Abstract

Purpose

To analyze and compare the signals of bleeding from the use of direct-acting oral anticoagulants (DOACs) in the US Food and Drug Administration Adverse Event Reporting System (FAERS) database over 5 years.

Methods

Reports of bleeding and of events with related terms submitted to the FAERS between October 2010 and September 2015 were retrieved and then analyzed using the reporting odds ratio (ROR). The signals of bleeding associated with DOAC use were compared with the signals of bleeding associated with warfarin use utilizing the FAERS databases.

Results

A total of 1,518 reports linked dabigatran to bleeding, accounting for 2.7% of all dabigatran-related reports, whereas 93 reports linked rivaroxaban to bleeding, which accounted for 4.4% of all rivaroxaban-related reports. The concurrent proportion of bleeding-related reports for warfarin was 3.6%, with a total of 654 reports. The association of bleeding and of related terms with the use of all three medications was significant, albeit with different degrees of association. The ROR was 12.30 (95% confidence interval [CI] 11.65–12.97) for dabigatran, 15.61 (95% CI 14.42–16.90) for warfarin, and 18.86 (95% CI 15.31–23.23) for rivaroxaban.

Conclusions

The signals of bleeding varied among the DOACs, and the bleeding signal was higher for rivaroxaban and lower for dabigatran compared to that for warfarin.

Introduction

Oral anticoagulants are widely prescribed for patients with venous thromboembolism. Specific scoring systems are useful for determining who should use oral anticoagulants for diseases such as atrial fibrillation. The CHADS2 scoring system is widely used to stratify the risk of thromboembolism in atrial fibrillation patients. Patients at low risk (CHADS2 score = 0) should not be treated with oral anticoagulants, whereas patients at higher risk (CHADS2 score ≥ 2) should be treated. An updated version of CHADS2 is the CHA2 DS2–VASc score, which is used by the European Society of Cardiology and the American College of Cardiology. Evidence indicates that patients with atrial fibrillation at moderate to high thromboembolic risk (CHA2 DS2–VASc ≥ 2) should be treated with oral anticoagulants. Additionally, patients with CHA2 DS2–VASc scores of 1 for men or 2 or above for women should be considered for anticoagulant therapy to prevent stroke.Citation1–Citation4 Warfarin was considered the gold standard anticoagulant therapy to prevent stroke and to prevent and treat deep venous thrombosis and pulmonary embolism for many years, albeit the only option available at the time. Warfarin was also used to prevent and treat thromboembolic complications in patients with cardiac valve replacement and/or atrial fibrillation and to reduce the risk of death, stroke or systemic embolization after myocardial infarction and recurrent myocardial infarction. It is also used for patients with cerebral transient ischemic attack.Citation5–Citation8 However, warfarin is a narrow therapeutic index drug, which encumbers the maintenance of patients at the required therapeutic level. A study found that approximately 50% of patients were out of the normal therapeutic range. Moreover, inter-individual variability in response to warfarin therapy exists, which causes warfarin dose variance among patients. Therefore, patients using warfarin require close monitoring, particularly at the beginning of treatment, because of the risk of bleeding and potential drug interactions.Citation9–Citation12

Direct-acting oral anticoagulants (DOACs) were introduced to the market in the new century. Two classes of DOACs are currently available: oral direct thrombin inhibitors (DTIs; eg, dabigatran) and oral direct factor Xa inhibitors (eg, rivaroxaban, apixaban, edoxaban, and betrixaban). Dabigatran was approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) in October 2010 for the prevention of stroke in patients with non-valvular atrial fibrillation.Citation13 Rivaroxaban and dabigatran are prescribed as alternatives to warfarin to prevent stroke in patients with atrial fibrillation. Furthermore, as per the CHEST (2016) guidelines, rivaroxaban and dabigatran may be used preferentially over warfarin as an anticoagulant therapy for venous thromboembolism.Citation14

Clinical trials demonstrated that dabigatran was comparable to warfarin regarding efficacy and safety.Citation15–Citation17 Some of the advantages of dabigatran over warfarin include the lack of a need for routine blood monitoring, a standard dosing regimen and fewer drug interactions. Additionally, because of its short half-life (12–17 hours), dabigatran use may not require bridging therapy before surgery. The protein binding of dabigatran is approximately 35% and its volume of distribution is 50–70 L.Citation18

Rivaroxaban was approved by the US FDA in mid-2011 as prophylaxis for deep venous thrombosis and, later in the same year, for the prevention of stroke in patients with non-valvular atrial fibrillation. Rivaroxaban has high plasma protein binding (92%–95%), a volume of distribution of 50 L and a half-life of 5–9 hours.Citation19 For patients with atrial fibrillation, rivaroxaban was non-inferior to warfarin for the prevention of stroke and systemic embolism.Citation20 However, fatal bleeding occurred less frequently in the rivaroxaban group. Notably, the normal rivaroxaban dosage for atrial fibrillation is 20 mg once daily and, for patients with a creatinine clearance 15–50 mL/min, 15 mg once daily.Citation19,Citation21

A systematic review reported no differences in the risks of non-hemorrhagic stroke and systemic embolic events between DOACs (rivaroxaban, dabigatran and apixaban) and warfarin.Citation22 However, the risk of intracranial bleeding with DOAC use was lower than that with warfarin use (relative risk [RR] = 0.46; 95% CI = 0.33–0.65). shows the landmark clinical trials for the DOACs included in the study.

Table 1 Safety and efficacy endpoints for landmark clinical trials for studied drugs

Adverse drug reactions (ADRs) cannot be easily detected in studies conducted before a new drug reaches the market for use in patients. However, after the drug is marketed, new spontaneous reports of ADRs are received by health authorities as a greater number of patients are prescribed the drug for longer periods of use. Observations from real-world data indicated increased cases of major bleeding in older patients, extremely obese patients and patients with impaired renal function who were using dabigatran.Citation23 Real-world data provide confirmative information on bleeding risks to help clinicians weigh the risks and benefits of these agents.

The FDA established the FDA Adverse Event Reporting System (FAERS) database to support post-marketing surveillance programs. The FAERS is a computerized database of more than nine million adverse event reports, including all reports from 1969 to the present time. Epidemiologists and other scientific personnel may access the reports submitted to the FAERS, and the FDA may depend on these reports to take action regarding medication safety concerns.Citation24

Therefore, the aim of this study was to evaluate the associations between the use of warfarin (Coumadin®; Bristol-Myers Squibb, New York, NY, USA), dabigatran (Pradaxa®; Boehringer Ingelheim, Ingelheim am Rhein, Germany) and rivaroxaban (Xarelto®; Janssen Pharmaceutica NV, Beerse, Belgium) and the signals of bleeding using a case/non-case method. Other DOACs (apixaban and edoxaban) were not included in this study because they were approved during the study period.

Methods

Data source

Reports of bleeding events submitted to the FAERS database over 5 years (2010–2015) were retrieved and then analyzed using the reporting odds ratio (ROR). The FAERS contains adverse event and medication error reports submitted by healthcare professionals and consumers. The FAERS datasets may be freely accessed using the FDA website (https://open.fda.gov/data/faers/).Citation25 The FAERS accepts reports from all regions of the country and from international manufacturers. Adverse event reporting by pharmaceutical companies is mandatory, whereas reporting by healthcare professionals is voluntary. For inclusion in the database, reports must include an identifiable patient, an identifiable reporter, the suspected drug and the adverse event encountered.

Data collection

The FDA publishes FAERS files every quarter (ie, four comprehensive files published each year). Each quarterly file consists of seven sub-files, which include the following: a demographic file that includes patient demographic and administrative data; a drug file that includes drugs that the patient has taken, including suspected and any concomitant drugs; a reaction file that includes the medical dictionary for regulatory activities terms coded for the adverse event (the FDA, similar to other authorities, uses these preferred terms as the main terms for adverse events); an outcome file that includes patient outcomes for the event; a source file that contains the sources of reports; a file of therapy dates that includes drug therapy start dates and end dates for the reported drugs; and a file with indications for use that includes the medical dictionary for regulatory activities coding for indications for use (diagnoses) for the reported drugs.Citation26–Citation28

All these files include one unique report ID, which is referred to as the primary ID in files from 2013 and as the individual safety report (ISR) before 2013. These unique IDs were used to merge all these files both within and between years.Citation27

Reports of each bleeding event in the present analysis were submitted to the FAERS between October 2010 and September 2015, and the medications of interest that were considered a potential cause of bleeding were retrieved. The main medications of interest were warfarin, dabigatran and rivaroxaban. Searches were performed using both the generic and brand names of each medication. Additionally, searches were performed for subsets of medication-related terms (as a part of the word), and findings were reviewed case by case. Drug indications were also assessed to ensure that no discrepancies existed between the drug and its indication. Moreover, we included only the drug suspected to be the primary agent.

The outcome of interest was bleeding and was searched for using the terms “bleed,” “bleeding,” “hemorrhage” and “haemorrhage” in the preferred terms field in the FAERS database. Other data on demographic information and reporter type were also collected. Duplicate reports and contradictory data were excluded by reviewing the unique ID (primary ID or ISR) and the case number (CASE or CASEID).

Statistical analysis

The case/non-case methodology was used to evaluate the association between bleeding and the use of the drugs of interest. Cases were defined as reports of the outcome of interest, ie, bleeding, and were identified by searching for related terms such as “bleed,” “bleeding,” “hemorrhage” and “haemorrhage” or subsets of these terms in the preferred terms field. Cases were extracted based on the preferred terms for any given drug. The temporal relationship between the start and event dates (ie, start dates preceding event dates) was assessed because it is an important factor in case identification. A case by case review was conducted by the research team to ascertain the time points described above.

Non-cases were defined as all non-bleeding-related reports for the same drug. Reports indicating a drug of interest as the primary suspected drug were included in the analyses. The ROR was used to evaluate the association between the drugs of interest and bleeding. The ROR estimates the odds of bleeding among those exposed to the drugs of interest divided by the odds of bleeding among those not exposed to the drugs of interest. The case/non-case report ratio for each group was compared to that of the other medications. As mentioned above, this method is used in most of the studies using spontaneous ADR reporting databases to calculate ROR, which is obtained by the equation (ad*bc), where a is the number of cases for the studied drug, b is the number of non-cases for the studied drug, c is the number of cases for other drugs in the database, and d is the number of non-cases for other drugs in the database.Citation29 All statistical analyses were conducted using Statistical Analysis Software (SAS 9.3) (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA).

Confidentiality

The study investigators had no access to the personal patient and reporter data during the review and analysis of reports from the FAERS database. This study was approved by the medication safety research chair at King Saud University.

Results

In total, 18,231 reports were on warfarin, 56,039 reports were on dabigatran, and 2,095 reports were on rivaroxaban as the primary suspected product in the period between October 2010 and September 2015. A total of 1,518 reports linked dabigatran to bleeding, accounting for 2.7% of all dabigatran-related reports, whereas 93 reports linked rivaroxaban to bleeding, which accounted for 4.4% of all rivaroxaban-related reports. Concurrently, 654 reports linked bleeding to warfarin, which accounted for 3.6% of all warfarin-related reports. For all the drugs, most of the reports were from the US and involved male patients. However, reports of dabigatran-associated bleeding occurred at similar rates in males and females ().

Table 2 Demographic distribution of reports

The ROR was significant for the risk of bleeding with the use of all three medications, albeit with varying degrees of association. The ROR was lowest for dabigatran (12.30 [95% CI 11.65–12.97]) among the investigated medications, whereas the ROR was highest for rivaroxaban (18.86 [95% CI 15.31–23.23]) ().

Table 3 The ROR and associated 95% CIs for bleeding following dabigatran, rivaroxaban or warfarin use

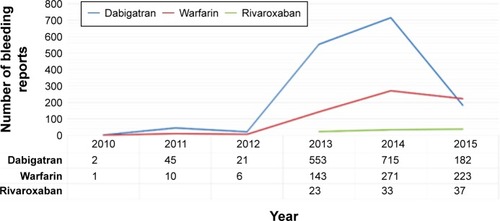

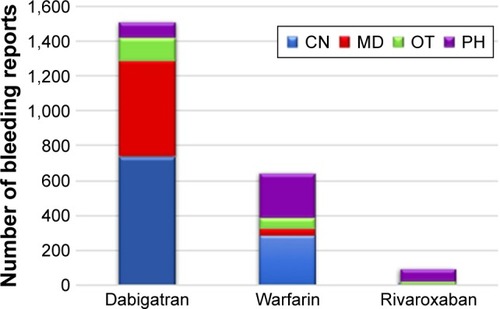

The highest number of reported cases for dabigatran was for the period between 2013 and 2014, whereas for warfarin and rivaroxaban, the highest number of reported cases was for the period between 2014 and 2015 (). Most of the bleeding reports associated with dabigatran and warfarin were sent by consumers, whereas pharmacists were the most frequent reporting party for rivaroxaban-related bleeding cases ().

Discussion

Post-marketing surveillance is conducted after a new drug application is approved by the FDA to monitor the safety of medications and to identify medication-associated risks. The potential consumers after the release of a drug to market differ from the homogenous study population of the clinical trial, and thus, more valuable information may be provided from consumers than from data collected in the randomized trial.Citation30

In this study, we demonstrated that, compared to warfarin and dabigatran, rivaroxaban was associated with a higher risk of bleeding. The risk of bleeding among these oral anticoagulant medications was lowest for dabigatran. Several studies reported the association between oral anticoagulants and bleeding and support our finding regarding the high risk associated with rivaroxaban use. A recent systematic review included 17 different studies and reported that rivaroxaban had a significantly higher risk of major bleeding than dabigatran (hazard ratio, 1.38; 95% CI, 1.27–1.49).Citation31 Another meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials found that DOACs were associated with an increased risk of gastrointestinal bleeding, with ORs of 1.58 (95% CI, 1.29–1.93) for dabigatran and 1.48 (95% CI, 1.21–1.82) for rivaroxaban.Citation32 A study conducted in 2016 that included older adult patients (>65 years) with non-valvular atrial fibrillation reported higher rates of intracerebral hemorrhage and gastrointestinal bleeding among patients taking 20 mg of rivaroxaban daily compared with the rates among patients taking 150 mg of dabigatran twice daily.Citation33

In contrast to our study, spontaneous reports to the Australian Therapeutic Goods Administration between June 2009 and May 2014 revealed more reports of hemorrhages associated with dabigatran than those associated with rivaroxaban (504 vs 240).Citation34 Compared to this Australian study, our study revealed three times more reports of bleeding due to dabigatran (504 vs 1,518) and less than half the number of reports of bleeding due to rivaroxaban (93 vs 240).Citation17 The randomized evaluation of long-term anticoagulation therapy reported that the frequency of major gastrointestinal bleeding was significantly higher with dabigatran use than that with warfarin use.Citation35 A limitation of the spontaneous reports submitted to the FAERS is that the reports generally do not contain data regarding the patients’ risk factors, age and renal function or whether the dose complied with the drug manufacturer’s directions.Citation36 Additionally, the availability of more than one anticoagulant agent poses a challenge for healthcare professionals in choosing the appropriate option because information on which patient group is most likely to benefit from a specific drug is not yet available. One study found that patients younger than 65 years had less risk of gastrointestinal bleeding when using DOACs.Citation37 This causes a dilemma because according to an epidemiological study conducted in 2010, 9% of the US population aged 80 years or older has atrial fibrillation.Citation38 Moreover, older adults are less likely to be initiated on dabigatran because the risk of bleeding among adults older than 80 years is high, including at low doses such as 110 mg twice daily.Citation39

All the above-mentioned factors may affect the validity of the submitted reports, which may influence the safety alerts generated by the FDA and the regulatory authorities. Our study found that consumers were most often the reporting party. Spontaneous reporting by consumers is increasing yearly given the importance of involving patients in the reporting process. The US, along with the European Union, has facilitated consumer reporting by establishing the Adverse Medicine Events Line, electronic reporting systems and smartphone applications, such as MedWatcher.Citation40

This study has several strengths, such as the use of a rich, open-access database that includes millions of reports from the US and other countries. Furthermore, these data are not limited to US FDA researchers and may be utilized by any other researchers. However, this study also has several limitations, including (1) under-reporting, (2) over-reporting, (3) missing data and lack of complete information in the report, and (4) the unknown denominator for exposure.Citation41 Additionally, we were unable to assess other DOACs (apixaban and edoxaban) because they were approved during the study period. Despite the limitations of the case/non-case method and the FAERS database, we believe that the data in this study may offer an important reference for defining the safety profile of these medications.

Conclusion

Analysis of the FAERS database suggests that the signals of bleeding vary among DOACs, ie, the bleeding signal was higher for rivaroxaban and lower for dabigatran relative to the bleeding signal for warfarin. However, all these medications have a high risk of bleeding. Healthcare professionals might consider the findings of this study along with those of previous studies in their daily medical practice.

Acknowledgments

The abstract of this study was presented as a poster abstract at the 32nd International Conference on Pharmacoepidemiology & Therapeutic Risk Management, Dublin, Ireland, August 25–28, 2016. This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- KirchhofPBenussiSKotechaD2016 ESC Guidelines for the management of atrial fibrillation developed in collaboration with EACTSEur Heart J201637382893296227567408

- HartRGPearceLAAguilarMIMeta-analysis: antithrombotic therapy to prevent stroke in patients who have nonvalvular atrial fibrillationAnn Intern Med20071461285786717577005

- CooperNJSuttonAJLuGKhuntiKMixed comparison of stroke prevention treatments in individuals with nonrheumatic atrial fibrillationArch Intern Med2006166121269127516801509

- JanuaryCTWannLSAlpertJS2014 AHA/ACC/HRS guideline for the management of patients with atrial fibrillation: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines and the Heart Rhythm SocietyJ Am Coll Cardiol20146421e1e7624685669

- AnsellJHirshJHylekEJacobsonACrowtherMPalaretiGPharmacology and management of the vitamin K antagonists: American College of Chest Physicians Evidence-Based Clinical Practice Guidelines. 8th edChest20081336 Suppl160S198S18574265

- MuellerRLScheidtSHistory of drugs for thrombotic disease. Discovery, development, and directions for the futureCirculation19948914324498281678

- WarfarinDrugs@FDA. Food and Drug Administration [Internet]. Available from: https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2017/009218s118lbl.pdfAccessed February 5, 2018

- WarfarinElectronic Medicines Compendium [Internet]. Available from: https://www.medicines.org.uk/emc/product/2803Accessed Febuary 5, 2018

- AnsellJHirshJPollerLBusseyHJacobsonAHylekEThe pharmacology and management of the vitamin K antagonists: the Seventh ACCP Conference on Antithrombotic and Thrombolytic TherapyChest20041263 Suppl204S233S15383473

- BoulangerLKimJFriedmanMHauchOFosterTMenzinJPatterns of use of antithrombotic therapy and quality of anticoagulation among patients with non-valvular atrial fibrillation in clinical practiceInt J Clin Pract200660325826416494639

- PirmohamedMWarfarin: almost 60 years old and still causing problemsBr J Clin Pharmacol200662550951117061959

- KimmelSEWarfarin therapy: in need of improvement after all these yearsExpert Opin Pharmacother20089567768618345947

- HughesBFirst oral warfarin alternative approved in the USNat Rev Drug Discov201091290390621030985

- KearonCAklEAOrnelasJAntithrombotic therapy for VTE disease: CHEST guideline and expert panel reportChest2016149231535226867832

- WallentinLYusufSEzekowitzMDEfficacy and safety of dabigatran compared with warfarin at different levels of international normalised ratio control for stroke prevention in atrial fibrillation: an analysis of the RE-LY trialLancet2010376974597598320801496

- ConnollySJEzekowitzMDYusufSDabigatran versus warfarin in patients with atrial fibrillationN Engl J Med2009361121139115119717844

- DienerHCConnollySJEzekowitzMDDabigatran compared with warfarin in patients with atrial fibrillation and previous transient ischaemic attack or stroke: a subgroup analysis of the RE-LY trialLancet Neurol20109121157116321059484

- Dabigatran. Drugs@FDAFood and Drug Administration Available from: https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2015/022512s028lbl.pdfAccessed February 5, 2018

- Food and Drug AdministrationDrugs@FDA: FDA Approved Drug Products Available from: https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/scripts/cder/daf/index.cfm?event=overview.process&ApplNo=022406Accessed January 15, 2018

- PatelMRMahaffeyKWGargJRivaroxaban versus warfarin in nonvalvular atrial fibrillationN Engl J Med20113651088389121830957

- Rivaroxaban. Drugs@FDAFood and Drug Administration Available from: https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2011/202439s001lbl.pdfAccessed February 3, 2017

- Gomez-OutesATerleira-FernandezAICalvo-RojasGSuárez-GeaMLVargas-CastrillónEDabigatran, rivaroxaban, or apixaban versus warfarin in patients with nonvalvular atrial fibrillation: a systematic review and meta-analysis of subgroupsThrombosis2013201364072324455237

- PoliDAntonucciETestaSBleeding risk in very old patients on vitamin K antagonist treatment: results of a prospective collaborative study on elderly patients followed by Italian Centres for AnticoagulationCirculation2011124782482921810658

- Food and Drug AdministrationPost-Marketing Surveillance Programs [updated 2014 Aug 19] Available from: https://www.fda.gov/drugs/guidancecomplianceregulatoryinformation/surveillance/ucm090385.htmAccessed January 15, 2018

- Food and Drug Administration Available from: https://open.fda.gov/data/faers/Accessed January 7, 2018

- The FDA Adverse Event Reporting System (FAERS)Food and Drug Administration (FDA) Available from: https://www.fda.gov/DrugsGuidanceComplianceRegulatoryInformation/Surveillance/Adverse-DrugEffects/Accessed December 13, 2017

- OpenFDAThe FDA Adverse Event Reporting System (FAERS)Food and Drug Administration (FDA) Available from: https://open.fda.gov/data/faers/Accessed December 13, 2017

- SakaedaTTamonAKadoyamaKOkunoYData mining of the public version of the FDA Adverse Event Reporting SystemInt J Med Sci201310779680323794943

- BöhmRReporting odds ratio. primer on disproportionality analysis2015 Available from: http://openvigil.sourceforge.net/doc/DPA.pdfAccessed February 2, 2018

- WaningBMontagneMPharmacoepidemiology Principles and Practice Chapter 8: Post-marketing surveillanceNew YorkMcGraw Hill Education2001

- BaiYDengHShantsilaALipGYRivaroxaban versus dabigatran or warfarin in real-world studies of stroke prevention in atrial fibrillation: systematic review and meta-analysisStroke201748497097628213573

- HolsterILValkhoffVEKuipersEJTjwaETNew oral anticoagulants increase risk for gastrointestinal bleeding: a systematic review and meta-analysisGastroenterology20131451105.e15112.e1523470618

- GrahamDJReichmanMEWerneckeMStroke, bleeding, and mortality risks in elderly medicare beneficiaries treated with dabigatran or rivaroxaban for nonvalvular atrial fibrillationJAMA Intern Med2016176111662167127695821

- ChenEYDiugBBellJSSpontaneously reported haemorrhagic adverse events associated with rivaroxaban and dabigatran in AustraliaTher Adv Drug Saf20167141026834958

- BytzerPConnollySJYangSAnalysis of upper gastrointestinal adverse events among patients given dabigatran in the RE-LY trialClin Gastroenterol Hepatol2013113246252e1523103906

- SouthworthMRReichmanMEUngerEFDabigatran and postmarketing reports of bleedingN Engl J Med2013368141272127423484796

- AbrahamNSSinghSAlexanderGCComparative risk of gastrointestinal bleeding with dabigatran, rivaroxaban, and warfarin: population based cohort studyBMJ2015350h185725910928

- ChughSSHavmoellerRNarayananKWorldwide epidemiology of atrial fibrillation: a Global Burden of Disease 2010 StudyCirculation2014129883784724345399

- StaerkLFosbølELGadsbøllKNon-vitamin K antagonist oral anticoagulation usage according to age among patients with atrial fibrillation: Temporal trends 2011–2015 in DenmarkSci Rep201663147727510920

- MedWatcher Available from: https://medwatcher.org/Accessed February 7, 2017

- EdwardsRLindquistMPharmacovigilance: Critique and Ways ForwardNew YorkSpringer2017

- SchulmanSKearonCKakkarAKExtended use of dabigatran, warfarin, or placebo in venous thromboembolismN Engl J Med2013368870971823425163

- ErikssonBIBorrisLCFriedmanRJRivaroxaban versus enoxaparin for thromboprophylaxis after hip arthroplastyN Engl J Med2008358262765277518579811

- ErikssonBIDahlOERosencherNOral dabigatran etexilate versus enoxaparin for venous thromboembolism prevention after total hip arthroplasty: pooled analysis of two phase 3 randomized trialsThromb J2015133626578849

- SchulmanSKearonCKakkarAKDabigatran versus warfarin in the treatment of acute venous thromboembolismN Engl J Med2009361242342235219966341

- ErikssonBIDahlOERosencherNOral dabigatran etexilate vs. subcutaneous enoxaparin for the prevention of venous thromboembolism after total knee replacement: the RE-MODEL randomized trialJ Thromb and Haemost20075112178218517764540

- GinsbergJSDavidsonBLCompPCOral thrombin inhibitor dabigatran etexilate vs North American enoxaparin regimen for prevention of venous thromboembolism after knee arthroplasty surgeryJ Arthroplasty200924119