Abstract

Objective

Variceal hemorrhage is the primary driver of mortality in patients with portal hypertension. Recent guidelines recommended that patients with esophageal varices should receive endoscopic band ligation (EBL) or carvedilol as prophylaxis of variceal bleeding. Several clinical trials have compared carvedilol use with EBL intervention, yielding controversial results. The present study aimed to perform a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials (RCTs) evaluating the benefits and harms of carvedilol vs EBL for the prevention of variceal bleeding.

Methods

Studies were searched on Pubmed, Embase, Medline, and Cochrane library databases up to August 2018. Main outcomes in selected studies (variceal bleeding, all-cause deaths, bleeding-related deaths, and adverse events) were pooled into a meta-analysis.

Results

Seven RCTs were identified in this meta-analysis, including a total of 703 patients. A total of 359 patients were randomized to carvedilol group and 354 were randomized to EBL group. No significant difference in variceal bleeding was observed between carvedilol use and EBL groups (relative ratio [RR] =0.86, 95% CI =0.60–1.23, I2=11%), without publication bias. No significant difference was found neither for all-cause deaths (RR =0.82, 95% CI =0.44–1.53, I2=66%) nor for bleeding-related deaths (RR =0.85, 95% CI =0.39–1.87, I2=42%) in four included studies. Moreover, no reduced trend was observed toward adverse events in carvedilol group compared with that in EBL group (RR =1.32, 95% CI =0.75–2.31, I2=81%).

Conclusion

There is no significant difference between carvedilol use and EBL intervention for the prophylaxis of variceal bleeding in patient with esophageal varices. Large-scale clinical trials are further needed to make a confirmed conclusion.

Introduction

Variceal hemorrhage is one of the most lethal complications of portal hypertension.Citation1 One-third of patients with esophageal varices will develop gastrointestinal bleed, and the risk of bleeding is correlated with increased high hepatic venous pressure gradient (HVPG).Citation2 Therefore, in order to reduce mortality, it is of great significance to prevent variceal hemorrhage in the clinical management of patients with cirrhosis.

Among several recommended strategies, the most proposed treatment options are non-selective beta-blockers (NSBB) and endoscopic band ligation (EBL).Citation3 In clinical practice, <50% of patients with liver cirrhosis are sensitive to propranolol or nadolol with regard to hemodynamic aspects.Citation4 Carvedilol, a third generation of NSBB, has been shown to possess an additional property of vasodilatation due to its intrinsic anti-α adrenergic activity.Citation5 Carvedilol can effectively reduce cardiac output and splanchnic blood flow, while the action on α1 receptor leads to splanchnic vasoconstriction, decreasing HVPG and the incidence of related complications.Citation6 Studies have demonstrated that carvedilol is superior to the traditional NSBB – propranolol, in reducing portal pressure.Citation1,Citation7 In a meta-analysis based on five high-quality randomized controlled trials (RCTs), the proportion of patients with the use of carvedilol was much higher in achieving a target hemodynamic response (reduction ≥20% of baseline or to ≤12 mmHg) compared with those with propranolol.Citation8

Accumulating evidences indicate that endoscopic techniques are the effective intervention to prevent variceal bleeding in patients with severe or moderate varices.Citation9 Compared with endoscopic injection sclerotherapy, EBL is a purely mechanical method of eradicating varices, with fewer endoscopic sessions and less frequent complications.Citation10 Recently, several clinical trials have compared the effects of carvedilol with EBL for the primary or secondary prevention of variceal bleeding in patients with portal hypertension. However, the results from these trials were inconsistent. Therefore, we initiated this meta-analysis described here to assess the efficacy and safety of carvedilol use compared with EBL intervention for the prevention of variceal bleeding.

Methods

This protocol was registered on the website of PROSPERO and the registration number was CRD42018106699.

Study eligibility

Inclusion criteria: 1) study design: prospective RCTs; 2) participants: patients with a confirmed diagnosis of esophageal varices by endoscopy; 3) treatment group: carvedilol use; 4) comparison group: EBL intervention; and 5) outcomes: variceal bleeding, all-cause deaths, bleeding-related deaths, and adverse events.

Exclusion criteria: 1) studies that assessed the efficacy of carvedilol without controlled group; 2) retrospective clinical trials, letters to the editor, reviews, and case reports; and 3) studies published in languages other than English.

Search strategy

Pubmed, Embase, Medline, and The Cochrane Library were searched up to August 2018 to identify potential references by two independent investigators (Xuemei Jia and Yingyun Guo). Databases were searched through the following search terms: “carvedilol” AND “endoscopic band ligation”. A manual search of the reference lists of related studies was also conducted by the two investigators. The database search was confined to clinical trials published in English language.

Data extraction and quality assessment

Data from the included studies were extracted by two independent researchers (Shan Tian and Ruixue Li). The following information was extracted from the selected studies: author, year, study period, number of patients, age, sex, presence of ascites, Child–Pugh class, follow-up time, and outcomes. It was decided to resolve any discrepancies through another investigator’s final determination (Weiguo Dong). The guidelines of the Cochrane Handbook of Systematic Reviews of Interventions were applied to evaluate the quality assessment of included studiesCitation11 by the two researchers. The following items were assessed for every selected trial: random sequence generation, allocation concealment, blinding of participants and personnel, blinding of outcome assessment, incomplete outcome data, selective reporting, and other bias. For each item, the risk of bias was evaluated as either low, high, or unclear.

Statistical methods

Relative ratios (RRs) with 95% CIs were applied to calculate with respect to dichotomous data. By using Review Manager software (RevMan, V.5.3, Copenhagen, Denmark, 2014),Citation11 we performed statistical analysis according to the guidelines of the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions. We calculated the χ2 and I2 statistics to detect the heterogeneity among included studies. As for I2 statistic,Citation12 25%–50%, 50%–75%, and >75% were separately regarded as low, moderate, and high heterogeneity. Random-effects model was used if substantial heterogeneity across studies was detected; otherwise, a fixed-effects model was adopted. Finally, potential reasons for heterogeneity were probed if significant heterogeneity was found. P<0.05 was regarded as statistically significant.

Results

Study identification and selection

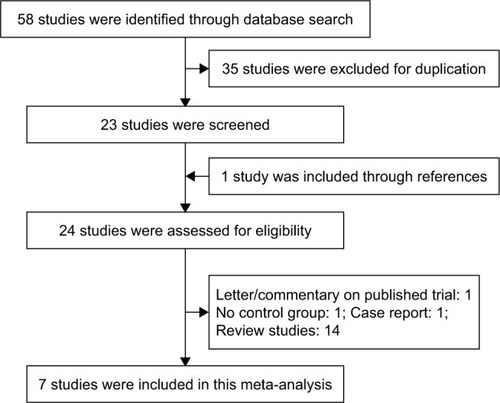

Our search identified 58 potential references through database search. A total of 35 reports were excluded due to duplication of publication. A total of 23 studies were considered for further analysis, and one study was added to our meta-analysis through reference lists.Citation13 One study was a case reportCitation14 and one was a letter to the editor.Citation15 One high-quality trial evaluated the effect of carvedilol in decreasing portal pressure without controlled group. Besides, 14 references were published as a form of review or meta-analysis. Finally, seven RCTs were included in the quantitative synthesis. The detailed flow diagram of the study selection process is shown in .

Description of included studies

Seven prospective RCTs were identified in our meta-analysis,Citation13,Citation16–Citation21 including 713 cases (359 patients in carvedilol group and 354 in EBL group) of patients with portal hypertension. The characteristics of the seven included trials are listed in . The studies were conducted in Egypt (n=3),Citation13,Citation18,Citation19 UK (n=2),Citation20,Citation21 Pakistan (n=1),Citation17 and Austria (n=1).Citation16 Six studies compared the efficacy and safety of carvedilol with EBL for prevention of the first variceal bleeding, while only one study compared the effects of carvedilol with EBL for the prevention of variceal rebleeding.Citation20 As shown in , these trials were conducted from 2000 to 2016. The mean age of participants ranged from 47.2 to 55 years, with a majority of male patients (59%) when the gender ratio was reported in six studies.Citation13,Citation16–Citation18,Citation20,Citation21 Four studies reported that the etiology of portal hypertension was chronic viral cirrhosis,Citation13,Citation16,Citation17,Citation19 while three trials demonstrated that alcohol liver disease was the primary reason for cirrhosis.Citation18,Citation20,Citation21 The most common complication of cirrhosis – ascites, was reported in six studies. A total of 43.34% of included patients (270/623) had concomitant ascites with different severity. Moreover, six trials applied the percentage of Child–Pugh class (A/B/C) to assess the liver function and the majority of patients were found to be class B or C (69.03%).Citation13,Citation16–Citation19,Citation21 However, only one study used the form of mean (IQR) to represent the score of Child–Pugh class and the mean score was 9 (7.0–10.5) in carvedilol group and 9 (8.0–11.0) in EBL group.Citation20 The mean time of follow-up ranged from 12 to 26.3 months. In general, the baseline features of included patients in carvedilol and EBL groups were basically comparable.

Table 1 Clinical features of patients in the included studies

Treatment protocols

Carvedilol was administered orally in patients in carvedilol group (n=359) in the seven studies. Patients in four studies were given a tablet of 6.25 mg/day and then slowly increased to 12.5 mg/day if tolerated. However, in one trial, patients in the carvedilol group were given a starting dosage of 6.25 mg/day, then increased to 12.5–50 mg/day to achieve a reduction in baseline heart rate by 25% but over 55 beats/min.Citation18 Another two clinical trials used 25 mg/day as long-run dose if patients could tolerate.Citation13,Citation16 The endpoint of EBL in all included studies was obliteration of varices except for one trial, which defined endpoint of EBL as esophageal varices being either grade I or complete obliteration.Citation19 The interval of EBL in selected studies varied from 2 to 4 weeks.

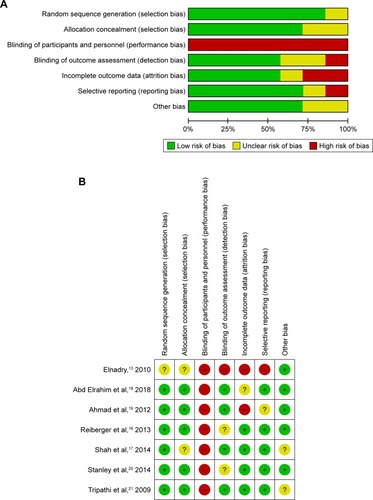

Among seven included trials, five studies were associated with a low risk of bias,Citation16–Citation18,Citation20,Citation21 one studyCitation19 was assessed as unclear risk of bias, and one trial was evaluated as high risk of bias.Citation13 shows the quality of the included studies as assessed by Review Manager software.

Outcome measures

Variceal bleeding

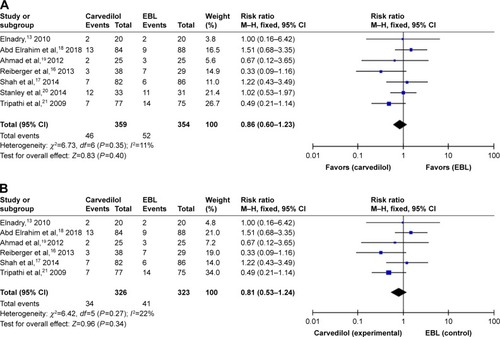

Seven studies evaluated variceal bleeding as an outcome measure. A total of 46 patients had variceal hemorrhage in the carvedilol group (12.81%), while 52 patients had it in the EBL group (14.69%). The rate of variceal bleeding ranged from 5% to 36.4% for patients with carvedilol use, and from 10% to 35.5% in patients with EBL. Four clinical trials showed that the carvedilol group had lower variceal bleeding rate than the EBL group. However, two studies demonstrated that variceal bleeding rate was lower in EBL group than in carvedilol group.Citation18,Citation20 Only one trial reported that variceal bleeding rate was equal in two groups.Citation19 When we pooled the outcome of variceal bleeding into meta-analysis, no significant difference was noted between two groups (RR =0.86, 95% CI =0.60–1.23), as shown in . Moreover, statistical test indicated that the studies did not have significant heterogeneity (I2=11%, P=0.35). Therefore, the results were calculated according to the fixed-effect method. There was no evidence of publication bias through the funnel plot ().

Figure 3 Fixed-effect model of variceal bleeding.

Abbreviation: EBL, endoscopic band ligation.

Figure 4 Funnel plot of carvedilol use vs EBL.

Abbreviations: EBL, endoscopic band ligation; RR, risk ratio.

However, in the seven selected trials, only one study assessed variceal rebleeding as an outcome measure.Citation20 So, we performed a subgroup analysis through first and second prevention of variceal bleeding. Six studies evaluated first prevention of hemorrhage as an outcome measure. No significant difference was observed through the fixed-effect model (RR =0.81, 95% CI =0.53–1.24, I2=22%, ). No evidence of publication bias was detected through the funnel plot (). As for the second prevention of hemorrhage, only one trial reported that 64 cases of patients with portal hypertension were randomized to this multicenter study.Citation20 Variceal rebleeding occurred in 12 patients (36.4%) in the carvedilol group and 11 patients (35.5%) in the EBL group. However, this difference was also not significant according to the chi-squared test (P=0.857).

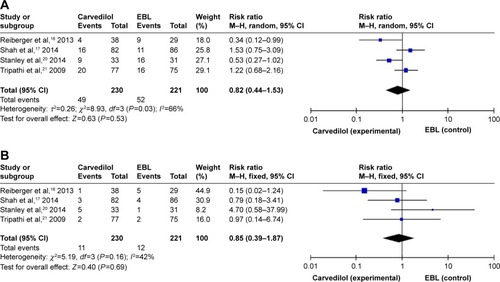

All-cause and bleeding-related deaths

Three trials did not report the all-cause and bleeding-related deaths due to the relatively short follow-up time (12 months).Citation16,Citation18,Citation19 There were 49 deaths (21.30%) in the carvedilol group and 52 (23.53%) in the EBL group. There was no significant difference in the incidence of all-cause deaths between carvedilol and EBL groups (RR =0.82, 95% CI =0.44–1.53, ). Due to the significant heterogeneity in the four studies (I2=66%, P=0.03), the random-effect model was applied. Moreover, bleeding-related deaths were also assessed as an outcome measure to compare the safety of carvedilol use vs EBL intervention. The number of patients who died from bleeding in carvedilol group (12/230) was equal to that in the EBL group (12/221). When we pooled this outcome into meta-analysis, we found that no significant difference was noted between two groups (RR =0.85, 95% CI =0.39–1.87), as shown in . No obvious heterogeneity (I2=42%, P=0.16) was detected through statistical tests.

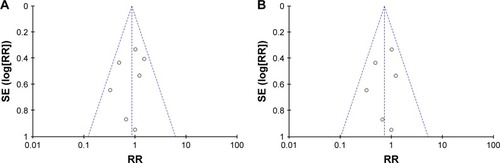

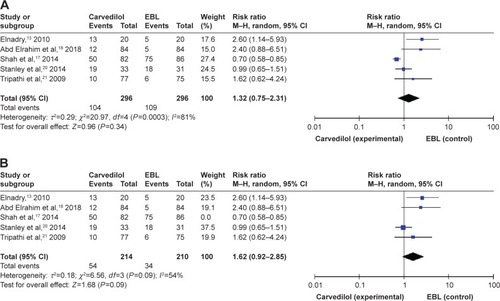

Adverse events

Adverse events were confined to side effects of carvedilol or EBL, not related to the progression of chronic liver disease or symptoms of variceal bleeding. Five studies have reported the adverse events.Citation13,Citation17,Citation18,Citation20,Citation21 A total of 104 adverse events (104/296) occurred in the carvedilol group, while 109 (109/296) occurred in the EBL group, as shown in . Although the adverse events were different in every included study, the vast majority was systematic hypotension in the carvedilol group and chest pain caused by mechanical injury in the EBL group. We tried to pool adverse events into meta-analysis and this index did not show any significant difference between two groups (RR =1.32, 95% CI =0.75–2.31, ). Due to the obvious heterogeneity (I2=81%, P=0.0003), we conducted sensitivity analysis by excluding one study at a time and recalculating the pooled RRs for the remaining four studies. When we excluded Shah et alCitation17 2013, we found that the heterogeneity was significantly decreased (I2=54%, P=0.09, ). This trial divided adverse events into serious adverse events (2 in carvedilol group and 18 in EBL group) and non-serious adverse events (48 in carvedilol group, 58 in EBL group).Citation17 The heterogeneity was moderate and not low even after sensitivity analysis due to the diversity of adverse events reported in five clinical trials.

Figure 6 Forest plots of adverse events.

Abbreviation: EBL, endoscopic band ligation.

Table 2 Outcomes reported in the included studies

Discussion

Portal hypertension causes some fatal complications in patients with liver cirrhosis, such as variceal bleeding and hepatic encephalopathy. Prevention options of variceal bleeding with higher efficacy, less side effects, and lower cost are urgently needed in the clinical management of patients with portal hypertension.Citation22,Citation23 Currently, most meta-analysis was focused on comparing the efficacy of propranolol with EBL,Citation9,Citation24,Citation25 or comparing the efficacy and safety of carvedilol with pro-pranolol.Citation8 As this newer NSBB was widely used in the prevention of variceal bleeding with fewer side effects and better tolerance in contrast to propranolol, it is significant to explore the question as follows: whether carvedilol use is more suitable for prevention of variceal bleeding than EBL intervention.

To our knowledge, this is the first meta-analysis to date comparing carvedilol use with EBL intervention for the prevention of esophageal variceal bleeding. From the seven included studies, we observed that the rate of variceal bleeding was lower in carvedilol group than in EBL group. However, there was no significant difference from the forest plot (RR =0.86, 95% CI =0.60–1.23, I2=11%).

Carvedilol is a potent portal hypotensive agent with additional anti-α1 receptor activity, which is widely applied in the management of portal hypertension, hypertension, heart failure, and ischemic heart disease. Study has shown that carvedilol reduces portal pressure not only through lowering portal-collateral blood flow (as propranolol) but also through decreasing the hepatic vascular resistance.Citation4 The superiority of carvedilol over propranolol in reducing HVPG is associated with the α1 blocking effect, which could reduce intra-hepatic resistance.Citation26 Moreover, recent studies have demonstrated that this agent possesses antioxidant properties, exerts beneficial effects on mitochondrial function, and could decrease the resistance of insulin.Citation27–Citation29 Hence, the comprehensive mechanisms of action of carvedilol make it a promising agent for the prevention of variceal bleeding in patients with cirrhosis.

Our meta-analysis did not show additional benefits of carvedilol over EBL, neither for the first prevention nor the second prevention of esophageal variceal bleeding. The fact that no significant difference is observed between the two options with regard to variceal bleeding does not necessarily indicate that the two kinds of therapy are equally effective. Carvedilol could reduce portal pressure with fewer complications, while EBL is a kind of invasive intervention without changing the potential pathophysiological mechanisms and only last for a short period of time. A retrospective study demonstrated that carvedilol was not associated with increased risk of mortality in decompensated cirrhosis patients and long-term carvedilol therapy could improve the survival of patients with cirrhosis.Citation30 Moreover, a prospective study conducted by Kirnake et al showed that 76% patients maintained their hemodynamic response to carvedilol through intention-to-treat analysis and carvedilol treatment was associated with favorable clinical survival in patients with portal hypertension.Citation4 Possible reasons that the benefits of carvedilol in the prevention of variceal bleeding did not translate into decreased rate of variceal bleeding are as follows: first, carvedilol is a potent portal hypotensive agent with multiple effects and these effects will be more obvious in the long run. However, most included studies have followed up for 1–2 years and three trials have followed up only for 1 year. Second, over the past decades, EBL technique has been well grasped by more and more clinicians and the higher variceal eradication rate in the EBL group may signify the lower variceal bleeding rate.

We have noted that carvedilol did not gain additional benefits in reducing adverse events as compared to EBL for the prevention of variceal bleeding. From the five included studies, we found that adverse effects occurred with similar incidence both in the carvedilol and the EBL groups. In carvedilol group, the most common serious adverse event was symptomatic hypotension. No patient in carvedilol group was reported to experience serious sodium-water retention after the use of carvedilol. However, the incidence of symptomatic hypotension due to the use of carvedilol will be decreased by starting at a very low dose (6.25 mg/day) and careful titration by gradually increasing up to 12.5 mg/day. Maharaj et al hold the view that the typical threshold for carvedilol toxicity in overdose is 50 mg.Citation14 Moreover, hemodynamic monitoring is useful to reduce the incidence of symptomatic hypotension during the period of carvedilol use. Chest pain was the most common serious adverse event in EBL group, followed by esophageal ulcer. These complications in EBL group often require urgent hospitalization and could be lethal if not handled properly. However, the evaluation of adverse events in meta-analysis of included trials is often difficult due to lack of a unified definition, which is more likely to cause no significant difference of adverse events between two groups.Citation30

Several limitations still exist in our meta-analysis. First, we cannot deny the fact that the quality of some selected studies was relatively low. As carvedilol is easily differentiate from EBL operation for patients, it is hard to perform blinding for trials. Subsequently, with respect to subgroup analysis according to first and second prevention, we cannot perform a meta-analysis of second prevention due to only one available study. Third, the selected references had varying designs, including differences in dose of carvedilol, frequency of EBL, and follow-up time, which may affect the outcomes of the selected trials.

Conclusion

Our study demonstrates that no significant difference exists between carvedilol use and EBL groups in the prophylaxis of variceal bleeding. High-quality clinical trials with adequate bias control and sufficient follow-up are required in order to determine the long-term effects of both treatments.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by grants from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No 81602535).

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- TripathiDHayesPCThe role of carvedilol in the management of portal hypertensionEur J Gastroenterol Hepatol201022890591120093937

- Garcia-TsaoGAbraldesJGBerzigottiABoschJPortal hypertensive bleeding in cirrhosis: risk stratification, diagnosis, and management: 2016 practice guidance by the American Association for the Study of Liver DiseasesHepatology201765131033527786365

- YangLHanGHRevising consensus in portal hypertension: report of the Baveno V consensus workshopJ Clin Hepatol2011272116118

- KirnakeVAroraAGuptaVHemodynamic response to carvedilol is maintained for long periods and leads to better clinical outcome in cirrhosis: a prospective studyJ Clin Exp Hepatol20166317518527746613

- KimHYJungYJSoYHWooHKimWNoninvasive prediction of hemodynamic response to carvedilol therapy for primary prophylaxis in cirrhotic patients with esophageal varices: a prospective studyJ Hepatol2017661S47

- TripathiDTherapondosGLuiHFStanleyAJHayesPCHaemodynamic effects of acute and chronic administration of low-dose carvedilol, a vasodilating beta-blocker, in patients with cirrhosis and portal hypertensionAliment Pharmacol Ther200216337338011876689

- SilkauskaitėVKupčinskasJPranculisAJonaitisLPetrenkienėVKupčinskasLAcute and 14-day hepatic venous pressure gradient response to carvedilol and nebivolol in patients with liver cirrhosisMedicina2013491173

- SinagraEPerriconeGD’AmicoMTinèFD’AmicoGSystematic review with meta-analysis: the haemodynamic effects of carvedilol compared with propranolol for portal hypertension in cirrhosisAliment Pharmacol Ther201439655756824461301

- GluudLLKragABanding ligation versus beta-blockers for primary prevention in oesophageal varices in adults.Cochrane Database Syst Rev20128CD004544

- Garcia-PagánJCBoschJEndoscopic band ligation in the treatment of portal hypertensionNat Clin Pract Gastroenterol Hepatol200521152653516355158

- HigginsJPTGreenSCochrane Handbook for systematic reviews for interventionsCochrane Database Syst Rev2008 Available from: https://www.radioterapiaitalia.it/wp-content/uploads/2017/01/cochrane-handbook-for-systematic-reviews-of-interventions.pdfAccessed January 21, 2019

- HigginsJPThompsonSGDeeksJJAltmanDGMeasuring inconsistency in meta-analysesBMJ2003327741455756012958120

- ElnadryMHAbdel-AzizIMElshaffeeAMEndoscopic band ligation versus carvedilol for primary prevention of bleeding esophageal varices clinical.Biochemical and Doppler Ultrasonographic Evaluation2010 Available from: http://www.aamj.eg.net/journals/pdf/1267.pdfAccessed January 21, 2019

- MaharajSSeegobinKPerez-DownesJBajricBChangSReddyPSevere carvedilol toxicity without overdose – caution in cirrhosisClin Hypertens20172312529214053

- TiniakosDGPapatheodoridisGVSerum markers of hepatocyte apoptosis: current terminology and predictability in clinical practiceHepatology201051271771819918977

- ReibergerTUlbrichGFerlitschACarvedilol for primary prophylaxis of variceal bleeding in cirrhotic patients with haemodynamic non-response to propranololGut201362111634164123250049

- ShahHAAzamZRaufJCarvedilol vs. esophageal variceal band ligation in the primary prophylaxis of variceal hemorrhage: a multicentre randomized controlled trialJ Hepatol201460475776424291366

- Abd ElrahimAYFouadRKhairyMEfficacy of carvedilol versus propranolol versus variceal band ligation for primary prevention of variceal bleedingHepatol Int2018121758229185106

- AhmadMSamyEAal EmanAHosamDEvaluation of carvedilol in prevention of first attack of variceal hemorrhage in patients with liver cirrhosisAfro-Egyptian Journal of Infectious and Endemic Diseases2012228791

- StanleyAJDicksonSHayesPCMulticentre randomised controlled study comparing carvedilol with variceal band ligation in the prevention of variceal rebleedingJ Hepatol20146151014101924953021

- TripathiDFergusonJWKocharNRandomized controlled trial of carvedilol versus variceal band ligation for the prevention of the first variceal bleedHepatology200950382583319610055

- SchepkeMDrugsSMDrugs, ligation or both for the prevention of variceal rebleeding?Gut20095881045104619592688

- Garcia-PaganJCde GottardiABoschJReview article: the modern management of portal hypertension – primary and secondary prophylaxis of variceal bleeding in cirrhotic patientsAliment Pharm Ther2008282178186

- LiLYuCLiYEndoscopic band ligation versus pharmacological therapy for variceal bleeding in cirrhosis: a meta-analysisCan J Gastroenterol201125314715521499579

- FunakoshiNDunyYValatsJCMeta-analysis: beta-blockers versus banding ligation for primary prophylaxis of esophageal variceal bleedingAnn Hepatol201211336938322481457

- VorobioffJPicabeaEVillavicencioRAcute and chronic hemodynamic effects of propranolol in unselected cirrhotic patientsHepatology1987746486533610045

- RoloAPOliveiraPJMorenoAJPalmeiraCMChenodeoxycholate induction of mitochondrial permeability transition pore is associated with increased membrane fluidity and cytochrome c release: protective role of carvedilolMitochondrion20032430531116120330

- BakrisGLFonsecaVKatholiREMetabolic effects of carvedilol vs metoprolol in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus and hypertension: a randomized controlled trialJAMA2004292182227223615536109

- AkbasHOzdenMKankoMProtective antioxidant effects of carvedilol in a rat model of ischaemia-reperfusion injuryJ Int Med Res200533552853616222886

- SinhaRLockmanKAMallawaarachchiNRobertsonMPlevrisJNHayesPCCarvedilol use is associated with improved survival in patients with liver cirrhosis and ascitesJ Hepatol2017671404628213164