Abstract

Mepolizumab is an anti-interleukin-5 (IL-5) humanized monoclonal antibody that binds to free IL-5. It induces bone marrow eosinophil maturation arrest and decreases eosinophil progenitors and subsequent maturation in the blood and bronchial mucosa. Its use has been extensively studied in severe eosinophilic asthma at a dose of 100 mg subcutaneously (SC) every 4 weeks and, more recently, in other hypereosinophilic syndromes. Eosinophilic granulomatosis with polyangiitis (EGPA) is an eosinophilic vasculitis that may involve multiple organs. Characteristic clinical manifestations are asthma, sinusitis, transient pulmonary infiltrates and neuropathy. Among the numerous pathways involved in the pathogenesis of EGPA, the Th-2 phenotype has a main role, as suggested by the prominence of the asthmatic component, in triggering the release of key cytokines for the activation, maturation and survival of eosinophils. In particular, IL-5 is highly increased in active EGPA and its inhibition can represent a potential therapeutic target. In this scenario, mepolizumab may play a therapeutic role. After some positive preliminary observations on the use of mepolizumab in small case series of EGPA patients with refractory or relapsing disease despite standard of care treatment, a randomized controlled trial was published in 2017. Mepolizumab at a dose of 300 mg administered by SC injection every 4 weeks proved effective in prolonging the period of remission of the disease, allowing for reduced steroid use. The positive results of this study, which met both of the primary endpoints, led to the approval in the USA of mepolizumab in adult patients with EGPA by the Food and Drug Administration in 2017. Therefore, mepolizumab can be officially considered as an add-on therapy with steroid-sparing effect in cases of relapsing or refractory EGPA. However, the most appropriate dose and duration of therapy still need to be determined. Future studies on larger multinational populations with prolonged follow-up are warranted.

Introduction

Mepolizumab has recently been proposed as an anti-interleukin-5 (IL-5) agent for the treatment of severe eosinophilic asthma.Citation1 However, its use has been explored in other diseases that share some pathogenic mechanisms with eosinophilic asthma, including eosinophilic granulomatosis with polyangiitis (EGPA), with interesting results.Citation2

The aim of this review is to evaluate the rationale and the current evidence on the use of mepolizumab in EGPA.

A search of relevant medical literature in the English language was conducted in Medline/PubMed, EMBASE, Cochrane and ClinicalTrials.gov databases, including observational and interventional studies, up to June 2018. Keywords used to perform the research were MEPOLIZUMAB AND (EGPA OR Eosinophilic Granulomatosis with Polyangiitis OR Churg–Strauss OR vasculitis OR hypereosinophilic syndrome OR HES OR asthma) or PATHOGENESIS AND (EGPA OR Eosinophilic Granulomatosis with Polyangiitis OR Churg–Strauss). Studies targeting children, and editorials, narrative and conference abstracts, were excluded.

From Churg–Strauss syndrome to EGPA

EGPA was first described in 1951 by J. Churg and L. Strauss as a form of disseminated necrotizing vasculitis with extravascular granulomas that occurred exclusively among patients with asthma and tissue eosinophilia.Citation3 Initially it was called “allergic angiitis with granulomatosis”, as the histology seen in the first patients showed a necrotizing vasculitis, eosinophilic infiltrates in tissues and granulomas. However, since it is rare to identify the three lesions in the same patient, the diagnosis of EGPA is based primarily on clinical parameters. In 1984, Lanham et al proposed three diagnostic criteria that allowed the diagnosis of EGPA from a clinical point of view.Citation4 They proposed that patients with EGPA should be characterized by the presence of asthma, eosinophilia and vasculitic involvement of two or more organs. However, this clinical definition has been criticized over time for several reasons: first of all, asthma can follow and not precede the vasculitic phase; secondly, eosinophilia can sometimes fluctuate and disappear, both spontaneously and after corticosteroid treatment; and, finally, vasculitis may be difficult to confirm, despite some typical clinical manifestations, without a biopsy. Therefore, specific diagnostic criteria changed from the first observations to most recent consensus conferences ().Citation4–Citation6 Despite being the most commonly used, the criteria proposed by the American College of Rheumatology (ACR) in 1990 were developed not for diagnostic purposes but for classification, and should thus be used only in the presence of histologically proven vasculitis, otherwise they lose specificity and sensitivity.Citation7 Since the histological diagnosis of vasculitis is not possible in all patients, for example when the severity of the disease does not allow the execution of a biopsy, Watts et al proposed and validated an algorithm for the diagnosis and classification of anti-neutrophil cytoplasm antibody (ANCA)-associated vasculitis ().Citation6

Table 1 Evolution of diagnostic criteria for EGPA

In their original description in 1951, Churg and Strauss reported 13 cases that had been labeled as polyarteritis nodosa.Citation3 The authors, using the histological criteria of necrotizing vasculitis, tissue infiltration from eosinophils and extravascular granulomas, reclassified these cases in the new clinical entity that we are considering.Citation3 The first International Chapel Hill Consensus Conference (CHCC) on the nomenclature of systemic vasculitis in 1994 defined EGPA as “a granulomatous type inflammation rich in eosinophils involving the respiratory tract, associated with necrotizing vasculitis affecting small and medium-sized vessels, asthma and eosinophilia”.Citation8

The revised International CHCC in 2012 recommended replacing the eponymous “Churg–Strauss angiitis” with “eosinophilic granulomatosis with polyangiitis (EGPA)”, with the aim of focusing on the histopathology of the disease.Citation9 Despite proposing the same diagnostic criteria as the ACR in 1990,Citation5 the 2012 CHCC reported for the first time the presence of ANCAs in EGPA, particularly in patients with glomerulonephritis.Citation9

Our knowledge of EGPA has recently improved. ANCAs have been found in a significant proportion of EGPA patients (30%–40%),Citation10,Citation11 and EGPA has therefore been included in the spectrum of ANCA-associated vasculitis (AAV) together with granulomatosis with polyangiitis (GPA), formerly Wegener’s granulomatosis, and microscopic polyangiitis (MPA).Citation8 In EGPA, ANCAs typically show a perinuclear fluorescence labeling pattern (p-ANCA) at immunofluorescence, associated with elevated neutrophil myeloperoxidase (MPO) antibodies on enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) analysis. The clinical presentation of ANCA-positive patients differs significantly from that of ANCA-negative patients, since in the former, vasculitic symptoms, such as glomeru-lonephritis, mononeuritis and alveolar hemorrhage, are more frequent, while in the latter, cardiomyopathy prevails.Citation11–Citation13 This observation led to the hypothesis that EGPA could be divided into different clinical and pathophysiological subtypes, which would also imply a different pharmacological management. However, this remains a hypothesis to be explored.Citation14

EGPA is the least common among AAVs and may affect virtually any organ, but is often of a phasic nature. Classically, EGPA develops in three sequential phases: prodromal phase, eosinophilic phase and vasculitic phase.Citation15 These phases often overlap and are rarely clearly distinguishable. Most patients report non-specific constitutional symptoms in the course of the disease. These include fever, fatigue, arthralgia and weight loss. Some patients also develop respiratory and cardiovascular involvement, followed by peripheral neurological and cutaneous manifestations.Citation8 EGPA is a disease that has a borderline classification among primary systemic vasculitisCitation9 and hypereosinophilic disorders.Citation4,Citation16 Within this dual categorization, EGPA is classified among the vasculitis of small vessels and hypereosinophilic syndromes (HES).Citation4 Both inflammation of the vessels and eosinophilic proliferation are thought to contribute to organ damage, but clinical presentations are heterogeneous and the respective roles of vasculitis and hypereosinophilia in the disease course are not well understood. More commonly, the diagnosis of EGPA is based on the onset of vasculitic manifestations (such as the appearance of multiple mononeuritis, purpura and glomerulonephritis) and eosinophilia, in a patient who previously suffered from asthma. However, some patients can develop either asthma or eosinophilia at the same time as the vasculitis and sometimes even, albeit rarely, only in the weeks following its onset.Citation17 More rarely (in less than 10% of cases), asthma may not be present.Citation10,Citation18

EGPA pathogenesis: what do we know?

The pathogenesis of EGPA is not completely clear. The disease is probably the result of complex interactions in which genetic and environmental factors lead to an inflammatory response whose main actors are eosinophils and T and B lymphocytes.Citation14 Although most cases of EGPA are idiopathic, some possible triggers have been identified; in particular, some immunogenic factors may confer greater susceptibility to the development of the disease. The association between EGPA and major histocompatibility complex (human leukocyte antigen [HLA]), particularly HLA-DRB1 04 and 07, and with HLA-DRB4, has been widely demonstrated.Citation19–Citation21 The HLA class II restriction repertoire suggests a strong activation by CD4+ T lymphocytes, probably triggered by allergens or antigens. This is not the only clue indicating that activation of T lymphocytes plays an important role in the pathogenesis of EGPA. They are present in most organic lesions and are the main component in some of them, such as in peripheral neuropathy. Furthermore, serum T-cell activation markers, such as IL-2r, are increased during the active phase of the disease.Citation22 T-cell receptors show a limited repertoire suggesting an oligoclonal expansion, which is in line with the hypothesis of an antigen-driven disease.Citation23

Various environmental factors have been involved in the development of EGPA. These include infectious agents (eg, Actinomyces), drugs (eg, sulfonamides, macrolides, quinine and carbamazepine), vaccinations and, in one report, silicate exposure.Citation24–Citation30 However, different studies have already demonstrated the safety of vaccines during the course of systemic inflammatory diseases including EGPA.Citation31 The onset of EGPA has also been associated with the use of anti-asthmatic drugs, particularly leukotriene receptor inhibitors, including montelukast and zafirlukast, and, more recently, the use of omalizumab, an anti-IgE monoclonal antibody for the treatment of severe asthma.Citation32–Citation35 Nevertheless, it is now believed that these drugs do not cause EGPA but rather, since they allow a better control of asthma, permit a reduction or suspension of systemic steroids, which would lead to the unblinding of EGPA that was already present but maintained at a subclinical level.Citation36

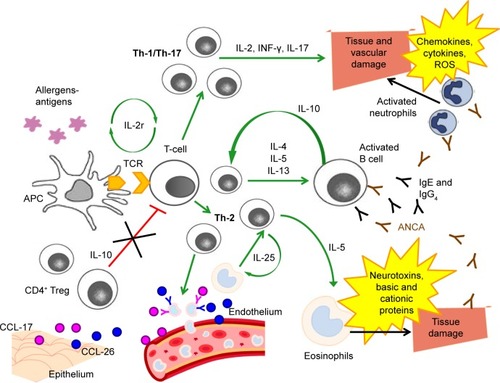

EGPA is a disease mediated mainly by the Th-2 response, as suggested by the prominence of the asthmatic and eosinophilic components.Citation37 This enhanced Th-2 response is also favored by high circulating levels of IL-25, which have been found to be related to EGPA activity phases.Citation38 The pathophysiology of EGPA is summarized in .

Figure 1 Pathophysiology of EGPA.

The activated Th-2 phenotype triggers the release of key cytokines for the activation, maturation and survival of eosinophils, such as IL-4, IL-5 and IL-13.Citation39,Citation40 In particular, IL-5 is highly increased in active EGPA and its inhibition can represent a potential therapeutic target.Citation41–Citation43 High eosinophil levels are an integral part of the diagnosis of EGPA, and have a cytotoxic and pro-coagulant effect that may cause the development of cardiovascular and cerebrovascular complications in patients with any type of hypereosinophilic syndrome, including EGPA.Citation14,Citation44–Citation47 Eosinophil products, including basic and cationic proteins and neurotoxins, are cytotoxic and can induce direct damage to the tissues.Citation48 Furthermore, eosinophils, despite being considered effector cells, may also act as immunoregulatory cells.Citation14 There is probably an additive cross-talk between T lymphocytes and eosinophils: high concentrations of IL-25, mainly produced by eosinophils and detected in serum from EGPA patients, induce T cells to produce cytokines that stimulate the Th-2 and eosinophilic response, resulting in a positive feedback mechanism.Citation49

Together with IL-5 and IL-25, IL-10 is an important molecule for the activation of the Th-2 pathway: the presence of a single-nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) of the gene that codes for IL-10, in patients with EGPA who are ANCA negative, is associated with the IL10.2 haplotype of the IL-10 promoter gene, a condition that leads to an increase in IL-10 production.Citation50 The increase in IL-10 leads to a greater Th-2 response and an increase in IgG4 levels. In particular, the IgG4 antibody level can be measured in the serum of patients with active disease and correlates with both the number of affected organs and the phase of disease activity.Citation51 Serum IgG4 levels and the IgG4/IgG ratio are increased in patients with active EGPA, compared to healthy individuals, people with GPA and asthmatic patients.

However, clinical manifestations of EGPA cannot be explained only through an increased Th-2 response.Citation52 Endothelial and epithelial cells can also amplify the immune response by producing chemokines, such as eotaxin-3 (CCL-26) and chemokine-17 (CCL-17), which attract eosinophils and determine the chemotaxis to the sites of inflammation.Citation14,Citation41,Citation48 Eotaxin-3 is elevated in serum samples from active EGPA patients and significantly correlates with eosinophil count, total IgE and acute-phase parameters.Citation39,Citation53

Furthermore, Th-1- and Th-17-type immune responses and the regulatory T cells (Tregs) also play a role in the pathogenesis of EGPA.Citation38,Citation54 Reduced levels of CD4+ Tregs, which have a protective role towards the development of autoimmune diseases, were observed in patients with EGPA,Citation52,Citation55,Citation56 and the percentages of circulating Tregs were lower during the phases of disease activity compared to the phases of quiescence.Citation14,Citation54 T lymphocytes from patients with EGPA produce, after stimulation in vitro, a large amount of interferon-gamma (IFN-γ), which increases the Th-1-type immune response, suggesting a link between humoral and cell-mediated immunity and eosinophils.Citation57

The interconnection between eosinophils and lymphocytes is well exemplified in granulomas, the most specific EGPA anatomopathological lesions, which consist of a nucleus of necrotic eosinophilic material surrounded by lymphocytes arranged to form a wall associated with multi-nucleated giant epithelioid cells.Citation3,Citation8

Finally, ANCAs also have a role in the pathogenesis, as well as in the diagnosis, of EGPA. The endothelial damage induced by these autoantibodies, together with the infiltration of eosinophils, is one of the most important mechanisms underlying the histological damage typical of the disease. The pathogenic effects of anti-MPO ANCAs are primarily related to their ability to cause neutrophil activation, degranulation with release of cytoplasmic granules, containing reactive oxygen species, cytokines, chemokines and adhesion molecules, and subsequent vascular damage.Citation58,Citation59

Rationale for using mepolizumab in EGPA

Mepolizumab is an anti-IL-5 humanized monoclonal antibody that binds to free IL-5 with high specificity and affinity, thus preventing the association between IL-5 and IL-5 receptors on the surface of eosinophils and basophils.Citation1 It induces bone marrow eosinophil maturation arrest and decreases eosinophil progenitors and subsequent maturation in the blood and bronchial mucosa.

Mepolizumab has been extensively used in asthmatic patients. Since 2003, numerous trials have been published on the use of mepolizumab in different types of asthma, from mild-to-moderate to steroid-dependent and severe eosinophilic asthma. Although studies in non-severe asthmatics did not show an improvement in symptoms and pulmonary function tests (PFTs), only a reduction in plasma and airway eosinophils,Citation60–Citation62 trials on severe eosinophilic asthmatics showed a reduction in the number of exacerbations and an improvement in quality of life and PFTs, besides a glucocorticoid-sparing effect.Citation63–Citation68 Preferred doses of mepolizumab were 750 mg intravenously (IV) every 4 weeks or 100 mg subcutaneously (SC) every 4 weeks. Subcutaneous preparation is currently the recommended method of administration, based on studies that showed higher serum levels of immunoglobulins when administered SC compared with IV infusion.Citation69 The safety profile of mepolizumab also seems good. Based on the aforementioned trials and on post-marketing surveillance, the risk of anaphylaxis was estimated to be below 1%, while the most commonly reported adverse events included headache (17%–20%), pharyngolaryngeal pain (14%–17%), nasal ulceration and somnolence.Citation70 Injection-site reactions were more frequent in the SC (9%) than in the IV forms or placebo (3%).Citation67

On the basis of the positive results reported on severe eosinophilic asthma, mepolizumab use has been extended to eosinophilic chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) and HES.Citation71,Citation72

In the first case, a pilot study on 18 COPD patients with sputum eosinophilia showed in the mepolizumab group a significant reduction of plasma and sputum eosinophils and a trend towards improvement in PFTs and quality of life questionnaires compared to placebo.Citation71 However, there was no statistically significant difference in the number of exacerbations during the 6-month study period. In contrast, in the study by Pavord et al on 462 patients with COPD and eosinophilic phenotype, mepolizumab at a dose of 100 mg SC was associated with a lower annual rate of moderate or severe exacerbations than placebo.Citation72

In the second case, preliminary studies with mepolizumab proved effective in reducing peripheral eosinophil counts in patients with different HESs, regardless of baseline IL-5.Citation73–Citation75 HESs are mainly treated with long-term corticosteroids, and therefore the development of steroid-related side effects and refractoriness to usual medication may occur. To address these issues, mepolizumab has been considered as possible steroid-sparing agent or second line therapy. Rothenberg et al demonstrated that mepolizumab was well tolerated and significantly reduced steroid dosing, with maintenance of clinical stability in non-EGPA FIP1L1 PDGFRA2-negative HES.Citation76 The long-term positive outcomes and safety of mepolizumab in HES have also been confirmed by more recent studies.Citation77,Citation78

The experience with the aforementioned hypereosinophilic diseases and the pathogenesis of EGPA, which involves eosinophils and their degranulation products, including IL-5, provide a rational approach to the use of mepolizumab in EGPA.

Mepolizumab in EGPA: current available evidence

The first case of successful use of mepolizumab in EGPA was reported in 2010.Citation79 A young woman affected by EGPA with a history of lung and cardiac involvement, who experienced disease relapse and adverse events despite treatment with multiple drugs (systemic steroids, methotrexate, IFN-α, cyclophosphamide, IV immunoglobulin, azathioprine and etoposide), was treated with mepolizumab 750 mg IV monthly. After 1 month, she achieved complete control of asthma symptoms and normalization of eosinophilic count and, after 2 months, regression of lung opacities. EGPA activity, which relapsed after mepolizumab discontinuation, was controlled after reinitiation of monthly mepolizumab infusion and low-dose steroids.Citation79

After this first successful report, other studies on mepolizumab application in EGPA were conducted, as summarized in .Citation43,Citation80–Citation82

Table 2 Summary of the main observational studies and RCTs on the use of mepolizumab in EGPA

In an open-label pilot study conducted on seven EGPA patients under chronic corticosteroid treatment, mepolizumab (four monthly doses of 750 mg IV) was well tolerated, did not show any severe adverse events and allowed significant steroid tapering in all patients.Citation82 However, clinical markers of disease such as PFTs, fractional exhaled nitric oxide (FeNO) and the Birmingham Vasculitis Activity Score (BVAS) did not significantly change during treatment. After mepolizumab discontinuation, EGPA manifestations recurred.

Positive clinical results were found in another small uncontrolled study performed in refractory or relapsing EGPA despite treatment with immunosuppressants and glucocorticoids at a dose ≥12.5 mg per day.Citation43 Mepolizumab (administered in nine monthly doses of 750 mg IV) led to disease remission in eight out of ten patients. In this study, remission was defined as a negative BVAS and the need for a maintenance steroid dose of ≤7.5 mg per day. As in the aforementioned study, after mepolizumab discontinuation and switching to methotrexate maintenance therapy, seven relapses occurred.Citation43 These results led the authors to consider the use of mepolizumab not only during the induction of disease remission but also as prolonged maintenance therapy to avoid relapses.

After these preliminary promising results, a double-blind randomized controlled trial (RCT) was conducted in 2017 to evaluate the efficacy and safety of mepolizumab in refractory or relapsing EGPA.Citation81 In this study, 136 patients were randomly assigned to receive mepolizumab vs placebo, in addition to standard of care, over a period of 52 weeks and then followed up for 8 weeks. Differently from the previously cited studies, mepolizumab was administered SC every 4 weeks at a dose of 300 mg (three times the approved dose for severe eosinophilic asthma). The decision to use this dose was based on prior trials on mepolizumab in severe eosinophilic asthma.Citation66 Pavord et al tested different mepolizumab IV doses and observed that 250 mg had similar efficacy to 750 mg, but greater efficacy than 75 mg in reducing plasma eosinophils in severe asthmatic patients.Citation66 Based on this observation and drug absolute bioavailability, Wechsler et al found that mepolizumab 300 mg SC was equivalent to 250 mg IV and thus chose this dose for their study on EGPA.Citation81 Primary endpoints of this study were the accrued weeks of remission and the proportion of patients who had remission at both weeks 36 and 48. Remission was defined as a BVAS of 0 and a daily dose of systemic steroid of ≤4 mg over the 52-week period. The trial met both of the primary efficacy endpoints: 28% of patients treated with mepolizumab achieved remission for an accrued time of at least 24 weeks, compared to 3% of those in the placebo group (P<0.001), and 32% of patients in the mepolizumab group had remission at both weeks 36 and 48, compared to 3% in the placebo group (P<0.001). Almost half of the patients (47%) in the treatment group did not achieve remission, compared to 81% of those in the placebo group. This first RCT showed the effectiveness of mepolizumab in maintaining remission until the end of the study and in prolonging the time to first major relapse compared to placebo, with a safety profile similar to that seen in other studies. The most frequent adverse events reported in the study by Wechsler et al were headache (32% in mepolizumab vs 18% in the placebo group), arthralgia (22% vs 18% in the mepolizumab and placebo groups, respectively), nasopharingitis and upper respiratory tract infections.Citation81 Therefore, mepolizumab can be considered as an add-on therapy with steroid-sparing effect in cases of relapsing or refractory EGPA. In the USA, these results paved the way in 2017 to the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approval of mepolizumab in adult patients affected by EGPA, at the dose of 300 mg administered by SC injection every 4 weeks. An observational prospective study has also been planned to collect real-life information about the safety and effectiveness of long-term mepolizumab (ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: NCT03557060). Time to EGPA remission and recurrences will be evaluated over a 2-year period. Furthermore, a long-term access program to open-label mepolizumab for patients who participated in the previous RCT and who required a dose of prednisone greater than 5 mg per day is ongoing (ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: NCT03298061).

The results presented by Wechsler et alCitation81 give rise to a series of considerations. Differently from the two pilot studies previously cited,Citation43,Citation82 in which remission was achieved in the great majority of patients, almost half of the patients had a relapse during the study period, indicating that non-Th-2-and non-eosinophil-driven pathways are probably involved in the relapses of the disease. As explained in an earlier section (EGPA pathogenesis: what do we know?), EGPA is a complex disease and mepolizumab may have a role in only a limited number of pathogenic pathways. In this scenario, an attempt is being made to identify the disease phenotypes that are more likely to respond to mepolizumab. Wechsler et al tried to evaluate the role of mepolizumab in different subgroups of patients and found that its efficacy was greater in patients with an absolute eosinophil count greater than 150 cells/mm3 at baseline, while patients with a lower value of eosinophils did not receive a significant benefit from treatment.Citation81 This finding may also partly explain the higher remission rate in the pilot study by Moosig et al.Citation43 Patients in the pilot study had a mean absolute eosinophil count of 537 cells/mm3 compared with a mean absolute eosinophil count in the RCT of 170 cells/mm3. Wechsler et al also tried to divide the study population according to ANCA positivity; however, only a minority of patients (10%) were ANCA positive at baseline, which did not allow them to perform subanalysis on this variable. As underlined by Roufosse, the small sample size also precluded the analysis of mepolizumab efficacy according to the different subtypes of EGPA disease (vasculitic phase characterized by ANCA positivity, alveolar hemorrhage and palpable purpura vs eosinophilic phase characterized by asthma, marked blood eosinophilia, pulmonary infiltrates and sinonasal abnormalities).Citation85 Future studies aimed at finding biomarkers that allow identification of patients in whom mepolizumab can play a role as add-on therapy may lead to a more precise and personalized approach to the treatment of the disease.

Furthermore, even when considering disease remission, the definitions used were different among studies, with the study by Wechsler et alCitation81 having a more restrictive definition and Moosig et alCitation43 a more permissive one, which may have influenced the relapse rates.

After approval by the FDA of the 300 mg dose for EGPA, Thompson et al presented, in a conference abstract in 2018, the preliminary results of a study with lower dose mepolizumab (100 mg per day every 4 weeks, as approved for severe eosinophilic asthma) in a cohort of patients with chronic relapsing EGPA.Citation86 Six patients in chronic steroid therapy with an average dose prednisolone of 9 mg per day were treated with mepolizumab administered in four SC injections of 100 mg (1 injection every month for 4 months). All patients clinically improved after treatment, allowing weaning from steroid after 4–9 months. The most appropriate dose and administration route of mepolizumab are still the subject of debate: both of the pilot studies previously cited used mepolizumab 750 mg monthly IV infusion,Citation43,Citation82 compared with 300 mg monthly SC administration in the RCT.Citation81 These different doses and routes of administration may also contribute to the different remission rates observed; however, more data on long-term efficacy and tolerability are needed.

Another crucial point is the need for immunosuppressive agents for EGPA control after the introduction of mepolizumab. Currently, there are few indications in regard to the concomitant use of immunosuppressors with mepolizumab. The RCTs available on the use of mepolizumab and other monoclonal antibodies against IL-5, such as reslizumab and benralizumab, for the treatment of EGPA allow the continuation of immunosuppressors during the study (ClinicalTrials.gov identifiers: NCT02947945; NCT03010436).Citation81 Among the most commonly used immunosuppressive drugs for EGPA, azathioprine, mycophenolate mofetil and cyclophosphamide must be acknowledged. Azathioprine is a purine anti-metabolite that acts on actively proliferating cells, particularly antigen-stimulated lymphocytes, causing proliferation block. Mycophenolate mofetil is a reversible inhibitor of inosine monophosphate dehydrogenase and acts on purine synthesis. Its main target is actively proliferating antigen-stimulated lymphocytes. Cyclophosphamide is a cytotoxic drug that causes DNA alkylation at guanine level, causing apoptosis of lymphocytes by breaking the DNA helices. Therefore, immunosuppressive agents and mepolizumab act on different targets and, considering the complexity of EGPA pathogenesis and the number of pathways involved, this seems to suggest a potential adjuvant role of the two therapies rather than a substitutive role of one or the other.

In consideration of the evidence available, the opinion of the authors of this review is to continue immunosuppressive therapy at the time of initiation of mepolizumab or other inhibitors of the immunologic axis of IL-5. During follow-up, the adjustment or reduction of both immunosuppressive and steroid therapy will be conducted according to clinical response to the new agent.

Given this current evidence, the potential place in therapy for mepolizumab in EGPA is as add-on treatment in cases of refractory or relapsing disease, despite optimization of first line treatment (steroids and/or immunosuppressors). Its role as a steroid-sparing agent has also been explored, with good preliminary results. However, the most effective and tolerated dose in EGPA still needs to be determined, and studies are ongoing.

Conclusion and future perspectives

Mepolizumab has been effectively used in patients with severe refractory eosinophilic asthma in recent years.Citation83 Considering the similarities between EGPA and severe eosinophilic asthma pathogenesis, mepolizumab has been introduced as an add-on therapeutic agent in refractory or relapsing EGPA, with promising preliminary results. However, it is still not clear whether the efficacy of mepolizumab in the treatment of EGPA is due mainly to its ability to control asthma symptoms or whether it also plays a role in systemic vasculitis manifestations.Citation84 As described in the “EGPA pathogenesis: what do we know?” section, tissue damage in EGPA is not completely due to eosinophilic inflammation, and the activity of mepolizumab on other factors is probably minimal.

Furthermore, the paucity of high-quality data and the lack of longitudinal information make our knowledge on the best dose to use and the duration of therapy uncertain. Future studies on larger multinational populations with prolonged follow-up are needed to shed light on these unanswered questions.

Author contributions

All authors were involved in the study concept and design, acquisition and interpretation of data, manuscript writing, critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content, gave final approval of the version to be published, and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- VarricchiGBagnascoDFerrandoMPuggioniFPassalacquaGCanonicaGWMepolizumab in the management of severe eosinophilic asthma in adults: current evidence and practical experienceTher Adv Respir Dis2017111404527856823

- WechslerMEAkuthotaPKhouryPNovel Treatments for Airway DiseaseN Engl J Med20173776597598

- ChurgJStraussLAllergic granulomatosis, allergic angiitis, and peri-arteritis nodosaAm J Pathol195127227730114819261

- LanhamJGElkonKBPuseyCDHughesGRSystemic vasculitis with asthma and eosinophilia: a clinical approach to the Churg-Strauss syndromeMedicine198463265816366453

- MasiATHunderGGLieJTThe American College of Rheumatology 1990 criteria for the classification of Churg-Strauss syndrome (allergic granulomatosis and angiitis)Arthritis Rheum1990338109411002202307

- WattsRLaneSHanslikTDevelopment and validation of a consensus methodology for the classification of the ANCA-associated vasculitides and polyarteritis nodosa for epidemiological studiesAnn Rheum Dis200766222222716901958

- SinicoRABotteroPChurg-Strauss angiitisBest Pract Res Clin Rheumatol200923335536619508943

- JennetteJCFalkRJAndrassyKNomenclature of systemic vasculitides. Proposal of an international consensus conferenceArthritis Rheum19943721871928129773

- JennetteJCFalkRJBaconPA2012 Revised International Chapel Hill Consensus Conference Nomenclature of VasculitidesArthritis & Rheumatism201365111123045170

- ComarmondCPagnouxCKhellafMEosinophilic granulomatosis with polyangiitis (Churg-Strauss): clinical characteristics and long-term followup of the 383 patients enrolled in the French Vasculitis Study Group cohortArthritis Rheum201365127028123044708

- SinicoRAdi TomaLMaggioreUPrevalence and clinical significance of antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies in Churg-Strauss syndromeArthritis Rheum20055292926293516142760

- TsukadairaAOkuboYKitanoKEosinophil active cytokines and surface analysis of eosinophils in Churg-Strauss syndromeAllergy Asthma Proc1999201394410076708

- KouroTTakatsuKIL-5- and eosinophil-mediated inflammation: from discovery to therapyInt Immunol200921121303130919819937

- Sablé-FourtassouRCohenPMahrAAntineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies and the Churg-Strauss syndromeAnn Intern Med2005143963263816263885

- AbrilAChurg-strauss syndrome: an updateCurr Rheumatol Rep201113648949521863326

- SimonHURothenbergMEBochnerBSRefining the definition of hypereosinophilic syndromeJ Allergy Clin Immunol20101261454920639008

- ValentPKlionADHornyHPContemporary consensus proposal on criteria and classification of eosinophilic disorders and related syndromesJ Allergy Clin Immunol2012130360761222460074

- GuillevinLCohenPGayraudMLhoteFJarrousseBCasassusPChurg-Strauss syndrome. Clinical study and long-term follow-up of 96 patientsMedicine199978126379990352

- VaglioAMartoranaDMaggioreUHLA-DRB4 as a genetic risk factor for Churg-Strauss syndromeArthritis Rheum20075693159316617763415

- WieczorekSHellmichBArningLFunctionally relevant variations of the interleukin-10 gene associated with antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody-negative Churg-Strauss syndrome, but not with Wegener’s granulomatosisArthritis Rheum20085861839184818512809

- WieczorekSHellmichBGrossWLEpplenJTAssociations of Churg-Strauss syndrome with the HLA-DRB1 locus, and relationship to the genetics of antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody-associated vasculitides: comment on the article by Vaglio et alArthritis Rheum200858132933018163478

- SchmittWHCsernokEKobayashiSKlinkenborgAReinhold-KellerEGrossWLChurg-Strauss syndrome: serum markers of lymphocyte activation and endothelial damageArthritis Rheum19984134454529506572

- GuidaGVallarioAStellaSClonal CD8+ TCR-Vbeta expanded populations with effector memory phenotype in Churg Strauss syndromeClin Immunol200812819410218502180

- GuillevinLAmourouxJArbeilleBBouraRChurg-Strauss angiitis. Arguments favoring the responsibility of inhaled antigensChest19911005147214731935321

- DietzAHübnerCAndrassyKMacrolide antibiotic-induced vasculitis (Churg-Strauss syndrome)Laryngorhinootologie19987721111149555706

- ImaiHNakamotoYHirokawaMAkihamaTMiuraABCarbamazepine-induced granulomatous necrotizing angiitis with acute renal failureNephron19895134054082918954

- MathurSDooleyJScheuerPJQuinine induced granulomatous hepatitis and vasculitisBMJ19903006724613

- GuillevinLGuittardTBletryOGodeauPRosenthalPSystemic necrotizing angiitis with asthma: causes and precipitating factors in 43 casesLung198716531651723108593

- BibbySHealyBSteeleRKumareswaranKNelsonHBeasleyRAssociation between leukotriene receptor antagonist therapy and Churg-Strauss syndrome: an analysis of the FDA AERS databaseThorax2010652132138

- Gómez-PuertaJAGedmintasLCostenbaderKHThe association between silica exposure and development of ANCA-associated vasculitis: systematic review and meta-analysisAutoimmun Rev201312121129113523820041

- KostianovskyACharlesPAlvesJFImmunogenicity and safety of seasonal and 2009 pandemic A/H1N1 influenza vaccines for patients with autoimmune diseases: a prospective, monocentre trial on 199 patientsClin Exp Rheumatol2012301 Suppl 70S83S8922640652

- WechslerMEWongDAMillerMKLawrence-MiyasakiLChurgstrauss syndrome in patients treated with omalizumabChest2009136250751819411292

- GreenRLVayonisAGChurg-Strauss syndrome after zafirlukast in two patients not receiving systemic steroid treatmentThe Lancet19993539154725726

- WechslerMEFinnDGunawardenaDChurg-Strauss syndrome in patients receiving montelukast as treatment for asthmaChest2000117370871310712995

- PuéchalXRivereauPVinchonFChurg-Strauss syndrome associated with omalizumabEur J Intern Med200819536436618549941

- HauserTMahrAMetzlerCThe leucotriene receptor antagonist montelukast and the risk of Churg-Strauss syndrome: a case-crossover studyThorax200863867768218276721

- KhouryPGraysonPCKlionADEosinophils in vasculitis: characteristics and roles in pathogenesisNat Rev Rheumatol201410847448325003763

- SaitoHTsurikisawaNTsuburaiTOshikataCAkiyamaKThe proportion of regulatory T cells in the peripheral blood reflects the relapse or remission status of patients with Churg-Strauss syndromeInt Arch Allergy Immunol2011155Suppl 1465221646795

- KieneMCsernokEMüllerAMetzlerCTrabandtAGrossWLElevated interleukin-4 and interleukin-13 production by T cell lines from patients with Churg-Strauss syndromeArthritis Rheum200144246947311229479

- DunoguéBPagnouxCGuillevinLChurg-strauss syndrome: clinical symptoms, complementary investigations, prognosis and outcome, and treatmentSemin Respir Crit Care Med201132329830921674415

- JakielaBSanakMSzczeklikWBoth Th2 and Th17 responses are involved in the pathogenesis of Churg-Strauss syndromeClin Exp Rheumatol2011291 Suppl 64S23S34

- JakielaBSzczeklikWPluteckaHIncreased production of IL-5 and dominant Th2-type response in airways of Churg-Strauss syndrome patientsRheumatology201251101887189322772323

- MoosigFGrossWLHerrmannKBremerJPHellmichBTargeting interleukin-5 in refractory and relapsing Churg-Strauss syndromeAnn Intern Med2011155534134321893636

- TerrierBBiècheIMaisonobeTInterleukin-25: a cytokine linking eosinophils and adaptive immunity in Churg-Strauss syndromeBlood2010116224523453120729468

- VaglioAMoosigFZwerinaJChurg-Strauss syndrome: update on pathophysiology and treatmentCurr Opin Rheumatol2012241243022089097

- MahrAGuillevinLPoissonnetMAyméSPrevalences of polyarteritis nodosa, microscopic polyangiitis, Wegener’s granulomatosis, and Churg-Strauss syndrome in a French urban multiethnic population in 2000: A capture-recapture estimateArthritis Care Res20045119299

- WattsRALaneSEBenthamGScottDGEpidemiology of systemic vasculitis: a ten-year study in the United KingdomArthritis Rheum200043241441910693883

- ZwerinaJBachCMartoranaDEotaxin-3 in Churg-Strauss syndrome: a clinical and immunogenetic studyRheumatology201150101823182721266446

- PolzerKKaronitschTNeumannTEotaxin-3 is involved in Churg-Strauss syndrome – a serum marker closely correlating with disease activityRheumatology200847680480818397958

- BaldiniCTalaricoRdella RossaABombardieriSClinical manifestations and treatment of Churg-Strauss syndromeRheum Dis Clin North Am201036352754320688248

- VaglioAStrehlJDMangerBIgG4 immune response in Churg-Strauss syndromeAnn Rheum Dis201271339039322121132

- Ramentol-SintasMMartínez-ValleFSolans-LaquéRChurg-Strauss Syndrome: an evolving paradigmAutoimmun Rev201212223524022796280

- ChurgARecent advances in the diagnosis of Churg-Strauss syndromeMod Pathol200114121284129311743052

- TsurikisawaNSaitoHTsuburaiTDifferences in regulatory T cells between Churg-Strauss syndrome and chronic eosinophilic pneumonia with asthmaJ Allergy Clin Immunol2008122361061618586318

- LepseNAbdulahadWHKallenbergCGHeeringaPImmune regulatory mechanisms in ANCA-associated vasculitidesAutoimmun Rev2011112778321856453

- FreeMEBunchDOMcgregorJAPatients with antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody-associated vasculitis have defective Treg cell function exacerbated by the presence of a suppression-resistant effector cell populationArthritis Rheum20136571922193323553415

- VaglioACasazzaIGrasselliCCorradiDSinicoRABuzioCChurg-Strauss syndromeKidney Int20097691006101119516244

- FalkRJTerrellRSCharlesLAJennetteJCAnti-neutrophil cytoplasmic autoantibodies induce neutrophils to degranulate and produce oxygen radicals in vitroProc Natl Acad Sci U S A19908711411541192161532

- XiaoHHeeringaPHuPAntineutrophil cytoplasmic autoantibodies specific for myeloperoxidase cause glomerulonephritis and vasculitis in miceJ Clin Invest2002110795596312370273

- Flood-PagePTMenzies-GowANKayABRobinsonDSEosinophil’s role remains uncertain as anti-interleukin-5 only partially depletes numbers in asthmatic airwayAm J Respir Crit Care Med2003167219920412406833

- Flood-PagePSwensonCFaifermanIA study to evaluate safety and efficacy of mepolizumab in patients with moderate persistent asthmaAm J Respir Crit Care Med2007176111062107117872493

- Menzies-GowAFlood-PagePSehmiRAnti-IL-5 (mepolizumab) therapy induces bone marrow eosinophil maturational arrest and decreases eosinophil progenitors in the bronchial mucosa of atopic asthmaticsJ Allergy Clin Immunol2003111471471912704348

- HaldarPBrightlingCEHargadonBMepolizumab and exacerbations of refractory eosinophilic asthmaN Engl J Med20093601097398419264686

- ChuppGLBradfordESAlbersFCEfficacy of mepolizumab add-on therapy on health-related quality of life and markers of asthma control in severe eosinophilic asthma (MUSCA): a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, parallel-group, multicentre, phase 3b trialLancet Respir Med20175539040028395936

- NairPPizzichiniMMKjarsgaardMMepolizumab for prednisone-dependent asthma with sputum eosinophiliaN Engl J Med20093601098599319264687

- PavordIDKornSHowarthPMepolizumab for severe eosinophilic asthma (DREAM): a multicentre, double-blind, placebo-controlled trialLancet2012380984265165922901886

- OrtegaHGLiuMCPavordIDMepolizumab treatment in patients with severe eosinophilic asthmaN Engl J Med Overseas Ed20143711311981207

- BelEHWenzelSEThompsonPJOral glucocorticoid-sparing effect of mepolizumab in eosinophilic asthmaN Engl J Med2014371131189119725199060

- SpadaroGPecoraroAde RenzoAdella PepaRGenoveseAIntravenous versus subcutaneous immunoglobulin replacement in secondary hypogammaglobulinemiaClin Immunol2016166–167103104

- KallurLGonzalez-EstradaAEidelmanFDimovVPharmacokinetic drug evaluation of mepolizumab for the treatment of severe asthma associated with persistent eosinophilic inflammation in adultsExpert Opin Drug Metab Toxicol201713121275128029157020

- DasguptaAKjarsgaardMCapaldiDA pilot randomised clinical trial of mepolizumab in COPD with eosinophilic bronchitisEur Respir J2017493160248628298405

- PavordIDChanezPCrinerGJMepolizumab for eosinophilic chronic obstructive pulmonary diseaseN Engl J Med Overseas Ed20173771716131629

- SteinMLVillanuevaJMBuckmeierBKAnti–IL-5 (mepolizumab) therapy reduces eosinophil activation ex vivo and increases IL-5 and IL-5 receptor levelsJ Allergy Clin Immunol200812161473148318410960

- SteinMLCollinsMHVillanuevaJMAnti-IL-5 (mepolizumab) therapy for eosinophilic esophagitisJ Allergy Clin Immunol200611861312131917157662

- PlötzS-GSimonH-UDarsowUUse of an Anti–Interleukin-5 Antibody in the Hypereosinophilic Syndrome with Eosinophilic DermatitisN Engl J Med Overseas Ed20033492423342339

- RothenbergMEKlionADRoufosseFETreatment of Patients with the Hypereosinophilic Syndrome with MepolizumabN Engl J Med Overseas Ed20083581212151228

- KuangFLFayMPWareJLong-term clinical outcomes of high-dose mepolizumab treatment for hypereosinophilic syndromeJ Allergy Clin Immunol Pract2018651518152729751154

- RoufosseFEKahnJ-EGleichGJLong-term safety of mepolizumab for the treatment of hypereosinophilic syndromesJ Allergy Clin Immunol20131312461e14675e123040887

- KahnJ-EGrandpeix-GuyodoCMarrounISustained response to mepolizumab in refractory Churg-Strauss syndromeJ Allergy Clin Immunol2010125126727020109753

- HerrmannKGrossWLMoosigFExtended follow-up after stopping mepolizumab in relapsing/refractory Churg-Strauss syndromeClin Exp Rheumatol2012301 Suppl 70S62S65

- WechslerMEAkuthotaPJayneDMepolizumab or placebo for eosinophilic granulomatosis with polyangiitisN Engl J Med Overseas Ed20173762019211932

- KimSMarigowdaGOrenEIsraelEWechslerMEMepolizumab as a steroid-sparing treatment option in patients with Churg-Strauss syndromeJ Allergy Clin Immunol201012561336134320513524

- FarneHAWilsonAPowellCBaxLMilanSJAnti-IL5 therapies for asthmaCochrane Airways GroupCochrane Database Syst Rev [cited 2018 July 29]. Available from: http://doi.wiley.com/10.1002/14651858.CD010834.pub3Accessed date: September 21, 2017

- GuillevinLVasculitis: Mepolizumab for eosinophilic granulomatosis with polyangiitisNat Rev Rheumatol201713951851928769112

- RoufosseFTargeting the interleukin-5 pathway for treatment of eosinophilic conditions other than asthmaFront Med2018549

- ThompsonGVasilevskiNRyanMBalticSThompsonPLow-dose mepolizumab effectively treats chronic relapsing eosinophilic granulomatosis with polyangiitisRespirologySupplement: The Australia & New Zealand Society of Respiratory Science and The Thoracic Society of Australia and New Zealand (ANZSRS/TSANZ) Annual Scientific MeetingAdelaide, Australia23–27 March 2018201823Suppl 1178