Abstract

Background

The aim of this systematic review was to determine the effectiveness of Internet interventions in promoting smoking cessation among adult tobacco users relative to other forms of intervention recommended in treatment guidelines.

Methods

This review followed Cochrane Collaboration guidelines for systematic reviews. Combinations of “Internet,” “web-based,” and “smoking cessation intervention” and related keywords were used in both automated and manual searches. We included randomized trials published from January 1990 through to April 2015. A modified version of the Cochrane risk of bias assessment tool was used. We calculated risk ratios (RRs) for each study. Meta-analysis was conducted using random-effects method to pool RRs. Presentation of results follows the PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses) guidelines.

Results

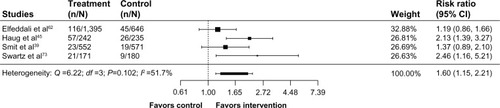

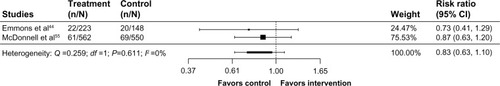

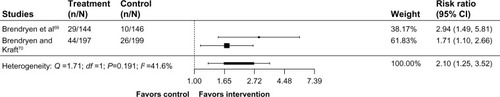

Forty randomized trials involving 98,530 participants were included. Most trials had a low risk of bias in most domains. Pooled results comparing Internet interventions to assessment-only/waitlist control were significant (RR 1.60, 95% confidence interval [CI] 1.15–2.21, I2=51.7%; four studies). Pooled results of largely static Internet interventions compared to print materials were not significant (RR 0.83, 95% CI 0.63–1.10, I2=0%; two studies), whereas comparisons of interactive Internet interventions to print materials were significant (RR 2.10, 95% CI 1.25–3.52, I2=41.6%; two studies). No significant effects were observed in pooled results of Internet interventions compared to face-to-face counseling (RR 1.35, 95% CI 0.97–1.87, I2=0%; four studies) or to telephone counseling (RR 0.95, 95% CI 0.79–1.13, I2=0%; two studies). The majority of trials compared different Internet interventions; pooled results from 15 such trials (24 comparisons) found a significant effect in favor of experimental Internet interventions (RR 1.16, 95% CI 1.03–1.31, I2=76.7%).

Conclusion

Internet interventions are superior to other broad reach cessation interventions (ie, print materials), equivalent to other currently recommended treatment modes (telephone and in-person counseling), and they have an important role to play in the arsenal of tobacco-dependence treatments.

Background

Health care around the globe is being transformed to deliver care and services in ways that are less costly and more convenient for both providers and patients.Citation1,Citation2 At the center of this transformation are digital health interventions facilitated by the Internet. Internet interventions can reach large numbers of people who may not otherwise access preventive and clinical health care services and engage them with convenient, accessible, multimedia interventions that can be used flexibly, often anonymously, for as long as the user desires.Citation3 Personalized and individually tailored treatment can be delivered via the Internet in ways that mimic many of the aspects of face-to-face clinical interventions.Citation4 Importantly, whereas ongoing clinical intervention within the health care delivery system is often prohibitively expensive and unsustainable, treatment via Internet interventions is scalable, sustainable, and cost-efficient.Citation5

Internet interventions for tobacco cessation may have an important role to play in improving individual, community, and population health. Tobacco use remains the leading cause of preventable death worldwide.Citation6 It is widely accepted that comprehensive tobacco control measures are needed to reduce tobacco use, including efforts to provide tobacco-dependence treatments on a population-wide basis.Citation7 Cessation treatment guidelines recommend screening for tobacco use in health care settings, behavioral counseling delivered via individual, group, or telephone counseling, and pharmacotherapy.Citation8–Citation10 However, these approaches may not reach a majority of smokers. For example, in the USA, only 20.9% of tobacco users are counseled about tobacco use and only 7.6% are advised to use pharmacotherapy by a health care provider.Citation11 Residents throughout the USA and Canada have access to quitline services, but uptake is <10% of smokers each year.Citation12 The use of cessation medication widely varies even when it is free or inexpensive to access.Citation13–Citation16 To curb the tobacco use epidemic and avert the enormous toll projected from tobacco, additional interventions are needed to complement the existing arsenal of tobacco treatment strategies.

Internet interventions for smoking cessation are currently offered around the world by a broad range of national, regional, and local government entities, as well as commercial and nonprofit organizations.Citation17 Hundreds of thousands of smokers register on web-based cessation programs each year, whether through programs offered by quitlines,Citation18 employers, and health plans,Citation19 or on publicly available, high-volume web-based cessation programs around the globe.Citation20–Citation22 The Internet is the first place many people turn to for information and assistance with health-related concerns,Citation23 and it has been estimated that millions of smokers look online for quit smoking assistance each year.Citation24,Citation25

However, despite the provision of Internet cessation interventions by a broad range of stakeholders around the globe, and the demonstrated uptake of Internet cessation interventions among smokers, tobacco-dependence treatment guidelines have noted their promise but have stopped short of including them as a recommended treatment strategy, instead calling for more research on their effectiveness.Citation8–Citation10,Citation26 A recent review of reviews conducted by Patnode et alCitation9 considered evidence from six systematic reviews, drawing primarily on the most recent 2013 review by Civljak et al.Citation27 They concluded that Internet-based behavioral interventions for smoking cessation have high potential applicability to primary care within the USA but that evidence on the use of Internet interventions was limited and not definitive.

The objective of this systematic review was to determine the effectiveness of Internet interventions in promoting smoking cessation among adult tobacco users, considering the numerous studies published since the 2013 review by Civljak et al.Citation27 We were particularly interested in studies comparing Internet interventions to other forms of treatment that have been recommended in treatment guidelines to better understand whether there is a role in comprehensive tobacco control for Internet-based approaches. We examined whether Internet interventions are more effective in promoting abstinence compared to: 1) assessment-only/waitlist control, 2) print materials, 3) face-to-face counseling, 4) telephone counseling, and 5) static/generic websites.

Methods

Design

This study is a systematic review of randomized controlled trials following Cochrane methodological guidance.Citation28 The PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses) checklist and flow diagram are used as aids in the reporting of this systematic review. A structured approach was used to build the eligibility criteria.Citation29

Eligibility criteria

Participants: We included studies conducted with adults aged ≥18 years regardless of sex; studies with children were included, provided that outcome data for adults were reported separately. We included studies that involved participants who were current smokers at the outset of the trial. We included studies with recent quitters as long as abstinence was reported for current smokers. Smokeless tobacco studies were excluded.

Interventions: For the purposes of this review and borrowing from published definitions, we define Internet smoking cessation interventions as being primarily composed of directive information and support services delivered via the Internet with the goal of supporting the user in trying to quit tobacco.Citation30 Internet interventions are largely self-guided, at least partially automated, and take advantage of the interactive nature of the Internet.Citation31 The basis of such programs is typically behaviorally or cognitive-behaviorally based treatments that have been operationalized and transformed for delivery via the Internet.Citation32 For the purposes of this review, we exclude mHealth interventions, such as text messaging or interventions delivered solely through a mobile device.Citation33 mHealth interventions were excluded in order to decrease heterogeneity in the interventions assessed in this review and to be consistent with previous reviews of Internet interventions. Nonetheless, excluding interventions delivered solely through a mobile device does not exclude Internet smoking cessation interventions that may have been accessed through a mobile web browser.

Comparisons: There were no exclusion criteria for comparison interventions.

Outcomes: Studies that reported abstinence from smoking with at least a 1-month follow-up as the primary outcome were included. Measures of abstinence included 7-day point prevalence abstinence, 30-day point prevalence abstinence, repeated point abstinence, continuous abstinence, sustained abstinence, and prolonged abstinence. Self-reported and biochemically verified metrics of abstinence were included.

Report characteristics and study design: We included English-language quantitative studies that employed a randomized design published since 1990. We excluded cohort studies, qualitative studies, editorials, letters, and commentaries, studies where we could not identify a full text, and articles that did not report the minimum information required.

Information sources and search strategy

We employed a mixed automated and manual search strategy. We conducted a comprehensive literature search using the following bibliographic databases: PubMed, CINAHL Plus with Full Text, Cochrane Library, PsycINFO, EMBASE, Web of Science, Communication and Mass Media Complete, Global Health, Grey Literature Report, IEEE Xplore, and Google Scholar. We used a combination of the constructs “Internet,” “web-based,” and “smoking cessation intervention” and related keywords to ensure broad coverage of published studies. Search terms were intentionally broad to ensure that all relevant articles would be captured (Supplementary materials, Appendix 1). Our search covered English language papers published between January 1990 and April 2015. We also reviewed the reference lists of included manuscripts and previous systematic reviews. All other databases were searched with free text terms reflecting inclusion criteria. Citations were compiled in EndNote (EndNote Version X6; Thomson Reuters, Philadelphia, PA, USA) and imported and de-duplicated in EPPI-Reviewer 4.0 (University College London, Institute of Education, University of London, UK).Citation34

Study selection

The title and abstract of identified citations were screened for eligibility by two reviewers. Items were included at this stage if they appeared to meet inclusion criteria based on information in the title and abstract and were excluded only if clearly ineligible. When only the study title was available, the presence of keywords in the title related to “an Internet intervention” and “smoking cessation” warranted full-text review. Next, we obtained the full texts of citations considered as potentially eligible. Two reviewers independently screened the full text for eligibility using a standardized and pilot-tested screening process. Discrepancies were resolved by the team. Finally, reference lists of previous reviews and recent publications were checked.

Data collection process and data items

Eligible studies were coded to capture both substantive and methodological characteristics. The coding focused on the following features of the studies: identifying information, funding source, design, aims and objectives, variables related to the characteristics of participants, the nature of the intervention and its implementation, the nature of the comparison condition(s) and their implementation, analytical methods, follow-up duration and rates, and outcome measurements. In addition, we extracted information about strategies used to promote engagement/adherence in accordance with the study by Alkhaldi et al.Citation35 We included selected items from the CONSORT-EHEALTH checklist relevant to the reporting of eHealth trialsCitation36 (eg, intervention access, level of human involvement, and engagement strategies).

The data abstraction form was pilot tested on a purposive sample of eligible studies.Citation22,Citation37–Citation41 Reviewers were retrained on coding items that showed discrepancies during this process, and the coding scheme was adapted. This process was repeated until a high level of consistency was achieved. The remaining studies were coded by a single reviewer and reviewed by a second reviewer. Discrepancies were resolved by group discussion.

Risk of bias in individual studies

We used the Cochrane Collaboration tool for assessing the risk of bias.Citation28 As in the systematic review by Mathieu et al,Citation42 we elected not to consider reporting bias since few studies prospectively registered their protocols. Following Civljak et al,Citation27 we did not assess participant blinding due to the inherent difficulty in blinding participants to behavioral interventions. Reviewers’ judgments regarding the risk of bias for each criterion were rated as low, high, or unclear. We computed graphic representations of potential bias within and across studies using EPPI-Reviewer 4.0 software.

Data analysis

The majority of studies reported cessation outcomes at multiple endpoints using multiple metrics (eg, 7-day abstinence, 30-day abstinence). When the authors specified a primary outcome (eg, used for power analyses), we selected it for analysis; if a primary outcome was not explicitly stated, we included the longest endpoint and most conservative metric of abstinence. We conducted an intention-to-treat (ITT) analysis, including all participants as randomized in the denominator; individuals lost to follow-up were counted as smokers. Abstinence rates were summarized as risk ratios (RRs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) using the ITT principle, which were calculated as: ([number of quitters: intervention arm]/[number randomized: intervention arm])/([number of quitters: control arm]/[number randomized: control arm]). We display descriptive data alongside RRs with 95% CIs in forest plots.

We assessed statistical heterogeneity using the I2 statistic, which assesses the proportion of the variation between studies due to heterogeneity rather than to chance.Citation43 I2 ranges from 0% to 100%, with 0% indicating no observed heterogeneity and larger values showing increasing heterogeneity. The importance of the observed value of I2 depends on the magnitude and direction of effects as well as the strength of evidence for heterogeneity (eg, P-value from the chi-squared test). I2 values of 25%, 50%, and 75% approximately correspond to low, moderate, and high levels of statistical heterogeneity, respectively.Citation43

We judged random-effects meta-analysis to be appropriate for all five comparisons of interest. In each of these comparisons, we pooled the weighted average of RRs using a random-effects model and 95% CI. To be conservative, we excluded trials with less than a 3-month follow-up, those that were feasibility studies, and those with very low follow-up rates.

Results

Study selection

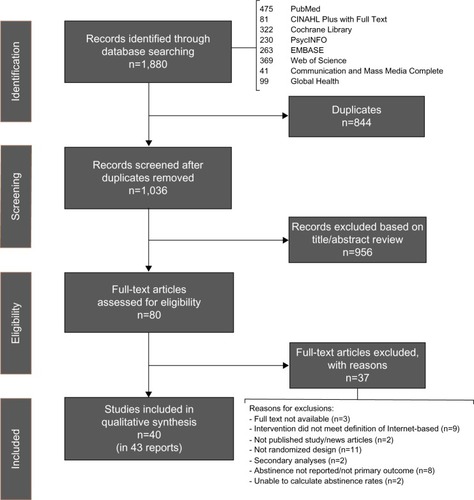

shows the study flow. A total of 80 records were reviewed for eligibility, and 37 were excluded (Supplementary materials, Appendix 2) for the following reasons: full text was not available (n=3), intervention did not meet the definition of “Internet-based” (n=9), record was not a published study (n=2), not a randomized design (n=11), secondary analysis of outcome data presented elsewhere (n=2), smoking outcomes not reported (n=8), and we were unable to calculate abstinence rates using available data (n=2). Forty individual trials with a total of 98,530 participants were included (described in 43 reports) and are listed in Supplementary materials (Appendix 3).

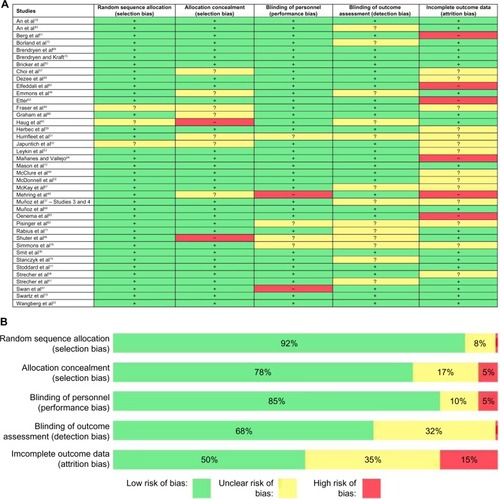

Risk of bias within and across studies

Overall, the studies included in this review had low risk of bias in most or all areas assessed. displays the risk of bias summary for individual studies, and displays the risk of bias graph. Details regarding the assessment of risk for each individual study are noted in Supplementary materials (Appendix 4).

Figure 2 (A) Risk of bias summary; (B) risk of bias graph.

Selection bias: Most studies used an automated randomization strategy that was considered low risk. Allocation concealment was not often described, but when studies were automated, we judged allocation concealment bias risk as low. There was a higher risk when personnel were involved in randomization and allocation. For example, Emmons et alCitation44 used personnel to randomize the participants and allocation concealment was not described. The study by Haug et alCitation45 was conducted in inpatient rehabilitation centers, and participants were randomized by the week of their admission. We judged there to be a risk of selection bias since personnel would know ahead of time which participants would be in each group. Similarly, the study by Shuter et alCitation46 was judged to be at high risk since clinic personnel were involved in allocation and were not blinded.

Performance and detection bias: We evaluated the included studies with regard to personnel and their ability to influence outcomes and found most studies to be at low risk for performance bias. Most studies were conducted on the Internet with no personnel involvement in the delivery of the intervention. When personnel did have opportunities to influence participants (eg, in a clinic setting), risk was judged as unclear when interactions with personnel were not described. There were two trials in which performance bias was judged as high risk. In the study by Swan et al,Citation47 quitline counselors were not blind to condition but interacted with all participants. The study by Mehring et alCitation48 was also judged to be at high risk for performance bias as unblinded personnel interacted with all participants. Most trials conducted outcome assessments via the Internet with no risk of detection bias. Some trials, however, had assessors to collect the outcome data by phone for at least some participants. A few studies did not describe their assessors as blinded, leading to ratings of unclear bias. No studies were believed to be at high risk of detection bias.

Attrition bias: Attrition is a particular challenge in web-based studies.Citation49 We focused on two elements when rating attrition bias: reporting outcomes and differential attrition by study arm. Reporting results with all randomized participants included and missing participants identified as smoking can protect against an overly optimistic interpretation of study findings that can occur when only responders are considered. With the exception of the studies by Bricker et alCitation50 and Humfleet et al,Citation51 all studies provided this type of ITT analysis. Only half of included studies reported significance testing of attrition rates. Studies that did not report attrition by study arm or that did not report whether significance testing of attrition rates across arms was conducted were rated as unclear with regard to attrition biasCitation37,Citation38,Citation51–Citation60 unless they had very high follow-up rates (eg, 96% and 99% follow-up in the study by Shuter et al).Citation46 Studies that reported significantly different attrition rates across arms were judged as high risk.Citation48,Citation61–Citation65 Studies with low follow-up rates but equivalent attrition across study arms were not rated as high risk, as has been done in previous reviews.Citation27 Attrition varied greatly from study to study, with follow-up rates ranging from >95% in the study by Shuter et alCitation46 to follow-up rates approximately 5% in Mañanes and Vallejo.Citation64

Study characteristics

Supplementary materials (Appendix 4) details the characteristics of included studies with regard to participants, interventions, comparison, outcomes, study design, risk of bias notations, and other characteristics relevant to this review.

Recruitment strategies

Most studies recruited participants via the Internet using a variety of strategies, including search engine advertising,Citation37,Citation53,Citation55,Citation66–Citation68 online ads,Citation39,Citation50,Citation55,Citation59,Citation62,Citation69–Citation71 and social media.Citation39,Citation50 Five trials recruited new registered users on the website being evaluated.Citation38,Citation56,Citation63,Citation64,Citation72 Other reactive recruitment sources included newspapers and magazines,Citation39,Citation47,Citation52,Citation62 print advertisements such as flyers, posters, and billboards,Citation52,Citation62,Citation73 radio and television advertisements,Citation39,Citation50,Citation52 and other paid advertising campaigns (unspecified).Citation22,Citation74 Several trials recruited through listservs, health plans, or survey panels.Citation40,Citation41,Citation47,Citation54,Citation61,Citation65,Citation73,Citation75–Citation77 Other proactive recruitment sources included health facilities or clinics,Citation44–Citation48,Citation51,Citation58,Citation60,Citation74 quitlines,Citation47,Citation75 and worksites.Citation57 Several studies used a combination of recruitment strategies.

Participants

Average age in most studies was mid-30s to late 40s; four studies explicitly focused on young adults and recruited participants who were 18–30 years of age.Citation40,Citation61,Citation76,Citation78 The majority of studies enrolled a higher proportion of women; several trials recruited an equal number of men and women.Citation64,Citation69,Citation70 Trials with a higher proportion of menCitation46,Citation51,Citation53,Citation55,Citation57,Citation58,Citation68,Citation76 recruited from sources where men were more likely to be represented (eg, workplace for operating engineers and human immunodeficiency virus [HIV] clinic). The only trial to enroll only women focused on cessation among pregnant smokers.Citation59 Approximately one-third of studies did not provide details about race; among those that did, the majority had primarily White participants. Some studies targeted specific racial or ethnic groups.Citation55,Citation64 Participants were most likely to have at least some college education; a majority of participants in three studies had a high school degree or less.Citation39,Citation51,Citation57

Intervention elements

The flexibility of the Internet allows for web-based cessation treatments to take myriad forms. In fact, this is one of the clearest findings from this review: there is currently no single or core web-based cessation treatment. The following groupings highlight common features among this diverse landscape.

Static web interventions: Ten trialsCitation22,Citation37,Citation44,Citation45,Citation50,Citation53,Citation62,Citation68–Citation70 included stand-alone static web components as part of the intervention condition. Static content was generally informational and non-tailored and contained content comparable to a printed cessation guide. Included in this category are static interventions in which the intervention is fully available and those that deliver intervention components over time. In some studies, static content was paired with additional features such as tailored feedback reports, text messaging, and/or social support.

Tailored feedback: Tailored feedback consists of advice or information provided to users based on responses to one or more assessments. Eight studiesCitation22,Citation37,Citation44,Citation45,Citation56,Citation62,Citation63,Citation75 examined interventions consisting largely of a feedback report. Tailoring was often performed on the basis of participants’ responses to an initial assessment and/or on the basis of participants’ stage of quitting. The form of tailored messages, however, varied greatly. In the study by Wangberg et al,Citation22 participants could receive up to 150 tailored emails over 6–12 months with tailoring on multiple factors. In contrast, EtterCitation63 provided participants with a single tailored letter, six to nine pages in length, based on a 62-item questionnaire.

Interactive/tailored web intervention: The majority of studies evaluated the effectiveness of interactive web interventions. Interactivity was defined as any part of a web intervention that solicited/required user input and included features such as exercises, quizzes, cost calculators, tailored messages, quit planning tools, training in coping strategies, and self-monitoring. A minority of the interactive interventions offered tailored content and/or guided users through the intervention based on information provided by the participant (eg, as in the study by Wangberg et al).Citation22

Coaching analogs and social support: A number of trials included social support resources such as peers, coaches, or counselors. The most common form of social support was the provision of an asynchronous discussion forum. Eight trialsCitation22,Citation37,Citation44,Citation45,Citation53,Citation67,Citation68,Citation77 included a discussion forum, either moderated by a peer or an expert, in at least some of the study arms. Seven trials included access to live coaching or counseling either via telephone, face-to-face counseling, or SMS text or email.Citation38,Citation48,Citation52,Citation57,Citation66,Citation77,Citation78 Two studies evaluated other methods of accessing social support.Citation40,Citation56

Other adjunctive components: Four trials described the use of SMS text messaging as part of the intervention.Citation48,Citation62,Citation69,Citation70 The two trials by Brendryen et al and Brendryen and KraftCitation69,Citation70 also included interactive voice response calls. The studies by Muñoz et alCitation37,Citation68 and Leykin et alCitation53 included an online eight-module cognitive-behavioral mood management component in some arms. The study by Simmons et alCitation76 included videos and the ability to create video content.

Medication: Several studies provided pharmacotherapy along with the web-based intervention. Nicotine replacement therapy (NRT) was the most common form of pharmacotherapy and was included in seven trials.Citation38,Citation41,Citation44,Citation46,Citation51,Citation57,Citation70 Medication treatment ranged from a 2-week starter kit used in the study by Fraser et alCitation38 to a 10-week starter kit used in the study by Strecher et al.Citation41 Two trialsCitation47,Citation58 included 12 weeks of varenicline. The study by Japuntich et alCitation52 included a 9-week course of bupropion.

Comparison arms

Six studies involved a no-treatment control condition. The studies by Elfeddali et alCitation62 and Haug et alCitation45 involved assessment-only control conditions. Smit et alCitation39 compared a fully automated, tailored Internet intervention to a no-treatment control. In a cluster randomized trial by Pisinger et al,Citation60 participants randomized to the control arm received usual care by their general practitioner. Swartz et alCitation73 tested a tailored, video-based Internet site in worksites against a waitlist control. Participants randomized to the control arm had access to the intervention after 90 days. Oenema et alCitation65 studied a multiple behavior change Internet intervention that addressed saturated fat intake, physical activity, and smoking. Smokers were encouraged to complete the smoking module first, which was interactive and included tailored feedback. Participants randomized to the control arm had access to the intervention after completing the posttreatment assessment at 1 month.

Five studies involved self-help print materials.Citation44,Citation51,Citation55,Citation69,Citation70 Three studies compared largely static Internet interventions to self-help print materials, and two compared interactive Internet interventions to print materials. Emmons et alCitation44 adapted Partnership for Health-2, a smoking cessation intervention for cancer survivors, for delivery via the Internet and compared it to a print version of the program. The print arm received a series of manuals designed to be interactive (eg, worksheets and personalized content). McDonnell et alCitation55 compared a static website composed of six sequential sections with a printed version of the same program. Humfleet et alCitation51 compared a static Internet intervention to a printed self-help guide among patients in an HIV clinic. Two studies by Brendryen et al and Brendryen and KraftCitation69,Citation70 evaluated the effect of an interactive, multimodal (Internet, email, SMS, interactive voice response) cessation intervention against self-help print materials. All participants in the study by Brendryen and KraftCitation70 received NRT.

Seven studies compared Internet interventions to face-to-face advice or counseling, either in individual or group format. The study by Dezee et alCitation58 involved in-person counseling (four 1.5-hour classes) and standard-dose varenicline. The control condition in the study by Japuntich et alCitation52 consisted of 9 weeks of twice-daily bupropion sustained release, three brief individual counseling sessions, and five follow-up visits. In a cluster randomized trial conducted by Mehring et alCitation48 within primary care clinics, participants randomized to the control arm received usual care and advice from their practitioner. A pilot study by Shuter et alCitation46 among HIV clinic patients randomized participants in the control arm to standard care, defined as brief advice to quit and self-help brochure. All subjects were offered nicotine patches. An experimental study by Simmons et alCitation76 included a group-based intervention as one of the controls. In small groups, students reviewed paper versions of the content from the Internet intervention and discussed it during a group discussion. In the study by Humfleet et al,Citation51 the control arm received six sessions of 40–60-minute in-person counseling plus NRT. In a cluster randomized trial by Pisinger et al,Citation60 general practitioners provided brief cessation counseling and referred smokers to five sessions of group-based counseling.

Two studies involved telephone counseling as a comparison condition.Citation47,Citation57 In the study by Choi et al,Citation57 participants were encouraged to call a toll-free telephone quitline and use NRT. A three-arm trial by Swan et alCitation47 compared proactive telephone counseling, an interactive website based on the same program, and a combined phone + Internet intervention. All participants received varenicline.

Twenty-three trials compared an interactive and/or tailored Internet intervention with a less intensive, static or generic Internet intervention.Citation22,Citation37,Citation38,Citation40,Citation41,Citation49,Citation53,Citation54,Citation56,Citation59,Citation61,Citation63,Citation64,Citation66–Citation68,Citation71,Citation72,Citation74–Citation78 Two of these studies examined the active ingredients of an Internet intervention using a factorial design.Citation41,Citation54 The remainder of the trials employed two- or three-arm randomized designs to examine the comparative effectiveness of different Internet interventions.

Outcome measures

The primary endpoints differed widely among the studies, ranging from 1 or 2 months post randomizationCitation56,Citation59,Citation65 to 15 months post randomization.Citation44 Most studies used self-reported abstinence measures (ie, 7-day, 30-day abstinence) as the primary outcome abstinence metric. A small number of studies used more conservative metrics of self-reported abstinence.Citation56,Citation62,Citation72,Citation74 Humfleet et al,Citation51 Japuntich et al,Citation52 Shuter et al,Citation46 Simmons et al,Citation76 and Dezee et alCitation58 collected carbon monoxide samples; Mehring et alCitation48 collected urine cotinine; and Pisinger et alCitation60 confirmed smoking status via urine cotinine through mailed urine samples. In each of these trials, clinic-based or local recruitment/intervention made biochemical verification feasible.

Effects of interventions

Internet interventions compared to an assessment-only or waitlist control

Prior to analysis, we pooled the intervention arms used in the study by Elfeddali et alCitation62 using data from Sample 1 as reported in the manuscript. We excluded the study by Oenema et alCitation65 from this analysis since the primary outcome was measured at 1 month post randomization and was based on self-reported abstinence in response to “Do you smoke?” We excluded the study by Pisinger et alCitation60 because of the low usage of Internet intervention. Pooled results from the four studies included Internet interventions () demonstrated a statistically significant effect in favor of the intervention (RR 1.60, 95% CI 1.15–2.21). However, results should be interpreted with caution as statistical heterogeneity was high (I2=51.7%). In addition, the study by Elfeddali et alCitation62 was at high risk of attrition bias since follow-up attrition was higher in both intervention arms, though this likely resulted in an underestimate of the potential intervention effect under ITT analysis.

Static Internet interventions compared to self-help print materials

The study by Humfleet et alCitation51 was excluded since we could not calculate ITT abstinence rates based on data presented in the manuscript. Pooled results from the studies by Emmons et alCitation44 and McDonnell et alCitation55 () found a nonsignificant effect in favor of the print materials (RR 0.83, 95% CI 0.63–1.10). Both studies included in this analysisCitation44,Citation55 were at low risk of bias and had no statistical heterogeneity (I Citation2=0%).

Interactive Internet interventions compared to self-help print materials

Pooled results from the two studies by Brendryen et al and Brendryen and KraftCitation69,Citation70 () found a statistically significant effect in favor of the interactive Internet intervention (RR 2.10, 95% CI 1.25–3.52). Statistical heterogeneity was low (I2=41.6%), and both studies were at low risk of bias.

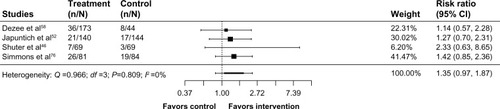

Internet interventions compared to face-to-face counseling

The study by Humfleet et alCitation51 was excluded from this analysis since we could not calculate ITT abstinence rates based on data presented in the manuscript. The study by Pisinger et alCitation60 was excluded because of the low usage of the Internet intervention; only 15.8% of participants randomized to this arm accessed the program. The study by Mehring et alCitation48 was excluded because of the high risk of attrition bias: response rates were 85% and 59% for control and intervention, respectively. Pooled results from four studiesCitation46,Citation52,Citation58,Citation76 () found a nonsignificant effect in favor of Internet interventions (RR 1.35, 95% CI 0.97–1.87, I2=0%).

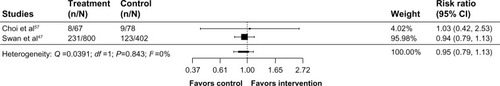

Internet interventions compared to telephone counseling

Prior to the analysis, we combined the two arms from the study by Swan et alCitation47 that involved Internet treatment (Web, Phone + Web) and compared it to telephone counseling. Pooled results from the studies by Choi et alCitation57 and Swan et alCitation47 () found a nonsignificant effect in favor of telephone counseling (RR 0.95, 95% CI 0.79–1.13, I2=0%).

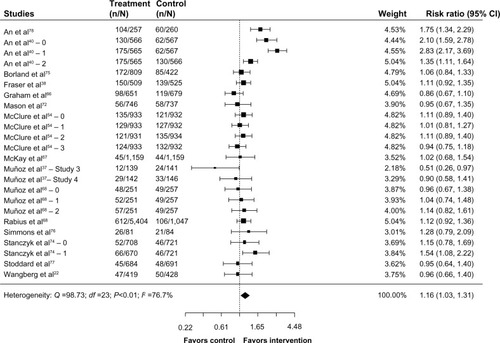

Internet interventions compared to other websites

Twenty-three trials compared Internet interventions to other web-based interventions. Excluded from this analysis were the studies by Bricker et alCitation50 and Berg et alCitation61 (pilot studies focused on feasibility, no power analysis was conducted); Etter,Citation63 Herbec et al,Citation59 and Strecher et alCitation56 (primary outcome assessed at <3 months); Leykin et alCitation53 (low rates of follow-up and high risk for attrition bias); Mañanes and VallejoCitation64 (very low follow-up rates <5%); and Strecher et alCitation41 (fractional factorial design precludes reporting of main effects). Pooled results for the remaining 15 trials (24 comparisons) found a significant effect in favor of Internet interventions compared to other websites (RR 1.16, 95% CI 1.03–1.31, I2=76.7%). The forest plot is presented in . Two trials with college students in the study by An et alCitation40,Citation78 showed significant effects for the two experimental conditions over the control condition, and for a personally tailored website with peer coaching over the personally tailored website alone. In the study by Stanczyk et al,Citation74 there was a significant effect of the computer-tailored video-based website over a static website with general information. Of the remaining 19 comparisons, eleven showed nonsignificant effects in favor of the experimental condition, with RRs at or below 1.34. In the study by McClure et al,Citation54 three of the four comparisons favored the more intensive/experimental factor over the control. Nonsignificant effects in favor of the control arm were observed in the studies by Graham et al,Citation66 Mason et al,Citation72 McClure et alCitation54 (email factor), Muñoz et alCitation68 (static website + email vs static website), Muñoz et alCitation37 (study 3 and study 4), Stoddard et al,Citation77 and Wangberg et al.Citation22

Figure 8 Internet interventions compared to other websites.

Abbreviation: CI, confidence interval.

Discussion

The goal of this systematic review was to evaluate the literature regarding the effectiveness of Internet cessation interventions, with particular reference to other cessation interventions supported by treatment guidelines. We reviewed 40 randomized trials that included 98,530 participants published from January 1990 through April 2015. These studies varied considerably with regard to the intervention features, comparison conditions, participant characteristics, and cessation outcome. However, grouping studies by the nature of the comparison condition and by intervention type yielded the following findings: 1) Internet interventions outperformed assessment-only/waitlist controls, 2) largely static Internet interventions were equivalent to self-help print materials, 3) interactive Internet interventions outperformed self-help print materials, 4) Internet interventions appeared equivalent to counseling delivered via face-to-face and telephone interventions, and 5) Internet interventions outperformed a range of website controls, although statistical and clinical heterogeneity were high.

The finding that interactive Internet interventions outperformed print materials but largely static interventions did not is consistent with previous reviews,Citation27 with a larger number of studies included herein. Delivery of static content via the Internet may increase its reach, but engagement with static content online would be expected to be comparable to print content, which has not been shown to significantly increase abstinence rates.Citation8 Self-assessments, self-monitoring, quitting-specific exercises, games, and social communications are now commonplace elements of online interactivity and are expected by end users. We note that the interventions included in these analyses were all published in the past 5 years, well past the advent of Web 2.0 social technologies and the proliferation of interactive components enabled by using JavaScript, Adobe Flash, and other languages that allow for a robust web experience. Results highlight the fact that the true potential of the Internet in promoting cessation is not exemplified by largely static interventions.

Our analyses did not detect significant differences between Internet interventions and face-to-face or telephone counseling. These findings are comparable to the results reported in the study by Civljak et al,Citation27 but with a larger number of trials. The studies of face-to-face counseling involved a range of counseling formats, including brief advice in the study by Shuter et al,Citation46 individual counseling in the study by Japuntich et al,Citation52 and group interventions in the studies by Dezee et alCitation58 and Simmons et al.Citation76 Effect sizes favored Internet interventions in each of these comparisons, but did not reach statistical significance. In comparisons of Internet interventions with telephone counseling, Choi et alCitation57 found a nonsignificant effect in favor of the Internet intervention, whereas Swan et alCitation47 found a nonsignificant effect in favor of telephone counseling. The equivalence of Internet interventions to these approaches lends support to the notion that Internet interventions may belong alongside face-to-face and telephone counseling interventions in tobacco treatment guidelines.

The largest group of studies compared two or more Internet interventions. More than two-thirds of comparisons in this category favored the experimental condition, perhaps signaling significant progress in the development of modern, engaging, rigorous, and effective Internet cessation interventions. Identifying the active ingredients of Internet interventions is an important area for future research, yet only three studies used factorial designs to compare specific features in order to optimize the effectiveness of Internet interventions.Citation38,Citation41,Citation54 Given the efficiency of this type of design and the speed with which it can advance the science of Internet interventions, more research of this type is needed.

Our results may not be as conservative as those reported in the study by Civljak et al.Citation27 Our use of the primary outcome specified in each trial rather than the longest available follow-up is methodologically sound given that many analyses of longer-term follow-up may have been underpowered; however, it could result in more optimistic, shorter-term outcomes than those presented elsewhere. In addition, our coverage of adherence and engagement is limited based on the nature and scope of this review. A large and growing number of studies point to engagement as a critical element in promoting abstinence.Citation79 We gathered information on engagement strategies for descriptive purposes but did not examine this as a moderating variable. Future reviews are encouraged to consider this important aspect of effectiveness.

Conclusion

In summary, based on this review of >10 years of research on Internet cessation interventions, the field has advanced significantly with newer interventions incorporating more interactive and engaging features. Six previous reviews have reported a mixture of conclusions, some more encouraging than others. Our goal was to address a practical question of relevance to payers and other decision makers regarding the role of Internet interventions in comprehensive tobacco control. As noted by the US Preventive Services Task Force,Citation26 “The best and most effective combinations [of cessation interventions] are those that are acceptable to and feasible for an individual patient.” Given the significant uptake of Internet interventions, their superiority to other broad reach cessation interventions (ie, print materials), and equivalence to other currently recommended treatment modes (telephone and in-person counseling), the results of this review suggest that Internet interventions have an important role to play in the arsenal of tobacco-dependence treatments.

Acknowledgments

The authors appreciate the contributions of Erik Augustson, PhD, MPH, who provided feedback on the study protocol. Support for the use of the EndNote X7.3 and EPPI-Reviewer 4.0 software was provided by Truth Initiative (formerly the American Legacy Foundation).

Disclosure

Amanda L Graham, Sarah Cha, and Megan A Jacobs are employees of Truth Initiative, a nonprofit public health foundation that runs BecomeAnEX.org, a web-based smoking cessation program. Kelly M Carpenter, Sam Cole, and Margaret Raskob are employees of Alere Wellbeing, a for-profit company that offers the Quit For Life comprehensive smoking cessation program which includes Web Coach®, a web-based smoking cessation intervention. Heather Cole-Lewis is an employee of Johnson & Johnson Health and Wellness Solutions, a for-profit company that offers Breathe®, a digital health coaching programs for smoking cessation. During the conduct of this study, Heather Cole-Lewis was an employee of ICF International which is a contractor to the National Cancer Institute (NCI) of the National Institutes of Health and supports Smokefree.gov, the NCI smoking cessation website. The authors report no other conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- Deloitte [webpage on the Internet]2014 Global Health Care Outlook: Shared Challenges, Shared Opportunities2014 Available from: http://www2.deloitte.com/content/dam/Deloitte/global/Documents/Life-Sciences-Health-Care/dttl-lshc-2014-global-health-care-sector-report.pdfAccessed February 20, 2016 Archived by WebCite® at http://www.webcitation.org/6glLGbAV3

- Office of the National Coordinator for Health Information TechnologyConnecting Health and Care for the Nation A Shared Nationwide Interoperability Roadmap, Draft Version 1.0Office of the National Coordinator for Health Information TechnologyWashington, DC2015 Available from: https://www.healthit.gov/sites/default/files/hie-interoperability/nationwide-interoperability-roadmap-final-version-1.0.pdfAccessed November 14, 2015 Archived by WebCite® at http://www.webcitation.org/6glLdmZCh

- GriffithsFLindenmeyerAPowellJLowePThorogoodMWhy are health care interventions delivered over the Internet? A systematic review of the published literatureJ Med Internet Res200682e1016867965

- EtterJFThe Internet and the industrial revolution in smoking cessation counsellingDrug Alcohol Rev2006251798416492580

- MurrayEInternet-delivered treatments for long-term conditions: strategies, efficiency and cost-effectivenessExpert Rev Pharmacoecon Outcomes Res20088326127220528378

- World Health OrganizationWHO Report on the Global Tobacco Epidemic, 2008: The MPOWER PackageGenevaWorld Health Organization2008 Available from: http://www.who.int/tobacco/mpower/2008/en/Accessed November 02, 2015 Archived by WebCite® at http://www.webcitation.org/6glLkPkaY

- World Health Organization [webpage on the Internet]Tobacco Fact Sheet2009 Available from: http://www.who.int/nmh/publications/fact_sheet_tobacco_en.pdfAccessed February 20, 2016 Archived by WebCite® at http://www.webcitation.org/6glLMdeI2

- FioreMJaénCBakerTTobacco Use and Dependence Guideline PanelTreating Tobacco Use and Dependence: 2008 Update Clinical Practice GuidelineRockville, MDU.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Public Health Service2008

- PatnodeCDHendersonJTThompsonJHSengerCAFortmannSPWhitlockEPBehavioral Counseling and Phamacotherapy Interventions for Tobacco Cessation in Adults, Including Pregnant Women: A Review for the U.S. Preventive Services Task ForceRockville, MDAgency for Healthcare Research and Quality2015

- National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE)Stop Smoking Services, NICE guidelines [PH10] Available from: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ph10Accessed: 2016-03-27 Archived by WebCite® at http://www.webcitation.org/6gK0VbclFLondonNational Institute for Health and Care Excellence2008

- JamalADubeSRMalarcherAMShawLEngstromMCCenters for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC)Tobacco use screening and counseling during physician office visits among adults – National Ambulatory Medical Care Survey and National Health Interview Survey, United States, 2005–2009MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep201261suppl3845

- North American Quitline ConsortiumResults from the 2013 NAQC Annual Survey of Quitlines Available from: http://c.ymcdn.com/sites/www.naquitline.org/resource/resmgr/Research/FINALNAQCFY13.pptx.pdfNorth American Quitline ConsortiumPhoenix, AZ2015Accessed March 27, 2016 Archived by WebCite® at http://www.webcitation.org/6gJzi3pzW

- EtterJFPernegerTVAttitudes toward nicotine replacement therapy in smokers and ex-smokers in the general publicClin Pharmacol Ther20016917518311240982

- ShiffmanSBrockwellSEPillitteriJLGitchellJGUse of smoking-cessation treatments in the United StatesAm J Prev Med200834210211118201639

- ShinDWSuhBChunSThe prevalence of and factors associated with the use of smoking cessation medication in Korea: trend between 2005–2011PLoS One2013810e7490424130674

- KotzDFidlerJWestRFactors associated with the use of aids to cessation in English smokersAddiction200910481403141019549267

- European Network of Quitlines [webpage on the Internet]Guidelines to Best Practice for Smoking Cessation Websites2012 Available from: http://docplayer.net/6348332-European-network-of-quitlines-guidelines-to-best-practice-for-smoking-cessation-websites.htmlAccessed March 27, 2016 Archived by WebCite® at http://www.webcitation.org/6gK1Olczc

- North American Quitline Consortium [webpage on the Internet]Web-Based Services in the U.S. and Canada2014 Available from: http://map.naquitline.org/reports/web/Accessed February 20, 2016 Archived by WebCite® at http://www.webcitation.org/6glMHeK5X

- Alere Wellbeing Inc [webpage on the Internet]American Cancer Society Quit For Life Program2014 Available from: http://www.alerewellbeing.com/company/Accessed February 20, 2016 Archived by WebCite® at http://www.webcitation.org/6glMKLCOk

- Healthways [webpage on the Internet]Healthways Tobacco Cessation: QuitNet Comprehensive Kicks Habit with Greater Support2011 Available from: http://docslide.us/documents/healthways-tobacco-cessation-quitnet-comprehensive-kicks-habits-with-greater-support.htmlAccessed February 20, 2016 Archived at http://www.webcitation.org/6gJzVZEna

- van MierloTVociSLeeSFournierRSelbyPSuperusers in social networks for smoking cessation: analysis of demographic characteristics and posting behavior from the Canadian Cancer Society’s smokers’ helpline online and StopSmokingCenter.netJ Med Internet Res2012143e6622732103

- WangbergSCNilsenOAntypasKGramITEffect of tailoring in an Internet-based intervention for smoking cessation: randomized controlled trialJ Med Internet Res2011134e12122169631

- FoxSHealth Topics Available at http://www.pewinternet.org/Reports/2013/Health-online.aspxWashington, DCPew Research Center2013Accessed December 18, 2013 Archived by Webcitation.org: http://www.webcitation.org/6LxbeFGGv

- CobbNKGrahamALCharacterizing Internet searchers of smoking cessation informationJ Med Internet Res200683e1717032633

- EysenbachGKohlerCHealth-related searches on the InternetJAMA200429124294615213205

- SiuALU.S. Preventive Services Task ForceBehavioral and pharmacotherapy interventions for tobacco smoking cessation in adults, including pregnant women: U.S. Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statementAnn Intern Med2015163862263426389730

- CivljakMSteadLFHartmann-BoyceJSheikhACarJInternet-based interventions for smoking cessationCochrane Database Syst Rev20137CD00707823839868

- HigginsJGreenS[webpage on the Internet]Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions Version 5.1.02011 Available from: http://handbook.cochrane.org/Accessed February 20, 2016 Archived by WebCite® at http://www.webcitation.org/6glMBOgSC

- LiberatiAAltmanDGTetzlaffJThe PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate health care interventions: explanation and elaborationJ Clin Epidemiol20096210e1e3419631507

- BockBCGrahamALWhiteleyJAStoddardJLA review of web-assisted tobacco interventions (WATIs)J Med Internet Res2008105e3919000979

- BarakAKleinBProudfootJGDefining Internet-supported therapeutic interventionsAnn Behav Med200938141719787305

- RitterbandLMThorndikeFPCoxDJKovatchevBPGonder-FrederickLAA behavior change model for Internet interventionsAnn Behav Med2009381182719802647

- RileyWTRiveraDEAtienzaAANilsenWAllisonSMMermelsteinRHealth behavior models in the age of mobile interventions: are our theories up to the task?Transl Behav Med201111537121796270

- ThomasJBruntonJGraziosiSEPPI-Reviewer 4.0: Software for Research SynthesisLondonSocial Science Research Unit, Institute of Education, University of London2010

- AlkhaldiGHamiltonFLLauRWebsterRMichieSMurrayEThe effectiveness of technology-based strategies to promote engagement with digital interventions: a systematic review protocolJMIR Res Protoc201542e4725921274

- EysenbachGGroupCECONSORT-EHEALTH: improving and standardizing evaluation reports of web-based and mobile health interventionsJ Med Internet Res2011134e12622209829

- MuñozRFLenertLLDelucchiKToward evidence-based Internet interventions: a Spanish/English web site for international smoking cessation trialsNicotine Tob Res200681778716497602

- FraserDKobinskyKSmithSSKramerJTheobaldWEBakerTBFive population-based interventions for smoking cessation: a MOST trialTransl Behav Med20144438239025584087

- SmitESVriesHHovingCEffectiveness of a web-based multiple tailored smoking cessation program: a randomized controlled trial among Dutch adult smokersJ Med Internet Res2012143e8222687887

- AnLCDemersMRKirchMAA randomized trial of an avatar-hosted multiple behavior change intervention for young adult smokersJ Natl Cancer Inst Monogr201320134720921524395994

- StrecherVJMcClureJBAlexanderGLWeb-based smoking-cessation programs: results of a randomized trialAm J Prev Med200834537338118407003

- MathieuEMcGeechanKBarrattAHerbertRInternet-based randomized controlled trials: a systematic reviewJ Am Med Inform Assoc201320356857623065196

- HigginsJPThompsonSGDeeksJJAltmanDGMeasuring inconsistency in meta-analysesBMJ2003327741455756012958120

- EmmonsKMPuleoESprunck-HarrildKPartnership for health-2, a web-based versus print smoking cessation intervention for childhood and young adult cancer survivors: randomized comparative effectiveness studyJ Med Internet Res20131511e21824195867

- HaugSMeyerCJohnUEfficacy of an Internet program for smoking cessation during and after inpatient rehabilitation treatment: a quasi-randomized controlled trialAddict Behav201136121369137221907496

- ShuterJMoralesDAConsidine-DunnSEAnLCStantonCAFeasibility and preliminary efficacy of a web-based smoking cessation intervention for HIV-infected smokers: a randomized controlled trialJ Acquir Immune Defic Syndr2014671596625118794

- SwanGEMcClureJBJackLMBehavioral counseling and varenicline treatment for smoking cessationAm J Prev Med201038548249020409497

- MehringMHaagMLindeKWagenpfeilSSchneiderAEffects of a guided web-based smoking cessation program with telephone counseling: a cluster randomized controlled trialJ Med Internet Res2014169e21825253539

- MurrayEKhadjesariZWhiteIRMethodological challenges in online trialsJ Med Internet Res2009112e919403465

- BrickerJWyszynskiCComstockBHeffnerJLPilot randomized controlled trial of web-based acceptance and commitment therapy for smoking cessationNicotine Tob Res201315101756176423703730

- HumfleetGLHallSMDelucchiKLDilleyJWA randomized clinical trial of smoking cessation treatments provided in HIV clinical care settingsNicotine Tob Res20131581436144523430708

- JapuntichSJZehnerMESmithSSSmoking cessation via the Internet: a randomized clinical trial of an Internet intervention as adjuvant treatment in a smoking cessation interventionNicotine Tob Res20068suppl 1S59S6717491172

- LeykinYAguileraATorresLDPerez-StableEJMuñozRFInterpreting the outcomes of automated Internet-based randomized trials: example of an International Smoking Cessation StudyJ Med Internet Res2012141e522314016

- McClureJBPetersonDDerryHExploring the “active ingredients” of an online smoking intervention: a randomized factorial trialNicotine Tob Res20141681129113924727369

- McDonnellDDKazinetsGLeeHJMoskowitzJMAn Internet-based smoking cessation program for Korean Americans: results from a randomized controlled trialNicotine Tob Res201113533634321330285

- StrecherVJShiffmanSWestRRandomized controlled trial of a web-based computer-tailored smoking cessation program as a supplement to nicotine patch therapyAddiction2005100568268815847626

- ChoiSHWaltjeAHRonisDLWeb-enhanced tobacco tactics with telephone support versus 1-800-QUIT-NOW telephone line intervention for operating engineers: randomized controlled trialJ Med Internet Res20141611e25525447467

- DezeeKJWinkJSCowanCMInternet versus in-person counseling for patients taking varenicline for smoking cessationMil Med2013178440140523707824

- HerbecABrownJTomborIMichieSWestRPilot randomized controlled trial of an Internet-based smoking cessation intervention for pregnant smokers (‘MumsQuit’)Drug Alcohol Depend201414013013624811202

- PisingerCJorgensenMMMollerNEDossingMJorgensenTA cluster randomized trial in general practice with referral to a group-based or an Internet-based smoking cessation programmeJ Public Health (Oxf)2010321627019617300

- BergCJStrattonESokolMSantamariaABryantLRodriguezRNovel incentives and messaging in an online college smoking interventionAm J Health Behav201438566868024933136

- ElfeddaliIBolmanCCandelMWiersRWde VriesHPreventing smoking relapse via web-based computer-tailored feedback: a randomized controlled trialJ Med Internet Res201214487102

- EtterJFComparing the efficacy of two Internet-based, computer-tailored smoking cessation programs: a randomized trialJ Med Internet Res200571e215829474

- MañanesGVallejoMAUsage and effectiveness of a fully automated, open-access, Spanish web-based smoking cessation program: randomized controlled trialJ Med Internet Res2014164e11124760951

- OenemaABrugJDijkstraAde WeerdtIde VriesHEfficacy and use of an Internet-delivered computer-tailored lifestyle intervention, targeting saturated fat intake, physical activity and smoking cessation: a randomized controlled trialAnn Behav Med200835212513518363076

- GrahamALCobbNKPapandonatosGDA randomized trial of Internet and telephone treatment for smoking cessationArch Intern Med20111711465321220660

- McKayHGDanaherBGSeeleyJRLichtensteinEGauJMComparing two web-based smoking cessation programs: randomized controlled trialJ Med Internet Res2008105e4019017582

- MuñozRFBarreraAZDelucchiKPenillaCTorresLDPerez-StableEJInternational Spanish/English Internet smoking cessation trial yields 20% abstinence rates at 1 yearNicotine Tob Res20091191025103419640833

- BrendryenHDrozdFKraftPA digital smoking cessation program delivered through Internet and cell phone without nicotine replacement (happy ending): randomized controlled trialJ Med Internet Res2008105e5119087949

- BrendryenHKraftPHappy ending: a randomized controlled trial of a digital multi-media smoking cessation interventionAddiction2008103347848418269367

- RabiusVPikeKJWiatrekDMcAlisterALComparing Internet assistance for smoking cessation: 13-month follow-up of a six-arm randomized controlled trialJ Med Internet Res2008105e4519033146

- MasonDGilbertHSuttonSEffectiveness of web-based tailored smoking cessation advice reports (iQuit): a randomized trialAddiction2012107122183219022690882

- SwartzLHNoellJWSchroederSWAryDVA randomised control study of a fully automated Internet based smoking cessation programmeTob Control200615171216436397

- StanczykNESmitESSchulzDNAn economic evaluation of a video- and text-based computer-tailored intervention for smoking cessation: a cost-effectiveness and cost-utility analysis of a randomized controlled trialPLoS One2014910e11011725310007

- BorlandRBalmfordJBendaPPopulation-level effects of automated smoking cessation help programs: a randomized controlled trialAddiction2013108361862822994457

- SimmonsVNHeckmanBWFinkACSmallBJBrandonTHEfficacy of an experiential, dissonance-based smoking intervention for college students delivered via the InternetJ Consult Clin Psychol201381581082023668667

- StoddardJLAugustsonEMMoserRPEffect of adding a virtual community (bulletin board) to smokefree.gov: randomized controlled trialJ Med Internet Res2008105e5319097974

- AnLCKlattCPerryCLThe RealU online cessation intervention for college smokers: a randomized controlled trialPrev Med200847219419918565577

- DonkinLChristensenHNaismithSLNealBHickieIBGlozierNA systematic review of the impact of adherence on the effectiveness of e-therapiesJ Med Internet Res2011133e5221821503