Abstract

Several studies identify factors affecting increased length of stay (LOS) in patients with post-primary percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI). However, there has not been a review study that synthesizes these results. This study aimed to describe the duration of LOS and factors associated with increased LOS among patients with STEMI after PPCI. This study used scoping review using EBSCO-host Academic Search Complete, PubMed, Scopus, Taylor & Francis, and Google Scholar databases. The keywords used in English were “adults OR middle-aged” AND “length of stay OR hospital stay” AND “primary percutaneous coronary intervention OR PPCI” AND “myocardial infarction OR coronary infarction OR cardiovascular disease”. The inclusion criteria for articles were: the article was a full-text in English; the sample was STEMI patients who had undergone a PPCI procedure; and the article discussed the LOS. We found 13 articles discussing the duration and factors affecting LOS in patients post-PPCI. The duration of LOS was the fastest 48 hours, and the longest of LOS was 10.2 days. Factors influencing LOS are categorized into three predictors: low, moderate, and high. Post-procedure complications after PPCI was the most influential factors in increasing the LOS duration. Professional health workers, especially nurses, can identify various factors that can be modified to prevent complications and worsen disease prognosis to increase LOS efficiency.

Introduction

Acute Myocardial Infarction (AMI) is the main cause of death in the world. Globally, as many as 19.05 million people died from heart disease, including myocardial infarction, in 2020.Citation1 The most recent data shows that 1,522,669 AMI-related deaths were recorded in the United States during the last 10 years from 2012 to 2022.Citation1 Meanwhile, in Indonesia, as many as 1.5% or 15 out of 1000 Indonesians suffer from heart disease, including myocardial infarction.Citation2 This mortality rate is expected to continue to increase to 24.2 million people in 2030.Citation3

ST-segment elevation Myocardial infarction (STEMI) indicates of total coronary artery occlusion.Citation4 The diagnosis of STEMI is established if there is a complaint of acute angina pectoris accompanied by persistent ST-segment elevation in two adjacent leads.Citation4,Citation5 This situation requires revascularization as soon as possible to restore blood flow and myocardial reperfusion.Citation5 System delays to reperfusion correlate with higher mortality and morbidity rates.Citation6 Currently, primary percutaneous coronary intervention (PPCI) is the most effective acute management strategy for STEMI patients and is superior to fibrinolytic therapy.Citation5 The purpose of PPCI is to restore normal blood flow to the patient’s heart by opening blocked coronary arteries.Citation4

Although PPCI has been considered a safe general procedure, consideration of the severity of MI and further monitoring after the procedure is essential for optimal results.Citation7,Citation8 Previous studies have proven that the severity of MI contributes to the success of the PPCI procedure.Citation7 Factors that may influence MI severity include location and size of infarction, coronary artery occlusion level, and time from symptom onset to appropriate treatment.Citation9 Patients with more severe MI may be at higher risk of experiencing post-PPCI complications such as bleeding or heart attack so that this will have an impact on increasing the length of stay (LOS) and mortality rate.Citation10,Citation11

LOS is an essential factor in determining the patient outcomes, especially for those suffering from severe conditions such as STEMI.Citation12 LOS is the number of days the patient is in the hospital (counted from the patient’s admission until the patient is discharged or goes home), which is also an essential criterion in evaluating the efficiency of patient care management.Citation13,Citation14 LOS can significantly impact a patient’s recovery, as well as the overall cost of treatment.Citation15 Moreover, reducing LOS has been associated with decreased risks of opportunistic infections and medication side effects and with improved treatment outcomes and lower mortality rates.Citation16 An increase in LOS results in higher morbidity and mortality in hospitals.Citation12,Citation17 Previous cohort studies suggest that LOS in-hospital is independently associated with an increased burden of comorbidities in PCI patients.Citation18

Several studies in developed and developing countries report an increase in LOS in post-PPCI. Patients are usually discharged three days after treatment for a STEMI with an uncomplicated PPCI.Citation8 A study in Iran said that almost the majority (47%) of post-PPCI patients had LOS of 3–6.Citation19 In addition, a study in China showed that post-PPCI patients had an average LOS of more than 7 days.Citation13,Citation20 Similarly, studies conducted in developed countries such as the UK and USA also reported that the average LOS in post-PPCI patients was more than 4 days.Citation21–24 Differences in the duration of LOS in patients after PPCI can be influenced by various factors apart from the similarity of disease diagnoses. A previous study said age, hypertension, chronic kidney diseases, and diabetes mellitus were the determining factors for increasing LOS in post-PPCI patients.Citation19 Also, the risk of LOS for more than six days was seen in subjects with post-procedure complications, admission problems, and primary comorbidities.Citation13 Therefore, paying more attention to predictor of LOS is essential because of its important role in saving hospital costs and improving overall health outcomes.

To date, there have been quite several studies that have found various predictors that influence LOS increases in post-PPCI patients. However, based on our literature search, there have been no reviewed studies that have systematically explored and synthesized these results in the post-PPCI patient population. Several previous reviews focused only on re-hospitalization,Citation25 factors that lead to depression,Citation26 and focused on mortality and readmission.Citation27 Previous studies have characterized a diverse population rather than focusing on post-PPCI patients. Considering the limitations of previous reviews, this study will focus more on post-PPCI patients. PPCI is now established as the reference treatment for the management of STEMI.Citation5 However, there are still studies showing differences in LOS in patients who undergo it. It is important to identify causal factors so that they can provide input to anticipate increasing LOS in these patients, and make PPCI effective as the main treatment referral.Citation28 Therefore, this study aims to identify the duration of LOS and factors associated with increased LOS among patients with STEMI after PPCI.

Materials and Methods

Design

The design used in this literature review is a scoping review. Scoping review is a flexible methodological technique for exploring new, rapidly developing topics.Citation29 This design has a more comprehensive conceptual range so that it can explain a variety of relevant study results. The framework of scoping review consists of 5 core stages, namely identifying research questions, identifying relevant study results, selecting studies, mapping data, compiling, summarizing and reporting results.Citation29

Eligibility Criteria

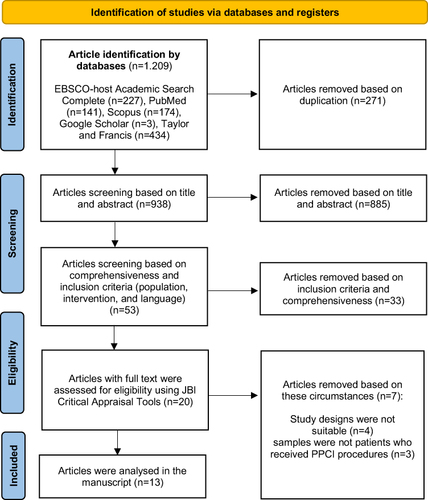

The article selection process in this review was carried out by six reviewers based on the PRISMA Extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR) checklist and explained in the form of a chart (see ). Research questions and eligibility criteria for research articles using the PCC approach.

Figure 1 PRISMA flow diagram.

P (Population): adults and myocardial infarction patients

C (Concept): length of stay (LOS)

C (Context): primary percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI)

Secondary research, such as literature reviews and editorials were excluded from this review. The inclusion criteria were a full text in English; focused on adults who were defined as people aged more than 18 years, the sample was STEMI patients after PPCI; and the article discussed LOS. We do not limit the year of publication because we want to comprehensively identify the factors that influence LOS so that the results of the study can be generalized better.

Data Collection and Analysis

Search Strategy

The article searching process has been carried out using five primary databases: EBSCO-host Academic Search Complete, PubMed, Scopus, Taylor & Francis, and Google Scholar. The keywords used in English were “adults OR middle aged” AND ‘length of stay OR hospital stay’ AND ‘primary percutaneous coronary intervention OR PPCI’ AND ‘myocardial infarction OR coronary infarction OR cardiovascular disease’. For each term verified by MeSH (Medical Subject Headings) synonyms were used to retrieve all possible relevant articles. The author uses the Boolean operators “AND” and “OR” to cut or expand the search results for various forms of words.

Study Selection

Three independent authors selected the studies that met the eligibility criteria. The article was removed based on duplication in the initial stage using the reference manager application. The authors also evaluate the relevance of the title and abstract after any duplicate article is removed. At the final stage, authors review all eligible full text articles according to inclusion and exclusion criteria. Then, the authors checked each article against the Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI) critical appraisal checklist.Citation31 Following the assessment, we eliminated any study with a JBI score <60%. The final determination of articles which is included or excluded in this review was carried out by the second and third authors provide a decision if there is a discrepancy in the selection results.

Data Extraction and Analysis

Data extraction in this study was carried out using the tabular form to describe all results related to the topics discussed. The table contains data related to author, year, country, research design, sample age, average and category of LOS, and findings of the results. The main points of discussion can be identified and grouped entirely for further discussion. This data extraction table was created to make it easier for the authors to describe the review results.

All included studies were primary studies with cohort and cross-sectional designs. Therefore, data analysis was carried out thematically using an exploratory, descriptive approach. The data analyzing process begins with the identification and presentation of the data obtained in tabular form. All authors analyzed and explained each finding based on factors that affect LOS in STEMI patients after PPCI therapy. The categorization of developed and developing countries refers to the website of the world bank.Citation32 In addition, in the predictor category the authors divide it into three classifications based on the odds ratio (OR) value. It is categorized as low if the OR value is less than or equal to 2, moderate if the OR value is more than 2 to 4, and high if the OR value is more than 4. Then, if the study does not include an OR value then it is considered to be in the uncategorized.

Results

Study Selection

1.029 articles were successfully identified in the initial search and totalled 758 after duplication was removed. Elimination based on titles and abstracts resulted in 53 articles which were then selected based on an analysis of full-text articles. As a results, the authors included 13 articles in this review as shown by the PRISMA flowchart (see ).

Study Characteristics

The results of this review show that the articles analyzed were cohort studies (n=12) and cross-sectional studies (n=1). Based on the results, the shortest and most prolonged LOS were 48 hours to 10.2 days. Most of the articles analyzed in this review were conducted in developed countries (see ). All participants analyzed were myocardial infarction patients (n=858.115) who had undergone PPCI with an average age of 50 to 75.47 years. Several studies have also reported (>90%) patients who achieved full perfusion of infarct vessels with the final thrombolytic myocardial infarction (TIMI) flow in grade 3 after a PPCI procedure.Citation13,Citation19,Citation22,Citation23,Citation33

Table 1 Characteristics of Study

Factors Associated with Increased Length of Stay

Factors related to increased of LOS in STEMI patients after PPCI are divided into several categories (see ). Factors affecting increased LOS are age >68 years, gender, BMI >24.22 kg/m2, complications during treatment, comorbid diseases, Killip class >1, smoking, infarction area, and problem at admission.

Table 2 Factors Associated with Increased LOS

These factors are divided into three categories based on the OR values, namely low (0 to ≤2), moderate (>2 to 4), and high (>4) (see ). The higher the OR value, the independent factor becomes the most influential factor. This review shows that the predictors in the low category are age (> 68 years), gender, BMI >24.22, comorbid disease (Diabetes Mellitus (DM), hypertension (HTN), CKD), current smoker, and anterior STEMI. In addition, those included in the moderate category are complications (angiographic failure, bleeding, AKI), and also left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF). Then, the predictors included in the high category are complications (Vascular complication and Post-procedure complications), heart failure (HF), Killip class >1, and problems at admission. Post-procedure complications were the most influential factors in increasing the LOS duration (OR: 9.12; 95% CI: 7.22–11.53; p<0.001). The predictors that are not categorized are delirium, liver cirrhosis and multivessel disease.

Discussion

This scoping review describes LOS duration and its associated factors among patients with STEMI who have undergone PPCI. Overall, the results showed that the duration of LOS in this review was the fastest 48 hours, and the longest of LOS was 10.2 days. 10 factors can affect the LOS in STEMI patients after primary PCI, namely age, gender, BMI, complications during treatment, comorbid diseases, Killip class >1, smoking, infarction area, and problems at admission. Then, the authors classify these factors into three predictor categories based on OR values, namely low, moderate, and high.

The factors that most influence the increase in LOS after PPCI in this review are included in the high category (see ). Post-procedure complications were the most influential factors in increasing the LOS duration.Citation34 Regarding the incidence of post-PPCI complications, pulmonary edema is the most common while cardiogenic shock (CS) is the most rare complication.Citation34 Although rare, the occurrence of CS causes patients to experience a decrease in LVEF and has an impact on having a poor prognosis and high risk of death.Citation19,Citation22,Citation23,Citation33 Hemodynamic deterioration, occurrence of multi-organ dysfunction and development of a systemic inflammatory response play a major role in the increased LOS and mortality of patients with CS complications post-PPCI.Citation22,Citation33

Several studies also reported that vascular complications were the most common post-PPCI complications.Citation10,Citation22,Citation37 The high frequency of bleeding events after surgery is the highest risk related to complications post PCI in the first 24 to 48 hours.Citation25 This bleeding can be caused by PVC.Citation10 The incidence of PCI-related PVCs could be due to hypertension, use of dual antiplatelet drugs and heparin, introducer sheath size and Glycoprotein IIb/IIIa during PCI procedures.Citation38 In addition, HF is the only comorbid disease that is a predictor in the high category. People with a history of HF are also at high risk of experiencing a longer duration of hospitalization.Citation13 Prior HF as a predictor of fatality may contribute to adverse outcomes and a high risk of death in patients with AMI.Citation13,Citation37 This is associated with ischemic sequelae that persist after cardiac arrest.Citation39

Another predictor that is included in the high category is the Killip class.Citation10,Citation13,Citation28 A study in Turkey showed that patients with Killip class >1 had a 4.68-fold risk of having prolonged LOS.Citation10 Previous studies also said that most participants with Killip class >1 had LOS of more than 7 days.Citation13 The higher the Killip classification, the worse the patient’s prognosis, affecting the LOS in the hospital.Citation10 One of the reasons for the increase in Killip class is the problems that occur during patient admission. Problems on admission are also among the most influential predictors of increasing LOS.Citation34 In this review, problems at admission are not related to delays in PPCI actions but can be a factor in increasing LOS when PPCI has been carried out. These problems include increased blood pressure, low LVEF, and decreased glomerular filtration rate (GFR).Citation19 Patients with problems during admission have a LOS of 3–6 days. STEMI patients who experience problems during admission will have an impact on the severity and prognosis, so they will certainly be at risk of experiencing a longer LOS after PPCI.Citation34

Complications that are included in the predictors in the moderate category in this review are an angiographic failure, bleeding, and AKI.Citation10,Citation22,Citation24,Citation35,Citation37 Patients who are complicated by angiographic failure can have a prolonged LOS after PPCI is performed.Citation10 Previous studies found an independent association between ≥6 days of LOS with angiographic failure.Citation10 Angiographic failure (low post-procedure TIMI flow) is one of the Zwolle index criteria that defines a patient as being at high risk.Citation40 This tool is helpful for systematically evaluating patients for safe early discharge and optimizing clinical outcomes after undergoing PPCI.Citation41 In addition, AKI is the most common complication when patients experience bleeding and CS.Citation33,Citation37,Citation42 Bleeding events will certainly affect the perfusion to the kidney and cause the patient to experience AKI.Citation37 AKI is an independent prognostic factor for extended hospital stay and mortality among STEMI patients complicated by CS and treated with PPCI.Citation42 Previous studies said that the mortality rate was found to be 61.3% in this population.Citation43 The incidence of CS post-PPCI can be identified through its independent predictors, namely TIMsI post PCI, glucose levels, plasma lactate, and blood urea nitrogen levels.Citation43

Several predictors are included in the low category that affects LOS in patients after PPCI. Age is an independent factor that is a predictor of LOS.Citation10,Citation13,Citation19,Citation22,Citation33,Citation37 Previous studies said that the elderly with an average age of >68 years have a longer LOS.Citation10 Pathophysiological changes such as increased calcification, worse endothelial function, and a history of the cardiac disease contribute to the higher adverse event rate among the elderly undergoing PCI.Citation44 Another factor that influences LOS is gender.Citation10,Citation22 This review found that both male and females’ patients are at risk for prolonged LOS. However, some studies said females are more at risk.Citation10,Citation33,Citation37 Females have a 1.5 to 4 times higher risk of vascular complications than men and an increased risk of bleeding at the femoral artery access after PPCI (70.4%).Citation45 Pathophysiologically, female are more likely to develop thrombosis caused by endothelial erosion.Citation46 This can affect homeostatic processes in modulating metabolism, proliferation, permeability, response to inflammatory stimuli and apoptosis.Citation47 So that, in the end, affects the development of plaque and the characteristics of lesions that have the potential to rupture and result in longer LOS in female patients after PPCI.Citation47

In another low-category predictor, the risk of prolonged LOS is also experienced by obese patients and smoker. Previous studies show that increased BMI was in line with prolonged LOS.Citation13,Citation34 Patients with extreme BMI (<18.5 and >40kg/m2) are also at increased risk of adverse outcomes after PCI.Citation48 Patients post-PPCI who were treated for more than 7 days had an average BMI of 24.22 kg/m2.Citation13 There is a relationship between obesity and coronary atherosclerosis, with hemodynamic, metabolic, and inflammatory factors as well as oxidative stress contributing to the development of cardiovascular disease in obese patients.Citation48 This study also found that STEMI patients who smoked had a longer LOS than nonsmokers.Citation10,Citation23,Citation37 Smoking affects faster atherosclerosis, increased blood coagulability, and greater platelet reactivity, which will cause physiological effects and the risk of complications during treatment.Citation49 Previous studies have shown that most of the participants who smoke (59.9%) have LOS of more than 6 days.Citation10 Similarly, previous studies said smoking is associated with a worse prognosis after PPCI.Citation50

Our findings showed that almost all comorbid diseases are included in the category of low predictors of affecting LOS after PPCI. DM, HTN, and CKD are the most commonly reported primary comorbidities and affect the longer of LOS (>5 days).Citation10,Citation19,Citation33,Citation37 People with DM are at increased risk of coronary atherosclerosis, plaque burden, and inducing endothelial dysfunction.Citation10,Citation19,Citation33,Citation37 Other studies have shown that duration of LOS >6 days is more common in STEMI patients with a history of HTN.Citation10,Citation13,Citation19 This can be caused by several factors, such as endothelial damage, atherosclerosis, left ventricular hypertrophy, and arrhythmias that will impact the LOS.Citation13 STEMI patients with CKD also experience long hospitalization days (>7 days) due to procedural complications after PPCI.Citation19,Citation37 The existence of vascular complications, including bleeding, occlusion site access, loss of distal pulse, dissection and pseudoaneurysm, will undoubtedly have an impact on LOS in patients with CKD.Citation51

Our findings suggest that the location of infarction also determines the LOS post-PPCI patients.Citation10,Citation23 Patients with an anterior infarction is at greater risk of experiencing a longer LOS.Citation10,Citation23 In addition, the left anterior descending (LAD) area has been associated with poorer epicardial and microvascular reperfusion. LAD infarction carries a higher myocardial risk, results in more severe systolic dysfunction, and is more likely to embolize distal atherothrombotic material after PCI, all potential mechanisms of poorer final myocardial reperfusion that result in longer LOS.Citation52

Uncategorized predictors, including delirium, liver cirrhosis, and multi-vessel disease have been reported by several studies to influence clinical outcomes and prolong the duration of LOS in patients after PPCI.Citation20,Citation21,Citation28 Complications such as delirium are known to be more common in older patients (>60 years) due to the effects of anesthesia and their sensitivity to non-anesthetic drugs.Citation53 Another complication that often occurs post-PPCI is vascular problems, especially in elderly patients.Citation54 This supports another study results which reported that patients with other comorbid conditions such as liver cirrhosis and multivessel disease are also at a much higher risk of experiencing vascular complications due to significant bleeding related to thrombocytopenia after PPCI and resulted in an extension of LOS.Citation21,Citation28 Differences in the clinical outcome of each patient are very likely to be found in prolonging LOS depending on the type of comorbidities and complications experienced by the patient before or after the PPCI procedure.

The outcomes of each PPCI patient were highly heterogeneous. Thus, assessing the risk stratification of each patient, especially after undergoing PPCI is very important.Citation55 The commonly used tool to assess the success of PCI is the TIMI grade flow.Citation55 However, the results of this review indicate that only a few studies have reported the results of TIMI of flow post-PPCI.Citation13,Citation19,Citation22,Citation23,Citation33 In fact, evaluating the TIMI score after PCI indicates the success of the action, which is closely related to the prognosis and severity of the patient, so it influences LOS.Citation55 Also, assessing the patient’s risk stratification is essential for further clinical and therapeutic decision-making.

In this review, the predictor of LOS among patients with STEMI after PCI is multifactorial. The author observes that almost every sample in each article reviewed has more than one factor, accompanied by the coexistence of other risk factors such as age, gender, comorbid disease, and other factors. Therefore, efforts must be made to improve the care of STEMI patients after PPCI by providing early discharge education earlier. Early discharge programs within 16–72 hours of STEMI patients after PCI are considered low risk, proven safe, and may be undertaken to reduce re-hospitalization rates and LOS.Citation56,Citation57 In addition, the use of artificial intelligence (AI) in the last decades has been highly recommended and has shown its effectiveness in the management of patients with coronary artery disease (CAD) and atrial fibrillation (AF).Citation58 AI systems can be used to examine large amounts of patient data to detect risk factors for AF and assess the potential for developing the disease. Thus, the application of AI in the world of health is beneficial for health professionals in choosing the appropriate treatment based on patient needs.Citation58

Limitations of This Study

The limitation of this scoping review is that it is difficult for the authors to categorize predictors of LOS into short-term and long-term because the studies analyzed did not compare these two factors. However, the authors divide it into three categories (low, moderate, and high) based on the OR value of each predictor. In addition, most of the studies analyzed did not identify a TIMI grade flow score or other risk stratification tool, so the review results cannot be generalized regarding risk stratification in this population. Then, the results of this review show that most of the articles analyzed in this review were conducted in developed countries, so similar research needs to be conducted in developing countries so that the results of this review can be generalized better.

Conclusion

This study shows that 13 articles from five databases discuss the description of LOS duration and the factors influencing LOS in post-PPCI patients. In this study, the shortest LOS duration was the fastest 48 hours, and the longest was 10.2 days. The factors affecting LOS in this population are classified into three categories: low, moderate, and high. Post-procedure complications (pulmonary oedema and CS) were the most influential predictor of increased LOS in PPCI patients. Many factors related to LOS are essential considerations for health workers, especially nurses, in evaluating and re-optimizing the quality of care for STEMI patients after PPCI. Nurses can identify various modifiable factors to prevent complications and worsen disease prognosis to increase LOS efficiency and care costs while in the hospital.

Disclosure

The authors had no conflicts of interest in this research.

Acknowledgments

All authors thank to Universitas Padjadjaran, Bandung, West Java, Indonesia, who has facilitated the database for us in this study.

References

- American Heart Association. 2023 heart disease and stroke statistics update fact sheet; 2023. Available from: https://professional.heart.org/en/science-news/heart-disease-and-stroke-statistics-2023-update. Accessed Jun 2, 2023.

- Ministry of Health Republic of Indonesia. Hasil Riset Kesehatan Dasar Tahun 2018 (Results of Basic Health Research 2018). Health Dev Res Agency. 2018;53:1689–1699.

- World Health Organization (WHO). Cardiovascular diseases (CVDs); 2021. Available from: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/cardiovascular-diseases-(cvds). Accessed Jun 2, 2023.

- Association of Indonesian Cardiovascular Specialists. Guidelines for the Management of Acute Coronary Syndromes. 3. Editio, PERKI. 2015. Centra Communications

- Lawton JS, Tamis-Holland JE, Bangalore S, et al. 2021 ACC/AHA/SCAI Guideline for Coronary Artery Revascularization: a Report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Joint Committee on Clinical Practice Guidelines. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2022;79(2):e21–129. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2021.09.006

- Levine GN, Bates ER, Blankenship JC, et al. 2015 ACC/AHA/SCAI focused update on primary percutaneous coronary intervention for patients with ST-elevation myocardial infarctionAn update of the 2011 ACCF/AHA/SCAI guideline for percutaneous coronary intervention and the 2013 ACCF/AHA guideline for the. Circulation. 2016;133(11):1135–1147. doi:10.1161/CIR.0000000000000336

- McCartney PJ, Berry C. Redefining successful primary PCI. Eur Heart J Cardiovasc Imaging. 2019;20(2):133–135. doi:10.1093/ehjci/jey159

- Dalal F, Dalal HM, Voukalis C, Gandhi MM. Management of patients after primary percutaneous coronary intervention for myocardial infarction. BMJ. 2017;358:1–10.

- Ojha N, Dhamoon A Myocardial Infarction Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2022. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK537076/. Accessed Jun 2, 2023.

- Isik T, Ayhan E, Uluganyan M, Gunaydin ZY, Uyarel H. Predictors of Prolonged In-Hospital Stay after Primary Percutaneous Coronary Intervention for ST-Elevation Myocardial Infarction. Angiology. 2016;67(8):756–761. doi:10.1177/0003319715617075

- Merriweather N, Sulzbach-Hoke LM. Managing risk of complications at femoral vascular access sites in percutaneous coronary intervention. Crit Care Nurse. 2012;32(5):16–29. doi:10.4037/ccn2012123

- Seto AH, Shroff A, Abu-Fadel M, et al. Length of stay following percutaneous coronary intervention: an expert consensus document update from the society for cardiovascular angiography and interventions. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv off J Soc Card Angiogr Interv. 2018;92(4):717–731. doi:10.1002/ccd.27637

- Lv J, Zhao Q, Yang J, et al. Length of Stay and Short-Term Outcomes in Patients with ST-Segment Elevation Myocardial Infarction After Primary Percutaneous Coronary Intervention: insights from the China Acute Myocardial Infarction Registry. Int J Gen Med. 2021;14:5981–5991. doi:10.2147/IJGM.S330379

- Arefian H, Hagel S, Fischer D, et al. Estimating extra length of stay due to healthcare-associated infections before and after implementation of a hospital-wide infection control program. PLoS One. 2019;14(5):e0217159. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0217159

- Yip W, Fu H, Chen AT, et al. 10 years of health-care reform in China: progress and gaps in universal health coverage. Lancet. 2019;394(10204):1192–1204. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(19)32136-1

- Siddiqui MKR, Rahman MM, Ahmed B, et al. Impact of body mass index on in-hospital length of stay after percutaneous coronary interventions. Cardiovasc J. 2020;13(1):19–26. doi:10.3329/cardio.v13i1.50560

- Hannan EL, Zhong Y, Cozzens K, et al. Short-term Deaths After Percutaneous Coronary Intervention Discharge: prevalence, Risk Factors, and Hospital Risk-Adjusted Mortality. J Soc Cardiovasc Angiogr Interv. 2023;2(2):100559. doi:10.1016/j.jscai.2022.100559

- Potts J, Kwok CS, Ensor J, et al. Temporal Changes in Co-Morbidity Burden in Patients Having Percutaneous Coronary Intervention and Impact on Prognosis. Am J Cardiol. 2018;122(5):712–722. doi:10.1016/j.amjcard.2018.05.003

- Mirbolouk F, Salari A, Gholipour M. The factors related to hospitalization period in patients with acute myocardial infarction treated after primary percutaneous coronary intervention. ARYA Atheroscler. 2020;16(3):115–122. doi:10.22122/arya.v16i3.1915

- Li S, Zhang X-H, Zhou G-D, Wang J-F. Delirium after primary percutaneous coronary intervention in aged individuals with acute ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction: a retrospective study. Exp Ther Med. 2019;17(5):3807–3813. doi:10.3892/etm.2019.7398

- Alqahtani F, Balla S, AlHajji M, et al. Temporal trends in the utilization and outcomes of percutaneous coronary interventions in patients with liver cirrhosis. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv. 2020;96(4):802–810. doi:10.1002/ccd.28593

- Swaminathan RV, Rao SV, McCoy LA, et al. Hospital length of stay and clinical outcomes in older STEMI patients after primary PCI: a report from the National Cardiovascular Data Registry. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2015;65(12):1161–1171. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2015.01.028

- Karamasis GV, Russhard P, Al Janabi F. Peri-procedural ST segment resolution during Primary Percutaneous Coronary Intervention (PPCI) for acute myocardial infarction: predictors and clinical consequences. J Electrocardiol. 2018;51(2):224–229. doi:10.1016/j.jelectrocard.2017.09.011

- Patel NJ, Pau D, Nalluri N, et al. Temporal Trends, Predictors, and Outcomes of In-Hospital Gastrointestinal Bleeding Associated With Percutaneous Coronary Intervention. Am J Cardiol. 2016;118(8):1150–1157. doi:10.1016/j.amjcard.2016.07.025

- Kwok CS, Narain A, Pacha HM, et al. Readmissions to Hospital After Percutaneous Coronary Intervention: a Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Factors Associated with Readmissions. Cardiovasc Revascularization Med. 2020;21(3):375–391. doi:10.1016/j.carrev.2019.05.016

- Doi-Kanno M, Fukahori H. Predictors of depression in patients diagnosed with myocardial infarction after undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention: a literature review. J Med Dent Sci. 2016;63(2–3):37–43. doi:10.11480/jmds.630301

- Lan T, Liao YH, Zhang J, et al. Mortality and readmission rates after heart failure: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Ther Clin Risk Manag. 2021;17:1307–1320. doi:10.2147/TCRM.S340587

- Karabulut A, Cakmak M, Uzunlar B, Bilici A. What is the optimal length of stay in hospital for ST elevation myocardial infarction treated with primary percutaneous coronary intervention? Cardiol J. 2011;18(4):378–384.

- Peterson J, Pearce PF, Ferguson LA, Langford CA. Understanding scoping reviews: definition, purpose, and process. J Am Assoc Nurse Pract. 2017;29(1):12–16. doi:10.1002/2327-6924.12380

- Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ. 2021;372:n71. doi: 10.1136/bmj.n71

- Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI). JBI’s critical appraisal tools. Joanna Briggs Institute; 2022. Available from: https://jbi.global/critical-appraisal-tools. Accessed Jun 2, 2023.

- The World Bank. Countries and Economies; 2023. Available from.: https://data.worldbank.org/country. Accessed Jun 2, 2023.

- Chin CT, Weintraub WS, Dai D, et al. Trends and predictors of length of stay after primary percutaneous coronary intervention: a report from the CathPCI Registry. Am Heart J. 2011;162(6):1052–1061. doi:10.1016/j.ahj.2011.09.008

- Mirbolouk F, Salari A, Gholipour M, et al. The factors related to hospitalization period in patients with acute myocardial infarction treated after primary percutaneous coronary intervention. ARYA Atheroscler. 2020;16(3):1–8. doi:10.22122/arya.v16i1.1941

- Chua SK, Liao CS, Hung HF, et al. Gastrointestinal bleeding and outcomes after percutaneous coronary intervention for ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction. Am J Crit Care. 2011;20(3):218–225. doi:10.4037/ajcc2011683

- Schellings DAAM, Ottervanger JP, Van’T Hof AWJ, et al. Predictors and importance of prolonged hospital stay after primary PCI for ST elevation myocardial infarction. Coron Artery Dis. 2011;22(7):458–462. doi:10.1097/MCA.0b013e3283495d5f

- Velagapudi P, Kolte D, Ather K, et al. Temporal Trends and Factors Associated With Prolonged Length of Stay in Patients With ST-Elevation Myocardial Infarction Undergoing Primary Percutaneous Coronary Intervention. Am J Cardiol. 2018;122(2):185–191. doi:10.1016/j.amjcard.2018.03.365

- Koskinas KC, Räber L, Zanchin T, et al. Clinical Impact of Gastrointestinal Bleeding in Patients Undergoing Percutaneous Coronary Interventions. Circ Cardiovasc Interv. 2015;8(5):1–9. doi:10.1161/CIRCINTERVENTIONS.114.002053

- Radisauskas R, Kirvaitiene J, Bernotiene G, Virviciutė D, Ustinaviciene R, Tamosiunas A. Long-term survival after acute myocardial infarction in Lithuania during transitional period (1996–2015): data from population-based Kaunas Ischemic heart disease register. Medicina. 2019;55(7):357. doi:10.3390/medicina55070357

- De Luca G, Suryapranata H, Hof AWJ, et al. Prognostic assessment of patients with acute myocardial infarction treated with primary angioplasty: implications for early discharge. Circulation. 2004;109(22):2737–2743. doi:10.1161/01.CIR.0000131765.73959.87

- Parr CJ, Avery L, Hiebert B, Liu S, Minhas K, Ducas J. Using the Zwolle Risk Score at Time of Coronary Angiography to Triage Patients With ST-Elevation Myocardial Infarction Following Primary Percutaneous Coronary Intervention or Thrombolysis. J Am Heart Assoc. 2022;11(4). doi:10.1161/JAHA.121.024759

- Hayıroğlu Mİ, Bozbeyoglu E, Yıldırımtürk Ö, Tekkeşin Aİ, Pehlivanoğlu S. Effect of acute kidney injury on long-term mortality in patients with ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction complicated by cardiogenic shock who underwent primary percutaneous coronary intervention in a high-volume tertiary center. Turk Kardiyol Dern Ars. 2020;48(1):1–9. doi:10.5543/tkda.2019.84401

- Hayıroğlu Mİ, Keskin M, Uzun AO, et al. Predictors of In-Hospital Mortality in Patients With ST-Segment Elevation Myocardial Infarction Complicated With Cardiogenic Shock. Hear Lung Circ. 2019;28(2):237–244. doi:10.1016/j.hlc.2017.10.023

- Bauer T, Zeymer U. Impact of age on outcomes of percutaneous coronary intervention in acute coronary syndromes patients. Interv Cardiol. 2010;2(3):319–325. doi:10.2217/ica.10.27

- Spirito A, Gragnano F, Corpataux N, et al. Sex-based differences in bleeding risk after percutaneous coronary intervention and implications for the academic research consortium high bleeding risk criteria. J Am Heart Assoc. 2021;10(12). doi:10.1161/JAHA.121.021965

- Heer T, Hochadel M, Schmidt K, et al. Sex Differences in Percutaneous Coronary Intervention-Insights From the Coronary Angiography and PCI Registry of the German Society of Cardiology. J Am Heart Assoc. 2017;6(3):1–10. doi:10.1161/JAHA.116.004972

- Stone PH, Maehara A, Coskun AU, et al. Role of Low Endothelial Shear Stress and Plaque Characteristics in the Prediction of Nonculprit Major Adverse Cardiac Events: the PROSPECT Study. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging. 2018;11(3):462–471. doi:10.1016/j.jcmg.2017.01.031

- Patlolla SH, Gurumurthy G, Sundaragiri PR, Cheungpasitporn W, Vallabhajosyula S. Body mass index and in-hospital management and outcomes of acute myocardial infarction. Med. 2021;57(9):87.

- Wu HP, Jan SL, Chang SL, Huang CC, Lin MJ. Correlation Between Smoking Paradox and Heart Rhythm Outcomes in Patients With Coronary Artery Disease Receiving Percutaneous Coronary Intervention. Front Cardiovasc Med. 2022;9:1–8.

- Redfors B, Furer A, Selker HP, et al. Effect of Smoking on Outcomes of Primary PCI in Patients With STEMI. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2020;75(15):1743–1754. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2020.02.045

- Ismail MD, Jalalonmuhali M, Azhari Z, et al. Outcomes of STEMI patients with chronic kidney disease treated with percutaneous coronary intervention: the Malaysian National Cardiovascular Disease Database - Percutaneous Coronary Intervention (NCVD-PCI) registry data from 2007 to 2014. BMC Cardiovasc Disord. 2018;18(1):184. doi:10.1186/s12872-018-0919-9

- Caixeta A, Lansky AJ, Mehran R, et al. Predictors of suboptimal TIMI flow after primary angioplasty for acute myocardial infarction: results from the HORIZONS-AMI trial. Euro Intervention J Eur Collab with Work Gr Interv Cardiol Eur Soc Cardiol. 2013;9(2):220–227.

- Salluh JIF, Wang H, Schneider EB, et al. Outcome of delirium in critically ill patients: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ. 2015;350:1–10. doi:10.1136/bmj.h2538

- Fleg JL, Forman DE, Berra K, et al. Secondary prevention of atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease in older adults: a scientific statement from the American heart association. Circulation. 2013;128(22):2422–2446. doi:10.1161/01.cir.0000436752.99896.22

- Talreja K, Sheikh K, Rahman A, et al. Outcomes of Primary Percutaneous Coronary Intervention in Patients With a Thrombolysis in Myocardial Infarction Score of Five or Higher. Cureus. 2020;12(7). doi:10.7759/cureus.9356

- Azzalini L, Solé E, Sans J, et al. Feasibility and safety of an early discharge strategy after low-risk acute myocardial infarction treated with primary percutaneous coronary intervention: the EDAMI pilot trial. Cardiology. 2015;130(2):120–129. doi:10.1159/000368890

- Satilmisoglu MH, Gorgulu S, Aksu HU, et al. Safety of Early Discharge after Primary Percutaneous Coronary Intervention. Am J Cardiol. 2016;117(12):1911–1916. doi:10.1016/j.amjcard.2016.03.039

- Ecg A, Ecg AA. The Role of Artificial Intelligence in Coronary Artery Disease and Atrial Fibrillation. Balk Med J. 2023;40(3):151–152. doi:10.4274/balkanmedj.galenos.2023.06042023