Abstract

Anti-tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α) therapy has re-defined our treatment paradigms in managing patients with Crohn’s disease (CD) and ulcerative colitis. Although the ACCENT studies showed proven efficacy in the induction and maintenance of disease remission in adult patients with moderate to severe CD, the pediatric experience was instrumental in bringing forth the notion of “top-down” therapy to improve overall clinical response while reducing the risk of complications resulting from long-standing active disease. Infliximab has proven efficacy in the induction and maintenance of disease remission in children and adolescents with CD. In an open-labeled study of 112 pediatric patients with moderate to severe CD, 58% achieved clinical remission on induction of infliximab (5 mg/kg) therapy. Among those patients who achieved disease remission, 56% maintained disease remission on maintenance (5 mg/kg every 8 weeks) therapy. Longitudinal follow-up studies have also shown that responsiveness to infliximab therapy also correlates well with reduced rates of hospitalization, and surgery for complication of long-standing active disease, including stricture and fistulae formation. Moreover, these children have also been shown to improve overall growth while maintaining an effective disease remission. The pediatric experience has been instructive in suggesting that the early introduction of anti-TNF-α therapy may perhaps alter the natural history of CD in children, an observation that has stimulated a great deal of interest among gastroenterologists who care for adult patients with CD.

Keywords:

Introduction

Crohn’s disease (CD) and ulcerative colitis are chronic inflammatory intestinal disorders affecting 1.7 million people in North America.Citation1 Recent studies have shown an increasing incidence of CD in children, and an overall prevalence of 10% to 25% of all patients with inflammatory bowel disease (IBD).Citation2,Citation3 CD is characterized by patchy transmural inflammation involving any segment of the gastrointestinal tract from the mouth to the anus. Patients will typically show recurrent clinical exacerbations marked by symptoms of abdominal pain, diarrhea, and rectal bleeding, alternating with episodes of quiescent disease. Children often manifest constitutional signs of weight loss, growth failure and pubertal delay that may in part be secondary to extensive proximal small bowel disease of increased severity. Moreover, pediatric CD is often associated with extra intestinal manifestations, including arthritis, episcleritis, uveitis and erythema nodosum.Citation1

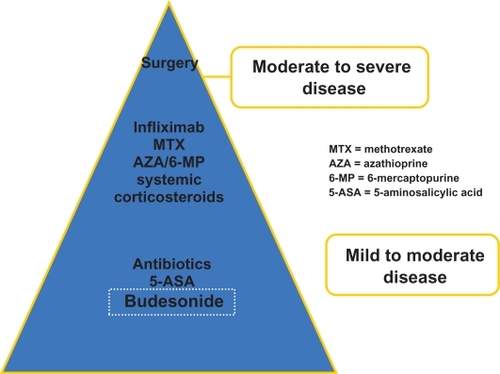

Although the principal goal of therapy is to induce and maintain an effective disease remission, the intestinal mucosa will often show ongoing inflammation that contributes to frequent relapses and less than favorable maintenance of clinical remission. Since CD may progress from intestinal inflammation to strictures and penetrating disease, including fistulas and abscess formation, mucosal healing has become a primary treatment objective. Since delayed puberty and growth failure is seen in 15% to 40% of pediatric patients with CD,Citation4 achieving normal growth and development also represents an important end-point to therapy. The ultimate goal is to achieve and sustain an effective disease remission that avoids complications associated with long-standing and unremitting disease. To achieve this clinical objective is of paramount importance in order to improve patient quality of life, and avoid psychological complications, including anxiety, and depression. Given the myriad of potential therapies available to treat patients with CD, it has become increasingly important to select those medications with the most favorable benefit risk ratio that will minimize the overall need for corticosteroids ().

Non-biological therapy

Enteral nutrition has proven efficacy in inducing disease remission in children with active CD,Citation5 as well as preventing disease relapse in 60% to 75% of patients within a year.Citation6,Citation7 Although enteral nutrition is effective in inducing disease remission and in reversing micronutrient deficiencies, these treatment formulas are unpalatable and often require nasogastric or gastrostomy tube placement. Typically, adolescent patients are non-adherent to the prolonged implementation of nutritional therapy. They often object to the placement of these feeding tubes or the exclusivity of enteral nutritional therapy during periods of quiescent disease.Citation5–Citation7

Thomsen and coworkers showed in a double blind multicenter study of 182 adults with CD that mesalamine was able to induce remission in 45%, 42% and 36% of patients with mild to moderate disease at the end of 8 weeks, 12 weeks and 16 weeks, respectively.Citation8 However, de Franchis and coworkers showed that once patients achieved disease remission on mesalamine, less than 50% of patients were able to sustain disease remission after one year of maintenance therapy.Citation9

Although studies have shown that corticosteroids are effective in inducing remission in patients with active CD,Citation10 not all patients respond favorably. And among those patients that respond to induction corticosteroids, 40% to 68% of patients will relapse within a year, while up to 36% of patients will develop corticosteroid dependency.Citation11–Citation14 This observation is also underscored by the detrimental impact of long-term corticosteroid use on patient growth and development.

Immunosuppressant drugs, including methotrexate, azathioprine (AZA, and 6-mercaptopurine (6-MP) are all effective in maintain disease remission in 40% to 65% of patients with corticosteroid-dependent moderate to severe CD.Citation15–Citation18

Biological therapy

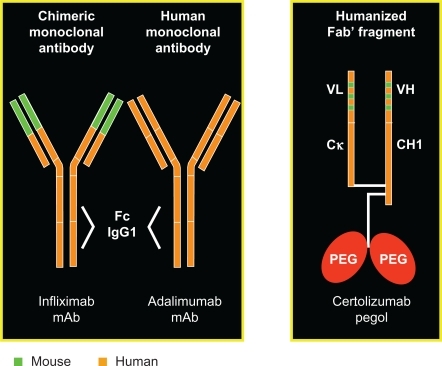

In comparison, the biological agents used in CD include: the anti-tumor necrosis factor alpha(TNF-α) agents infliximab, adalimumab and certolizumab pegol () and anti-adhesion molecule drugs. All of these biological agents have been shown to be effective in children with CD. Herein, our focus will be on the role of infliximab in treating pediatric CD.

TNF-α

Over the last several years, our understanding of the pathogenesis of CD has improved remarkably with the development of several animal models. Indeed, the pro-inflammatory cytokine TNF-α is known to play an important role in CD,Citation19 and has led to the development of several novel treatment strategies, including infliximab. TNF-α can transmit signals between immune cells leading to inflammation, thrombosis and fibrinolysis. Various stimuli, including bacterial endotoxin, radiation and viral antigens can bring on the release of secretory TNF-α from monocytes, macrophages and T-cell lymphocytes. As a potent pro-inflammatory cytokine, TNF-α must be firmly regulated; and failure to do so, allows for an unmediated inflammatory response.Citation20 In patients with CD, TNF-α is highly localized to the intestinal mucosa and lumen. Indeed, high concentrations have been measured in the lamina propria of the bowel of patients with CDCitation21 and increased concentration of TNF has also been found in the stool of children with CD.Citation22 At the level of the mucosa, TNF-α recruits circulating inflammatory cells to the intestinal tissue, inducing tissue edema, coagulation activation through thrombin activation and granuloma formation. The migration of neutrophils is further facilitated through the increased expression of adhesion molecules and IL-8 by endothelial cells. TNF-α is pivotal in the formation of granulomas, one of the histological hallmarks of CD. Through its up-regulation of monocyte chemo-attractant protein-1, monocytes are recruited into the site of gramulomatous inflammation. CD4 T-cell lymphocytes are the probable source for TNF-α production, as well as other cytokines involved in the so-called TH1 response, including interferon-α at the site of granulomas.

Infliximab

Infliximab is a chimeric IgG-1 monoclonal antibody with a high specificity for TNF-α. It induces apoptosis of TNF-producing cells, and promotes antibody dependent and complement dependent cytotoxicity.Citation23–Citation25 It has been shown to decrease histologic and endoscopic disease activity and in inducing and maintaining remission in patients with active CD. ACCENT I was a multicenter randomized double-blind international trial studying retreatment and remission maintenance in adult patients with CD treated with infliximab. Patients in this study were divided into 3 groups: patients given a single 5 mg/kg infusion, patients given 5 mg/kg every 8 weeks, and patients given 10 mg/kg every 8 weeks for maintenance of remission. After 54 weeks, the initial clinical response was maintained in only 17% of patients in the single dose group compared to 43% of patients maintained on 5 mg/kg every 8 weeks and 53% of patients maintained on 10 mg/kg every 8 weeks. In addition, successful steroid-tapering was seen in only 9% of patients in the single dose group compared to 28% in the 5 mg/kg every 8 weeks group, and 32% of patients in the 10 mg/kg every 8 weeks group.Citation26

It has been the practice in many institutions, including our own to initiate maintenance anti-TNF-α therapy in patients that have shown clear refractoriness to either long-term 6-MP or AZA therapy. All of the studies, including ACCENT, CHARM and PRECISE have not shown any potential role of combining anti-TNF-α with anti-metabolite therapy. Moreover, the increasing concern of hepatic T-cell lymphoma has led many physicians to consider discontinuing either 6-MP or AZA with the introduction of biological therapy.Citation27 Although all anti-TNFα therapies have antigenic properties, those patients on infliximab therapy are most vulnerable. The concurrent use of immunosuppressive therapy has in the past been shown by Rutgeerts and coworkers to maintain a favorable clinical response to maintenance infliximab therapy, presumably due to the prevention of human anti-chimeric antibody (HACA) antibody formation. In that study, 75% (12/16) of patients on concurrent 6-MP maintained a favorable clinical response, compared to 50% (9/18) on no concurrent immunosuppressive therapy.Citation28 In the ACCENT 1 study, only 18% of the patients on neither concurrent prednisone nor immunosuppressive drug therapy developed HACA, compared to just 10% of patients on concurrent azathioprine or methotrexate therapy.Citation26 The therapeutic benefit of concurrent immunosuppressive therapy is generally considered marginal and is felt to not outweigh the associated increased risk of hepatic T-cell lymphomas, a malignancy that is universally lethal in the pediatric patient population.Citation27 Moreover, both adalimumab and certolizumab have proven efficacy in salvaging those patients who develop either a partial responsiveness or intolerance to infliximab therapy.Citation28 As a result, the purported benefit is not felt to outweigh the increased risk for malignancy.

Other drug safety issues with infliximab include the development of anti-neutrophil antibodies and anti-double stranded DNA in 34% and 56% of patients on maintenance infliximab therapy, respectively. Furthermore, the long-term risk in developing systemic lupus is unknown, and may have an increased bearing on the African-American population. Other noteworthy long-term safety issues include the risk of super-infection (32%) and the risk of tuberculosis.Citation11

Adalimumab

The immunogenicity of infliximab has led to the development of other less immunogenic TNF inhibitory agents, including adalimumab and certolizumab. Adalimumab (fully human anti-TNF) has recently received approval for the treatment of active CD. Several studies have shown adalimimab to be superior to placebo for inducing and maintaining remission. It has also been shown to spare corticosteroids and salvage those patients with CD recalcitrant to infliximab therapy with an excellent safety profile. Unlike infliximab, adalimumab is prescribed as a subcutaneous injection every 2 weeks as a maintenance therapy.Citation28,Citation29

Infliximab use in children

Studies evaluating the safety and efficacy of infliximab in children were first reported in several non-randomized studies.Citation30–Citation34 These initial studies showed that the response and remission rates (both partial and complete) were far superior compared to conventional therapy. Interestingly, its efficacy in children appeared to be higher than in adult.Citation31,Citation32

In a multicenter, open-label, dose-blinded trial (n = 21), Baldassano and coworkers demonstrated the efficacy and safety of a single infusion of infliximab in the treatment of pediatric CD. During the 12-week duration of the study, 100% achieved a clinical response and 48% achieved clinical remission, with significant improvements in the pediatric CD activity index (PCDAI), modified CDAI, erythrocyte sedimentation rate, and other outcome variables of interest. There were no infusion reactions in any of the patients and it was suggested that infliximab may be safe and effective as short-term therapy of medically refractory moderate to severe CD.Citation35 A prospective study published by Cezard and coworkers also explored the efficacy and toxicity of infliximab in children with severe CD. Twenty-one children (median age 15, range 13 to 17) were treated with infliximab with an induction sequence of 5 mg/kg at 0, 15, and 45 days. Nineteen children were in complete remission (defined as Harvey-Bradshaw index (HBI) <4) on day 45. 14/21 patients had stopped taking steroids at 3 months, and all had stopped parenteral nutrition. All perianal fistulas (n = 12) were also closed by day 90 and the drug appeared to be well tolerated.Citation36

Much evidence at present comes from retrospective analysis of children treated with infliximab, often as a rescue medication. In a retrospective study in children and adolescents with either corticosteroid dependent or resistant CD, patients were randomized to receive 1 to 3 infusions of infliximab (5 mg/kg/dose) over a 12-week period. The mean daily prednisone dosages decreased significantly in all the patients (P < 0.01) studied. A significant initial improvement (as assessed by a significant decline in PCDAI value) was noted in all subjects (P < 0.0001). Interestingly, over the subsequent 8-week period, 8 of 19 treated subjects had worsening of symptoms.Citation37 Lamireau and coworkers described yet another retrospective study in 88 children and adolescents (median age: 14, range: 3.3 to 17.9) treated with infliximab for active disease (66%) and/or fistulas (42%) that were refractory to corticosteroids (70%), and/or other immunosuppressive (82%) agents, and/or parenteral nutrition (20%). Patients received a median of 4 (1 to 17) infusions of 5 mg/kg of infliximab during a median time period of 4 months (1 to 17 months). From day 0 to day 90, the Harvey-Bradshaw score decreased from 7.5 to 2.8 (P < 0.001), with a significant decrease in both C-reactive protein and ESR (P < 0.001). At day 90 after the first infusion of infliximab, 49% of patients had symptom improvement, 29% were in remission; 53% of patients could be weaned off of corticosteroids and 92% off of parenteral nutrition.Citation38 The authors in both these studies concluded that treatment with infliximab was well tolerated and effective in most children and adolescents with CD refractory to conventional immunosuppressive therapy. No serious events were noted in any of these studies.

The Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approval for the use of infliximab therapy in pediatric CD was based on the results of the much publicized REACH clinical study, a randomized, multicenter, open-label study to evaluate the safety and efficacy of anti-TNF-α antibody in pediatric subjects with moderate to severe CD. A total of 112 pediatric patients (ages 6 to 17 years) with moderate to severe CD who took part in this study received infliximab at 5 mg/kg at week 0, 2 and 6. Patients who showed symptom improvement, or response, were then randomized to 2 groups and received infliximab every 8 or 12 weeks for almost 1 year. A concurrent immunomodulator was also required. At week 10, 88% patients showed response (defined as decrease from baseline in the PCDAI score ≥15 points; total score ≤30) and 58% patients achieved clinical remission (defined as PCDAI score ≤10 points). At week 54, 63% and 56% patients receiving infliximab every 8 weeks were in clinical response and clinical remission, respectively, compared with 33% and 23% patients receiving treatment every 12 weeks (P = 0.002 and P < 0.001, respectively). The data from this important prospective trial thus suggested that infliximab is not only highly effective in inducing clinical response and remission but also in maintenance of remission, more so with an 8-week dosing compared with every 12-week dosing.Citation39 The same research consortium also found infliximab to be an effective therapy in children with perianal disease, including patients with perianal fistula,Citation40 and in prolonging the withdrawal of corticosteroids over a 3-year follow-up period.Citation41 Similar observations have also been made in an European study in children with CD. In that study, children on an on-demand treatment schedule were more-likely to experience a relapse (92%) when compared to patients on 2-month infusion schedule (23%).Citation42

Immunogenicity

HACA is the common side effect of infliximab infusion. The antibody is as a result of murine component of chimeric infliximab. However, adalimumab a fully human anti-TNF-α drug also has similar side-effects. In the REACH study, 2.9% (3 patients) developed HACA when compared to 35% on other trials.Citation39,Citation43–Citation45 This could be explained by patients in the REACH study receiving concurrent immunosuppressive medication. Seventy-seven percent of patients in the REACH had inconclusive HACA results. HACA causes infusion reactions (acute and delayed), shortened response and also loss of response. Risk factors for development of HACA are single and episodic infusion, female gender, long gap between first and second infusion, and previous infusion reaction. Studies suggest that it can me minimized by giving maintained therapy, a concomitant immunosuppressive agent, and corticosteroid.Citation44,Citation45

Acute infusion reaction occurs in 11% to 8% patients and at 2.5% to 5.3% per infusion depending on the dosing method and concomitant treatment.Citation39,Citation46–Citation48 Patients develop pruritus, chest pain, nausea, headache, and flushing within 24 hours. Antihistamines and/or corticosteroids do not prevent the infusion reaction. However, infusion reaction can be controlled by slow infusion, along with administration of antihistamine and corticosteroids. It is our general practice to pre-medicate those patients susceptible to infliximab-induced infusion reactions with hydrocortisone therapy.Citation48

Delayed infusion reaction is very rare (0.7% to 3%). Patients presents after 4 to 9 days with back pain, myalgia, arthralgia, and skin rash.Citation46,Citation47 It is seen after the second or third infusion dose and usually responds to corticosteroid therapy.

Infliximab therapies often induce formation of anti nuclear antibody and anti double standard antibody.Citation49 However these antibodies are not of any clinical significance as studies suggest that no pediatric patients have developed drug-induced systemic lupus or organ damage.

Infections

Infliximab causes decreased levels of polymorph nuclear cells and T-cell lymphocytes specifically at mucosal site. This results in increased risk of infectious with bacteria, virus and fungi. Active infection is a contraindication for infliximab use. Also, live vaccines are contraindicated as there is an increase risk of serious infection. Every patient has to undergo a screening test for tuberculosis, as multiple studies suggest reactivation of latent tuberculosis.Citation50,Citation51

The risk of infection is 3.8% to 8% and the upper respiratory tract is commonly affected.Citation26,Citation52 In the REACH study, the incidence rate of upper respiratory tract infection was 35.8% and 32.0% in patients receiving infliximab every 8 weeks and every 12 weeks, respectively.Citation39 Overall infection rate was high (73.6%) among the first group patients than the later group (38.0%). But serious infection occurred at the same rate in both the groups (5.7% to 8%). In a study of adult patients with CD, Colombel and coworkers treated 500 patients with infliximab, 41 (8.2%) of whom developed infection. Among these 41 patients, 15 had serious infection (2 fatal sepsis, 8 pneumonia, 1 severe viral gastroenteritis, 2 abdominal abscess, 1 arm cellulitis, 1 histoplasmosis).Citation53 Other studies also suggest the occurrence of Listeria monocytogenes meningitis, cutaneous Tinea, shingles, and herpes zoster.Citation45,Citation54 One report also suggests reactivation of hepatitis B in 3 patients diagnosed with chronic hepatitis B on treatment with infliximab.Citation55

Malignancy

In a prospective study of 20 patients, 28% developed reactivation of Epstein-Barr virus (EBV). However, EBV PCR level returned to normal after 6 months of discontinuing infliximab.Citation56 In a study of 6290 adult patients on maintenance infliximab therapy, there was no increased risk of malignancy in the infliximab group compared to patients on conventional therapy.Citation57 In a multi-center matched-pair trial, the incidence rate of malignancy was 2.2% (9 patients) in the CD group and 1.7% (7 patients) in the non-CD group after a follow-up of 4.5 years.Citation58 Meena and coworkers first reported a case of hepatosplenic T-cell lymphoma in a 17-year-old female CD patient treated with infliximab and 6-MP.Citation27 Nine more cases of hepatic T-cell lymphoma have been reported in IBD patients treated with infliximab and 6-MP/AZA.Citation59 However there is no case report of an IBD patient developing hepatic T-cell lymphoma on infliximab alone.

Summary

The arsenal of biological therapies is increasing. A large multi-centered pediatric study is now investigating the use of adalimumab in children with CD. Furthermore, the FDA approval of certolizumab, a novel pegylated anti-TNF therapy, is expected soon. The pediatrician will soon be faced with the dilemma of which medications to use, in either the more traditional step-up or top-down approach. Indeed, there is a growing tendency to consider biological drugs in lieu of more traditional therapies, as discussed above. While genotype–phenotype correlations may allow clinicians to predict certain more aggressive forms of CD, future studies are still needed to provide an evidenced-based approach to drug therapy.

Disclosures

Dr Cuffari is a consultant for, and receives research support from, UCB, the manufacturer of certolizumab.

References

- CuffariCInflammatory bowel disease in children: A pediatrician’s perspectiveMinerva Pediatr200658213915716835574

- KugathasanSJuddRHHoffmannRGEpidemiologic and clinical characteristics of children with newly diagnosed inflammatory bowel disease in wisconsin: A statewide population-based studyJ Pediatr2003143452553114571234

- HildebrandHFinkelYGrahnquistLChanging pattern of paediatric inflammatory bowel disease in northern stockholm 1990–2001Gut200352101432143412970135

- GriffithsAMNguyenPSmithCGrowth and clinical course of children with crohn’s diseaseGut19933479399438344582

- HiwatashiNEnteral nutrition for crohn’s disease in JapanDis Colon Rectum19974010 SupplS48S539378012

- GriffithsAMOhlssonAShermanPMMeta-analysis of enteral nutrition as a primary treatment of active crohn’s diseaseGastroenterology19951084105610677698572

- Gonzalez-HuixFde LeonRFernandez-BanaresFPolymeric enteral diets as primary treatment of active crohn’s disease: A prospective steroid controlled trialGut19933467787828314510

- ThomsenOOCortotAJewellDA comparison of budesonide and mesalamine for active crohn’s disease. international budesonide-mesalamine study groupN Engl J Med199833963703749691103

- de FranchisROmodeiPRanziTControlled trial of oral 5-amin-osalicylic acid for the prevention of early relapse in crohn’s diseaseAliment Pharmacol Ther19971158458529354191

- LevineAWeizmanZBroideEA comparison of budesonide and prednisone for the treatment of active pediatric crohn diseaseJ Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr200336224825212548062

- MunkholmPLangholzEDavidsenMFrequency of glucocorticoid resistance and dependency in crohn’s diseaseGut19943533603628150347

- GreenbergGRFeaganBGMartinFOral budesonide for active crohn’s disease. canadian inflammatory bowel disease study groupN Engl J Med1994331138368418078529

- RutgeertsPLofbergRMalchowHA comparison of budesonide with prednisolone for active crohn’s diseaseN Engl J Med1994331138428458078530

- CampieriMFergusonADoeWOral budesonide is as effective as oral prednisolone in active crohn’s disease. the global budesonide study groupGut19974122092149301500

- CandySWrightJGerberMA controlled double blind study of azathioprine in the management of crohn’s diseaseGut19953756746788549944

- MarkowitzJGrancherKKohnNA multicenter trial of 6-mercaptopurine and prednisone in children with newly diagnosed crohn’s diseaseGastroenterology2000119489590211040176

- FeaganBGRochonJFedorakRNMethotrexate for the treatment of crohn’s disease. the north american crohn’s study group investigatorsN Engl J Med199533252922977816064

- FeaganBGFedorakRNIrvineEJA comparison of methotrexate with placebo for the maintenance of remission in crohn’s disease. north american crohn’s study group investigatorsN Engl J Med2000342221627163210833208

- BellSJKammMAReview article: The clinical role of anti-TNFalpha antibody treatment in crohn’s diseaseAliment Pharmacol Ther200014550151410792111

- ReineckerHCSteffenMWitthoeftTEnhanced secretion of tumour necrosis factor-alpha, IL-6, and IL-1 beta by isolated lamina propria mononuclear cells from patients with ulcerative colitis and crohn’s diseaseClin Exp Immunol19939411741818403503

- NichollsSStephensSBraeggerCPCytokines in stools of children with inflammatory bowel disease or infective diarrhoeaJ Clin Pathol19934687577608408704

- CornillieFShealyDD’HaensGInfliximab induces potent anti-inflammatory and local immunomodulatory activity but no systemic immune suppression in patients with crohn’s diseaseAliment Pharmacol Ther200115446347311284774

- LugeringASchmidtMLugeringNInfliximab induces apoptosis in monocytes from patients with chronic active crohn’s disease by using a caspase-dependent pathwayGastroenterology200112151145115711677207

- ten HoveTvan MontfransCPeppelenboschMPInfliximab treatment induces apoptosis of lamina propria T lymphocytes in crohn’s diseaseGut200250220621111788561

- ScallonBJMooreMATrinhHChimeric anti-TNF-alpha monoclonal antibody cA2 binds recombinant transmembrane TNF-alpha and activates immune effector functionsCytokine1995732512597640345

- HanauerSBFeaganBGLichtensteinGRMaintenance infliximab for Crohn’s disease: the ACCENT I randomized trialLancet20023591541154912047962

- ThayuMMarkowitzJEMamulaPHepatosplenic T-cell lymphoma in an adolescent patient after immunomodulator and biologic therapy for crohn diseaseJ Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr200540222022215699701

- ColombelJFSandbornWJRutgeertsPAdalimumab for maintenance of clinical response and remission in patients with Crohn’s disease: the CHARM studyGastroenterology2007132525517241859

- RutgeertsPD’HaensGTarganSEfficacy and safety of retreatment with anti-tumor necrosis factor antibody to maintain remission in Crohn’s diseaseGastroenterology199911776176910500056

- KugathasanSWerlinSLMartinezAProlonged duration of response to infliximab in early but not late pediatric crohn’s diseaseAm J Gastroenterol200095113189319411095340

- LionettiPBronziniFSalvestriniCResponse to infliximab is related to disease duration in paediatric crohn’s diseaseAliment Pharmacol Ther200318442543112940928

- BorrelliOBasciettoCViolaFInfliximab heals intestinal inflammatory lesions and restores growth in children with crohn’s diseaseDig Liver Dis200436534234715191204

- VeresGBaldassanoRNMamulaPInfliximab therapy in children and adolescents with inflammatory bowel diseaseDrugs200767121703172317683171

- de RidderLBenningaMATaminiauJAInfliximab use in children and adolescents with inflammatory bowel diseaseJ Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr200745131417592358

- BaldassanoRBraeggerCPEscherJCInfliximab (REMICADE) therapy in the treatment of pediatric crohn’s diseaseAm J Gastroenterol200398483383812738464

- CezardJPNouailiNTalbotecCA prospective study of the efficacy and tolerance of a chimeric antibody to tumor necrosis factors (remicade) in severe pediatric crohn diseaseJ Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr200336563263612717087

- HyamsJSMarkowitzJWyllieRUse of infliximab in the treatment of crohn’s disease in children and adolescentsJ Pediatr2000137219219610931411

- LamireauTCezardJPDabadieAEfficacy and tolerance of infliximab in children and adolescents with crohn’s diseaseInflamm Bowel Dis200410674575015626892

- HyamsJCrandallWKugathasanSInduction and maintenance infliximab therapy for the treatment of moderate-to-severe Crohn’s disease in childrenGastroenterology2007132386387317324398

- CrandallWHyamsJKugathasanSInfliximab therapy in children with concurrent perianal Crohn disease: observation from REACHJ Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr20094918319019561542

- RuemmeleFMLachauxACezardJPEfficacy of infliximab in pediatric Crohn’s disease: a randomized multi-center open-label trial comparing schedule to on demand maintenance therapyInflamm Bowel Dis20091538839419023899

- HyamsJSLererTGriffithsALong-term outcome of maintenance infliximab therapy in children with Crohn’s diseaseInflamm Bowel Dis20091581682219107783

- CandonSMoscaARuemmeleFClinical and biological consequences of immunization to infliximab in pediatric crohn’s diseaseClin Immunol20061181111916125467

- MieleEMarkowitzJEMamulaPHuman antichimeric antibody in children and young adults with inflammatory bowel disease receiving infliximabJ Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr200438550250815097438

- BaertFNomanMVermeireSInfluence of immunogenicity on the long-term efficacy of infliximab in crohn’s diseaseN Engl J Med2003348760160812584368

- FriesenCACalabroCChristensonKSafety of infliximab treatment in pediatric patients with inflammatory bowel diseaseJ Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr200439326526915319627

- CrandallWVMacknerLMInfusion reactions to infliximab in children and adolescents: Frequency, outcome and a predictive modelAliment Pharmacol Ther2003171758412492735

- JacobsteinDAMarkowitzJEKirschnerBSPremedication and infusion reactions with infliximab: Results from a pediatric inflammatory bowel disease consortiumInflamm Bowel Dis200511544244615867583

- VermeireSNomanMVan AsscheGAutoimmunity associated with anti-tumor necrosis factor alpha treatment in crohn‘s disease: A prospective cohort studyGastroenterology20031251323912851868

- MyersAClarkJFosterHTuberculosis and treatment with infliximabN Engl J Med2002346862362611859881

- KeaneJGershonSWiseRPTuberculosis associated with infliximab, a tumor necrosis factor alpha-neutralizing agentN Engl J Med2001345151098110411596589

- VeresGBaldassanoRNMamulaPInfliximab therapy in children and adolescents with inflammatory bowel diseaseDrugs200767121703172317683171

- ColombelJFLoftusEVJrTremaineWJThe safety profile of infliximab in patients with crohn’s disease: The mayo clinic experience in 500 patientsGastroenterology20041261193114699483

- KamathBMMamulaPBaldassanoRNListeria meningitis after treatment with infliximabJ Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr200234441041211930099

- EsteveMSaroCGonzalez-HuixFChronic hepatitis B reactivation following infliximab therapy in crohn’s disease patients: Need for primary prophylaxisGut20045391363136515306601

- CezardJPNouailiNTalbotecCA prospective study of the efficacy and tolerance of a chimeric antibody to tumor necrosis factors (remicade) in severe pediatric crohn diseaseJ Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr200336563263612717087

- LichtensteinGRFeaganBGCohenRDSerious infections and mortality in association with therapies for crohn‘s disease: TREAT registryClin Gastroenterol Hepatol20064562163016678077

- BianconeLOrlandoAKohnAInfliximab and newly diagnosed neoplasia in crohn’s disease: A multicentre matched pair studyGut200655222823316120759

- MackeyACGreenLLiangLCHepatosplenic T cell lymphoma associated with infliximab use in young patients treated for inflammatory bowel diseaseJ Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr200744226526717255842