Abstract

Background:

Several studies have examined the links between hypertension, vascular damage, and cognitive impairment. The functions most commonly involved seem to be those associated with memory and executive function.

Aims:

1) to report the cognitive evolution in a cohort of hypertensive patients, 2) to identify the affected domains, and 3) to correlate the results obtained with blood pressure measurements.

Materials and Methods:

Observational 6-year follow-up cohort study including both males and females aged ≥65 and ≤80 years, and hypertensive patients under treatment. Patients with a history of any of the following conditions were excluded: stroke, transient ischemic attack, diabetes mellitus, atrial fibrillation, cardiac surgery, dementia, or depression. Four neurocognitive evaluations were performed (at baseline and every 2 years). The tests used evaluated memory and executive function domain. Blood pressure was measured on every cognitive evaluation.

Results:

Sixty patients were followed for 76.4 ± 2.8 months. The average age at baseline was 72.5 ± 4.2 and 77.9 ± 4.6 at 6 years (65% were women). Two patients were lost to follow up (3.3%) and 8 patients died (13.3%).The density incidence for dementia was 0.6% patients per year (pt/y) (n = 3) and for depression was 1.6% pt/y (n = 12). No changes were observed in either memory impairment or the Mini Mental State Examination (MMSE) results (p = ns) during follow-up. A progressive impairment of the executive function was shown regardless of the blood pressure measurements.

Conclusion:

1) the incidence of dementia doubled to general population, 2) the initial memory impairment did not change during the evaluation period, 3) cognitive impairment worsened in the areas related to executive function (prefrontal cortex) regardless of the adequacy of anti-hypertensive treatment and blood pressure values.

Introduction

We have already described the difference between cognitive “impairment”, and the cognitive “decline” typically observed during aging, and concluded that in hypertensive patients the most commonly involved cognitive domains were long-term memory and executive functioning.Citation1 There is clear evidence that hypertension produces many pathological changes in the vascular system. Because it affects the brain, hypertension is the most important risk factor for stroke.Citation2 Apart from this complication, however, high blood pressure may damage the brain blood vessels, cause white matter lesions, and lead to both cortical and subcortical volume loss. These conditions may cause cognitive impairment, vascular dementia and, in some cases, even contribute to the progression of Alzheimer′s disease. Due to the long-term subclinical nature of these conditions, it is essential to use neuropsychological tests to study them.Citation3,Citation4 The increasing interest in the prevention, early detection, and management of cognitive impairment is the foundations of our investigation. The aims of this study were to observe the cognitive evolution, initially impaired, in our sample of hypertensive patients for 6 years, and to correlate our results with the blood pressure values (achieved therapeutic goals) and anti-hypertensive medications used.

Materials and methods

During the recruitment phase for 5 months, between December 2001 and April 2002, all patients seen in the outpatient cardiology clinic of the Hospital Español in Buenos Aires, Argentina, were invited to participate in the trial if they met the inclusion criteria. Both male and female patients ≥65 years of age with a hypertension diagnosis were included in this study. Individuals with a history of neurologic disease (stroke, transitory ischemic attack), psychiatric disease (depression or dementia according to the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-IV),Citation5 metabolic disease, diabetes mellitus (according to the standard of the American Diabetes Association),Citation6 dislipemia (defined as the use of cholesterol-lowering drugs, low-density lipoprotein >160 mg/dL, or nonhigh-density lipoprotein >190 mg/dL), and cardiovascular disease (heart failure, atrial fibrillation and cardiac surgery), as well as those on cholinesterase inhibitors, glutamatergic or antipsychotic inhibitors, were excluded. Sixty caucasian patients out of 520 consecutive patients signed an informed consent to participate in a 6-year follow-up trial. Hypertension was defined as systolic blood pressure (SBP) ≥140 mm Hg and/or diastolic blood pressure (DBP) ≥90 mm Hg at office visit and/or on three occasions throughout their clinical history or if they were taking specific antihypertensive medication. Blood pressure (BP) was measured according to both national and international guidelines,Citation7,Citation8 together with each cognitive evaluation. The anti-hypertensive medication was not modified during follow-up. Other clinical conditions (cardiac diseases, cerebral diseases, etc) were recorded. In the benzodiazepine-treated group, benzodiazepine was discontinued 72 hours before each cognitive evaluation. The trial was approved by an Independent Ethics Committee (IEC), pursuant to international Good Clinical Practice (GCP), the local regulations, and the Declaration of Helsinki and its amendments.

The neuropsychological assessment battery used in our Center included the following test: a) Folstein’s Mini Mental Statement Examination (MMSE)Citation9 cut-off point 24,Citation10 b) New York University (NYU) Paragraph Test to evaluate both short and long-term memory,Citation11 c) Trial Making TestCitation12 parts A and B (TMT A and B), d) the clock drawing test,Citation13 e) Stroop Test (Colors and Words),Citation14 and g) before each assessment patients answered a “Hospital Anxiety-Depression Scale” (HAD) questionnaire to evaluate whether the anxiety and/or depression – two conditions that alter the cognitive results – were present.Citation15 These tests were administered by neuropsychologists at the beginning of the study and then every 2 years.

Study design and statistics

This is an observational, cohort, 6-year follow up study. The SPSS 17.0 statistic package was used. While the categorical variables are expressed in percentages, the continuous variables are expressed with mean ± standard deviation (SD). For paired samples, the t-test was used. For analysis of variance, ANOVA was used, either parametric or nonparametric Kruskall–Wallis when the distribution was not gaussian or the test used points. The statistical tests were performed for a significance level <0.05.

Results

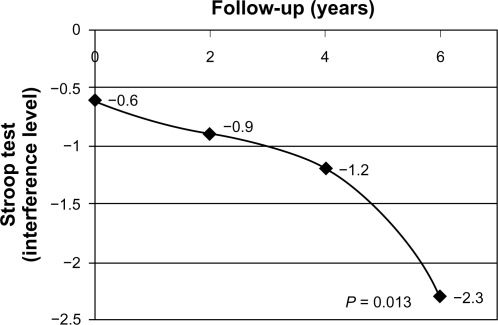

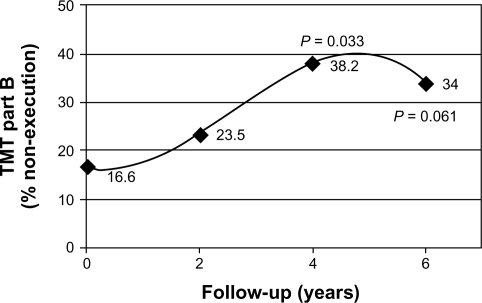

The general baseline characteristics of the group, blood pressure, schooling, age (72.5 ± 4.2 years) and the proportion of patients by gender (women 56.6% vs 65%), were included in . After 6 years of follow-up, the average age of the hypertensive patients was 77.9 ± 4.6 years. At the time of enrollment 28.3% of the hypertensive patients were not controlled and hypertension had been present for 10.2 ± 8.2 (range, 5–30) years. The evolution of the cognitive domains studied (average ± SD) after 76.4 ± 2.8 months of follow-up is shown in . During follow-up, 2 patients were lost to follow up (3.3%) and 8 patients died (13.3%) (). Three patients developed dementia (density incidence 0.6% pt/y) and were excluded from the following neuropsychological tests. The depression density incidence was 1.6% pt/y (n = 12). Patients with depression were treated and none had clinical signs at the time of evaluation. Memory impairment both in the short and long term remained unchanged during follow-up (baseline short-term memory 4 ± 2.1 vs final short-term memory 5 ± 2.4, pt = ns; basal long-term memory 6 ±2.5 vs final long-term memory 6 ±2.8, pt = ns). Throughout follow-up the results of the MMSE were normal (baseline 28 ± 1.6 vs final points 29 ± 2.2, pt = ns). A more marked impairment was observed in tests evaluating executive function. Performance in the Stroop test decreased throughout the follow-up showing more interference (basal results −0.6 ± 5.8 vs final results −2.3 ± 8.6, P = 0.031) (). The capacity to perform TMT part B progressively decreased showing statistical significance at 4 years compared with the basal result (16.6% [n = 10] vs 38.2% (n = 18), pt = 0.033), whereas after 6 years the downward tendency was (16.6% [n = 10] vs 34% [n = 16], pt = 0.061) (). The results of the cognitive tests showed no relationship with SBP or DBP values or pulse pressure (PP). The antihypertensive treatment was not modified by the investigators. When compared the cognitive performance with the different classes of antihypertensive drugs, used in monotheraphy or combined therapy, no differences were shown.

Figure 1 Stroop test change during follow-up (expressed as a level of interference between colors and words).

Figure 2 Trial Making Test part B change during follow-up (expressed as % of patients who did not perform the test).

Table 1 General characteristics of the hypertensive patients

Table 2 Cognitive evolution during the follow-up

Table 3 Mortality causes

Discussion

The relationship between the vascular damage caused by hypertension in brain structures, and the development of cognitive disorders and/or dementia several years later, has been widely investigated in epidemiological longitudinal studies.Citation16–Citation23 However, not all cognitive domains are equally affected by hypertension. In previous observations we showed that the executive functions related to the prefrontal cortex in hypertensive patients were more affected than those of patients with normal blood pressure.Citation1

The vulnerability to hypoxia and cerebral hypoperfusion is not homogenous in all regions of the brain.Citation24 The frontal lobes – particularly the prefrontal cortex – are more vulnerable to aging and even more to the effects of hypertension because of their phylogenetically younger structures.Citation25

A study of frontal function in hypertensive nonhuman primates (rhesus Macaque mulatta monkeys) concluded that in this model of cerebral vascular damage, the abstraction capacity and the executive function were both altered compared with frontal function in nonhypertensive monkeys.Citation26 Sabatini et al observed that anti-hypertensive treatment with different calcium antagonists increased the cellularity of all layers of the prefrontal cortex in spontaneously hypertensive rats (SHR).Citation27

The frontal lobes, representing 29% of the cortex and the most advanced functions of the brain, called executive functions, depend on the integrity of this lobes.Citation28 Three-way circuits connecting the frontal lobes with the subcortex structures and clinical behavioral syndromes depend on the damaged circuit.Citation29 In our study, the hypertensive patients showed a progressive impairment of executive function during the years studied, reflected by means of the TMT-B and the Stroop test.

The activity of the frontal lobes is strictly related to blood flow.Citation30 These regional brain flow changes are clearly visible in hypertensive patients, which affects their cognitive performance; it seems that, with the passing of time, the duration of hypertension contributes significantly to these changes.Citation24,Citation31 However, in the same way that the loss of secondary vasomotor capacity in hypertensive disorders leads to the redistribution of blood flow as a mechanism of adaptation, cognitive activities also use these mechanisms in order to perform complex activities with limited blood flow. Likewise, cognitive deficits are difficult to detect using conventional tests and subclinical disorders occur within years. This may explain why the MMSE, a low sensitivity and low specificity though useful test, did not change during follow-up. Consequently we had to use specific tests able to detect failure in executive functions.

On the other hand, the basal long-term memory impairment did not show a negative evolution during follow-up, despite being one of the first cognitive domains involved and it is the most common chief complaint in this type of patients.Citation32

A possible hypothesis for these associations in hypertensive patients is probably due to the direct consequences of the demyelinization (caused by hypoxia and consecutive ischemia),Citation23 and may cause the “disconnection” of subcortical–cortical loops.Citation33,Citation34 This lack of communication between the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex and the nuclei of the base by means of the caudate nucleus may be responsible for the “executive dysfunction”.

Depression is a common and under diagnosed symptom in elderly people, characterized mainly by cognitive symptoms (including slow thinking and volition-affected behaviour), which depend on the integrity of the frontal lobes and make the mind rigid.Citation35 However, the density incidence for depression is within the expected range in patients >65 years old (1.6% pt/y),Citation36 whereas the incidence density for dementia doubled compared with the general population (0.6% pt/y). Many of the cohorts studied have no selective screening for cardiovascular diseases that may appear as confounders or disparities related to the schooling. Our cohort though small has been carefully classified and followed for a reasonable time in order to observe cognitive changes.

Lastly, the blood pressure values during follow-up show a group of well-controlled patients, despite the fact that cognitive impairment grew worse and, although the sample is small no differences were observed in cognitive tests when analyzing patients according to BP values divided into controlled (≤139 and/or ≤89 mmHg) and noncontrolled (≥140 and/or ≥90 mmHg). This result also shows the need to do systematic neuropsychological screening when hypertensive patients are clinically examined so as to detect a possibly very narrow “window space” to intervene and stop the progression of cognitive impairment. We did not notice any changes in length of time of the disease or class of anti-hypertensive drugs used.

For a long time now, frontal lobes were called silent lobes. It is beyond doubt that hypertension is a risk factor for cognitive impairment, dementia, and/or depression. Both memory and executive functions seem to become impaired more often. The “dys-executive” syndrome (prefrontal domains) appears prematurely and its evolution seems to be progressive compared with memory, which seems to be affected more slowly. The unfavorable cognitive evolution does not seem to be related to the BP values or the antihypertensive treatments.

Acknowledgements

We thank Jonathan Feldman for the translation of this article and CERTUS Research Group for their invaluable assistance.

Disclosure

This work was not supported financially by any institution and the authors declare no competing interests.

References

- VicarioAMartinezCDBarretoDDíaz CasaleANicolosiLHypertension and cognitive decline: impact on executive functionJ Clin Hypertens20057598604

- LewingtonSClarkeRQizilbachNProspective Study Collaboration. Age-specific relevance of usual blood pressure to vascular mortality: a meta-analysis of individual data for one million adults in 61 prospective studiesLancet20023601903191312493255

- VicarioAMartinezCDEvaluación del daño funcional del cerebro en pacientes hipertensos: empleo de un Examen Cognitivo MinimoRev Fed Arg Cardiol200736146151 http://www.fac.org.ar/1/revista/07v36n3/art_orig/art_ori01/vicario.pdf. Accessed April 21, 2011.

- VicarioACerezoGHTaraganoFEAllegriRSarasolaDEvaluación, Diagnóstico y Tratamiento de los Trastornos Cognitivos en pacientes con Enfermedad Vascular. Recomendaciones para la práctica clínica 2007Rev Fed Arg Cardiol200736Suppl 3S1S30 http://www.fac.org.ar/1/revista/07v36n2/gral/supl3_07.PDF. Accessed April 21, 2011.

- American Psychiatric AssociationDiagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders4th edWashington, DCAmerican Psychiatric Association Press1994

- Expert Committee on the Diagnosis and Classification of Diabetes MellitusReport of the expert committee on the diagnosis and classification of diabetes mellitusDiabetes Care200023Suppl 1S4S1912017675

- ManciaGDe BackerGDominiczakAAuthors/Task Force Members. 2007 ESH-ESC Practice Guidelines for the Management of Arterial Hypertension: ESH-ESC Task Force on the management of Arterial HypertensionJ Hypertens2007251751176217762635

- Consenso de Hipertensión ArterialConsejo Argentino de Hipertensión Arterial Dr. Eduardo Braun MenéndezRev Argent Cardiol200775Suppl 4S1S43

- FolsteinMFFolsteinSEMcHughPR“Mini-mental stat”. A practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinicianJ Psychiatr Res1975121891981202204

- AllegriRFOllariJAMangoneCAEl Mini Mental State Examination en la Argentina: Instrucciones para su administraciónRev Neurol Arg1999243135

- FerrisSNYU computerized test battery for assessing cognition in aging and dementiaPsychopharmacol Bull198846997023074325

- LezakMDHowiesonDBLoringDWNeuropsychological Assessment4th edNew YorkOxford University Press2004

- FreedmanMLeachKKaplanEClock Drawing: SA Neuropsychological AnalysisNew York. NYOxford University Press1994

- GoldenCJStroop Color and Word Test A Manual for Clinical and Experimental UsesWood Dale, IllinoisStoelting1978

- WilkinsonMJBPsychiatric screening in general practice: comparison of the general health questionnaire and the hospital anxiety depression scaleJ R Coll Gen Pract1988383113133255827

- WilkieFEisdoferCIntelligence and blood pressure in the agedScience19711729599625573571

- EliasFWolfPAD’AgostinoRBCobbJWhiteLRUntreated blood pressure level is inversely related to cognitive functioning: the Framingham StudyAm J Epidemiol19931383533648213741

- LaunerLJRossGWPetrovichHMidlife blood pressure and dementia: Honolulu-Asian Aging StudyNeurobiol Aging200021495510794848

- GuoZFratiglioniLWinbladBViitanenMBlood pressure and performance on the Mini-Mental State Examination in the very old. Cross-sectional and longitudinal data from the Kungsholmen ProjectAm J Epidemiol1997145110611139199540

- KilanderLNymanHBobergMHanssonLLithellHHypertension is related to cognitive impairment: a 20-year follow-up of 999 menHypertension1998317807869495261

- SkoogILernfeltBLandahiSFifteen-year longitudinal study of blood pressure and dementiaLancet1996347114111458609748

- De LeeuwFEde GrootJCOudkerkMHypertension and white matter lesions in a prospective cohort studyBrain200212576577211912110

- VermeerSePrinsNDden HeijerTSilent brain infarctions and the risk of dementia and cognitive declineN Engl J Med20033481215122212660385

- Beason-HeldLLMoghekarAZondermanABKrautMAResnickSMLongitudinal changes in cerebral blood flow in the older hypertensive brainStroke2007381766177317510458

- JacksonJOn some implications of dissolution of the nervous systemLondon Medical Press and Circular18822411414

- MooreTLKillianyRJRoseneDLPrustySHollanderWMossMBImpairment of executive function induced by hypertension in the rhesus monkey (Macaca mulatta)Behav Neurosci200211638739612049319

- SabbatiniMTomassoniDAmentaFHypertensive brain damage: comparative evaluation of protective effect of treatment with dyhridopyridine derivatives in spontaneously hypertensive ratsMech Aging Dev20011222085210511589925

- GoldbergEThe conductor: A closer look at the frontal lobesGoldbergEThe Executive Brain Frontal Lobes and the Civilized Mind1st edNew YorkOxford University Press200169

- CummingsJLFrontal-subcortical circuits and human behaviorArch Neurol1979508738808352676

- BrownGGClarkCMLiuTTMeasurement of cerebral perfusion with arterial spin labeling: part 2. ApplicationsJ Int Neuropsychol Soc20071311317166298

- DaiWLopezOLCarmichaelOTBeckerJTKullerLHGachMAbnormal regional cerebral blood flow in cognitively normal elderly subjects with hypertensionStroke20083934935418174483

- RobertsJLClareLWoodsRTSubjective memory complaints and awareness of memory functioning in mild cognitive impairment: a systematic reviewDement Geriatr Cogn Disord2009289510919684399

- GeschwindNDisconnexion syndrome in animals and manBrain1965882372945318481

- GoldbergEBilderRMHughesJEAntinSPMattisSA reticulo-frontal disconnection syndromeCortex1989256876952612186

- GodinODoufouilCMaillardPWhite matter lesions as a predictor of depression in the elderly: the 3C-Dijon studyBiol Psychiatry20086366366917977521

- BeekmanATCopelandJRPrinceMJReview of community prevalence of depression in later lifeBr J Psychiatry199917430731110533549