Abstract

Background

Policymakers and treatment providers must consider the role of gender when designing effective treatment programs for female substance abusers. This study had two aims. First, to examine female substance abusers’ perceptions regarding factors that contribute to their retention (and therefore positive treatment outcomes) in a women-only therapeutic community in Northern Israel. Second, to explore pretreatment internal and external factors including demographic, personal and environmental factors, factors associated with substance use and with the treatment process, and networks of support that contribute to retention and abstinence.

Methods

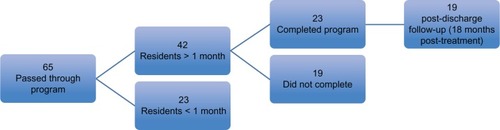

The study was a conducted using a mixed methods approach. Semi-structured qualitative interviews examining perceptions towards treatment were conducted in five focus groups (n = 5 per group; total n = 25). Intake assessments and a battery of questionnaires examining pretreatment internal and external factors related to treatment retention and abstinence were collected from 42 women who were treated in the program during the 2 year study period. Twenty-three women who completed the 12 month program were compared to the 19 women who did not, using chi-square for categorical variables and t-tests for continuous variables. Nineteen of the 23 women who completed the questionnaires also completed a post-treatment follow-up questionnaire.

Results

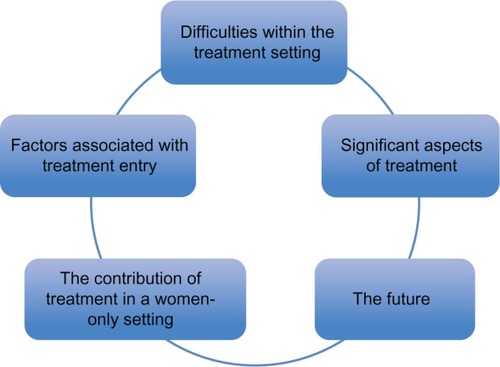

A content analysis of the interviews revealed five central themes: factors associated with treatment entry; impact of treatment in a women-only setting; significant aspects of treatment; difficulties with the setting; prospects for the future. Analysis of the questionnaires revealed that compared to non-completers, completers had fewer psychiatric symptoms, higher levels of introverted behavior in stressful situations, a better sense of coherence, and less ability to share emotions. No significant differences were found with regard to demographic and substance use factors. All 19 women who completed treatment and the follow-up questionnaire remained abstinent from illicit drugs for 18 months following the end of treatment.

Conclusion

Results indicate that women see the women-only treatment setting as extremely significant. Also, there is a profile of psychiatric co-morbidity, extrapunitiveness, and fewer personal resources that predict a risk for attrition. Thus, women at risk for attrition may be identified early and treatment staff can utilize the results to assist clients in achieving their treatment goals. Results can inform policymakers in making decisions regarding the allocation of resources, by pointing to the importance of long-term women-only residential treatment in increasing positive treatment outcomes.

Background

Substance abuse is a major public health issue with significant societal and economic costs.Citation1–Citation3 Studies across various populations and treatment modalities have shown that the benefits of treatment outweigh the costs.Citation4–Citation7 Despite this evidence, additional evaluation research is needed in order for us to be able to provide better advocacy for our clients and battle the current political climate, which is still skeptical of allocating resources to substance abuse treatment.Citation8

This study evaluates a women-only treatment program for substance abusing women in Israel. The significance of this study is twofold. First, the issue of treatment for women in a women-only setting is a relatively new approach for serving this unique population. Second, there is limited research examining the effectiveness of these programs. In addition, positive outcomes for women in these types of programs may encourage decision makers to divert additional funding to these programs. Currently, programs serving women-only suffer from a substantial lack of funding.Citation9

Women substance abusers are different from men in many aspects including demographic factors (such as education and parenthood), substance use factors and personal characteristics (such as sexual abuse), physical and psychological characteristics.Citation10–Citation13 Because of these differences, women have different treatment needs, but they are often treated together with men.Citation9,Citation14,Citation15

The amount of women who seek treatment has increased significantly in the last few decades.Citation16,Citation17 Research, as well as practice experience, suggest there is a need for gender sensitive treatment and that women substance abusers do better in treatment when separated from men.Citation18,Citation19 Specifically, research has shown that women-tailored treatment increases retention and decreases dropout rates.Citation16,Citation20 Moreover, it has been suggested that long term residential settings are more sensitive to women’s unique needs than outpatient treatment, detoxification units or Methadone maintenance.Citation21,Citation22

Until 2001, existing therapeutic communities in Israel were all gender-mixed and were not tailored to women’s needs. Among women starting treatment in these therapeutic communities, the percentage of dropouts was very high (80%) and primarily during the first month of treatment. In 2001, the Israel Anti-Drug Authority decided to meet the challenge and opened the first women-only therapeutic community in Northern Israel.

The aim of this study was to evaluate this first women-only therapeutic community in Israel. This study can provide treatment personnel and decision makers with important information about women substance abusers, their characteristics, their reasons for entering treatment and effective components of treatment services. Results can inform policymakers in making decisions regarding the allocation of resources, by pointing to the importance of long-term women-only residential treatment in increasing positive treatment outcomes.

The study employed a mixed methods approach: a quantitative study aimed at exploring pretreatment internal and external factors contributing to treatment retention and abstinence and a qualitative study aimed at exploring women’s perceptions regarding factors that contribute to their entry and retention in treatment.

The setting

The women-only therapeutic community opened in 2001 and operates under the Ministry of Welfare and the Association for Public Health Services, The Haifa Drug Abuse Treatment Center, Rambam Medical Center and the Israeli Anti-Drug Authority. In 2001, and throughout the entire study period, there were 12 beds in the program. In 2009 the program was expanded to 18 beds.

The program is situated in the heart of a large city, making it possible to take advantage of available social, community, municipal and medical services. In this way the women are exposed to real-life situations and learn to deal with them effectively. For instance, women who need medical services will receive it in regular health clinics outside the therapeutic community. In later stages of treatment, some of the women secure jobs and begin employment in the city while still living in the home. Several others choose to continue their education or begin vocational training.

The length of stay in the program is 12 months. The main goal is that, upon completion of the program, each graduate will have the ability to lead a drug-free and independent life on functional, emotional, personal and interpersonal levels. Stated differently, the goal is to bring about growth and individual change, without the use of addictive substances.

Referrals to the program are made by detoxification units, prison and correction services, social agencies, and by self-referral. Women must be abstinent from illicit drug use for a period of several weeks to be admitted to the program, and many of them are treated at detoxification units prior to entering the therapeutic community.

An all-female professional and experienced staff is present on the premises around the clock. The staff is comprised of social workers and counselors. All the counselors are in recovery themselves, and several of the newer counselors are graduates of the therapeutic community. This to make clients feel more comfortable expressing themselves on intimate and gender sensitive issues, and so that they are exposed to other, more productive ways of functioning and coping.

The approach of the program is holistic and based on a bio-psycho-social model that utilizes a wide variety of therapeutic solutions and activities including, but not limited to,

– Individual and group therapy.

– Various groups on issues such as day-to-day operations, boundaries, hierarchy of the community, and time management.

– Extracurricular activities: art and culture, current events, drama club, drum circle.

– Medical and mental health follow-ups.

Study overview

As mentioned above, this study was comprised of two components. The first component was a quantitative study aimed at comparing women who completed the program with those who did not, in order to understand what factors contribute to treatment retention and completion. The second component was a qualitative study that explored women’s perceptions regarding the factors that lead them to seek treatment and help them stay in treatment and remain abstinent. For both components, all protections for participants were put in place with accordance with ethical standards accepted in the US. Consent forms detailing the research process, the voluntary nature of the research, confidentiality, risks, and benefits were provided to and signed by all the women.

First, the quantitative component of the study and its results will be presented. The methods of the qualitative component of the study will follow, along with a brief summary of its main results. Finally, the authors will draw conclusions and implications for future research and practice.

The quantitative component

Sample, method and measures

Sixty-five women passed through the program during the study period (2002–2005). All women completed an intake questionnaire designed to gather demographic data and substance use data, as it is part of the program’s regular operations. At intake, as part of the regular operations of the program, the women were also assessed by the program’s intake therapist about their motivation for entering treatment (external versus internal motivation), their ability to share emotions, and their level of personal functioning (both measured on a scale of 1 to 5). Also during intake they were asked to participate in the study, entailing a battery of questionnaires (detailed below) to be administered 1–2 months after entry in the program, as well as a follow-up 18 months post-treatment. The questionnaires were administered to 42 of the women, while 23 others dropped out before completing the first month. These additional questionnaires were concerned with factors associated with the treatment process, personal and environmental factors, for example, body images, mental health, self-esteem, sense of coherence, and with networks of support.

Of the 42 women who completed the questionnaires, 23 completed the 12 month program. The study compared these 23 women to the 19 who dropped out after one month, before completing the program. Nineteen of the 23 women who completed the program also completed a post-discharge follow-up questionnaire 18 months later. For a graphic representation of these total sample sizes, please refer to .

Figure 1 Number of women who entered the program, were retained in the program, completed the program and completed follow-up questionnaires.

The average age of all 42 women who completed the questionnaires was 30, ranging from 19 to 48. Sixty-two percent were born in Israel and a large majority of the rest was born in the Former Soviet Union. Eighty-eight percent of them were unmarried, 36% were mothers and over 80% had at least a high school education.

An overwhelming majority (94%) of the sample was dependent on opiates, and 60% of the women reported two or more previous treatment experiences. While only 19% were previously incarcerated, 62% reported having suicidal thoughts or a suicide attempt. Finally, more than 55% reported at intake as having experienced physical and/or sexual abuse. Throughout the course of treatment, more women disclosed previous abuse and this number rose to over 90%. For a summary of the demographic, personal history, and substance use data, please refer to and .

Table 1 Demographic, personal history and substance use data as collected at intake – categorical variables (n = 42)

Table 2 Demographic and substance use data as collected at intake – continuous variables (n = 42)

Other than an intake questionnaire, which is part of the regular operations of the program, the women completed a battery of seven questionnaires during their second month of treatment:

The Mastery Scale developed by Pearlin and Schooler, and later adapted by Hobfull and Walfish,Citation23,Citation24 is designed to measure ‘the extent to which people see themselves as being in control of the forces that importantly affect their lives’.Citation25 The scale consists of 7 items tapping sense of control, on a scale of 1 (very little control) to 5 (very high control), for a total composite score of 1–35. The higher the score, the higher the sense of control. The scale was translated to Hebrew, and found to be valid and reliable, α = 0.79.Citation26

The Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale was developed by Rosenberg and later adapted by Hobfull and Walfish.Citation25,Citation27 The scale consists of 10 items, scored from 1 (strongly agree) to 5 (strongly disagree) with various statements on self-esteem. The scale was translated and validated for use with Hebrew speaking populations.Citation28 It has been widely used and reported internal consistency as the scale in Hebrew speaking samples has ranged from α = 0.78Citation28 to α = 0.87.Citation29

The Body Investment Scale, developed by Mikulincer and Orbach to measure emotional investment in the body, is specifically concerned with self-destructive behaviors.Citation29 They identified four separate aspects of the bodily self, measured by their 24-item scale: (1) body image feelings and attitudes, (2) measure comfort in physical contact with others, (3) reflect concern for body care, and (4) investment in body protection. The items are scored on a scale of 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree) and each of the 4 content areas is scored separately. The authors translated their measure to Hebrew and examined its psychometric, showing high internal consistency for all four aspects of body image.Citation29

The Picture Frustration Study, developed by Rosenzweig,Citation30 includes a projective format in which a participant views a series of 24 cartoonlike drawings that depict two persons involved in a variety of situations that are likely to be interpreted as frustrating for one of the characters in the drawing. The participant responds to each of the cartoon drawings by inserting a written statement to indicate the response of the character experiencing frustration.Citation31 Inherent in its format, the Rosenzweig Picture Frustration Study elicits data regarding how individuals handle aggression. Aggression can be directed outward (extra-aggression or extra-punitiveness) or inward (intraaggression or intro-punitiveness), or it can be minimized to the point of denial (impunitiveness).Citation30,Citation31

Mental Health Index (MHI) is a 38-item measure of psychological distress (anxiety, depression, loss of behavioral emotional control) and well-being (general positive affect, emotional ties). Each item is scored on a scale of 1 to 6, and the scores for each subgroup, as well as for overall distress and wellbeing, can be computed.Citation32 The MHI was translated and validated for use with the Israeli population.Citation33 It has been widely used since and reported internal consistency in Hebrew speaking samples has been consistently high; α > 0.85.Citation33–Citation35

The Sense of Coherence Questionnaire is a 29-item self-report to measure a person’s sense of coherence, defined as a global orientation, that expresses the extent to which one has a pervasive, enduring though dynamic, feeling of confidence that (1) the stimuli deriving from one’s internal and external environments in the course of living are structured, predictable, and explicable (comprehensibility); (2) the resources are available for one to meet the demands posed by these stimuli (manageability); and (3) these demands are challenges, worthy of investment and engagement (meaningfulness).Citation36 The questionnaire was translated and reported internal consistency in Hebrew speaking samples of substance abusers has ranged from α = 0.71Citation37 to α = 0.83.Citation38

The Social Network and Social Support Questionnaire for Methadone Patients (SSMP; El- Bassel, Cooper, Chen, and Schilling, 1998)Citation39 was modeled after the General Social Survey network data.Citation40 To capture the social environments surrounding the respondents, interviewers used two name generators to elicit the names of the most important individuals with whom the respondent had regular, frequent contact during the preceding three months (5 family members, 5 non-kin, users and non-users). Questions are designed to capture the network members’ demographic backgrounds (eg, ethnicity, age, gender and level of education), the network structures (eg, size, density, etc.) and the relational content of ties (eg, types of relationships, contact frequency and joint activities and affiliations).

In addition, the women who completed the program were asked to complete a follow-up questionnaire developed for this study, inquiring about drug use, legal issues, health, family status, living arrangements, employment, and networks of support.

Data analysis was conducted in two phases. First, descriptive statistics were computed for all variables, including frequencies and percentages for categorical variables, and means, standard deviations and ranges for continuous variables. Second, we conducted statistical analysis to compare the women who completed treatment with the women who did not. Chi-square tests were used for the categorical variables, and t-tests for the continuous variables. Results are presented in the following section.

Results

The two groups of women (the 23 who completed the program and the 19 who dropped out after one month) were compared with regard to their demographic, personal history, and substance use characteristics. No significant differences were found between the two groups with regard to their age, country of origin, marital status, education, age of first use, years using, previous abuse, or number of previous treatment attempts.

As part of the regular intake procedures at the program, the women were assessed by the intake therapist about their motivation for entering treatment (external versus internal motivation), their ability to share emotions, and their level of personal functioning, both measured on a scale of 1 to 5. Findings are presented in .

Table 3 Results – a comparison between completers and non-completers: therapist assessment for motivation for entering treatment, ability to share emotions and level of personal functioning

There were no significant differences between completers and non-completers with regard to their source of motivation or level of personal functioning. However, the intake therapist assessed the women who ultimately completed treatment as less able to share emotions (M = 2.12, SD = 1.27) than those who did not complete treatment (M = 3.29, SD = 0.83, F(1,29) = 8.77, P < 0.01).

Findings from the questionnaires administered to the women are presented in . These include a comparison between completers and non-completers on various personal characteristics.

Table 4 Results – a comparison between completers and non-completers

According to the data presented in , compared to non-completers (n = 19), women who completed treatment (n = 23) had a better sense of coherence, a better level of mental health, more introverted levels of aggression, and a higher concern for their bodies. Finally, it is important to note that, based on analysis of the Social Network and Social Support Questionnaire, no significant difference was found between completers and non-completers with regard to any of the social support or network variables.

Out of the 23 who completed the treatment program, 19 (82.6%) completed a post treatment follow-up questionnaire 18 months post-graduation. All 19 women who completed treatment and the follow-up questionnaire have remained abstinent from illicit drugs since their initial assessment. Only one of the women reported a single incidence of alcohol, which occurred 8 months after she left treatment. This finding was corroborated with staff at the community-based treatment services where the women were referred to for follow-up treatment and services.

None of the women who completed treatment were arrested or involved in prostitution. All women who suffered a physical or mental illness while in treatment pursued regular care in the community for their condition. Eighteen of the women were employed, ten regularly and eight held at least temporary positions. Finally, all 19 women reported that they did not maintain contact with friends who were users, and all were in regular contact with the therapeutic community.

Qualitative component

Methods

The qualitative study was conducted using a Phenomenological approach, in an attempt to describe the lived experiences of the participants.Citation41 The study was interested in exploring how women in the therapeutic community experience the treatment process and the changes occurring in their lives. Data for the qualitative component was collected via semi-structured interviews conducted in five focus groups. Focus groups can be a useful tool in exploratory research, when little is known about a particular content area.Citation42,Citation43 Focus groups can also be a cost-effective method for collecting valuable data.Citation43 In this study, focus groups were conducted until saturation was achieved, the content that was arising from the interviews began to repeat itself, and new themes were no longer emerging.

Five focus groups were conducted (n = 5 per group; total N = 25) over a period of 18 months. Participants were women living in a therapeutic community for at least 3 months at the time the focus group was conducted. All of the women who participated in the focus groups also contributed data to the quantitative portion of the evaluation. Two social workers, members of the research team who were not members of the staff, conducted the focus groups. Participants were promised confidentiality (all names used in the quotes below are pseudonyms).

Data analysis was conducted using content analysis, allowing the researcher to identify and code themes and patterns arising from the data.Citation44,Citation45 In phase one of the content analysis, interviews were transcribed and coded by two members of the research team using open coding to discover initial units of meaning.Citation41 In phase 2, transcripts were re-read and, using axial coding categories with additional units of meanings, were identified and grouped. The main themes emerging from the content analysis are presented in the following section.

Results

Women were asked about factors that contribute to their retention and abstinence within the framework of the women-only therapeutic community. An analysis of the content revealed five central themes (see also ):

Factors associated with treatment entry:

Almost all of the women interviewed described hitting rock bottom before seeking treatment at the therapeutic community. Many of the women had several unsuccessful previous treatment attempts, were engaged in prostitution, had lost their will to live, had legal problems, lost custody of their children, were estranged from their families or had a close call with death:

– I had nothing, no family, no friends. I wanted God to take me already … I was disconnected from everyone – my family gave up on me … I came here because I was fed up from everyone and myself. (Adi, group 3)

– I cursed my children, my husband’s family; I embarrassed him at work … I fought with my oldest son, told him they ruined my life, that I don’t love them. He called the police and I was arrested. They took out a restraining order. And then I went there and threatened to burn down the house. At first they didn’t want to let me come here, they were going to send me to prison because I was violent. (Sharon, group 3)

The majority of women arrived at the home feeling it was their last chance to turn their lives around after losing much of their identity as women, mothers, friends and partners, to substance abuse.

The contribution of treatment in a women-only setting: The women discussed how important it was for them to have treatment tailored to their needs as women, without men around as several of them had unsuccessful experiences in mixed-gender treatment communities in previous treatment attempts. They pointed to how important the intimacy of the home was to them, how it made them feel comfortable:

– We are all women here … Let’s say you were a prostitute, someone will make fun of you? No, they understand … You can say whatever you want … We all come from the same place, the same pit. (Dana, group 1)

– I’m real here. People identify with me, and I with them. For the first time I feel like a woman. I was afraid to be a woman, afraid to be myself. I like that if it’s only women, you can talk and work through problems. Men are destructive. (Michal, group 3)

Furthermore, the women described their identities before entering this setting as dependent on men and saw the women-only setting as significant in helping them discover who they were on their own. The other women were instrumental in helping them share their difficulties and life stories on the path to recovery.

– I can be me here. There are no men, there’s no sex. No interests related to sex. (Rachel, group 4)

– I was always around men, relying on them. And I’m a woman, and I lived as a man on the outside – I stole, I broke in. I didn’t recognize myself. The women here remind me who I am. I look at them and see me. It’s like a mirror. (Hannah, group 2)

Significant aspects of treatment:

The women pointed to boundaries such as the setting of home, the staff and treatment content, as significant for them. Several women discussed the importance of boundaries to the treatment process. They described chaotic lives and their need for structure and order. One woman said:

– Give me a break? They don’t do that here … That’s what I need [because] every time someone did I found myself using again. Nothing to it. (Noa, group 5)

The home-like environment provided a sense of security, a feeling that one is seen beyond the physical meaning of the word. The following quote from one of the women summarized sentiments echoed by many:

– I think what helps is that there is a feeling of home here … You feel free, you can talk about anything you want, they contain you, there’s a team, a group, and the power of a group … If you fall, there is someone to pick you up, you are not alone. It’s a small place, and intimate place, they see you, so they know how you feel … (Liat, group 4)

The staff, several of whom are former addicts, also contribute to the overall sense of security described by the women:

– First of all, they are addicts, like us. So they understand us better than anyone who wasn’t an addict. They know what we are going through, how we feel, because they experienced it in the flesh, so they know exactly how to take care of us. (Irena, Group 1)

Finally, women pointed to various treatment content as significant to their recovery process, specifically, how they are taught to feel, function as mothers and be drug free:

– Some of us never felt, we didn’t know what it meant to hurt, to be happy, reserved. We didn’t know anything. Here they teach us that if we feel something not to go use, talk about it … I used to cope using the drug, which is not a solution. Today I can cope … today if I’m having difficulties, I have individual therapy, I have a group I can share with, I have a whole staff I can turn to. (Katy group 1)

– There was a trial … With the help of the home, the letters from the social worker, the change, the process, the information the court received on my progress from the home, I won my daughters again. They were supposed to be put up for adoption. (Alina, group 1)

– I’m not dependent on drugs, I don’t need to sell my body, I don’t need to steal, I don’t need to sit in prison, people don’t laugh at me, don’t insult me. I’m living like a normal person, I drink my coffee, I don’t need anything, I don’t ache, I don’t need to shoot up … (Dana, group 1)

Difficulties within the treatment setting:

Several women also found some aspects of the setting and the treatment process to be overbearing and difficult, most notable the rigidity of rules and boundaries and always having others around you:

– I was a slob for 20 years. Never had a schedule. I had a really hard time adjusting to the order here. I didn’t accept it, didn’t know it … Lot of rules, regulations. And the groups. I don’t always feel like talking. (Michal, group 3)

– It’s hard for me that this place is so small. Only 12 of us. You have to be focused [you are] always under the magnifying glass. (Sharon, group 3)

The future:

Many of the women were concerned with their future. They expressed short and long-term goals – their desire to lead a normal life, free of drugs, to get a job, to have a family, to regain custody of their children, to be independent and happy.

– I want to be in control of my own life. I try to maintain contact with my family, if they will want it. I won’t force myself on them. (Adi, Group 3)

– I want my kids with me. I don’t want to separate from my husband. I want to be with him, to be happy. I want to erase the memory – maybe someday. (Sarah, group 3)

– It’s hard for me. The thoughts don’t get me far. I just want to finish treatment and get back on my feet … For now I just need some time for myself. (Lina, group 2)

In summary, our interviews revealed that women see the home as extremely significant and supportive of their needs. The rules and boundaries set by the staff, though sometimes perceived as too rigid are mostly seen as beneficial and necessary. For a graphic summary of the central themes we identified, please refer to .

Summary and Discussion

The qualitative interviews illustrated that women at the Therapeutic Community see the setting as extremely significant. The home, staff, and the other women satisfy various needs such as identity, sense of belonging, self-value, and security. All these are gradually built via external rules that shape the boundaries of the therapeutic community, and by the therapeutic approach expressed by the staff.

Seeking treatment and the initial motivation for change is comprised of many internal and external factors.Citation46,Citation47 From the women’s accounts, it seems that the option to receive treatment in a setting that is ‘men-less’, as one woman referred to it, is extremely important and motivating. The women talked specifically about the difficulties involved with entering mixed-gender programs, where they fear the need to maintain a feminine identity, as well as having to relive previous abuse perpetrated by the men in their pasts. The idea of a women-only setting increased their sense of security, motivation, and belief that they can complete the course of treatment and remain drug free.

Several themes also emerged in the interviews regarding factors that contribute to retention in treatment. The accepting and open environment was attributed by many of the women to the fact that the setting was women-only, and therefore free of masculine pressures. This emancipation allowed for intimacy between the residents, as well as between the residents and the staff, which in turn led to more sharing (for instance of past sexual abuse) and coping with past trauma on the way to recovery. This theme is supported by previous literature, which emphasizes the importance of treatment that is focused on unique women’s needsCitation48 allowing for exposure for women who have suffered trauma and feel threatened.Citation49–Citation51

The women emphasized the significance of boundaries in the treatment process, an emphasis that is also widespread in the literature on substance abuse treatment in general. For the most part, the women saw the boundaries set by the staff as clear, yet maintained that the staff was adamant about providing a sense of solidarity and home. In other words, the women were satisfied with the setting of boundaries in a place they see and refer to as ‘a home’ rather than ‘an institution’ (as they sometimes perceive was the case in previous treatment attempts). However, several of the women also pointed to the rigidity of the boundaries and saw them as a barrier to the therapeutic process and ultimate success in treatment.

A final theme that emerged from the interviews revealed that the ability to paint a picture of the (drug-free) future is an important aspect of the treatment process and its successful completion. The women openly welcomed the opportunity to discuss their personal future in an environment that is contained, private and, above all, free of masculine perceptions and expectations. This allowed them to paint an optimistic, yet realistic, picture of the future they desire.

When the therapeutic community was established, we designed an evaluation study to follow the first few cohorts of women to enter the home. Forty-two of the 65 women who entered treatment were assessed with regard to various factors that might be associated with their retention and completion of treatment. Our study compared the 23 women who completed the entire year at the home, with the 19 who stayed for more than a month yet did not complete the program. We also followed up with 19 of the 23 completers to inquire about their lives in the community post-graduation.

Although our research focused on a comparison between women who completed treatment to those who had been in treatment at least one month but did not complete it, our results suggest that about a third of the women are not retained past the first month. This suggests the need for further research with these women, as well as implementation of additional interventions that are focused on enhancing motivation and providing support.

We found no significant differences between completers and non-completers with regard to any of the demographic or substance use variables. Though this is inconsistent with much of the international research,Citation52,Citation53 this finding is in line with previous studies conducted in Israel.Citation54,Citation55 However, we found differences between the groups with regard to various personal resources, findings also supported by additional research.Citation56–Citation59

We found that compared to non-completers, the women who completed treatment exhibited better mental health, higher levels of introverted behavior in stressful situations and a better sense of coherence, findings consistent with previous studies. Completers were also rated as less able to share emotions by the intake therapist during the initial stages of treatment, a finding the authors found quite surprising. It is important to note an inherent limitation of this study. The ability of the women to share emotions was not assessed by members of the research team and did not employ a valid and reliable questionnaire. Rather, it was assessed independent of the study by the program’s intake therapist. Since this was a program evaluation, the authors had access to this data, but no control over it. Though it is easy to attribute this statistically significant finding to this limitation or to another one of the study’s obvious limitations, its small sample size, the study’s authors believe it warrants further research and explanation.

Similar results were not encountered in the literature, yet we offer here two possible explanations for this counterintuitive finding. As one of the goals of treatment was to aid the women in identifying and expressing their emotions, it is possible that, because of their low starting point with regard to this issue, these women were able to get more out of the treatment process and feel the change more intensely. Another explanation might lie in the open and supportive setting, which may have laid the groundwork for better trust and more open communication.

Further research is needed to lend support for the findings. Perhaps, as more women graduate, a larger sample size will provide more data. As mentioned before, the therapeutic community had only 12 beds when the program evaluation was initiated, some of which remained for up to a year. As a result, data collection was a lengthy process, and the sample size was relatively small. This limits our ability to conduct further comparisons and draw additional conclusions from the results. However, despite the small size, results suggest that there is a profile of psychiatric co-morbidity, extrapunitiveness, and a lower sense of coherency that might predict risk for attrition. Women who did complete the program exhibited fewer psychiatric symptoms, intrapunitivness (aggression directed inward) and a higher sense of coherency, allowing them to cope with pressure more effectively. Based on these findings, we may be able to identify women at risk for attrition early and intervene to prevent it, for instance, by incorporating motivational interviewing techniques, cognitive therapy to increase sense of coherency, and anger management.

Results also point to the importance of long-term women-only residential treatment in increasing positive treatment outcomes. This study focused on evaluating a new program for women. A logical next step would be to compare women receiving treatment in a women-only treatment setting to those receiving treatment in a mixed-gender setting. However, the findings of our evaluation reinforce the appropriateness and potential benefits of a long-term, intimate framework for female substance abusers. Therefore, they can inform policymakers in making decisions regarding resource allocation.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge Dr Hadas Goldblat for her assistance in conducting interviews and Drs Haim Mel and Miriam Schiff for their support and encouragement. The authors also thank the anonymous reviewers for their thoughtful comments.

Finally, the authors would like to acknowledge and thank Smadar Lamberg, director of the therapeutic community, the staff and the women who participated in the study and shared their experiences and insight.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflict of interest in this work, and disclose that the first and third authors are related. No funding support was obtained for this study.

References

- HarwoodHThe economic costs of drug abuse in the United States: 1992–2002Report prepared by The Lewin Group for the Office of National Drug Control Policy (ONDCP)Bethesda, MDNational Institutes of Health2004

- National Institute on Drug Abuse [NIDA]NIDA InfoFacts: Treatment Approaches for Drug AddictionRockville, MDAuthor2006 Retrieved from: http://www.drugabuse.gov/infofacts/treatmeth.htmlAccessed June 15, 2011

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration [SAMHSA]Results from the 2008 National Survey on Drug Use and Health: National Findings (Office of Applied Studies, NSDUH Series H-36, HHS Publication No. SMA 09-4434)Rockville, MDAuthor2009

- CartwrightWSCost-benefit analysis of drug treatment services: A review of the literatureJ Ment Health Policy Econ200031112611967433

- FrenchMTSalomeHJSindelarJLMcLellanATBenefit–cost analysis of addiction treatment: Methodological guidelines and application using the DATCAP and ASIHealth Serv Res200237243345512036002

- McCollisterKEFrenchMTThe relative contribution of outcome domains in the total economic benefit of addiction interventions: A review of first findingsAddiction200298121647165914651494

- SchoriMValuation of drug abuse: A Review of current methodologies and implications for policy makingRes Soc Work Prac2011214421431

- McLellanATMeyersKContemporary addiction treatment: A review of systems problems in the treatment of adults and adolescents with substance use disordersBiol Psychiatry2004561076477015556121

- SapirYLawentalEGoldblatHMelHSchoriMLansbergSStudy Report Submitted to the Israeli Anti Drug Authority: External and Internal Factors Contributing to Treatment Retention and Positive Treatment Outcomes in Substance Abusing Women2006

- GreenfieldSFWomen and alcohol use disordersHarv Rev Psychiatry2002102768511897748

- MessinaNPWishENemesSPredictors of treatment outcomes in men and women admitted to a therapeutic communityAm J Drug Alcohol Abuse200026220722710852357

- ReedBGDrug misuse and dependency in women: the meaning and implications of being considered a special population or minority groupInt J Addict198520113623888859

- SimpsonTLMillerWRConcomitance between childhood sexual and physical abuse and substance use problems: a reviewClin Psychol Rev2002221277711793578

- BrideBESingle-gender treatment of substance abuse: Effect on treatment retention and completionSoc Work Res2001254223232

- GreenfieldSFBrooksAJGordonSMSubstance abuse treatment entry, retention, and outcome in women: A review of the literatureDrug Alcohol Depend200786112116759822

- GrellaCEGreenwellLSubstance abuse treatment for women: Changes in the settings where women received treatment and types of services provided, 1987–1998J Behav Health Serv Res200431436738315602139

- LawentalEHaifa Drug Abuse Treatment Center (HDATC) summary report for 1995–2001Haifa, IsraelRambam Medical Center2001

- AshleyOSMarsdenMEBradyTMEffectiveness of substance abuse treatment programming for women: a reviewAm J Drug Alcohol Abuse2003291195312731680

- SapirYGoldblatHLawentalESchoriMLansbergS“We see you, so we know how you feel” – drug abuse treatment in a women-only setting: The client’s perspectiveMellHHovavMGolanMAddiction, Violence and Sexual Offense: Mandatory TreatmentJerusalemCarmel Print2008139165

- StevensSArbiterNGliderPWomen residents: expanding their role to increase treatment effectiveness in substance abuse programsInt J Addict19892454254342793290

- HankePFaupelCThe implication of female risk factors for substance abuseJ Subst Abuse Treat1993105135228308935

- SowersKMEllisRAWashingtonTACurrantMOptimizing treatment attempts for substance-abusing women with children: an evaluation of the Susan B. Anthony CenterRes Soc Work Pract200212143158

- PearlinLISchoolerCThe structure of copingJ Health Soc Behav1978191221649936

- HobfollSEWalfishSLife events, mastery and depression: an evaluation of crisis theoryJ Community Psychol198614183195

- PearlinLILibermanMAMenaghanEGMullinJTThe stress processJ Health Soc Behav1981223373567320473

- Levy-KadmanSAttachment patterns, sense of control and sense of loneliness among people with visual impairment [masters thesis]Ramat Gan, IsraelBar Ilan University2000

- RosenbergMSociety and the Adolescent Self-ImagePrinceton, NJPrinceton University Press1965

- NadlerAMayselessOPeriNChemerinskiAEffects of opportunity to reciprocate and self esteem on help-seeking behaviorJ Pers1985532335

- MikulincerMOrbachIThe Body Investment Scale: construction and validation of a body experience scalePsychol Assess199810415425

- RosenzweigSThe picture association method and its application in a study of reactions to frustrationsJ Pers19451432321018305

- RosenzweigSAggressive Behavior and the Rosenzweig Picture-Frustration StudyNew YorkPraeger1978

- VeitCWareJThe structure of psychological distress and well-being in general populationsJ Consult Clin Psychol19835157307426630688

- FlorianVDroriYSense of coherence and mental health profile among women with heart diseaseMegamot [Trends]199812116121 (Hebrew)

- LoriLCharacteristics of mothers whose children are in residential community housing [masters thesis]Haifa, IsraelUniversity of Haifa1999

- Yanai-ItzhakiACognitive evaluation, coping strategies and mental welfare among mothers and fathers after their adult child with cognitive disorders (border-line intelligence or mild learning disabilities) that had left home to live in community housing [masters thesis]Tel-Aviv, IsraelTel-Aviv University2009

- AntonovskyAUnraveling the Mystery of Health: How People Manage Stress and Stay WellSan FranciscoJossey-Bass1987

- Ranz SchindlerRPredictors of dropout attributes among addicts in therapeutic communities for drug abusers: comparing Israeli-born and CIS-Born users [dissertation]Ramat Gan, IsraelBar Ilan University2008

- ChenGSocial support and a spiritual program for the personality, emotions and behavior modification of prisoners recovering substance abuse [dissertation]Ramat Gan, IsraelBar Ilan University2001

- El- BasselNCooperDKChenDRSchillingRFPersonal social networks and HIV status among women on methadoneAIDS Care19981067357499924528

- BurtRSNetwork items in the general social surveySoc Networks19846293339

- MoustakasCEPhenomenological Research MethodsThousand Oaks, CASage1994

- FontanaAFreyJHThe interview: from structured questions to negotiated textDenzinNKLincolnYSHandbook of Qualitative Research2nd edThousand Oaks, CASage2000645672

- MorganDLFocus Groups as Qualitative Research2nd edThousand Oaks, CASage1997

- PattonMQQualitative Evaluation and Research Methods2nd edNewbury Park, CASage1990

- RosenblattPCFischerLRQualitative family researchBossPGDohertyWJLaRossaRSchummWRSteinmetzSKSourcebook of Family Theories and Methods: A Contextual ApproachNew YorkPlenum Press1993167177

- CurrySWangerHEGronthousLCIntrinsic and extrinsic motivation for smoking cessationJ consult Clin Psychol19905833103192195084

- KanferFHGoldsteinAHelping People Change: A Textbook of MethodsNew YorkPergamon1986

- YeomHSGender differences in utilization, outcomes, and cost-effectiveness of substance abuse treatment among participants in an aftercare program [dissertation]Diss Abstr International Section A: Humanities and Social Sciences1987655-A

- FulliloveMTLownAFulliloveRECrack’hos and skeezers: Traumatic experiences of women crack usersJ Sex Res199229275287

- GrellaCEServices for perinatal women with substance abuse and mental health disorders: The unmet needJ Psychoactive Drugs199729167789110267

- PottiegerAEInciardiJATressellPABarriers to treatment entry for women crack usersPaper presented at the 91st Annual Meeting of the American Sociological Association1996New York

- GrellaCEJoshiVHserYIProgram variation in treatment outcomes among women in residential drug treatmentEval Rev200024436438311009864

- SimpsonDDJoeGWMotivation as a predictor of early dropout from drug abuse treatmentPsychotherapy1993302357368

- LawentalEMichaeliAChazanHPredictors of success in programs for home based detoxification of drug addictsSociety and Welfare1983132117128

- LevinsonDThree detoxification methods for withdrawal and assessment of results one year after treatmentSociety and Welfare199818141159

- BurgdorfKChenXWalkerTPorowskiAHerrellJMThe prevalence and prognostic significance of sexual abuse in substance abuse treatment of womenAddict Disord Their Treat200431113

- De LeonGMelnickGKresselDMotivation and readiness for therapeutic community treatment among cocaine and other drug abusersAm J Drug Alcohol Abuse19972321691899143632

- DodgeRSindelarJSinhaRThe role of depression symptoms in predicting drug abstinence in outpatient substance abuse treatmentJ Subst Abuse Treat200528218919615780549

- KellyPJBlacksinBMasonEFactors affecting substance abuse treatment completion for womenIssues Ment Health Nurs200122328730411885213