Abstract

Aims

To review the evidence for efficacy, safety, and cost-effectiveness of levodopa/carbidopa/entacapone (LCE) compared with levodopa/dopa-decarboxyiase inhibitor (DDCI) for Parkinson’s disease (PD).

Methods

PubMed, Embase, the Cochrane Library, and Chinese databases WangFang Data, Chinese Sci-tech Journals Database and China National Knowledge Infrastructure, as well as ClinicalTrials.gov, were searched for randomized controlled trials with “levodopa/carbidopa/entacapone” as keywords. The search period was from inception to August 2017. We conducted meta-analyses to synthesize the evidence quantitatively.

Results

A total of 5,693 records were obtained. We included seven randomized controlled trials and one cost-effectiveness study after the screening process. Compared with levodopa–DDCI, LCE improved patient Unified Parkinson’s Disease Rating Scale (UPDRS) II score (mean difference [MD] −1.17, 95% CI −1.64 to −0.71), UPDRS III score (MD −1.55, 95% CI −2.29 to −0.81), and Schwab and England daily activity rating (MD 2.05, 95% CI 0.85–3.26). There was no statistically significant difference in the risk of serious adverse events (AEs) or discontinuation due to AEs in patients with LCE, and the risk of total AEs was higher in the LCE group (risk ratio [RR] 1.33, 95% CI 1.05–1.70). The incremental cost-effectiveness ratio of LCE was £3,105 per quality-adjusted life-year (QALY) gained in the UK.

Conclusion

LCE can improve PD patients’ motor symptoms and daily living functioning when compared with levodopa/DDCI.

Introduction

Parkinson’s disease (PD) is considered one of the commonest neurodegenerative diseases. Regarding pathophysiology, the primary cause of PD is the degeneration of dopamine-producing neurons in the substantia nigra and the formation of Lewy bodies. PD is usually suspected in patients presenting with bradykinesia, rigidity, tremors, and/or postural instability.Citation1 Furthermore, the risk of PD increases nearly exponentially with age and peaks after 80 years of age.Citation2 Globally, the estimation of incidence of PD is 10–18 per 100,000 person-years,Citation2 which imposes a considerable disease burden on the patient, the family, and society as a whole, due to medication, hospitalization, and productivity loss.

There is currently no definitive cure for PD. Current pharmacological therapy is mainly designed to control the signs and symptoms associated with PD and includes dopamine replacement and dopamine agonists.Citation3,Citation4 Levodopa is the most efficacious treatment of PD, developed in the late 1960s; however, approximately 70% of oral levodopa is metabolized by aromatic amino-acid decarboxylase in the intestinal mucosa and liver.Citation5 A dopa-decarboxylase inhibitor (DDCI), such as carbidopa or benserazide, is then administered with levodopa to increase drastically the half-life and concentration area under the curve of levodopa. Additionally, another peripheral route of levodopa metabolism is via catechol-O-methyltransferase (COMT). Finally, entacapone is a peripheral, reversible COMT inhibitor that increases the half-life of levodopa to make more levodopa sustainable.

A series of clinical trials on PD patients suggested that the addition of entacapone to levodopa/DDCI increased the “on” time (when patients experience benefit from levodopa) and meanwhile reduced the mean daily levodopa dose.Citation6,Citation7 Moreover, the combination therapy was supposed to be potentially cost-effective compared with levodopa monotherapy.Citation8 The combination product of levodopa/carbidopa/entacapone (LCE) was approved by the US Food and Drug Administration in 2003 and introduced to the Chinese market in 2013.Citation5 However, no systematic review on its efficacy and safety has been conducted until now, and due to inconsistent evidence on its efficacy, safety, and economy across end points, it has not been covered by medical insurance in China.Citation9,Citation10 The objective of this article is to review the evidence for efficacy, safety, and cost-effectiveness of LCE compared with levodopa/DDCI in the treatment of PD patients.

Methods

Search strategy

We searched PubMed, Embase, Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials, and three Chinese databases – WanFang Data, Chinese Science and Technology Journal Database, and China National Knowledge Infrastructure – from inception to August 2017 for studies that compared LCE and levodopa/DDCI in the treatment of PD. The keywords used in the search were “Parkinson’s disease” for the disease, and terms including “levodopa” “carbidopa” “entacapone” for the medication. We used the Boolean logic “AND” to combine the two sets of terms. We limited the language of articles to English and Chinese only. The systematic review with meta-analysis was registered on Prospero (CRD 42017077349). We also manually searched the reference list of the included studies and ClinicalTrials.gov as a supplementary source for the literature search. Manufacturers of LCE were consulted for unpublished manuscripts.

Study selection and outcome measures

Two independent investigators (ZMY and TTQ) manually screened the references of all retrieved records for potentially eligible studies, through title and abstract screening in the first stage and full-text screening in the second. In the title-and abstract-screening stage, studies appearing to meet the inclusion criteria, potentially relevant, or with insufficient information to make a clear judgment, judged by either investigator or both, were included the in full-text screening process. We obtained full texts of all these studies. We included studies if they had enrolled adults diagnosed with PD,Citation11 compared the efficacy and safety of LCE and levodopa/DDCI with more than ten patients included in each arm, compared the same dosage of levodopa/DDCI in two groups with treatment duration longer than 1 week, and had were randomized controlled trials (RCTs). We resolved disagreements through discussion, and if necessary a third party (NL or SDZ) was consulted.

The primary efficacy outcomes focused on changes in Unified Parkinson’s Disease Rating Scale (UPDRS) scores; among which the UPDRS I subscale measured mental function, the UPDRS II and UPDRS Schwab and England activities of daily living (ADL) subscale measured daily living function, the UPDRS III subscale measured motor function, and the UPDRS IV subscale measured treatment-related complications. The secondary efficacy outcomes included quality of life (QoL), frequency of wearing-off symptoms, safety, and cost-effectiveness. For PD, disease-specific QoL-measurement instruments included the 39-item Parkinson’s Disease Questionnaire (PDQ) 39 and the PDQ8. Wearing-off symptoms may develop further into delayed dose failures or unpredictable fluctuations as the disease progresses.Citation12 Safety outcomes included the incidence of adverse events (AEs) and discontinuation due to AEs.

Data extraction and quality assessment

Data extraction was performed by two independent investigators (ZMY and TTQ) according to a predesigned data-collection form. Extracted information included authors, publication year, participant characteristics (participation-eligibility criteria, sex, and age), intervention information (dosage and duration), outcome of interest, and dropout rate.

The two investigators independently assessed the methodological quality of included studies. We assessed the risk of bias in the eligible RCTs with the Cochrane risk-of-bias assessment tool.Citation13 We evaluated the quality of eligible pharmacoeconomic studies with Consolidated Health Economic Evaluation Reporting Standards.Citation14 In cases of missing data, we contacted study authors for clarification. All disagreements about data extraction and quality assessment were resolved through discussion among all authors.

Statistical analysis

We compared treatment effects through meta-analysis in an intention-to-treat manner (following the allocation of participants in studies). Only the results of studies evaluating similar interventions in similar participants were pooled. We calculated mean differences (MDs) and their 95% CIs for continuous outcomes and RRs for categorical outcomes. For outcomes related to symptom scores or QoL scores, we combined change values from baseline to the last observation. If SDs of change values were not available, we used the recommended method from the Cochrane handbook to estimate them,Citation15 and we converted the SD results of UPDRS scores to SE if needed.Citation16 We calculated RRs and their 95% CIs for all dichotomous data (ie, risk of AEs). We calculated the number needed to harm for potential AEs. We performed meta-analyses with RevMan 5.3 software using a random-effect model. Statistical heterogeneity was assessed with Mantel–Haenszel χ2 and quantified with I2. Sensitivity analysis was conducted by excluding studies that used different effect measures from other studies to test the robustness of the results. Finally, publication bias was examined by funnel plot if the number of included studies ≥10. P<0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Study selection

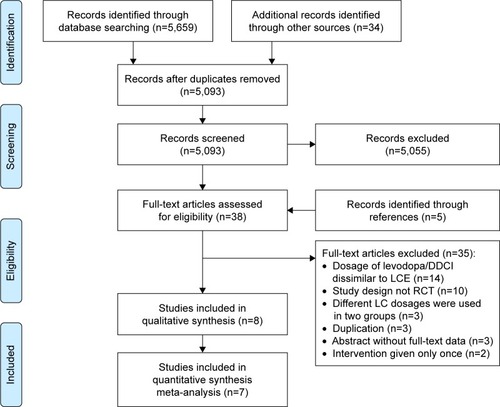

The initial search identified 5,693 relevant records. Of these, 5,055 of 5,093 were excluded after title/abstract screening, and 38 reports were eligible for full-text review. Additionally, five reports were obtained through the references of eligible studies. After full-text review, we excluded 35 reports: 14 studies because dosages of combined levodopa/DDCI and entacapone were different from LCE, ten studies were not RCTs, three studies used different dosages of levodopa/DDCI in two groups, three studies were duplicate reports of included trials, three studies were abstracts without full-text data, and two studies gave treatment only once. Finally, we included seven RCTs with 2,123 PD patients and one pharmacoeconomic study in this systematic review.Citation17–Citation24 The literature-search and study-selection process is presented in .

Study characteristics and quality assessment

Of the seven included RCTs, five compared LCE to levodopa/DDCICitation17–Citation20,Citation23 and two compared the combined treatment of entacapone plus LC (dosages were similar to LCE) to levodopa/DDCI.Citation21,Citation22 Treatment duration ranged from 12 weeks to 134 weeks (). The risk of bias of included studies was generally low, except those by Li et al and Lew et al.Citation21,Citation23 We classified six RCTs at low risk of bias in the domain of random-number generation.Citation17–Citation20,Citation22,Citation23 Five RCTs used the double-blind design and adopted the intention-to-treat principle to analyze data ().Citation17–Citation20,Citation22

Table 1 Characteristics of included studies

Table 2 Risk of bias of randomized controlled trials

Efficacy

UPDRS scores

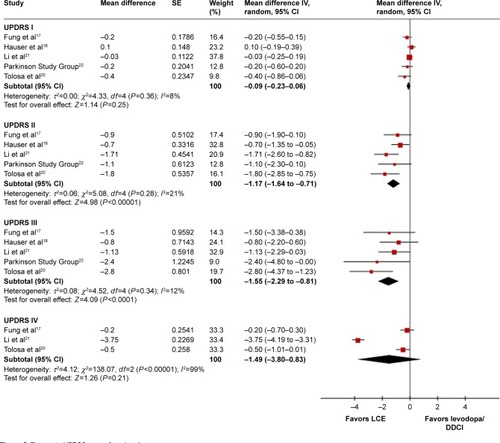

Five studies (1,014 patients) reported the UPDRS I subscale to evaluate mental function. Follow-up ranged from 12 weeks to 39 weeks.Citation17,Citation18,Citation20–Citation22 Meta-analysis showed that the difference in UPDRS I was not statistically different between LCE and levodopa/DDCI (MD −0.09, 95% CI −0.23 to 0.16, P=0.25; I2=8%, P-value for heterogeneity test 0.36).

The same five studies (1,014 patients) evaluated ADL with the UPDRS ADL subscale and UPDRS III to evaluate motor function.Citation17,Citation18,Citation20–Citation22 Meta-analysis showed that LCE had a potential advantage in improving the UPDRS ADL subscale compared to levodopa/DDCI (MD −1.17, 95% CI −1.64 to −0.71, P<0.00001; I2=21%, P-value for heterogeneity test 0.28) and improving UPDRS III (MD −1.55, 95% CI −2.29 to −0.81, P<0.0001; I2=12%, P-value for heterogeneity test 0.34). We did not observe a similar trend for UPDRS IV to evaluate treatment-related complications. With the three studies (386 patients) reporting this outcome, the follow-up was 12 weeks.Citation17,Citation20,Citation21 Meta-analysis showed that there was no difference in UPDRS IV between LCE and levodopa/DDCI (MD −1.49, 95% CI −3.80 to 0.83, P=0.21; I2=99%, P-value for heterogeneity test <0.00001) (). Additionally, two studies (533 patients) evaluated the Schwab and England subscale,Citation18,Citation21 and meta-analysis showed that LCE improved this subscale when compared to levodopa/DDCI (MD 2.05, 95% CI 0.85–3.26, P=0.0008; I2=28%, P-value for heterogeneity test 0.24).

QoL

Four studies (1,282 patients)Citation18–Citation20,Citation23 and two studies (599 patients)Citation17,Citation18 evaluated QoL with the PDQ39 and PDQ8, respectively. Follow-up ranged from 12 weeks to 208 weeks. Meta-analyses showed that there was no difference in the PDQ39 (MD 0.80, 95% CI −1.88 to 3.48, P=0.56; I2=68%, P-value for heterogeneity test 0.03) or PDQ8 (MD −0.70, 95% CI −1.82 to 0.43, P=0.11; I2=58%, P-value for heterogeneity test 0.12) between LCE and levodopa/DDCI. We observed significant heterogeneity across included studies.

Wearing off

Three studies (1,352 patients) reported wearing-off outcomes. Follow-up ranged from 12 weeks to 208 weeks.Citation17–Citation19 The incidence of wearing off in the LCE and levodopa/DDCI groups was 37.2% and 42.5%, respectively. Meta-analysis indicated that wearing-off frequency was not statistically different between LCE and levodopa/DDCI (RR 0.89, 95% CI 0.77–1.02, P=0.10; I2=15%, P-value for heterogeneity test 0.31).

Safety

Serious AEs

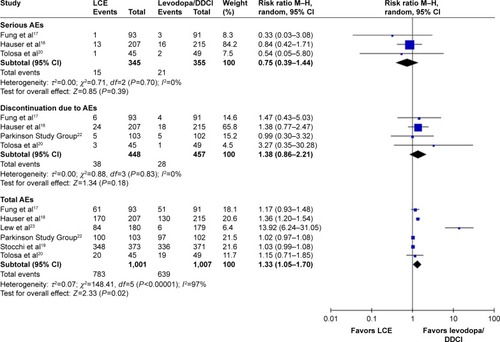

Serious AEs occurred in 4.35% and 5.92% patients in the LCE and levodopa/DDCI groups, respectively. The number needed to harm for the LCE group was 64. Meta-analysis based on three studies (700 patients) indicated that there was no significant difference in risk of serious AEs between LCE and levodopa/DDCI (RR 0.75, 95% CI 0.39–1.44, P=0.39; I2=0, P-value for heterogeneity test 0.70) ().Citation17,Citation18,Citation20

Discontinuation due to AEs

The risk of discontinuation due to AEs was 8.48% and 6.13% for the LCE and levodopa/DDCI groups, respectively. The number needed to harm for the LCE group was 43. Meta-analysis based on four studies (905 patients) indicated that there was no significant difference in risk of discontinuation due to AEs between LCE and levodopa/DDCI (RR 1.38, 95% CI 0.86–2.21, P=0.18; I2=0, P-value for heterogeneity test 0.83) ().Citation17,Citation18,Citation20,Citation22

Total AEs

Risks of total AEs were 78.2% and 63.5% for the LCE and levodopa/DDCI groups, respectively. Meta-analysis based on six studies (2,008 patients) indicated that those on LCE had a higher risk of experiencing AEs compared to levodopa–DDCI (RR 1.33, 95% CI 1.05–1.70, P<0.00001; I2=97%, P-value for heterogeneity test 0.02) ().Citation17–Citation20,Citation22,Citation23

Single AEs

The risk of dyskinesia, urine abnormality, dizziness, nausea, constipation, diarrhea, and sleepiness was 14.5%, 34.0%, 13.2%, 24.2%, 11.1%, 14.3%, and 8.45% in the LCE group compared with 7.7%, 2.94%, 9.42%, 13.8%, 7.96%, 6.26%, and 5.56% in the levodopa/DDCI group, respectively. Meta-analyses indicated that LCE had a higher risk of dyskinesia (four studies,Citation17,Citation19,Citation20,Citation22 1,228 patients, RR 1.80, 95% CI 1.35–2.42; P<0.0001), urine abnormality (three studies,Citation17,Citation18,Citation22 149 patients, RR 9.86, 95% CI 2.95–32.97; P=0.0002), dizziness (five studies,Citation17–Citation20,Citation22 1,649 patients, RR 1.38, 95% CI 1.05–1.82; P=0.02), nausea (five studies,Citation17–Citation20,Citation22 1,649 patients, RR 1.74, 95% CI 1.41–2.13; P<0.00001), and diarrhea (three studies,Citation17,Citation19,Citation20 105 patients, RR 2.24, 95% CI 1.51–3.32; P<0.0001) than levodopa/DDCI. There was no significant difference in the risk of constipation (four studies,Citation17–Citation19,Citation22 148 patients, RR 1.38, 95% CI 0.99–1.91; P=0.05) or sleepiness (two studies,Citation19,Citation20 838 patients, RR 1.34, 95% CI 0.85–2.12; P=0.21) between the two groups. Significant heterogeneity was found between studies reporting outcomes of urine abnormality (I2=68%, P-value for heterogeneity test 0.04).

Economy

The only cost–utility analysis using a Markov model found indicated that LCE was beneficial to individual patients and the incremental cost-effectiveness ratio of LCE was £3,105 per quality-adjusted life-year (QALY) gained (<£30,000 per QALY gained, within the range considered to indicate acceptable cost-effectiveness) compared with traditional levodopa/DDCI therapy in the UK over a period of 10 years.Citation24 What is more, LCE gained an average 1.04 QALYs and reduced direct costs by £10,198 per patient in 10 years from the UK perspective. Sensitivity analyses confirmed the results were robust when different discount rates or a 5-year shorter time horizon was applied.

Sensitivity analysis

Only one study, by the Parkinson Study Group, did not clearly explain that MD was used as an effect measure, although changes in UPDRS scores were reported in tables.Citation22 Therefore, the sensitivity analysis was performed excluding this study. No significant changes in the results of UPDRS I (MD −0.08, 95% CI −0.25 to 0.10; P=0.39), UPDRS II (MD −1.21, 95% CI −1.78 to −0.64; P<0.0001), or UPDRS III (MD −1.48, 95% CI −2.31 to −0.64; P=0.0006) were indicated, although the heterogeneity among studies was increased in these outcomes. For Stocchi et al, we used scores from ClinicalTrials.gov that were different from the data published in the paper.Citation19 No significant changes in the results were indicated when the different data were used.

Discussion

The meta-analysis of RCTs indicated that LCE therapy improved UPDRS II, UPDRS III, and Schwab and England ADL scores for PD patients when compared with levodopa/DDCI therapy. However, there was no difference in UPDRS I, UPDRS IV, frequency of wearing off, PDQ39, or PDQ8 scores. LCE therapy increased the risk of total AEs, motor disturbance, nausea, and diarrhea, but did not increase the risk of serious AEs or discontinuation risk when compared with levodopa/DDCI therapy.

Most of these results are in line with clinical observations in the published paper, except for QoL data. The UPDRS offers a comprehensive evaluation of four relevant dimensions in PD: mentation, behavior, and mood (UPDRS I), ADL (UPDRS II), motor examination (UPDRS III), and complications (UPDRS IV).Citation25 In a pooled analysis of published Phase III studies on 808 PD patients, entacapone showed promising results in UPDRS II (P<0.01) and III (P<0.01) scores.Citation26 A meta-analysis of 14 studies also indicated adjuvant treatment with entacapone improved UPDRS ADL and motor scores.Citation27 Considering the fact that entacapone can increase levodopa sustainability by extending the drug’s half-life, it was reasonable to find that LCE improved scores of UPDRS II and UPDRS III in our study, which is also consistent with previous findings. Three published RCTs with a minimum 3-month follow-up suggested that levodopa with entacapone had a slightly beneficial effect on patient QoL, but at a low level.Citation28 In this meta-analysis, LCE did not show any improvement in PDQ39 or PDQ8 scores. This may be explained by the relatively small samples and short follow-up of included studies. Moreover, nonmotor symptoms can influence QoL even more than motor symptoms, and levodopa influences few nonmotor symptoms. There is a likelihood that patients with relatively earlier and milder diseases experience a higher impact on QoL, and thus heterogeneity in the characteristics of included patients may also have contributed to these nonsignificant results. This study suggested that there was a trend for less wearing off in the LCE group than in LC, although it failed to reach statistical significance. Inconsistently with our study, previous studies assessing wearing-off time demonstrated a substantial reduction in for the LCE group, but not for the LC group.Citation29,Citation30 In the included studies, we reported no statistical difference in the incidence of wearing-off between LCE and LC. Given the fact that entacapone prolongs the response to levodopa, we cannot exclude the possibility that a difference in effect on duration was not captured by the included studies.

In terms of adverse reactions, LCE was generally well tolerated compared with levodopa/DDCI, with no significant difference in serious AEs or discontinuation due to AEs found between the two groups. Risks of total AEs and single AEs were higher in the LCE group, but all were noted in the package insert and published articles on entacapone.Citation27 Such adverse reactions to entacapone are supposed to be associated with enhanced dopamine activity. Urine abnormality was the most commonly reported AE in the LCE group, but this is a benign event related to the color of entacapone metabolites eliminated in the urine. As for economy, only one study with a cost–utility analysis showed that LCE had favorable cost-effectiveness. Therefore, further studies are needed to confirm these observations.

The results are consistent with those of the only found health-technology assessment, by the Canadian Agency for Drugs and Technologies in Health, published in 2008.Citation31 However, this report included only two RCTs and indicated that LCE showed significant improvement in UPDRS motor scores when compared with levodopa/DDCI in PD patients with mild motor fluctuations, and the statement that LCE would be less costly was not based on economy analysis. LCE compound preparations allow PD patients to use a COMT inhibitor earlier and reduce the dose of levodopa, which can provide a modest clinical benefit over levodopa/DDCI for up to 5 years.Citation32

To the best of our knowledge, this study is the first systematic review and meta-analysis to compare LCE with levodopa/DDCI for PD patients. We included high-quality RCTs to ensure the rigor of the systematic review process and the relevance of results in the following aspects. First, compared with the single-study data presented in the guidelines and recommendations,Citation5,Citation10 this study used systematic literature-search methods in an attempt to include all relevant studies and reduce publication bias. Conducting meta-analysis for data synthesis can give us a quantitative estimation of outcomes of interest, thus providing the best evidence available to make up for the deficiencies of existing guidelines. We further performed pharmacoeconomic evaluations to get a more comprehensive view of LCE, which could not be seen in previous meta-analyses. Although there has been a published meta-analysis on ten drugs for PD, no comparisons on compound formulations, such as LCE or levodopa/DDCI, were made.Citation33 Second, during the course of the study, the authors of the study continued to check the references of included literature, contact the authors, consult the manufacturers, and search ClinicalTrials.gov for unpublished data. For example, the UPDRS I data after treatment in Fung et alCitation17 were extracted from ClinicalTrials.gov.Citation34 Third, the literature included not only took into account the formulation of the LCE compound but also similar dosages of levodopa/carbidopa plus entacapone, taking into account the bioequivalence between drugs demonstrated by a series of pharmacokinetic studies,Citation35 so this study further expanded research sources and enriched the research data. Fourth, the study comprehensively pooled outcome data and objectively evaluated advantages and disadvantages of LCE, which could provide useful information for decision-making for appropriate LCE target patients.

Our study has some limitations. First, the number of studies included was limited, and thus no further subgroup analysis of early PD patients or PD patients with dyskinesia was done. It is expected that more research will be published in future further to differentiate between the two subpopulations. Second, we were unable to conduct further subgroup analysis for different courses of treatment. Considering the potential of the LCE compound to improve patient adherence and benefit in maintaining function in patients receiving chronic oral levodopa therapy,Citation36 longer treatment duration may link to better outcomes. However, we lacked the ability to test this hypothesis with available data, due to the relatively short follow-ups in the included studies. Furthermore, only English-language and Chinese-language studies were included. We tried to include important conference abstracts in the databases search, but we failed to find relevant studies. Thirdly, due to the four primary outcomes (UPDRS I–IV) included, the possibility of an increase in false-positive test results could not be ruled out.

In summary, LCE therapy can improve PD patients’ symptoms by improving UPDRS II, UPDRS III, and Schwab and England ADL scores for PD patients when compared with levodopa/DDCI therapy. As for safety, LCE therapy was associated with higher risks of total AEs and single AEs, including dyskinesia, urine abnormality, dizziness, nausea, diarrhea, and sleepiness but did not increase the risks of serious AEs or discontinuation from studies.

Acknowledgments

We extend special thanks to Professor Robert A Hauser from the USF Health Byrd Parkinson’s Disease and Movement Disorders Center, Professor Nick Holford from the University of Auckland, Professor Victor Fung from the University of Sydney, and Professor Heinz Reichmann from the University of Dresden for kind help with better understanding of their publications. We would like to thank Wen-Xi Liu from Peking University Third Hospital for help with editing. This study was funded by the Beijing Pharmaceutical Association and Eisai China Inc. At no point did Eisai China attempt to influence the manuscript. This manuscript was invited to be presented orally in the 27th National Hospital Pharmacy Annual Academic Conference in China, and won first prize.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- GrimesDGordonJSnelgroveBCanadian guidelines on Parkinson’s diseaseCan J Neurol Sci201239S1S30

- KaliaLVLangAEParkinson’s diseaseLancet201538689691225904081

- ConnollyBSLangAEPharmacological treatment of Parkinson disease: a reviewJAMA20143111670168324756517

- RichyFFPietriGMoranKASeniorEMakaroffLECompliance with pharmacotherapy and direct healthcare costs in patients with Parkinson’s disease: a retrospective claims database analysisAppl Health Econ Health Policy20131139540623649891

- PoulopoulosMWatersCCarbidopa/levodopa/entacapone: the evidence for its place in the treatment of Parkinson’s diseaseCore Evid2010511020694135

- StocchiFHsuAKhannaSComparison of IPX066 with carbidopa-levodopa plus entacapone in advanced PD patientsParkinsonism Relat Disord2014201335134025306200

- BrooksDJSagarHEntacapone is beneficial in both fluctuating and non-fluctuating patients with Parkinson’s disease: a randomized, placebo controlled, double blind, six month studyJ Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry2003741071107912876237

- Rodríguez-BlázquezCForjazMJLizánLPazSMartínez-MartínPEstimating the direct and indirect costs associated with Parkinson’s diseaseExpert Rev Pharmacoecon Outcomes Res20151588991126511768

- FoxSHKatzenschlagerRLimSYThe Movement Disorder Society evidence-based medicine review update: treatments for the motor symptoms of Parkinson’s diseaseMov Disord201126S2S4122021173

- FerreiraJJKatzenschlagerRBloemBRSummary of the recommendations of the EFNS/MDS-ES review on therapeutic management of Parkinson’s diseaseEur J Neurol20132051523279439

- HughesAJDanielSEKilfordLLeesAJAccuracy of clinical diagnosis of idiopathic Parkinson’s disease: a clinico-pathological study of 100 casesJ Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry1992551811841564476

- ReichmannHEmreMOptimizing levodopa therapy to treat wearing-off symptoms in Parkinson’s disease: focus on levodopa/carbidopa/entacaponeExpert Rev Neurother20121211913122288667

- HigginsJPAltmanDGGøtzschePCThe Cochrane collaboration’s tool for assessing risk of bias in randomized trialsBMJ2011343d592822008217

- HusereauDDrummondMPetrouSConsolidated Health Economic Evaluation Reporting Standards (CHEERS) statementValue Health201316e1e523538200

- HigginsJPGreenSCochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions Version 5.1.0Hoboken (NJ)Wiley2011

- SedgwickPStandard deviation or the standard error of the meanBMJ2015350h83125691433

- FungVSHerawatiLWanYQuality of life in early Parkinson’s disease treated with levodopa/carbidopa/entacaponeMov Disord200924253118846551

- HauserRAPanissetMAbbruzzeseGDouble-blind trial of levodopa/carbidopa/entacapone versus levodopa/carbidopa in early Parkinson’s diseaseMov Disord20092454155019058133

- StocchiFRascolOKieburtzKInitiating levodopa/carbidopa therapy with and without entacapone in early Parkinson disease: the STRIDE-PD studyAnn Neurol201068182720582993

- TolosaEHernándezBLinazasoroGEfficacy of levodopa/carbidopa/entacapone versus levodopa/carbidopa in patients with early Parkinson’s disease experiencing mild wearing-off: a randomised, double-blind trialJ Neural Transm (Vienna)201412135736624253234

- LiJHeJJYiRWangHEWuJJA clinical study of levodopa/carbidopa combined with entacapone in Parkinson’s diseaseXian Dai Sheng Wu Yi Xue Jin Zhan201616504506

- No authors listedEntacapone improves motor fluctuations in levodopa-treated Parkinson’s disease patientsAnn Neurol1997427477559392574

- LewMFSomogyiMMcCagueKWelshMImmediate versus delayed switch from levodopa/carbidopa to levodopa/carbidopa/entacapone: effects on motor function and quality of life in patients with Parkinson’s disease with end-of dose wearing offInt J Neurosci201112160561321843110

- FindleyLJLeesAApajasaloMPitkänenATurunenHCost-effectiveness of levodopa/carbidopa/entacapone (Stalevo) compared to standard care in UK Parkinson’s disease patients with wearing-offCurr Med Res Opin2005211005101416004667

- BhidayasiriRMartinez-MartinPClinical assessments in Parkinson’s disease: scales and monitoringInt Rev Neurobiol201713212918228554406

- KuoppamäkiMVahteristoMEllménJKieburtzKPooled analysis of phase III with entacapone in Parkinson’s diseaseActa Neurol Scand201413023924725186800

- LiJLouZLiuXSunYChenJEfficacy and safety of adjuvant treatment with entacapone in advanced Parkinson’s disease with motor fluctuation: a systematic meta-analysisEur Neurol20177814315328813703

- Martinez-MartinPRodriguez-BlazquezCForjazMJKurtisMMImpact of pharmacotherapy on quality of life in patients with Parkinson’s diseaseCNS Drugs20152939741325968563

- BrooksDJAgidYEggertKWidnerHØstergaardKHolopainenATreatment of end-of-dose wearing-off in Parkinson’s disease: Stalevo (levodopa/carbidopa/entacapone) and levodopa/DDCI given in combination with Comtess/Comtan (entacapone) provide equivalent improvements in symptom control superior to that of tradition levodopa/DDCI treatmentEur Neurol20055319720215970632

- KollerWGuarnieriMHubbleJRabinowiczALSilverDAn open-label evaluation of the tolerability and safety of Stalevo (carbidopa, levodopa and entacapone) in Parkinson’s disease patients experiencing wearing-offJ Neural Transm (Vienna)200511222123015503197

- Canadian Agency for Drugs and Technologies in HealthCommon drug review: carbidopa, levodopa and entacapone2008 Available from: https://www.cadth.ca/sites/default/files/cdr/complete/cdr_complete_Stalevo_October-2008.pdfAccessed November 20, 2017

- NissinenHKuoppamäkiMLeinonenMSchapiraAHEarly versus delayed initiation of entacapone in levodopa-treated patients with Parkinson’s disease: a long-term, retrospective analysisEur J Neurol2009161305131119570145

- ZhuoCZhuXJiangRComparison for efficacy and tolerability among ten drugs for treatment of Parkinson’s disease: a network meta-analysisSci Rep201784586528374775

- Novartis [webpage on the Internet]A randomized, double-blind, parallel-group, multi-national study to compare the effect on quality of life of levodopa/carbidopa/entacapone with levodopa/carbidopa in patients with Parkinson’s disease with no or minimal non-disabling motor fluctuations2007 Available from: https://www.novctrd.com/CtrdWeb/displaypdf.nov?trialresultid=2366Accessed November 20, 2017

- HauserRALevodopa/carbidopa/entacapone (Stalevo)Neurology200462S64S7114718682

- DeleaTEThomasSKHagiwaraMMancioneLAdherence with levodopa/carbidopa/entacapone versus levodopa/carbidopa and entacapone as separate tablets in patients with Parkinson’s diseaseCurr Med Res Opin2010261543155220429819