Abstract

Chagas disease caused by Trypanosoma cruzi is an important public health problem in Latin America. Dogs are considered a risk factor for human Chagas disease, a sentinel for T. cruzi infection in endemic regions and an animal model to study pathological aspects of the disease. The potential use of dogs as indicators of human cardiac pathogenicity of local T. cruzi strains has been studied insufficiently. We studied electrocardiographic (EKG) and echocardiographic (ECG) alteration frequencies observed in an open population of dogs in Malinalco, Mexico, and determined if such frequencies were statistically associated with T. cruzi infection in dogs. Animals (n = 139) were clinically examined and owners were asked to answer a questionnaire about dogs’ living conditions. Two commercial serological tests (IHA, ELISA) were conducted to detect anti-T. cruzi serum antibodies. Significant differences between seropositive and seronegative animals in cardiomyopathic frequencies were detected through EKG and ECG (P < 0.05). Thirty dogs (21.58%) were serologically positive to anti-T. cruzi antibodies (to ELISA and IHA assays), of which nine (30%) had EKG and/or ECG alterations. From the remaining 104 (78.42%) seronegative animals, five (4.5%) had EKG and/or ECG abnormalities. Our data support the hypothesis that most EKG and ECG alterations found in dogs from Malinalco could be associated with T. cruzi infection. Considering the dog as a sentinel and as an animal model for Chagas disease in humans, our findings suggest that the T. cruzi strains circulating in Malinalco have the potential to produce cardiomyopathies in infected humans.

Introduction

Chagas disease is caused by Trypanosoma cruzi and is transmitted by a hematophagous insect vector (“kissing bug”) of the Reduviidae family. Approximately 10 million people are infected with T. cruzi in 19 countries in Latin America and ∼50,000,000 people live at risk of infection.Citation1 In Mexico, 1.6–5.8 million people may be infected with T. cruzi.Citation2–Citation5 Our group has been studying Chagas disease in the State of Mexico, located under the Tropic of Cancer, where most critical transmission areas in Mexico are located.Citation4,Citation5 In a previous study we reported T. cruzi prevalences of 7.1% and 21% for humans and dogs, respectively,Citation6 and more recently we have described an epidemiologic study using dogs and triatomines to assess parasite circulation in the Tejupilco municipality.Citation7 Malinalco is a town located in the south-center region of the State of Mexico, from which no previous reports on T. cruzi circulation have been published. However, it is a neighboring area of Tejuplico municipality and shares geographic characteristics with this region. It is also a neighbor of the State of Morelos, where T. cruzi circulation has been previously reported,Citation6–Citation10 and from Zumpahuacan, from which a pathogenic T. cruzi strain has been previously reported and characterized.Citation11 In the latter study we used dogs as a model to compare the pathogenicity of a regional T. cruzi strain vs a reference strain (Sylvio X-10), and described clinical (electrocardiographic and echocardiographic) and pathological (macroscopic and microscopic) cardiac alterations caused by these strains and found that, although the two strains were pathogenic, they had differences in virulence, as reported for other strains.Citation12 Therefore, epidemiologic studies of Chagas disease in a specific geographical area should consider the pathogenicity of the regional circulating T. cruzi strains. Dogs are considered an excellent animal model to study Chagas disease since it mimics the clinical and pathological signs of the disease in humans.Citation13,Citation14 Accordingly, the objectives of the present study were: first, to use the house-owned dogs from Malinalco to evaluate the feasibility to use them as sentinels to determine prevalence of T. cruzi infection in humans in the city and, second, to evaluate the pathogenicity of the circulating strains with an electrocardiographical and echocardiographical epidemiologic study.

Animals, materials, and methods

Study area

Malinalco () is located in the south-eastern area of the State of Mexico (between 19°01′58″ to 18°45′18″ N and 99°35′24″ to 99°25′34″ W) with an average altitude of 1750 m. It has seasonal climate variations (dry season November–May and rainy season June–October) with an average annual temperature of 20°C. According to the 2005 National Census Program,Citation15 Malinalco has a population of 22,970 and the main economic activities are agriculture, livestock production, and tourism. According to the 2008 State of Mexico Rabies Vaccination Program, Malinalco has a total population of 2160 house dogs.

Animals

House-owned dogs (n = 139) from Malinalco were studied to assess the prevalence of T. cruzi infection in these animals and to study the impact of the infection on dogs’ heart conditions. The sample size was calculated with free software “Sample Size Calculator Software”,Citation16 with the following parameters: 95% confidence interval, 5% error, a universe of 2160 house dogs, and 10% estimated prevalence of T. cruzi infection. All dogs were evaluated serologically for anti-T. cruzi antibodies and electrocardiographically and echocardio-graphically for heart health. Dogs were included in the study after personalized owners-informed invitation and consent to participate in the study. Owners were asked to answer a brief questionnaire to gather information regarding dogs’ breed, weight, sex, age, health status and habits to access the house, existence of triatomines (kissing bug) within or around the house, and pesticide spraying frequency, if any. Additionally, all dogs had to go through a veterinarian physical examination to evaluate their general health status.

Sample collection

Dogs were handled in the presence of their owners to keep stress and risk to animals and handlers at a minimum. Blood samples (7 mL) were obtained by puncture of the cephalic vein and collected into tubes (Vacutainer®, Becton-Dickinson, Mexico, DF, Mexico), sera was obtained by centrifugation at 2000 rpm for 20 minutes, and stored at −20°C until use. Sera samples were analyzed for anti-T. cruzi antibodies by IHA (Polychaco, Laboratorio-Lemos SRL, Buenos Aires, Argentina) (with 98% sensitivity and 99% specificity according to the manufacturer’s specifications) and ELISA (Laboratorio-Lemos SRL, Buenos Aires, Argentina) Chagas diagnostic kits (with 100% sensitivity and 100% specificity, according to the manufacturer’s specifications). All assays were performed according to manufacturer’s instructions, except that the HRP-labeled, anti-human IgG antibody in the ELISA kit was replaced with HRP-labeled anti-dog IgG (Koma Biotech, Seoul, Korea) as a secondary antibody.Citation11 The cut-off value for IHA was set at ≥1:16 serum dilution and for ELISA at 0.129 OD450 nm +0.1 (or +2-SD). Samples were considered positive when reactive for both assays.

Electrocardiography (EKG)

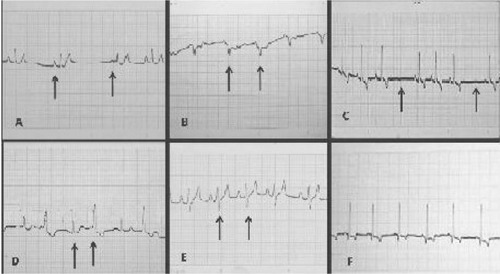

Changes in cardiac rhythm and electrical conduction were monitored in all dogs with an EK-8 electrocardiographic machine (Burdick Stylus, Milton, WI), set at 120V, 60 Hz, 20 amps, and 25 watts, and six leads were considered at 25 mm/second at 1 mV, standardized to 1 cm ().

Echocardiography (ECG)

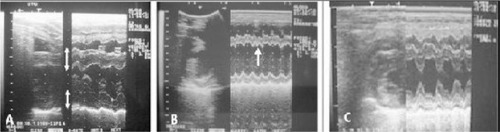

An ultrasonograph machine (SSD-500, 5 MHz probe; Aloka, Wallingford, CT), with two-dimensional and M-mode functions was used to analyze ventricular function through short-axis images and right parasternal views ().

Figure 3 BM-mode echocardiography of seropositive dogs to Trypanosoma cruzi, in the Malinalco village, State of Mexico. (A) Increased thickness of the interventricular septum and left ventricular wall; (B) asynchronic interventricular septum motility; (C) normal.

Statistical analysis was conducted through contingency tables and using EPIDAT (v 3.1, 2006, OPS/OMS). Where the immunologic outcome (seropositive or seronegative) was contrasted vs the following variables: EKG (cardiomyopathy or normal), ECG (cardiomyopathy or normal), age (<1, 1–2.9, 3–6.9 or >7 years old), housing (indoor or outdoor), sex (male or female), and weight (,<10 or >10 kg). Statistical analysis included odd ratios (OR), prevalence ratio (PR) and Chi square (χ2), with 95% confidence intervals and P < 0.05.

Results

Dogs’ physical examination showed that all animals were apparently healthy. However, the study found 21.58% (30/139) dogs seropositive to anti-T. cruzi IgG antibodies through IHA and ELISA serology tests.

Differences in the frequency of electrocardiographic and echocardiographic abnormalities were found (P < 0.05) between seropositive and seronegative animals, where 9/30 (30%) and 5/109 (4.5%) dogs presented electrocardiographic abnormalities (; ), and 10/30 (33.3%) and 17/109 (15.5%) dogs resulted with echocardiographic abnormalities for seropositive and seronegative animals, respectively (; ). The main abnormalities found in seropositive dogs with echocardiography were: right ventricle dilation in 13.3% (4/30), increased motility and or asynchrony of the interventricular septum in 13.3% (4/30), left ventricle dilated in 13.3% (4/30), and left ventricular wall thickened in 26.6% (8/30). Echocardiographic abnormalities from seronegative dogs were similar to those found in seropositive dogs but at a lower frequency (; ).

Table 1 Electrocardiographic alterations found in Trypanosoma cruzi seropositive and seronegative dogs from Malinalco village, State of Mexico

Table 2 Echocardiographic alterations found in Trypanosoma cruzi seropositive and seronegative dogs from Malinalco village, State of Mexico

Factors such as age, housing conditions, weight, and sex were examined for association with seropositivity (–). No statistical differences could be found for these variables, however some tendencies could be observed in the age of the animals and outdoor housing conditions, which were associated with larger prevalences, suggesting that these variables could be considered as possible risk factors in future studies which should be performed at a larger scale. Overall, a larger proportion of female animals were sampled (86:53 female/male), and a larger proportion (25.5%) of this group was seropositive when compared to males (15.0%). However, no statistical difference was found. The analysis of the influence of dogs’ breed on seropositivity prevalence was not possible because the sample size was not large enough due to the diversity of breeds found in the study.

Table 3 Age associated with seropositivity to T. cruzi in dogs from Malinalco village, State of Mexico

Table 6 Sex associated to seropositivity to Trypanosoma cruzi in dogs from Malinalco village, State of Mexico

Discussion

The use of dogs as sentinels to assess human risk of infection was first proposed by Gürtler and colleagues.Citation13 More recently, our group demonstrated that T. cruzi is found in humans, dogs, and triatomines and found a direct correlation of anti-T. cruzi sero-prevalence between humans (7%) and dogs (21%) in the southern region of the State of Mexico.Citation6–Citation8 We have also previously demonstrated that regionally circulating T. cruzi strains are pathogenic for dogs, either after natural or experimental infections.Citation11 Here we report a 21.58% seroprevalence anti-T. cruzi in dogs found in Malinalco (a tourist town in a municipality of the southern region of the State of Mexico, with no previous seroprevalence reports). These findings agree with our previous reports in the southern region of the State of Mexico, and considering climatic, geographic, and ecological similarities of the regions studied, this outcome is not surprising. Here we also report the association of seroprevalence of IgG anti-T. cruzi antibodies found in dogs from Malinalco and the occurrence of electrocardiographic and echocardiographic abnormalities in this species. We also analyzed some variables that have been associated with the seroprevalence of dogs to T. cruzi, as risk factors; such as age, weight, sex, and housing.

Through EKG and ECG we found that T. cruzi seropositive animals develop cardiac abnormalities with higher frequencies than seronegative dogs. This finding was expected, since it has been previously demonstrated by us and others that this parasite induces cardiac abnormalities in dogs, and that some T. cruzi strains found in the south of the State of Mexico are cardiopathogenic for dogs.Citation7,Citation11 It is of general knowledge that cardiomyopathies can be found through EKG and ECG among apparently healthy, uninfected, open populations of dogs. The type and frequencies of these pathologies may vary according to the breed and age.Citation17,Citation18 Here we report electrocardiographic and echocardiographic alterations in an open population of dogs and analyzed their relationship with the seroprevalence of IgG antibodies against T. cruzi. The prevalence of cardiac abnormalities among house dogs living in Malinalco was 10.07%. However, as predicted, cardiomyopathic frequencies were different (P < 0.05) among anti-T. cruzi seropositive (30%) and seronegative (4.5%) animals ( and ). These findings support our previous report in which we concluded that T. cruzi strains circulating in the southern region of the State of Mexico are pathogenic to dogs.Citation11

Dogs have been considered sentinels for T. cruzi circulation in endemic areas,Citation12 and it has also been proposed as a model for Chagas disease since infected dogs mimic some of the signs and pathologies seen in humans,Citation12–Citation14 therefore we considered it interesting to evaluate the dog as a sentinel, so that in future it could be used as a tool to estimate human risk of developing cardiomyopathies derived from infection with local T. cruzi strains in different endemic regions. For instance, in a previous study, we reported a correlation of 1:3 between human (7.1%) and dog (21%) anti-T. cruzi seroprevalences in the southern region of the State of Mexico.Citation6 Therefore, assuming that the same correlation exists in cardiac abnormalities due to T. cruzi infection, we could predict that from an estimated population of 2160 house dogs and 22,970 people living in Malinalco,Citation15 there should be around 444 and 1608 individuals infected, and 113 and 410, individuals with cardiomyopathies derived from T. cruzi infection for dogs and humans, respectively. This estimate is merely speculative and further research is necessary to obtain conclusive evidence, however this approach could be helpful as an indirect method to estimate epidemiologic information necessary for the design of official public health programs.

When we analyzed some variables that could be participating as risk factors of infection, we were able to find some tendencies of association but not statistically signification correlations. Previous studies have reported age as an accumulative risk factor of infection.Citation19–Citation21 In this study we observed a strong tendency of age to be associated to seroprevalence, however no statistical significance was found (P > 0.05) (). Future studies should include a larger sample size, to better estimate age as a risk factor. Another factor that has been reported as a risk factor is dog housing (indoor–outdoor). In this study we were not able to demonstrate that housing (indoor vs outdoor), is a risk factor in this endemic region. But, we observed that most owned dogs involved in the present study (77.69%), are regularly kept outside the house or are able to go in and out at their own will; all of these dogs were considered outdoor animals, and the animals that were kept mostly inside the house were included in the indoor group; the prevalences were 6.5% and 25.92% for indoor and outdoor groups, respectively (). A tendency to have a lower seroprevalence was observed in dogs that were maintained exclusively indoors when compared to outdoor dogs. Most likely a larger sample size is necessary to demonstrate the differences associated with the housing risk factor. On the other hand, other variables analyzed, such as dog weight and sex, do not seem to play important roles in the likelihood of infection ( and ).

Table 4 Housing associated to seropositivity to Trypanosoma cruzi in dogs from Malinalco village, State of Mexico

Table 5 Body weight associated to seropositivity to Trypanosoma cruzi in dogs from Malinalco village, State of Mexico

We conclude that a relatively high anti-T. cruzi antibody seroprevalence in house-owned dogs from Malinalco village is related to elevated frequencies of electrocardiographic and echocardiographic abnormalities. Further studies should be conducted to fully evaluate dogs as sentinels of infection-induced, cardiac abnormalities in humans.

Furthermore, our observations emphasize the need of state health agencies to conduct more aggressive, epidemiologic surveillance programs and implement vector control strategies in the State of Mexico, since the seroprevalence found in dogs suggests that there is a latent risk of human infection in Malinalco.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grants of (FE039/2008) SIyEA of Universidad Autónoma del Estado de México.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- SchofieldCJJeannineJSalvatellaRThe future of Chagas disease controlTrends Parasitol20062258358817049308

- Velasco-CastrejónOGuzmán-BrachoCImportance of Chagas disease in MexicoRev Latinoam Microbiol198628275283 Spanish3108985

- Velazco-CastrejónOChagas disease seroepidemiology in MexicoMexico’s Public Health Journal199234186196 Spanish

- Guzmán-BrachoCEpidemiology of Chagas disease in Mexico: an updateTrends Parasitol20011737237611685897

- Cruz-ReyesAPickering-LópezJMChagas disease in México: an analysis of geographical distribution during the past 76 years – a reviewMem Inst Oswaldo Cruz2006101345354

- Estrada-FrancoJGVandanajayBDíaz-AlbiterHHuman Trypanosoma cruzi infection and seropositivity in dogs, MéxicoEmerg Infect Dis20061262463016704811

- Barbabosa-PliegoACamposPOlivaresDPrevalence of Trypanosoma cruzi in dogs (Canis familiaris) and triatomines during 2008 in a sanitary region of the State of Mexico, MexicoVector Borne Zoonotic Dis20111115115620575648

- Medina-TorresIVázquez-ChagoyánJCRodríguez-VivasRIMontes de Oca-JiménezRRisk factors associated with triatomines and its infection with Trypanosoma cruzi in rural communities from the southern region of the State of Mexico, MexicoAm J Trop Med Hyg201082495420064995

- Cortés JiménezMNogueda TorresBAlejandre AguilarRIsita TorneliLRamírez MorenoEFrequency of triatomines infected with Trypanosoma cruzi collected in Cuernavaca city, Morelos, México RevLatinoam Microbiol199638115119

- BautistaNLGarcía de la TorreGSde Haro-ArteagaISalazar-ShettinoPMImportance of Triatoma pallidipennis (Hemiptera: Rediviidae) as a vector of Trypanosoma cruzi (Kinetoplasmida: Trypanosomatidae) in the state of Morelos, Mexico, and possible ecotypesJ Med Entomol19993623323510337089

- Barbabosa-PliegoADíaz-AlbiterHMOchoa-GarcíaLTrypanosoma cruzi circulating in the southern region of the State of Mexico (Zumpahuacan) are pathogenic: a dog modelAm J Trop Med Hyg20098139039519706902

- AndradeZAThe canine model of Chagas diseaseMem Inst Oswaldo Cruz1984797783

- GürtlerRESolardNDLauricelaMAHaedoMDynamic of transmission of Trypanosoma cruzi in a rural area of Argentina. III Persistence of Tcruzi parasitemia among canine reservoirs in a two-years followupRev Inst Med Trop Sao Paulo1986282132193105037

- CaliariMVMachadoRLanaMQuantitative analysis of cardiac lesion in chronic canine Chagasic cardiomiopathyRev Inst Med Trop Sao Paulo20024427327812436168

- INEGI2005National Institute of Statistic, Geography and Informatics (INEGI) Available at: http://www.inegi.org.mxAccessed August 11, 2011

- Roasft. RoasoftSample size calculatorRaosoft, Inc.2004 Available at: http://www.raosoft.com/samplesize.htmlAccessed January 28, 2008

- Dukes-McEwanJBorgarelliMTidholmAVollmarACHäggströmJProposed guidelines for the diagnosis of canine idiopathic dilated cardiomyopathyJ Vet Cardiol20035719

- OyamaMASissonDDSolterPFProspective screening for occult cardiomyopathy in dogs by measurement of plasma atrial natriuretic peptide, B-type natriuretic peptide, and cardiac troponin-I concentrationsAm J Vet Res200768424717199417

- GürtlerRECecereMCLauricellaMAIncidence of Trypanosoma cruzi infection among children following domestic reinfestation after insecticide spraying in rural northwestern ArgentinaAm J Trop Med Hyg2005739510316014842

- DiosquePPadillaAMCiminoROChagas disease in rural areas of Chaco Province, Argentina: epidemiologic survey in humans, reservoirs, and vectorsAm J Trop Med Hyg20047159059315569789

- Pascon daEJPPereiraNGSousaGMJuniorDPCamachoAAClinical characterization of chagasic cardiomyopathy in dogsPesq Vet Bras201030115120