Abstract

Eye disease due to herpes simplex virus (HSV) is a leading cause of ocular morbidity and the number one infectious cause of unilateral corneal blindness in the developed parts of the globe. Recurrent keratitis can result in progressive corneal scarring, thinning, and vascularization. Antiviral agents employed against HSV have primarily been nucleoside analogs. Early generation drugs included idoxuridine, iododesoxycytidine, vidarabine, and trifluridine. While effective, they tended to have low bioavailability and measurable local cellular toxicity due to their nonselective mode of action. Acyclovir 0.3% ointment is a more selective agent, and had become a first-line topical drug for acute HSV keratitis in Europe and other places outside of the US. Ganciclovir 0.15% gel is the most recently approved topical treatment for herpes keratitis. Compared to acyclovir 0.3% ointment, ganciclovir 0.15% gel has been shown to be better tolerated and no less effective in several Phase II and III trials. Additionally, topical ganciclovir does not cause adverse systemic side effects and is therapeutic at lower concentrations. Based on safety, efficacy, and tolerability, ganciclovir 0.15% gel should now be considered a front-line topical drug in the treatment of dendritic herpes simplex epithelial keratitis. Topics of future investigation regarding other potential uses for ganciclovir gel may include the prophylaxis of recurrent HSV epithelial keratitis, treatment of other forms of ocular disease caused by herpesviruses and adenovirus, and ganciclovir gel as an adjunct to antitumor therapy.

Herpes simplex virus ocular infection

Eye disease due to herpes simplex virus (HSV) is a leading cause of ocular morbidity and the number one infectious cause of unilateral corneal blindness in the developed parts of the world.Citation1–Citation8 Herpes simplex type 1 (HSV-1) is the most common herpes virus implicated in ocular infections. Herpes simplex type 2 (HSV-2) can also infect ocular tissues, but in such instances is more commonly seen in the neonatal setting.Citation2

A recent survey revealed that nearly 60% of individuals in the US are seropositive for HSV-1, indicating that they had been exposed to the virus.Citation9 Polymerase chain reaction testing of trigeminal ganglia in cadavers detected a greater presence of HSV with increasing age, reaching almost 100% by the age of 60 years.Citation2 An estimated 400,000 to 500,000 individuals have experienced some form of ocular infection with HSV in the US.Citation1,Citation6,Citation10–Citation12 Incidence of HSV keratitis in the US and Europe ranges from 4.1 to 31.5 cases per 100,000 per year, of which 42% comprise new cases and 58% recurrent cases.Citation4,Citation5,Citation13–Citation15 In raw numbers, that represents some 48,000 to 59,000 episodes of ocular herpes diagnosed each year stateside, 20,000 to 24,000 of these being new primary cases.Citation3,Citation4,Citation10,Citation12,Citation14 Across the globe, roughly one million new or recurrent cases of herpes simplex epithelial keratitis occur annually.Citation16 Epithelial keratitis is the most prevalent form of ocular herpes simplex infection, comprising 50% to 80% of cases.Citation16

The herpesviruses comprise a family of DNA viruses, eight of which are known to cause human disease.Citation2,Citation3,Citation17 Herpesviruses have been implicated in numerous varied and, often, extremely serious diseases – several with ophthalmic manifestations. HSV-1, most commonly observed in the form of herpes labialis, is responsible for an estimated 98% of nonneonatal ocular infections.Citation2,Citation4,Citation18,Citation19 HSV-2 is the usual etiologic agent for genital and neonatal herpes infections; it can occasionally also infect ocular and orofacial structures through sexual transmission. The clinical appearance of keratitis from HSV-1 and HSV-2 is essentially the same.Citation1 Neonatal herpes simplex infection, which can involve HSV-1 as well as HSV-2, is most frequently transmitted through the birth canal.Citation2,Citation4 Eighty percent of infected neonates with no central nervous system involvement develop keratitis, and 10% manifest conjunctivitis.Citation7 Varicella-zoster virus is behind another consequential ocular infection - herpes zoster ophthalmicus. Epstein-Barr virus can cause acute mononucleosis and, along with it, a secondary keratitis. Cytomegalovirus (CMV) underlies a severe retinitis that can develop in immunoincompetent individuals, such as those with adult immune deficiency syndrome due to human immunodeficiency virus. The other human herpesviruses are: human herpesvirus 6, human herpesvirus 7, and human herpesvirus 8. The latter is associated with Kaposi’s sarcoma, lymphoma, and multicentric Castleman’s disease.Citation17,Citation20 The herpesviruses have in common an icosahedral coat and they reproduce by replicating double stranded DNA. Their virions invade living cells, establishing latency in the cell nuclei, where their linear genome is transformed into circularized episomes that are not integrated into the host DNA chromosome.Citation17,Citation21,Citation22 During the replication process, host cellular machinery is recruited to aid in the transcription and production of virally-encoded proteins (including virally-encoded factors, DNA-dependent DNA polymerase, and transcription factors) that ultimately effect DNA replication and virion assembly.Citation23

HSV-1 is typically transmitted through nonsexual contact in childhood.Citation1,Citation4 Primary ocular HSV infection may be undetectable or mild a majority of the time.Citation2 It is estimated that as low as 1% to 6% of initially infected individuals exhibit actual clinical signs and symptoms.Citation1,Citation2,Citation4 Following HSV exposure, there is an incubation period of 1 to 28 days.Citation10 Primary HSV-1 disease may then manifest clinically as a nonspecific upper-respiratory-tract prodrome.Citation24 A vesicular or ulcerative eruption develops over skin and mucus membranes innervated by the fifth cranial nerve such as the periorbital region, where it may present as blepharitis, acute follicular conjunctivitis, or epithelial keratitis.Citation4,Citation24–Citation28 In a Rochester, Minnesota study that followed, for as long as 33 years, 122 patients who were diagnosed for the first time with ocular HSV, initial infections were found to be predominantly corneal.Citation2,Citation28 By contrast, a Moorfields hospital study following 108 patients with ocular HSV for up to 15 years found that most primary infections were located in the conjunctivae and palpebral regions.Citation2,Citation29 After the primary infection, the herpes virus enters a nonreplicating latent stage. It remains dormant indefinitely, typically in the trigeminal nerve ganglion, until such a time that it may reactivate, and then recurs clinically.Citation1,Citation3,Citation7 The virus has been discovered in other spinal ganglia as well.Citation30 Additionally, there is some evidence to suggest that the cornea itself may represent yet another site where latent herpes virus may reside.Citation31,Citation32 Herpes simplex viral DNA has been detected in the cornea through polymerase chain reaction and other means. Some debate whether this may represent low-level active infection rather than true latency.Citation19 Regardless, current methods to detect infectious virus in tissue have limited sensitivity, and the validity of the corneal latency theory therefore has not been conclusively proven.Citation19,Citation33

HSV sometimes seems to reactivate in response to physical, hormonal, or emotional factors.Citation34,Citation35 Stress, ocular trauma, contact lens use, ultraviolet radiation, immune compromise, and hormonal changes have all been identified as possible triggers.Citation2–Citation4,Citation7,Citation10,Citation26,Citation36,Citation37 Conversely, the Herpes Eye Disease Study Group looked at several of these factors, such as psychological stress, systemic infection, sunlight exposure, menstrual period, contact lens wear, and eye injury, and found no statistically significant association between any of them and the reactivation of ocular herpes disease.Citation38 There may be additional external triggers for herpetic disease. For uncertain reasons, there is some predilection for ocular herpes to occur during the winter months.Citation2,Citation10 The incidence of HSV keratitis is increased up to six-fold after corneal transplant, when performed for nonherpetic conditions.Citation2,Citation39,Citation40 Although some cases could be explained by possible activation of previously-unrecognized latent host disease,Citation40 other occurrences after penetrating keratoplasty appear to be due to actual transmission of herpes virus from donor tissue to recipient.Citation31,Citation32 Corneal treatment with the excimer laser can predispose to recurrent herpes ocular disease, as well as stimulate viral shedding.Citation26,Citation41 Underlying local and systemic immunologic deficiency – such as the prior use of steroids and other immunosuppressives, atopic disease, malignancy, and human immunodeficiency virus infection – appears to promote the severity and frequency of infection.Citation2,Citation4 In summary, although the chain of events required to effect HSV reactivation have not been fully elucidated, they appear to be determined by a combination of host, virus, and environmental factors.

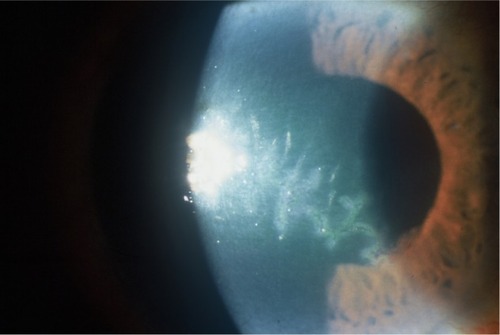

Recurrent herpes eye infection frequently presents as epithelial ulceration, which can be further described as dendritic or geographic in appearance (). The latter may be a more severe version of the former. In deeper layers of the cornea, HSV can cause stromal keratitis and endotheliitis. Uveitis can sometimes accompany keratitis, or may occur independently. Patients with stromal disease and uveitis almost always have concomitant epithelial involvement, or have had a history of antecedent HSV epithelial keratitis.Citation10 Additional ocular manifestations include blepharitis, canaliculitis, retinitis, and optic neuritis.Citation7

Thirty-two percent of those who have an episode of primary HSV infection will go on to experience recurrences within 15 years.Citation29 Previous episodes of herpetic eye disease, especially if stromal and multiple, predispose to subsequent recurrences.Citation42 Dendritic keratitis was the most common form of recurrent disease in the previously cited Rochester, Minnesota study.Citation28 In the Moorfields Hospital study, however, most recurrences were either conjunctival or palpebral, with only 9% exhibiting dendritic ulcers.Citation29 Recurrences tend to present in the same general location as prior ocular HSV infection.Citation28 Therefore, the differences in the location of recurrent disease for these two studies are probably directly related to differences in the location of the primary infections. With respect to keratitis specifically, prior ulcerative keratitis does not necessarily presage subsequent epithelial recurrences. However, an occurrence of stromal keratitis increases by tenfold the risk of future stromal episodes.Citation42

Only half of herpetic corneal ulcers will heal spontaneously within 2 weeks.Citation16 Untreated, or with inappropriate steroid administration, herpetic epithelial dendrites are more likely to progress to larger geographic and ameboid lesions.Citation1,Citation14 Children appear susceptible to developing more severe HSV keratitis, including geographic ulcers.Citation2 Repeated occurrences of ulcerative disease as well as chronic stromal keratitis can result in progressive corneal scarring, thinning, and vascularization.Citation3,Citation14 Ultimately, visual acuity can be affected to the point where a patient is in need of corneal transplant. Starting at 15,000 per year in 1981, the number of penetrating keratoplasties performed in the United States reached a high of 36,000 per year by 1990.Citation43,Citation44 In 2004, penetrating keratoplasties in the US had dipped somewhat to 32,106, alongside 51,544 total grafts worldwide.Citation44 According to several reports covering the past 30 years or so in the US and various other developed countries, somewhere around 5% (0.6% to 10%) of corneal transplants are for scarring due to HSV.Citation2,Citation43,Citation45–Citation53 HSV keratitis, however, can go on to recur in the graft itself, resulting in scarring, graft failure, and rejection.Citation7,Citation8 The presence of unrecognized latent HSV in recipient corneas may elevate the risk of primary graft failure as well as late endothelial failure.Citation54,Citation55 Evidence for HSV-1 within donor tissue has also been found, and felt to be a potential cause for primary graft failure.Citation56 It is clear that the ability to treat and prevent recurrences of HSV keratitis is an important public health issue as it relates to vision, conservation of valuable limited resources (such as transplant tissue), and healthcare expenses. Effective therapy is highly desirable to lessen the morbidity of the infection, and in so doing, mitigating the corneal and visual consequences.

Antiviral therapy

The antiviral agents employed against HSV have primarily been nucleoside analogs. They function by competitive inhibition, becoming incorporated into viral DNA within infected cells. Viral DNA synthesis in this manner is interrupted by the irreversible binding of viral DNA polymerase.Citation7,Citation57 Early generation drugs included idoxuridine, iododesoxycytidine, vidarabine, and trifluridine. They tended to have low bioavailability and measurable local toxicity.Citation3,Citation14,Citation58,Citation59 Idoxuridine, an analog of the pyrimidine thymidine, was the first effective agent, introduced in 1962. Its efficacy was limited by ocular surface toxicity and poor hydrosolubility.Citation60 It eventually fell out of use in the early 1990s in favor of more effective and better-tolerated topical medications.Citation5 Vidarabine, a purine analog, exhibits somewhat fewer side effects than idoxuridine, but still not-insignificant local toxicity.Citation3,Citation7,Citation59 Formulated as an ointment, vidarabine is poorly soluble like idoxuridine, limiting effective corneal penetration.Citation7,Citation8,Citation60 At least in part for these reasons, vidarabine is considered less preferable than trifluridine and acyclovir, and has generally fallen out of use.Citation61 Trifluridine, a synthetic pyrimidine nucleoside, was approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) as a 1% solution for treatment of HSV keratitis in 1980.Citation5 It is administered every 2 hours while awake, up to nine times a day. It has become the most widely used topical antiviral agent for treatment of HSV keratitis in the United States.Citation3,Citation14 Toxic local side effects, however, have been described as particularly severe.Citation3,Citation4

The aforementioned topical agents have proven to be effective in reducing the duration of infection, as well as decreasing scarring and other pathologic consequences of ulcerative HSV keratitis. At the same time, the drugs are also generally nonselective in their activity against DNA synthesis. Although they shut down viral processes, they will interrupt cellular function just as readily by being incorporated into human cellular DNA.Citation3 In so doing, they inhibit DNA replication of both normal and viral-infected cells.Citation4,Citation5 Consequently, these agents have tended to exhibit cellular toxicity. Prolonged use has manifested itself in adverse side effects, mostly involving ocular surface toxicity. These effects include: epithelial keratitis, ulceration, and dysplasia; delayed wound healing; follicular and cicatricial conjunctivitis; and punctal and canalicular stenosis.Citation5,Citation7,Citation8,Citation14,Citation60,Citation62–Citation64

Acyclovir is another purine nucleoside analog, but with selective inhibitory activity against HSV DNA polymerase.Citation7,Citation14,Citation59 It is able to inhibit viral DNA synthesis without concomitantly interrupting cellular processes of uninfected host cells.Citation1 In Europe, acyclovir is available as a 3% ointment. It has been demonstrated to be effective against HSV ulcerative keratitis, reducing healing time and adverse visual consequences. Local toxicity is less than that of the nonselective agents.Citation14,Citation60 Acyclovir is poorly soluble in water, however, requiring formulation in a polyethylene glycol base. The ointment can cause some discomfort as well as blurred vision, which in turn can affect patient compliance.Citation1,Citation3,Citation6,Citation14,Citation65 Nevertheless, acyclovir 3% ointment came to be the first-line topical treatment for HSV epithelial keratitis in Europe and other countries outside of the US. Oral acyclovir, as well as other oral agents such as valacyclovir, appears to have similar efficacy to that of the topical form.Citation15,Citation16,Citation65–Citation69 The few studies that compared oral plus topical antiviral therapy to topical treatment alone found the combined regimen to be as efficacious as, but not more so, than topical antiviral therapy only.Citation16,Citation68,Citation70 Oral acyclovir has been shown to be useful for prevention of recurrent HSV eye disease in its various manifestations.Citation71–Citation74 Once discontinued, however, reactivation of HSV eye disease returns to pretreatment rates, as the latent form of the virus is not eradicated by this virustatic medication.Citation57,Citation75

Ganciclovir

Metabolism and antiviral action

Ganciclovir, like acyclovir, is a synthetic purine nucleoside, and an analog of guanosine. Its chemical structure is 9-[[2-hydroxy-1-(hydroxymethyl)ethoxy]methyl] guanine (CAS number 82410-32-0), with empirical formula C9H13N5O4 and molecular weight 255.23.Citation2–Citation4,Citation7,Citation76 Ganciclovir is phosphorylated by viral thymidine kinases of the herpesvirus family and other viruses, and by protein kinase of CMV, into ganciclovir monophosphate.Citation1 Within virus-infected cells, both viral and cellular thymidine kinases catalyze further phosphorylation of ganciclovir monophosphate into ganciclovir triphosphate, the active metabolite.Citation1,Citation3–Citation5 Ganciclovir triphosphate accumulates in virus-infected host cells, interfering with viral replication in two ways: 1) it is directly incorporated into viral strand primer DNA, inducing DNA single- and double-strand breaks, and resulting in viral DNA chain termination;Citation14,Citation77 and 2) being a derivative of 2′-deoxyguanosine, it competes with deoxyguanosine triphosphate for binding to viral DNA-polymerase, interrupting new viral DNA synthesis.Citation1,Citation3,Citation14,Citation76 Ganciclovir’s potent genotoxic effects are irreversible.Citation78 HSV-infected cells become rapidly apoptotic, resulting in cell death.Citation77,Citation79 Because ganciclovir is not recognized as a substrate by human thymidine kinase within healthy human cells, the active metabolite does not build up in uninfected cells.Citation5 Consequently, while strongly inhibiting viral replication in cells infected with HSV, it does not damage DNA or interfere with DNA polymerization in healthy cells.Citation3,Citation57,Citation80 The effects of ganciclovir are thus limited to HSV-infected cells, resulting in less potential host toxicity.Citation5

Indications

Systemic ganciclovir is administered in intravenous, oral, and vitreous implant forms. It is FDA-approved for treatment of CMV retinitis in immunocompromised individuals (including those with acquired immunodeficiency syndrome), and for prevention of CMV disease in bone marrow and solid organ transplant recipients at risk for CMV disease.Citation4,Citation7,Citation8 Off-label uses include prevention of recurrent CMV retinitis and treatment of CMV pneumonitis, CMV neurological disease, progressive outer retinal necrosis caused by varicella-zoster virus, and certain human herpesvirus 8 diseases.Citation20 Ganciclovir, both systemic and topical, has also been used with some success in treatment of CMV endothelitis.Citation81–Citation84 It is considered to be a first-line choice of therapy for these sight- and life-threatening CMV infections.Citation85 Ganciclovir has a broad spectrum of activity against a variety of viruses, including all human herpesviruses (including HSV-1, HSV-2, varicella-zoster virus, Epstein-Barr virus, CMV, and human herpesvirus 6) and adenovirus.Citation1,Citation3–Citation5,Citation14,Citation65 The drug appears to have equal or greater potency against the herpesviruses, with the exception of CMV, than does acyclovir.Citation3,Citation78,Citation85,Citation86 CMV does not have an exact thymidine kinase gene homologue; instead, the CMV UL97 gene, with putative thymidine kinase activity, phosphorylates ganciclovir.Citation87 Although it slows replication of CMV DNA, ganciclovir (unlike acyclovir) is not an absolute chain terminator in this case, and small subgenomic fragments of CMV DNA continue to be synthesized.Citation88 Nonetheless, its superiority to acyclovir in inhibiting CMV replication lies in its tenfold greater intracellular concentration.Citation3,Citation89 As a virustatic agent, ganciclovir does not eradicate virus in the latent phase, and so maintenance therapy may be required to prevent recurrences.Citation85 When administered systemically, it exhibits hematologic toxicity, although effects are usually reversible.Citation3,Citation7,Citation8,Citation85 Systemic ganciclovir has been associated with granulocytopenia, thrombocytopenia, anemia, azoospermia, and a rise in serum creatinine.Citation89

While not available commercially, oral ganciclovir was shown in one study to be efficacious in relieving symptoms and shortening the clinical course of herpes stromal keratitis and endotheliitis. In a single-blind prospective trial carried out from 2008 to 2009 at a Fudan University hospital, Wang et al compared two therapeutic regimens involving ganciclovir for the symptomatic relief and cure of herpes stromal keratitis and corneal endotheliitis.Citation86 They demonstrated that oral ganciclovir, when added to a regimen of ganciclovir 0.15% ophthalmic gel and fluorometholone eye drops, was found to be superior to treatment consisting of only ganciclovir gel and fluorometholone. Nevertheless, since ganciclovir is poorly absorbed in the gastrointestinal tract, its potential use as an oral agent in the future remains unclear.Citation90

Dosage formulations

Ganciclovir is now approved as a topical antiviral agent for treatment of acute herpes simplex epithelial dendritic ulcerative keratitis, in the form of a 0.15% aqueous gel. It is marketed in Europe under the trade name Virgan® (Spectrum Théa Pharmaceuticals, Macclesfield, UK) and has been available outside of the United States since 1996. Ganciclovir gel 0.15% was more recently approved by the FDA in the United States, since September 2009, as Zirgan® (Bausch and Lomb Incorporated, Rochester, NY, USA). With a pH of 7.4, each gram of the gel contains 1.5 mg of active ganciclovir in a hydrophilic polymer base, carbomer 974P.Citation88 Benzalkonium chloride 0.0075% is used as a preservative. Dosing schedules for both Zirgan® and Virgan® are for use in the affected eye, one drop five times per day (about every 3 hours while awake) until the corneal ulcer heals, then one drop three times a day for 7 additional days. The medication appears most effective when used early in the course of the infection.Citation78 Patients are warned not to wear contact lenses while using ganciclovir gel for treatment of active herpes keratitis due to the potential link between herpes keratitis recurrence and contact lens use.Citation37,Citation76 Several clinical trials have shown ganciclovir 0.15% ophthalmic gel to be both safe and effective; the topical formulation is well tolerated, nontoxic to the ocular surface, and does not cause adverse systemic side effects.Citation7,Citation8,Citation14,Citation65,Citation92,Citation93

Ocular pharmacokinetics

Both acyclovir and ganciclovir topical forms demonstrate effective penetration in and through the cornea to achieve therapeutic levels in deeper structures, including the aqueous humor.Citation7,Citation8,Citation59 Its hydrophilic base allows ganciclovir to be solubilized as an aqueous gel. This, in turn, enhances drug resorption, permitting equivalent therapeutic effects at far lower concentrations than that of acyclovir 3% ointment.Citation59 The effective median dose of ganciclovir in vitro against clinical ocular isolates of herpes simplex virus is 0.23 μg/mL.Citation14,Citation65 A single drop of ganciclovir gel, instilled on the ocular surface, can produce tissue concentrations (Cmax [maximal concentration]) in the cornea (17 μg/g), conjunctiva (160 μg/g), aqueous humor (1 μg/g), and iris and ciliary body (4 μg/g), which surpass the effective concentrations for HSV-1 and HSV-2 for over 4 hours.Citation91 This capacity to concentrate in ocular tissues and fluids could be related to ongoing drug absorption over time, as the gel formulation permits extended drug contact on the ocular surface.Citation5,Citation59,Citation94 Indeed, ganciclovir gel has often been described as “galenic”, after the ancient physician Galen, implying a medication designed with maximal absorption properties in mind.Citation14,Citation59 Ganciclovir is a relatively small-sized molecule with high lipophilicity and high cellular affinity.Citation59 Its lipophilic nature causes ganciclovir to be poorly soluble in water; this is likely the reason that, for topical use, it was not formulated as an aqueous solution.Citation59 At the same time, however, increased lipophilicity has been shown to enhance permeability through the corneal epithelium by improving absorption into the lipoidal corneal epithelial cells.Citation3,Citation95 The presence of an epithelial defect enhances corneal absorption even more by eliminating one of the primary barriers to absorption (ie, the epithelium).Citation59,Citation96,Citation97 Hence, one would expect better passage of topical ganciclovir through the cornea in earlier stages of an infection when the ulceration is presumably at its largest. Topical ganciclovir appears to primarily pass through the cornea by means of passive diffusion.Citation98 This method is by no means inefficient as measurable levels of ganciclovir can be found within the anterior chamber of rabbit eyes within 5 minutes of administration.Citation97

Preclinical studies

Preclinical studies have examined topical ganciclovir’s effects on animal models, particularly rabbit corneas, and demonstrated efficacy in decreasing the severity of herpes keratitis.Citation59,Citation96,Citation99 Castela et al examined the effects of ganciclovir gel 0.2%, 0.0125%, and 0.05% in comparison with acyclovir 3% ointment in a rabbit model of HSV keratitis.Citation4,Citation59 Corneal ulcer size, clouding, and vascularization were all significantly reduced in all drug-treated groups compared with placebo (P<0.05). Acyclovir 3% ointment was not significantly different than ganciclovir 0.05% gel in clinical efficacy, but was significantly better than the 0.2% and 0.0125% gels. HSV-1 was cultured from pooled tear samples to determine duration of infectivity. Viral shedding was eliminated after 12 days with the 0.2% and 0.05% ganciclovir gels – faster than the 14 days required using placebo, but not as rapidly as for the group receiving acyclovir ointment (10 days). The differences in viral eradication between the ganciclovir 0.05% gel and the acyclovir 3% ointment groups, however, were not statistically significant. Corneal penetration was good: the mean corneal concentrations were high with the 0.2%, 0.05%, and 0.0125% gels being nine, 1.5, and three times higher, respectively, than the effective median dose (0.20–32 μg/mL) of the in vitro HSV strain. Castela et al discovered, in their study, mild to very high levels of ganciclovir in several cellular tissues: cornea and chorio–retina for all three gel concentrations, and iris for all but the 0.0125% formulation.Citation59 By contrast, the mean concentrations of ganciclovir in ophthalmic fluids and plasma were generally very low. This difference might be explained by ganciclovir’s comparatively poor water solubility. There was, nevertheless, still a detectable presence of therapeutic levels of ganciclovir in the aqueous humor 4 hours after the last topical administration of the 0.2% gel. The authors postulated that this could be related to slow diffusion of the drug into the aqueous humor from the cornea. No ocular or systemic toxicity was expected or noted in the study.Citation59

There is some degree of dose–response relationship in this study. Rabbits exhibited a faster ulcer healing time with ganciclovir 0.05% than with the other two concentrations. Only the 0.05% gel was equivalent to acyclovir 3% gel in efficacy. The 0.2% gel achieved the higher drug levels in cornea, iris, and aqueous humor compared to the less concentrated formulations. Paradoxically, the 0.0125% gel achieved somewhat higher corneal concentrations than the 0.05% gel; however, this did not seem to translate into faster clinical healing or duration of viral shedding.Citation59

Trousdale et al demonstrated the clinical efficacy of ganciclovir ointment prepared in different concentrations.Citation96 They treated experimental HSV-1 keratitis in rabbit eyes with ganciclovir 1%, ganciclovir 0.1%, acyclovir 3%, idoxuridine 1%, and placebo. All antiviral groups were superior to placebo; the two concentrations of ganciclovir showed no difference and were, along with acyclovir, superior to idoxuridine. In another animal investigation, Shiota et al found that ganciclovir 0.3%, prepared as an ointment, was more effective than acyclovir 3% and idoxuridine 0.5% ointments after 4 days of therapeutic use against herpetic ulcers in rabbit eyes.Citation100 The results of these different preclinical studies suggested that the optimal concentration for topical ganciclovir was likely to be greater than 0.0125% but less than 1%.

Clinical studies

Phase I studies

During Phase I investigations, ganciclovir gel 0.15% was administered to healthy human volunteers. In one randomized double-masked study, ten volunteers received ganciclovir gel 0.15% in one eye and its vehicle gel in the other eye five times per day for 7 days.Citation3,Citation4,Citation94,Citation101 Eyes were examined before, during, and after the treatment period; examination findings were unchanged between visits. The gels were generally well tolerated, producing no side effects deemed to be clinically significant by either subjects or investigators.Citation4,Citation94 Blurred vision, however, was noted by eighty percent of the participants after topical administration of the gels.Citation94 In a second masked trial, six male subjects were dosed with ganciclovir gel 0.15% in each eye every 3 hours over a 12 hour study period, totalling four instillations.Citation3,Citation4,Citation94,Citation102 This represented about 0.04% and 0.1%, respectively, of the typical daily oral and intravenous doses of ganciclovir, assuming full systemic absorption of the gel.Citation3 Tear samples were collected using Schirmer’s strips, and their ganciclovir concentrations assayed. Measurements were taken initially to obtain control levels, and then 2 hours, 45 minutes following each instillation of ganciclovir gel. Mean tear ganciclovir levels among study participants varied from 0.92 to 6.86 μg/mL, exceeding the mean effective concentration of HSV-1 by at least fivefold.Citation4,Citation94 Systemic levels of ganciclovir (11.5±3.7 ng/mL) were negligible.Citation3,Citation4,Citation101,Citation102 Apart from irritation from the paper strips, patients did not experience any additional discomfort from the topical medication.Citation4,Citation102

Phase II and III studies

There have been four key multinational multicenter controlled randomized single-masked open-label studies – three Phase IIb and one Phase III – comparing ganciclovir 0.15% gel to acyclovir 3% ointment, which is considered the gold standard internationally for topical treatment of HSV epithelial keratitis.Citation3,Citation5,Citation14,Citation65,Citation92,Citation93 Patients with herpetic ulcers, designated as dendritic or geographic, with no antiviral therapy in the previous 14 days, were eligible for inclusion; those with severe stromal disease, keratouveitis, previous keratoplasty, and immune deficiency were excluded. Phase II subjects were ≥2 years of age, while Phase III participants were age 18 and above.Citation1 Ganciclovir gel was demonstrated to be, at a minimum, as effective as acyclovir ointment, actually healing ulcers more rapidly and at a higher rate. The 0.15% gel also proved to have better tolerability, causing fewer treatment-related adverse side effects than the 3% ointment.Citation14,Citation103

Phase II studies examined the optimal concentration and dosing schedule for subjects ≥2 years old with active herpes epithelial keratitis, considering efficacy as well as adverse effects.Citation1 Topical ganciclovir gel 0.15% was compared against topical acyclovir ointment 3%. The clinical trials lasted 15 to 25 months and enrolled 213 total patients, with all studies being completed by May 1992.Citation3 Study one was conducted in Africa, involving 67 eyes of 66 patients, and study two was from Europe, with 37 participants from four study centers in France, Switzerland, and England.Citation3,Citation14,Citation92 A third Phase II study (study three) from Pakistan compared ganciclovir and acyclovir on 36 and 38 subjects, respectively.Citation5,Citation93 For studies one and three, there was also a ganciclovir 0.05% treatment arm.Citation5,Citation14,Citation93 Study four was the largest of the clinical studies, involving 164 subjects ≥18 years of age with herpes keratitis from 28 study centers in France, England, Ireland, Mali, Tunisia, and Madagascar.Citation1,Citation65 Patients were followed for 2 years between September 1992 and September 1994 in this Phase III trial.Citation57,Citation65,Citation104 The four studies are summarized in .

Table 1 Phase II and III clinical studies

In a retrospective pooled analysis of the three Phase IIb clinical trials, ganciclovir 0.15% gel was found to be noninferior to acyclovir 3% ointment in healing dendritic HSV ulcers.Citation1,Citation11 Median healing time for ulcers was 6–10 days.Citation1 Seventy-two percent of patients who were administered ganciclovir gel demonstrated clinical resolution at day 7 in comparison to 69% of those treated with acyclovir ointment (difference 2.5%; 95% confidence interval −15.6% to 20.9% [numbers derived from pooled data]).Citation11 In addition, 81% of dendritic ulcers resolved at day 10 and 89% at day 14. Median time to recovery in the three Phase II studies (pooled) was 6–7 days for ganciclovir gel and 7–8 days for acyclovir ointment. In the per protocol population of study two, the median time to healing for the ganciclovir group (6 days) was somewhat less than, but not significantly different from, the median healing time for the acyclovir group (7 days) (P=0.056).Citation4,Citation92 Recovery rates at 14 days in the same cohort were higher for topical ganciclovir (83.3%) than for acyclovir ointment (70.6%), but again without achieving statistical significance.Citation4,Citation14,Citation92 Sahin and Hamrah have additionally pooled the data from the three Phase II studies, looking specifically at the intent-to-treat study participants. The authors calculated a statistically significant difference in proportion of ulcers resolved at trial endpoint after ganciclovir gel treatment (85%) compared to treatment with acyclovir ointment (71%) (P=0.04).Citation3,Citation4

The Phase III multicenter randomized prospective study compared ganciclovir 0.15% gel and acyclovir 3% ointment for the treatment of herpes simplex epithelial keratitis, both dendritic and geographic.Citation65 Dendritic corneal ulcerations were of less than 7 days’ duration. Patients were randomized to receive ganciclovir gel or acyclovir ointment, with each drug being administered five times per day until healing of the ulcer, followed by three times daily for an additional 3 days. The two topical antiviral medications demonstrated comparable efficacy with no significant adverse effects. Following 7 days of treatment in the Phase III trial, 77% of patients on ganciclovir gel achieved clinical resolution of dendritic ulcers, versus 72% of those taking acyclovir 3% ointment (difference 5.8%; 95% confidence interval -9.6% to 18.3%); after 14 days, healing rates increased to 86% and 89%, respectively.Citation1,Citation5,Citation11,Citation76 These differences in healing time between the two groups were not statistically significant. Overall recovery rate over the entire duration of the Phase III treatment trial was 89% for recipients of ganciclovir gel and 91% for those receiving acyclovir ointment.Citation1,Citation5,Citation65 Median time to recovery from dendritic ulcers was 7 days for both the ganciclovir gel and acyclovir ointment treatment groups, as well as for geographic ulcers treated with acyclovir. Although median healing time was 9 days for geographic ulcers treated with ganciclovir gel, there were overall too few patients with geographic ulcers to derive meaningful statistical analysis.Citation4 As a result, since ganciclovir gel could not be demonstrated with statistical certainty to be noninferior to acyclovir ointment for treatment of geographic herpetic ulcers, ganciclovir 0.15% gel has not been approved in the US for this indication.Citation1 For the treatment of dendritic ulcers, however, ganciclovir 0.15% gel was established to be noninferior to acyclovir 3% ointment. When data is further pooled from all four major studies, including the Phase III trial, ganciclovir 0.15% gel continues to prove at least as effective as acyclovir 3% ointment in the treatment of herpes simplex dendritic epithelial keratitis.Citation1,Citation3,Citation4

The Phase II and III studies were not originally designed to ascertain noninferiority; noninferiority and comparable efficacy were confirmed through subsequent retrospective analysis.Citation1,Citation57 The trials initially held time-to-healing as the primary endpoint, and reported on efficacy data for day 14 of treatment. Treatment continued for a maximum period of 21 days for dendritic ulcers, and 35 days for geographic ones. For FDA approval, however, the primary endpoint needed to be redefined as the proportion of patients exhibiting clinical healing by day 7.Citation1,Citation57 The differences in median healing time for dendritic ulcers were not statistically significant for the different topical treatments in any of the four major studies.Citation1,Citation57

Investigators kept track of relapses occurring by day 14. Relapses developed in 0%–4% of ganciclovir-treated patients in the four clinical studies, and in 0%–14% of patients who received acyclovir. This actually amounted to only zero to two patients who relapsed for either drug in any one of the individual studies. Because of this small number of actual relapses, the percentage differences were not statistically significant.Citation1,Citation4,Citation5,Citation14,Citation57

Tolerability and adverse effects

The most common adverse and toxic side effects, as determined from pooled data from all four major studies, were blurred vision (ganciclovir 57.8%, acyclovir 71.3%), eye irritation (ganciclovir 25.6%, acyclovir 46.2%), punctate keratitis (ganciclovir 8.8%, acyclovir 16%), and conjunctival hyperemia (ganciclovir 5.6%, acyclovir 5%).Citation5 Bausch and Lomb Incorporated, in their full prescribing information for Zirgan® 0.15% ophthalmic gel, reported similar common side effects, with just slightly different percentages: blurred vision (60%), eye irritation (20%), punctate keratitis (5%), and conjunctival hyperemia (5%).Citation76 Ganciclovir 0.15% gel was generally better tolerated than acyclovir 3% ointment, virtually across the board, except for conjunctival hyperemia. There were fewer complaints of blurred vision, and discomfort such as burning and stinging in the ganciclovir group than in the acyclovir group.Citation4 Systemic absorption was low, and there were no adverse hematologic effects.Citation14 No adverse events were categorized as serious.Citation1,Citation65

Blurred vision and irritation

Eight out of the 10 study subjects in the first Phase I investigation reported blurred vision after ganciclovir gel adminisstration.Citation94 In each of the four subsequent key clinical studies, fewer patients reported blurred vision or eye irritation from ganciclovir gel than from acyclovir ointment.Citation3,Citation5 In Phase II, study two, the proportion of patients experiencing blurred vision after 1 week of therapy with ganciclovir gel (58%) was nearly one-third less than the proportion of patients with blurring after acyclovir ointment (89%); when it occurred, blurred vision also tended to last longer (>5 minutes) with acyclovir ointment than with ganciclovir gel.Citation3,Citation14,Citation57 At the same time, incidence of burning or stinging was nearly reduced threefold in ganciclovir (17%) versus acyclovir (50%).Citation14,Citation57 The Phase III trial, study four, found incidence of visual disturbances to be significantly less with ganciclovir gel than with acyclovir ointment on day 7 (P<0.05).Citation57,Citation65,Citation104 Furthermore there were significantly fewer complaints of stinging, tingling, and burning among ganciclovir recipients compared to those who received acyclovir ointment (P<0.05).Citation1,Citation3,Citation57 Hoh et al from England, Ireland, and France, in their portion of the Phase III report, indicated that 83.2% of subjects taking ganciclovir gel and 86.8% of those on acyclovir ointment noted blurred vision, ranging from mild to severe.Citation65 The visual disturbances lasted longer after topical instillation of acyclovir than ganciclovir, persisting an average of 32.9 and 22 minutes, respectively. The tonicity and pH of ganciclovir 0.15% gel are physiologic, a factor that likely plays at least a part in its overall tolerability.Citation59 Another aspect is its aqueous formulation, which appears for most patients to be preferable to, and more comfortable to administer than, an ointment-based medication.Citation3,Citation7,Citation8,Citation14,Citation57

Surface toxicity

In study one, a slightly higher percentage of patients on ganciclovir (13%) than on acyclovir (9%) exhibited toxic superficial punctate keratopathy (SPK) by day 14.Citation5,Citation14 Conversely in study four, toxic SPK was twice as prevalent in the acyclovir 3% ointment group than in the ganciclovir 0.15% gel group (P=0.03 at day 10) during treatment of dendritic ulcers.Citation65 No punctate keratitis was seen at all among the 13 patients with geographic ulcers who were placed on ganciclovir 0.15% gel during the fourth major clinical trial; by contrast, in the same trial, 15%–43% of 13 geographic ulcer patients exhibited SPK at various stages of follow-up during their treatment with acyclovir 3% ointment.Citation3,Citation5,Citation57,Citation65,Citation104 Punctate keratitis also remained nearly twice as prevalent among patients administered topical acyclovir compared to topical ganciclovir when data from all of the four pivotal studies were pooled.Citation5 Ching et al reviewed 88 trials of topical antiviral medications and found that 40 of them had data about adverse reactions. The median percentage of eyes exhibiting superficial punctate keratopathy for the following specific antivirals was: acyclovir, 10%; ganciclovir, 4%; trifluridine, 4%; and brivudine, 0%.Citation16

As with all topical drugs, use of ganciclovir gel conceivably carries a risk of local hypersensitivity reactions. Dermatological side effects have been noted with other antivirals; however, contact hypersensitivity of the skin or conjunctiva was not observed in any of the clinical studies of ganciclovir gel.Citation14,Citation16,Citation65,Citation90,Citation92,Citation93,Citation105 Only one case study reports an occurrence of generalized cutaneous rash and splinter hemorrhages, and that was from systemic ganciclovir use.Citation106

Subjective tolerability

In studies one, two, and four, both patients and investigators were asked to subjectively rate the local tolerability of administered antiviral medications.Citation3,Citation14,Citation65,Citation92 Seventy-five point four percent of subjects rated the tolerability of ganciclovir 0.15% gel as excellent, compared to 40.4% of those who received acyclovir 3% ointment. Investigators similarly rated ganciclovir 0.15% gel as having excellent tolerability more frequently than for acyclovir 3% gel: 81.8% versus 44.7%, respectively. The difference in patient ratings in study two, as well as both patient and investigator ratings in study four, were statistically significant (P<0.001).Citation5,Citation57,Citation65,Citation104 Based on these results, the major advantage of ganciclovir gel over acyclovir ointment appears to be its tolerability, with less blurred vision and ocular irritation. Patient withdrawals due to disease exacerbation, poor tolerance, or other complications were fewer among those given ganciclovir (11.2%) than those treated with acyclovir ointment (19.7%) (pooled data for the four major studies).Citation4,Citation5

Ganciclovir compared to other antivirals

Various topical antiviral agents have generally demonstrated similar efficacy in the treatment of HSV epithelial keratitis. In 52 studies reviewed for the Preferred Practice Pattern® monograph published by the American Academy of Ophthalmology, trifluridine, acyclovir, brivudine, and ganciclovir were all similar, helping 90% of total corneas to heal within 2 weeks.Citation16 Wilhelmus conducted a review of literature from 1950 to 2010 encompassing 106 comparative trials and 5,872 patients.Citation61 Acyclovir, ganciclovir, vidarabine, brivudine, and trifluridine, on meta-analysis, all appeared superior to idoxuridine; additionally, trifluridine and acyclovir, while themselves equally effective, were both superior to vidarabine; brivudine and ganciclovir were at least as effective as acyclovir and trifluridine.Citation61

Adverse local reactions have been frequently observed to varying degrees after use of any and all of the topical antiviral eyedrops. These side effects include stinging upon instillation, allergic blepharoconjunctivitis, superficial keratopathy, and toxoallergic follicular conjunctivitis.Citation16 Oral acyclovir appears to be equally effective as the topical antivirals, but without the local side effects.Citation61

Topical trifluridine 1% has been hitherto the only topical antiviral agent commercially available for use against dendritic herpes simplex keratitis in the United States. Despite this fact, ganciclovir gel 0.15% has not been directly compared to trifluridine 1% in human studies. At the 2008 Annual Meeting of the Association for Research in Vision and Ophthalmology, Varnell and Kaufman reported on their study comparing ganciclovir ophthalmic gel 0.15% and trifluridine ophthalmic solution 1% in the treatment of experimental herpetic keratitis.Citation107 Rabbits were infected with McRae strain of HSV-1 and then treated with one of the two antivirals. The two drugs demonstrated clinical equivalency. In a separate masked trial focused on toxicity, uninfected rabbits with intact corneas and corneal epithelial defects were administered either topical trifluridine drops or ganciclovir gel.Citation108 Those with intact epithelium or small epithelial defects did not demonstrate toxicity after 14 days’ treatment. However, rabbits with total epithelial defects exhibited more conjunctival inflammation and corneal edema after 20 days of treatment with trifluridine drops than after ganciclovir gel (P<0.0001).Citation5,Citation108 This finding suggests that topical ganciclovir may be slightly less toxic than trifluridine, especially during more extended therapy.Citation103 Gordon et al looked at the antiherpetic effects of ganciclovir, the cyclic ganciclovir derivative 2′-nor-cGMP, and trifluridine in BALB/c mice inoculated with HSV-1.Citation109 The two forms of ganciclovir were found to be significantly more effective than trifluridine in reducing ocular HSV titers and improving epithelial keratitis in the mice (P=0.0001). With respect to reducing stromal keratitis, all three drugs were clinically equivalent, and also significantly more effective than balanced salt solution. It is important to note that no trials have been performed to directly compare these effects in a clinical setting.

Antiviral resistance

Most HSV isolates have been found to be sensitive to acyclovir and ganciclovir while exhibiting more variable sensitivity to idoxuridine and vidarabine.Citation110 As has been observed with antimicrobials, the effectiveness of antiviral agents may be limited by emerging pathogen resistance.Citation14,Citation111–Citation113 Resistance to acyclovir has already been observed.Citation114 Since it has a similar structure and mechanism of action to acyclovir, ganciclovir might be expected to face viral cross-resistance.Citation6 HSV resistance to nucleoside analogues such as ganciclovir, however, is not extremely common, with a relatively low 0.1%–0.7% prevalence among immunocompetent individuals.Citation1,Citation5,Citation115 It turns out that viruses that become resistant to acyclovir may remain sensitive to ganciclovir.Citation78 The molecular mechanisms that underlie ganciclovir activity – namely, the appropriation of the virus’ own thymidine kinase activity – hinder the ready development of viral resistance.Citation5 Nevertheless, resistance may be conferred by mutations in viral thymidine kinase that render the virus unable to phosphorylate the nucleoside analog drugs.Citation78,Citation89,Citation116 Hlinomazová et al found 14% of patients with polymerase chain reaction-proven HSV-1 keratitis and keratouveitis to be clinically acyclovir-resistant. Patients not responding to acyclovir were all subsequently treated successfully with topical ganciclovir gel 0.15%.Citation6 Duan et al examined 173 isolates from patients with HSV-1 keratitis. Eleven isolates (6.4%) were acyclovir resistant in vitro, and nine of the eleven were refractory to acyclovir treatment. Five of eleven were additionally cross resistant to ganciclovir.Citation116 Drug-resistant herpes simplex viruses that enter latency may retain resistance after subsequent reactivation.Citation117 Host immunologic deficiency appears to promote HSV drug-resistance: 4% to 7% of HSV isolates taken from immunocompromised patients have been found to be resistant to nucleoside analogs such as acyclovir.Citation1,Citation115,Citation118 HSV cross-resistance to acyclovir, ganciclovir, and idoxuridine may also be observed in patients with atopic disease or in those who have taken topical corticosteroids.Citation119

Post-marketing surveys

In Phase IV post-marketing surveys of Zirgan conducted by Bausch and Lomb Incorporated, there have been occasional reports of eye irritation and injection, but they have been rare.Citation5 The same evaluations, however, have identified no unlabeled or unexpected adverse events that would be considered serious.Citation120 Often, symptoms of minor eye burning, tingling, and visual blurring were not severe enough to require discontinuation of the medication.Citation91 Seventy-five percent of patients queried after a full course of treatment for herpes simplex dendritic keratitis reported excellent, 22% good, and only 3% poor tolerability of the ganciclovir 0.15% gel.Citation65

Systemic toxicity

Systemic absorption of topical ganciclovir has been measured and found to be minimal.Citation5,Citation59 Under the standard initial dosing regimen for HSV dendritic keratitis of one drop five times per day, the estimated maximum daily dose of ganciclovir 0.15% gel is 0.375 mg. Even assuming complete systemic absorption, this represents only about 0.04% of the maintenance dose for oral valganciclovir (900 mg/day) and just 1% of the daily dose for intravenous ganciclovir (5 mg/kg/day, assuming 75 kg weight).Citation76 When patients with ulcerative herpes simplex keratitis instilled ganciclovir gel 0.15% five times daily for 11–15 days, plasma levels averaged 0.013 μg/mL. That level is 640-times lower than the Cmax (8.0 μg/mL) achieved after administration of 5 mg/kg of ganciclovir intravenously.Citation91 Because topical ganciclovir is absorbed systemically in such small amounts, its topical use would not be expected to produce systemic side effects.Citation7,Citation59,Citation79 Consistent with this expectation, none of the known hematological side effects of systemic ganciclovir have been observed with use of the gel formulation.Citation7 Drugs that inhibit rapidly replicating cell populations such as skin, bone marrow, and gastrointestinal mucosa may demonstrate additive toxicity when administered along with systemic ganciclovir. Interactions of this kind have not been documented in association with topical ganciclovir. Nevertheless, warnings remain in place for prescribers to take caution and to only use these drugs concomitantly when the benefits are felt to outweigh potential risks.Citation91

Ganciclovir gel is indicated for topical use only.Citation76 Accidental oral overdose of ganciclovir gel has not been reported. Spectrum Théa Pharmaceuticals, the manufacturer of Virgan®, believes that, even if inadvertent ingestion were to occur, significant systemic toxicity would be highly improbable.Citation91 There is only 7.5 mg of ganciclovir in a typical 5 g tube of the medication. The oral bioavailability of ganciclovir gel when taken with food is only 6%. By contrast, the daily intravenous therapeutic dose of ganciclovir is 500–1,000 mg. The drug is primarily excreted in unchanged form through glomerular filtration, with a systemic clearance rate of 3.64 mL/minute/kg.Citation91

Pediatric use

Oral acyclovir may be the preferred antiviral medication for therapy of HSV keratitis in the pediatric age group; it is especially convenient in younger children or infants since it can be administered as a liquid suspension.Citation121,Citation122 Oral valacyclovir or famciclovir are acceptable alternatives in older children.Citation121 The pediatric use of topical trifluridine, vidarabine, and acyclovir ointment has also been described.Citation121,Citation123,Citation124 There have been no reports to date on the use of topical ganciclovir specifically in children, although Phase II studies included children ≥2 years of age. Ganciclovir gel 0.15% has not been tested in pediatric patients under 2 years of age; its utility and safety in that age group has therefore not been established.Citation76

Safety in pregnancy and nursing; teratogenicity; effects on fertility

Similarly, ganciclovir gel’s safety for pregnant women and nursing mothers is unknown. For this reason it falls under Pregnancy Category C. Observations of adverse effects in animals have included carcinogenesis, mutagenesis, suppression of fertility, and maternal/fetal toxicity. Rabbits and mice were intravenously administered ganciclovir up to 17,000× the daily human ocular dose of 6.25 μg/kg/day. The drug in these high doses caused maternal toxicity, teratogenic effects, fetal growth retardation, and embryo death in rabbits. In mice, maternal toxicity, including decreased mating behavior and fertility, fetal toxicity, teratogenesis, and embryo lethality, were similarly observed. Oral and intravenous administration of ganciclovir to male mice and dogs, amounting to 30–1,600× the human daily ocular dose, also caused decreased fertility due to hypospermatogenesis.Citation76,Citation91 Spermatogenesis is inhibited reversibly at lower doses of systemic ganciclovir, but irreversibly using higher doses. Similarly, female infertility may also be permanent. In vivo tests were conducted, exposing mouse cells to ganciclovir, at levels exceeding the plasma levels of patients on ganciclovir gel treatment by 24,000× and 80,000×. Genetic point mutations and chromosomal damage were produced under these conditions.Citation91

The safety of ganciclovir gel for use in nursing mothers is unknown; there is no current information on whether the drug might be absorbed from ocular tissues in sufficient amounts to be detectable in breast milk. However, in a precautionary note, ganciclovir has been found to be secreted in the milk of laboratory animals; adverse effects were subsequently observed in the offspring.Citation3

Carcinogenesis

Ganciclovir was carcinogenic to mice at daily oral doses of 20 and 1,000 mg/kg/day – approximately 3,000× and 160,000×, respectively, the human ocular dose of 6.25 μg/kg/day. No carcinogenic effects, however, were observed in mice that ingested 1 mg/kg/day, representing 160× the daily human ocular dose. There was a small increase in tumor occurrence when plasma levels of ganciclovir in these animals reached about 50× the levels measured in humans after topical ganciclovir treatment.Citation11,Citation91

Based on this preclinical safety data, the drug is not recommended in pregnant and lactating females, and should be considered potentially carcinogenic and teratogenic.Citation91

Future applications and directions

HSV ocular disease

Ganciclovir gel may have several future applications beyond its current indication. Currently, ganciclovir ophthalmic gel 0.15% is not approved for use in the US in patients with geographic ulcers as a result of insufficient data to establish noninferiority to acyclovir.Citation1,Citation4 Further delineating its effectiveness against geographic ulcers might be a logical next step.

The third Herpetic Eye Disease Study Group study demonstrated a trend toward oral acyclovir being beneficial for herpetic iridocyclitis, but numbers were insufficient to achieve statistical significance.Citation125 There may be value in examining whether topical ganciclovir might also be useful in the management and treatment of this common manifestation of ocular herpes simplex. After topical administration, ganciclovir appears to reach therapeutic levels not only in the cornea but also the aqueous humor, although at lower concentrations in the latter location.Citation3,Citation7,Citation8,Citation57,Citation65 Initial studies of topical ganciclovir in rabbit eyes inoculated with HSV have demonstrated improvement of not only epithelial ulceration, but also of conjunctivitis, iritis, and corneal clouding.Citation96 It is unknown, of course, whether iridocyclitis would be treated with a similar dosing regimen as that used for HSV epithelial keratitis; higher doses of topical ganciclovir may be required.Citation59

In the second Herpetic Eye Disease Study, the question of oral acyclovir’s usefulness against necrotizing HSV keratitis was left unanswered due to insufficient numbers of patients with that condition recruited into the study.Citation67 If a study could recruit enough patients to achieve sufficient statistical power, it might answer whether antivirals such as topical ganciclovir are helpful against this uncommon form of herpes keratitis. In the meantime, it is more likely that information will trickle out over time through anecdotal reports.

Ganciclovir gel appears to have some capability to protect against recurrent herpes ulcerative keratitis, including after penetrating keratoplasty.Citation7,Citation8 Hlinomazová et al observed that, in patients with acyclovir-resistant HSV-1 keratitis and keratouveitis, the average relapse rate decreased from four to less than one per 12 months following a single 4-week period of ganciclovir gel therapy.Citation6 Ganciclovir ointment, used five times per day for 2 days, even at a concentration of just 0.03%, was effective in preventing HSV epithelial lesions in rabbit corneas.Citation100 Tabbara reported on 16 consecutive patients with history of recurrent herpetic keratitis who had undergone corneal transplantation due to ocular sequelae of the disease. In an open nonrandomized study, the patients applied ganciclovir 0.15% gel four times daily in the first week after penetrating keratoplasty, and then two times each day for a period of 1 year. Long term prophylaxis with topical ganciclovir gel afforded protection against recurrence of HSV keratitis in these subjects.Citation7,Citation8 Currently, oral acyclovir is the only antiviral medication that has been demonstrated to reduce the risk of recurrent HSV eye disease.Citation71 Ganciclovir gel may hold some potential as an alternative for HSV prophylaxis. The exact clinical setting, along with dosing frequency and length of treatment, still require further elucidation.Citation4,Citation7,Citation8

Adenoviral conjunctivitis

Some investigators have demonstrated evidence that ganciclovir gel may be useful against adenovirus – another DNA virus.Citation4,Citation5,Citation103,Citation126–Citation128 Epidemic keratoconjunctivitis (EKC) due to adenovirus is a significant public health nuisance that accounts for countless days lost from work and school, significant patient discomfort and inconvenience, and even long term ocular consequences, such as chronic keratitis, corneal scarring with decreased vision, and conjunctival scarring. Furthermore, 4.3% of patients with EKC can be coinfected with HSV-1;Citation129 15.2% of patients with HSV-1 infection may have coincident adenovirus present.Citation6 In vitro, ganciclovir inhibits adenoviral replication, including that of serotypes 8 and 19 – the most commonly encountered serotypes in EKC.Citation91 Trousdale et al, in studies of cotton rat eyes inoculated with adenovirus, found that topical ganciclovir, in a higher 3% dose, seemed to reduce incidence, titer, and duration of viral shedding.Citation130 Epstein et al examined the anti-adenovirus activity of ganciclovir 0.15% gel in a rabbit model. They found that active virions were cleared significantly faster in rabbits’ eyes that received the antiviral gel than in control eyes that did not receive the active agent. However, symptomatic improvement was not found to be statistically significant.Citation128

Outside of anecdotal reports, there have been a couple of small studies that have looked at the usefulness of ganciclovir gel for clinical EKC in humans. Vérin et al treated 36 patients at the onset of culture-proven adenovirus type 8 conjunctivitis with ganciclovir 0.15% gel four times a day. Ocular discomfort was reportedly relieved in 1 week, and no patients went on to develop keratitis. The investigators emphasized the importance of initiating therapy as early as possible in the clinical course.Citation131

Tabbara and Jarade conducted an investigation on 18 study patients with adenoviral keratoconjunctivitis. Subjects were randomized to receive either ganciclovir 0.15% gel or artificial tears four times per day. Mean recovery time for the ganciclovir gel group was 7.7 days compared to a mean of 18.5 days for the control group. Only two patients given ganciclovir developed subepithelial opacities, while seven of nine patients developed them using artificial tears. The difference was statistically significant (P<0.05). The authors concluded that ganciclovir 0.15% gel appears to be a safe and effective treatment for adenoviral keratoconjunctivitis.Citation126

Yabiku et al conducted a double-blind prospective trial to evaluate the efficacy and toxicity of ganciclovir 0.15% gel in the treatment of adenoviral conjunctivitis. Thirty-three patients with clinical adenovirus conjunctivitis were divided into ganciclovir-gel treatment and artificial-tear control groups. Patients in the treatment group experienced a statistically significant improvement of pain, itching, and photophobia symptoms during the 10 day course of their therapy. There were some trends toward both better and faster improvement of signs and symptoms in the ganciclovir group compared to controls (P=0.26). There was also a trend toward less household transmission in the ganciclovir-treated group (P=0.16). None of these trends, though, was statistically significant. Lastly, ocular complications after conjunctivitis were compared and found not to be significantly different between the two groups.Citation127

As of this writing, there are two ongoing trials assessing the efficacy of ganciclovir gel in the treatment of adenovirus conjunctivitis (ClinicalTrials.gov identification: NCT01533480Citation132 and NCT01600365Citation133).

Other herpesvirus eye diseases

Three cases of superficial and epithelial CMV keratitis have been reported: 1) in a patient who received a cardiac transplant; 2) in a patient after penetrating keratoplasty; and 3) spontaneous occurrence in a patient with AIDS.Citation134–Citation136 Excision of the diseased corneal button was reported to be curative in the patient who had acquired CMV keratitis after the keratoplasty.Citation135 In the patient with AIDS, antiviral therapy with oral acyclovir, oral famciclovir, topical foscarnet, topical trifluridine, and topical acyclovir were all ineffective; however, the patient expired before additional treatment options could be explored.Citation136 As noted previously in this review, some patients with CMV endotheliitis have responded to topical ganciclovir therapy.Citation81,Citation83 It is certainly conceivable that the antiviral gel might also have potential for use against the more superficial form of CMV keratitis.

Aggarwal et al recently reported on four immunocompromised patients with herpes zoster ophthalmicus-related pseudodendrites, unresponsive to oral valacyclovir. Each patient was administered ganciclovir 0.15% gel five times per day, and each had successful healing of their corneal lesions within 7 days. The gel drops were tapered to twice a day after the patients showed improvement; total duration of ganciclovir therapy ranged from 1 week to 2 months. In three of the four patients, topical prednisolone 1% was used concomitantly alongside ganciclovir gel. Visual acuity as well as corneal sensation improved in three out of the four patients.Citation137

Antitumor effects

Finally, ganciclovir may have potential as an antitumor drug. While ganciclovir cannot be phosphorylated by healthy mammalian cells, it can be phosphorylated by murine cells that contain the gene for herpes simplex thymidine kinase.Citation89 These transformed cells are easily killed by ganciclovir.Citation138 A similar inhibitory effect by ganciclovir is seen in murine melanoma cells transfected with the herpes simplex thymidine kinase gene.Citation138,Citation139 If tumor cells can be selectively transformed with a herpes simplex thymidine kinase gene, they may become susceptible to ganciclovir’s effects on their DNA replication.Citation89 This theory has already been shown to have clinical promise in the treatment of pediatric retinoblastoma patients with vitreous seeds. Eight patients had resolution or reduction of vitreous seeds after suicide gene therapy involving intravitreal injection of adenoviral vector containing herpes thymidine kinase gene, followed by administration of ganciclovir.Citation140 It is possible that topical ganciclovir might have potential to similarly inhibit neoplastic conjunctival and ocular surface cells, if gene therapy technology could be developed to deliver viral thymidine kinase gene into those cells. Topical drugs such as interferon alpha 2b, mitomycin C, and retinoic acid have already been used as both primary and adjuvant therapy for treatment of ocular surface squamous neoplasia, including conjunctival/corneal intraepithelial neoplasms.Citation141–Citation143 These agents have also been shown to have antitumor activity against conjunctival melanoma, as well as primary acquired melanosis with atypia.Citation144–Citation146 We are not aware of research being presently conducted to examine whether topical ganciclovir gel might play any similar role against ocular surface neoplasms.

Conclusion

Based on safety, efficacy, and tolerability, ganciclovir gel 0.15% should now be considered a front-line topical antiviral drug for the treatment of dendritic herpes simplex epithelial keratitis.Citation4,Citation57,Citation147 The gel poses less toxicity and requires a simpler dosing regimen than one of the main topical alternatives: trifluridine.Citation14,Citation61,Citation65,Citation92,Citation93 Additionally, the American Academy of Ophthalmology concluded, in their Preferred Practice Pattern® monograph on HSV epithelial keratitis, that the use of ganciclovir was associated with a better outcome overall than acyclovir topical ointment, despite similar healing rates found at 7 days.Citation16 This assessment is likely more related to ganciclovir gel’s favorable side effect and tolerability profile. The actual clinical efficacy of the various current antiviral choices have not been shown to be significantly different. As a result, the cost of treatment may turn out, more often than not, to be the deciding factor in which therapeutic option to choose. At a representative local pharmacy near our institution in Stony Brook, New York, the recent costs of a 2 week treatment course for the three drugs – Zirgan® 0.15% gel (1× 5 g tube), oral acyclovir (70× 400 mg tablets), and generic trifluridine 1% eye drops (1× 8 mL bottle) – were $273.62, $41.88, and $164.46, respectively (Centereach Walmart Store #2286, telephone communication, Jan, 2014). Prices may vary due to insurance policies and pharmacy location. The average wholesale prices for the three are $283.04, $216.97 (per 100 tablets), and $178.28, respectively. According to Bausch and Lomb Incorporated (HH DeCory, written communication, Jan, 2014), the wholesale acquisition cost for Zirgan® 0.15% gel is $235.87.

There exist several potential topics of interest for future examination and research. These include ganciclovir gel’s usefulness against HSV geographic ulcers, necrotizing keratitis, and iridocyclitis. Additionally there may be possible therapeutic applications for topical ganciclovir adenoviral keratoconjunctivitis, CMV keratitis including endotheliitis, and herpes zoster ophthalmicus pseudodendritic keratitis. Another intriguing question that may merit further investigation is whether ganciclovir gel may play any adjunctive role in the treatment of certain ocular surface tumors. The full spectrum of clinical applications for this newest of approved topical antiviral agents, therefore, remains to be determined.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- CroxtallJDGanciclovir ophthalmic gel 0.15%: in acute herpetic keratitis (dendritic ulcers)Drugs201171560361021443283

- LiesegangTJHerpes simplex virus epidemiology and ocular importanceCornea200120111311188989

- SahinAHamrahPAcute Herpetic Keratitis: What is the Role for Ganciclovir Ophthalmic Gel?Ophthalmol Eye Dis20124233423650455

- ColinJGanciclovir ophthalmic gel, 0.15%: a valuable tool for treating ocular herpesClin Ophthalmol20071444145319668521

- KaufmanHEHawWHGanciclovir ophthalmic gel 0.15%: safety and efficacy of a new treatment for herpes simplex keratitisCurr Eye Res201237765466022607463

- HlinomazováZLoukotováVHoráčkováMŠerýOThe treatment of HSV1 ocular infections using quantitative real-time PCR resultsActa Ophthalmol201290545646020553233

- TabbaraKFAl BalushiNTopical ganciclovir in the treatment of acute herpetic keratitisClin Ophthalmol2010490591220823931

- TabbaraKFTreatment of herpetic keratitisOphthalmology20051129164016139674

- XuFSternbergMRKottiriBJTrends in herpes simplex virus type 1 and type 2 seroprevalence in the United StatesJAMA2006296896497316926356

- LiesegangTJEpidemiology and natural history of ocular herpes simplex virus infection in Rochester, Minnesota, 1950–1982Trans Am Ophthalmol Soc1988866887242979036

- Zirgan® [patient’s guide]RochesterBausch and Lomb Incorporated2012 Available from: http://www.zirgan-info.com/healthcare_professionals/flipbooks/zirgan_detail_aid_fb/index.html

- LairsonDRBegleyCEReynoldsTFWilhelmusKRPrevention of herpes simplex virus eye disease: a cost-effectiveness analysisArch Ophthalmol2003121110812523894

- YoungRCHodgeDOLiesegangTJBaratzKHIncidence, recurrence, and outcomes of herpes simplex virus eye disease in Olmsted County, Minnesota, 1976–2007: the effect of oral antiviral prophylaxisArch Ophthalmol201012891178118320837803

- ColinJHohHBEastyDLGanciclovir ophthalmic gel (Virgan; 0.15%) in the treatment of herpes simplex keratitisCornea19971643933999220235

- LabetoulleMThe latest in herpes simplex keratitis therapyJ Fr Ophtalmol200427554755715179314

- ChingSSTFederRSHindmanHBWilhelmusKRMahFSHerpes Simplex Virus Epithelial Keratitis, Preferred Practice Pattern®Clinical QuestionsAmerican Academy of Ophthalmology201218

- MorissetteGFlamandLHerpesviruses and chromosomal integrationJ Virol20108423121001210920844040

- Robinet-CombesAColinJAtteintes herpétiques du segment antérieurParis, FranceEditions Techniques1993 Encycl Med Chir, Ophtalmol, 21-200 D-20 (7 p)

- FarooqAVShuklaDCorneal latency and transmission of herpes simplex virus-1Future Virol20116110110821436960

- Drugs: GanciclovirAIDSinfo Drug DatabaseUS Department of Health and Human Resources2013

- MellerickDMFraserNWPhysical state of the latent herpes simplex virus genome in a mouse model system: evidence suggesting an episomal stateVirology198715822652753035783

- DeshmaneSLFraserNWDuring latency, herpes simplex virus type 1 DNA is associated with nucleosomes in a chromatin structureJ Virol19896329439472536115

- HerpesvirusesBrooksGFCarrollKCButelJSMorseSAMietznerTAJawetz, Melnick, and Adelberg’s Medical Microbiology, 26eNew YorkMcGraw-Hill2013 Available from: http://accessmedicine.mhmedical.com.ezproxy.hsclib.sunysb.edu/content.aspx?bookid=504&Sectionid=40999955Accessed February 7, 2014

- SuthpinJEDanaMRFlorakisGJHammersmithKReidyJJLopatynskyMBasic and Clinical Science Course, External Disease and Cornea section 8San Francisco: American Academy of Ophthalmology200614324

- TomaHSMurinaATAreauxRGJrOcular HSV-1 latency, reactivation and recurrent diseaseSemin Ophthalmol200823424927318584563

- AsbellPAValacyclovir for the prevention of recurrent herpes simplex virus eye disease after excimer laser photokeratectomyTrans Am Ophthalmol Soc20009828530311190029

- DarougarSWishartMSViswalingamNDEpidemiological and clinical features of primary herpes simplex virus ocular infectionBr J Ophthalmol1985691263965025

- LiesegangTJMeltonLJ3rdDalyPJIlstrupDMEpidemiology of ocular herpes simplex. Incidence in Rochester, Minn, 1950 through 1982Arch Ophthalmol19891078115511592787981

- WishartMSDarougarSViswalingamNDRecurrent herpes simplex virus ocular infection: epidemiological and clinical featuresBr J Ophthalmol19877196696723663560

- ObaraYFurutaYTakasuTDistribution of herpes simplex virus types 1 and 2 genomes in human spinal ganglia studied by PCR and in situ hybridizationJ Med Virol19975221361429179758

- ZhengXReactivation and donor-host transmission of herpes simplex virus after corneal transplantationCornea200221Suppl 7S90S9312484706

- RemeijerLMaertzdorfJDoornenbalPVerjansGMOsterhausADHerpes simplex virus 1 transmission through corneal transplantationLancet2001357925444211273067

- KennedyDPClementCArceneauxRLBhattacharjeePSHuqTSHillJMOcular herpes simplex virus type 1: is the cornea a reservoir for viral latency or a fast pit stop?Cornea201130325125921304287

- DuTZhouGRoizmanBModulation of reactivation of latent herpes simplex virus 1 in ganglionic organ cultures by p300/CBP and STAT3Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A201311028E2621E262823788661

- ChidaYMaoXDoes psychosocial stress predict symptomatic herpes simplex virus recurrence? A meta-analytic investigation on prospective studiesBrain Behav Immun200923791792519409481

- LudemaCColeSRPooleCSmithJSSchoenbachVJWilhelmusKRAssociation between unprotected ultraviolet radiation exposurev and recurrence of ocular herpes simplex virusAm J Epidemiol2014179220821524142918

- MucciJJUtzVMGalorAFeuerWJengBHRecurrence rates of herpes simplex virus keratitis in contact lens and non-contact lens wearersEye Contact Lens200935418518719502988

- No authors listedPsychological stress and other potential triggers for recurrences of herpes simplex virus eye infections. Herpetic Eye Disease Study GroupArch Ophthalmol2000118121617162511115255

- RemeijerLDoornenbalPGeerardsAJRijneveldWABeekhuisWHNewly acquired herpes simplex virus keratitis after penetrating keratoplastyOphthalmology199710446486529111258

- BorderieVMMeritetJFChaumeilCCulture-proven herpetic keratitis after penetrating keratoplasty in patients with no previous history of herpes diseaseCornea200423211812415075879

- LevyJLapid-GortzakRKlempererILifshitzTHerpes simplex virus keratitis after laser in situ keratomilieusisJ Refract Surg200521440040216128340

- No authors listedPredictors of recurrent herpes simplex virus keratitis. Herpetic Eye Disease Study GroupCornea200120212312811248812

- GhoshehFRCremonaFARapuanoCJTrends in penetrating keratoplasty in the United States 1980–2005Int Ophthalmol200828314715318084724

- DarlingtonJKAdreanSDSchwabIRTrends of penetrating keratoplasty in the United States from 1980 to 2004Ophthalmology2006113122171217516996602

- LiuESlomovicARIndications for penetrating keratoplasty in Canada, 1986–1995Cornea19971644144199220238

- LindquistTDMcGlothanJSRotkisWMChandlerJWIndications for penetrating keratoplasty: 1980–1988Cornea19911032102162055026

- YahalomCMechoulamHSolomonARaiskupFDPeerJFrucht-PeryJForty years of changing indications in penetrating keratoplasty in IsraelCornea200524325625815778594

- SanoFTDantasPESilvinoWRTrends in the indications for penetrating keratoplastyArq Bras Oftalmol2008713400404 Portuguese18641829

- RobinJBGindiJJKohKAn update of the indications for penetrating keratoplasty. 1979 through 1983Arch Ophthalmol1986104187893510613

- InoueYShimomuraYFukudaMMulticentre clinical study of the herpes simplex virus immunochromatographic assay kit for the diagnosis of herpetic epithelial keratitisBr J Ophthalmol20139791108111223087417

- EdwardsMCloverGMBrookesNPendergrastDChaulkJMcGheeCNIndications for corneal transplantation in New Zealand: 1991–1999Cornea200221215215511862084

- WilliamsKALoweMTBartlettCMKellyLCosterDJThe Australian Corneal Graft Registry 2007 Report2007

- PatelNPKimTRapuanoCJCohenEJLaibsonPRIndications for and outcomes of repeat penetrating keratoplasty, 1989–1995Ophthalmology2000107471972410768334