Abstract

Venous thromboembolism (VTE), encompassing deep vein thrombosis and pulmonary embolism, represents a major cause of morbidity and mortality in patients with cancer. Low molecular weight heparins are the preferred option for anticoagulation in cancer patients according to current clinical practice guidelines. Fondaparinux may also have a place in prevention of VTE in hospitalized cancer patients with additional risk factors and for initial treatment of VTE. Although low molecular weight heparins and fondaparinux are effective and safe, they require daily subcutaneous administration, which may be problematic for many patients, particularly if long-term treatment is needed. Studying anticoagulant therapy in oncology patients is challenging because this patient group has an increased risk of VTE and bleeding during anticoagulant therapy compared with the population without cancer. Risk factors for increased VTE and bleeding risk in these patients include concomitant treatments (surgery, chemotherapy, placement of central venous catheters, radiotherapy, hormonal therapy, angiogenesis inhibitors, antiplatelet drugs), supportive therapies (ie, steroids, blood transfusion, white blood cell growth factors, and erythropoiesis-stimulating agents), and tumor-related factors (local vessel damage and invasion, abnormalities in platelet function, and number). New anticoagulants in development for prophylaxis and treatment of VTE include parenteral compounds for once-daily administration (ie, semuloparin) or once-weekly dosing (ie, idraparinux and idrabiotaparinux), as well as orally active compounds (ie, dabigatran, rivaroxaban, apixaban, edoxaban, betrixaban). In the present review, we discuss the pharmacology of the new anticoagulants, the results of clinical trials testing these new compounds in VTE, with special emphasis on studies that included cancer patients, and their potential advantages and drawbacks compared with existing therapies.

Introduction

Venous thromboembolism (VTE), encompassing deep vein thrombosis and pulmonary embolism, is the third leading cause of mortality due to circulatory diseases, second only to myocardial infarction and stroke.Citation1 On the other hand, cancer is responsible for 25% of all deaths in developed countries,Citation2 only exceeded by circulatory diseases. The two-way association between thrombosis and cancer has been well established since the first description by Jean Baptiste Bouillaud in 1823,Citation3 developed further by Armand Trousseau in 1865.Citation4 Patients with cancer have at least a six-fold increased risk of VTE compared with those without cancer,Citation5 and the diagnosis of VTE in cancer patients is associated with a 2–4-fold decreased survival during the first year.Citation6 Conversely, VTE can be the first sign of a cancer. Patients in the general population who develop symptomatic VTE have a 2–4-fold increased risk of cancer diagnosis in the first year after the VTE event.Citation7,Citation8

Studying anticoagulant therapy in oncology patients is challenging for several reasons. First, there are differences in VTE risk across the cancer population. Certain cancers (metastatic cancer, pancreas, ovary, lung, colon, stomach, prostate, and kidney adenocarcinomas, as well as malignant brain tumors and hematological malignancies) are strongly associated with the development of VTE.Citation9 Therapies for cancer, such as surgery, chemotherapy, and placement of central venous catheters, radiotherapy, hormonal manipulation (eg, tamoxifen), angiogenesis inhibitors (eg, bevacizumab, thalidomide, lenalidomide), and supportive therapies (ie, steroids, blood transfusion, white blood cell growth factors, and erythropoiesis-stimulating agents) may also increase the risk of VTE.Citation10,Citation11 Further, cancer patients have an increased risk of excessive bleeding during anticoagulant therapy compared with the population without cancer,Citation12 which may have several causes, including surgery, liver failure, chemotherapy, radiotherapy, use of antiplatelet drugs, or tumor-related factors (local vessel damage and invasion, abnormalities in platelet functioning and number).Citation10

Low molecular weight heparins (LMWH) are preferred over other anticoagulants (ie, fondaparinux, unfractionated heparin) or vitamin K antagonists (ie, warfarin, acenocoumarol) in cancer patients, according to clinical practice guidelines published by the American College of Chest Physicians,Citation13–Citation15 the GFTC initiative,Citation16 the European Society of Medical Oncology,Citation17 the American Society of Clinical Oncology,Citation18 and the National Comprehensive Cancer Network.Citation19 Fondaparinux may be an alternative to LMWH for prevention of VTE in hospitalized cancer patients with at least one additional risk factor for VTE, and for initial treatment of VTE, but it is not generally recommended for prevention of VTE after cancer surgery or for long-term or extended treatment of VTE ().Citation13–Citation15 Unfractionated heparin may provide an alternative to LMWH and fondaparinux in patients with renal impairment.Citation15 The preference for LMWH over vitamin K antagonists in cancer patients is based on several considerations: LMWH is more effective than vitamin K antagonists and is equally safe in the long-term treatment of VTE;Citation15 LMWH is easier to handle than vitamin K antagonists in the event of invasive procedures, which are frequent in cancer patients and may require rapid reversal with rapid reintroduction of anticoagulation; there may be an unpredictable response to vitamin K antagonist therapy in cancer patients because of the high risk of drug-drug interactions with cancer chemotherapy, as well as the frequent presence of vomiting associated with chemotherapy and subsequent poor oral absorption;Citation15 vitamin K antagonists have a slow onset of action, which implies a need for overlap with a parenteral anticoagulant in the event of acute VTE; and the narrow therapeutic window and variability in response to vitamin K antagonists implies that frequent anticoagulant monitoring [using the prothrombin time and its reporting as the international normalized ratio (INR)] is necessary to avoid subtherapeutic anticoagulation associated with an increased risk of thrombosis or excessive anticoagulation that increases the risk of bleeding. Such monitoring is inconvenient for patients and medical staff, and costly for health care payers.

Table 1 Summary of American College of Chest Physicians 2012 guideline recommendations for prophylaxis and treatment of venous thromboembolism in cancer patients

Despite LMWH and fondaparinux being effective and safe, they still require daily parenteral subcutaneous administration, which may be problematic for many patients, particularly if long-term treatment is needed. In addition, they are cleared mainly through the kidneys, and their use in patients with severe renal insufficiency may be problematic. LMWH is only partially neutralized by protamine, and no specific antidote is available for fondaparinux.

New anticoagulants include parenteral compounds for once-daily administration (ie, semuloparin) or once-weekly dosing (ie, idrabiotaparinux), as well as orally active compounds (ie, dabigatran, rivaroxaban, apixaban, edoxaban, betrixaban).

In this review, we discuss the pharmacology of the new anticoagulants and the results of clinical trials testing these compounds in VTE, with special emphasis on studies that included cancer patients. With this objective, we searched Medline (up to December 1, 2012) and clinical trial registries (ie, clinicaltrials.gov) using the terms “cancer”, “semuloparin”, “idraparinux”, “idrabiotaparinux”, “rivaroxaban”, “apixaban”, “edoxaban”, “betrixaban”, and “dabigatran”. We also searched regulatory agency websites (US Food and Drug Administration, European Medicines Agency) and relevant conference proceedings related to anticoagulation and cancer, ie, International Conference of Thrombosis and Hemostasis Issues in Cancer, International Society of Thrombosis and Hemostasis, American Society of Clinical Oncology, American Society of Hematology, and Mediterranean League Against Thromboembolic Diseases.

Mechanism of action of new anticoagulants

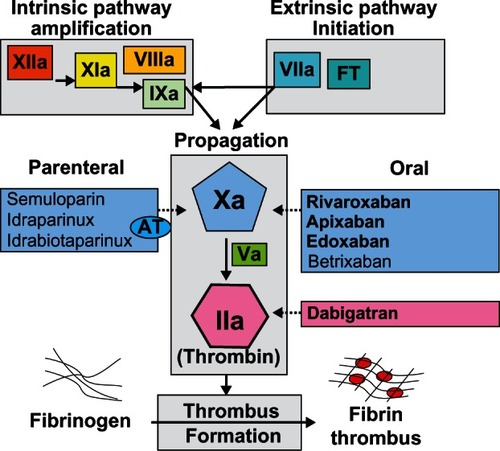

The new anticoagulants that are currently approved or in clinical development for indications related to the prophylaxis and treatment of VTE target activated Factor X (FXa) or activated factor II (FIIa, thrombin, ).

Figure 1 New anticoagulants and their targets in the coagulation cascade.*

FXa controls generation of thrombin, and inhibition of one molecule of FXa may result in inhibition of generation of 1000 molecules of FIIa.Citation20 Thrombin plays a central role in hemostasis by regulating blood coagulation and inducing platelet aggregation.Citation21 It is formed from its precursor, prothrombin, and converts fibrinogen to fibrin in the final step of the clotting cascade (). Thrombin also promotes numerous cellular effects, ie, it plays a role in inflammation and cellular proliferation, and displays mitogen activity in smooth muscle cells and endothelial cells, predominantly by activation of angiogenesis.Citation22 Preclinical data suggest that thrombin inhibition may result in inhibition of both tumor growth and metastases.Citation23,Citation24 Therefore, use of anticoagulation in cancer patients might be beneficial not only in preventing thrombotic events, but also as an adjuvant anticancer therapy.

FXa inhibitors block generation of thrombin, while thrombin inhibitors block the activity of thrombin. FXa inhibitors include parenteral drugs that indirectly inhibit FXa by binding to antithrombin (ie, semuloparin, idraparinux, idrabiotaparinux) and orally active agents that directly inhibit FXa (rivaroxaban, apixaban, edoxaban, betrixaban). Oral direct thrombin inhibitors include the prodrug dabigatran etexilate, AZD0837, and S35972.Citation25

Development of several promising new oral direct FXa inhibitors for VTE has recently been halted, including for darexaban (YM150, Astellas Pharma Inc, Tokyo, Japan),Citation26 letaxaban (TAK-442, Takeda Pharmaceutical Company Limited, Tokyo, Japan), eribaxaban (PD0348292, Pfizer Inc, New York, NY, USA),Citation27 AZD0837, and S35972. These new anticoagulants will not be discussed further in the review.

Among the new anticoagulants, dabigatran etexilate (Pradaxa®, Boehringer Ingelheim, Ingelheim, Germany), rivaroxaban (Xarelto®, Bayer HealthCare, Leverkusen, Germany), and apixaban (Eliquis®, Bristol-Myers Squibb, New York, NY, USA) are currently approved in the European Union, the US, and other regions in several indications related to anticoagulation, while edoxaban (Lixiana®, Daiichi-Sankyo Inc, Parsippany, NJ, USA) is approved in Japan for thromboprophylaxis after major orthopedic surgery ().

Table 2 Characteristics of old and new anticoagulants*

Novel parenteral indirect FXa inhibitors

Semuloparin

Semuloparin sodium (AVE5026, Mulsevo®, Sanof-Aventis, Bridgewater, NJ, USA) is a new ultralow molecular weight heparin obtained by phosphazene-promoted depolymerization of heparin from porcine intestinal mucosa, leading to a pool of polysaccharide chains with an individual molecular weight distribution (mean molecular weight 2000–3000 Da).Citation28–Citation30 It has predominantly anti-FXa activity (ratio anti-FXa/anti-FIIa approximately 80) and a half-life of 16–20 hours, which allows once-daily subcutaneous administration. Its excretion is mainly renal.Citation28 At equipotent doses, semuloparin did not affect bleeding parameters, whereas enoxaparin showed increased risk of hemorrhage in rats, rabbits, and dogs.Citation29 The anticoagulant effects of semuloparin are not neutralized by protamine.Citation31 Preliminary in vitro evaluation of semuloparin indicates a low risk for immune-mediated heparin-induced thrombocytopenia.Citation29

Semuloparin was at least as effective as enoxaparin in preventing VTE after total knee arthroplasty (SAVE-KNEE study)Citation32 and total hip replacement (SAVE-HIP1 and SAVE-HIP2 studies),Citation32 and was more effective than placebo for extended VTE prophylaxis after hip fracture surgery.Citation33 However, no superior efficacy to enoxaparin was shown for major VTE (after excluding asymptomatic distal deep vein thrombosis) in a pooled analysis,Citation34 and the risk of clinically relevant bleeding with semuloparin varied across trials.

Two additional studies were conducted in cancer patients undergoing chemotherapy (SAVE-ONCO)Citation35–Citation37 and in patients undergoing major abdominal surgery, the majority of them because of cancer (SAVE-ABDO).Citation36–Citation38 The results of these studies are shown in and discussed below.

Table 3 Clinical trials with new parenteral indirect FXa anticoagulants for prophylaxis and treatment of venous thromboembolism

VTE prophylaxis in medical patients undergoing chemotherapy

SAVE-ONCOCitation35–Citation37 was a double-blind multicenter trial evaluating the efficacy and safety of semuloparin for prevention of VTE in patients receiving chemotherapy for cancer. A total of 1150 patients with metastatic or locally advanced solid tumors and embarking on a course of chemotherapy were randomly assigned to receive subcutaneous semuloparin 20 mg once daily or placebo for a median of 3.5 months. The most common primary malignancies were lung (37%) or colorectal (29%) cancer, with a smaller proportion of patients having cancer of the stomach (13%), ovary (12%), pancreas (8%), or bladder (2%). Most patients (69%) had metastatic disease at study entry, and more than 90% of patients in this trial had Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status of 0 or 1.Citation36,Citation37 The most common chemotherapeutic agents included platinum compounds and pyrimidine analogs. In total, 42% of patients had at least one additional VTE risk factor, and 2.3% of patients had at least three VTE risk factors.

The primary efficacy outcome (composite of any symptomatic deep vein thrombosis, any nonfatal pulmonary embolism, and death related to VTE) occurred in 1.2% of patients (20/1608) receiving semuloparin, as compared with 3.4% (55/1604) receiving placebo (absolute risk difference −2.2%; hazard ratio [HR] 0.36; 95% confidence interval [CI] 0.21–0.60; P < 0.001). VTE-related death occurred in only 0.4% and 0.6% of patients receiving semuloparin and placebo, respectively. In relative terms, efficacy was consistent among subgroups defined according to the origin and stage of cancer and the baseline risk of VTE. However, the subgroup analyses also suggest that there may be a sizable variation in the absolute benefit depending on tumor type and baseline VTE risk between patients, with pancreatic subtype and a VTE risk score ≥ 3 being associated with greater absolute benefit (absolute risk reduction 8.5% and 3.9% versus placebo, respectively).Citation36,Citation37

The incidence of clinically relevant bleeding was 2.8% and 2.0% in the semuloparin and placebo groups, respectively (absolute risk difference +0.8%; HR 1.40; 95% CI 0.89–2.21). However, there were more patients with treatment-emergent bleeding events overall in the semuloparin group compared with the placebo group (20% versus 16%, respectively), including serious cases (1.9% versus 1.5%).Citation36 Rates of major bleeding were similar in both treatment groups (1.2% versus 1.1%). Fatal bleeding occurred in two and four patients in the semuloparin and placebo groups, respectively. However, major bleeding into a critical area or organ, as included in a US Food and Drug Administration analysis, was observed in seven patients in the semuloparin group and no patients in the placebo group. These cases included two pericardial, one intraocular (resulting in retinal detachment), one splenic, and three intracranial bleeds, of which one case was fatal.Citation37 Rates of all deaths during the overall study period (43.4% versus 44.5%)Citation35 and on-treatment deaths (15.7% versus 15.9%)Citation37 were similar in the two study groups.

In conclusion, semuloparin reduced the incidence of VTE in patients receiving chemotherapy for cancer, with sizable variation in the absolute benefit depending on tumor type and baseline VTE risk. Although there was no significant increase in overall major bleeding, there was a trend towards a higher risk of bleeding into a critical area or organ with semuloparin in comparison with placebo. No trend towards a survival benefit was noted.

VTE prophylaxis in major abdominal surgery

SAVE-ABDOCitation36–Citation38 was a randomized, active-controlled trial for the prevention of VTE in patients undergoing major abdominal surgery for indications other than disease of the liver, uterus, or prostate. Patients younger than 60 years of age had to have one of the following additional risk factors: cancer surgery, history of VTE, body mass index ≥ 30 kg/m2, chronic heart failure, chronic respiratory failure, or inflammatory bowel disease. A total of 4413 patients were randomized 1:1 to receive either semuloparin 20 mg subcutaneous once daily started postoperatively or enoxaparin 40 mg subcutaneous once daily started preoperatively for a duration of 7–10 days after surgery, of which 3030 patients were assessable for efficacy. This trial failed to meet its primary efficacy endpoint of any VTE or all-cause death in a noninferiority comparison of semuloparin versus enoxaparin (6.3% versus 5.5%; odds ratio [OR] 1.16; 95% CI 0.87–1.54; noninferiority margin 1.25).Citation36,Citation37 Rates of major VTE or all-cause deaths (secondary endpoint) were similar in the semuloparin and enoxaparin groups (2.2% versus 2.3%; OR 0.95; 95% CI 0.61–1.49).

Eighty-one percent (n = 2451) of the primary efficacy population was composed of patients with cancer and undergoing oncological surgery. An exploratory analysis by the US Food and Drug Administration in the subgroup of patients with cancer showed a numerically higher proportion of subjects with VTE events in the semuloparin arm than the enoxaparin arm (7.1% versus 5.9%; OR 1.23; 95% CI 0.89–1.69).Citation37 In the overall study population, semuloparin was associated with less clinically relevant bleeding (2.9% versus 4.5%; OR 0.63; 95% CI 0.46–0.87) and less major bleeding (4.1% versus 5.7%; OR 0.71; 95% CI 0.54–0.93) than enoxaparin.

Idraparinux sodium

Idraparinux sodium (SR34006, Sanof-Aventis and Organon Pharmaceuticals Inc, Roseland, NJ, USA), investigated in the SANORG 34006 trial, is a long-acting synthetic molecule, developed based on the native pentasaccharide sequence that binds to antithrombin, thus indirectly inhibiting FXa activity.Citation39,Citation40 Idraparinux is almost completely absorbed after subcutaneous injection and the time to maximum concentration is about 4 hours after subcutaneous administration. It has a half-life of 120 hours in healthy subjectsCitation41 and 66 days after multiple doses in patients,Citation42 allowing for once-weekly administration. It is excreted unchanged via the kidneys. Therefore, there is a risk of accumulation in patients with renal insufficiency. The anticoagulant effect may persist for 3–4 months after termination of therapy.Citation43

Acute and long-term treatment of deep vein thrombosis

In a randomized, open-label, noninferiority Phase III trial in patients with deep vein thrombosis (van Gogh-DVT, n = 2904), idraparinux 2.5 mg once weekly was as effective as standard therapy (heparin followed by an adjusted-dose vitamin K antagonist) administered for 3–6 months.Citation44 The incidence of recurrence at day 92 was 2.9% in the idraparinux group as compared with 3.0% in the standard therapy group (OR 0.98; 95% CI 0.63–1.50), a result that satisfied the prespecified noninferiority requirement (upper limit of the 95% CI for the OR for documented symptomatic recurrent VTE < 2). At 6 months, clinically relevant bleeding rates were similar (8.3% versus 8.1%). A post hoc analysis of the subgroup of patients with cancer (n = 421) showed that idraparinux was as effective as a vitamin K antagonist with respect to recurrent VTE (idraparinux 2.5% versus standard therapy 6.4%; HR 0.39; 95% CI 0.14–1.11), with similar rates of bleeding events (OR 0.89; 95% CI 0.50–1.59) and death (HR 0.99; 95% CI 0.66–1.48).Citation45

Acute and long-term treatment of pulmonary embolism

In patients with pulmonary embolism (van Gogh-PE trial, n = 2215), idraparinux was less effective than standard therapy.Citation44 The incidence of recurrence at day 92 was 3.4% in the idraparinux 2.5 mg once weekly group and 1.6% in the standard therapy group (OR 2.14; 95% CI 1.21–3.78). Clinically relevant bleeding rates at 6 months were similar (7.7% versus 9.7%) and death rates were higher with idraparinux than with standard therapy (6.4% versus 4.4%; P = 0.04). A total of 320 patients had a history of cancer. No subgroup analysis of patients with cancer is available from the van Gogh-PE study.

Extended treatment of VTE

During a 6-month extension of thromboprophylaxis (van Gogh-Extension trial, n = 1215),Citation46 idraparinux 2.5 mg once weekly was more effective than placebo in preventing recurrent VTE (1.0% versus 3.7%; OR 0.27; 95% CI 0.11–0.66; P = 0.002) but was associated with an excessive risk of major hemorrhage (1.9% versus 0%; P < 0.001), including three fatal intracranial bleeds. A total of 120 patients had a history of cancer, but no efficacy or safety data were reported for this subgroup.

Follow-up data from the van Gogh clinical trials suggests that the very long elimination half-life of idraparinux may explain the increase in bleeding complications in the extension trial.Citation47 Clinical development of idraparinux, which has no antidote, was halted in favor of idrabiotaparinux, for which an antidote (avidin) is readily available.

Idrabiotaparinux

Idrabiotaparinux (biotinylated idraparinux, SSR126517E, Sanofi-Aventis) is a long-acting synthetic pentasaccharide with pharmacokinetic and anticoagulant properties similar to those of the previous compound, idraparinux ().Citation40–Citation42 Unlike idraparinux, the anticoagulant effect of idrabiotaparinux can be rapidly neutralized because of its binding to the biotin moiety following intravenous infusion of avidin (EP5001), an egg-derived protein.Citation48 The main results of the studies using idrabiotaparinux in the treatment of VTE are summarized in and are discussed below. No clinical studies are currently ongoing with this compound.

Acute and long-term treatment of deep vein thrombosis

The EQUINOX studyCitation49 was a randomized double-blind trial comparing the efficacy and safety of idrabiotaparinux 3 mg and idraparinux 2.5 mg, each given subcutaneously once weekly for 6 months in patients with acute symptomatic deep vein thrombosis (). A total of 757 patients underwent randomization, of whom 5.2% (n = 39) had active cancer. No efficacy or safety data were reported in this subpopulation. In the overall population, rates of recurrent VTE and of fatal or nonfatal pulmonary embolism were similar between idrabiotaparinux (2.3%, nine of 386 patients) and idraparinux (3.2%, 12 of 371 patients) at 6 months (absolute risk difference −0.9%; 95% CI −3.2 to 1.4). The study was not powered for efficacy, so no definitive conclusions can be made in this regard. There was less clinically relevant bleeding (5.2% versus 7.3%) and less major bleeding (0.8% versus 3.8%) with idrabiotaparinux than with idraparinux (). The finding of lower bleeding rates with idrabiotaparinux than with idraparinux is intriguing, given that both drugs exerted similar inhibition of FXa activity. This difference cannot be explained by the administration of avidin, because it occurred in only three patients during the 6-month study period.

Long-term treatment of pulmonary embolism

CASSIOPEACitation50 was a randomized, double-blind, double-dummy, noninferiority trial that compared the efficacy and safety of idrabiotaparinux versus warfarin in the long-term treatment of symptomatic pulmonary embolism. Patients were randomized to receive initial treatment for acute pulmonary embolism of enoxaparin 1 mg/kg subcutaneously twice daily for 5–10 days, followed by idrabiotaparinux (starting dose 3 mg subcutaneously once weekly) or enoxaparin 1 mg/kg subcutaneously twice daily or 5–10 days, overlapping with and followed by dose-adjusted warfarin (INR 2-3). These regimens lasted 3 or 6 months depending on clinical presentation. A total of 3202 patients were enrolled, of whom 5.9% (190 patients) had cancer present or treated in the last 6 months. No subgroup analysis for the cancer patients is available. Recurrent VTE at 99 days (main outcome) was similar in both treatment groups (2% versus 3%; OR 0.79; 95% CI 0.50–1.25; prespecified noninferiority limit 2.0; noninferiority P = 0.0001). There were fewer clinically relevant bleeding episodes (main safety outcome) in patients in the enoxaparin-idrabiotaparinux group than in the enoxaparin-warfarin group (5% versus 7%: OR 0.67; 95% CI 0.49–0.91; P = 0.0098). Differences in outcome were similar in patients treated to 6 months. In conclusion, idrabiotaparinux could provide an alternative to warfarin for the long-term treatment of pulmonary embolism, and seems to be associated with reduced bleeding.

Novel oral direct Factor Xa inhibitors

Rivaroxaban

Rivaroxaban (BAY 59-7939, Xarelto®, Bayer HealthCare) is an oxazolidinone derivative with a molecular weight of 436 Da and high selectivity for direct inhibition of FXa ().Citation51 In healthy subjects, rivaroxaban was well tolerated, with a predictable pharmacological profile for single and repeated doses.Citation51,Citation52 Maximum inhibition of FXa activity was 75% after a single oral dose of 40 mg.Citation53 Peak plasma levels are reached in about 3 hours. Half-life ranges from a mean of 7 (5–9) hours in healthy volunteers to 12 (11–13) hours in elderly people. Rivaroxaban is metabolized in the liver by cytochrome P450 (CYP3)A4 and, to a lesser extent, via CYP2J2.Citation54 Rivaroxaban is mainly excreted by the kidneys () and to a lesser extent by the bile and intestines via the P-glycoprotein transport system. Caution must be exercised in patients receiving treatment with potent inhibitors of both CYP3A4 and P-glycoprotein, such as ketoconazole or ritonavir.Citation55

Rivaroxaban is currently approved in the European Union, the US, and other countries for VTE prophylaxis after total hip replacement or total knee arthroplasty on the basis of the RECORD1-4 studies,Citation56–Citation59 as well as for stroke prevention in atrial fibrillation based on the ROCKET-AF clinical trial.Citation60 Rivaroxaban is also approved in several regions for the acute and long-term treatment of VTE as a result of the positive results obtained in the EINSTEIN studies.Citation61,Citation62 A pilot study (Catheter 2) is currently investigating rivaroxaban for the treatment of central line-associated blood clots in cancer patients (n = 72, ClinicalTrials.gov ID, NCT01708850).

The main results of the completed Phase III studies for nonsurgical VTE prophylaxis or treatment of VTE ( and , respectively), are discussed below, paying special attention to data available for cancer patients.

Table 4 Clinical trials with new oral anticoagulants for venous thromboembolism prophylaxis in nonsurgical patients

Table 5 Clinical trials with new oral anticoagulants for treatment of venous thromboembolism

VTE prophylaxis in medical patients

The MAGELLAN studyCitation63–Citation65 was a multinational, multicenter, randomized, double-blind controlled trial in which medical patients aged ≥ 40 years hospitalized for acute medical illness with decreased level of mobility were randomized to oral rivaroxaban 10 mg once daily for 35 days or enoxaparin 40 mg for 10 days followed by placebo until completion of 35 days of treatment. A total of 8101 patients were randomized of whom 584 (7%) had concomitant cancer. The primary efficacy outcome (composite of asymptomatic proximal deep vein thrombosis of the lower limbs detected by ultrasonography, proximal or distal symptomatic deep vein thrombosis, or symptomatic pulmonary embolism) occurred in 2.7% of patients in each group (relative risk [RR] 0.97; 95% CI 0.71–1.33; RR noninferiority margin 1.5; noninferiority P value = 0.0025) on day 10, and in 4.4% of patients on rivaroxaban and in 5.7% of patients on enoxaparin followed by placebo (RR0.77; 95% CI 0.62–0.96; superiority P value 0.0211) on day 35.

Rivaroxaban demonstrated more clinically relevant bleeding (main safety outcome) than enoxaparin on day 10 (2.8% versus 1.2%; RR 2.3; 95%CI 1.63–3.17; P < 0.0001) and day 35 (4.1% versus 1.7%;RR2.5;95%CI 1.85–3.25; P < 0.0001). Major bleeding was also more frequent with rivaroxaban than with enoxaparin on day 10 (0.6% versus 0.3%; RR 2.2; 95% CI 1.07–4.45; P = 0.0318) and day 35 (1.1% versus 0.4%; RR 2.9; 95% CI 1.60–5.15; P < 0.001). Death rates were similar in both groups by day 35 (5.1% versus 4.8%).

In subgroup analyses, extended thromboprophylaxis with rivaroxaban showed a nonsignificant trend towards less efficacy than short-term enoxaparin in patients with active cancer on day 35 (9.9% versus 7.4%; RR 1.34; 95% CI 0.71–2.54),Citation64,Citation65 while clinically relevant bleeding was more frequent with rivaroxaban than with enoxaparin plus placebo onday35 (5.4% versus 1.7%,Citation64 RR 3.16; 95%CI 1.17–8.50; authors’ calculation). In conclusion, rivaroxaban was noninferior to enoxaparin for short-term thromboprophylaxis and superior to enoxaparin plus placebo for extended thromboprophylaxis. The efficacy of rivaroxaban was consistent across all covariates analyzed with the exception of active cancer.Citation65 Bleeding rates were significantly increased with rivaroxaban in patients with cancer and in the overall study population.

Acute and long-term treatment of deep vein thrombosis and pulmonary embolism

The EINSTEIN-DVT studyCitation61 was an open-label, randomized event-driven, noninferiority study that compared oral rivaroxaban alone (15 mg twice daily for 3 weeks, followed by 20 mg once daily) subcutaneous enoxaparin followed by a vitamin K antagonist (either warfarin or acenocoumarol) for 3, 6, or 12 months in patients with acute, symptomatic deep vein thrombosis. The study included 3449 patients, of whom 207 (6%) had active cancer. Rivaroxaban had noninferior efficacy for the primary outcome of symptomatic recurrent VTE (2.1% versus 3.0%; HR 0.68; 95% CI 0.44–1.04; noninferiority P value < 0.001). Clinically relevant bleeding (primary safety outcome) occurred in 8.1% of patients in each group (). In cancer patients, both groups had similar rates of recurrent VTE (3.4% versus 5.6%) and clinically relevant bleeding (14.4% versus 15.9%).

The EINSTEIN-PE studyCitation62 was a randomized, open-label, event-driven, noninferiority trial involving 4832 patients who had acute symptomatic pulmonary embolism with or without deep vein thrombosis. The authors compared rivaroxaban (15 mg twice daily for 3 weeks, followed by 20 mg once daily) with standard therapy of enoxaparin followed by an adjusted-dose vitamin K antagonist for 3, 6, or 12 months. A total of 4833 patients underwent randomization, of whom 223 (4.6%) had active cancer. Rivaroxaban was noninferior to standard therapy for the primary outcome of symptomatic recurrent VTE (2.1% versus 1.8%; HR 1.12; 95% CI 0.75–1.68; noninferiority margin 2.0; P = 0.003). The primary safety outcome occurred at similar rates in the rivaroxaban and standard therapy groups (10.3% versus 11.4%, respectively; HR 0.90; 95% CI 0.76–1.07; P = 0.23). Major bleeding rates with rivaroxaban were lower than with standard treatment (1.1% versus 2.2%; HR 0.49; 95% CI 0.31–0.79; P = 0.003). Deaths were numerically higher with rivaroxaban than with standard treatment (58 versus 50; P = 0.53). In cancer patients, both groups had similar rates of recurrent VTE (1.8% versus 2.8%) and clinically relevant bleeding (12.3% versus 9.3%).

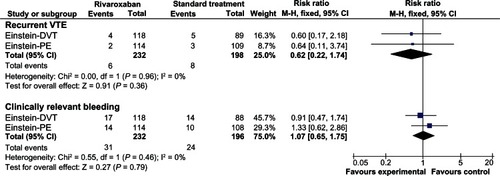

The overall data from the EINSTEIN-DVT and EINSTEIN-PE studies suggest that the single-drug approach to the initial and long-term treatment of deep vein thrombosis or pulmonary embolism with rivaroxaban is at least as effective and safe as standard treatment with enoxaparin and a vitamin K antagonist. We have conducted a pooled analysis of both studies comparing rivaroxaban and standard treatment in the subgroup of patients with cancer (), based on subgroup data reported in the original publications.Citation61,Citation62 The pooled analysis suggests that the treatment groups had a similar risk of recurrent VTE (RR 0.62; 95% CI 0.22–1.74) and clinically relevant bleeding (RR 1.07; 95% CI 0.65–1.75) in cancer patients.

Extended treatment of deep vein thrombosis and pulmonary embolism

The EINSTEIN-extension studyCitation61 was a double-blind, randomized, event-driven, superiority study that compared rivaroxaban 20 mg once daily with placebo for an additional 6 or 12 months in patients who had completed 6–12 months of treatment for VTE. The study included 1197 patients, of whom 54 (4.5%) had active cancer. Rivaroxaban had superior efficacy compared with placebo for the primary endpoint of symptomatic recurrent VTE (1.3% versus 7.1%; HR 0.18; 95% CI 0.09–0.39; P < 0.001). Major bleeding (the main safety outcome) occurred in four (0.7%) patients in the rivaroxaban group versus none in the placebo group (P = 0.11). Clinically relevant bleeding was more frequent with rivaroxaban than with placebo (6% versus 1.2%; HR 5.19; 95% CI 2.3–11.7). Three patients died during the study (one in the rivaroxaban group and two in the placebo group). No subgroup analysis in cancer patients is available for this study.

Apixaban

Apixaban (BMS-562247-01, Eliquis®, Bristol-Myers Squibb) is an oral, direct, and highly selective FXa inhibitor. Apixaban was effective in the prevention of experimental thrombosis at doses that preserve hemostasis in rabbits.Citation66 In humans, apixaban is absorbed relatively rapidly, with peak concentrations achieved approximately 3 hours post-dosing, and a mean terminal half-life ranging from 8 to 15 hours.Citation67 Apixaban is metabolized mainly via CYP3A4/5, with minor contributions from CYP1A2, 2C8, 2C9, 2C19, and 2J2.Citation68 Apixaban is also a substrate of the transport proteins, P- glycoprotein and breast cancer resistance protein.Citation68 Drug-drug interaction studies show a two-fold increase in exposure to apixaban after administration of potent inhibitors of CYP3A4 and P-glycoprotein (eg, ketoconazole), while the exposure to apixaban decreases by 50% after concomitant administration of potent inducers of CYP3A4 and P-glycoprotein (eg, rifampicin). Therefore, in these clinical situations, apixaban should be administered with caution.Citation67 Apixaban has multiple routes of elimination. Renal excretion of apixaban accounts for approximately 27% of total clearance ().Citation69

Apixaban is currently authorized in the European Union and other regions for VTE prophylaxis after total hip replacement or total knee arthroplasty on the basis of the ADVANCE1-3 studies,Citation70–Citation72 as well as for stroke prevention in atrial fibrillation based on the ARISTOTLE study.Citation73 The main results of the completed Phase II–III studies for nonsurgical VTE prophylaxis or treatment of VTE ( and , respectively) are discussed below, paying special attention to data available from cancer patients.

VTE prevention in medical patients on chemotherapy

ADVOCATECitation74 was a Phase II pilot study evaluating whether apixaban would be well tolerated and acceptable in cancer patients receiving chemotherapy. The study enrolled patients receiving either first-line or second-line chemotherapy for advanced or metastatic breast (n = 32), pancreatic (n = 15), gastrointestinal (n = 16), lung (n = 12), ovarian (n = 2), or prostate cancers (n = 13), myeloma/lymphoma (n = 21), and cancers of unknown origin. Use of the study drug began within 4 weeks of the start of chemotherapy. Patients at moderate to high risk of bleeding were excluded (eg, patients with prolonged coagulation times or receiving antiplatelet therapy, bevacizumab, or other therapies with potential to cause bleeding). A total of 125 patients were randomized to receive once-daily doses of apixaban 5 mg (n = 32), 10 mg (n = 30), 20 mg (n = 33), or placebo (n = 30) in a double-blind manner for 12 weeks. In these groups, the number of clinically relevant bleeding episodes (main outcome) were one (3.1%), one (3.4%), four (12.5%), and one (3.4%). The corresponding number of major bleeding episodes was 0, 0, two, and one, respectively. There were no fatal bleeding episodes. No subjects in any of the apixaban groups and three patients in the placebo group (10.3%) developed symptomatic VTE. Three patients died (apixaban 5 mg, heart failure; placebo, heart failure and progressive cancer). There was a strong linear dose-response effect across the apixaban dose groups, with prothrombin fragments F1 and F2 decreasing by 1.9% (95% CI 0.7–3.1; P = 0.004) for each milligram of drug. In conclusion, apixaban 5 mg and 10 mg once daily were well tolerated in this study and associated with a low risk for VTE, thus supporting further study of apixaban in Phase III trials to prevent VTE in cancer patients receiving chemotherapy. These findings are limited due to the small sample size, the lack of screening for asymptomatic events, and the exclusion of patients at moderate to high bleeding risk. No further confirmatory studies are currently ongoing with apixaban in this setting.

VTE prophylaxis in medical patients

The ADOPT studyCitation75 was a double-blind, double-dummy, placebo-controlled trial in which acutely ill hospitalized medical patients were randomly assigned to receive apixaban orally at a dose of 2.5 mg twice daily for 30 days or subcutaneous enoxaparin at a dose of 40 mg once daily for 6–14 days. A total of 6528 subjects underwent randomization, of whom 632 (9.7%) had a history of cancer (active or past). The primary efficacy outcome (major VTE or death on day 30) occurred at a similar rate in the apixaban extended-course and enoxaparin short-term course groups (2.71% versus 3.06%; RR 0.87; 95% CI 0.62–1.23; P = 0.44). By day 30, major bleeding rates were low, but higher in the apixaban group than in the enoxaparin group (0.47% versus 0.19%; RR 2.58; 95% CI 1.02–7.24; P = 0.04). In conclusion, in medically ill patients, an extended course of thromboprophylaxis using apixaban was not superior to a shorter course using enoxaparin and was associated with significantly more major bleeding events than was enoxaparin. No subgroup analyses in patients with cancer are currently available.

Extended treatment of deep vein thrombosis and pulmonary embolism

The AMPLIFY-EXT studyCitation76 was a randomized, doubleblind trial that compared two doses of apixaban (2.5 mg and 5 mg twice daily) with placebo for one additional year in patients with VTE who had completed 6–12 months of anticoagulation therapy. A total of 2486 patients underwent randomization, of whom 2482 were included in the intention-to-treat analyses. Of these, 42 (1.7%) had active cancer at baseline, but no efficacy or safety data have been reported in this subpopulation. Symptomatic recurrent VTE occurred less often in patients who were receiving apixaban 2.5 mg (1.7%) or 5 mg (1.7%) than in patients who were receiving placebo (8.8%, RR of apixaban 2.5 mg versus placebo 0.19, 95% CI 0.11–0.33; RR of apixaban 5 mg versus placebo 0.20, 95% CI 0.11–0.34). The rates of major bleeding (main safety outcome) were very low, and were similar in the three groups (0.2% versus 0.1% versus 0.5%, ). The rates of clinically relevant bleeding were 3.2%, 4.3%, and 2.7% (RR of apixaban 2.5 mg versus placebo 1.20, 95% CI 0.69–2.10; RR of apixaban 5 mg versus placebo 1.62, 95% CI 0.96–2.73). In conclusion, extended anticoagulation with apixaban reduced the risk of recurrent VTE without significantly increasing the rate of major or clinically relevant bleeding.

Acute and long-term treatment of deep vein thrombosis and pulmonary embolism

A pivotal Phase III trial is ongoing to assess a single-drug approach with apixaban versus standard therapy for the acute and long-term treatment of VTE (AMPLIFY study, n = 4816 patients, www.clinicaltrials.gov ID, NCT00643201, ).

Edoxaban

Edoxaban (DU-176b, Lixiana®, Daiichi-Sankyo), the free form of edoxaban tosilate hydrate, is a novel oral direct FXa inhibitor.Citation77 In animal models, edoxaban inhibited venous thrombosis to an extent comparable with that of warfarin and enoxaparin, and the bleeding tendency was low.Citation78 Edoxaban is rapidly absorbed following oral administration, with a time to peak plasma concentrations of 1–2 hours.Citation79 Terminal elimination half-life ranges from 5.8 to 10.7 hours. Approximately 36%–45% of the dose administered is cleared through the kidneys (), and dose adjustment is needed in patients with renal impairment, low body weight, and/or older age.Citation79,Citation80 Edoxaban is mainly metabolized through hydrolysis, and CYP enzymes appear to have an insignificant role in its metabolism.Citation81 P-glycoprotein inhibitors are expected to increase the bioavailability of edoxaban by inhibition of P-glycoprotein in the intestine, and a reduced dose should be considered.Citation80

Edoxaban tosilate hydrate has been marketed in Japan since 2011 for the prevention of VTE in patients undergoing major orthopedic surgeryCitation80 on the basis of the results of the pivotal STARS studies.Citation82–Citation85 The compound has also shown promising results in a Phase IIb study in patients with nonvalvular atrial fibrillation.Citation86 A confirmatory study (ENGAGE AF-TIMI 48 study)Citation87 is underway in this indication (ClinicalTrials.gov ID, NCT00781391). An additional pivotal study is ongoing in the long-term treatment of deep vein thrombosis and pulmonary embolism (Edoxaban Hokusai-VTE study; n = 8250 patients, ). However, one of the exclusion criteria is patients with active cancer for whom long-term treatment with LMWH is anticipated (ClinicalTrials.gov ID, NCT00986154). The results are expected in 2013. No specific clinical studies in cancer patients are currently ongoing with edoxaban.

Betrixaban

Betrixaban (PRT-054021, Portola Pharmaceuticals, South San Francisco, CA) is an oral direct FXa inhibitor.Citation88 Betrixaban has demonstrated antithrombotic activity in animal models of thrombosis, and inhibited generation of thrombin in human blood at concentrations that may prevent VTE in humans.Citation89 Following oral administration, bioavailability is 34% and the half-life is 19 hours, which allows once-daily dosing. Betrixaban is not a substrate for major CYP enzymes,Citation90 but is a substrate for efflux proteins, including P-glycoprotein (). The major biotransformation pathway for betrixaban is hydrolysis and, to a lesser extent, demethylation.Citation90 It is excreted almost unchanged in bile (82%–89%) and urine (6%–13%).Citation91

The compound has shown promising results in dose-finding studies for VTE prophylaxis in patients undergoing total knee arthroplasty (EXPERT study)Citation91 and for stroke prevention in atrial fibrillation (EXPLORE-Xa),Citation92 but it has not been developed further in these indications. The Phase III pivotal APEX study is evaluating extended-duration oral betrixaban 80 mg once daily (for 28–42 days) with standard of care subcutaneous enoxaparin 40 mg once daily (for 6–14 days) for hospital and postdischarge prevention of VTE in acutely ill medical patients (ClinicalTrials.gov ID, NCT01583218). Concomitant cancer is not an exclusion criterion, and probably a subset of patients recruited will have cancer, in line with MAGELLANCitation63–Citation65 and ADOPT.Citation75 The global trial is expected to enroll approximately 6850 patients and is to be completed in December 2014 (). Portola is developing in parallel a universal antidote for Factor Xa inhibitor anticoagulants known as PRT064445, which is currently in Phase II in 144 healthy volunteers (ClinicalTrials.gov ID, NCT01758432). No specific clinical studies in patients with cancer are currently ongoing with betrixaban.

Novel direct oral thrombin inhibitors

Dabigatran etexilate

Dabigatran etexilate (BIBR 1048, Pradaxa®, Boehringer Ingelheim) is a small molecule prodrug.Citation93 After oral administration, dabigatran etexilate is rapidly absorbed and converted to its active metabolite, dabigatran (BIBR 953 ZW), by esterase-catalyzed hydrolysis in plasma and in the liver. Dabigatran is a potent, competitive, direct thrombin inhibitor. The absolute bioavailability of dabigatran following oral administration of dabigatran etexilate is approximately 6.5% ().Citation94 Maximum plasma concentrations are reached within 0.5 and 2 hours of oral administration,Citation94 but are delayed up to 6 hours if the oral dose is given early after surgery.Citation95 It is eliminated primarily unchanged in the urine (85%, ).Citation96 Dabigatran exposure is increased approximately 2.7-fold to 6-fold in moderate to severe renal insufficiency, respectively.Citation97 Dose adjustment is needed in moderate renal insufficiency, while it is contraindicated in severe renal insufficiency.Citation97 Concomitant treatment with dabigatran and quinidine, a potent P-glycoprotein inhibitor, is contraindicated, while caution should be exercised with other strong P-glycoprotein inhibitors like verapamil or clarithromycin. Potent P-glycoprotein inducers, such as rifampicin or St John’s wort (Hypericum perforatum), may reduce the systemic exposure of dabigatran.Citation97

Dabigatran etexilate is currently marketed in several regions for VTE prophylaxis after total hip replacement or total knee arthroplasty on the basis of four major clinical trials (RE-NOVATE I and II, RE-MODEL, and RE-MOBILIZE).Citation98–Citation101 It is also approved in several regions for stroke prevention in patients with atrial fibrillation based on the results of the RE-LY clinical trial.Citation102 The main results of the studies in the treatment of VTE (), some of them including data in patients with cancer, are discussed below.

Long-term treatment of VTE

RE-COVERCitation103 was a randomized, double-blind, noninferiority trial involving patients with acute VTE who were initially given parenteral anticoagulation therapy for a median of 9 days. The investigators compared oral dabigatran, administered at a dose of 150 mg twice daily, with warfarin dose-adjusted to achieve an INR of 2.0–3.0. The study randomized 2564 patients, of whom 2539 were included in the analysis (dabigatran, 1274; warfarin, 1265). Of these, 121 (4.8%) had active cancer at baseline. In total, 2.4% of patients (30/1274) on dabigatran and 2.1% (27/1265) on warfarin had recurrent symptomatic, objectively confirmed VTE and related deaths at 6 months (main study outcome, HR 1.10; 95% CI 0.65–1.84). Nonfatal pulmonary embolism occurred in 13 patients assigned to dabigatran and in seven patients assigned to warfarin (HR 1.85; 95% CI 0.74–4.64). Major bleeding rates were similar in the dabigatran and warfarin groups (1.6% versus 1.9%; HR 0.82; 95% CI 0.45–1.48), but episodes of any clinically relevant bleeding occurred less frequently with dabigatran than with warfarin (5.6% versus 8.8%; HR 0.63; 95% CI 0.47–0.84). The relative risk of recurrent VTE with dabigatran versus warfarin was similar among the 121 patients with cancer (RR 0.59; 95% CI 0.10–3.43) (). The relative risk of bleeding with dabigatran as compared with warfarin was similar among predefined subgroups,Citation103 but the specific results in cancer patients have not been published.

Table 6 Summary of results with new oral anticoagulants for prophylaxis or treatment of venous thromboembolism in cancer patients*

The twin study, RECOVER II,Citation104 included 2568 patients with acute VTE, and yielded very similar results to those of RECOVER (). No subgroup analysis is currently available. The authors concluded that dabigatran is noninferior to warfarin in the treatment of acute VTE and has a lower risk for bleeding.

Extended treatment of VTE

The RE-MEDY studyCitation105 compared extended treatment of VTE with dabigatran versus warfarin for a mean of 16 months in patients who had initially received 3–12 months of anticoagulant therapy. The study included 2856 patients, of whom 119 (4.2%) had active cancer. Dabigatran showed noninferior efficacy compared with warfarin with respect to recurrent VTE events (1.8% versus 1.3%; HR 1.44; 95% CI 0.78–2.64; P = 0.03 for the prespecified noninferiority margin). There were fewer clinically relevant bleeding episodes but more acute coronary syndromes with dabigatran than with warfarin (). Death rates were similar in both groups. In cancer patients, recurrent VTE rates were 3.3% (two of 60) in the dabigatran group and 1.7% (one of 59) in the warfarin group.

RE-SONATECitation105 investigated the extended treatment of VTE with dabigatran compared with placebo for 6 additional months in patients who had completed 6–18 months of anticoagulant therapy. Active cancer was an exclusion criterion. Dabigatran was superior to placebo in reducing the risk of recurrent VTE (0.4% versus 5.6%; HR 0.08; 95% CI 0.02–0.25), but was associated with an increase in clinically relevant bleeding (5.3% versus 1.8%; HR 2.92; 95% CI 1.52–5.60, ). Rates of cardiovascular events and deaths were similar in both groups. The benefit in reduction of recurrent VTE was maintained at one-year post- treatment follow-up (7.8% versus 11.6%; absolute risk difference −3.8%; 95% CI −7.1% to −0.5%; P = 0.0261).Citation106

Discussion

Currently, the two major areas of investigation in VTE prophylaxis and treatment of cancer patients are characterization of ambulatory medical patients on chemotherapy (type and stage of cancer and type of chemotherapy) who would benefit most from prophylactic anticoagulation in terms of survival, thrombotic and bleeding events, and quality of life on the one hand, and establishment of the optimal duration of anticoagulation in patients with VTE and cancer.

With respect to the new parenteral indirect FXa inhibitors, specific data in cancer patients are only available for semuloparin (). Data from the SAVE-ONCO studyCitation35–Citation37 in cancer patients on chemotherapy are promising, but have been insufficient to gain regulatory approval. Key unanswered questions relate to the effect of anticoagulant treatment on quality of life and whether such treatment affects tumor growth or dissemination. Most important, additional evidence is required as to which patients with cancer (ie, the type and stage of cancer) would benefit most, what is the magnitude of the survival benefit, and if there is a benefit in cancers that respond poorly to other therapies.Citation107

Once-weekly idrabiotaparinux dosing may potentially improve patient adherence in comparison with daily doses of a vitamin K antagonist.Citation108 Subgroup analyses in patients with deep vein thrombosis suggest a similar effect of the related compound, idraparinux, in patients with or without cancer.Citation45 However, its long half-life may be a drawback in cancer patients, who frequently undergo invasive diagnostic or therapeutic interventions that may require rapid reversal and rapid reintroduction of anticoagulation. The availability of an antidote (avidin) for idrabiotaparinux may help to alleviate worries about its long half-life.Citation48

The data available with the new oral agents from specific studies in cancer patients are limited to a small dose-finding trial with apixaban for thromboprophylaxis in patients undergoing chemotherapy, and using placebo as the comparator (ADVOCATE study, ).Citation74 Other thromboprophylaxis studies with new oral anticoagulants in medical patients, not focused on cancer patients, show a similar efficacy or the new anticoagulant in comparison with LMWH during active treatment and increased bleeding risk.Citation63,Citation74 In subgroup analyses of the MAGELLAN study, rivaroxaban showed a nonsignificant trend towards less efficacy compared with enoxaparin in patients with active cancer ().Citation65 The new oral anticoagulants may offer advantages over vitamin K antagonists in long-term and extended treatment of VTE, such as once-daily dosing and no need for routine monitoring of its anticoagulant activity. A small pooled analysis of the cancer patients included in the EINSTEIN-DVTCitation61 and EINSTEIN-PECitation62 studies suggests a similar efficacy and safety profile for rivaroxaban and warfarin in the long-term treatment of cancer patients with VTE (). On the other hand, the new oral anticoagulants may eliminate the need for daily injection of LMWH in the treatment of VTE in cancer patients, but further specific studies are needed to demonstrate that the new agents are as effective and safe as the standard of care in cancer patients (LMWH).

There are pharmacodynamic differences between the old and new compounds, which may result in differential effects in cancer patients. The antithrombotic effect of LMWH is well established, and some of their pleiotropic effects, like inhibition of cell-cell interaction by blocking cell adhesion molecules (selectins), inhibition of extracellular matrix protease heparanase, and inhibition of angiogenesis,Citation109 might translate into a survival benefit in patients with cancer.Citation107 All these pleiotropic effects are unlikely to be shown with the synthetic and more selective new anticoagulants.Citation110,Citation111

The optimal duration of treatment with an anticoagulant after a first episode of VTE has not been studied in patients with cancer. According to current guidelines, patients with permanent risk factors for VTE, such as those with active cancer or receiving chemotherapy, may benefit from extended duration of anticoagulant therapy beyond 3–6 months ().Citation15 Some studies with the new anticoagulants have assessed the issue of extending VTE treatment beyond 3–6 months in comparison with warfarinCitation105 or placebo,Citation61,Citation76,Citation105 but the percentage of patients with cancer included in these studies is very limited and further specific studies are needed.

With respect to safety, the lack of specific antidotes for the new oral anticoagulants may be problematic in patients with cancer, given that these patients are more likely to develop major bleeding complications during anticoagulant treatment than those without malignancy.Citation12 On the positive side, new oral anticoagulants may be potentially useful for anticoagulation in the management of patients with heparin-induced thrombocytopenia, a rare but serious complication of heparin treatment,Citation112 because they do not interact with PF4 in vitro,Citation113,Citation114 but further clinical studies are needed before recommendations can be made in this setting.

Conclusion

There are limited data available on the use of newer anticoagulants in cancer patients. Whether novel anticoagulants have a role in cancer patients is currently unknown. Further specific data in cancer patients are needed before these agents could be recommended for prophylaxis or treatment of VTE in this special population.

Disclosure

The contents of this review are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official view of their institutions or any other party. The authors declare no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- MackmanNTriggers, targets and treatments for thrombosisNature200845191491818288180

- NiederlaenderECauses of death in the EU. Statistics in focus. Population and social conditionsEurostat200610112

- BouillaudJBDe [’Obliteration des veines et de son influence sur la formation des hydropisies partielles: consideration sur la hydropisies passive et general (Obliteration of the veins and its influence on the formation of partial dropsies: consideration of the general and passive dropsies)Arch Gen Med18231188204 French

- TrousseauAPhlegmasia alba dolensBaillièreJBClinique Medicale de VHotel-Dieu de Paris Volume 32nd edParis, FranceJB Bailliere and Sons1865

- HeitJASilversteinMDMohrDNPettersonTMO’FallonWMMeltonLJIIIRisk factors for deep vein thrombosis and pulmonary embolism: a population-based case-control studyArch Intern Med200016080981510737280

- ChewHKWunTHarveyDZhouHWhiteRHIncidence of venous thromboembolism and its effect on survival among patients with common cancersArch Intern Med200616645846416505267

- SørensenHTSværkeCFarkasDKSuperficial and deep venous thrombosis, pulmonary embolism and subsequent risk of cancerEur J Cancer20124858659322129887

- PrandoniPFalangaAPiccioliACancer and venous thromboembolismLancet Oncol2005640141015925818

- FalangaADonatiMBPathogenesis of thrombosis in patients with malignancyInt JHematol20017313714411372723

- FalangaARicklesFRManagement of thrombohemorrhagic syndromes (THS) in hematologic malignanciesHematology Am Soc Hematol Educ Program200716517118024625

- NalluriSRChuDKeresztesRZhuXWuSRisk of venous thromboembolism with the angiogenesis inhibitor bevacizumab in cancer patients: a meta-analysisJAMA20083002277228519017914

- PrandoniPLensingAWPiccioliARecurrent venous thromboembolism and bleeding complications during anticoagulant treatment in patients with cancer and venous thrombosisBlood20021003484348812393647

- GouldMKGarciaDAWrenSMPrevention of VTE in nonorthopedic surgical patients: antithrombotic therapy and prevention of thrombosis, 9th ed. American College of Chest Physicians Evidence-Based Clinical Practice GuidelinesChest2012141Suppl 2e227Se277S22315263

- KahnSRLimWDunnASPrevention of VTE in nonsurgical patients: antithrombotic therapy and prevention of thrombosis. 9th ed. American College of Chest Physicians Evidence-Based Clinical Practice GuidelinesChest2012141Suppl 2e195Se226S22315261

- KearonCAklEAComerotaAJAntithrombotic therapy for VTE disease: antithrombotic therapy and prevention of thrombosis. 9th ed. American College of Chest Physicians Evidence-Based Clinical Practice GuidelinesChest2012141Suppl 2e419Se494S22315268

- FargeDDebourdeauPBeckersMInternational clinical practice guidelines for the treatment and prophylaxis of venous thromboembolism in patients with cancerJ Thromb Haemost201311567023217107

- MandalaMFalangaARoilaFManagement of venous thromboembolism [VTE] in cancer patients: ESMO Clinical Practice GuidelinesAnn Oncol201122Suppl 6vi85vi9221908511

- LymanGHKhoranaAAFalangaAAmerican Society of Clinical Oncology guideline: recommendations for venous thromboembolism prophylaxis and treatment in patients with cancerJ Clin Oncol2007255490550517968019

- National Comprehensive Cancer Network Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology Venous Thromboembolic Disease version 22011 Available from: http://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/f_guidelines.asp#supportiveAccessed October 23, 2012

- MannKGBrummelKButenasSWhat is all that thrombin for?J Thromb Haemost200311504151412871286

- DavieEWKulmanJDAn overview of the structure and function of thrombinSemin Thromb Hemost200632 Suppl 131516673262

- Siller-MatulaJMSchwameisMBlannAMannhalterCJilmaBThrombin as a multi-functional enzyme. Focus on in vitro and in vivo effectsThromb Haemost20111061020103321979864

- HuLLeeMCampbellWPerez-SolerRKarpatkinSRole of endogenous thrombin in tumor implantation, seeding, and spontaneous metastasisBlood20041042746275115265791

- DeFeoKHayesCChernickMRynJVGilmourSKUse of dabigatran etexilate to reduce breast cancer progressionCancer Biol Ther2010101001100820798593

- Gómez-OutesASuárez-GeaMLCalvo-RojasGDiscovery of anticoagulant drugs: a historical perspectiveCurr Drug Discov Technol201298310421838662

- ApostolakisSLipGYNovel oral anticoagulants: focus on the direct factor Xa inhibitor darexabanExpert Opin Investig Drugs20122110571064

- AhrensIPeterKLipGYBodeCDevelopment and clinical applications of novel oral anticoagulants. Part II. Drugs under clinical investigationDiscov Med20121344545022742650

- ViskovCJustMLauxVMourierPLorenzMDescription of the chemical and pharmacological characteristics of a new hemisynthetic ultra-low-molecular-weight heparin, AVE5026J Thromb Haemost200971143115119422447

- DubrucCKarimi-AnderesiNLunvenCZhangMGrossmannMPotgieterHPharmacokinetics of a new, ultra-low molecular weight heparin, semuloparin (AVE5026), in healthy subjects. Results from the first phase I studiesBlood2009114 Abstract 1073

- Gómez-OutesASuárez-GeaMLLecumberriRRochaEPozo-HernándezCVargas-CastrillónENew parenteral anticoagulants in developmentTher Adv Cardiovasc Dis20115335921045018

- EikelboomJWWeitzJINew anticoagulantsCirculation20101211523153220368532

- LassenMRFisherWMouretPAgnelliGSAVE InvestigatorsSemuloparin for prevention of venous thromboembolism after major orthopedic surgery: results from three randomized clinical trials, SAVE-HIP1, SAVE-HIP2 and SAVE-KNEEJ Thromb Haemost20121082283222429800

- FisherWAgnelliGGeorgeDExtended venous thromboembolism (VTE) prophylaxis after hip fracture surgery with the ultra-low-molecular-weight heparin (ULMWH) semuloparinPathophysiol Haemos Thromb2009/201037Suppl 1OC681

- TurpieAGGAgnelliGFisherWBenefit to-risk profile of the ultra-low-molecular weight heparin (ULMWH) semuloparin for prevention of venous thromboembolism (VTE): a meta-analysis of 3 major orthopaedic surgery studiesPathophysiol Haemos Thromb2009/201037Suppl 1OC332

- AgnelliGGeorgeDJKakkarAKSAVE-ONCO InvestigatorsSemuloparin for thromboprophylaxis in patients receiving chemotherapy for cancerN Engl J Med201236660160922335737

- Sanof Research and DevelopmentNDA 203213. Semuloparin SodiumOncologic Drugs Advisory Committee Meeting, June 20, 2012 Available from: http://www.fda.gov/downloads/AdvisoryCommittees/CommitteesMeetingMaterials/Drugs/OncologicDrugsAdvisoryCommittee/UCM308562.pdfAccessed December 29, 2012

- Food and Drug Administration Briefing Document. NDA 203213. Semuloparin sodiumOncologic Drugs Advisory Committee Meeting June 20, 2012 Available from: http://www.fda.gov/downloads/advisorycommittees/committeesmeetingmaterials/drugs/oncologicdrugsadvisorycommittee/ucm308561.pdfAccessed December 29, 2012

- KakkarAAgnelliGFisherWThe ultra-low-molecular-weight heparin semuloparin for prevention of venous thromboembolism in patients undergoing major abdominal surgeryAbstract 188 presented at the 52nd ASH Annual Meeting and ExpositionOrlando, FLDecember 4–7, 2010 Available from: https://ash.confex.com/ash/2010/webprogram/Paper31003.htmlAccessed December 29, 2012

- HerbertJMHéraultJPBernatABiochemical and pharmacological properties of SANORG 34006, a potent and long-acting synthetic pentasaccharideBlood199891419742059596667

- SaviPHeraultJPDuchaussoyPReversible biotinylated oligosaccharides. A new approach for a better management of anticoagulant therapyJ Thromb Haemost200861697170618647228

- MaQFareedJIdraparinux sodium. Sanof-AventisI Drugs200471028103415551178

- Veyrat-FolletCVivierNTrelluMDubrucCSanderinkGJThe pharmacokinetics of idraparinux, a long-acting indirect factor Xa inhibitor: population pharmacokinetic analysis from phase III clinical trialsJ Thromb Haemost2009755956519187079

- HarenbergJJörgIVukojevicYMikusGWeissCAnticoagulant effects of idraparinux after termination of therapy for prevention of recurrent venous thromboembolism: observations from the van Gogh trialsEur J Clin Pharmacol20086455556318283446

- BullerHRCohenATDavidsonBvan Gogh InvestigatorsIdraparinux versus standard therapy for venous thromboembolic diseaseN Engl J Med20073571094110417855670

- van DoormaalFFCohenATDavidsonBLIdraparinux versus standard therapy in the treatment of deep venous thrombosis in cancer patients: a subgroup analysis of the Van Gogh DVT trialThromb Haemost2010104869120508907

- BullerHRCohenATDavidsonBvan Gogh InvestigatorsExtended prophylaxis of venous thromboembolism with idraparinuxN Engl J Med20073571105111217855671

- HarenbergJVukojevicYMikusGJoergIWeissCLong elimination half-life of idraparinux may explain major bleeding and recurrent events of patients from the van Gogh trialsJ Thromb Haemost2008689089218315557

- PatyITrelluMDestorsJMCortezPBoëlleESanderinkGReversibility of the anti-FXa activity of idrabiotaparinux (biotinylated idraparinux) by intravenous avidin infusionJ Thromb Haemost2010872272920088937

- Equinox InvestigatorsEfficacy and safety of once weekly subcutaneous idrabiotaparinux in the treatment of patients with symptomatic deep venous thrombosisJ Thromb Haemost201199299

- BüllerHRGallusASPillionGPrinsMHRaskobGECassiopea InvestigatorsEnoxaparin followed by once-weekly idrabiotaparinux versus enoxaparin plus warfarin for patients with acute symptomatic pulmonary embolism: a randomised, double-blind, double-dummy, non-inferiority trialLancet201237912312922130488

- KubitzaDBeckaMVoithBZuehlsdorfMWensingGSafety, pharmacodynamics, and pharmacokinetics of single doses of BAY 59-7939, an oral, direct factor Xa inhibitorClin Pharmacol Ther20057841242116198660

- KubitzaDBeckaMWensingGVoithBZuehlsdorfMSafety, pharmacodynamics, and pharmacokinetics of BAY 59-7939 – an oral, direct Factor Xa inhibitor – after multiple dosing in healthy male subjectsEur J Clin Pharmacol20056187388016328318

- KubitzaDBeckaMRothAMueckWDose-escalation study of the pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of rivaroxaban in healthy elderly subjectsCurr Med Res Opin2008242757276518715524

- LangDFreudenbergerCWeinzCIn vitro metabolism of rivaroxaban, an oral, direct factor Xa inhibitor, in liver microsomes and hepatocytes of rats, dogs, and humansDrug Metab Dispos2009371046105519196846

- Xarelto®(rivaroxaban)Summary of product characteristics Available from: http://www.ema.europa.eu/docs/en_GB/document_library/EPAR_-_Product_Information/human/000944/WC500057108.pdfAccessed January 4, 2013

- ErikssonBIBorrisLCFriedmanRJRivaroxaban versus enoxaparin for thromboprophylaxis after hip arthroplastyN Engl J Med20083582765277518579811

- KakkarAKBrennerBDahlOEExtended duration rivaroxaban versus short-term enoxaparin for the prevention of venous thromboembolism after total hip arthroplasty: a double-blind, randomised controlled trialLancet2008372313918582928

- LassenMRAgenoWBorrisLCRivaroxaban versus enoxaparin for thromboprophylaxis after total knee arthroplastyN Engl J Med20083582776278618579812

- TurpieAGLassenMRDavidsonBLRivaroxaban versus enoxaparin for thromboprophylaxis after total knee arthroplasty (RECORD4): a randomised trialLancet20093731673168019411100

- PatelMRMahaffeyKWGargJRivaroxaban versus warfarin in nonvalvular atrial fibrillationN Engl J Med201136588389121830957

- BauersachsRBerkowitzSDBrennerBEINSTEIN InvestigatorsOral rivaroxaban for symptomatic venous thromboembolismN Engl J Med20103632499251021128814

- BüllerHRPrinsMHLensinAWEINSTEIN-PE InvestigatorsOral rivaroxaban for the treatment of symptomatic pulmonary embolismN Engl J Med20123661287129722449293

- CohenATSpiroTEBüllerHRExtended-duration rivaroxaban thromboprophylaxis in acutely ill medical patients: MAGELLAN study protocolJ Thromb Thrombolysis20113140741621359646

- CohenATSpiroTEBüllerHRRivaroxaban for thromboprophylaxis in acutely ill medical patientsN Engl J Med201336851352323388003

- CohenATSpiroTEBullerHRRivaroxaban versus enoxaparin for the prevention of venous thromboembolism in acutely ill medical patients: Magellan subgroup analysesJ Thromb Hemost20119Suppl 2 Abstract O-MO-034

- WongPCCrainEJXinBApixaban, an oral, direct and highly selective factor Xa inhibitor: in vitro, antithrombotic and antihemostatic studiesJ Thromb Haemost2008682082918315548

- Eliquis®(apixaban)Summary of product characteristics Available from: http://www.ema.europa.eu/docs/en_GB/document_library/EPAR_-_Product_Information/human/002148/WC500107728.pdfAccessed January 8, 2013

- WangLZhangDRaghavanNIn vitro assessment of metabolic drug-drug interaction potential of apixaban through cytochrome P450 phenotyping, inhibition, and induction studiesDrug Metab Dispos20103844845819940026

- RaghavanNFrostCEYuZApixaban metabolism and pharmacokinetics after oral administration to humansDrug Metab Dispos200937748118832478

- LassenMRRaskobGEGallusAPineoGChenDPortmanRJApixaban or enoxaparin for thromboprophylaxis after knee replacementN Engl J Med200936159460419657123

- LassenMRRaskobGEGallusAApixaban versus enoxaparin for thromboprophylaxis after knee replacement (ADVANCE-2): a randomised double-blind trialLancet201037580781520206776

- LassenMRGallusARaskobGEApixaban versus enoxaparin for thromboprophylaxis after hip replacementN Engl J Med20103632487249821175312

- GrangerCBAlexanderJHMcMurrayJJApixaban versus warfarin in patients with atrial fibrillationN Engl J Med201136598199221870978

- LevineMNGuCLiebmanHAA randomized phase II trial of apixaban for the prevention of thromboembolism in patients with metastatic cancerJ Thromb Haemost20121080781422409262

- GoldhaberSZLeizoroviczAKakkarAKApixaban versus enoxaparin for thromboprophylaxis in medically ill patientsN Engl J Med20113652167217722077144

- AgnelliGBullerHRCohenAApixaban for extended treatment of venous thromboembolismN Engl J Med201336869970823216615

- FurugohriTIsobeKHondaYDU-176b, a potent and orally active factor Xa inhibitor: in vitro and in vivo pharmacological profilesJ Thromb Haemost200861542154918624979

- MorishimaYHondaYKamisatoCComparison of antithrombotic and haemorrhagic effects of edoxaban, an oral direct factor Xa inhibitor, with warfarin and enoxaparin in ratsThromb Res201213051451922647432

- OgataKMendell-HararyJTachibanaMClinical safety, tolerability, pharmacokinetics, and pharmacodynamics of the novel factor Xa inhibitor edoxaban in healthy volunteersJ Clin Pharmacol20105074375320081065

- KawajiHIshiiMTamakiYSasakiKTakagiMEdoxaban for prevention of venous thromboembolism after major orthopedic surgeryOrthop Res Rev201245364

- BathalaMSMasumotoHOgumaTHeLLowrieCMendellJPharmacokinetics, biotransformation, and mass balance of edoxaban, a selective, direct factor Xa inhibitor, in humansDrug Metab Dispos2012402250225522936313

- FujiTFujitaSTachibanaSEfficacy and safety of edoxaban versus enoxaparin for the prevention of venous thromboembolism following total hip arthroplasty: STARS J-V trialBlood2010116 Abstract 3320

- FujiTWangCJFujitaSEdoxaban versus enoxaparin for thromboprophylaxis after total knee arthroplasty: the STARS E-3 TrialPathophysiol Haemost Thromb201037Suppl 1 Abstract A20

- FujitaSFujiTTachibanaSNakamuraKawaiYSafety and efficacy of edoxaban in patients undergoing hip fracture surgeryPathophysiol Haemost Thromb201037Suppl 1 Abstract A95

- FujiTFujitaSTachibanaSKawaiYEdoxaban versus enoxaparin for the prevention of venous thromboembolism: pooled analysis of venous thromboembolism and bleeding from STARS E-III and STARS J-VBlood2011118 Abstract 208

- WeitzJIConnollySJPatelIRandomised, parallel-group, multicentre, multinational phase 2 study comparing edoxaban, an oral factor Xa inhibitor, with warfarin for stroke prevention in patients with atrial fibrillationThromb Haemost201010463364120694273

- RuffCTGiuglianoRPAntmanEMEvaluation of the novel factor Xa inhibitor edoxaban compared with warfarin in patients with atrial fibrillation: design and rationale for the Effective aNticoaGulation with factor xA next GEneration in Atrial Fibrillation-Thrombolysis In Myocardial Infarction study 48 (ENGAGE AF-TIMI 48)Am Heart J201016063564120934556

- ZhangPHuangWWangLDiscovery of betrixaban (PRT054021), N-(5-chloropyridin-2-yl)-2-(4-(N,N-dimethylcarbamimidoyl)benzamido)-5-methoxybenz amide, a highly potent, selective, and orally efficacious factor Xa inhibitorBioorg Med Chem Lett2009192179218519297154

- AbeKSiuGEdwardsSAnimal models of thrombosis help predict the human therapeutic concentration of PRT54021, a potent oral factor Xa inhibitorBlood2006108 Abstract 901

- HutchaleelahaAYeCSongYLorenzTGretlerDLambingJLMetabolism and disposition of betrixaban and its lack of interaction with major CYP enzymesBlood2012120 Abstract 2266

- TurpieAGBauerKADavidsonBLA randomized evaluation of betrixaban, an oral factor Xa inhibitor, for prevention of thromboembolic events after total knee replacement (EXPERT)Thromb Haemost2009101687619132191

- EzekowitzMDA phase 2, randomized, parallel group, dose-finding, multicenter, multinational study of the safety, tolerability and pilot efficacy of three blinded doses of the oral factor Xa inhibitor betrixaban compared with open-label dose-adjusted warfarin in patients with non-valvular atrial fibrillation (EXPLORE-Xa)Presented at the American College of Cardiology 59th Annual Scientific SessionsAtlanta, GAMarch 14–16, 2010 Available from: http://assets.cardiosource.com/ezekowitz_explore1.ppt#636,1,EXPLORE-XaAccessed January 7, 2013

- MungallDBIBR-1048 Boehringer IngelheimCurr Opin Investig Drugs20023905907

- StangierJClinical pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of the oral direct thrombin inhibitor dabigatran etexilateClin Pharmacokinet20084728529518399711

- TrocónizIFTillmannCLiesenfeldKHSchäferHGStangierJPopulation pharmacokinetic analysis of the new oral thrombin inhibitor dabigatran etexilate (BIBR 1048) in patients undergoing primary elective total hip replacement surgeryJ Clin Pharmacol20074737138217322149

- BlechSEbnerTLudwig-SchwellingerEStangierJRothWThe metabolism and disposition of the oral direct thrombin inhibitor, dabigatran, in humansDrug Metab Dispos20083638639918006647

- Pradaxa®(dabigatran)Summary of product characteristics Available from: http://www.ema.europa.eu/docs/en_GB/document_library/EPAR_-_Product_Information/human/000829/WC500041059.pdfAccessed January 8, 2013

- ErikssonBIDahlOERosencherNDabigatran etexilate versus enoxaparin for prevention of venous thromboembolism after total hip replacement: a randomised, double-blind, non-inferiority trialLancet200737094995617869635

- ErikssonBIDahlOEHuoMHKurthAAHantelSHermanssonKOral dabigatran versus enoxaparin for thromboprophylaxis after primary total hip arthroplasty (RE-NOVATE II*). A randomised, double-blind, non-inferiority trialThromb Haemost201110572172921225098

- ErikssonBIDahlOERosencherNOral dabigatran etexilate versus subcutaneous enoxaparin for the prevention of venous thromboembolism after total knee replacement: the RE-MODEL randomized trialJ Thromb Haemost200752178218517764540

- GinsbergJSDavidsonBLCompPCRE-MOBILIZE Writing CommitteeOral thrombin inhibitor dabigatran etexilate vs North American enoxaparin regimen for prevention of venous thromboembolism after knee arthroplasty surgeryJ Arthroplasty2009241918534438

- ConnollySJEzekowitzMDYusufSDabigatran versus warfarin in patients with atrial fibrillationN Engl J Med20093611139115119717844

- SchulmanSKearonCKakkarAKDabigatran versus warfarin in the treatment of acute venous thromboembolismN Engl J Med20093612342235219966341

- SchulmanSKakkarAKSchellongSMA randomized trial of dabigatran versus warfarin in the treatment of acute venous thromboembolism (RE-COVER II)Blood2011118 Abstract 205

- SchulmanSKearonCKakkarAKExtended use of dabigatran, warfarin, or placebo in venous thromboembolismN Engl J Med201336870971823425163

- SchulmanSBaanstraDErikssonHBenefit of extended maintenance therapy for venous thromboembolism with dabigatran etexilate is maintained over 1 year of post-treatment follow-upBlood2012120 Abstract 21

- AklEASchünemannHJRoutine heparin for patients with cancer? One answer, more questionsN Engl J Med201236666166222335745

- PrinsMHLeguetPGiletHRoborel de ClimensAConvenience of the new long-acting anticoagulant idraparinux (IDRA) versus vitamin K antagonist (vitamin K antagonist) in patients with deep venous thrombosis (DVT)J Thromb Haemost20075Suppl 2 Abstract P-T-552

- BorsigLHeparin as an inhibitor of cancer progressionProg Mol Biol Transl Sci20109333534920807651

- StevensonJLChoiSHVarkiADifferential metastasis inhibition by clinically relevant levels of heparins-correlation with selectin inhibition, not antithrombotic activityClin Cancer Res20051119 Pt 17003701116203794

- KhoranaAASahniAAltlandODFrancisCWHeparin inhibition of endothelial cell proliferation and organization is dependent on molecular weightArterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol2003232110211512920044

- LinkinsLADansALMooresLKTreatment and prevention of heparin-induced thrombocytopenia: Antithrombotic Therapy and Prevention of Thrombosis, 9th ed. American College of Chest Physicians Evidence-Based Clinical Practice GuidelinesChest2012141Suppl 2e495Se530S22315270

- KrauelKHackbarthCFürllBGreinacherAHeparin-induced thrombocytopenia: in vitro studies on the interaction of dabigatran, rivaroxaban, and low-sulfated heparin, with platelet factor 4 and anti-PF4/heparin antibodiesBlood20121191248125522049520

- WalengaJMPrechelMJeskeWPRivaroxaban – an oral, direct Factor Xa inhibitor – has potential for the management of patients with heparin-induced thrombocytopeniaBr J Haematol2008143929918671707