Abstract

Background

There are limited data available regarding long-term survival and its predictors in cases of in-hospital cardiac arrest (IHCA) in which patients receive cardiopulmonary resuscitation.

Purpose

The objectives of this study were to determine the 1-year survival rates and predictors of survival after IHCA.

Patients and methods

Data were retrospectively collected on all adult patients who were administered cardiopulmonary resuscitation from January 1, 2013 to December 31, 2014 in Srinagarind Hospital (Thailand). Clinical outcomes of interest and survival at discharge and 1 year after hospitalization were reviewed. Descriptive statistics and survival analysis were used to analyze the outcomes.

Results

Of the 202 patients that were included, 48 (23.76%) were still alive at hospital discharge and 17 (about 8%) were still alive at 1 year post cardiac arrests. The 1-year survival rate for the cardiac arrest survivors post hospital discharge was 72.9%. Prearrest serum HCO3<20 meq/L, asystole, urine <800 cc/d, postarrest coma, and absence of pupillary reflex were predictors of death.

Conclusion

Only 7.9% of patients with IHCA were alive 1 year following cardiac arrest. Prearrest serum HCO3<20 meq/L, asystole, urine <800 cc/d, postarrest coma, and absence of pupillary reflex were the independent factors that predicted long-term mortality.

Introduction

In-hospital cardiac arrest (IHCA) is defined as cessation of cardiac activity, confirmed by the absence of signs of circulation, in a hospitalized patient who had a pulse at the time of admission.Citation1 The estimated incidence of this condition in previous reports is about 1.6 per 1,000 admissions in the UK and 17.5 per 1,000 admissions in People’s Republic of China.Citation2,Citation3 Cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) has been used as an attempt to intervene in this process.Citation4 The outcome of CPR, however, remains poor, even if it is performed in a hospital where there are trained staff and equipment available. Previous reports have revealed the return of spontaneous circulation (ROSC) and survival rates to discharge of IHCA to be 15%–60% and 6.6%–37%, respectively.Citation2–Citation11 These vary due to diversity in terms of age, comorbidities, and study populations.Citation2,Citation3,Citation12 No single factor predicted any of those short-term outcomes. They were actually associated with multiple factors – including age, gender, race, ethnicity, preexisting conditions, event interval and duration to perform CPR, type of arrhythmia, hospital location, early defibrillation, and postresuscitation care.Citation2,Citation3,Citation11–Citation13 There are several morbidity scores that are used such as the prearrest morbidity scores, the prognosis after resuscitation score, and the modified prearrest morbidity scores index.Citation12,Citation14,Citation15 However, these scores have demonstrated poor predictive performance, with sensitivities ranging from 20% to 30%.Citation12,Citation14,Citation15 The conse quences of CPR among survivors with prolonged hypoxemia are related to functional and cognitive decline, resulting in burdens on caregivers and reduced quality of life.Citation13 Thus, it is crucial that health-care teams and families consider the rational and moral aspects of the decision to perform CPR in patients with cardiac arrest.Citation11–Citation13,Citation16

Even though patients with cardiac arrest usually survive to discharge, they have poorer long-term survival rates.Citation4,Citation17 Long-term outcome following IHCA has been studied as a better prognostic predictor than short-term outcome.Citation18 Unfortunately, there has been limited research regarding this outcome and its predictors. Existing reports showed absolute survival rates at 1 year to be only 5%–12%.Citation4,Citation17 The factors associated with long-term survival were age, cardiac rhythm, and comorbidities.Citation4 Older adults who identified as black, women, and with extensive neurologic deficits were readmitted at 1 year after hospital discharge at a greater rate than other older adults.Citation18 Data about the epidemiology and prognostic factors for short- and long-term survival in Thailand are limited. Therefore, the primary objective of this study was to assess survival rates for IHCA survival at 1 year after cardiac arrest. The secondary objectives were to determine predictors associated with death at 1 year following cardiac arrest in long-term survival among patients with IHCA.

Methods

Study setting and patient population

This is a retrospective study of patients who were aged 18 years and older and had IHCA and in whom CPR was attempted at Srinagarind Hospital from January 1, 2013 to December 31, 2014. Patients were excluded if they had subsequent episodes of cardiac arrest during the same hospital admission or if their medical records were unavailable.

Data collection

Demographic and clinical variables prearrest, intra-arrest, and postarrest were obtained from the CPR unit’s cardiac arrest records and civil registration records.

They included age, sex, type of ward, length of stay, reason for admission, comorbid diseases, prearrest cardiac rhythm, homebound status, use of mechanical ventilation, whether the arrest was witnessed, pre- and postarrest mental status, latest blood chemistry (blood urea nitrogen/creatinine, electrolytes) before cardiac arrest, duration of CPR, total dosage of epinephrine, presence of pupillary reflex postarrest, ROSC, and survival at discharge, 7 days after discharge, 30 days, 6 months, and 1 year after cardiac arrest. Survival at discharge might not reflect the true survival status due to the fact that patients in this population were likely to return home if their chances of survival were low. We, thus, collected data regarding survival at 7 days postdischarge.

Definition

Sepsis was defined based on the Society of Critical Care Medicine/the European Society of Intensive Care Medicine task force as life-threatening organ dysfunction caused by a dysregulated host response to infection.Citation19

Pneumonia was defined as an infection of pulmonary parenchyma by various pathogens, not a single disease. The following clinical categories were identified: community-acquired, nosocomial, and aspiration pneumonia.Citation20

Statistical analysis

Demographic data and clinical variables were analyzed using descriptive statistics and were presented as percentage, mean, and SD. If the distribution of these data did not conform to normal distribution, medians and interquartile ranges were used instead. A Kaplan–Meier plot was used to estimate the survival of the study population. Predictors of survival at 1 year after cardiac arrest were analyzed using univariate analysis. Crude hazard ratio and 95% CI were used to show the level of association. Factors were then entered into a multiple Cox regression model. An initial multivariable model and then purposeful selection with backward elimination were used to analyze the outcomes. Assessment of survival model adequacy was divided into five steps. The first step was verification of statistical significance of covariates. Then, Cox proportional hazard model-specific assumptions were examined. Poorly fit and influential subjects were identified in the next step. Finally, an overall goodness-of-fit test was performed to determine of the final models. A p-value <0.05 according to a partial likelihood ratio test was considered to indicate statistically significant differences. Strength of association was reported as adjusted hazard ratios and their 95% CI. All data analysis was carried out using STATA version 10.0 (StataCorp, College Station, TX, USA).

Ethical approval was provided by the Khon Kaen University Faculty of Medicine ethics committee as instituted by the Helsinki Declaration. The reference number was HE581210. Since the study design was a retrospective chart review, patient consent to review their medical records was not required. Anonymous patients’ information was used for patients’ privacy protection.

Results

Characteristics of the study population and survival time

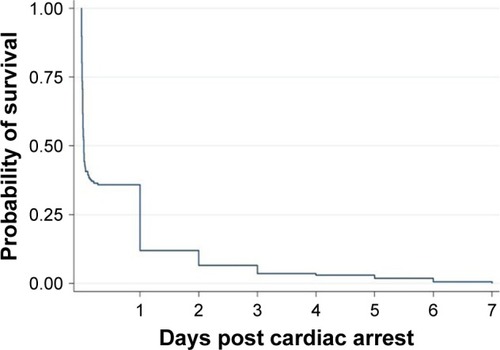

There were 278 cardiac arrest patients who received CPR during the study period which included both in- and out-hospital cardiac arrest. A total of 202 patients who received cardiopulmonary resuscitation met the inclusion criteria. shows the demographics and survival times of the cardiac arrest patients. The median age of the patients was 59 years, and the number of women was slightly higher than that of men. The majority of the patients were in the general ward, followed by the intensive care unit. Infection was the top reason for admission. About 40% of patients had a history of hypertension and about 30% had diabetes. Pulseless electrical activity was the most frequent cause of arrest, followed by asystole and ventricular tachycardia/ventricular fibrillation (VT/VF). The median duration of CPR was 15 minutes. Approximately 60% of patients had ROSC following CPR, about 24% survived to discharge from the hospital and 8% survived to 1 year. The 1-year survival rate of the arrest survivors post hospital discharge was 72.9% (35 out of 48 cases). demonstrates the Kaplan–Meier curve of survivors at 7 days after cardiac arrest.

Table 1 Baseline data and survival time of the study population

Predictors of death at 1 year after cardiac arrest

Univariate analysis found that patients with comorbid hematologic malignancy and dementia, urine <800 cc/d, initial coma, hyponatremia, and serum HCO3<20 meq/L had increased risk of death, whereas factors such as VF/VT and other cardiac rhythms apart from asystole and pulseless electrical activity at presentation as opposed to asystole were associated with decreased mortality. In terms of intra-and postarrest factors, higher epinephrine dosage, coma at 72 hours postarrest, and absence of pupillary reflex increased risk of death, whereas infection appeared to be a protective factor ().

Table 2 Factors associated with death at 1 year after cardiac arrest using univariate analysis

Final models were developed using multivariate analysis. Interaction effect and assessment of model adequacy to test proportional hazard assumption were performed. Influential and poorly fit subjects were identified. An overall goodness-of-fit test was then performed. Model A was the best-fit model that was used for prearrest prediction. The model included three factors: serum HCO3<20 meq/L, asystole, and urine <800 cc/d. Model B, which included both pre- and postarrest factors, was the best-fit model that was used for predicting mortality at 1 year after cardiac arrest. It included coma at 72 hours postarrest and absence of pupillary reflex, along with the three factors listed above ().

Table 3 The best-fit model for factors associated with death at 1 year post cardiac arrest using multivariate analysis

Discussion

The survival rates after resuscitation and discharge from the hospital in this study were comparable to the previous reports, among which ROSC varied from 15% to 60% and survival at discharge varied from 6.6% to 37%.Citation1,Citation2,Citation4–Citation11 However, in this report, these figures were rather low, which was probably due to the use of CPR in patients who had poor prognoses, such as those with metastatic cancer or other terminal illnesses. As shown above, around one-third of the patients had malignancy or sepsis. In addition, survival at discharge in this study might not reflect the true survival rates, most patients with low chances of survival opted to return home, as mentioned above. Survival at 7 days after discharge from the hospital was more likely to reflect the actual short-term outcome. Nevertheless, the figures (about 18%) were similar to those from previous reports.Citation1,Citation2,Citation7–Citation11 The period after discharge in which patients were the most vulnerable in this study was the first 7 days. According to previous reports, most patients die within 30–90 days after discharge.Citation17,Citation18 Differences in patient characteristics could influence the period in which patients are most susceptible. In this study, a greater proportion of patients were admitted due to noncardiac causes and nonshockable cardiac rhythm than in previous reports.Citation17,Citation18 These two factors have been reported as independent predictors of death at hospital discharge in several studies.Citation12,Citation21,Citation22

This study is the first report from Asia to examine the long-term outcomes of IHCA patients after CPR. Only 8% of patients survived. The results of long-term follow-ups after IHCA may more accurately represent the prognosis of the patients than status at discharge.Citation17,Citation18 Of the patients who survived, the survival rate at 1 year post cardiac arrest was 72.9%, which was higher than the rates found in the majority of previous studies (58.5%–68%).Citation4,Citation17,Citation18 One study, however, reported a survival rate of 86%.Citation6 A possible explanation for this is that the studies with lower survival rates were conducted in older patients, as several studies have found age to be a predictor of death.Citation9,Citation12,Citation21 The study that had highest survival rate included both younger and older adults.Citation6 This may have meant the population was positively skewed toward having better a survival rate.

This study showed that both prearrest and postarrest factors were the important predictors after multivariate analysis. The majority of previous studies focused on factors associated with short-term survival, and there were few that included long-term factors.Citation8,Citation12,Citation21,Citation22 The varying results of previous reports make it clear that the predictors of IHCA are not universal.Citation4,Citation9,Citation18 Some studies have shown advanced age and longer duration of CPR to be associated with mortality.Citation4,Citation9 The results of this study, however, support the findings that prearrest cardiac rhythm, comorbid conditions, and significant neurologic disability are related to survival.Citation4,Citation9 Consistent with several reports, patients with VF/VT had better prognoses than those with asystole,Citation2,Citation3,Citation22 as asystole is typically a terminal arrest, meaning that chances of recovering are low. VF/VT reflects early arrest and can be treated promptly with defibrillation.Citation2,Citation22 Low serum HCO3 indicates acidosis, which could be the result of a variety of serious illnesses, such as lactic acidosis from sepsis and renal failure, which are factors know to be associated with mortality.Citation4,Citation9,Citation12,Citation23 Renal failure is also a frequent cause of mortality in hospitalized patients, which explains the association decreased urine volume with mortality found in this study.Citation17 This study did not find an association between age and long-term outcomes. This may be explained by the differences in study population mentioned previously. The median age of patients in this study was 59 years (compared to that of 70 years in a previous study).Citation9 Furthermore, differences in study setting could be as issue as that prior study included only intensive care unit patients, in whom disease is likely to be more severe. In addition, patients with comorbid hematologic malignancy and dementia showed significant association with death at 1 year. However, they failed to show the association when using multivariate analyses.

According to our results, Model A is useful in predicting patient prognosis before they receive CPR in order to avoid futile resuscitation, and Model B is helpful in determining prognosis prior to hospital discharge as they use common factors in clinical practice. Simple risk models to predict long-term mortality with good discrimination should be then developed. Information regarding prognosis should be shared with allied health care members, family members, and the patient him/herself (if possible) as a part of the decision-making process on the basis of patient center to abstain from prolonged inevitable death.Citation12 Further study regarding the validation each model’s usefulness is advised.

There were some limitations in this study. First, it is a single-setting analysis of long-term survival following IHCA. Therefore, it might not be generalizable to different settings. Second, actual functional status, such as neurological outcomes, activities of daily living, and quality of life post cardiac arrest, was not measured in this study. Third, due to the nature of retrospective study, data from charts or CPR records, such as known predictors of mortality (like activities of daily living), might be lost or incomplete. Lastly, the majority of the patients died in the first 7 days post cardiac arrest. Factors associated with long-term survival might not represent the actual fact while investigating periarrest factors in patients who survived to hospital discharge might be a better approach.

Conclusion

IHCA has poor long-term outcomes. Only about 7.9% of patients survived for 1 year after cardiac arrest. Survival at discharge might not be a good endpoint to determine the effectiveness of CPR. Prearrest factors (serum HCO3<20 meq/L, asystole and urine <800 cc/d) and postarrest factors (coma at 72 hours postarrest and absence of pupillary reflex) were independent outcome predictors for long-term mortality. Further studies to develop practical predictive models and validate the performance of these models are recommended for using as part of the decision-making process with regard to CPR, which should take into account individual outcomes and patient preference.

Acknowledgments

We would like to acknowledge Dylan Southard (Research Affairs, Faculty of Medicine, Khon Kaen University, Thailand) for editing the manuscript. This manuscript was funded by the Sleep Apnea Research Group (Khon Kaen University, Thailand) and the Thailand Research Fund (number IRG 5780016).

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- TirkkonenJHellevuoHOlkkolaKTHoppuSAetiology of in-hospital cardiac arrest on general wardsResuscitation2016107192427492850

- NolanJPSoarJSmithGBIncidence and outcome of in-hospital cardiac arrest in the United Kingdom National Cardiac Arrest AuditResuscitation201485898799224746785

- ShaoFLiCSLiangLRIncidence and outcome of adult in-hospital cardiac arrest in Beijing, ChinaResuscitation2016102515626924514

- BloomHLShukrullahICuellarJRLloydMSDudleySCJrZafariAMLong-term survival after successful in hospital cardiac arrest resuscitationAm Heart J2007153583183617452161

- SongWChenSLiuYSMoDFLanBQGaoYSA prospective investigation into the epidemiology of in-hospital cardiopulmonary resuscitation using the international Utstein reporting styleHong Kong J Emerg Med2011186391396

- FredrikssonMAuneSThorenABHerlitzJIn-hospital cardiac arrest – an Utstein style report of seven years experience from the Sahlgrenska University HospitalResuscitation20066835135816458407

- LidhooPEvaluating the effectiveness of CPR for in-hospital cardiac arrestAm J Hosp Palliat Care201330327928222669933

- KrittayaphongRSaengsungPChawaruechaiTYindeengamAUdompunturakSFactors predicting outcome of cardiopulmonary resuscitation in a developing country: the Siriraj cardiopulmonary resuscitation registryJ Med Assoc Thai200992561862319459521

- KutsogiannisDJBagshawSMLaingBBrindleyPGPredictors of survival after cardiac or respiratory arrest in critical care unitsCMAJ2011183141589159521844108

- ChanJCWongTWGrahamCAFactors associated with survival after in-hospital cardiac arrest in Hong KongAm J Emerg Med201331588388523478113

- LimpawattanaPSiriussawakulAChandavimolMNational data of CPR procedures performed on hospitalized Thai older population patientInt J Gerontol2015926770

- EbellMHAfonsoAMPre-arrest predictors of failure to survive after in-hospital cardiopulmonary resuscitation: a meta-analysisFam Pract201128550551521596693

- ChangWHHuangCHChienDKSuYJLinPCTsaiCHFactors analysis of cardiopulmonary resuscitation outcomes in the elderly in TaiwanInt J Gerontol200931625

- BowkerLStewartKPredicting unsuccessful cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR): a comparison of three morbidity scoresResuscitation1999402899510225281

- CohnEBLefevreFYarnoldPRArronMJMartinGJPredicting survival from in-hospital CPR: meta-analysis and validation of a prediction modelJ Gen Intern Med1993873473538410394

- MohrMKettlerDEthical aspects of resuscitationBr J Anaesth19977922532599349135

- FeingoldPMinaMJBurkeRMLong-term survival following in-hospital cardiac arrest: a matched cohort studyResuscitation201699727826703463

- ChanPSNallamothuBKKrumholzHMLong-term outcomes in elderly survivors of in-hospital cardiac arrestN Engl J Med2013368111019102623484828

- SingerMDeutschmanCSSeymourCWThe third international consensus definitions for sepsis and septic shock (sepsis-3)JAMA2016315880181026903338

- LevisonMEPneumonia, including necrotizing pulmonary infections (lung abscess)BraunwaldEFauciASHauserSLLongoDLKasperDLJamesonJLHarrison’s Principles of Internal Medicine15th edNew York, NYMcGraw-Hill200114751484

- TaffetGETeasdaleTALuchiRJIn-hospital cardiopulmonary resuscitationJAMA198826014206920723270334

- BrindleyPGMarklandDMMayersIKutsogiannisDJPredictors of survival following in-hospital adult cardiopulmonary resuscitationCMAJ2002167434334812197686

- SuraseranivongseSChawaruechaiTSaengsungPKomoltriCOutcome of cardiopulmonary resuscitation in a 2300-bed hospital in a developing countryResuscitation200671218819316987585