.

This study is subject to some limitations. First, although we collected data three-wave collection data from employee and supervisor through three-wave survey, it still belongs to cross-section data. Our data fail to unveil the dynamic evolution of our research model, which is a limitation of this study. We encourage future research to examine the dynamic causal relation among the main variables by collecting data through multiple time points and experience sampling method. Second, demographic indicators provide new perspectives for research on organizational behaviors. This study examines the boundary condition of gender similarity, leaving education similarity and age similarity undeveloped. Therefore, future research should focus on aforementioned similarity indicators. Third, the third limitation of our study is that we merely emphasize the importance of subordinate’s emotional recognition ability. Although previous research has suggested that subordinate’s emotion recognition ability is more likely to enhance employee voice in contrast to leader’s emotion recognition ability.Citation44 However, leader’s emotion recognition ability probably significantly affect voice acceptance because leaders can well judge employees’ intentions of voice if they are able to discern their subordinate’s emotional precisely. Hence, leader’s emotion recognition ability would be a potential direction for voice research.

Conclusions

Drawing on social information theory and similarity attraction theory, we proposed a research model clarifying the mechanism and boundary of subordinate’s emotional recognition ability influencing employee voice. We then tested our research model with data from 182 employee and 43 supervisors using hierarchical regression analysis method and bootstrapping method. The results showed that subordinate’s emotional recognition ability has a significant positive effect on both promotive and prohibitive voice; perceived ambidextrous leadership plays a significant mediating role between subordinate’s emotional recognition ability and promotive voice, a no mediating role is found between subordinate’s emotional recognition ability and prohibitive voice. Additionally, in contrast to leader-subordinate gender dissimilarity, leader-subordinate gender similarity is more likely to strengthen the influence of subordinate’s emotional recognition ability on perceived ambidextrous leadership, thereby motivating voice.

Ethical Statement

The present study adhered to the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the Ethics Committee on Human Experimentation of Shandong University of Finance and Economics. All participants received the first-wave questionnaire in an envelope with an introduction of the study purposes as well as a written informed consent form. We explained that this study welcomed voluntary participation, and complied with the principle of confidentiality, and is only for research purposes. Before response to the first-wave questionnaire, all participants provided informed consent, claimed their understandings of the study purposes and they would like to participate in the study voluntarily.

Acknowledgments

The present study adhered to the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the Ethics Committee on Human Experimentation of Shandong University of Finance and Economics. All participants received the first-wave questionnaire in an envelope with an introduction of the study purposes as well as a written informed consent form. We explained that this study welcomed voluntary participation, and complied with the principle of confidentiality, and is only for research purposes. Before response to the first-wave questionnaire, all participants provided informed consent, claimed their understandings of the study purposes and they would like to participate in the study voluntarily. All authors contributed to the work equally.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interests in this work.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Li C, Liang J, Farh JL. Speaking up when water is murky: an uncertainty-based model linking perceived organizational politics to employee voice. J Manage. 2020;46(3):443–469. doi:10.1177/0149206318798025

- Li J, Barnes CM, Yam KC, Guarana CL, Wang L. Don’t like it when you need it the most: examining the effect of manager ego depletion on managerial voice endorsement. J Organ Behav. 2019;40(8):869–882. doi:10.1002/job.2370

- Li J, Wu LZ, Liu D, Kwan HK, Liu J. Insiders maintain voice: a psychological safety model of organizational politics. Asia Pac J Manag. 2014;31(3):853–874. doi:10.1007/s10490-013-9371-7

- Wu T, Liu Y, Hua C, Lo H, Yeh Y. Too unsafe to voice? Authoritarian leadership and employee voice in Chinese organizations. Asia Pac J Hum Resour. 2020;58(4):527–554. doi:10.1111/1744-7941.12247

- Weiss M, Morrison EW. Speaking up and moving up: how voice can enhance employees’ social status. J Organ Behav. 2019;40(1):5–19. doi:10.1002/job.2262

- Mcclean E, Martin SR, Emich K, Woodruff T. The social consequences of voice: an examination of voice type and gender on status and subsequent leader emergence. Acad Manag Ann. 2018;61(5):1869–1891. doi:10.5465/amj.2016.0148

- Hillebrandt A, Barclay LJ. Comparing integral and incidental emotions: testing insights from emotions as social information theory and attribution theory. J Appl Psychol. 2017;102(5):732–752. doi:10.1037/apl0000174

- Sharma S, Elfenbein HA, Sinha R, Bottom WP. The effects of emotional expressions in negotiation: a meta-analysis and future directions for research. Hum Perform. 2020;33(4):331–353. doi:10.1080/08959285.2020.1783667

- Lam CF, Rees L, Levesque LL, Ornstein S. Shooting from the hip: a habit perspective of voice. Acad Manage Rev. 2018;43(3):470–486. doi:10.5465/amr.2015.0366

- Harvard Business Review. Having a leader with high EQ is the most enviable, envious and hateful; 2018. Available from: https://mp.weixin.qq.com/s/yWmIkpms9PnZYqWRKpYNlA. Accessed December 14, 2021.

- Peralta CF, Saldanha MF, Lopes PN. Emotional expression at work: the effects of strategically expressing anger and positive emotions in the context of ongoing relationships. Hum Relat. 2020;73(11):1471–1503. doi:10.1177/0018726719871995

- Moin MF. The link between perceptions of leader emotion regulation and followers organizational commitment. J Manag Dev. 2018;37(2):178–187. doi:10.1108/jmd-01-2017-0014

- Wong CS, Law KS. The effects of leader and follower emotional intelligence on performance and attitude: an exploratory study. Leadersh Q. 2002;13(3):243–274. doi:10.1016/S1048-9843(02)00099-1

- Van Kleef GA. How emotions regulate social life: the emotions as social information (EASI) model. Curr Dir Psychol Sci. 2009;18(3):184–188. doi:10.1111/j.1467-8721.2009.01633.x

- Meindl JR. The romance of leadership as a follower-centric theory: a social constructionist approach. Leadersh Q. 1995;6(3):329–341. doi:10.1016/1048-9843(95)90012-8

- Pelled LH, Xin KR. Birds of a feather: leader-member demographic similarity and organizational attachment in Mexico. Leadersh Q. 1997;8(4):433–450. doi:10.1016/s1048-9843(97)90023-0

- Ridgeway CL. Gender, status, and leadership. J Curr Soc Issues. 2001;57(4):637–655. doi:10.1111/0022-4537.00233

- Byrne D. The Attraction Paradigm. NY, USA: Ac-ademic Pres; 1971.

- Richard OC, Mckay PF, Garg S, Pustovit S. The impact of supervisor-subordinate racial-ethnic and gender dissimilarity on mentoring quality and turnover intentions: do positive affectivity and communal culture matter? Int J Hum Resour Manag. 2019;30(22):3138–3165. doi:10.1080/09585192.2017.1344288

- Mccoll-Kennedy JR, Anderson RD. Subordinate-manager gender combination and perceived leadership style influence on emotions, self-esteem and organizational commitment. J Bus Res. 2005;58(2):115–125. doi:10.1016/s0148-2963(03)00112-7

- Chamberlin M, Newton DW, Lepine JA. A meta-analysis of voice and its promotive and prohibitive forms: identification of key associations, distinctions, and future research directions. Pers Psychol. 2017;70(1):11–71. doi:10.1111/peps.12185

- Duan J, Li C, Xu Y, Wu CH. Transformational leadership and employee voice behavior: a Pygmalion mechanism. J Organ Behav. 2017;38(5):650–670. doi:10.1002/job.2157

- Li S, Jia R, Seufert JH, Wang X, Luo J. Ambidextrous leadership and radical innovative capability: the moderating role of leader support. Creativity Innov Manag. 2020;29(4):621–633. doi:10.1111/caim.12402

- Liang J, Farh CIC, Farh JL. Psychological antecedents of promotive and prohibitive voice: a two-wave examination. Acad Manag Ann. 2012;55(1):71–92. doi:10.5465/amj.2010.0176

- Van Kleef GA, Homan AC, Finkenauer C, Blaker NM, Heerdink MW. Prosocial norm violations fuel power affordance. J Exp Soc Psychol. 2012;48(4):937–942. doi:10.1016/j.jesp.2012.02.022

- Liu X, Zhang Y, Liu CH. How does leader other-emotion appraisal influence employees? The multilevel dual affective mechanisms. Small Group Res. 2017;48(1):93–114. doi:10.1177/1046496416678663

- Wu TJ, Wu YJ. Innovative work behaviors, employee engagement, and surface acting: a delineation of supervisor-employee emotional contagion effects. Manag Decis. 2019;57(11):3200–3216. doi:10.1108/MD-02-2018-0196

- Van Kleef GA, De Dreu CKW, Manstead ASR. An interpersonal approach to emotion in social decision making: the emotions as social information model. Adv Exp Soc Psychol. 2010;42:45–96. doi:10.1016/s0065-2601(10)42002-x

- Morrison EW, Wheeler-Smith SL, Kamdar D. Speaking up in groups: a cross-level study of group voice climate and voice. J Appl Psychol. 2011;96(1):183–191. doi:10.1037/a0020744

- Ritzenhfer L, Brosi P, Sprrle M, Welpe IM. Leader pride and gratitude differentially impact follower trust. J Manag Psychol. 2017;32(6):445–459. doi:10.1108/jmp-08-2016-0235

- Rosing K, Frese M, Bausch A. Explaining the heterogeneity of the leadership-innovation relationship: ambidextrous leadership. Leadersh Q. 2011;22(5):956–974. doi:10.1016/j.leaqua.2011.07.014

- Luo B, Zheng S, Ji H, Liang L. Ambidextrous leadership and TMT-member ambidextrous behavior: the role of TMT behavioral integration and TMT risk propensity. Int J Hum Resour Manag. 2018;29(2):338–359. doi:10.1080/09585192.2016.1194871

- Lorinkova NM, Pearsall MJ, Sims HP. Examining the differential longitudinal performance of directive versus empowering leadership in teams. Acad Manag Ann. 2013;56(2):573–596. doi:10.5465/amj.2011.0132

- Xu F, Wang X. Transactional leadership and dynamic capabilities: the mediating effect of regulatory focus. Manag Decis. 2019;57(9):2284–2306. doi:10.1108/md-11-2017-1151

- Hoch JE, Bommer WH, Dulebohn JH, Wu D. Do ethical, authentic, and servant leadership explain variance above and beyond transformational leadership? A meta-analysis. J Manage. 2018;44(2):501–529. doi:10.1177/0149206316665461

- Lu J, Zhang Z, Jia M. Does servant leadership affect employees’ emotional labor? A social information-processing perspective. J Bus Ethics. 2019;159(2):507–518. doi:10.1007/s10551-018-3816-3

- Oluwafemi TB, Mitchelmore S, Nikolopoulos K. Leading innovation: empirical evidence for ambidextrous leadership from UK high-tech SMEs. J Bus Res. 2020;119:195–208. doi:10.1016/j.jbusres.2019.10.035

- Ng KY, Van Dyne L, Ang S. Speaking out and speaking up in multicultural settings: a two-study examination of cultural intelligence and voice behavior. Organ Behav Hum Decis Process. 2019;151:150–159. doi:10.1016/j.obhdp.2018.10.005

- Capezio A, Wang L, Restubog SLD, Garcia PRJM, Lu VN. To flatter or to assert? Gendered reactions to Machiavellian leaders. J Bus Ethics. 2017;141(1):1–11. doi:10.1007/s10551-015-2723-0

- Arvate PR, Galilea GW, Todescat I. The queen bee: a myth? The effect of top-level female leadership on subordinate females. Leadersh Q. 2018;29(5):533–548. doi:10.1016/j.leaqua.2018.03.002

- Lanaj K, Hollenbeck JR. Leadership over-emergence in self-managing teams: the role of gender and countervailing biases. Acad Manag Ann. 2015;58(5):1476–1494. doi:10.5465/amj.2013.0303

- Major DA, Morganson VJ, Bolen HM. Predictors of occupational and organizational commitment in information technology: exploring gender differences and similarities. J Bus Psychol. 2013;28(3):301–314. doi:10.1007/s10869-012-9282-5

- Riordan CM. Relational demography within groups: past developments, contradictions, and new directions. Res Pers Hum Resour Manage. 2000;19:131–173. doi:10.1016/s0742-7301(00)19005-x

- Li S, Luo J. Linking emotional appraisal ability congruence of leader-followers with employee voice: the roles of perceived insider status and gender similarity. Acta Psychol Sin. 2020;52(9):1121–1131. doi:10.3724/SP.J.1041.2020.01121

- Graves LM, Powell GN. Sex similarity, quality of the employment interview and recruiters’ evaluation of actual applicants. J Occup Organ Psychol. 1996;69(3):243–261. doi:10.1111/j.2044-8325.1996.tb00613.x

- Matta F, Van Dyne L. Understanding the disparate behavioral consequences of LMX differentiation: the role of social comparison emotions. Acad Manage Rev. 2020;45(1):154–180. doi:10.5465/amr.2016.0264

- Van Gils S, Van Quaquebeke N, Borkowski J, Van Knippenberg D. Respectful leadership: reducing performance challenges posed by leader role incongruence and gender dissimilarity. Hum Relat. 2018;71(12):1590–1610. doi:10.1177/0018726718754992

- Qian J, Yang F, Wang B, Huang C, Song B. When workplace ostracism leads to burnout: the roles of job self-determination and future time orientation. Int J Hum Resour Manag. 2019;30(17):2465–2481. doi:10.1080/09585192.2017.1326395

- Burris ER. The risks and rewards of speaking up: managerial responses to employee voice. Acad Manag Ann. 2012;55(4):851–875. doi:10.5465/amj.2010.0562